Chapter 15

Pathing Careers and Developing Leaders

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Grasping the importance of providing career paths for team members

Grasping the importance of providing career paths for team members

![]() Using mentoring and coaching to foster employee growth

Using mentoring and coaching to foster employee growth

![]() Increasing leadership skill in your organization

Increasing leadership skill in your organization

![]() Boosting your organization’s bench strength through succession planning

Boosting your organization’s bench strength through succession planning

![]() Developing employee recognition programs

Developing employee recognition programs

One of the chief responsibilities of your role as a people-focused leader is finding and recruiting the best people. But after they’re onboard, it’s every bit as important to help your staff keep growing professionally.

Companies that view ongoing leadership and career development as something employees should do on their own are missing valuable retention opportunities. Your team members — particularly your top performers — should be able to visualize their potential to advance and take on increasing responsibility within your organization. Employees clearly value this guidance from their organizations. Even before the Great Resignation and its challenges in keeping good talent, employees were waking up to the importance of career pathing.

LinkedIn’s 2018 Workplace Learning Report found that 94 percent of employees would stay longer at a company that invested in their career. The message is hard to miss: Employees want to know how to grow and advance with an organization. You can help them by creating career development programs that show them how they can translate their professional interests, preferences, and strengths into long-term careers with your organization.

Even though the umbrella for this chapter is on career development (supporting the advancement of team members and career growth), I focus this chapter on the specifics of career pathing and leadership development for good reason. Leadership development is about enhancing influencing skills and building leadership capability at all levels in the organization. Career pathing is the process of aligning organizational talent priorities with team member career growth. It’s driven by the team member’s interests, career aspirations, and skills.

Don’t get distracted by different terminology because it trips up many business leaders (talent management, talent development, career development, leadership development). The key is this: In order to get and keep great talent, you must have processes and programs in place to grow and develop them. This chapter focuses broadly on building leadership capability throughout the business over the long term and specifically highlights career pathing as a way to do that.

Understanding Why Career Development Matters

Today careers are often viewed as jungle gyms with multiple entry points, lateral moves, and a lot of options, versus the historical view of careers as ladders. Career development today encompasses moves in all directions with a focus on growth and impact. It’s an attitude that reflects the variety of opportunities all around. Instead of advancing upward, the encouragement for team members today is to embrace a more networked career in which they’re likely to move across, then up, then across again. The focus is not on the position title, but instead, the focus is on growth: developing skills and engaging in the right experiences aligned with individual career aspirations. Organizations should approach career development with this in mind.

This approach to career development is a win-win for the employee and the employer. Employees acquire know-how that benefits their careers both immediately and in the future. In the eyes of employees, this is no small advantage. A 2017 study by Glassdoor found that employees cared less about compensation and benefits packages and more about the company’s career development opportunities, culture and values, and the quality of senior leadership.

Although you may not be able to make promises to individuals about what the future holds for them at your business, you and the company’s line managers can work with employees to develop career maps that detail the steps required to achieve specific goals. An individual development plan (as I discuss in the previous chapter) can be a useful tool in this process. An IDP is a document that outlines the employee’s professional goals, as well as the steps the person must take to reach them. It allows you to consistently review, update, and discuss an employee’s developmental goals. When someone is ready for the next level but no position is available, an IDP can be used to identify growth opportunities within the existing position so the worker remains challenged and motivated.

Recognizing the Value in Career Pathing

As the workforce becomes more diverse, with employees coming from a variety of backgrounds, and fast-changing job roles and ways of working becoming more mainstream, it grows ever more challenging to ensure that employees have an understanding of career paths and how they can move forward.

Create a career roadmap.

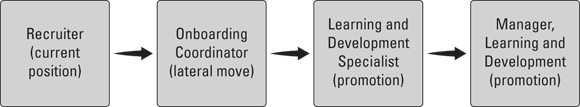

A career roadmap is a visual depiction of the vertical or horizontal position changes within any business function and is based on both the business goals and opportunities and team member aspirations. It shows the progression of growth over time. For example, a high potential team member in the HR/Talent function who is currently serving as a recruiter (but aspires to lead in the Learning and Development function), may have a career path that looks like Figure 15-1.

Create/leverage the position success profiles for each of the positions within the career roadmap.

Position success profiles outline the experience, skills, and competencies necessary for success at each position, so they provide critical guidance around necessary development within the career progression. Refer to Chapter 5 for more information.

Create a learning and development plan.

Based on the experience, skills, and competencies necessary for success in the next desired position within the career map, create an individual development plan (see Chapter 14) that outlines the specific development for the team member depending on their unique needs.

© John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

FIGURE 15-1: An example of a potential career path for a recruiter within an HR/Talent function.

Although the team member may have obvious benefits from career pathing, your organization also reaps benefits. It can help your organization sense where the skills and aspirations are in your workforce, which can benefit recruitment and succession planning.

Leveraging Mentoring as a Tool for Growth

Mentoring is often a development initiative used within career path (and other talent development initiatives) as a way to connect team members with necessary expertise to support their growth. The most valuable (and certainly the broadest) application of mentoring is its use in fostering overall leadership and career development for your staff. That differs from its other benefits in that it takes something of a longer view — an eye toward career development that can last a professional lifetime. That means using mentoring to build attributes that are effective today as well as farther down the road.

(Elsewhere in this book, I discuss the value of mentoring in specific situations. For instance, in Chapter 10, I examine how it can help new employees acclimate and become comfortable with your work environment. Additionally, in Chapter 14, I look at mentoring in the context of a talent development tool to help employees develop skills and know-how that benefit your business.) The following sections outline how to maximize mentoring relationships within your organization.

Why and how mentoring works

As I point out in Chapter 14, some skills and competencies, particularly soft skills such as communication skills, aren’t easily taught. Still, these abilities are pivotal to your staff’s ability to interact with customers and with each other in the office. Mentoring opportunities are ideally suited to this kind of skill and knowledge transfer.

One reason mentoring arrangements work is that topics discussed between mentor and mentee are typically kept confidential. If an employee is having difficulty working with some of their team members, for example, they can comfortably discuss these dynamics with a mentor in a way that’s not possible in a structured setting or with an immediate supervisor. This level of trust creates a psychologically safe environment that fosters growth.

Mentors can prove to be especially valuable resources as their mentees continue along their career development paths. For instance, a mentor can recommend ongoing learning opportunities that can best serve a mentee’s career goals. If a company position opens up that represents a form of career advancement, mentors can suggest effective strategies to pursue that opportunity — or why it may not be a suitable fit.

Here are some more ways mentors can assist in your company’s career development efforts:

- Helping to identify an employee’s long-term career goals: Many people — those in the early stages of their work life in particular — often fail to take the time to consider how they want their careers to progress over time and, for that matter, what that progress actually entails. A mentor can kick-start for an employee the process of beginning to think long term, not merely where they want to be next year.

- Acting as a dedicated role model: Instead of an employee having to reinvent the career wheel, a mentor can serve as a living, breathing example. The mentee can emulate the behaviors and attributes of someone who’s already taken a similar (and successful) career development path.

- Unlocking the power of networking: Career development doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Mentors can introduce their protégés to others who can prove to be invaluable points of contact and perhaps become additional role models.

Much like career development, which it supports, mentoring is a win-win activity. The relationship benefits not just the mentee and the company but also the mentor. In addition to bolstering their supervisory competency and leadership abilities, mentors gain the inner satisfaction of knowing that they’re facilitating someone’s career growth and assisting the company in cultivating a future leader. Helping employees work and interact more effectively also brings some concrete, practical career benefits to mentors. Serving in this role adds value to the organization and increases the mentor’s visibility and potential for advancement.

Setting clear expectations

Developing and implementing a mentoring program (whether informal or formal) takes more than the best of intentions. First, pinpoint your specific goals and make sure that they align with the organization’s goals and will benefit the employee in their current role. For example, you may want to increase retention rates, nurture employees who can help you introduce new product lines, or just make the onboarding process for new hires as stress-free as possible.

With those objectives in mind, consider what sort of mentoring arrangement may be most helpful. Do you want formal relationships — with partners in regularly scheduled contact — or do you want to operate more on an as-needed basis? Do you want to pair mentors with protégés in the same department or mix things up a bit? Also consider how the mentee’s manager will remain involved. There should be some type of communication process that helps all three parties (mentor, mentee, and mentee’s manager) stay engaged. Managers need to understand how they can help mentees in their day-to-day work.

Looking at the mentoring program as a whole, you need to decide who’s going to lead and champion it on an ongoing basis. Also, consider your budget and how you’ll measure the success of the overall effort.

Choosing the right partners — how to match mentors and mentees

The key to an effective mentoring program is to choose mentors who are temperamentally suited to the task. They don’t necessarily need to be your most senior leaders. Mentors should, however, be naturally empathetic and enjoy the role of helping, connecting with, listening, and sharing information with others.

Among other attributes, ideal mentors should have

- Excellent communication and leadership skills

- Enthusiasm for working together as a team

- Patience and understanding, particularly with less-experienced protégés

- Solid connections within the organization

- A sense of how much involvement with a protégé is appropriate and what crosses the line to micromanaging

- Credibility as a role model for your culture and values

- Get recommendations. Ask managers to recommend leaders within their teams who have the personality to act as effective mentors. Make sure that whoever they recommend has the time and capacity to devote to the task.

- Choose good role models. Select as mentors those whose attitudes you’d ideally want the new employee to emulate — for example, flexible, agile, open minded, enthusiastic.

- Talk to managers who have expressed that they’re nearing retirement or the next phase in their career. Sometimes people nearing retirement look for someone to mentor. This isn’t always the case, of course, but it may be worth checking out.

- Find common ground. As you narrow down relationships to specific individuals, look for things (same schools, similar hobbies, past experience in certain industries) that can create a rapport between mentor and employee.

Although there isn’t an exact science to matching mentors and mentees, consider these factors and two specific ways to identify pairs:

- Self-matching (mentees choose): With self-matching, individual mentees choose the mentor they would like to work with typically from a pool of mentors. This approach creates a lot of ownership and empowerment but can be challenging if multiple mentees choose the same mentor.

- Program administrator matching: With this common form of mentor matching, program managers choose the mentor-mentee match based on a set of determined criteria (skills, background, goals, and such). This allows the organization to be strategic in determining which mentors and mentees work together.

Not all matches work out, and if one doesn’t, it’s important to address it quickly. Ask for feedback from both the mentor and mentee so you can understand each of their perspectives. This insight can be helpful for improving how you manage the matching process in the future. It’s also important to quickly find a new match for both the mentor and mentee based on what they share with you. Work to help them have a positive mentorship experience.

Implementing mentoring (formal or informal)

A best practice is to provide an introductory training session for the mentors and mentees — it’s ideal to bring them together for this conversation. Even the most experienced employees will get a better handle on their mentoring responsibilities with some focused direction, and mentees will be set up for success. For example, both mentors and mentees can benefit from understanding the distinction between mentoring and managing and mentoring and coaching. They also need to understand what is expected of them and what they can expect from the experience. During this meeting, everyone can get on the same page regarding goals, expectations, and other elements of the program. Cover what’s required of everyone involved and how they can benefit most from the arrangement. Address meeting frequency, goals, and how long the program will last. Solicit questions from participants to be sure that no one is left in the dark on any critical issues.

Creating a Coaching Culture to Support Ongoing Career Development

Professional coaching has been widely used as a developmental tool for executives for decades, but more recently, there has been an explosion in expanding coaching access to individuals in all stages of their careers. The impact of coaching is clear, and organizations are realizing the value of coaching at all levels to support team member growth.

Before I share the specifics of how to use coaching to develop team members, I want to distinguish between the terms “mentoring” and “coaching.” The terms are often used interchangeably, but they don’t describe the same type of working relationship. Both share specific goals, including employee learning and career development that leads to peak performance, and the realization of full potential. However, the focus, role, and approach of mentoring and coaching are different. Table 15-1 compares the two.

TABLE 15-1 Comparing Coaching and Mentoring

Coaching | Mentoring | |

|---|---|---|

Focus | Coaching focuses on improving a specific skill or competency in a focused time period. | Mentoring focuses on building a two-way, mutually beneficial relationship for long-term career growth. |

Role | Identifying the gap between the current and desired state and helping the team member develop an action plan. The emphasis is on the team member finding the solution, not instructing or advising them. | The emphasis is on active listening, sharing specific examples in the mentor’s area of expertise, making suggestions, providing guidance, and making suggestions. |

Process | A structured process to help a team member accomplish a specific goal; the agenda is more specific, for a short period of time, and oriented toward certain results. | A mentee-driven process with less structure that allows for multiple areas of focus and growth over a longer period of time. |

Although many organizations leverage external coaches to support the development of team members, the best way to create a culture of coaching and use coaching as a career development tool is to equip leaders with coaching skills. Using leaders as coaches is an effective way to use talent to build talent.

Employee coaching is simply supporting team members to reach a goal. Your organization can utilize it to help an employee improve an existing skill set or expand into a new one, depending on the organization’s requirements. Just as coaching differs from mentoring, coaching also differs from a performance review or manager check-ins because it’s ongoing, in-depth support. A coach does the following:

- Provides positive feedback to encourage employee growth

- Discusses the goal or challenge openly

- Discusses solutions, approaches, or milestones

- Establishes a plan for achieving the desired outcome

- Sets a time and date to follow up

- Adjusts as necessary until the employee reaches the goal

It’s essential for the coach to refrain from giving the employee all the answers; the coach’s role is to provide space and guidance for the employee to find those answers themselves.

Using the GROW Model to Support Employee Coaching

A model that is commonly used by leaders to coach team members is the GROW model. GROW is an acronym that stands for Goal-Reality-Options-Way Forward. It’s an easy-to-use tool to support leaders at all levels in coaching team members to accomplish goals.

Think of the GROW model as a tool to help leaders lead a line of coaching questions. It helps to ensure that the coaching conversation is focused, natural, and future focused. Table 15-2 is a description and questions to ask for each part of the model.

TABLE 15-2 The GROW Model and Coaching

GROW | Description | Questions |

|---|---|---|

Goal | Clarifies what the team member wants or where they want to go. | What do you want to have change in this situation? What’s one thing you want to change? What’s your vision for what it looks like? What do you want from this situation? |

Reality | Establishes the current state. | Where are you now? How are you feeling? What’s getting in the way? What are the issues or challenges? |

Options | Explores options and discovers possibilities. | What might work best? What can you do now? What would it look like? How has this worked in the past? |

Way Forward | Sets the path forward. | What is the next best step? What is the most important thing to do now? What are the consequences of not addressing this issue? What will you do, by when? |

Building Leadership Capability Across the Business

Leadership development is a natural subset of career development. Leadership is influence, so by definition, all of your team members are leaders. The challenges, priorities, and values are different at different levels of leadership, but there is influence across the board.

Like career development itself, identifying and nurturing leaders at all levels can prove central to your business’s success — and its future (as I discuss in “The Future Is Now: Succession Planning,” later in this chapter).

Following is a common framework for distinguishing different levels of leadership within an organization (levels will vary based on the size and type of organization):

- Individual contributors are focused on a specific role or task. They lead from the seat by influencing key stakeholders and colleagues. They are also responsible for leading up, the process of providing feedback and insight to their manager.

Managers have a major role to play in employee career growth, not just in terms of team member career pathing and development but also in understanding individual employees’ personal strengths and development areas and providing a supportive sounding board for career growth ideas.

The transition from individual contributor to manager is an important one that’s often overlooked. Research from The Ken Blanchard Companies shows that 60 percent of all new managers fail or underperform in their first two years in the new role because they aren’t appropriately equipped to manage people. Getting results through others is very different from getting results on your own, and it requires a different set of competencies in order to be successful. This is precisely why it is mission critical to equip new managers with basic people leadership skills.

- Directors are leading managers, so at this level of leadership, the focus is setting leaders up for success. Key competencies include coaching and problem-solving to eliminate obstacles and empower managers to get results through their teams.

- Executive leaders are responsible for leading the business. At this level of leadership, the perspective is much broader on all aspects of the business. It’s a strategic focus that includes much time spent on external factors and growing the business as a whole.

Note that the focus and priorities vary by leadership level — it’s not a one-size-fits-all, so development efforts shouldn’t be one-size-fits-all either. How leaders spend their time varies at each level, as well as the values they implore. While there are certainly “people leader” competencies that apply across managers, directors, and executives, there are also specific competencies that support growth at each level — these specific competencies are the focus of any targeted leadership program by level.

Defining leadership qualities that will move your business forward

Being (or developing) a great leader at any level is not a simple proposition. Every business is unique, so a leader who’s effective in one setting may prove utterly ineffective in another.

For instance, if your business is more inclusive by nature, a leader who invites input and consensus would be a very suitable fit. Similarly, the top qualities of a leader in your sales group may be charisma and an eagerness to engage with others.

Integrity: The last thing you want are people who may lead others into actions that don’t reflect a commitment to being honest and forthright.

Your leaders set the tone for others within the organization.

Your leaders set the tone for others within the organization.- A knack for motivating others: The ability to spur others into action is a key sign of someone who can lead effectively.

- Ability to collaborate across groups and build consensus: A person who can’t convince people to work together isn’t much of a leader.

- Excellent communication skills: For leaders, communication is a must. Great communicators can adapt to their audience, are clear and concise, are diplomatic with requests, use straightforward language when talking and writing, are good listeners who seek to understand, and are always trying to improve their communication style. A 2018 report by Inc. found that companies with leaders who utilized effective communication skills produced a 47 percent higher return to shareholders in a five-year period.

- Adaptability: Leaders are willing to change as circumstances dictate and are comfortable with feedback — both positive and negative. This includes dealing with ambiguity, a critical skill for good leaders.

- Willingness to acknowledge shortcomings: The best leaders are willing to be vulnerable. They understand where their strengths lie and where they don’t (and are comfortable relying on others to fill those gaps in skill and experience).

A next step is to identify specific competencies necessary for success at each level of leadership within your business. Here are key questions to ask:

- What is the focus for leadership at this level?

- What are the key priorities?

- What are the values?

- What competencies are necessary for success at this level?

For example, a competency necessary for success at the executive level is strategic thinking, but this may not be necessary to lead at the manager level.

Determining your leadership development strategy: Factors to consider

To begin building a leadership development strategy, consider the following questions:

- Do you have or anticipate any leadership gaps? Consider what may be (or will be) missing within your organization in terms of leadership attributes and characteristics. In other words, what kind of traits does it take to keep your organization humming? One factor may be the retirement of long-term team members, which can cause a gap between middle-level and senior-level leaders. This may result in a shortage of leadership talent at the senior level in your business. Some companies create leadership tracks that address different leadership gaps, assigning executive-level sponsors with expertise in each area to help design, socialize, and champion each track. Tracks may include such areas as leading and motivating teams, clarity in communication, or business development.

- How does the program align to organizational goals and strategic objectives? How will leadership development assist your organization in meeting your goals? For instance, are you looking to grow financially, structurally, or in some other fashion? Sync your leadership development program to those priorities.

- Are you thinking long term? Be sure to address both short- and long-term goals. Too often, companies think about filling a particular role and overlook longer-term needs. Focus instead on developing a “bench” of talent versus grooming people for specific roles only.

Leadership development program options

Leadership development, mentoring, coaching, and succession planning are all linked. Most leadership development programs include some kind of mentoring, coaching, and organizational future planning. Individual activities can include one-on-one or group coaching, working with an assigned mentor, rotational assignments, job shadowing, project leadership, classroom learning (such as MBA programs, executive education, and online courses), and other options. External coaches and business school programs can be helpful (especially for larger organizations with commensurate budgets). There’s an extensive external market for leadership development firms to partner with — the best firms serve as partners to come alongside you and customize a leadership development program to improve the competencies most important for your business success.

Measuring progress and success

Because the focus of leadership development is on growth, it’s mission critical to build in measures throughout the program to gauge progress and measure growth. Here are some questions to help:

- Do participants feel they’re progressing? Ask people in the leadership program what they are gaining from the process. Do they feel they’re learning and growing? How are they putting what they’ve learned into practice?

- Are their leadership activities and responsibilities increasing? If so, how are they handling them? Do the people or departments they’re managing have higher levels of productivity, customer satisfaction, and so on?

- What do others say? Solicit feedback from employees who have worked with those in leadership programs. Do they feel the candidates are developing into effective leaders? If so, in what fashion? Taking employee comments in aggregate, try to measure leaders’ success in terms of retention and employee engagement within their respective teams. A 360-degree leadership assessment tool is a helpful way to gain valuable data (particularly at the beginning and end of the process).

- Are your development efforts positively affecting overall business goals? For instance, if one objective is to open additional branches, have beneficiaries of your leadership development efforts contributed to designing, implementing, or staffing new locations that are up and running?

- Is there a ripple effect? A strong leader will also develop other leaders. Are individuals in your program reaching out to develop further talent?

- Are you doing enough to keep the leaders you’re grooming? Don’t forget to develop and update incentives to keep candidates with the greatest leadership promise onboard. The last thing you want to happen is to invest time and resources in a promising individual, only to have that person jump ship because a more attractive opportunity surfaces elsewhere. Make sure that compensation and opportunity are sufficient to ward off advances from rival businesses. Consider creating a mentoring group to bring developing peers together from time to time so they can share experiences and progress toward their goals.

The Future Is Now: Succession Planning

In a way, succession planning is the culmination of career and leadership development. It’s where you identify — from among your developing leaders — individuals who have the most potential and whose movement toward key positions, either laterally or upwardly, you want to accelerate.

Regardless of your organization’s size, succession planning is an important activity. A mistake some smaller organizations make is feeling that they aren’t big enough to need to boost their bench strength. Many vacancies can be anticipated and planned for, but not all talent gaps can be foreseen. No matter what your size, you can’t run a business without good people ready to fill potential gaps if they occur.

If you’re not currently thinking about who will fill your shoes (or the shoes of any of your senior leaders), then you’re leaving a critical HR responsibility unattended. No one has an infallible crystal ball, but your organization should ponder contingencies if a key role in the organization were to be vacated.

Don’t put it off!

Unfortunately, many companies don’t see the urgency of succession planning. They still view succession planning as a task they’ll undertake when a clear need presents itself. In an August 2021 survey from the Society for Human Resource Management, 56 percent of HR leaders said their organization didn’t have a succession plan in place. Only 21 percent reported having a formal plan, while 24 percent said their organization had an informal plan.

What they’re missing is that having a succession plan in place can head off confusion and uncertainty, particularly if the timing of succession is abrupt, such as a sudden resignation or death. Just as important, succession planning imbues confidence throughout a business. It provides a sense that, no matter what may occur, plans are in place to keep the company moving forward and operations going. Speak to senior managers about the importance of having a plan in place for key positions in all areas of your company — whether people are planning to leave or not.

Putting together the succession plan

Businesses manage succession in different ways based on their individual cultures. Plans cover a wide range in terms of complexity and degree of formality. But most agree that the primary goal is to create a pipeline of talent by offering top performers extra support along their developmental paths.

Smaller businesses can learn a lot from the formal policies put in place at large companies, where establishing a management succession plan is a recommended practice. Some corporations have a centralized succession planning function, whereas others empower people or teams throughout the organization to manage the function on their own.

Begin your succession plan by identifying jobs whose role in the overall function of the business is too important to remain in limbo while a search is on for a replacement of some sort. Choices should be driven with an eye on your near-, mid-, and long-term business strategies. President, chief executive officer, chief financial officer, chief operating officer, and other similar positions are the likeliest candidates. In the largest companies, the board of directors plays a key role in selecting C-level succession candidates, especially for a CEO transition. (The C in C-level refers to “chief,” as in chief executive officer, chief financial officer, and chief information officer — in other words, top-ranking executives within an organization.)

But it’s not all about these C-level executives. Succession in all business-critical roles should be included in your planning. For instance, if your company leans heavily on technology (and, these days, most businesses do), you may want to add the chief information officer or other IT executive to the list. If you market your products around the world, the chief marketing officer may be another. And don’t limit the field to managers only; apply your business-critical eye to all levels in the organization. For instance, an accounting firm may need to plan just as diligently for replacing a tax specialist with in-demand expertise as it does someone in a management position. When compiling your list, talk to others throughout the company to solicit their feedback and ideas.

Pinpointing succession candidates

After you’ve selected key positions in which you want to ensure continuity, it’s time to select the individuals from your leadership development efforts who can best fill these roles. This step involves holding discussions with protégées to explain that they’re being identified for positions of increasing importance (see “Creating a flexible understanding with succession candidates,” later in this chapter), gauging their interest, and getting their buy-in.

When selecting succession candidates, consider not only skills but also how well individuals work with others throughout the company, particularly when they’ve transitioned into a position of some authority.

Here are three of the most common missteps in succession planning::

- Selecting a successor who is a mirror image of their predecessor: Of course, there’s a line of reasoning that suggests that, because the outgoing person was successful in the job, it only makes sense that a similar individual will carry on that history of achievement. It may seem reasonable, but the constancy of change dictates that what made one person successful in a job doesn’t necessarily carry over to someone else. Instead, look at the position as it exists today. From there, match the requirements and challenges to the best-qualified candidate.

- Choosing a successor because their predecessor likes them: Of course, it’s never entirely misdirected to select someone with whom you and others get along, but likeability shouldn’t be the sole factor in a succession decision. Qualifications and potential are the most important attributes to consider. Again, match job function to the person best suited to that role. Allow the reality of the job requirements to direct the decision and put feelings and friendships aside.

- Identifying only one successor: Avoid “anointing” someone for a role. Consider multiple candidates.

Companies sometimes discover that high-potential employees aren’t eager to assume senior management roles. This is understandable, as many aspects of management involve making difficult, sometimes unpopular decisions that not everyone is comfortable with. There may also be concerns about work/life balance, travel, office politics, and general stress associated with advancement opportunity. Even top performers may not see themselves as potential leaders. By addressing possible barriers, you may be able to encourage reluctant candidates to step forward.

Selecting candidates outside the company

It may seem strange at first to consider succession candidates external to the business. Often, timing is what makes the difference. If you think you have enough time, you may be able to develop an existing employee’s skills. But if your time horizon is shorter, you may need to look for an external candidate who is already somewhat prepared for the role. Still, keep in mind that there’s no guarantee that person will be able to hit the ground running, and they may not be an immediate solution. They don’t already know your business and may need time to mesh with the team and become acquainted with your operations.

With your existing staff, there are potential morale and retention issues to address if you bring someone onboard from the outside. What will existing employees’ reactions be to being passed over for a promotion? The more open line managers are with their teams in performance and development conversations, the more easily team members can accept being passed over at that particular time. If a team member is somehow convinced they’re in line for the next step, finding out that this isn’t true could come as a hard blow. Make sure that existing team members have strong development plans to prepare them for the next opportunity, whether it arrives now or sometime in the future. You also want to make sure that you thoroughly vet the incoming outside leadership candidate. You can encounter morale issues if the identified person is less of a standout than you had assumed, or if they don’t exhibit leadership qualities immediately upon coming onboard.

Creating a flexible understanding with succession candidates

Companies handle their interaction with succession candidates in different ways. Some hire and promote people with the message that they’re being groomed either for a specific position or for a more senior but unspecified leadership role; other companies hire and promote less specifically for succession and place candidates into a high-potential pool (a designated group of people who are being groomed generally for higher leadership or critical executive roles).

Exactly who succession candidates are supposed to eventually replace or what positions they’re preparing for may not be known to them — the choice to share this information is yours. If you do decide to reveal this, make sure that you establish an understanding that there are no guarantees, and the situation can change due to circumstances encountered by either the company or the succession candidates themselves. In addition, note that after succession takes place, either party may decide the fit is not right and reserves the right to back out. This arrangement also reduces the likelihood that the “heir apparent” will become frustrated if the person they’re supposed to replace doesn’t leave or retire when expected.

An approach many companies prefer today is to place emphasis not on individual positions, but on developing high potentials and letting them know that the longer they stay with the company, the more likely they are to be promoted when someone leaves. The company benefits as it maintains greater flexibility than if the preparation and investments made in individuals were designed specifically to back up a particular role or, worse, a particular person. The high-potential person benefits because they don’t have to wait for just one or a finite group of people to leave. And the person who needs the backup isn’t threatened that someone will be ready to succeed them before they’re ready to leave.

The bottom line: Because they may eventually find that initial assumptions were too aggressive or unrealistic, many companies are reluctant to be specific with high potentials about any more than a general course of development.

Developing succession candidates

In addition to the general leadership development efforts I mention throughout this chapter, you should take the follow steps with succession candidates:

- Expose them to other parts of the organization. For instance, an IT person who spends a month or two learning the ropes from a finance manager will come to understand and appreciate the importance of reducing costs and improving the efficiency of processes, many of which fall under IT’s purview. That broadened perspective makes for a better leader.

- Offer other learning and development opportunities. Although you want to offer every employee appropriate learning and development opportunities, this is even more critical for succession candidates so they can achieve their full potential. It can include varied work experience, job rotation, specific projects, and other challenging assignments. You should monitor progress carefully by evaluating how succession candidates perform in those activities. That way, you know that they’ll be ready when the time comes to move up. International experience or knowledge is among the most difficult to impart. In these cases, an expatriate assignment, wherever practical, may give the best view of nondomestic operations.

- Consider the next person in line. Succession planning means drawing up plans for more than just the next person up to bat. Be clear on success criteria for the future position and keep things moving by continuing to develop others farther down the pipeline. If some people seem discouraged that they weren’t selected as the successor, encourage them with reminders that they’re still in line for upcoming leadership opportunities. Point out that leadership openings often come out of the blue, so they need to be ready.

- Make it as much of a nonevent as possible. When planned well, succession occurs smoothly and systematically. To an outside observer, in fact, it appears seamless. That is the goal of succession planning — to ensure that the business moves forward without missing a beat, despite a change in leadership.

- Utilize the IDP process. Individual development plans (see more in Chapter 14) can be particularly useful in succession programs because they’re customized to the individual, allowing you to work with the candidate to set specific goals and the steps needed to reach them.

- Consider succession planning technology. Succession planning software applications can automate many of the tasks involved in creating a succession plan. In a nutshell, these programs allow you to readily identify upcoming succession requirements and develop necessary training and programs to address those needs. (For a full discussion of HR technology systems, refer to Chapter 3.)

Assessing succession outcomes

A succession plan is important, but it’s not enough. That’s because a plan doesn’t develop people. They need experience, advice, mentorship, and feedback from you.

Your reviews, check-ins, and performance metrics are essential to tracking progress and keeping everyone accountable. Here are a number of barometers that can prove helpful in determining what works and what may warrant reconsideration in your succession planning efforts:

- Are your new leaders successful? Are succession candidates meeting objectives and goals in their new jobs? Besides asking for a self-evaluation from the new leader themself, also talk to the people they work with to gauge their confidence level in the new leader’s direction. Again, if you identify gaps or problems in the performance in new leadership, revisit your succession process to pinpoint the source of the shortfall.

- What do participants themselves think? Consider making succession participants part of your evaluation process. What worked well for them? What was most impactful? What was least useful?

- Are new leaders staying on? As I discuss earlier in this chapter, it’s just as important to retain talented new leadership as it is to develop it. Track leadership retention rates. If your best people are leaving for other companies, determine whether your compensation package is adequate by benchmarking against similar companies in similar industries and markets. Also consider whether the responsibilities of the new position are sufficient to engage highly talented leaders.

- Is the flow of succession candidates consistent? Succession planning should be an ongoing process. Are your efforts providing the business with a reliable supply of candidates, or are there occasional gaps that could pose a problem if an important position suddenly became available? Review your program to see if you can make it more consistent across the board.

- Make evaluation a habit. Just as succession planning shouldn’t be an every-so-often consideration, so, too, should your evaluation be an ongoing responsibility. Not only does that allow you to maintain close touch with the results of your program, but it also lets you identify issues that may be impeding overall success. That gives you the opportunity to change and tweak elements of the program ongoing.

Even if replacing a top job seems too far down the road to be important today, don’t neglect succession planning. Not only is it an important practice for identifying future leaders, but it also ensures that your top talent is highlighting and poured into.

If an employee is planning to make a career change and wants to develop a skill set for this new role, make sure that their plans are in alignment with the goals of the business before the time and effort is invested.

If an employee is planning to make a career change and wants to develop a skill set for this new role, make sure that their plans are in alignment with the goals of the business before the time and effort is invested.