7

The Age and Aging of Incumbents

In the land of the giants, three companies stood the highest. Among the largest enterprises the world had ever known, their combined value dwarfed much of the rest of the economy. By 1907, Standard Oil, American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T), and U.S. Steel were so big that they each controlled well over two‐thirds of the market share of their respective industries. While the federal government took action against all three companies, the results varied enormously.

Standard Oil was the only one to be broken up, yet the resulting entities went on to dominate the energy sector. AT&T avoided breakup by proactively entering into a compromise with the government, one that secured its natural monopoly in long‐distance telephone. It dominated its industry until deregulation finally restored the right to compete to new entrants toward the end of the century. U.S. Steel won its battle with the government and remained the largest corporation in the world for decades, only to be undone by its internal bureaucracy, challenges with the workers union, and new technologies commercialized by upstarts who never lost the right to compete.

Their continuing market dominance stemmed partly from the broad global backdrop. Government‐business relations in the 20th century took place in the context of two world wars, the Great Depression, and a high‐stakes Cold War. In rising to these challenges, the government intervened more aggressively to bolster these large firms than at any point prior – to some extent clipping smaller firms’ right to compete with them. Yet the balancing act ultimately continued as the country avoided the state‐controlled approaches of other countries. When the need to liberalize arose at the end of the century, American society pivoted back to competition and positioned the economy for success.

As described in the previous chapter, Standard Oil substantially reduced prices for users, but its aggressive deals with railroads and creative corporate organization had forced out many small rivals. The Supreme Court's decision in 1911 broke the giant into 34 smaller companies, including the future ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Amoco.

While the government won its case, founder John D. Rockefeller was in many respects the ultimate beneficiary. Standard Oil had already begun to see competition from new entrants such as Texaco, Gulf, Citco, Unocal, and Shell, and its market share had dropped to 65% in 1905. Its progeny, smaller and more agile than the behemoth, had higher profits after the breakup, and Rockefeller's interest in them made him the richest person in the world up to that point.1

AT&T's now‐infamous 1913 “Kingsbury Commitment” with the federal government required only that it divest itself of its Western Union telegraph subsidiary. The giant also had to give local telephone service operators access to its long‐distance network, but the agreement allowed the company to acquire those operators in certain markets. It made over 500 acquisitions over the next two decades.

AT&T's government‐sanctioned monopoly enabled it to become one of the strongest and most powerful companies in America throughout the 20th century, and a mainstay in the economy with over one million American shareholders at its peak.2 But even with this government support and a seemingly “natural monopoly,” the company's protected position could not last. Upstarts kept seeking market entry using new technologies, while a 1956 consent decree with the government forced the company to license its patents royalty‐free. In 1950, the company failed to prevent an inventor from marketing a mechanical device that could be connected to an AT&T telephone.3 In 1968, another upstart won the ability to connect any lawful device, such as answering machines, fax machines, and modems, to the network.4 That decision helped spawn MCI, the first real challenge to AT&T's monopoly on long‐distance phone service itself.

The dam broke in the 1970s, when both MCI and the DOJ sued AT&T on antitrust grounds. MCI won a financial settlement and then raised over $1 billion in high‐yield (“junk”) bonds to enter the market. Separately, AT&T agreed to spin off its seven regional operating companies (the Baby Bells), as well as its Western Electric hardware division. AT&T continued as only the traditional long‐distance firm, now vulnerable to MCI and other upstarts, while gaining the freedom to move beyond long‐distance telephony, including a late‐in‐the‐game effort in computers.5

U.S. Steel was allowed to continue, but with no protection. For many years it was so dominant that it was known simply as “The Corporation.” The government did in fact attempt to limit its power and brought suit in 1911. However, in deciding the case on the heels of World War I, the Supreme Court concluded that “the law does not make mere size an offense.”6 Like many other seemingly dominant incumbents from the great merger movement, the behemoth eventually lost its hard‐charging edge as professional managers took over. Under continuing government scrutiny, stability, not Carnegie's relentless competitiveness, was the order of the day.

Charles Schwab, a Carnegie executive and the first CEO of the company in 1901, soon left in frustration to take over a moribund producer of steel plating, Bethlehem Steel. Rather than compete head‐on, U.S. Steel allowed the new company as well as some other small producers to gradually take market share while preserving its dominance. Schwab and others learned they could operate a profitable business, including exploiting new markets such as structural steel for skyscrapers, as long as they didn't compete aggressively. The incumbent disciplined the upstarts into cooperating in a stable, comfortable oligopoly, aided by high industrial tariffs.7 By the time of the antitrust suit, U.S. Steel's market share had fallen to only 50%.

Though the company remained large and profitable as the industrial economy grew throughout the 20th century, it suffered from the failings of size and embedded technology. It fought battle after battle with the steel workers union, and its reliance on blast furnace technology was disrupted by cost‐effective and flexible electric arc mini‐mills. New entrants could leverage that technology with a clean slate. Moreover, the company proved vulnerable during the Oil Crisis in the 1970s and the emergence of foreign competition in the 1980s. What the government would not or could not do in 1911, the marketplace ultimately accomplished. In 1991 U.S. Steel left the Dow Jones index after a 90‐year run, and it left the S&P 500 index in 2014. Today, it barely makes the list of the world's 40 largest steel producers.

The Push for Bigness

The era of bigness began tentatively with World War I, which showed Americans the payoff from the federal government directing the economy through large enterprises. The war created an abrupt, sharp demand for industrial conversion, and the giants devoted their massive production capacity to the war effort. DuPont, for example, grew its military business by a factor of 236 and the stock prices of many companies increased substantially.8 To coordinate activities, the federal War Industries Board asserted broad temporary powers over business. Business leaders lent management expertise as “Dollar‐a‐Year Men” to answer the exigency. The rapid rise in output convinced many observers that governments could improve on markets, even as the importance of business was evident.

Americans were coming to terms, albeit ambivalently, with a transformed economic landscape.9 “The chief business of the American people is business,” President Calvin Coolidge reminded his constituents in 1925. As trenchant as the Progressive critique of the new industrial behemoths had been, large corporations found themselves at the center of the economy. Instead of dismantling the firms and their enormous productive capacity, American policymakers and judges focused on curbing anti‐competitive abuses, implicitly accepting big business as a reality to work with rather than against.

Upstarts didn't go away, but they focused on new industries not yet caught up in bigness, or they pushed big companies in new directions. Thomas Edison became the iconic inventor‐entrepreneur, while Henry Ford transformed the automobile industry – the cost of vehicles went down significantly and the number of cars on the road skyrocketed. Similarly, electricity altered both consumer and industrial markets. Many of their developments affected consumers directly, in an era characterized as the “democratization and dissemination of the great innovations of laissez‐faire.”10 Several new fields, such as the nascent airline industry, benefitted from government support (in this case mail delivery contracts). But in this era of scale, even those start‐ups aimed at rapid incumbency through size. Over time, these new technologies became platforms for innovation that challenged established industries and incumbent firms, creating opportunities for entrepreneurs much as the railroads did decades earlier.

The consensus for bigness was tested in the 1930s with a new emergency, the Great Depression. While some people blamed large firms for the downturn, most accepted the notion that modern technology and markets required large organizations. Instead of relying on the free market to rationalize through competition, they wanted the government to take an active role, either by closely supervising or perhaps nationalizing key areas. Many urged Washington to follow the European example of acquiring some industries outright and enforcing cartels in others.11

Impressed with business‐government planning in World War I, President Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) initially opted for government‐sponsored cartels. He hoped to build on the lobbying and information‐sharing associations that had spread to much of the economy in the 1920s. He suspected that excessive competition had triggered the downturn, and believed that government intervention would restore confidence and rationalize big business.

With the National Industrial Recovery Act (1933), FDR embarked on an experimental, emergency‐basis program allowing businesses to stabilize prices and thus restore prosperity. The act established the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to oversee industries as they set prices and production levels, improved wages and working conditions, and avoided wasteful competition. Many of the regulations and price controls were drafted with the collective help of industry‐leading incumbents.12 This was not a time for disruptive upstarts to make their mark.

The NRA proved controversial, with opponents ranging from consumer and labor groups to small businesses.13 The Supreme Court's decision in A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935) concluded that the federal government had gone too far in regulating business, in this case setting rules for the sale of whole chickens. The decision was unanimous, as the legislation had delegated to the executive branch power over everything from work hours to local trade codes. Both conservatives, who naturally distrusted government oversight, and even some Progressives felt that big government was going too far. Justice Brandeis voiced concern about the risk of increased centralization, statism, and big government control.14

The NRA soon collapsed, ending intensive oversight of companies, but the federal government nevertheless assumed greater regulatory and administrative authority over markets. The Communications Act of 1934 set up the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to oversee the airwaves. The Robinson‐Patman Act of 1936 extended the FTC's purview to protecting smaller businesses from “unfair” competition – such as A&P's pricing arrangements (see Chapter 2).15 The Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938 launched the predecessor to the Federal Aviation Administration, while the Agricultural Adjustment Act stabilized prices for the benefit of both large corporations as well as family farms. Despite the Schechter Poultry decision, the executive branch now wielded strong powers overall to regulate corporations.16

That oversight extended to corporate finance. Bolstered by policymakers such as Adolph Berle, the new Securities and Exchange Commission worked to protect dispersed shareholders, a linchpin of what would develop into American shareholder capitalism decades later. Congress also passed the Glass‐Steagall Act in 1933, which furthered the American tradition of decentralized finance by separating banking from investing.

If business leaders reluctantly accepted government management during the Great Depression, the benefits of public‐private partnership grew more positive with America's entry into World War II – at least for big companies. Enlisted by the president to turn the nation into an “Arsenal of Democracy,” incumbents converted factories to support the war effort and reaped most of the massive federal spending that resulted.17 Half of all government spending went to 33 companies.18 America's war production effort proved more effective than those of Germany, Japan, and Italy, as well as the allies. The successful Manhattan Project inspired a great many subsequent corporate and government development efforts, particularly in the area of science.

Big Science and Corporate Conglomerates

The post–World War II period initially seemed to confirm the new big business consensus. Large firms converted back to civilian production so quickly that the postwar dip was brief and mild. John Kenneth Galbraith, the prominent economist and a wartime price control administrator, published American Capitalism in 1952, arguing in support of large firms but also for “countervailing powers” such as big labor and big government to keep them in check. Big companies were henceforth to be disciplined not so much by upstarts as by equally powerful governments, labor unions, and other institutions.19 Fueled by pent‐up demand, European reconstruction, and the war's technological advances, the American economy began a long boom.20 The government entered the R&D business, setting national priorities that suited its purposes but that also resulted in numerous commercial spin‐offs. Scientific advances turned into practical goods. Federal and state governments helped to staff those labs with the GI Bill and heavily subsidized universities.21

While a few of the biggest companies engaged in fundamental research, most of them relied on public‐private partnerships. The federal Office of Scientific Research and Development supported a host of technology initiatives. Vannevar Bush, its storied director, exemplified the close ties and the government's handmaiden role with innovation. A cofounder of Raytheon as well as a professor at MIT, he believed that central direction and investment were necessary to speed up the exciting technological development then unfolding. Frederick Terman at Stanford University adopted a similar alliance on the West Coast, helping to create what is now known as Silicon Valley.

The cozy business‐government relationship and the imperative of scale often made it hard for disruptive companies to enter markets. Oligarchies dominated wide sectors of the economy, including steel, automobile manufacturing, aviation, radio and television broadcasting, and many consumer goods. From 1947 to 1968, the “Age of Oligopoly,” the share of manufacturing handled by the 200 largest industrials rose from 30% to 41%, and their share of total incorporated production assets rose from 47% to 61%. A tighter group of 126 firms conducted three‐quarters of all corporate research and development.22

Resisting the Lure of Central Planning

While the federal government played an important role in coordinating the economy, it nevertheless avoided the central planning or tight oversight of industry adopted by other countries after the war. Germany and Japan, bolstered by the Marshall Plan and other U.S. support, relied on overt industrial policy to rebuild their economies. In Japan, for instance, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) helped to lead consortiums to resurrect and resuscitate new firms and industries. Several European countries, including Britain, France, and Italy, accommodated labor parties and moved to “socialist lite” models by nationalizing infrastructure‐oriented industries such as banking and railroads.23

More menacingly, the communist states of China and the Soviet Union embarked on central state control. But while the Soviets made notable progress in areas such as science, particularly space exploration, its domestic production languished and consumers struggled. In China, Mao's central planning left the economy in shambles, with mass starvation. By 1968, the need for markets was apparent to virtually everyone within and outside those systems.24

While the U.S. government relied on intervention and oversight rather than outright control, it still took an active role in economic affairs. For instance, rather than force companies to provide health care or put workers on their boards, the government relied on private negotiations between companies and labor to recalibrate relations and secure benefits.25 Congress also passed the Celler‐Kefauver Act (1950) in order to close loopholes in the Clayton Act and discourage firms from acquiring direct rivals, suppliers, or distributors. The act limited vertical integration, which had allowed large corporations to erect barriers to entry in many markets.

The DOJ and FTC also became more aggressive in enforcement, with more than 2,000 antitrust suits brought in the 1950s. In some industries, the government worked to foster multiple suppliers, which created new enterprises of scale. Policymakers took pains to preserve the possibilities of entrepreneurship, or at least competition, forcing companies with large patent pools to license them and encouraging multiple competitors in key industries such as defense.26 Similarly, the federal government challenged DuPont's acquisition of a 23% interest in General Motors in the late 1950s in order to limit the ability of the former to control the automaker. Officials may have gone too far in limiting some vertical mergers, such as when the Supreme Court backed the DOJ in the Brown Shoe Company v. United States case (1962) – prohibiting a relatively modest acquisition because it might lessen competition.

Checked from buttressing their incumbencies through horizontal or vertical acquisitions, many of the “entrepreneurs” of this era were ambitious corporate leaders who pursued new ways to deploy capital made inexpensive from postwar savings. Sensing the financial advantages of holding a diverse portfolio of industries, they assembled conglomerates of unrelated businesses. Gulf & Western (originally an automobile parts supplier) and International Telephone and Telegraph were particularly prominent. By 1970 more than three‐quarters of the Fortune 500 had diversified.27

Management consultants supported this move, with the “growth share matrix” and “experience curve” explaining the benefits of portfolio management.28 At the same time, some like Peter Drucker were seeing the risks of bloated companies.29 Financial companies helped by gradually enticing investors back into stocks after the devastating losses of the 1930s, keeping capital costs low. The commercial paper market advanced, giving companies more options for short‐term borrowing. But with stable revenue, big companies were increasingly comfortable reinvesting their earnings for growth.30

Even in this era of bigness, entrepreneurial activity continued in new areas, often related to infrastructure, demographic changes, or emerging technology. The postwar car boom, literally paved by the federal government with the interstate highway system, opened cities to suburbs and freed travelers from the constraints of train routes and timetables. The trucking industry grew significantly. Besides dethroning the original big business, railroads, these changes accelerated growth in the broad consumer market and fueled upstarts in industries from hotels (Howard Johnson's) and restaurants (McDonalds) to retailing (Walmart). Increased air travel, new appliances, suburban housing, and television opened other opportunities. Franchising helped some entrepreneurs rapidly scale up national brands with local flavor.

Some opportunities were so vast that they attracted both incumbents and upstarts, often in a kind of symbiosis. Military contracts spawned the computer industry, instilling in the early firms a culture of hierarchical, secretive research and development. While incumbents such as IBM and Raytheon prospered, so too did Route 128 upstarts Digital Equipment Corporation and Data General.31 Innovation proceeded apace, in hardware and software, with help from the emergent venture capital industry.32

An Entrepreneur for the Age of Bigness

Only in the new era of big business could someone like David Sarnoff be an upstart. He was nine years old when his family immigrated to New York from Russia in 1900, and by age 15 he was working fulltime to support them. He was fortunate enough to get a job as office boy at the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, the high‐tech leader of its day.

Then in 1919, after World War I, in the interests of national security, the federal government wanted to use size to speed up the development of radio. Troubled that the key patents were owned by multiple companies – General Electric, Westinghouse, and AT&T as well as Marconi – it forced these companies to set up a patent pool. GE soon bought Marconi outright, then collected the patents in a subsidiary co‐owned by the other patentees. GE called its new subsidiary the Radio Corporation of America, and the hard‐driving Sarnoff was by then its commercial manager.

Sarnoff was a visionary who the saw the possibilities for broadcasting to masses of people. His bosses ignored his memos – until he arranged radio coverage of a major boxing match in 1921 that proved a success. Sales of home radio receivers took off, and in 1925 RCA launched the National Broadcasting Company to send programs to radio stations. Sarnoff led the push to standardize radio broadcasting around RCA's preferred format, and he signed recording contracts to ensure plenty of content while controlling the distribution of radio spectrum. Soon every household wanted a radio set.

By the late 1920s, as NBC was expanding its fledgling network, rival networks emerged and the federal government in 1932 forced GE to spin off RCA as an independent company so others could use its technology. Sarnoff, by then RCA's president, promptly pushed research in the next big thing, television, first broadcast in 1939. He again ensured that RCA's format would become the standard, and the company prospered in both the hardware of home receivers and the content of broadcasting through advertising. He won the next battle too, a tough fight with CBS over standards in color TV. And he did all of this despite knowing that television would likely cannibalize revenue from radio, which gradually declined.

Sarnoff thus benefitted from the federal government's de facto industrial policy: select a leading company and give it special privileges (mostly antitrust exemptions) to hasten development in a strategic area. In the post‐Progressive period of 1920 to 1980, officials believed that managers of large organizations in capital‐intensive industries would better carry out entrepreneurship than upstarts in small firms. But even as the federal government “picked winners,” it limited those protections to foster competition over time.

Even with this support, like most incumbents, RCA eventually lost its way. In the 1970s, rather than compete with lower‐cost foreign manufacturers, it diversified beyond consumer electronics. Efforts to enter the computer industry failed. In 1986, ironically, GE reacquired the company while selling off most of its assets.

The Great Dismantling

For all its apparent success, the bias for bigness came to halt in the 1970s. The end of the postwar economic boom broke the spell cast in World War II. Executives suddenly had to worry about factors they hadn't faced in a generation. Oil supply shocks and rising foreign competition took their toll, both economically and culturally. Slowing growth and stagflation undermined the prestige of large corporations. The 1970 bankruptcy of the Penn Central railroad, one of the 10 largest companies in the country, broadcast the pitfalls of bloated bureaucracy, overdiversification, and government regulation.

Large incumbents found themselves on the defensive. For conservatives, the Cold War fight against Soviet central planning favored markets over oligopoly and industrial policy, while libertarian thinkers centered at the University of Chicago blamed cozy business‐government relationships and “regulatory capture” for the lost international competitiveness. Economists argued that consumers would benefit from greater competition even if that reduced the efficiency of large firms. Legal theorists questioned the effectiveness of antitrust as a policy tool. Business scholars claimed that large corporate bureaucracies were now less about efficient coordination and more about managerial fiefdoms.

Liberals distrusted big institutions of any type, while postwar affluence was creating a new generation concerned more with individual expression than organizing around a common goal. The disastrous Vietnam War, followed soon after by Watergate, cast doubt on experts leading any large organization, public or private. The consumer protection movement, led by Ralph Nader, challenged not just big manufacturers but the FTC as well. Meanwhile the Supreme Court gave corporations more freedom from regulation, recognizing commercial speech in overturning local restrictions on advertising.33

The malaise made itself felt among incumbents throughout the industrial economy, but perhaps most acutely in the centerpiece of the American economy: automobiles. Their nemesis was not so much Nader as it was the Japanese car industry, built up in the 1950s and now eager to sell overseas. Suffering from an initial reputation for shoddy cars, they made a virtue out of necessity and built low‐cost, small, and fuel‐efficient vehicles – a low‐margin segment that Detroit automakers largely ignored. When the oil shocks of the 1970s encouraged Americans to try out the vehicles, they were impressed with their quality and dependability.34 As Toyota, Nissan, and Honda gained brand acceptance and expanded their U.S. operations, they moved into the more attractive and lucrative luxury segment – leaving an opening for Korean upstarts Kia and Hyundai in the 1990s.

Though some saw the success of Japan and Germany as justification for an aggressive national industrial agenda, most policymakers began to withdraw from the big business–big government consensus that had prevailed in the prior decades. Entrepreneurs benefitted in many fields, including government‐sponsored research. In the Bayh‐Dole Act of 1980, for instance, Congress aimed to distribute the ownership rights of federally funded research. Many universities encouraged professors to commercialize their findings, fueling a wave of start‐ups. And in response to concerns about overpricing at big pharmaceutical companies, the Hatch‐Waxman Act of 1984 permitted the manufacture of generic alternatives to branded drugs.

Even the regulatory regime, which managed bigness but ultimately protected it, needed overhaul. A wave of deregulation began in the Carter administration in the late 1970s. The transportation (railroads, trucks, and airlines), finance (retail brokerage commissions), and telecommunications industries were all freed to pursue opportunities, including competing headlong against rivals.35

The Reagan administration intensified those efforts after 1980 with a larger and deeper critique of big government (if not big business), and it unleashed a wave of activity. Books such as Robert Bork's The Antitrust Paradox, George Stigler's work on “regulatory capture,” and other “Chicago School” law and economics faculty led to officials emphasizing limited government and a focus on consumer interests more than competition between companies.

Antitrust enforcement diminished under Reagan, who had once been a spokesman for GE. Cases against AT&T and IBM, both commenced in the 1970s, had proved costly and largely unsuccessful. Reagan settled the AT&T dispute and dropped the IBM case on the same day in 1982. Policymakers, seeing how free markets generated efficiency, believed they could foster competition with less regulation, not more. Underlying this approach was the presumption that most markets were “contestable” – that new entrants would challenge incumbents and keep them in check, supplanting the need for most government action.36 This may have seemed like a specious rationale at the time, but the next several decades of entrepreneurship bore it out.

The new openness hurt conglomerates and sleepy incumbents the most. Companies that could not unlock their embedded value were pried open. Financial deregulation, which had actually begun back in the late 1960s, was showing results. By the 1980s, a field that had long been the comfortable preserve of a handful of venerable investing firms, most named for long‐dead founders, had opened to new challenges and challengers. Michael Milken's research showed that cautious investors had overstated the risk of default from low‐grade corporate debt, and by the mid‐1980s he had created a market for new securities. Insurers and savings banks put money into riskier high‐yield “junk” bonds that funded upstarts in industries such as telecommunications. Changes to the tax code favored capital gains, and investors raised their appetites for initial public offerings. In the area of corporate governance, economist Milton Friedman's argument that the role of the corporation was to make money for shareholders, academic research such as by Michael Jensen on the agency costs of the firm, and legal decisions such as the Revlon Rule in Delaware (requiring boards to maximize shareholder value), ushered in an era of hostile takeovers and shareholder activism.37

Beatrice Foods, for example, had faced declining profitability by the late 1970s, yet continued to diversity by adding rental cars, motor oil, and pantyhose into its already broad portfolio. By 1986, a new kind of upstart forced the company's hand. Kohlberg, Kravis & Roberts, one of the largest of the new corporate takeover artists, bought Beatrice in a leveraged buyout for $8.7 billion, the largest ever at the time. Over the next four years they sold off nearly all of its divisions, with the once‐central dairy business going to erstwhile rival ConAgra Foods.38 The new era of corporate raiders and management buyouts had begun.

Financial liberalization also expanded venture capital. While several venture firms had cropped up beginning in the 1950s, most of those firms were funded by wealthy families and had only a modest amount of money. That changed with modifications to the pension guidelines in the early 1970s, which enabled pension funds to invest in venture capital and riskier asset classes.39 The changes spurred the creation of investment firms dedicated to innovation – a major catalyst for the high technology industries that emerged in the 1990s.

The Cultural Shift

The movement away from large incumbents took on a decidedly cultural tone in the field of computers. The industry's anti‐authoritarian streak began on the West Coast in the mid‐1950s, when the “Traitorous Eight” left Shockley Semiconductor to found Fairchild Semiconductor, which in turn spawned numerous “Fairchildren,” including Intel. This legendary “mutiny” created Silicon Valley lore that only increased with the Beat Generation in the 1960s. Personal computing became a huge growth area, spawning not just innovative hardware and software but ultimately the blossoming of electronic commerce. It was also a crucial factor in enabling the locus of entrepreneurship to shift back from big corporate groups to small teams. With so many resources now available to individuals – no more waiting to share time on a costly mainframe – anyone with a good idea and some software or engineering chops could start a company

Large, hierarchical East Coast companies gave way to nimble West Coast upstarts.40 IBM, the very definition of an incumbent, had developed a personal computer in the late 1970s, but thought so little of it (or perhaps worried about antitrust threats) that it allowed a small Seattle software firm, Microsoft, to control the core intellectual property. Most of the East Coast firms, including one‐time upstarts that had quickly become incumbents, failed to adapt and went under. They had done much to foster new technologies, but their inability to focus on new opportunities, or their fear of disrupting their existing businesses, prevented them from following through.

Xerox had developed much of the key personal computing technology at its legendary Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), while Bell Labs created much of the internet's foundations. Yet these companies lacked the appetite for creative destruction and proved unable to commercialize these advances. While the success of the Manhattan Project was the shining light for corporate America in the 1950s, PARC's willingness to allow Steve Jobs to imitate the “mouse,” and IBM's ceding of its operating system to Bill Gates, became the next generation's proof text for the dangers of incumbency.41

America's Unique Corporate Dynamism

The speed and smoothness of this shift from bigness was truly remarkable. While most people celebrate entrepreneurs as the drivers of change, perhaps the more significant accomplishment was the overall social and political tolerance for failure. America's willingness to let large companies fail has been an essential part of its record of creative destruction.

Nowhere is the evidence of this dynamism stronger than in the indices of the country's largest companies. The Fortune 500 list, ranking the largest American companies by revenue, started in 1955, and roughly 2,100 companies appeared on the list in the first 60 years. But only 53 of the original 500 companies appeared continuously during that period and more than a third (769) showed up for just five or fewer years.42 Incumbency, even at the highest levels of the economy, has been hard to maintain.43

This dynamism became acute in the 1970s, and the narrower Fortune 100 list actually declined from 1955 to 1988 as a percentage of both GDP and overall market capitalization.44 Entrepreneurs played a major role in shifting the economy away from heavy industry. While many leading firms continued to dominate established markets, the manufacturing sector as a whole garnered a smaller share of the index.45 By the mid‐1970s, technology and other service sector firms were becoming a large part of the economy.46

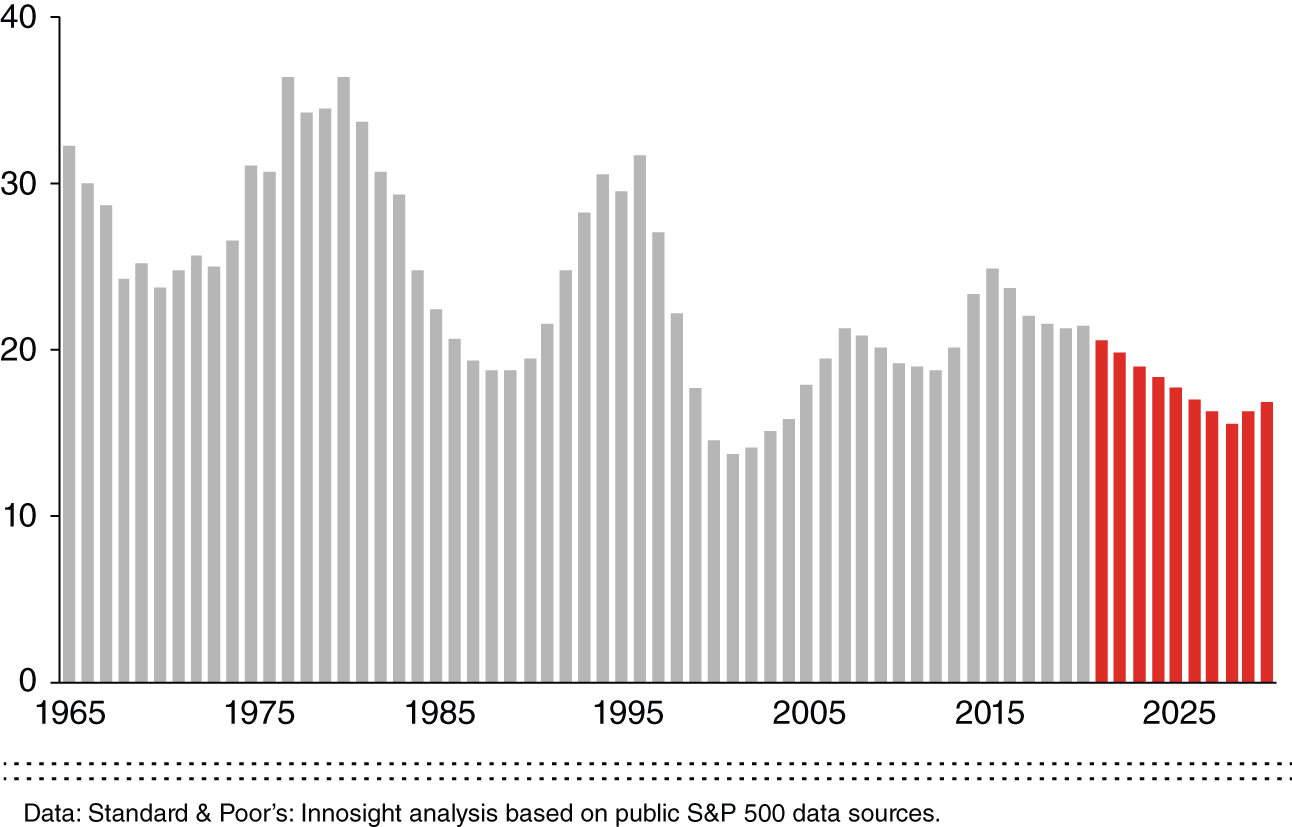

The churn rate has increased even more in recent decades. One assessment showed that the average tenure of a member of the Standard and Poor's 500 index shrank from 61 years in 1958 to 18 years by 2012. This study noted the relatively modest performance of those firms that did survive and the difficulty of merely incremental approaches to sustaining companies amid disruption.47 More recent studies have shown that the average tenure of top public company is now at an all‐time low, with the corporate lifespan on the index projected to decline to 12 years by 2027.48 (See Figure 7.1)

This turbulence is happening even as the largest companies have greater market capitalizations than ever. In 2000, General Electric was the largest firm on the S&P 500 index at $474 billion, and ExxonMobil was second at $302 billion. By 2018, Apple was in the top spot at $896 billion, and both GE and ExxonMobil had fallen off the top 10. While more than half of the companies on the 1995 list were no longer on it 20 years later, the list's overall share of U.S. GDP had actually doubled over its 60 years.49 Today, with several companies sporting market values in excess of $1 trillion, this trend continues.

Comparing the United States to other countries suggests that America has an edge when it comes to creative destruction, even if it brings with it increased social costs.50 While specific churn rates of comparable indices are difficult to find, most evidence suggests that industries in countries such as Japan, Germany, and Britain are much more static compared with the U.S.51 A large part of this can be explained both by culture and the protection of incumbent industries – either explicitly through regulation and industrial policy that favors certain “national champions” or implicitly through laws that protect the status quo or investors that are adverse to risk and innovation.

Figure 7.1 Average company lifespan on the S&P Index.

Source: Innosight 2021 Corporate Longevity Forecast, Chart 1.

In some countries, a pecking order of large firms and their networks of suppliers and distributors encourages loyalty and stability but results in few young firms reaching the upper echelons. Germany, for instance, is known for its stable hierarchy of businesses, including the Mittelstand medium‐sized companies that have been in place for long periods.52

One study of the FTSE 100, the London Stock Exchange index, found that an average of 10% of the companies listed on the index change every year. Of the 100 companies on the original list from 1984, only 24 remained in 2012. However, the study also noted that the typical age of the companies on the list is quite high, averaging over 90 years both 1984 and 2012.53 This is far older than the average age of major firms appearing on the comparable index in the United States, which is now less than 20 years.54

There are several countries with long lists of firms in existence for more than a century.55 The most striking example is Japan, where over 33,000 businesses are over a hundred years old. Shame associated with failure is one of the main reasons, and some argue that most managers are motivated to keep companies afloat, rather than to rejuvenate themselves.56 To many, excessive corporate longevity and the lack of creative destruction is becoming a problem.

Dazzled by the country's success in two world wars, in overcoming the Great Depression, in developing new consumer goods, and in fighting the Cold War, 20th‐century Americans put much of their trust in big business. In helping them rise to these challenges, the government intervened more aggressively in large firms than at any point prior, to some extent clipping smaller firms’ ability to stay competitive. Yet the country never entrenched the giant companies and it avoided the state‐controlled approaches of other countries. Similarly, it never abandoned its inherent belief in the right to compete. As a result, the major incumbents of midcentury failed to solidify their dominance through political and economic lock‐in. As they ossified into bureaucracies and failed to respond to foreign competition or economic stagnation, the political economy refused to come to their rescue. That left an opening for nimble upstarts with a fresh approach. The upstart‐incumbent balancing act thus proved more resilient than many experts would have expected. And when the need to liberalize arose toward the end of the century, American society pivoted back to competition and new upstarts positioned the economy for success.

By the end of the 1980s, the tide had clearly turned. At the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the rise of the personal computer revolution, deregulation of major industries, and the growing venture capital and high technologies were all underway. Moreover, a new generation – the Baby Boomers – were becoming prominent and powerful, and with them the next new breed of entrepreneurs. Large companies, or at least those that remained static, had their day, and the corporate life cycle could not be postponed forever – especially in the American system that never wholeheartedly embraced bigness, and that maintained openings for new rivals. A great age of upstarts was emerging.

Endnotes

- 1 Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power (New York: Free Press, 1991).

- 2 Joyce Appleby, The Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010), 324 (one million shareholders out of 6.5M shareholders in total; 76% of them earned less than $10,000/year).

- 3 Hush‐A‐Phone Corp v. United States (1956).

- 4 Federal Communications Commissions, Carterfone decision (13 F.C.C. 2d 420).

- 5 See Steve Coll, The Deal of the Century: The Breakup of AT&T (New York: Atheneum, 1986), and Tim Wu, The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires (New York: Atlantic Books, 2010).

- 6 United States v. United States Steel Corp. (1920).

- 7 John Landry, “Corporate Incentives for American Industry, 1900–1940,” PhD dissertation, Brown University, 1995.

- 8 John Steele Gordon, An Empire of Wealth: The Epic History of American Economic Power (New York: HarperCollins, 2005), 289.

- 9 Unfortunately, the war did not change some long‐standing racial animosities and barriers to entrepreneurship. In 1921, a mob of whites attacked a section of Tulsa with numerous thriving Black‐owned businesses. They burnt most of the structures to the ground and killed dozens if not hundreds of residents. But abetted by the local corrupt police force, none of the perpetrators were ever convicted. James Hirsch, Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race Massacre and Its Legacy (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2002).

- 10 Alan Greenspan and Adrian Wooldridge, Capitalism in America: An Economic History of the United States (New York: Penguin Press, 2018), 107–203 (automobiles went from 468,000 to 9M between 1910 and 1920; stock market capitalization grew from $15B to $30B; electricity, trucking, buses, factories all changed the landscape; the number of shareholder investors grew from 1M in 1900 to 7M in 1928).

- 11 Ellis W. Hawley, The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly: A Study in Economic Ambivalence (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966).

- 12 Many of the production codes, in fact, were established by industry incumbents. For instance, tire production levels were established by Goodyear, Goodrich, and Firestone. Greenspan and Wooldridge, Capitalism in America, 252.

- 13 See Matt Stoller, Goliath: The 100‐Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019), 209 (citing Richard Hofstadter, “American culture believes in entrepreneurial capitalism”).

- 14 See Stoller, Goliath, 125 (“tell FDR we are not going to let the government centralize everything”), and 123 (Brandeis's concern about link between corporatism and state power).

- 15 See Barry Lynn, Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), 50 (in favor of Robinson‐Patman and the Miller‐Tydings Act, which effectively overruled the Dr. Miles case). These price protections for small retailers are controversial as they limited discounting and cost consumers more. These acts were effectively repealed in the 1970s by the Consumer Goods Pricing Act, which gave large retailers more power to negotiate and set price, encouraging the success of big‐box retailers and lowering consumer prices. See also Stoller, Goliath, 63–87 (Wright Patman and “egalitarian system of free enterprise” vs. argument that consumer prices were much higher as a result), 204 (two‐thirds of Americans supported A&P over the government).

- 16 See Michael Lind, The Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United States (New York: HarperCollins, 2012), 250 (“Schechter was the last gasp of laissez‐faire”). See, e.g., NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp. (1937) and U.S. v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941) (upholding federal labor laws). States would also reestablish more power vis‐à‐vis corporations during the mid‐1930s. See, e.g., West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish (1937) (upholding state minimum wage laws and, in effect, reversing Lochner v. New York (1905) which had limited state regulations regarding bakers’ hours) and U.S. v. Carolene Products Co. (1938)(in footnote 4, the Court suggested a “rational basis test” and minimal scrutiny of economic regulations by the states or Congress, compared with strict scrutiny for cases involving political and other rights).

- 17 John Morton Blum, V Was for Victory: Politics and American Culture during World War II. (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1976).

- 18 Greenspan and Wooldridge, Capitalism in America, 268.

- 19 In fact, Galbraith and some others may have had disdain for entrepreneurs as a whole. See, e.g., Robert D. Atkinson and Michael Lind, Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2018), 7.

- 20 By the end of World War II, the country had 7% of the world's population but 42% of manufacturing output and produced 80% of all automobiles. The economy grew at a 3.8% annual growth rate between 1946 and 1973. Greenspan and Wooldridge, Capitalism in America, 274.

- 21 By 1956, there were 7.8M veterans in the workforce, including 450,000 engineers, 360,000 teachers, and 180,000 doctors. Greenspan and Wooldridge, Capitalism in America, 274; and Gordon, An Empire of Wealth, 364. See also David Hart, Forged Consensus: Science, Technology, and Economic Policy in the U.S., 1929–1953 (New Jersey: Princeton University Press).

- 22 Michael Lind, Land of Promise, 347.

- 23 See Appleby, The Relentless Revolution, 289 (post–World War II socialist bureaucracies in Great Britain, Italy, and France led to economies that were “government‐directed”; and nationalized railroads, banks and utilities; Soviet Union – “imperative”; U.S. – “informative” – private but some attempt to address inequality), 295 (“Continental Western European countries adopted a corporatist economic form. Government guided growth with fiscal and monetary policies, central banks virtually monopolized venture capital, and unions secured worker representation on corporate boards”), 297 (“Unlike American efforts to level the playing field through antitrust litigation, European countries tended to foster a front‐runner in its industrial sectors, thinking more in terms of industrial growth than internal competition.”).

- 24 See, e.g., Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest (New York: Penguin, 2011), 243 (discussing the “kitchen debate” and the role of consumer goods such as blue jeans and appliances in fighting the Cold War) and Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty (New York: Crown Business, 2012), 124 (the fall of the Soviet Union was due to an extractive political system, lack of economic incentives, resistance to change by elites, challenges of centrally planned economy, lack of technological change and zero‐sum rivalries at the top).

- 25 The “Treaty of Detroit,” concluded in 1950, secured health care and pension benefits for employees of the Big Three automakers, for example. The U.S. pushed companies to adopt strong programs for their employees but gave corporations and executives a “freer hand” compared with the welfare state of Europe or the managed economy governed by the Japan Ministry of International Trade and Industry. Greenspan and Wooldridge, Capitalism in America, 274, 288.

- 26 Lynn, Cornered, 165 (40,000–50,000 patents were covered under compulsory licensing arrangements).

- 27 Nitin Nohria, Davis Dyer, and Frederick Dalzell, Changing Fortunes: Remaking the Industrial Corporation (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2002), 64–65; G.F. Davis, K.A. Dieckmann, and C.H. Tinsley, “The Decline and Fall of the Conglomerate Firm in the 1980s: A Study in Deinstitutionalization of an Organizational Form,” American Sociological Review 59 (August 1994): 547–570.

- 28 See, e.g., Walter Kiechel III, Lords of Strategy: The Secret Intellectual History of the New Corporate World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 2010).

- 29 Peter Drucker cautioned companies to outsource as early as the late 1940s and to decentralize if they got too big. See, e.g, Peter Drucker, The Concept of the Corporation (New York: John Day, 1946).

- 30 On the development of corporate strategy and structure through the first half of the 20th century, see especially Alfred D. Chandler, Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of American Industrial Enterprise (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1969).

- 31 See, e.g., Edward B. Roberts, Entrepreneurs in High Technology: Lesson from MIT and Beyond (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); and Tracy Kidder, Soul of a New Machine (New York: Little, Brown and Co., 1981).

- 32 David Grayson Allen, Investment Management in Boston: A History (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015), 169–191.

- 33 Virginia State Pharmacy Board v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council (1976). See also Narain D. Batra, The First Freedoms and American's Culture of Innovation (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013).

- 34 David Halberstam, The Reckoning (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1986) and Maryann Keller, Rude Awakening: The Rise, Fall and Struggle for Recovery of General Motors (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1989).

- 35 See Thomas K. McCraw, Prophets of Regulation (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1984), chapter on Alfred Kahn.

- 36 Rudolph J. R. Peritz, Competition Policy in America: History, Rhetoric, Law (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2001), 260.

- 37 Revlon, Inc. v. McAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc. (Delaware, 1986).

- 38 Allowing ConAgra to buy Beatrice was itself a sign of the times. With heightened competition, regulators no longer worried about horizontal combination. George Baker, “Beatrice: A Study in the Creation and Destruction of Value,” Journal of Finance 47, no. 3 (July 1992): 1081–1119.

- 39 The changes to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act in the 1970s gave pension funds latitude to invest up to 10% of their assets in venture capital. See, e.g., Paul A. Gompers, “The Rise and Fall of Venture Capital,” Business and Economic History 23, no. 2 (Winter 1994): 1–26.

- 40 AnnaLee Saxenian, Regional Advantage (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996).

- 41 See, e.g., Michael A. Hiltzik, Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer Age (New York: Harper Business, 1999).

- 42 Alan Murray, “Myth‐Busting the Fortune 500,” Fortune, June 15, 2015.

- 43 Justin Fox “The Disruption Myth,” Atlantic, October 2014 (online reference to “What Does Fortune 500 Turnover Mean?” Dane Stangler and Sam Arbesman, Ewing Marlon Kauffman Foundation, June 2012). The authors identify sectorial change and greater efficiencies as causes of the churn.

- 44 Nohria, Dyer, and Dalzell, Changing Fortunes, 35–60. This study notes the shift from manufacturing to services and the variations by industry, with certain new industries growing (computers, electrical equipment, specialty chemicals, materials and defense contractors, and pharmaceuticals) while other industries were experiencing maturity and consolidation (metals, aerospace, food).

- 45 Thomas K. McCraw, Prophets of Regulation, 74–77, citing Alfred Chandler, The Visible Hand (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1977) and subsequent research (see list of the largest 200 manufacturing firms between 1917 and 1973). See also Innosight 2021 Corporate Longevity Forecast.

- 46 It should be noted that the list included only manufacturing firms until 1995, when services and other types of businesses were added. (In 1969, one‐third of the S&P 500 were industrial firms; by 2021 that number was 68).

- 47 Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan, Creative Destruction: Why Companies That Are Built to Last Underperform the Market and How to Successfully Transform Them (New York: Doubleday, 2001), 7–8, 11–13, 28–30 and Richard Foster, Innovation: The Attacker's Advantage (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986). But see Leslie Hannah and Neil Fligstein, who suggest churn is not a new phenomenon.

- 48 Innosight 2018 Corporate Longevity Forecast.

- 49 Alan Murray, “Myth‐Busting the Fortune 500,” Fortune, June 15, 2015.

- 50 Philippe Aghion, Celine Antonin, and Simon Bunel, The Power of Creative Destruction: Economic Upheaval and the Wealth of Nations (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2021).

- 51 Thomas K. McCraw, Creating Modern Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995). See also Aghion, Antonin, and Bunel, The Power of Creative Destruction, 239 (comparing France with the U.S.).

- 52 Peter Marsh, “Virtues and Foibles of Family Values,” Corporate Longevity, special report, Financial Times, November 10, 2015.

- 53 Rita McGrath, “Churn, Longevity the FTSE 100,” August 28, 2012. See also “Why Corporate Longevity Matters,” Credit Suisse Global Financial Strategies, April 16, 2014.

- 54 An alternative approach to comparing the United States with other countries can be found by looking at the longevity of family businesses across country. The Henokiens Association is comprised of family businesses that are over 200 years old. Today, there are only 47 members worldwide, with most of them in Europe (Italy, 12; France, 14; Japan, 4; Germany, 4; Switzerland, 3; Belgium, 2; England, 1; Austria, 1).

- 55 Foster and Kaplan, Creative Destruction, 291–293. See also Carlos Garcia Pons, “Business Longevity or the Business of Survival,” thenewbarcelonapost.com, February 27, 2018 (noting the UK's Tercentarians and Les Henokiens societies; Spain has 100 companies over 100 years old, Germany 800, France and The Netherlands, 200).

- 56 Bryan Lufkin, “Why so many of the world's oldest companies are in Japan,” BBC.com, February 12, 2020; Tsukasa Morikuni and Mio Tomita, “Corporate Japan struggles to scale up as longevity limits dynamism,” NikkeiAsia, November 8, 2018. See also Robin Harding, “Deep Roots in Need of Tonic: Japan's leader wants more companies to die and give way to start‐ups,” Corporate Longevity special report, Financial Times, November 10, 2015.