Chapter 9

Preventing Social Engineering Attacks

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Being aware of the various forms of social engineering attacks

Being aware of the various forms of social engineering attacks

![]() Discovering the strategies that criminals use to craft effective social engineering attacks

Discovering the strategies that criminals use to craft effective social engineering attacks

![]() Realizing how overshared information can help criminals

Realizing how overshared information can help criminals

![]() Protecting yourself and your loved ones from social engineering attacks

Protecting yourself and your loved ones from social engineering attacks

Most, if not all, major breaches that have occurred in recent years have involved some element of social engineering. Do not let devious criminals trick you or your loved ones. In this chapter, you find out how to protect yourself.

Don’t Trust Technology More than You Would People

Would you give your online banking password to a random stranger who asked for it after walking up to you in the street and telling you that they worked for your bank?

If the answer is no — which it certainly should be (and, if it is not, your security problems are much greater than just your cybersecurity) — you need to exercise the same lack of trust when it comes to technology. The fact that your computer shows you an email sent by some party that claims to be your bank instead of a random person approaching you on the street and making a similar claim is no reason to give that email your trust any more than you would give the stranger.

In short, you don’t give offers from strangers approaching you on the street the benefit of the doubt, so don’t do so for offers communicated electronically — they may be even more risky.

Types of Social Engineering Attacks

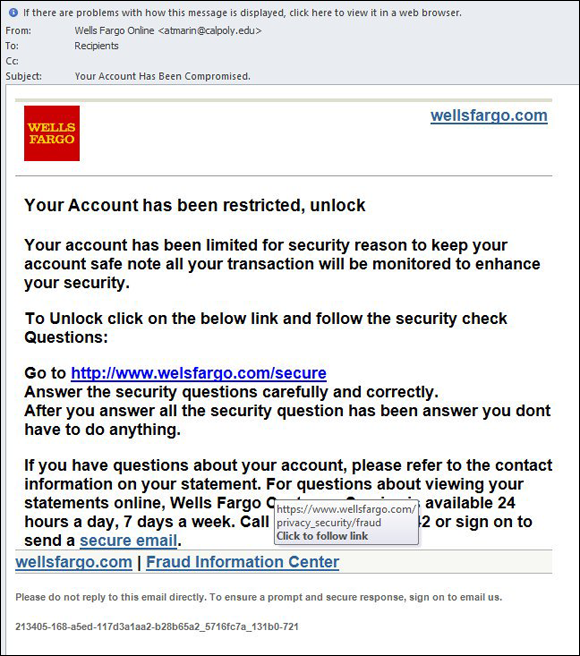

Phishing attacks are one of the most common forms of social engineering attacks. (For more on phishing and social engineering, see Chapter 2.) Figure 9-1 shows you an example of a phishing email.

FIGURE 9-1: A phishing email.

Phishing attacks sometimes utilize a technique called pretexting in which the criminal sending the phishing email fabricates a situation that both gains trust from targets as well as underscores the supposed need for the intended victims to act quickly. In the phishing email shown in Figure 9-1, note that the sender, impersonating Wells Fargo bank, included a link to the real Wells Fargo within the email, but failed to properly disguise the sending address.

Chapter 2 discusses common forms of social engineering attacks, including spear phishing emails, smishing, spear smishing, vishing, spear vishing, and CEO fraud. Additional types of social engineering attacks are popular as well:

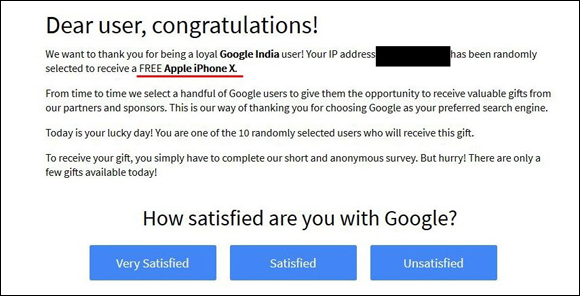

Baiting: An attacker sends an email or chat message — or even makes a social media post that promises someone a reward in exchange for taking some action — for example, telling intended targets that if they complete a survey, they will receive a free item (see Figure 9-2). Or that if they perform such action, they will receive some free cryptocurrency. Sometimes such promises are real, but often they’re not and are simply ways of incentivizing people to take a specific action that they would not take otherwise. Sometimes such scammers seek payment of a small shipping fee for the prize, sometimes they distribute malware, and sometimes they collect sensitive information. There is even malware that baits.

FIGURE 9-2: Example of a baiting message.

Don’t confuse baiting with scambaiting. The latter refers to a form of vigilantism in which people pretend to be gullible, would-be victims, and waste scammers’ time and resources through repeated interactions, as well as (sometimes) collect intelligence about the scammer that can be turned over to law enforcement or published on the Internet to warn others of the scammer. I have sometimes led scammers on when they call by listening to their spiel and then giving them the FBI’s New York office contact information for their requested follow-up call.

Don’t confuse baiting with scambaiting. The latter refers to a form of vigilantism in which people pretend to be gullible, would-be victims, and waste scammers’ time and resources through repeated interactions, as well as (sometimes) collect intelligence about the scammer that can be turned over to law enforcement or published on the Internet to warn others of the scammer. I have sometimes led scammers on when they call by listening to their spiel and then giving them the FBI’s New York office contact information for their requested follow-up call.- Quid pro quo: The attacker states that they need the person to take an action in order to render a service for the intended victim. For example, an attacker may pretend to be an IT support manager offering assistance to an employee in installing a new security software update. If the employee cooperates, the criminal walks the employee through the process of installing malware.

- Social media impersonation: Some attackers impersonate people on social media in order to establish social media connections with their victims. The parties being impersonated may be real people or nonexistent entities. The scammers behind the impersonation shown in Figure 9-3 and many other such accounts frequently contact the people who follow the accounts, pretending to be the account owners, and request that the followers make various “investments.”

FIGURE 9-3: An example of an Instagram account impersonating me, using my name, bio, and primarily photos lifted from my real Instagram account.

- Tantalizing emails: These emails attempt to trick people into running malware or clicking on poisoned links by exploiting their curiosity, sexual desires, and other characteristics.

- Tailgating: Tailgating is a physical form of social engineering attack in which attackers accompany authorized personnel as they approach a doorway that they, but not the attackers, are authorized to pass and tricks them into letting the attackers pass with the authorized personnel. The attackers may pretend to be searching through a purse for an access card, claim to have forgotten their card, or may simply act social and follow the authorized party in.

- False alarms: Raising false alarms can also social engineer people into allowing unauthorized people to do things that they should not be allowed to. Consider the case in which an attacker pulls the fire alarm inside a building and manages to enter normally secured areas through an emergency door that someone else used to quickly exit due to the so-called emergency.

- Water holing: Water holing combines hacking and social engineering by exploiting the fact that people trust certain parties, so, for example, they may click on links when viewing that party’s website even if they’d never click on links in an email or text message. Criminals may launch a watering hole attack by breaching the relevant site and inserting the poisoned links on it (or even depositing malware directly onto it).

Virus hoaxes: Criminals exploit the fact that people are concerned about cybersecurity, and likely pay undeserved attention to messages that they receive warning about a cyberdanger. Virus hoax emails may contain poisoned links, direct a user to download software, or instruct a user to contact IT support via some email address or web page. These attacks come in many flavors — some attacks distribute them as mass emails, while others send them in a highly targeted fashion.

Some people consider scareware that scares users into believing that they need to purchase some particular security software (as described in Chapter 2) to be a form of virus hoax. Others do not because scareware’s “scaring” is done by malware that is already installed, not by a hoax message that pretends that malware is already installed.

- Technical failures: Criminals can easily exploit humans’ annoyance with technology problems to undermine various security technologies. For example, research I performed nearly two decades ago showed that if a criminal impersonates a website that normally displays a security image in a particular area, but in the fake copy, places a “broken image symbol,” many users will not perceive danger, as they are accustomed to seeing broken-image symbols and associate them with technical failures rather than security risks. There is no reason to believe that over the years anything has changed for the significantly better in this regard.

Six Principles Social Engineers Exploit

Social psychologist Robert Beno Cialdini, in his 1984 work published by HarperCollins, Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, explains six important, basic concepts that people seeking to influence others often leverage. Social engineers seeking to trick people often exploit these same six principles, so I provide a quick overview of them in the context of information security.

- Social proof: People tend to do things that they see other respectable people doing.

- Reciprocity: People, in general, often believe that if someone did something nice for them, they owe it to that person to do something nice back.

- Authority: People tend to obey authority figures, even when they disagree with the authority figures, and even when they think what they are being asked to do is objectionable.

- Likeability: People are, generally speaking, more easily persuaded by people who they like than by others.

- Consistency and commitment: If people make a commitment to accomplish some goal and internalize that commitment, that commitment becomes part of their self-image. They are likely, therefore, to attempt to pursue their goal even if the original reason for pursuing the goal is no longer relevant.

- Scarcity: If people think that a particular resource is scarce, regardless of whether it actually is scarce, they will want it, and often take risks to obtain it, even if they don’t actually need it.

Don’t Overshare on Social Media

Oversharing information on social media arms criminals with material that they can use to social engineer you, your family members, your colleagues at work, and your friends. If, for example your privacy settings allow anyone with access to the social media platform to see your posted media, your risk increases. Many times, people accidentally share posts with the whole world that they actually intended to be visible and/or audible by only a small group of people.

Furthermore, in multiple situations, bugs in social media platform software have created vulnerabilities that allowed unauthorized parties to view media and posts that had privacy settings set to disallow such access.

Also, consider your privacy settings. Family-related material with privacy settings set to allow nonfamily members to view it may result in all sorts of privacy-related issues and leak the answers to various popular challenge questions used for authenticating users, such as “Where does your oldest sibling live?” or “What is your mother’s maiden name?” And consider that romantic relationships can sour, too; there may be materials from previous relationships that you do not want a new partner to see, or vice versa.

Your schedule and travel plans

Details of your schedule or someone else’s schedule may provide criminals with information that may help them set up an attack. For example, if you post that you’ll be attending an upcoming event, such as a wedding, you may provide criminals with the ability to virtually kidnap you or other attendees — never mind incentivizing others to target your home with a break-in attempt when the home is likely to be empty. (Virtual kidnapping refers to a criminal making a ransom demand in exchange for the same return of someone who the criminal claims to have kidnapped, but who in fact, the criminal has not kidnapped.)

Likewise, revealing that you’ll be flying on a particular flight may provide criminals with the ability to virtually kidnap you or attempt CEO-type fraud against your colleagues. They may impersonate you and send an email saying that you’re flying and may not be reachable by phone for confirmation of the instructions so just go ahead and follow them anyway.

Financial information

Sharing a credit card number may lead to fraudulent charges, while posting a bank account number can lead to fraudulent bank activity.

In addition, don’t reveal that you visited or interacted with a particular financial institution or the locations where you store your money — banks, crypto-exchange accounts, brokerages, and so forth. Doing so can increase the odds that criminals will attempt to social engineer their way into your accounts at the relevant financial institution(s). As such, such sharing may expose you to attempts to breach your accounts, as well as targeted phishing, vishing, and smishing attacks and all sorts of other social engineering scams.

Posting about potential investments, such as stocks, bonds, precious metals, or cryptocurrencies, can expose you to cyberattacks because criminals may assume that you have significant money to steal. In some cases, if you make posts encouraging people to investor to perform other forms of investment-related activities, you may also run afoul of rules laws or of regulations of the SEC, CFTC, or other government bodies. You may even also open the door to criminals who impersonate regulators and contact you to pay a fine for posting information inappropriately.

Personal information

For starters, avoid listing your family members in your Facebook profile’s About section. That About section links to their Facebook profiles and explains to viewers the nature of the relevant family relationship with each party listed. By listing these relationships, you may leak all sorts of information that may be valuable for criminals. Not only will you possibly reveal your mother’s maiden name (challenge question answer!), you may also provide clues about where you grew up. The information found in your profile also provides criminals with a list of people to social engineer or contact as part of a virtual kidnapping scam.

Also you should avoid sharing the following information on social media, as doing so can undermine your authentication questions and help criminals social engineer you or your family:

- Your father’s middle name

- Your mother’s birthday

- Where you met your significant other

- Your favorite vacation spot

- The name of the first school that you attended

- The street on which you grew up

- The type, make, model, and/or color of your first car or someone else’s

- Your or others’ favorite food or drink

Likewise, never share your Social Security number as doing so may lead to identity theft.

Information about your children

Timestamps and geotagging do not need to be done per some technical specification to create risks. If it is clear from the images where your kids go to school, attend after-school activities, and so on, you may expose them to danger.

In addition, referring to the names of schools, camps, day care facilities, or other youth programs that your children or their friends attend may increase the risk of a pedophile, kidnapper, or other malevolent party targeting them. Such a post may also expose you to potential burglars because they’ll know when you’re likely not to be home. The risk can be made much worse if a clear pattern regarding your schedule and/or your children’s schedule can be extrapolated from such posts. Also avoid posting about a child’s school or camp trip. And, if you feel you must post about it, wait until your child is back home after completing the trip.

Information about your pets

As with your mother’s maiden name, sharing your current pet’s name or your first pet’s name can set you or others who you know up for social engineering attacks because such information is often used as an answer to authentication questions.

Work information

Details about with which technologies you work with at your present job (or a previous job) may help criminals both scan for vulnerabilities in your employers’ systems and social engineer your colleagues. Yet many people’s profiles on profession-focused social media sites contain a wealth of information about the systems in use at their employers — sometimes even effectively disclosing the public what security systems the employer is using, and is considering for use in the future.

Possible cybersecurity issues

Many virus hoaxes and scams have gone viral — and inflicted far more damage than they should have — because criminals exploit people’s fear of cyberattacks and leverage the likelihood that many people will share posts about cyber-risks, often without verifying the authenticity of such posts.

Crimes and minor infractions

Information about a moving violation or parking ticket that you received not only presents yourself in a less-than-the-best light, but can inadvertently provide prosecutors with the material that they need to convict you of the relevant offense. You may also give crooks the ability to social engineer you or others — they may pretending to be law enforcement, a court, or an attorney contacting you about the matter — perhaps even demanding that a fine be paid immediately in order to avoid an arrest.

In addition to helping criminals social engineer you in a fashion similar to the moving violation case, information about a crime that you or a loved one committed may harm you professionally and personally.

Medical or legal advice

If you offer medical or legal advice, people may be able to extrapolate that you or a loved one has a particular medical condition, or involved in a particular legal situation. And, if you offer incorrect advice, you could not only get yourself into hot water and legal troubles, but also contribute to unnecessary human suffering.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, social media platforms were regularly used to spread incorrect information — and this spread might have contributed both to increasing the number of coronavirus illnesses and deaths, and to prolonging the pandemic.

Your location

Your location or check-in on social media may not only increase the risk to yourself and your loved ones of physical danger, but may help criminals launch virtual kidnapping attacks and other social engineering scams.

In addition, an image of you in a place frequented by people of certain religious, sexual, political, cultural, or other affiliations can lead to criminals extrapolating information about you that may lead to all sorts of social engineering. Criminals are known, for example, to have virtually kidnapped a person who was in synagogue and unreachable on the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur. They knew when and where the person would be walking to the temple, and called family members (at a time that they knew the person would be impossible to reach) claiming to have kidnapped the person. The family members fell for the virtual kidnapping scam because the details were right and they were unable to reach the “victim” by telephone in the middle of a synagogue service.

Your birthday

A happy birthday message to someone on social media may reveal the person’s birthday. Folks who use fake birthdays on social media for security reasons have seen their precautions undermined in such a fashion by would be well-wishers.

Your “sins”

Anything that is “sin-like” may lead not only to professional or personal harm, but to blackmail-like attempts as well as social engineering of yourself or others depicted in such posts or media. If in doubt, be careful. Something you post that may be questionable today might be considered nothing short of repugnant in the future; old posts cause people personal and professional harm on a regular basis.

Leaking Data by Sharing Information as Part of Viral Trends

From time to time, a viral trend occurs, in which many people share similar content. Posts about the ice bucket challenge, your favorite concerts, and something about you today and ten years ago are all examples of viral trends. Of course, future viral trends may have nothing to do with prior ones. Any type of post that spreads quickly to large numbers of people is said to have “gone viral.”

Identifying Fake Social Media Connections

Social media delivers many professional and personal benefits to its users, but it also creates amazing opportunities for criminals — many people have an innate desire to connect with others and are overly trusting of social media platforms. They assume that if, for example, Facebook sends a message that Joseph Steinberg has requested that they become his friend, that the real “Joseph Steinberg” has requested such — when, often, that is not the case.

Criminals know, for example, that by connecting with you on social media, they can gain access to all sorts of information about you, your family members, and your work colleagues — information that they can often exploit in order to impersonate you, a relative, or a colleague as part of criminal efforts to social engineer a path into business systems, steal money, or commit other crimes.

One technique that criminals often use to gain access to people’s “private” Facebook, Instagram, or LinkedIn information is to create fake profiles — profiles of nonexistent people — and request to connect with real people, many of whom are likely to accept the relevant connection requests. Alternatively, scammers may set up accounts that impersonate real people — and which have profile photos and other materials lifted from the impersonated party’s legitimate social media accounts.

How can you protect yourself from such scams? The following sections offer advice on how to quickly spot fake accounts — and how to avoid the possible repercussions of accepting connections from them.

Photo

Many fake accounts use photos of attractive models, sometimes targeting men who have accounts that show photos of women and women whose accounts have photos of men. The pictures often appear to be stock photos, but sometimes are stolen from real users.

You can also search on the person’s name (and, if appropriate, on LinkedIn) or title to see whether any other similar photos appear online. However, a crafty impersonator may upload images to several sites. Obviously, any profile without a photo of the account holder should raise red flags. Keep in mind, though, that some people do use emojis, caricatures, and so on as profile photos, especially on nonprofessional-oriented social media networks.

Verification

If an account appears to represent a public figure who you suspect is likely to be verified (meaning it has a blue check mark next to the user’s account name to indicate that the account is the legitimate account of a public figure), but it is not verified, that is a likely sign that something is amiss. Likewise, it is unlikely that a verified account on a major social media platform is fake. However, there have been occasions on which verified accounts of such nature have been taken over temporarily by hackers.

Friends or connections in common

Fake people are unlikely to have many friends or connections in common with you, and fake folks usually will not even have many secondary connections (Friends of Friends, LinkedIn second level connections, and so on) in common with you either.

Relevant posts

Another huge red flag is when an account is not sharing material that it should be sharing based on the alleged identity of the account holder. If someone claims to be a columnist who currently writes for Forbes, for example, and attempts to but has never shared any posts of any articles that they wrote for Forbes, something is likely amiss.

Number of connections

A senior-level person, with many years of work experience, is likely to have many professional connections, especially on LinkedIn. The fewer connections that an account ostensibly belonging to a senior level person has on LinkedIn (the further it is from 500 or more), the more suspicious you should be.

Of course, every LinkedIn profile started with zero connections — so legitimate, new LinkedIn accounts may seems suspicious when they truly are not — but practical reality comes into play: How many of the real, senior-level people who are now contacting you didn’t establish their LinkedIn accounts until recently? Of course, a small number of connections and a new LinkedIn account isn’t abnormal for people who just started their first job or for people working in certain industries, in certain roles, and/or at certain companies — CIA secret agents don’t post their career progress in their LinkedIn profiles — but if you work in those industries, you’re likely aware of this fact already.

Industry and location

Common sense applies vis-à-vis accounts purporting to represent people living in certain locations or working in certain industries. If, for example, you work in technology and have no pets and receive a LinkedIn connection request from a veterinarian living halfway across the world whom you have never met, something may be amiss. Likewise, if you receive a Facebook friend request from someone with whom you have nothing in common, beware.

Similar people

If you receive multiple requests from people with similar titles or who claim to work for the same company and you don’t know the people and aren’t actively doing some sort of deal with that company, beware. If those folks don’t seem to be connected to anyone else at the company who you know actually works there, consider that a potential red flag as well.

Duplicate contact

If you receive a Facebook friend request from a person who is already your Facebook friend, verify with that party that that person is switching accounts. In many cases, such requests come from scammers.

Contact details

Make sure the contact details make sense. Fake people are far less likely than real people to have email addresses at real businesses and rarely have email addresses at major corporations. They’re unlikely to have physical addresses that show where they live and work, and, if such addresses are listed, they rarely correspond with actual property records or phone directory information that can easily be checked online.

Premium status

Historically, criminals avoided paying for paying for premium service for their scam accounts. Because LinkedIn charges tens of dollars per month for its Premium service, for example, some experts have suggested that Premium status is a good indicator that an account is real because a criminal is unlikely to pay so much money for an account.

While it may be true that most fake accounts don’t have Premium status, some crooks do invest in obtaining Premium status in order to make their accounts seem more real — especially if they plan to use the accounts to engage in targeted attacks. In some cases, they are paying with stolen credit cards, so it doesn’t cost them anything anyway. So, remain vigilant even if an account is showing the Premium icon.

LinkedIn endorsements

Fake people are not going to be endorsed by many real people. And the endorsers of fake accounts may be other fake accounts that seem suspicious as well.

Group activity

Fake profiles are less likely than real people to be members of closed groups that verify members when they join and are less likely to participate in meaningful discussions in both closed and open groups on Facebook or LinkedIn. If they are members of closed groups, those groups may have been created and managed by scammers and contain other fake profiles as well.

Fake folks may be members of many open groups — groups that were joined in order to access member lists and connect with other participants with “I see we are members of the same group, so let’s connect” type messages.

Appropriate levels of relative usage

Real people who use LinkedIn or Facebook heavily enough to have joined many groups are more likely to have filled out all their profile information. A connection request from a person who is a member of many groups but has little profile information is suspicious. Likewise, an Instagram account with 20,000 followers but only two posted photos that seeks to follow your private account is suspicious for the same reason.

Human activities

Many fake accounts seem to list cliché-sounding information in their profiles, interests, and work experience sections, but contain few other details that seem to convey a true, real-life human experience.

Here are a few signs that things may not be what they seem:

- On LinkedIn, the Recommendations, Volunteering Experience, and Education sections of a fake person may seem off.

- On Facebook, a fake profile may seem to be cookie cutter and the posts generic enough in nature that millions of people could have made the same post.

- On Twitter, they may be retweeting posts from others and never share their own opinions, comments, or other original material.

- On Instagram the photos may be lifted from other accounts or appear to be stock photos — sometimes none of which include an image of the actual person who allegedly owns the accounts.

Likewise, if you perform a Google image search on someone’s Instagram images and see that they belong to other people, something is amiss.

Cliché names

Some fake profiles seem to use common, flowing American names, such as Sally Smith, that both sound overly American and make performing a Google search for a particular person far more difficult than doing so would be for someone with an uncommon name.

Poor contact information

If a social media profile contains absolutely no contact information that can be used to contact the person behind the profile via email, telephone, or on another social platform, beware.

Skill sets

If skill sets don’t match someone’s work or life experience, beware. Something may seem off when it comes to fake accounts. For example, if someone claims to have graduated with a degree in English from an Ivy League university, but makes serious grammatical errors throughout their profile, something may be amiss. Likewise, if someone claims to have two PhDs in mathematics, but claims to be working as a gym teacher, beware.

Spelling

Spelling errors are common on social media. However, something may be amiss if folks misspell their own name or the name of an employer, or makes errors of this nature on LinkedIn (a professionally oriented network).

Age of an account

Does the age of the account make sense considering to whom the account allegedly belongs? If you come across an active Instagram account belonging to some attractive person whom you met on a dating site, and the account has shared many photos, but all of the photos were uploaded within the last few weeks, ask yourself if it makes sense that the person in question did not post photos before that date. You may have encountered a “catfish” as explained in Chapter 4.

Suspicious career or life path

People who seem to have been promoted too often and too fast or who have held too many disparate senior positions, such as VP of Sales, then CTO, and then General Counsel, may be too good to be true.

Of course, real people have moved up the ladder quickly and some folks (including myself) have held a variety of different positions throughout the course of their careers, but scammers often overdo it when crafting the career progression or role diversity data of a bogus profile. People may shift from technical to managerial roles, for example, but it is extremely uncommon for someone to serve as a company’s VP of Sales, then as its CTO, and then as its General Counsel — roles that require different skill sets, educational backgrounds, and potentially, different certifications and licenses.

Level or celebrity status

LinkedIn requests from people at far more senior professional levels than yourself can be a sign that something is amiss, as can Facebook friend requests from celebrities and others about whose connection request you’re flattered to have received.

It is certainly tempting to want to accept such connections (which is, of course, why the people who create fake accounts often create such fake accounts), but think about it: If you just landed your first job out of college, do you really think the CEO of a major bank is suddenly interested in connecting with you out of the blue? Do you really think that Ms. Universe, whom you have never met, suddenly wants to be your friend?

In the case of Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, be aware that most celebrity accounts are verified. If a request comes in from a celebrity, you should be able to quickly discern if the account sending it is the real deal.

Using Bogus Information

Some experts have suggested that you use bogus information as answers to common challenge questions. Someone — especially someone whose mother has a common last name as her maiden name — may establish a new, substitute “mother’s maiden name” to be used for all sites that ask for such information as part of an authentication process. There is truth to the fact that such an approach somewhat helps reduce the risk of social engineering.

What such advice does in a much stronger fashion, however, is reveal how poor challenge questions are as a means of authenticating people. Asking one’s mother’s maiden name is effectively asking for a password while providing a hint that the password is a last name!

Likewise, because in the era of social media and online public records, finding out someone’s birthday is relatively simple, some security experts recommend creating a second fake birthday for use online. Some even recommend using a phony birthday on social media, both to help prevent social engineering and make it harder for organizations and individuals to correlate one’s social media profile and various public records.

While all these recommendations do carry weight, keep in mind that, in theory, there is no end to such logic — establishing a different phony birthday for every site with which one interacts offers stronger privacy protections than establishing just one phony birthday, for example. But how many “birthdays” can one remember? And besides, all using multiple fake birthdays does is effectively transform the authentication-using-birthday into a authentication using a second password — albeit one that is weak and has only 366 possible values.

Using Security Software

Besides providing the value of protecting your computer and your phone from hacking, various security software may reduce your exposure to social engineering attacks. Some software, for example, filters out many phishing attacks, while other software blocks many spam phone calls. While using such software is wise, don’t rely on it. There is a danger that if few social engineering attacks make it through your technological defenses, you may be less vigilant when one does reach you — don’t let that happen.

While smartphone providers have historically charged for some security features, over time they have seen the value to themselves of keeping their customers secure. Today, basic versions of security software, including technology to reduce spam calls and to scan apps for malware, are often provided at no charge along with smartphone cellular-data service. Premium offerings still exist and are often worthwhile to use.

General Cyberhygiene Can Help Prevent Social Engineering

Practicing good cyberhygiene in general can also help reduce your exposure to social engineering. If, as so commonly happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, your children, for example, have access to your computer but you encrypt all your data, have a separate login, and don’t provide them with administrator access, your data on the machine may remain safe even if criminals social engineer their way into your child’s account.

Likewise, not responding to suspicious emails or providing information to potential scammers who solicit it can help prevent all sorts of social engineering and technical attacks.

Unless you are using an email security system that overcomes such issues with digital signatures and other security technologies, when you receive an email from someone, you are not actually receiving the email from that person. Your computer is simply telling you that another computer told it, based on what another computer told it, based on what another computer told it, and so on, that the person who is the “sender” actually sent you the included message.

Unless you are using an email security system that overcomes such issues with digital signatures and other security technologies, when you receive an email from someone, you are not actually receiving the email from that person. Your computer is simply telling you that another computer told it, based on what another computer told it, based on what another computer told it, and so on, that the person who is the “sender” actually sent you the included message. The following list helps you understand and internalize the methods crooks are likely to use to try to gain your trust:

The following list helps you understand and internalize the methods crooks are likely to use to try to gain your trust: