9

The Inflection Point?

After four decades of success, American entrepreneurial capitalism faced a critical challenge in the COVID outbreak that emerged early in 2020. At one level, the quick reaction to the crisis actually highlighted the strength of the nation's balanced economic system. The speedy vaccine development and rollout showed impressive collaboration between upstarts and incumbents, as new firms such as Moderna and established giants such as Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson all made important contributions. Retailers such as Target, CVS, and Walgreens led the mass distribution, alongside start‐ups that helped identify locations and schedule appointments. The strength of America's mixed economy was on display. The consensus around entrepreneurial capitalism, with its ability to enable innovation, create opportunity, and challenge large incumbent companies to stay sharp, remained largely intact. Moreover, the quick and strong stock market rebound and increased consumer savings as a result of government payments and other measures helped alleviate the crisis for many, at least temporarily.

Yet the crisis amplified long‐standing concerns over social issues that had bubbled below the surface for years. Some of these concerns had emerged with the fallout from the financial crisis in 2008 and the subsequent Occupy Wall Street movement. The divisiveness of President Trump, the George Floyd murder, continuing revelations from the MeToo movement, and intensified concern about climate change raised the tension markedly. The whipsaw effect of a near shutdown of the economy, followed just months later by a boom, labor shortages, and inflation, gave companies large and small as well as workers a topsy‐turvy ride. The election of Joe Biden as president also signaled a shift in economic policy, at least in antitrust. The American entrepreneurial system, it seemed, was arriving at an inflection point in which the entrepreneurial revolution might give way to the next big reset, including a rebalancing of the right to property and the right to compete and the role of government in mediating it.

Meanwhile the rest of the world is confronting similar choices. On the one hand, the fall of the Berlin Wall led to a consensus around capitalism as the superior economic model, and many countries are now trying to replicate American‐style innovation and entrepreneurship. Yet there also seems to be a global convergence around softening aspects of that system. How America navigates its way through this inflection point will be critical not only for its continued success but to maintaining its position as a model for other nations.

Social Concerns

The first and most important social issue is economic inequality. While the economy as a whole has grown significantly since the 1970s, the huge wealth created has not been shared equally; in fact, it became much more disparate. For the top 1% and even top 10%, particularly those who owned stock, the period was remarkable, with a sustained period of low interest rates rewarding holders of equities. For those at the very peak, such as technology titans, private equity and hedge fund partners, and corporate executives with hefty equity packages, it has been an extraordinary run. In the first two years of the coronavirus pandemic alone, America's billionaires added over $1 trillion to their collective net worth.1 Meanwhile over 20 million people lost their jobs and the real wages of most workers remained flat, with opportunity increasingly limited to those with college degrees, especially elite ones. Even with the “Great Resignation” that began in spring 2021 and the reset in employee relations that followed, there is a sense that the rich simply have a disproportionate share of – and perhaps just too much – money.2

Traditional opportunities seem to be drying up. Only a few years recovered from the financial crisis and under pressure from e‐commerce, small businesses suffered noticeably during the pandemic, as many customers stayed indoors and shopped online. Thousands of restaurant and hospitality firms were forced to close. And even when the situation eased temporarily between waves of COVID variants, worker shortages made it particularly difficult for smaller firms to compete on salaries and wages.

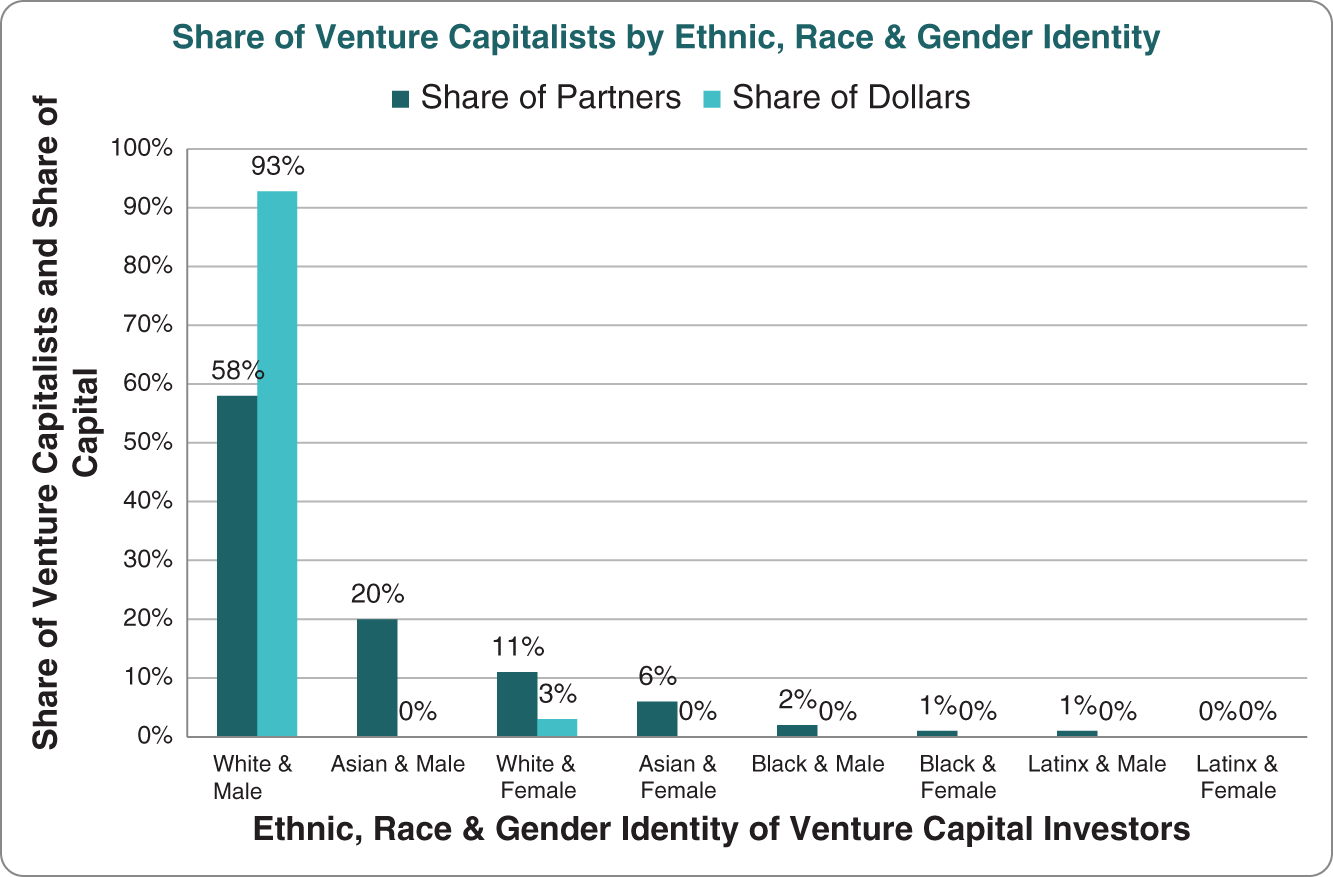

Along with inequality, lack of diversity and inclusion throughout the economy have come under scrutiny. Although laws, regulations, and corporate policies encouraged diversity and inclusion for decades with tangible results, many critics question the speed and extent of progress while noting uneven results in particular demographic segments. Female and minority participation in key executive positions, board representation, and other significant areas shows ample room for improvement. In the area of entrepreneurship, for instance, various studies have demonstrated that women and minorities receive far less venture funding and are also significantly underrepresented in the asset management firms that make investment decisions. (See Figure 9.1.) Beyond inequities involving class, race, and gender, the rewards are increasingly concentrated among a few groups, in a few cities, among people with degrees from a few select schools, though that is starting to change.3 And while American history has demonstrated openness to immigrants, industries like manufacturing and small business that had afforded opportunity in the past no longer fill that role.

Figure 9.1 Share of venture capitalists by race, ethnic, and gender identity.

Source: Courtesy of Elizabeth Edwards, H Venture Partners; Richard Kerby, Equal Ventures; and Knight Foundation/Knight Diversity of Asset Managers Research Series, December 7, 2021.

Finally, increased evidence of climate change is dramatically changing the way people think about companies and their responsibilities. This was already underway in the consumer market, where organic foods, sustainable brands, and recycled goods had been gaining in popularity for decades. But climate worries also sparked an overall challenge to corporate governance. The environmental, social, and governance (ESG) movement is pushing companies to do more in all of these areas, prompting management to confront social and political issues as part of their responsibilities. ExxonMobil, one of the largest firms in the world, lost a very public proxy contest on climate worries, waking up many to the possibilities for changing the way public companies might be governed. Institutional investors, both of their own accord and as result of pressure from their clients, supported this change; it was not a government mandate.

Challenging Big Tech and Revisiting Antitrust

The rising power of the technology giants has galvanized many critics, with some arguing that the past 40 years of hands‐off antitrust enforcement enabled vast concentrations of power in many industries. They point to dozens of industries in which big incumbents have consolidated and increased their market share and power. And even where consumer prices remained low, they argue, market access and entrepreneurship has been reduced.4

The focus on consumer welfare, rather than market share, as the barometer of competition policy has allowed incumbents to follow a two‐step path to market domination, say the critics. First a company invests in growth. It keeps prices low, innovates in product quality and accessibility, and wins customers away from rivals. It gains a dominant position in a market, but consumers are happy so regulators don't object. Then the company shifts strategy and works on monetizing its market position, including creating new products and services that squeeze out suppliers and vendors. Prices rise and overall investment falls. In a normal market, upstarts would enter to undercut the market leader. But it doesn't happen here because of the incumbents’ powerful position.

Once again, the tech giants have been the most prominent targets of criticism. The largest platforms of Facebook (Meta), Apple, Amazon, and Google (Alphabet), along with Microsoft, now dominate much of people's lives in areas such as media and e‐commerce, and these companies collect so much data on users that they have an additional competitive advantage over upstarts. The range of services they provide raises the switching costs, while network effects from large numbers of users enable the companies to extract huge rents from third parties while creating barriers to new entrants. As the tech giants continue to gather and mine data, ranging from consumer preferences and user history to emerging product and service needs, the advantage continues to compound. The imbalance is so great that, instead of competing head‐on, many upstarts now hope to simply to cash out to the incumbents for a hefty price. The continuing stream of upstarts may not be serious challengers but simply product development vehicles that can be absorbed into entrenched oligopolies as needed.

As with the natural monopolies of earlier eras, these critics call for supervision of Big Tech even though their competitive advantage is not directly a result of government privilege. Railroads, utilities, and even important patent pools were regulated or shared in prior periods, and some today claim we need a similar approach with the tech giants. After all, the now lightly regulated telecommunications companies are still closely watched.

Moreover, Microsoft's playbook from the 1990s remains a standard today: the other major platforms are also bundling offerings, quickly copying new features, and acquiring companies before they become threats. These incumbents argue that they are simply innovating or trying to stay current with competition or consumer taste, and that we need companies to stay nimble to compete in the global market. But both critics and some upstarts argue that the tech giants are essentially copying innovations and plucking off opportunities as soon as they ripen. As a result, they say, the incumbents are now not only preserving their dominant market positions, but also expanding in dangerous ways, far more than the industrial oligopolists of the early 20th century ever could. Facebook is influencing most of the media world. Google is leveraging its understanding of users to undercut advertisers and enter new businesses. Apple's closed marketplace is extracting hefty fees from app developers and content providers. Amazon controls an ever‐larger portion of consumer wallets and is using that position to undermine its suppliers. Information technology, the great engine of economic revival in the late 20th century, threatens to undermine our entrepreneurial dynamism in the 21st.5

The only solution, according to these critics, is stronger antitrust action at the federal level. They claim that digital technology has overwhelmed market forces, and that only government intervention can save consumers and preserve the public interest.6 Most of these critics call for dismembering or otherwise weakening the tech giants, such as by forcing them to spin off recent acquisitions or business units. And the Biden administration has listened, with many of the most prominent critics of Big Tech and large incumbents now heading antitrust enforcement.

Interestingly, much of the hostility toward Big Tech originates from incumbents both large and small in the same industries, under the theory that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Big‐box retailers such as Home Depot and Target are making strange bedfellows with Main Street small businesses in arguing against the power of the tech giants. Big telecommunications companies, traditional newspaper and media firms, and many other traditionally strong firms also claim to be disadvantaged. To some outside the fray, it appears that antitrust, to the extent it is active at all, has become an arena of contest among interest groups and countervailing powers. In fact, proposed legislation to curb tech platforms from offering competing products seems to ignore the fact that large retailers such as Costco and Target have been doing this for years, to the delight of consumers.7 Given the fluidity of industry definitions and range of interests, it is easy to see how consumer welfare became a standard that could cut through the complexity.

But this is starting to change. Given their size and power, Google, Amazon, and Facebook have each come under scrutiny for using their position and data to squeeze out rivals and limit new entrants, while Apple has faced a private action that argued many of the same principles. In its case against Google, the government alleged that the company was unfairly securing its position as the default search engine for computers and smartphones (including paying Apple $12 billion annually) and then using that position to increase leverage with digital advertisers. States also brought separate actions involving Google's use of its dominant position in the search field to parlay that into deeper engagement in specific categories, known as “vertical search.” A new DOJ case in 2021 explored its control over digital advertising technology.

A case in the District of Columbia claimed that Amazon used its position to pressure third parties to set prices, the first major antitrust case against the company in the United States. With respect to Apple, third‐party Epic Games argued that the AppStore ecosystem was too restrictive in requiring that all billing and enrollment take place within its marketplace. Finally, the case against Facebook related to its acquisition of “nascent” competitors, but the claim that its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp were part of a “buy and bury” scheme was hard to support. The government lost this case in 2021, but the FTC modified the complaint in a new attempt a few months later.

Amid these calls for government intervention, entrepreneurial capitalism continues to demonstrate a more direct and potentially more effective way of responding to Big Tech, best illustrated in the story of Marc Lore. A “baby‐buster” born in 1970, a math whiz from New Jersey, he had joined Credit Suisse's London office after college. He soon quit to start his own venture, “The Pit,” an eBay rival focused on collectibles. He sold out to Topps in 2001 and joined that company. Then in 2005, as a time‐starved new father annoyed with the hassle of getting supplies, he quit and cofounded 1‐800‐DIAPERS, later Diapers.com. The business grew rapidly with Lore's focus on membership‐driven discounting, using algorithms to find low‐cost suppliers. The success convinced him to expand to a portfolio of websites, called Quidsi, all catering to young families in urban areas.

Amazon noticed and offered to buy Quidsi in 2009, which Lore rejected. Spurned, it cut prices on diapers by 30%. Lacking the deep pockets to sustain a price war, Lore put Quidsi up for a sale a year later. Amazon beat out Walmart with $545 million bid, and Lore joined it as a high‐level executive.

He could have accepted the embrace of Big Tech incumbency, but he soon quit to scratch his entrepreneurial itch yet again. This time he aimed at a kind of Quidsi on steroids, which became Jet.com in 2014. With his Amazon proceeds as the foundation, he attracted more than a billion dollars for the venture. It aimed to be “the Costco of the internet,” with ever more sophisticated algorithms to reduce prices – unlike Amazon, which focused on convenience and cross‐selling.

Meanwhile Walmart's stores were losing out to fast‐growing Amazon, and its own online sales were sputtering. So it bought the two‐year‐old Jet in 2016 for a whopping $3.3 billion. Jet immediately became the center of Walmart's e‐commerce operations, with Lore as its hard‐driving head working to disrupt the incumbent.8 Once he had the operation in place, he quit in 2019 to form a new venture, a food tech upstart he called Wonder Group to disrupt emerging incumbents DoorDash and Uber Eats. And Walmart.com is now a viable competitor in e‐commerce, with its online sales growing faster than Amazon's.9

Lore's story counters the pessimism of antitrust critics who think entrepreneurs are helpless against tech giants. His success suggests that technology has enabled upstart competition just as much as it has undermined it. There is always room for innovation, speed, and fresh approaches. Despite two powerful incumbents in place, Lore found a way into the market and consumers responded favorably. And even when an innovator such as Lore sells out to a bigger firm, this assists in helping large firms to stay competitive. In fact, it is part of a virtuous cycle in which the strengths of both start‐ups and established firms can benefit.

Building on this story, there are several reasons why aggressive antitrust may be problematic or even undesirable. The first is that the targeted platforms deliver real value to consumers. As in the case of A&P a hundred years ago and many antitrust cases since, the objections to the Big Tech platforms are not coming from consumers, who continue to buy goods on Amazon, conduct searches on Google, and download apps from Apple at record numbers. Moreover, these firms have facilitated consumer trust and adoption of new services by standardizing important marketplace rules and easing important functions such as billing.

Second, there is a strong argument that these platforms actually help new companies reach the market much more quickly and with greater scale. Despite the argument that Big Tech firms use their position to copy ideas, most new start‐ups benefit greatly from being able to make their products known on Google, sold through Amazon or other e‐commerce marketplaces, or downloaded on an app store. And in some cases, the brand recognition they achieve may give them leverage over the platforms themselves over time, as Epic and Jet.com have demonstrated. Similarly, many new service providers can quickly launch through service marketplaces and even establish direct customer relationships as a result. Here, too, it is often incumbent retailers, media firms, or taxicab medallion owners that are pushing back.

Third, it is important that large firms be allowed or even encouraged to evolve. In the 1970s and ’80s, academics, corporate strategists, and policymakers worried about America's global competitiveness, fearing that companies did not move quickly enough; now, they seem to lament that corporations have become too nimble and too competitive. As noted in Chapter 2, companies have learned over the last several decades the importance of digital transformation and the need to be mindful of technology changes to survive, much less thrive. This is particularly the case when new technologies are developing quickly and venture capital is available.

Fourth, the major technology platforms themselves may be more vulnerable than many people first think.10 Facebook overtook Myspace and other companies, but TikTok has grown quickly and now rivals it for attention. Apple has faced pushback from third parties who bristle at some of its rules and restrictions, and it commands a smaller market share in software for mobile devices than Google's Android. Amazon has faced challenges in categories such as home goods and pet supplies, not to mention marketplaces such as Etsy and Shopify and the Marc Lore–rejuvenated Walmart.com. While the tech giants’ platforms look to lock in eyeballs, consumers may be more fickle than many critics imagine.11

Fifth, there is the issue of the corporate life cycle. Many great firms lose their energy when the founding entrepreneur leaves. A&P and U.S. Steel saw this happen, as did Apple when Steve Jobs left the company in 1985. Back in 2015, the New York Times reported that Jeff Bezos was creating a harsh work environment at Amazon. In meetings he would point in the direction of his Seattle corporate neighbor and tell managers he didn't want his organization to fall into Microsoft's complacency. He fretted that Amazon's success and market power would dull the organization to emerging threats. Boasting that the company's standards are “unreasonably high,” he has the company follow “purposeful Darwinism” with annual culling of staff.12 But this drive is extraordinarily hard to maintain, and it remains to be seen if the company can continue to operate at the same pace after Bezos's recent departure as chief executive.13

Even when entrepreneurs hand over the reins to able corporate executives, size and organizational dynamics can take a toll. Throughout American history, every company that became large eventually succumbed to stasis, complacency, infighting, and conservatism that rendered it incapable of keeping up with market trends. A glaring recent case is General Electric, which in the 1990s had seemingly reinvented itself for the 21st century. It was making all the right moves, transforming itself as a digital powerhouse, becoming the most valuable company at the height of the “New Economy” of 1999. But a mix of arrogance and insularity put it on the ropes by 2018.14 Even companies that continue to survive often break themselves up voluntarily to remain competitive. The great icon of Silicon Valley, Hewlett‐Packard, is a prime example.

Finally, antitrust and economic regulation are hard to get right. In an environment with lots of venture capital available and new technologies being developed constantly, even fast‐moving and well‐run companies that are on high alert for opportunities can find it hard to adapt, and this applies all the more so for governments, with political and special interests weighing in. While it is important to keep incumbents honest by peering over their shoulders from time to time, there are plenty of cases in which well‐intentioned government action has led to unintended consequences. Government action to force Kodak to open its service market contributed to the company's decline, even if failure to move quickly on digital photography was the main cause. Recent efforts to restrict book publishers from merging might actually help the tech platforms by limiting the potential for countervailing powers to develop.15

Good faith attempts to protect consumer privacy and control, such as recent European and California regulations requiring consent for the use of tracking cookies, can backfire; the regulations led to restrictions on “third‐party cookies” that hurt many small app providers.16 As one expert explains in his Laws of Disruption, lawyers, judges, and regulators need to be mindful of intervening quickly or aggressively, because “technology changes exponentially, but social, economic, and legal systems change incrementally.”17

Perhaps the greatest evidence of the ability of American entrepreneurial capitalism to reinvigorate itself is the continued rise in the number of unicorns, the success of countless smaller start‐ups, unrelenting expansion in venture capital, and the new innovations that come to market daily. In 2021, more than 5.4 million people in the United States filed an application to start a business, higher than even before the pandemic. All this is happening independent of the power of Big Tech, or even arguably as a consequence of them. And while there is merit in ensuring these giants do not overstep bounds, the inherent dynamism of an entrepreneurial economy, coupled with the virtue of a mixed economy that leverages both new upstarts and large incumbents, argues against aggressive antitrust or regulation. Such interventions risk impeding the economic successes that the country has witnessed over the past several decades.

Assessing European Capitalism and Regulation

For many critics of the American entrepreneurial economy, particularly those focused on social issues, the economic model prevailing in the European Union has broad appeal. Strong government administrative oversight in the E.U. has ensured more rights for workers, a stronger social safety net, and protections for small businesses. This model comes with expansive government, heavy regulation, and some government ownership of stocks and industry. Banks, workers, and governments have greater say over the corporation, sometimes referred to as “co‐determination,” including workers councils that limit layoffs or restrict innovation. There are also more assertive mandates for addressing climate change. European competition policy is often a misnomer, as noncompetition and protection are typically the actual goals. The grand bargain between interests has created an environment that tends toward stability and the status quo. The drawback, however, is difficulty for market entrants, less innovation, and higher consumer prices.18

Such drawbacks have attracted the attention of policymakers in Europe, many of whom have tried to liberalize their own laws to become more entrepreneurial. Emmanuel Macron of France is a prominent example, having publicly proclaimed a desire to open up the economy, though pushback from the “yellow vests” and challenges related to COVID have impeded progress toward that goal. Moreover, domestic politics continues to add roadblocks meant to deter innovators coming in from outside or disrupting traditional industries from within.19 Institutional investment in new ventures also lags.20 Even in Germany, the most productive economy in Europe, which has effectively managed liberalization along with coordinated government, feels pressure on its economic model. The ongoing move toward the knowledge economy is challenging the country's long‐standing institutional consensus.21 Meanwhile, the United Kingdom, which shares many of the features of the United States system, is also trying to increase its entrepreneurial ecosystem in the wake of Brexit.22

Because of these strong country‐by‐country interests, European entrepreneurs face a fragmented political marketplace. It takes them longer to access a large market and reach scale than in the United States, as illustrated by the difference between Uber and its European counterparts noted at the beginning of the book. While both the American and European competitors have fought to work through local regulations and political fallout on the Continent, Uber’s and Lyft's start in the larger and relatively open American market allowed them to more quickly gain scale, develop technologies, and raise capital, an advantage that European firms are still struggling to achieve.

The European Union was founded in part to create a common market, but it is only decades old, much younger than the political and institutional histories of the constituent countries. As described in earlier chapters, the American structures took many decades to develop. While the federal government assured the triumph of a single market, the balance between national and local interests continued throughout. Similarly, the right to compete and the ability to challenge the status quo took time, even as the strong constitutional system ensured that rights obtained in a dispute in one state would carry through to the others. In Europe, each country maintains more control over swaths of their economies, deterring many features of a common market and leading to fragmented enterprises in many industries.23

Nevertheless, two features of the European model have received particular attention in the United States. The first is the approach of the European Commission to Big Tech. Over the past few years alone, the commission has brought actions against Apple (regarding app store streaming services), Amazon (over unfair use of sales data to favor in‐house products over third parties), Google (alleging unfair use of advertising technology to the detriment of other advertisers and online publishers), and Facebook (involving use of advertising data to enhance its classified ads marketplace). The European Commission has also levied large fines on American digital companies. The commission has had a long history in fining Microsoft for alleged abuses involving its market dominance, while Google has had to pay large penalties for using its Android app to enhance its position in general search and for restricting third‐party websites from showing competing advertising.24 Other noteworthy actions have penalized Amazon (fined by the Italian government for favoring its own logistics service) and Facebook (for violating privacy rules). Similarly, regulations such as digital service taxes in certain countries and the European Union's proposed Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act seek to limit the power of Big Tech, even at the cost of discouraging innovation and deterring new entrants.25

The common feature of many of these actions appears to be an effort to limit disruption by primarily American digital firms of the European market, protecting large incumbents and small firms. Because apps and similar technologies are so easy to access, the new technology platforms have been able to cross geographic and political boundaries more readily than innovators from prior eras. In doing so they have upset the political and institutional compromises that protected the status quo relationships among the participants. Much of the European regulators’ attention has been focused on preserving and even protecting those compromises and their local industries, rather than in expanding the market, increasing innovation, and enabling competition or new upstarts. Yet this may be changing, as the number of domestic unicorns has been increasing.26 This trend may increase pressure to open up markets to competition.

European regulations involving data privacy are more promising and have encouraged critics of the American model, as these regulations tend to promote transparency and even consumer choice. For instance, the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) passed in 2016 have given consumers more control over their data. The act is similar to legislation in certain states, notably California, as well as several other countries. While the concept behind the regulations makes sense, they will need to be monitored to ensure that they achieve the desired objectives and do not result in unexpected outcomes, as noted earlier.27

The second area in which European governments are taking a more active role than their American counterparts is in managing climate change and social responsibility. The EU began its foray into corporate governance in 2013 and by 2020 had passed the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) to require disclosures regarding social and environmental measures, including penalties for noncompliance. This has been quickly followed by Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) for nonfinancial firms.28 These provisions are stronger and more assertive than those found in the United States, which remains focused on reporting and accountability to shareholders rather than “stakeholders” broadly. As a result of these disclosures, more executives are paying attention to climate change and in many cases compensation is in part tied to progress on those goals. In several countries, directors are even being held accountable for addressing sustainability as part of their fiduciary duties.29 Of course, many American companies also report on sustainability and corporate social responsibility, but such reports are voluntary and critics often view them skeptically as “greenwashing.”30

While disclosure and transparency are essential, the European approach of more assertive government involvement in corporate governance brings with it great risks both to entrepreneurship and innovation as well as to sustainability. As noted in earlier chapters, heavy direct political involvement frequently leads to the misallocation of resources, inefficient use of capital, and reduced global competitiveness.31 It can also make it more difficult for activist shareholders to push for change or hold management accountable.32 One can easily imagine initiatives in the boardroom leading to decisions that are geared simply to meeting measurements that may prove inappropriate, unable to gain traction in the market, or susceptible to regulatory capture or cronyism. Moreover, heavy mandates may discourage innovators or investors from finding new approaches that might be quite effective but are not within specific guidelines. They may also deter the adoption and spread of new technologies, result in less choice and lead to higher consumer prices.

By contrast, America's more bottom‐up and market‐based approach may be more effective in making change, with less risk of cronyism or bureaucracy. In particular, while shareholder activism is often messy and uneven, it forces competing views and broader debate on important topics. It also enables firms, including management, boards, and diverse shareholders, to mediate among competing interests and find company‐ and industry‐specific strategies to achieve sustainability goals. The United States also has a stronger tradition of securities class action litigation, an important enforcement mechanism related to shareholder activism.33 The dramatic increase in ESG among both individual and institutional investors suggests that investors may be able to drive both sustainability as well as economic performance and find the right way to balance objectives. The recent success of the activist firm Engine No. 1 in winning a proxy contest involving ExxonMobil, as well as BlackRock CEO Larry Fink's letters to clients around the mission of corporations, demonstrate that change can happen without top‐down mandates.34 Certainly, more disclosure helps, but attempting to address the problems exclusively or even primarily through government mandates will shortchange the potential for entrepreneurial solutions.

Understanding China and Authoritarian Capitalism

Just a few months before the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall, Chinese citizens gathered in Beijing's Tiananmen Square to protest against their autocratic government and to advocate for democratic reforms. The movement appeared as generational as the ones at the Brandenburg Gate. The outcome in the near term proved far different, however, as the Chinese government brutally suppressed the protests. Yet many of the forces that had fueled it remained and even accelerated in the following decades.

When Deng Xiaoping announced that “to get rich is glorious” in 1978, few would have anticipated how adeptly Chinese citizens would pursue that mission. Deng pushed hard for reforms that helped spur accountability and productivity and sought “capitalism with Chinese characters.” The township and village enterprise initiative in the mid‐1980s gave local towns and factories more latitude in managing facilities and operations. Deng's policy of “reform and opening,” and his lifting of the “bamboo curtain,” proved critical to the country's development, even if a strong authoritarian undercurrent remained.35 It was Deng, in fact, who authorized the crackdown in Tiananmen Square.

But even Deng would have been surprised by the explosion of entrepreneurial activity he helped to unleash. Between 1980 and 2020, the country's economy grew more than 10% annually. By 2021, the country had enabled more than 172 “unicorns,” as befitting what is now the world's second largest economy.36 The number of billionaires grew dramatically, and while poverty remains an issue in many parts of the country, the astounding rise of the middle class has created a stable base of consumers and educated workers likely to propel growth well into the future.

Nevertheless, authoritarianism dies hard. And just as America and other countries may be facing an inflection point, the events of 2021 suggest that a pullback of a different sort may be underway in China. Under paramount leader Xi Jinping, the country has recently been executing a remarkable redirection. Partly to cement his party's control over the country, Xi has reined in its high‐flying tech leaders and cracked down on the entrepreneurial enclave of Hong Kong.37 Instead of encouraging these would‐be role models and national champions, he has forced them to retreat from world capital markets – making it harder for them to achieve global network effects for their platforms. While Xi's focus on “common prosperity” and his “new development concept,” which includes efforts to reduce inequality and protect privacy, may appeal to some, many of the policies appear to be simply attempts at securing government control.38 To get rich may still be glorious, just not too rich.39

Didi's recent travails, discussed briefly at the outset of this book, question whether entrepreneurship and authoritarianism can coexist over the long term. While entrepreneurship is continuing at a torrid pace, the economy is still in relatively early stages of development. The issue keeps coming back to creative destruction. Economists have long pointed to the “middle‐income trap” as a risk many developed countries face. While countries ranging from Argentina to Japan have been able to jump‐start their economies through assertive state actions, success also makes it easy for cozy oligopolies to settle in. Political institutions and economic actors tend to converge. Entrepreneurship becomes difficult and innovators become discouraged or even fearful.40

Perhaps the most interesting question is whether and how entrepreneurship might ultimately change the political institutions in the country and drive reform over time. As one observer has noted, China has a long‐standing suspicion of entrepreneurship, viewing the economy as a “bird in a cage” that must be given room, but not released.41 But once the successes are tasted, the entrepreneurial spirit is hard to contain, and many experts have noted how wealth and economic development can help foster democracy.42

The historian Niall Ferguson has painted several plausible scenarios in which China loses its momentum. The first involves natural stagnation from declining economic and political competitiveness, perhaps triggered by the collapse of a bubble (the recent Evergrande real estate debacle could be a harbinger). A decline in entrepreneurship may be a component, as the detention of high‐profile executives such as Jack Ma and the crackdown on liberties in Hong Kong and elsewhere may scare off would‐be innovators. The second scenario involves social unrest brought about by inequality, though here that very crackdown on excessive entrepreneurship may stem the tide. The third scenario is political unrest from the rising middle classes demanding more participation and other reforms – though if successful this movement could reverse the trend to authoritarianism and reignite entrepreneurship. Finally, China's aggressive foreign policy may lead to coalitions among neighboring countries and Western nations that halt the expansion and discredit the government.43

Regardless of how these or other scenarios unfold, the development of the Chinese economy and political system will clearly continue to be an important backdrop for America over the next several decades. Whether China picks up its entrepreneurial momentum again or retrenches into its authoritarian model, America's best path forward will be to keep its own entrepreneurial engine humming with enhancements to address its shortcomings.

The Only Thing to Fear

The United States is largely in control of its own economic destiny. As the long history of entrepreneurship has demonstrated, the country's unique political, institutional, and cultural forces are well equipped to evolve to meet changing needs and opportunities as they emerge. Closely linked with the country's form of democratic government and highly responsive to consumer preferences, the system has proved resilient and responsive, if also contentious and messy at times.

This entrepreneurial spirit has been leveraged continually throughout the country's history, both to identify and seize new opportunities as well as to serve as a natural check on incumbency. Many of the social issues that need to be addressed today are likely to have entrepreneurially driven solutions tomorrow. Many underserved markets remain untapped, while a whole range of sustainable solutions are just finding their way into the marketplace. Similarly, the natural forces of “creative destruction,” spurred on by changes in demographics and consumer trends, paradigm shifts enabled by new technologies, and the natural limitations of large firms as they mature, will most likely limit power of now‐dominant companies in ways that government action cannot or should not, keeping the country competitive along the way.

As the examples of Europe, China, and indeed most other countries show, addressing these issues through assertive government action can lead to stagnation, cronyism, and even worse. The challenge we now face is how to build on the country's unique strength to ameliorate the social costs and ensure that the balance between upstarts and incumbents, large firms and small, and property and competition remain in place. During certain periods, the country has swung in one direction or another, sometimes favoring upstarts or incumbents, big government or small, property rights or the right to compete. Yet the system has always largely self‐corrected, thanks in large part to the open political arena. So long as policymakers understand the bounds of the system, and citizens‐consumers‐shareholders recognize when extremes are approaching, the system is well positioned to work through issues and remain strong in the years ahead.

Endnotes

- 1 Chase Peterson‐Withorn, “How Much Money America's Billionaires Have Made During the Covid‐19 Pandemic,” Forbes.com, April 30, 2021.

- 2 For useful context on how wealth has been viewed in America, see Robert F. Dalzell, The Good Rich and What They Cost Us: The Curious History of Wealth, Inequality, and American Democracy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), and Kevin Phillips, Wealth and Democracy: A Political History of the American Rich (New York: Penguin Random House, 2003).

- 3 See, e.g., “Beyond Silicon Valley: Coastal Dollars and Local Investors Accelerate Early‐Stage Startup Funding Across the U.S., Rise of the Rest,” Revolution.com/Rise of the Rest.

- 4 See, e.g., Barry Lynn, Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010), and Matt Stoller, Goliath: The 100‐Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019).

- 5 David Wessel, “Is Lack of Competition Strangling the U.S. Economy?” Harvard Business Review, March–April 2018; Tyler Cowen, The Complacent Class: The Self‐Defeating Quest for the American Dream (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2017).

- 6 Tim Wu, The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age (New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2018), and Lina Khan, “Amazon's Antitrust Paradox,” Yale Law Journal 126, no. 3 (January 2017): 564–907. See also Amy Klobuchar, Antitrust: Taking on Monopoly Power from the Gilded Age to the Digital Age (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021).

- 7 Michael R. Bloomberg, “A Bipartisan Bad Idea: Congress's attack on tech companies would hurt consumers, workers and the economy,” Bloomberg.com, January 28, 2022.

- 8 Ari Levy, “New Details on Amazon's Move to Shutter the Company It Bought for $545 million,” CNBC.com, April 3, 2017, https://www.cnbc.com/2017/04/03/amazon-was-sucking-in-quidsis-inventory-over-a-year-before-shutdown.html.“Who is Marc Lore?” Yosuccess.com, January 7, 2016, https://www.yosuccess.com/success-stories/marc-lore-jet/.

- 9 Richard Kestenbaum, “Walmart Is Gaining on Amazon in Ecommerce,” Forbes.com, October 20, 2021.

- 10 Jonathan Knee, The Platform Delusion: Who Wins and Who Loses in the Age of Tech Titans (New York: Penguin Random House, 2021).

- 11 See, e.g., “How Shopify Outfoxed Amazon to Be the Everywhere Store,” Bloomberg.com, December 25, 2021; Ashley Gold, “TikTok Surpassed Google as the Most Popular Site in 2021,” Axios.com, December 22, 2021.

- 12 Jodi Kantor and David Streitfeld, “Inside Amazon: Wrestling Big Ideas in a Bruising Workplace,” New York Times, August 15, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/16/technology/inside-amazon-wrestling-big-ideas-in-a-bruising-workplace.html.

- 13 Andrew Ross Sorkin, “Bezos Departure Letter,” Dealbook, April 16, 2021, and “Amazon After Bezos,” Dealbook, July 2, 2021.

- 14 See, e.g., Thomas Gryta and Ted Mann, Lights Out: Pride, Delusion and the Fall of General Electric (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020).

- 15 See Rudolph J.R. Peritz, Competition Policy in America: History, Rhetoric, Law (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 318; Eastman Kodak v. Image Technical Services (1992) (Kodak had 80–95% of the service market and the Court decided that the customer “lock‐in” was too strong). See also U.S. vs. Apple Inc., 952 F.Supp. 2d, (S.D.N.Y. 2013) (case against e‐book retailers, including Hachette and other major publishers); and Iain Murray, “DOJ's Case Against Publishers Is an Overreach,” November 24, 2021, Competitive Enterprise Institute (challenging merger of Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster).

- 16 Jessica Davies, “The Unintended Consequences of the shift from third‐party to first‐party cookies,” Digiday.com, September 26, 2019.

- 17 Larry Downes, The Laws of Disruption: Harnessing the New Forces That Govern Life and Business in the Digital Age (New York: Basic Books, 2009).

- 18 See William J. Baumol, Robert E. Litan, and Carl J. Schramm, Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism and the Economics of Growth and Prosperity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007), 188–227 (discussing “Eurosclerosis and Japanese Stagnation” and the Lisbon Agenda). See also Thomas K. McKraw, Creating Modern Capitalism: How Entrepreneurs, Companies, and Countries Triumphed in Three Industrial Revolutions (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998), 144 (noting the evolving role of the consumer in the U.S. compared with Europe).

- 19 Rebecca Rosman, “A new law in France aims to protect indie bookshops against outsized Amazon competition,” World, October 27, 2021 (new law in France regulates book delivery fees to help counter Amazon's competitive advantage). See also Angelique Christafis, “French MPs pass bill to curb Amazon's discounts on books,” Guardian, February 22, 2013, and Pascal‐Emmanuel Gobry, “The Failure of the French Elite,” WSJ.com, February 22, 2019.

- 20 Philippe Aghion, Céline Antonin, and Simon Bunel, The Power of Creative Destruction: Economic Upheaval and the Wealth of Nations (Cambridge MA: Belknap Press, 2021), 243 (U.S. has 84x the amount of investment by institutions going into young companies compared with France).

- 21 Sebastian Diessner, Nicolo Durazzi, David Hope, “Skill‐based liberalization: Germany's transition to the knowledge‐economy,” University of Edinburgh, April 13, 2021.

- 22 “Why Have We Not Grown Any Giant Companies? The U.K.'s Attempt to Take on Silicon Valley,” publicnews.in, September 23, 2021.

- 23 America also has more political change at the top than most European countries and certainly more than authoritarian countries such as China. This means less political monopoly and also higher stakes for regime changes in those countries. See, e.g., Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest (New York: Penguin, 2011), 47.

- 24 “Here are some of the largest fines dished out by the EU,” CNBC.com, June 27, 2017.

- 25 Alke Asen and Daniel Bunn, “What European OECD Countries Are Doing About Digital Services Taxes,” Tax Foundation, November 22, 2021.

- 26 “Europe has now created more unicorns than China” Sifted, August 20, 2021.

- 27 See also Joe Nocera, “How cookie bans backfired,” New York Times, January 29, 2022.

- 28 Cary Springfield, “What Is the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation?,” International Banker, April 13, 2021, https://internationalbanker.com/finance/what-is-the-sustainable-finance-disclosure-regulation/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20official%20wording,the%20provision%20of%20sustainability%E2%80%90related.

- 29 See, e.g., Financial Reporting Council U.K. Stewardship Code 2020 (more than 20 countries have signed on). See also “The Duty of UK Directors to Consider Relevant ESG Factors,” Debevoise & Plimpton Report, September 2019.

- 30 See, e.g., Alex Edman, “What Stakeholder Capitalism Can Learn from Milton Friedman,” ProMarket, September 10, 2020, and Lucian A. Bebchuk and Robert Tallerita, “Will Corporations Deliver Value to All Stakeholders?” Vanderbilt Law Review 75 (May 2022).

- 31 See, e.g., Mark Roe, Political Determinants of Corporate Governance (New York: Oxford University, 2006) (“politics can press managers to stabilize employment, to forego some profit‐maximizing risks with the firm, and to use capital in place rather than to downsize when markets are no longer aligned with the firms production capabilities”).

- 32 For example, several high‐profile boardroom battles in Japan and Italy show the challenges of making change at the corporate level in countries with traditions of fewer shareholder rights. See, e.g., Leo Lewis and Antoni Slodkowski, “Toshiba chief steps down abruptly,” Financial Times, March 1, 2022 (discussing the turmoil at Toshiba and the clash between corporate governance and shareholder capitalism), and “Ciao, salotto buono,” Economist, February 26, 2022 (discussing the struggle over governance at insurance company Generali).

- 33 See, e.g., John C. Coffee Jr., Entrepreneurial Litigation: Its Rise, Fall, and Future (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015).

- 34 See “Business Roundtable 2019 Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation” (signed by 128 companies). See also Andrew Ross Sorkin, “BlackRock Chief Pushes Big New Climate Goals for the Corporate World,” New York Times, January 26, 2021, and Adele Peters, “The inside story of how tiny hedge fund Engine No. 1 reshaped the Exxon's board,” Fast Company, June 10, 2021.

- 35 “To Get Rich Is Glorious: How Deng Xiaoping Set China on a Path to Rule the World,” The Conversation, July 9, 2021. See also Joyce Appleby, Relentless Revolution: A History of Capitalism (New York: W.W. Norton, 2010), 375–380; Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (New York: Crown Business, 2012); and Niall Ferguson, Civilization: The West and the Rest (New York: Penguin, 2011), 420–424, 437.

- 36 Tracxn, December 1, 2021.

- 37 George Calhoun, “What Really Happened to Jack Ma?” Forbes, June 24, 2021.

- 38 See, e.g., Li Yuan, “For China's Business Elites, Staying Out of Politics Is No Longer an Option,” New York Times, July 6, 2021 and Li Yuan, “What China Expects from Business: Total Surrender,” July 19, 2021.

- 39 See “China Economist Is Rare Voice of “Caution on ‘Common Prosperity,’” Bloomberg, September 1, 2021 (discussing the warnings of liberal economist Zhang Weiyang of Peking University).

- 40 Aghion, Antonin, and Bunel, The Power of Creative Destruction.

- 41 See, e.g., Richard McGregor, The Party: The Secret World of China's Communist Leaders (New York: Penguin, 2013) and Xi Jinping: The Backlash (New York: Penguin Specials, 2019)

- 42 See, e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson, Why Nations Fail, 443. See also Seymour Martin Lipset, “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy,” American Political Science Review 53, no. 1 (1959); Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics (New York: Doubleday & Co.,1960); and Marc F. Plattner, Larry Diamond, and Andrew Nathan, eds., “Will China Democratize?” China Review International 20, nos. 1–2 (2013): 145–150.

- 43 Niall Ferguson, Civilization, 319 (How Might China Stumble?), 422–424.