1

Bigger, Better, Faster, Cheaper

The streets of San Francisco may be tough, but they were not tough enough to deter Travis Kalanick, the pugnacious co‐founder and early CEO of Uber. In fact, the street part was a lot easier than the politics. When the ridesharing website UberCab appeared in 2010, it was an immediate hit. But after its official launch a year later, the company was forced to change its name to Uber after taxicab drivers, who had spent thousands of dollars for their government‐issued medallions and had to comply with municipal regulations, complained about the competition.

That was just the first of many battles. As Uber expanded into multiple cities in the United States and morphed from a “black car” limousine ridesharing service into one that set up ride‐hailing with independent operators, the fights continued, with the aggressive company continuing to skirt the edges of established regulation. Local municipalities and their taxicab interests pushed back, but Uber generally prevailed, as consumers enjoyed the easy‐to‐use service. When state legislatures got involved, as California's did in 2019 by requiring platforms to treat “gig economy” workers like employees, Uber took to the streets politically, leading and winning a ballot initiative that created a ridesharing exemption the following year. In other cases where resistance was strong, the company argued that it was simply a technology platform, not a service, and thus exempt from other regulations and restrictions. And it was not afraid to take aim at crosstown rival Lyft at any time.

In fact, Kalanick and the company almost seemed to relish the battles with regulators, adopting an approach that was purportedly called “Travis's Law”: Our product is so superior to the status quo that if we give people the opportunity to see it or try it, in any place in the world where government has to be at least somewhat responsive to the people, they will demand it and defend its right to exist.1

Kalanick himself was controversial, and he was forced to step down in 2017 after a series of revelations of inappropriate behavior at the company under his leadership. Nevertheless, with a combination of quick consumer adoption of its innovative app and substantial sums of venture capital, Uber rocketed to success in the United States and expanded globally.

Outside the United States, by contrast, the company's entrepreneurial disruption met determined opposition. In London, where taxicab drivers must adhere to strict licensing and conduct codes, the company discontinued its car operations in 2017 and did not resume operations until four years later when a British Supreme Court decision allowed it back in. Meanwhile, local European companies tried to build up operations in their home countries or other locations where Uber was not yet strong. Hailo made early progress in London by partnering with taxi operators but ultimately merged with a German company to form what today is FREE NOW. BlaBlaCar in France had some early success but stayed focused on the ridesharing and struggled. The Estonian company Bolt, founded in 2013, expanded to 300 cities and 45 countries, but it was late to the game. These companies gained traction, but continued regulatory challenges in many of their markets and limited capital kept them from expanding aggressively. At the end of 2021, FREE NOW had a market valuation at around $1 billion, BlaBlaCar at roughly $2 billion, and Bolt at $5 billion. Uber, in contrast, was worth $85 billion, while its rival Lyft reached $15 billion.

China was another story. In 2012 Didi Dache emerged, backed by powerhouse Tencent Holdings, and quickly achieved market leadership. Kuaidi Dache, with lead investor Alibaba, soon followed. In 2015, the two firms merged, creating the dominant player – rebranded Didi Chuxing – with over 80% market share in what would soon be the world's largest ride‐hailing market. For all their relentlessness, Kalanick and Uber did not stand a chance against the government favorite, and it sold its UberChina division to Didi in 2016 in exchange for roughly an 18% interest in Didi.2

While Uber ceded the Chinese market to the domestic player, it is unclear who will win the global game. In June 2021, Didi went public on the New York Stock Exchange with an initial market value of $70 billion, and appeared to be poised to overtake Uber. But a few weeks later the Chinese government ordered the company to shut down certain of its services out of concerns about data privacy, and the company's app was removed from the major app stores. The restrictions were part of a broader crackdown on technology firms under the country's anti‐monopoly laws, an effort by Premier Xi Jinping to assert control over the emerging private‐sector giants. By Spring 2022, Didi's market value had dropped to $10 billion – less than half the IPO valuation – and the company announced plans to delist from the NYSE and move to the Hong Kong stock exchange.

Birthing Unicorns

Entrepreneurship goes back to ancient times, but the velocity and scale of start‐up activity worldwide has expanded substantially in the past decade. This trend is in large measure due to the success of Silicon Valley technology firms, the ease of idea‐sharing around the world, and the low‐cost access to technology and markets facilitated by the smartphone and the internet. Alongside these success stories, enabling their efforts, venture capital and other sources of funding have grown to unprecedented levels in virtually every major country. The result is a frenzy of start‐up activity across the globe.

Yet the story of Uber and its peers highlights some critical differences in entrepreneurship worldwide. These differences often reflect not just challenges or opportunities related to specific companies or markets, but also systemic differences across countries. These variations indicate deeper and longer‐standing cultural, economic, or political factors, often described by academics who study “varieties of capitalism.” While most of these analyses look at broad factors in the economy, many of the differences are most pronounced when it comes to entrepreneurship and the fate of start‐ups across various regions.3

Despite the buzz of entrepreneurial activity around the world, America still stands out. This leadership includes the country's historic and current ability not just to create new companies at high rates but to empower the most successful of them to grow. As the case of taxis illustrates, the dynamics of competition, access to the market, the ability to raise capital, the power of competitors and other constituencies to resist, and broad political and institutional forces all affect the ultimate success of a venture. When one looks at the results, it is clear that America excels not just in enabling start‐ups but in supporting them to achieve scale. And as one looks at the dynamics at work underneath, the reasons become clear.

The year 2021 was remarkable in terms of start‐up activity, with an astounding $330 billion invested globally – almost double the amount the previous year. And while many countries reached record levels, the United States still represented the dominant share, with nearly half of all the investment going to companies.4

While the creation of large companies is not the only barometer of successful entrepreneurship, the United States continued to lead the world in “unicorns” – privately held ventures that reach the billion‐dollar valuation level – at 400. Most other nations lag by a wide margin: India counts 38, the United Kingdom 31, Germany 18, Israel 18, France 17, Canada 14, Brazil 13, and South Korea 10.5 Moreover, as of the end of 2021, the U.S. has given rise to 8 of the 11 companies worldwide with market valuations above $1 trillion.

Certainly, some of this is changing, as countries and investors are awakening to opportunities to build exciting businesses in markets around the globe. But it is not clear how these companies will fare over time and whether the enterprises that emerge in this frenzy will unleash a continual cycle of innovation and entrepreneurship in their countries that will endure beyond those firms, or simply devolve into stagnant industry incumbents once they reach the top.

It is particularly interesting to consider these statistics in light of China's rise. At 158 unicorns, China is the only nation that comes close to the United States and may soon overtake it – albeit with four times the population. However, recent issues such as the crackdown on the large technology firms, the temporary detention of Ant Group founder Jack Ma, the restrictions on civil liberties in Hong Kong, and the Evergrande financial crisis all raise questions about the long‐term future off China's entrepreneurial economy and whether authoritarian capitalism and entrepreneurship can coexist over time.

While the long‐term success of entrepreneurship in other parts of the world remains an open question, American leadership in this area is clear and has been an important pillar of its development since inception. How do we understand America's remarkable support and encouragement of entrepreneurship?

Historians and other experts have laid out several contributing factors. The country's open frontiers, with virgin land and other natural resources, invited growth and created a culture of expansion.6 Moreover, from the very beginning, the country desperately needed people to work the land and later to help build out its infrastructure. As a result, the nation developed a culture the that offered people opportunities and welcomed a steady flow of talented immigrants, restless enough to leave their own countries and willing to take on new opportunities.7 Substantial public investment in infrastructure, research institutions, and fundamental science likewise have been essential to developing many new industries.8

Yet these factors alone do not suffice to explain the wave after wave of entrepreneurial activity in the history of American capitalism. After all, the United States is not the only large, immigrant‐frontier country with a public‐minded and growth‐oriented government. But it stands out for the intensity, breadth, and duration of its entrepreneurial verve. Something else is needed to explain how the country has been able to empower people to chase after bold dreams, risking financial resources and tackling a myriad of other challenges, rather than apply their talents toward contented lives in comfortable settings.

That something else may best be described, ironically, as safety. Or at least safety in taking risks and investing the time, talent, and energy in pursuit of dreams. In most other countries, entrepreneurs often face major challenges, impediments, and barriers to entry when it comes to starting businesses. They must overcome stiff or capricious licensing requirements, burdensome regulation, and a weak transportation and financial infrastructure (including access to capital). And should these entrepreneurs falter, they have to deal with devastating liability or even social disgrace.

More significantly, America's cultural, legal, and political systems give entrepreneurs the room to succeed and grow, even if that means pushing up against strong, established foes. In many countries, new enterprises, especially innovative or disruptive ones, often face powerful forces of resistance or co‐optation, whether at the national or local level. In some countries, this includes the possibility that government authorities might prevent or deter the new competitive enterprise or even expropriate successful ones. In other countries, especially in more developed ones, the resistance is subtle. Since innovative firms often upset the apple cart, a range of actors including large established firms, small businesses, workers, suppliers, and even customers may object, and these forces of resistance create deterrents through the political and institutional system.9 Aspiring innovators often have little recourse.10

An important corollary to America's pro‐start‐up culture is its inherent opposition to cronyism and monopoly. As discussed later, America has a strong tradition against protectionism at both the local and national levels. While companies no doubt can be effective in garnering and using political influence, citizen‐consumer interests have largely prevailed over time, giving innovators and competitors access to the marketplace at any level while also creating a larger market overall. The result has been greater innovation, productivity, and efficiency, as well as a sustained and continuous cycle of new enterprise.

Would‐be crony capitalists are not the only ones vulnerable to new companies and emerging innovations; here, as elsewhere, other constituents and interest groups, including workers and small business, often resist entrepreneurs. While these groups are sometimes quite powerful and effective in using the political process to deter change, they are usually unable to stop new companies or innovations from finding their way into the market, especially if consumers are directly impacted. Among all the many potential forces of resistance, the relative paucity of protection for incumbents is perhaps the most noteworthy difference between America's dynamic entrepreneurial economy and nearly all other competitive economies.

Slaying Dragons

It may seem ironic that even as America spawns more unicorns than other countries, it also is more lenient in allowing large and successful firms to fail. But this underside – the “destruction” component in Joseph Schumpeter's famous formulation – is actually an essential part of the equation. Not only does the hypercompetitive market economy of the United States allow upstarts to challenge incumbents and sometimes win, but the intensity of the competition, and the relatively few ways for incumbents to seek protection, forces those large companies to “stay on their toes.”11 Part of what drives unicorns is the recognition that they may themselves be vulnerable.

It is not a coincidence that while the United States saw more unicorns emerge in the last several years, it also witnessed significant failures of some of its largest and most powerful companies. Even General Electric, a mainstay on the Dow Jones Industrial Average for a century, fell from the index in 2018, preceded by such giants as AT&T, Sears, and General Motors. A study of publicly traded firms on the Standard and Poor's 500 index found that the average “corporate lifespan” is at an all‐time low and continues to decline.12 Amidst the growth of powerful new companies, America's “churn rate” among large firms is higher than elsewhere.

As will be discussed later in the book, there are many reasons why large and powerful incumbents decline. New disruptive technologies might change the underlying economics of a product or market, and established firms have difficulty identifying or adopting to the change. In other cases, corporate bureaucracy, incentive systems, or plain bad luck exact a toll. But the key feature of the American business environment is that, in general, we do not prop up faltering companies and we allow even the largest and most powerful firms to fail.

The difference between the United States and most of the world is striking in this regard. In much of the developing world, inefficient or corrupt governments, along with conservative cultural norms and unclear property rights, stifle entrepreneurship, whether the small business variety or innovative start‐ups.13 In some countries, authoritarian regimes offer stability, but with greater risk of confiscation or favoritism – especially for companies with big ambitions. Successful firms often become aligned with the state. Even in fast‐growing “entrepreneurial nations,” the state often promotes “national champions,” frequently at the expense of true dynamism. China and India have witnessed an explosion of start‐ups and the emergence of large, powerful companies, but most of the success stories are tied to the political power base. It remains unclear whether newer entities in these countries will be able to challenge incumbents or, just as important, whether these rising firms will stagnate due to the lack of serious challengers as they obtain and protect a leading market position.14

Even the most liberal, Westernized countries have failed to support the level of dynamism seen in America. Germany and Japan are thriving, but they tend to encourage static consortiums of firms and supporting business networks, often as part of concerted national policies. Their leading companies have typically existed for decades and are aligned with the government, major banks, and employee unions. Supplier networks are vibrant and competitive (the German Mittelstand firms and members of Japanese keiretsu come to mind), but without the winner‐take‐all dynamism that encourages risk‐taking in the United States. France has wrestled with liberalizing, but many incumbents remain entrenched and small business incumbents are politically powerful. The United Kingdom's economy is also largely static and facing challenges to its leadership role in capital markets due to Brexit. To be sure, many European cities have recently seen a high level of entrepreneurial activity – Berlin, Stockholm, London, and Paris have particularly active start‐up scenes – but none have yet demonstrated the U.S.'s relentless cycle of start‐ups challenging incumbents over decades.

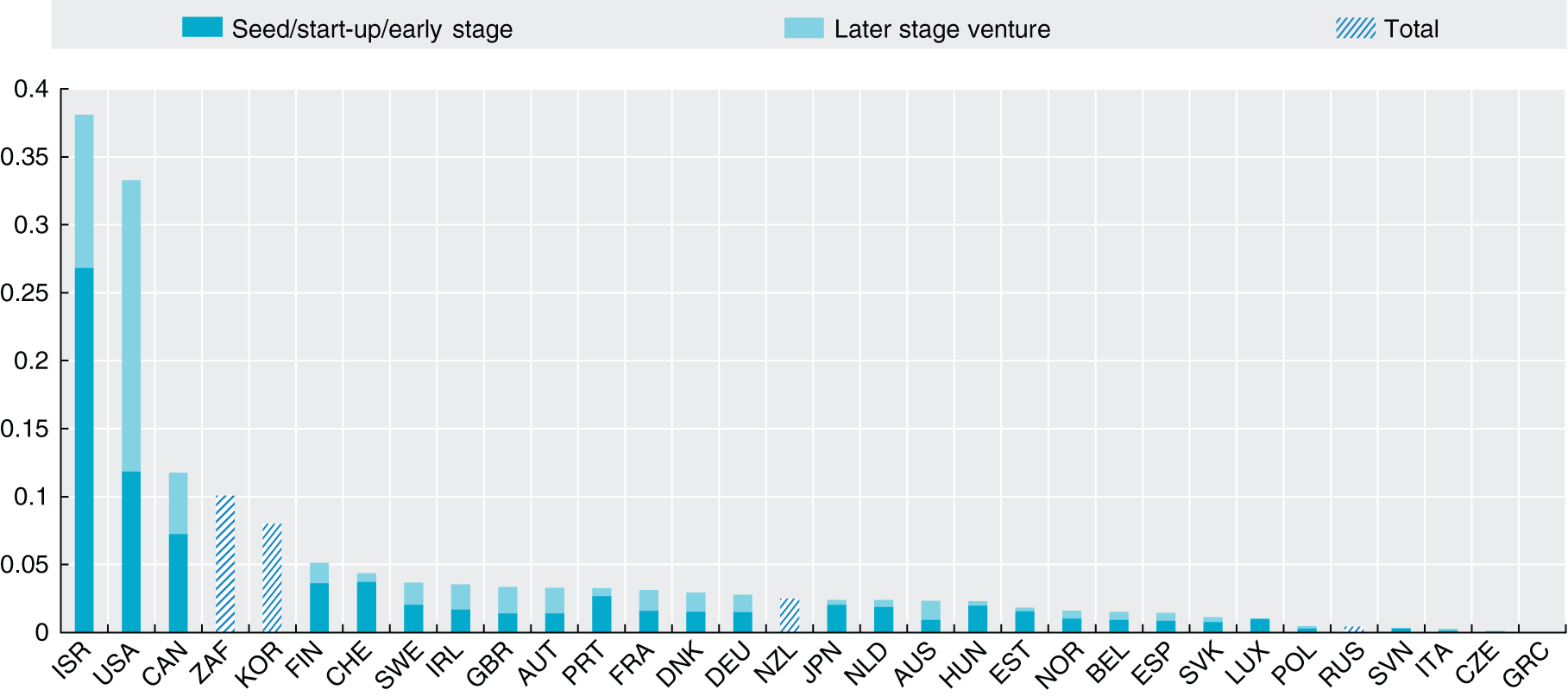

The closest comparison to the United States in this regard is Israel, a small country with an impressive level of innovation from many venture‐backed firms. As noted in a top‐selling book on the topic, this “start‐up nation's” dynamic and assertive culture has been perhaps its most powerful asset. But Israel's export‐intensive high‐tech economy means it avoids confronting dominant incumbents as new firms develop. As a result, while it is intensely competitive, it doesn't face the opposition of established domestic rivals typical in most large developed countries. Israel is the exception that proves the rule.15 (See Figure 1.1, Venture Capital as a % of GDP by Country.)

Challenging and Limiting Authority

Underlying the balancing act between upstarts and incumbents is the seldom appreciated tension between two central principles in American political economy: the right to property and the right to compete. While often at odds, these principles emerged together centuries ago out of a general mistrust of powerful authority, especially monarchy. Both principles check the possibility of government overreach, which is how they became embedded in the U.S. constitution at the nation's founding.

The American adoption of these principles emerged from long‐running traditions dating back to the feudal system, most notably in England. Early property rights were recognized in 1215 in the Magna Carta, which protected the interests of the nobility from monarchical invasion. This concept of secured interest and limited royal prerogative carried over later to firming up property rights related to the issuance of royal grants and charters during the age of exploration.16 Wealthy gentry worried that central authorities would confiscate personal property, while venturers sought certainty before investing time and resources to risky endeavors. Over time, these protections expanded to other enablers of commercial activity such as contracts, insurance, and financial instruments, as well as patents for inventions.17

Compared with classic property rights, the right to compete is a nebulous concept, but it too has deep roots. The modern sense of economic competition as a positive social force emerged in the early modern period of European history, long after widespread recognition of property rights. The right to compete took shape initially from the questioning of scientific and religious authority during the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, and soon broadened into commerce.18 The development of guilds also led to early issues regarding the ability or right to conduct trade. The controversy over the enclosure movement in the 16th century, pitting landowners fencing in their lands against peasants who traditionally had grazed livestock there, is one example where property interests were both asserted and challenged. These developments culminated in the early 1600s backlash against Queen Elizabeth I, whose reliance on patents limited opportunity and fostered resentment among aspiring gentlemen and commoners. Building on this resentment, both John Locke and Adam Smith proclaimed the right to pursue a trade as an inherent, natural right.

Figure 1.1 Venture capital as a percentage of gross domestic product by country.

Source: OECD Capital Series, “Entrepreneurship at a Glance, 2016.”

The assertion of property rights (specifically the limit on royal confiscation) and the right to compete (especially against overreaching royal grants) gained momentum with England's Glorious Revolution of 1688. Besides limiting the power of the monarch to confiscate property, the revolution brought a Bill of Rights. Among the changes was a radical restructuring of the British East India Company, the dominant commercial enterprise of its day, to end its domestic (though not international) monopoly rights.19

Both property rights and the nascent right to compete carried over to America, and the scope of these two rights and principles have continued to evolve. Classic property rights such as those related to the ownership of land have expanded into questions such as the ability of a company to determine retail prices, a software company to bundle products, a smartphone or automobile manufacturer to determine who can make repairs, or a technology company to parlay data into new services. The right to compete has been asserted in areas such as market access and “fair” competition, in some cases arguing the exact flipside of classic property rights. How the right to compete evolved and developed, not just as a complement to property rights but as a challenge to it, and how the American political and legal systems have responded to this tension, is essential to understanding how the American economy actually generates progress.

The interplay of these rights altered not just the political and economic landscape but also the social order, where “new money” often pitted itself against “old money.” At times, entrepreneurs threatened the wealth or standing of individuals with far‐reaching influence. Schumpeter noted how creative destruction upsets the social pecking order, with entrepreneurs continually taking on dominant interests and knocking them off their proud perches.20 Today, wealthy individuals can manage this risk by diversifying their activities, so the dynamic is not quite the same zero‐sum game it may have been in the past. And often entrepreneurs supersede rather than disrupt, raising the bar and keeping incumbents fresh and vigilant rather than dismantling them. The striving and success of entrepreneurs can thus have far‐reaching effects well beyond just the economic sphere, including politics.

A Political Economy of Competing Interests

In the 1950s, political scientist Louis Hartz noted that the United States features a long‐standing tradition of limited government involvement in the lives of its citizens. Hartz and others identified the key attributes of this tradition as a strong orientation toward individualism, the absence of an embedded aristocratic class, and an egalitarian approach toward social and political life. Personal liberty and rational self‐interest constitute the essence of the American culture.21

This liberal tradition plays out in economic life as well, and the political and economic system embodied by the Constitution largely allowed “private ordering” in the area of economic affairs. It also allowed – some might say even encouraged – a competition of interests. Both the entrepreneurial economy and the political system involve balancing acts. In politics, the country aims to avoid both the extremes of popular democracy, which infringes on the rights of minority groups of all kinds, and the extremes of rule by elites, which suppresses the interests of the populace. Economically, we likewise avoid favoritism toward upstarts, which would undercut the property and other rights of established firms, and favoritism toward incumbents, which would hinder upstarts from mounting challenges. It achieves this balance not through benevolent rulers or even an explicit consensus but through an adversarial and competitive process. As in the realm of politics, the economic system allows competing interests to be heard, with the ultimate goal of stimulating growth and productivity gains. The result is more dynamism, innovation, and social mobility.

These political and economic systems have reinforced each other over time. The democratic political structure balances power and protects individual rights, thereby enabling competing factions to play themselves out. It self‐corrects its excesses, if not immediately then over time. Similarly, in the economic realm, the balance between upstarts and incumbents may break down for brief periods, but neither incumbents nor upstarts have succeeded in capturing political (and in most cases economic) power over a sustained period. In fact, James Madison's Federalist No. 10, written in support of the Constitution and often cited in support of competing political interests, explicitly applied the concept to the economic sphere.22

Critics will accurately point to glaring exceptions when the balance of competing interest fell out of whack, but history shows that even the most powerful firms have eventually petered out, most often due to new firms or innovations that undercut their market position. In rare cases when companies maintain their position within an industry for decades, new industries emerge to supersede them, and the once dominant firms still exist but in a secondary segment of the economy. The stubborn dominance of oil companies is one example of persistent incumbency, with entrepreneurial energy now moving the economy toward green energy alternatives.

Over the last several years, the role of big firms in the political process has gained a lot of attention. The Citizens United decision gave corporate entities additional rights in the area of campaign finance, and large technology firms have assembled “armies” of lobbyists. More recently, some large companies have become active in pushing for voting rights in certain states, to cheers in some quarters and legislation in others calling for limits on “woke corporations.” While many people equate special interests and lobbying with large firms, in fact trade groups such as those for real estate brokers and car dealers are among the most active business lobbyists, at both the national and local levels.23

In truth, the political influence of business interests has been less potent in the United States than in other countries, a fact noted long ago by Mancur Olson, a pioneer in studying interest group politics.24 Olson warned of the risk that powerful interests pose to both democracy and the economy, while noting that this has largely been avoided in the United States. Most special‐interest pressures have worked in niche areas such as administrative rulemaking and regulation. Broad co‐optation of government is difficult in an economy so large and diverse. Ultimately, the best way to keep money out of politics is to keep politics out of money, so to speak. But if some intersection between the two is inevitable, the process of competing interests will remain essential both to democratic resilience as well as economic dynamism.

The link between political and economic systems is familiar to scholars of political economy and the field of institutional economics, which argues that the “rules of the game” defined by governments and institutional agreements shape the nature and contours of economic development.25 But the specific connection between entrepreneurial dynamism and those rules has not been articulated. A recent best‐selling book about economic development across nations and history, which distinguished between “inclusive” and “exclusive” forms of government and economic activity, suggested some of the broad themes described here.26 Several policy books have identified differences among political economies and have made recommendations keep American competitive and to assist countries that seek to replicate our success.27 Yet a detailed understanding of America's specific institutional dynamics, its historical context, and the nature of entrepreneurial competition will make those recommendations more effective.

The great feat of the American entrepreneurial political economy is in remaining stable and secure enough to attract investment and risk‐taking, while welcoming new approaches that challenge existing companies both big and small. Entrepreneurs from Cornelius Vanderbilt to Jeff Bezos can enter an industry and take customers away from the established firms, and those firms (usually) have little recourse outside of business competition. Those emerging entrepreneurs can go on to build large companies and direct enormous investments, with little fear that governments will confiscate or undermine their gains. They can leverage those gains into powerful market positions, subject to certain limitations. They need only fear other major competitors or the inevitable upstarts trying to repeat the process. Or, in many cases, their own inability to adapt. America's system is seldom straightforward, as market conditions change, information is often imperfect, political compromises are frequently required, and legal cases rarely tee up issues in a perfect or timely manner. The balanced government framework means that the various branches rarely move in lockstep, but the messy process generally works issues out over time.28

Other countries have enjoyed golden eras in which vibrant economic activity flourished for periods up to several decades or even a century. But what's remarkable about America's story is the relentless series of upstarts, disruption, and renewal, even as large companies emerged and succeeded. These upstarts often came up against vested interests, whether large powerful companies, small local businesses, or workers, who sought political and legal mechanisms to defend their turf. Yet enough of the upstarts prevailed to keep the waves of economic renewal flowing. And, perhaps ironically, large companies and even some small ones were still able to thrive by staying on their toes. Behind all of these changes has been a legal, political, and institutional system that adapted to and even encouraged this dynamism.

Key Features of the American Entrepreneurial Economy

This freedom to invest, grow, and ultimately become an incumbent – but not becoming so entrenched as to impede the next generation of innovators – is essential to American capitalism. How did our political economy balance the right of upstarts to compete with the right of established firms to protect their property, when other countries have fallen into business anarchy or a stultifying favoritism toward incumbents? This book explains the persistence of the upstart‐incumbent balancing act and unique American triumph of entrepreneurship by identifying the distinct features of American life and democratic institutions:

- The cultural bias: America began as a commercial venture as much as a religious refuge, and the spirit of enterprise has persisted throughout its history. It proved critical to its anti‐establishment founding and to its western expansion. We prize the self‐made individual and his or her success. Our strong anti‐royalist tradition soon manifested itself as both a distrust of government and an opposition to monopoly, which eventually evolved into a suspicion of powerful corporations. And political and administrative mechanisms have valued innovation and progress over stability and other worthy causes. We favor dynamism, whether in the scrappy little firm or the large corporation, while also respecting hard‐earned gains.

- The political foundations: Sustained entrepreneurship has depended not just on democratic freedoms but on the country's specific institutional framework. The constitution separated federal powers and created an independent judiciary. Patent protections, prohibitions on titles of nobility, restraints on government confiscation without due compensation, and term limits for presidents all fostered openness while safeguarding property rights. The federalist system of government, which kept state and federal government in tension, made cronyism harder to sustain at both the local and national levels, while enabling the development of national markets. The Bill of Rights and individual freedoms encouraged people to pursue their dreams and assert their independence. And the common law system empowered action better than the more restrictive top‐down civil code regimes.

- Decentralized, risk‐enabling finance and corporate governance: Compared to most other affluent countries, the United States has had a fragmented system of channeling savings into investment. Instead of a strong central bank complemented by a few nationwide commercial and investment institutions, the country features a hodge‐podge of local, state, and national banks, though the number of small banks has been declining. Stock exchanges began early, first in Philadelphia and then in New York. Equity finance was particularly important, as was the ability of large fiduciary investors to take risks. Innovations in the corporate law and the establishment of the “prudent man” rule for investment pools in the 19th century, the creation of venture capital and high‐yield “junk” bonds in the 20th century, and other supporting mechanisms fueled an ongoing stream of new enterprises. The legal system also evolved to facilitate these ventures. Contract law and open general incorporation statutes enabled private exchange and supported risk capital. Limits on interlocking directorates led by large banks, and the Anglo‐Saxon investor‐driven board model (so different from the Continental European dual board framework, including worker councils) have kept firms more nimble. More recently, America's focus on shareholder capitalism has forced companies to move aggressively and avoid complacency. Even in the area of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) oversight, American companies are driven by shareholder action more than by government directive.

- Support of market access for innovation: While generally allowing companies to use their property as they see fit, Americans have drawn the line at certain attempts to prevent rivals or new entrants from gaining access to markets. Courts have struck down discriminatory freight pricing (railroads), proprietary parts and service agreements (appliances), discriminatory software tie‐ins (Microsoft and Google), and tiered access (telecom's net neutrality). Policymakers have encouraged new platforms to emerge that disrupt even the largest players, with railroads replacing canals, and highways in turn replacing them, from telegraph to telephone to internet, and from radio to broadcast television to cable to streaming. Once the new platforms dominate, the cycle continues.

- Consumers over interest groups: Battles between upstarts and incumbents involve business entities. But in resolving disputes over potentially disruptive innovation or business combinations, the voice of the consumer has weighed heavily. Other countries typically focus on other companies or on workers in areas involving competition. This tends to preserve the status quo even if it means consumers pay more for goods and services. By looking at the diffuse body of consumers, rather than at specific groups, the American approach is much less susceptible to cronyism and more likely to promote productivity gains over the long term.

Tolerating Collateral Damage

The true magic of American entrepreneurial capitalism and political economy, then, is how it fosters continuing cycles of upstarts and incumbents. The system encourages start‐up ventures to enter or create markets by promising to respect the wealth that these entities create, free from government confiscation, even as the most successful of them become quite large and profitable. It also limits the ability of these companies to protect their position against the next wave of upstart challengers. By striking this unique balance, America has enjoyed sustained economic growth, productivity improvements, and innovation throughout most of its history. This support of innovation, risk‐taking, and development spurred entrepreneurship from the country's very beginning, reinforcing a culture of entrepreneurship and what has been termed the continuous “release of creative human energy.”29

But the American system is neither perfect nor easy to maintain. By its nature, it creates an ongoing cycle of losers as well as winners. While promoting innovation, productivity, and economic and social mobility, this dynamism yields significant social costs. Many constituencies depend on established companies for employment, for business as suppliers and customers, for tax revenues and other supports to communities, and for general stability and philanthropy.

The disruption can affect both large companies and small businesses, and sometimes both. For instance, in its early days selling books (and still today), Amazon competed against both large chain Barnes & Noble (itself once an upstart) and local shops. Whether it is large firms offshoring production or laying off employees to stay competitive, or small businesses shutting down storefronts, entrepreneurship causes real harm.

Muddying the waters further is how upstarts typically morph into incumbents as they grow. Many Silicon Valley firms adopt David‐versus‐Goliath rhetoric on their way up, only to go Goliath as they mature, erecting barriers, squeezing out rivals, and hiring lawyers and lobbyists to protect their interests. The paradox is acute when government policy is involved, such as when upstarts that benefitted from public research, infrastructure, or legal decisions later complain about intrusive government oversight. There is irony, if not outright hypocrisy, when an enterprise like Google touts “Don't Be Evil” as its dictum during the early years and then goes on to hire corporate lobbyists to protect its interests. Yet this is a common part of the journey from upstart to incumbent.

Perhaps the most difficult challenge associated with the American entrepreneurial economy is the impact on workers. For sure, new enterprises add employment, and the largest and most successful can create tens of thousands of jobs, many with employee stock ownership. In addition, a number of the new companies, especially the controversial “platforms” that disrupt the foundations of industries, can spawn a whole range of new satellite entities that master new tools and technologies. Today, thousands of companies have been enabled by platforms such as eBay, the Apple Store, or Amazon marketplace, gaining access to a large market in ways unimaginable 20 years ago. At the individual level, the “gig economy” is creating jobs with flexibility and a new worker paradigm that changes employment for many. But the costs are real, whether from large company layoffs, small business shutdowns, or “technological unemployment,” and the effect is uneven and often unfair. Well‐educated workers in select metropolitan areas are more likely to benefit from the opportunities, while many others are left out. And even some of those who are working within the successful new firms or platforms are pushing for a larger share of the pie, as shown in recent efforts to unionize at Amazon and Starbucks.

Compared with other developed economies, the United States focuses on productivity gains more than on the social safety net. While this may translate into more innovation and often lower costs at the consumer level, it does lead to increased displacement and inequality. This is most pronounced in areas such as health care, unemployment insurance, and education. According to one formulation, Europe suffers from being “too cuddly,” while the United States is “too cutthroat.”30

America's record in sharing its prosperity with all of its citizens is also at best mixed. Without question, the country has an enviable and deserved reputation for providing unlimited opportunity, most often articulated in the American Dream. Upstarts do indeed reach the pinnacles of business at rates much higher than in other countries, and small business has also largely thrived. The success of immigrants is particularly admirable. But America's inclusivity is less enviable when it comes to other groups, particularly women, some minorities, and residents of geographies outside the mainstream of economic life. As protests in 2020 following the killing of George Floyd showed, shortcomings in social and racial justice continue to haunt the country. Finally, as in many other countries, the United States is starting to grapple with climate change and sustainability.31

In addressing these challenges, the biggest issue will be doing so in a way consistent with the liberal tradition of limited government and keeping the country from falling prey to the interest groups and protectionism that prevail elsewhere. Within the increasing global consensus about “softening” capitalism to address issues of sustainability and inequality, countries can take different paths to get there. In the United States, enlisting the help and tradition of entrepreneurship, including social entrepreneurship and “green” entrepreneurship, may produce better outcomes than the government‐directed mandates typical in other countries.

Understanding the features of the American entrepreneurial economy and how it operates is relevant both within and outside the United States. Within the U.S., recognizing the factors enabling entrepreneurial growth will be essential to preserving it while addressing the social challenges. The rise of technological behemoths, and the increasing political role of major corporations, generate headlines daily, as do broader issues around inequality, inclusivity, and climate change. Addressing these issues without killing the goose that laid the golden egg will be the ultimate challenge, while applying our entrepreneurial strengths to solve these problems offers our greatest opportunity.

Beyond America, many countries around the globe are now looking to establish “the next Silicon Valley.” Many take the initial steps to lure entrepreneurial talent and even build successful new companies. They are reproducing the immediate ingredients of a technology cluster with government seed funding, research universities, and perhaps even venture capital. But to succeed over time they must also figure out how to internalize the distinctive economic and political principles at the heart of entrepreneurial dynamism, and understand how the model of the U.S. evolved over the past two centuries.

Endnotes

- 1 Brad Stone, The Upstarts: How Uber, Airbnb and the Killer Companies of Silicon Valley Are Changing the World (New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2017), 195.

- 2 Stone, The Upstarts. See also Rebecca Fanin, The Tech Titans of China: How China's Tech Sector is Challenging the World by Innovating Faster, Working Harder & Going Global (London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing, 2019).

- 3 William J. Baumol, Robert E. Litan, and Carl J. Schramm, Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007). The authors characterize four types of capitalism: state‐guided, oligarchic, big‐firm, and entrepreneurial.

- 4 CB Insights, State of Venture, January 2022. America's share of venture capital investment was approximately 85% in 2004.

- 5 CB Insights, The Complete List of Unicorn Companies, December 2021.

- 6 See, e.g., Richard Kluger, Seizing Destiny: The Relentless Expansion of American Territory (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007).

- 7 Dane Stangler and Jason Wiens, “The Economic Case for Welcoming Immigrant Entrepreneurs,” Ewing Marian Kaufmann Foundation, September 8, 2015. See also David McClelland, The Achieving Society (Princeton: Van Nostrand, 1961).

- 8 See, e.g., Steven Keppler, Experimental Capitalism: The Nanoeconomics of American High‐Tech Industries (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016); Josh Lerner, Boulevard of Broken Dreams: Why Efforts to Boost Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital Have Failed and What to Do About It (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), and Michael Lind, Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United States (New York: HarperCollins, 2012).

- 9 Calestous Juma, Innovation and Its Enemies: Why People Resist New Technology (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- 10 A striking example of an entrepreneur's ability to push through resistance came in 2014, when an immigrant from South Africa, Elon Musk, sued the U.S. Air Force in federal court for refusing to consider a bid from his Space Exploration Technologies company. The Air Force had been content to work with the incumbent consortium of Lockheed Martin and Boeing. The Air Force actually backed down, whereas in other countries it would likely have simply blackballed the presumptuous start‐up. Space X went on to win numerous other contracts for its innovative rockets. It also forced incumbents to reduce their costs. See Christian Davenport, The Space Barons: Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and the Quest to Colonize the Cosmos (New York: Public Affairs, 2018).

- 11 See Baumol, Litan, and Schramm, Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism: “entrepreneurship is an act of dissent,” 85–92; and entrepreneurship constantly churns the pecking order, 115–119 (“Keeping Winners on Their Toes: Playing the Red Queen Game”).

- 12 Innosight, 2021 Corporate Longevity Forecast.

- 13 For a review of certain basic challenges involving property rights in the developing world, see Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else (New York: Basic Books, 2000).

- 14 See Tarun Khanna, Billions of Entrepreneurs: How China and India are Reshaping Their Futures and Yours (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2007); de Soto, The Mystery of Capital; and Baumol, Litan, and Schramm, Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism.

- 15 Dan Senor and Saul Singer, Start‐up Nation: The Story of Israel's Economic Miracle (New York: Hachette Book Group, 2009).

- 16 See Joyce Appleby, The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), 117–118; Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and The Rest (New York: Penguin Press, 2011), Chapter 3, “Property,” 96–139; David Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are so Rich and Some Are so Poor (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999), 32–35 (property rights in Greece, Rome, and the Bible); and Nathan Rosenberg and L.E. Birdzell, Jr., How the West Grew Rich: The Economic Transformation of the Industrial World (New York: Basic Books, 1986), 113–126.

- 17 William Rosen, The Most Powerful Idea in the World: A Story of Industry and Invention (New York: Random House, 2010).

- 18 See, e.g., Rosenberg and Birdzell, How the West Grew Rich, 28; and also Joel Mokyr, “Culture, Institutions, and Modern Growth,” in Sebastian Galiani and Itai Sened, Institutions, Property Rights and Economic Growth (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 182–190.

- 19 Steven Pincus and James Robinson, “What Really Happened During the Glorious Revolution?” in Galiani and Sened, Institutions, Property Rights and Economic Growth, 113–126, 195–196 (new rules and institutions solved the “commitment problem”).

- 20 Joseph Schumpeter, The Theory of Economic Development (London: Transaction Publishers, 1934), 155–156 (the entrepreneur changes the social strata and there is a “loss of caste” for others; noting the American expression of “three generations from overalls to overalls” and that, like a hotel, people at the top are changing forever).

- 21 Louis Hartz, The Liberal Tradition in America (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1955).

- 22 “But the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold and those who are without property have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall under a like discrimination. A landed interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, activated by different sentiments and views. The regulation of those various and interfacing interests forms the principal task of modern legislation and involves the spirit of part and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of government,” Federalist Papers, No. 10.

- 23 Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind, Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press, 2018).

- 24 Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1965) and Olson, The Rise and Decline of Nations (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982). See also Luigi Zingales, A Capitalism for the People: Recapturing the Lost Genius of American Prosperity (New York: Basic Books, 2012), 75–78 (discussing “Tullock's Paradox”).

- 25 See, e.g., Douglass C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Growth (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1971), 48–52.

- 26 Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (New York: Crown Publishers, 2012).

- 27 Baumol, Litan, and Schramm, Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism. Branko Milanovic, Capitalism Alone (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

- 28 Both Vanderbilt and Bezos benefitted from at least implicit government sanction that encouraged innovation. Vanderbilt broke into the steamboat business with the help of a U.S. Supreme Court decision discussed later, and Bezos launched Amazon in part due to a favorable Court decision on sales tax. Both later also benefitted as large incumbents from policies that encouraged infrastructure development in transportation and communications.

- 29 James Willard Hurst, Law and the Conditions of Freedom in the Nineteenth Century United States (Chicago: Northwestern University, 1956), 5–6. Larry Schweikart and Lynne Pierson Doti, American Entrepreneur: Fascinating Stories of the People Who Defined Business in the United States (New York: AMACOM, 1999), 86.

- 30 Philippe Aghion, Celine Antonin, and Simon Bunel, The Power of Creative Destruction: Economic Upheaval and the Wealth of Nations (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2021).

- 31 See, e.g., Irving Kristol, Two Cheers for Capitalism (New York: Basic Books, 1978).