Chapter 15

Growing Up, Growing Bigger, and Growing Old

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Understanding the life cycle of a product or service

Understanding the life cycle of a product or service

![]() Discovering ways to expand your business

Discovering ways to expand your business

![]() Juggling your product portfolio

Juggling your product portfolio

![]() Pondering two final questions about growth

Pondering two final questions about growth

Watching over a product or service as it makes its way through the cold, cruel marketplace is an awesome responsibility. It requires a major commitment of time and resources, as well as a great deal of careful planning. First, you have to understand what you must do to make the product a success. Which attributes and aspects should you stress? How do you make sure that people take notice (and like what they see)? How can you support and guide your product or service along the way, getting it into the right hands? You need to take advantage of opportunities as they appear. At the same time, you have to worry about the lurking threats and competitive pressures.

Does this sound a lot like rearing a child? Well, your product is your baby, and as any parent knows, you have to face one challenge after another as that little bundle of joy demands more and more. Think about how many times you’ve heard a parent say to those with a newborn, “You think they’re difficult now? Just wait!”

Products and kids have a great deal in common — both of their worlds continually change, yet they eventually manage to grow up. A key difference for new businesses is that you must ruthlessly be willing to reinvent and reshape your product or service to respond to your markets and industry (something you may want to avoid as a parent). Most new business ventures fail, and those that do break through barriers of resistance often do so via a quick pivot to a new path, learning from mistakes. Experience is usually not tuition free. For decades, the Dr. Spocks of the business world have poked, probed, pinched, and prodded products at all ages, and they’ve come up with a useful description of the common stages that almost all products go through. When you create a business plan, you have to plan for the changes in your product’s life cycle.

In this chapter, we explain the product life cycle and what it means for your company. We talk about ways to keep your company growing. We show you how to expand into new markets with existing products, as well as how to extend your product line to better serve current customers. We explore the opportunities and pitfalls of trying to diversify. We talk about strategic business units (SBUs) and introduce several “portfolio” tools to help you plan and manage a growing family of products. And we also remind you that bigger is not always necessarily better in the world of business.

Facing Up to the Product Life Cycle

In business, the only constant is — you guessed it — change. The forces of change are everywhere, ranging from major trends in your business environment to the shifting tastes and demands of your customers and the unpredictable behavior of your competitors. (For more info on change and how to prepare for it, visit Chapter 13.)

You may think that all these factors, stirred together, create a world filled with chaos and uncertainty. We can’t deny that, especially of late when change can be seen everywhere. But when it comes to growth, markets typically follow orderly and even predictable patterns. Experts have plotted some of these basic patterns, and the cycles that they’ve come up with aptly describe what happens in the face of all the market turmoil and confusion.

- An introduction period

- A growth period

- A period of market maturity and relative stability

- A period of decline

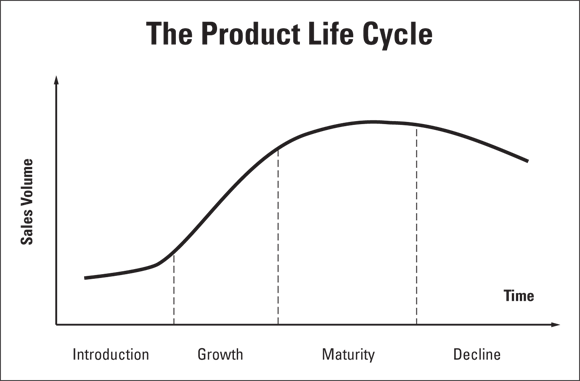

The product life cycle is closely related to how eager people are to try out a new product or service. (For a refresher on customer personality types and the diffusion of innovation in the marketplace, head to Chapter 6.) Most product life cycles look something like Figure 15-1.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 15-1: The product life cycle represents what’s likely to happen to sales volume for a typical product over time.

The curve traces your product sales volume over time. You can think about sales volume in terms of the revenue you take in or the number of units you sell. You may end up measuring the time scale in weeks, months, years, or even decades.

Every stage of your product’s life cycle presents a unique set of market conditions and a series of planning challenges. The different stages require different management objectives, strategies, and skills. The following sections discuss what you should think about at each stage.

Starting out

After you introduce a new kind of product or service in the market, it begins to generate revenue — at least you hope so. Because developing and launching something new is expensive, costs are relatively high at this stage, and you normally don’t find many competitors around. Growth depends on your company’s ability to make the product or service, generate market awareness, and get customers to accept and adopt it.

TABLE 15-1 Major Characteristics of the Introduction Stage

Component | Characteristics |

|---|---|

Industry | One or two companies, maybe you’re the first |

Competition | Little or none |

Key function | Research and development, creativity |

Customers | Innovators and risk-takers, unique groups |

Finances | High prices (usually) and expenses (most always) |

Profits | Nonexistent to negative |

Objectives | Product adoption |

Strategy | Establishing a toehold, expanding the market, survival |

Growing up

During the growth stage, the new product or service gains a reputation. If the product or service involves a new technology, the industry leaders agree upon standards — all the details that determine how the technology should work (see Chapter 14 for additional info). Demand rises rapidly, and sales increase. Competition increases as competing products jump into the fray to take advantage of an expanding market; “me-too” copycats multiply. Customers begin to develop brand loyalties, and companies tweak their product features to better serve customer needs — needs you can now recognize.

Maturing in middle age

The growth of your product or service begins to slow in the maturity stage as market demand levels off and new customers become harder to find. New competitors are also harder to find, so the competition stabilizes as the weak die off or get acquired. Profits keep on growing, however, as your costs continue to fall. Changes in market share reflect changes in the value that customers place on the competing products, and an increase in market share for one product usually comes at the expense of its competitors since overall demand has stabilized.

TABLE 15-2 Major Characteristics of the Growth Stage

Component | Characteristics |

|---|---|

Industry | Many companies |

Competition | Growing strength and numbers |

Key function | Marketing, demand management |

Customers | Eager to try likely successful products |

Finances | Variable prices and costs |

Profits | Finally on the horizon, maybe buckets full |

Objectives | Sales growth and market share |

Strategy | Establishing and defending position, professional management |

TABLE 15-3 Major Characteristics of the Maturity Stage

Component | Characteristics |

|---|---|

Industry | Not as many companies |

Competition | Stronger, but stable |

Key function | Operations, making them more efficient |

Customers | The majority of buyers know what they want |

Finances | Competitive prices and lower costs |

Profits | At or near peak |

Objectives | High cash flow and profit |

Strategy | Maintaining competitive position |

Riding out the senior stretch

Nothing lasts forever. Amen to that. At some point in a product’s life cycle, sales usually start to fall off and revenue begins to decline as market saturation occurs. Competitors drop out of the market as profits erode. Large-scale changes in the economy or in technology may trigger the decline stage, reflecting changing customer needs and behavior as alternatives emerge. Products and services still on the market at this stage are redesigned, repositioned, or replaced.

TABLE 15-4 Major Characteristics of the Decline Stage

Component | Characteristics |

|---|---|

Industry | Fewer companies |

Competition | Weakening |

Key function | Finance and planning for the future |

Customers | Loyal, conservative buyers — usually older |

Finances | Falling prices and low costs |

Profits | Much reduced; fire sales to clear old inventory |

Objectives | Residual profits, cash out what you can |

Strategy | Getting out alive |

Gauging where you are now

Take your product or service and see whether you can figure out its estimated position on the product life cycle curve (refer to Figure 15-1). If you’re stumped, ask yourself the following questions:

- How long has the product been on the market?

- How rapidly is the market growing (compared to prior years)?

- Is the growth rate increasing, decreasing, or flat?

- Is the product or service profitable?

- Are profits heading up or down?

- How fast are product features changing?

- How many competitors does your product have?

- Are there more or fewer competing products now compared to a year ago?

Finding Ways to Expand

Face it — your product simply isn’t going to be the same tomorrow as it is today. In Chapter 6, we tell the tale of good old Henry Ford and his famed market-leading Model T, available in any color you wanted — as long as it was black. But then other automakers began to offer choices, and we know what happened after that. You may not plan to change it at all, but everything around your product is going to change. The world will take another step ahead. The economy, technology, your industry, and the competition will all change. As a result, your current and future customers may think about your company and your product a bit differently, even if you don’t.

How can you find ways to grow and prosper as a company in the face of almost-certain product mortality? You probably have every intention of creating a new business plan as your product begins to age (just like the faith you had in actually carrying out all those New Year’s resolutions). But which way do you turn?

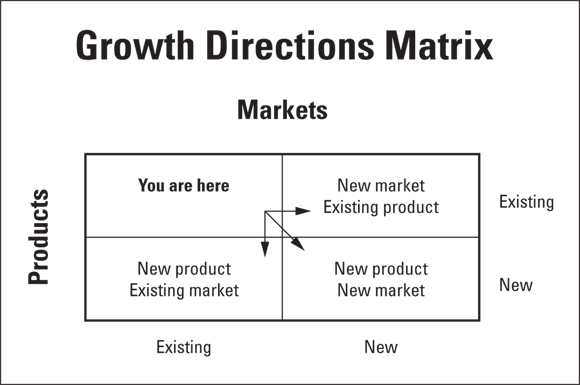

Fortunately, you don’t have to invent the alternatives yourself; planning for long-term growth has been a philosophical favorite of management gurus for decades. One of the pioneers of business-growth techniques was a brilliant immigrant to the United States from Russia named Igor Ansoff. He came up with a simple matrix to represent the possible directions of growth (see Figure 15-2).

- You are here (existing product and market): Continue to grow by doing what you do now, but do it a little bit better. Find ways to keep your users glued to your website for longer periods of time by adding new features, or package your product in new and different sizes to encourage usage at different times or on different occasions.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 15-2: The Ansoff Matrix describes different ways in which your company can grow, based on a combination of products and markets.

- New market, existing product: Grow in the short term by finding a fresh market for your existing product, either by expanding geographically or by reaching out to completely different kinds of customers. Home Depot opened stores in Latin America; Facebook tried to make its Instagram site more attuned to teens and tweens.

- New product, existing market: Grow by developing additional product features, options, or even a related product family with the intention of enticing your existing customers. McDonald’s starting offering breakfast menu items almost 20 years after being a strictly hamburger and fries provider. Business schools introduced “executive” MBA programs that offered prospective students a wider choice of attendance options such as weekends.

- New market, new product: Grow over the long term by going after new and unfamiliar markets with new and different products. Coca-Cola bought Columbia Pictures, a movie-making studio, and Harley-Davidson tried to sell branded bottled water.

Identify three things you can do right away to stimulate demand for your existing product in your current markets.

Offer rebates, start a sales promotion, or maybe come up with some new product uses or features.

List three steps you can take in the next six months to capture new markets for your existing product.

Create online ads that target new customers, start direct-mail campaigns, or step up appearances at trade shows. Find ecosystem partners and share resources.

Describe three directions you can take over the next three to five years that could move new products into new markets.

Engage in brainstorming sessions with colleagues to come up with growth opportunities, say exporting, that play into current company strengths. Or consider acquiring a company that competes in markets about which you currently have little prior experience.

Same product and same market

Many big-name companies have grown and achieved success by relentlessly managing a single business, a single market, or even one individual product decade after decade. When you see a Coca-Cola sign, for example, you imagine drinking a Coke. When you pass a McDonald’s, you probably picture a Big Mac. Your IT staff likely knows what Oracle and Cisco do, and the marketing folks are familiar with Salesforce.com. But these companies haven’t turned into billion-dollar corporations simply by launching their flagship product and letting the marketplace take care of the rest. Companies that largely depend on a single product spend enormous amounts of time and effort to continually rejuvenate and revitalize their core markets.

- Encourage greater product use. You can increase demand by encouraging your customers to consume more of a product or service every time they use it. Maybe that means getting customers to feel good about buying more or giving them a better deal when they do. Customers may do the following things:

- Buy larger boxes of cereal because they can save money

- Visit stores more often when they stay open longer or on weekends

- Buy more than one product and get a discount

- Generate more-frequent product use. You can stimulate sales by getting customers to use your product or service more often. That may mean making the product more convenient, introducing it as part of a customer’s regular routine, or offering incentives to frequent customers. Customers may do the following things:

- Use toothpaste after every meal because of the hygienic value

- Regularly drink wine at dinner because they’ve heard of its health benefits

- Join a frequent-flyer program and take an extra trip just to build more miles

- Devise new uses. You can expand your market by coming up with new ways for customers to use your product or service. That may include getting customers to use the product at different times, in different places, on novel occasions, or in unconventional ways. Customers may do the following things:

- Snack on breakfast cereal throughout the day because you make it handy and tasty

- Rent a spare bedroom that sits empty most of the time

- Desire a consumer version of an industrial usage product

- Woo customers away from competitors. You can increase demand for your product or service the old-fashioned way: Take customers away from the competition. Although the result is sometimes a fierce and unwanted response from competitors, you can do the following things:

- Create incentives for customers to switch from competing products and give them rewards for staying with you

- Concentrate on becoming the most attractive low-cost provider around because of your unbeatable prices

- Focus on meeting or exceeding the needs of specific customer segments or groups

New market or new product

At some point during the life of your company, a single product or service may not be enough to sustain an attractive level of growth. Where do you turn? The Ansoff Matrix (see Figure 15-2) suggests that the most reliable paths point to market expansion in the near term, as well as to extending your product line. These two directions for growth have the distinct advantage of building on capabilities and resources that you already have. You know what you’re doing and how to be efficient in doing it, so you offer it to new markets. Product extension builds on your experience and knowledge of your current customers: They know you and trust you and will likely give you a try when you have something new for them.

New market

Expanding into a new market is something you can do rather quickly by taking advantage of your current business model and copying many of your current business activities — producing, assembling, and distributing products, for example. Another way is to see what other goods or services consumers of your offerings purchase simultaneously. In many cases customers like the convenience of a one-stop shop.

Going after new markets involves risk, however. New markets force you to conduct business on a larger scale. New markets mean wooing new customers and dealing with new competitors. When you enter a new market, you’re the new kid on the block again, and you have to prove yourself at every step.

- Geography: The most obvious way to grow beyond your core product and market is to expand geographically, picking up new customers based solely on where they live and work. This kind of expansion has many advantages. You not only do business in the same way as before, but you also have a head start in understanding many of your new customers, even with their regional differences. Because geographic expansion may require you to do business in unfamiliar areas or even in new countries, however, you have to pay special attention to how your company must change to accommodate the specific demands of your expanded market. Better learn about those meters and kilos, as well as pesos or pounds.

- New market segments: Sometimes you can expand the market for your product or service by finding new kinds of customers. If you’re creative, you can identify a group of customers that you neglected in the past. Look carefully at your product’s features and packaging, how you price and deliver it, who buys it, and why they buy. Also, reassess the customer benefits that you provide. Ask yourself how attractive a new market segment is in terms of its size and potential to grow. What strengths do you bring to the market? What competitors are already there? (Check out Chapter 6 for more on market segments.)

New product

Extending the number of products or types of services that you offer is something that you should plan for well ahead of time. All too often, companies develop new product features, options, and major enhancements without giving much thought to the implications for the company’s future direction and growth. Instead, a customer asks for this or that special feature, or a distributor requests a particular option or accessory, and before you know it, you have additional products to support.

The good news, of course, is that you already have customers. But you also have to be sure that your customers represent a larger market that benefits from your product extension and that the additional products make sense in terms of your business strategy and plan.

New features and options: The most common way to extend a product line involves adding bells and whistles to your product and giving customers the chance to choose which bells and whistles they want. The advantages are easy to tick off: You work from your existing strengths in product design and development, and you use your customers to help you decide which incremental changes to make. It sounds like the perfect game plan.

The danger comes from losing track of the bigger picture — where you want your company to end up. Individual customers, no matter how good and loyal they are, don’t always reflect the direction of larger markets. So avoid creating a bunch of marginal products that you can’t successfully sell or support. Instead, plan to develop a smaller number of products with features and options that you design to meet the needs of specific market segments.

Related product groups: You may create a group of products based on a common element of some sort. You can develop a product family to use the same core technology, to meet a series of related customer needs, or to serve as accessories for your primary product.

You want the product group to look stronger in the market than the individual products do separately. That way, you reduce the risks inherent in product development, and the rewards are potentially greater. Take time to understand just how products in the group actually work together. Also, make sure you address the separate challenges that each product poses in terms of customers, the competition, your company mission and vision (refer to Chapters 3 and 4, respectively), and your company’s assets and capabilities.

Before you put your plans for growth into action, make sure that they draw on your company’s strengths, reflect the capabilities and resources that you have available, and help maintain your competitive advantage. Think about the following questions:

- How well are you doing in the markets that you currently occupy?

- In what ways is the expanded market different from your current market?

- What parts of your business can you leverage in the expanded market?

- What functions and activities have to change to accommodate more products?

- How well does your extended product line meet specific customer needs?

- Is your extended product family stronger than each product by itself?

- How easy is it to scale up your business to meet the expected growth?

- How will your competitive environment change?

New product and new market

Has your company hit a midlife crisis? Do you find yourself searching for attractive new customers and hot new technologies, feeling the pinch of age? The need for rejuvenation comes to many companies at different times. A plan to move in new directions often involves diversifying the company, a move down into the bottom-right corner of the Ansoff Matrix (refer to Figure 15-2). That corner, after all, is where the grass — and the profits — always looks much greener.

To improve your odds of success, start by doing your homework, which means researching all the new issues and new players. If this task sounds daunting, it should be. The stakes couldn’t be much higher.

- Name recognition: If you work hard to create a name for your company, you can sometimes make use of your brand identity in a new business situation. Name recognition is particularly powerful when the name has positive, clearly defined associations that you can carry over to the new product and market. Luxury-car companies such as BMW, for example, now give their names to expensive, upscale lines of touring and mountain bicycles. Many celebrities generate money through product endorsements.

- Technical operations: The resources and skills required to design, develop, or manufacture products in your industry — or perhaps the technical services that you offer — may be extended to bring in additional streams of revenue. Amazon realized its expertise in designing and operating a huge online sales and distribution platform could be a service others would be willing to pay for.

- Capacity and scale: Sometimes you can take the excess capacity that you or your company has in production, sales, or distribution and apply that capacity directly to a new business area. You reap the benefits of a larger scale of operations and use your resources more efficiently. Uber, Lyft, and Turo are on-demand ride-sharing services that give car owners a source of additional income.

- Financial considerations: Persistent demands on your company’s revenue, cash flow, or profits may inevitably point you in a new direction. Low-margin businesses might be exited and new ventures entered that offer higher returns. Weetabix, a UK-based breakfast cereal maker with U.S. and Canadian markets, dumped about 14 percent of its private-label business and discontinued its Barbara’s cereal bars line. The result was a double-digit increase in profits and funds to try out some new ideas.

Surprise, surprise — all of these new venture ideas failed, most immediately upon launch. What were they thinking? Strong brands, insider contacts, surplus resources — too many firms thought that these alone would lead to success in new markets. Business planning is a serious business, and it needs to be taken seriously.

A few companies, however, manage to succeed with new products and new markets time and time again. What the Wall Street types call “unrelated diversification” and the business school texts call conglomerates work for some, if managed with precision and discipline (and perhaps a little luck as well).

Newell Corporation, now called Newell Brands in recognition that its product portfolio is all over the map, is an example. Food-related brands include Ball and Calphalon; commercial products, in addition to Rubbermaid, include Quickie and MAPA; Mr. Coffee and Oster are in the home appliances unit; Dymo, Paper Mate, and Parker are in writing; baby brands include Graco and Aprica; Coleman and Marmot are in outdoor and recreation; Wood Wick and Yankee Candle are at home in home fragrance; and finally First Alert is in the connected home and security group. Whew — in fact double whew, since there are more brands than just these at Newell Brands.

The glue that binds all these disparate businesses together under one roof is called “synergy.” That’s more B-School blah-blah, like conglomerate. (Both terms derive from geology. The good professors probably thought that if they coined words from real science, then people would start to believe they were in fact real scientists. Hah! Fat chance of that.) The underlying concept of synergy was that astute planners could find unique means to generate additional value from two or more entities. This is the old “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts” logic, more conveniently demonstrated as 2 + 2 = 5. How so? Perhaps two of Newell Brands’ business units purchase similar raw materials, even though they are used in very different ways at each. But by combining both units’ orders into one, Newell could command a lower price from the supplier through a volume discount. Also, bringing all of the personnel of all of the units together in one firm gives Newell an enlarged pool of talent to draw from as it promotes individuals and moves them around to share their expertise and wisdom.

Newell is a shining example of the tiny universe of firms successfully managing an unrelated diversification strategy. For generations the gold standard in this class was the General Electric Corporation (see the later section “Utilizing strategic business units”). Others, like Berkshire Hathaway, run by the investment superstar Warren Buffett, were more like “holding companies.” These firms were composed of numerous individual units who were acquired and left to operate on their own by the parent corporation, remitting profits to the parent that “held” them. There was little if any attempt to integrate operations of the many into a single standard approach. The benefit of this approach at diversification was primarily spreading risk. Another was that the parent could act as a kind of central bank for all the subsidiary businesses, sourcing funds at more favorable rates than if done individually.

Managing Your Product Portfolio

When you decide that you want to branch out with new products and into new markets or to diversify into new businesses, you have to figure out how to juggle. What do we mean? You no longer have the luxury of doting on a single product or service. With more than one product and market to deal with, you have to figure out how to keep each of them aloft, providing each with the special attention and resources that it needs, depending on where it stands on the product life cycle (see Figure 15-1). You need the kind of organization and management provided by strategic business units, known as SBUs.

Utilizing strategic business units

- How many products or services does your company have?

- When you add another feature or an option to your product, will the addition essentially create a new product that requires a separate business plan?

- When you have two separate sets of customers that use your service in different ways, do you really have two services, each with its own business plan?

- When you offer two different products, each of which you manufacture, market, and distribute in much the same way, to the same set of customers, are you really dealing with one larger product area and a single business plan?

Often, these questions have no right answer, but taking time to think through the issues helps you better understand what you offer. The firm that pioneered how to do this task best was the General Electric Corporation, or at least it used to be.

General Electric struggled with questions about how to manage its many businesses in the late 1960s. The company had grown well beyond the original inventions of its famed founder, Thomas Edison; it wasn’t just in the electric light bulb business any more. In fact, it was a diversified giant, with businesses ranging from appliances and aircraft engines to television sets and computers to finance and plastic. GE had to figure out the best way to divide itself up so that each piece was a manageable size that the company could successfully juggle along with all the other pieces — and be more than a mere holding company.

The managers at General Electric hit on the clever idea of organizing the company around what they called strategic business units. An SBU is a piece of your company that’s big enough to have its own well-defined markets, attract its own set of competitors, and demand common resources and capabilities from you. Yet an SBU is small enough that you can craft a strategy for it, with goals and objectives designed to reflect its special business environment. By using the SBU concept, General Electric transformed nearly 200 independent product or service divisions into fewer than 50 strategic business units, each with its own well-defined strategy and business plan that could be managed efficiently.

- Break your company into as many separate product and market combinations as you can think of.

Fit these building blocks back together in various ways, trying all sorts of creative associations of products and markets on different levels and scales.

Think about how each combination may work in terms of creating a viable business unit.

- Keep only the combinations of products and markets that make sense in terms of strategy, business planning, customers, the competition, and your company’s structure.

Determine how well these new SBUs mesh together and account for your overall business.

If you don’t like what you see, try the process again. Don’t change the way you define your products and markets with SBUs — or the way you organize your business and allocate resources around them — until you’re satisfied with the overall structure of the company.

Aiming for the stars

Managing a number of products or services is similar to managing a set of financial investments. Take your personal savings or retirement accounts, for example (boy, now there’s an assumption). Every financial counselor tells you the same thing: You should spread out your investments to create a more stable and predictable set of holdings. Ideally, financial counselors want to help you balance your financial portfolio based on how much money you need to earn right away and what sort of nest egg you expect to have in the future. Given your financial needs and goals, planners may suggest that you buy blue-chip stocks and bonds that generate dividends right away and that you also invest in more speculative tech companies that might pay off well down the road.

Your company’s products and services have a great deal in common with a portfolio of stocks and bonds — so much, in fact, that the juggling of your products and services is called portfolio management. To manage your product portfolio as professionally as financial experts track stocks and bonds, you need some guidance. Portfolio analysis helps you look at the different roles of the products or services in your company and determine how well they balance one another so that the company grows and remains profitable. In addition, portfolio analysis offers a new way to think about strategy and business planning when you have more than one product or service to worry about.

To juggle your collection of products or services (or SBUs, if you divide them up as we suggest in the previous section), start by dividing them into two basic groups, depending on the direction of their cash flow: Put the ones that bring money into your company on one side and the ones that take money out on the other side.

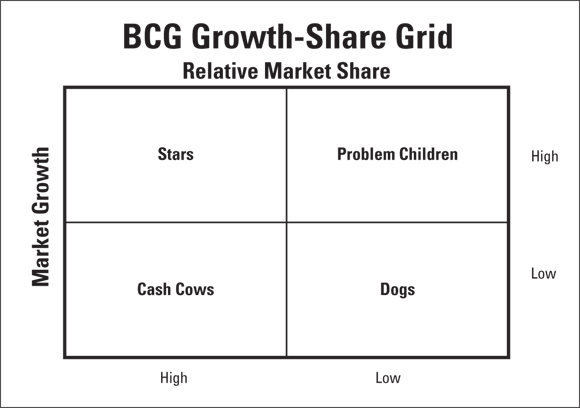

Understanding the Growth-Share Grid

You could make a first attempt at portfolio analysis now, using the two basic product groups: those that make money and those that take money. All you have to do is make sure that the first category is always bigger than the second. But the two categories don’t help you figure out the future. Fortunately, the bright guys and gals at the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) came up with an easy-to-use portfolio-analysis tool that provides some useful planning direction. The BCG’s Growth-Share Grid (see Figure 15-3) directs you to divide your products or services into four groups.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 15-3: The Growth-Share Grid divides your company’s products or services into four major groups.

- Market growth: Is the product or service part of a rapidly expanding market, or does it fall somewhere in a slow- or no-growth area? You use market growth to define your portfolio because it forces you to think about how attractive the product or service may be over the long haul. The exact point that separates high-growth and low-growth markets is rather arbitrary; start by using a 10 percent annual growth rate as the midpoint, but adjust this according to what’s happening in your own industry.

- Relative market share: Does your product command a market-share advantage over its nearest competitors, or does its market share place it down on the list relative to the competition? You use relative market share as a major characteristic to define your product portfolio because evidence suggests that a strong market-share position is closely tied to the profitability of a product. Separate your products into those that command the highest market share and those that don’t.

- Problem children: These products have relatively low market share in high-growth markets. Problem children often represent newer businesses and are sometimes referred to as question marks because you aren’t quite sure which path these products may take in the future. Because problem children are in expanding markets, they require plenty of cash just to tread water and maintain what market share they already have, but their relatively low sales generate little or no revenue in return. If you can substantially increase their market share over time — and that means shelling out even more cash — problem children can blossom into stars. If not, you may have to give up these products and just let them drown.

- Stars: These products have a dominant market-share position in high-growth markets. Every product wants to be a star. Stars usually have an expensive appetite for the cash needed to fund continual expansion and to fend off competitors that want to get a piece of the action. But their market-share advantage also gives these products an edge in generating revenue, margins, and profits. So stars usually support themselves, both producing and consuming large amounts of money. You shouldn’t hesitate to step in and support a star product, however, if it requires additional resources to maintain its market-share lead.

- Cash cows: These products have a major market-share position in low-growth markets. Because of their market-share advantage, cash cows generate a great deal of cash without requiring much in return. Their low-growth markets are mature, and the products are already well-established. The bottom line: You can milk cash cows to produce a cash surplus and then redirect that cash to fund promising products in other quadrants of the grid.

- Dogs: These products deliver low market share in low-growth markets — and little else. Although many people are dog lovers, this particular junkyard breed is hard to love. Revenue and profits usually are small or nonexistent, and the products are often net users of cash. Although they require periodic investments, these marginal business ventures usually never amount to much, so it may be best to dump ’em at the pound, cut your losses, and turn your attention to more-promising product candidates.

Building your own Growth-Share Grid

Now you can put all the pieces together to construct a Growth-Share Grid that represents your portfolio of products and services. Ideally, of course, you want to see mostly stars and cash cows, with enough problem children (the risky question marks) to ensure your company’s future.

Sort through your company’s products or services and get ready to put them in a blank Growth-Share Grid.

To see the grid format, refer to Figure 15-3.

- Place each product in its proper quadrant, given what you know about market growth and the product’s relative market share.

Draw a circle around each product to represent how big it is in relation to your other products.

Base the size of your product circles on revenue, profits, sales, or whatever measure is most convenient. The size of the circles measures the relative importance of each product to your company today — big circles for plus size, small circles for the less so.

For each product in the grid, forecast its movement in terms of overall market growth and market-share position.

Use an appropriate time frame in regard to your industry and its rate of change — say one to three years out.

To capture this forecast, draw arrows indicating the direction of the movement and where you plan to have each product end up in the future.

Arrows that point outside the grid indicate that you plan to get rid of the products in question.

- Market growth is singled out as the only way to measure how attractive a market is and to determine whether you want to be in business there. But growth isn’t the only interesting variable. Markets may become attractive because of advances in technology, changes in regulation, and profits, to name a few.

- Relative market share describes how competitive you are and how profitable your company is likely to be. But market share is relevant only when you compete on the basis of size and sales volume. You can compete in other ways, including making your product unique in some way, focusing on a particular group of customers, or concentrating on service.

- The products you put on the Growth-Share Grid are linked only by the flow of cash in and out of the business. But you can think about how products and services may relate to one another and function together in other ways, including views that stress the competition or focus on market risk factors (for example, so-called “loss leader” products that attract customers to your other more profitable offerings).

- The differences between a star and a cash cow (or a problem child and a dog) are arbitrary and subject to many definition and measurement problems. Without careful analysis and a dose of good judgment, you may cast your products in the wrong roles. You may end up abandoning a problem child too soon, for example, because you think the product is a dog, or you may neglect and hurt a star product by labeling it as a cash cow that you can simply milk for money.

Asking Two Final Questions About Growth

The earlier references to GE allow us to conclude this chapter with both wisdom and warnings when you think about growth goals as part of your business-planning task. You and just about everyone else probably believe that growing your business is what it’s all about. If you have investors or shareholders, that’s usually why they’re there in the first place. We have no quarrel with this.

- Do you absolutely have to grow?

- Can you manage the outcome of growth — a huge enterprise — well?

Knowing that, yes, growth is good

The transformation of the economy in the 21st century has cast a new light on growth. In Chapter 5 we inform you of entry barriers in business — that is, those means by which competitors try to keep out any potential new entrants. But today’s “new economy” has created a powerful new barrier. Ask yourself: Why do you use Microsoft for your word processing, Google for search, Facebook for social media, or perhaps Amazon for online shopping — all to the exclusion of any other platforms? Is it because we just love these rascals to death? No comment.

The herringbone tweed with leather patch and pipe folks have provided an answer by drawing attention to one barrier that’s become increasingly important — and controversial — for lots of new industries today, perhaps one that you’re considering entering yourself. Excuse the jargon but it’s called a “network externality effect.” (Yes, we know it’s academese, but that’s what we do.) Firms such as Microsoft and others learned that they’re competing in a winner-take-all game and being first is critical, for reasons both economic as well as psychological. From we customers’ point of view (POV in Millennial-speak), there is a huge benefit to having but a single network to meet our needs. How so?

Suppose that there were half a dozen equally sized platforms for creating and sharing online word processing documents. You conjure up a brilliant survey of the prospects for success in your new venture and want to send it out to trusted friends for comment. But uh-oh; some would-be recipients use your platform, others don’t. In fact, you realize you have to format the darn thing in six different versions, and even then you can’t shoot it to everyone because your PC is loaded with only MS Office. Microsoft became dominant because ol’ Bill realized that his industry would be captured by the one provider that quickly roped in the most users. Each new user to join the network would drive up its value. Being “best” wasn’t nearly as important as being first, because after you purchased his software, installed it on your PC, and learned how to use it, the switching costs to a superior alternative weren’t worth the effort. Any new buyers of the product would likely also go for MS Office because that’s what everyone else had.

And what might have been the true business brilliance of Mr. Gates was offering a low price for his operating system to PC manufacturers only on the condition that it be pre-installed on their machines. After IBM agreed, other competitors joined in. You went to your friendly electronics retailer, selected and paid for a new PC, and when you got home and fired it up, presto, there was MS-DOS up and ready to go. Genius! For Microsoft, this software became the gift that just keeps giving. (Perhaps a pithier substitute for network externality effect would be the QWERTY effect. Don’t know it? Google the term and you’ll see.)

So, is your market one that is of the winner-take-all platform variety where first-mover benefits are powerful? If so, you want to grow as fast as possible, signing up users before they migrate to an alternative platform. This logic was seen in the behavior of venture capitalists who funded such start-ups: Spend everything and more on marketing and don’t worry about profit. When you hit a certain threshold and you dominate your market, then bottom-line issues can be discussed. (Some, in fact, even paid users to join.) This doesn’t mean you ignore customer needs once they’re locked in, of course. This was the MySpace problem described earlier in this chapter. But by becoming the big dog in the show, everyone else has to come up with a very good reason to convince users to switch to them — and a lot of them would have to do so before that rival site becomes valuable.

Managing growth wisely

For much of the last half of the 20th century, there was near universal consensus that General Electric was the best-managed large firm in the United States. We note some of GE’s contributions to strategic management in this chapter. Under the dynamic leadership of the firm’s charismatic CEO Jack Welch, GE in 2000 became the world’s most valuable public firm; Fortune magazine dubbed him “manager of the century.” GE competed in 14 different large business segments and was a leader in all of them. This diversity, it was claimed, allowed the firm to overcome cyclical issues that affected firms that “stuck to their knitting.” The market capitalization of GE was more than $600 billion in 2000.

Through its innovative and effective management practices, the firm showed that the conventional wisdom regarding unrelated diversification strategies — that is, avoid them — didn’t seem to apply to it. Many informed observers, in fact, regarded its internal management training center as a Top 10 business school. GE managers were sought and poached by companies everywhere.

But nothing is forever, a theme we repeat often in this book. Mr. Welch’s last day as CEO was September 9, 2001. The new CEO, Mr. Jeff Immelt, took over just one day prior to the 9/11 tragedy. As the world irrevocably changed, many of the hidden problems with GE began to surface as new realities sank in and digital commerce began to flourish. These were compounded when, following the Great Recession of 2008, an overreliance on the firm’s finance subsidiary, GE Capital, led to huge losses and write-offs of assets. Many management experts now wrote that as a decentralized conglomerate, GE was “too big to manage.” Each business line and division operated autonomously with decentralized budgets and duplicate, triplicate, and often even more repetitive infrastructures; an aggressive culture of winning often pitted units against one another in the dog fight for promotion up the corporate ladder. Without strong centralized governance and management oversight, compounded by continuous investor pressure to improve its market value, GE’s performance floundered.

Mr. Immelt was removed as CEO in 2017. Assets and whole lines of business were sold off to pay down debt. GE’s revenue level and market capitalization dropped to the point that GE was removed from the list of firms that comprised the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the traditional metric used to measure stock market performance in the United States. GE had been the only firm that had been on the list since its inception more than 100 years prior.

One of these patterns — the product life cycle — illustrates what happens to a new kind of product or service after you launch it in the market. The cycle describes four major stages that a new product will likely traverse from birth to obsolescence:

One of these patterns — the product life cycle — illustrates what happens to a new kind of product or service after you launch it in the market. The cycle describes four major stages that a new product will likely traverse from birth to obsolescence:  Even if you feel confident about your product’s position in its life cycle, take the time to confirm your analysis. You’re likely to get mixed signals from the marketplace, and the clues you find may even contradict one another. No two products ever behave exactly the same way when it comes to product life cycle. Unfortunately, acting prematurely on the evidence at hand can lead to hasty planning and a self-fulfilling prophecy. The product life cycle concept, after all, is not a law of physics. So be sure you always double-check what you think you see to make sure you don’t mistake a temporary hiccup in sales for a full-scale life cycle change.

Even if you feel confident about your product’s position in its life cycle, take the time to confirm your analysis. You’re likely to get mixed signals from the marketplace, and the clues you find may even contradict one another. No two products ever behave exactly the same way when it comes to product life cycle. Unfortunately, acting prematurely on the evidence at hand can lead to hasty planning and a self-fulfilling prophecy. The product life cycle concept, after all, is not a law of physics. So be sure you always double-check what you think you see to make sure you don’t mistake a temporary hiccup in sales for a full-scale life cycle change. Without getting bogged down in a lot of details, try to come up with a dozen different ways to grow your company. Get yourself into the right frame of mind by reviewing your company’s mission and vision statements. (Don’t have ’em? Flip to

Without getting bogged down in a lot of details, try to come up with a dozen different ways to grow your company. Get yourself into the right frame of mind by reviewing your company’s mission and vision statements. (Don’t have ’em? Flip to