The atomic unit of the whole film is the frame. The unit for the recording mechanism, cine or video, is the shot. The film or video camera is a time dependent machine. Between starting and stopping the camera, an arbitrary number of frames will be captured. The difference between the frames which make up the shot are the result of change over time—that is, movement; movement either of the camera or of the scene being photographed. Discount movement and the characteristics of all the frames in the shot are found to be collectively shared. Thus though one cannot compose the image of each single frame individually, by temporarily ignoring movement, the aesthetic qualities of the frames can be determined and designed.

A frame is a still image. Among its qualities are size, viewing angle, distance, perspective, composition, colour, tone, atmosphere. Its major characteristic, however, is its flatness. A camera is a converter of three dimensions into two. While a natural phenomenon of the human brain provides an illusion of movement where none really exists, no such assistance is on hand to help create the illusion of depth. The cine photographer must work hard to provide that visual sleight of hand.

Composition of the frame uses the same devices as are used in painting and still photography: compositional structure, key (high or low), contrast, focus. Many directors and cine photographers model their images on those by famous painters of the past, particularly those artists like Vermeer whose cool domestic interiors are among the finest examples of artistic realism. Textbooks of photography often contain rules of thumb for screen composition, invoking such considerations as balance, proportion and screen ‘weight’. But because the frame is only a single one out of a continuous series, its compositional qualities can be rather different from those of a painting or a still photograph. Since the shot contains movement, the framing at the beginning may be quite different from that at the end. And the factor of movement leads to a quite different means of concentrating attention. Thus, where a painter would have to so construct the image as to lead the observer’s eye to the principal feature of the picture, the cine-photographer may depend on movement in the frame to fulfil the same purpose.

Above all, a frame is a view; a viewer’s-eye view. To design a frame is to place the viewer’s eye in front of the scene. The aim is to create the illusion that the viewers are seeing what they would see if they were they actually there at the scene. This is what can be called the ‘illusion of presence’. On this illusion is based the willing suspension of disbelief, which is central to the audience’s involvement with all television, both fact and fiction.

While the illusion of presence applies both to the cinema and to television, the difference between the two media is considerable. In the cinema the illusion is assisted by the fact that there the images are life sized. Cinema images occupy the viewer’s entire field of view. Around the screen is darkness. The size-estimation skills of the eye are applied directly to the screen image. Suppose a member of a cinema audience is seated at a distance of, say, 50 feet (15 metres) from the screen. A 6-foot (2 metre) image of a person on the screen is understood by the viewer’s eye and brain as human-sized. Now the perspective effects of the real world apply. A 3-foot (1 metre) image is seen as twice as far off: 100 feet (30 metres). From the same 50-feet distance, a face, presented five times life size on the screen is perceived as only a fifth as far away: 10 feet (3 metres).

On television, the illusion of presence is far weaker than in the cinema. A television screen occupies nothing like the viewer’s total visual field. The image is small, surrounded by other everyday objects which are usually bathed in the room’s ambient lighting. In consequence, the sizes of images on a television screen are understood not so much as literal and realistic but as symbolic. The screen itself only symbolizes, rather than actualizes, the eye’s visual field. The television screen is perceived, as the cliché has it, as a window on the world. Many older people still refer to watching television as ‘looking in’.

To define precisely the eye’s visual field is difficult. In tests, a normal pair of eyes can perceive an amazingly wide field, a horizontal angle of view of almost 180°. The owner of the eyes is, however, not normally aware of this large field, as the brain focuses on only part of it—that part on which the person is concentrating. It is as if the brain possesses a ‘zoom’ facility, able to zoom in on whatever takes the viewer’s attention. In addition, a sighted person’s eyes are never still, but constantly scan the viewing field. The smaller the area concentrated on, the smaller the total visual field scanned. The result is that a person is aware of a changing visual field which corresponds to what the brain interprets rather than what the eyes physically see. Combining the brain’s zoom facility with the scanned field of attention produces the effective field of view.

The eye estimates the size and distance of an object on a television screen by judging how much of the screen’s symbolic visual field it occupies. A head-and-shoulders image of a person on a television screen is interpreted to be at that distance at which the head and shoulders of a person would occupy the effective visual field of the eye in the real world—perhaps 3 feet (900cm).

The placement of the camera—more specifically the camera lens which represents the viewer’s eye—can be at any point in a continuous spectrum of three-dimensional space. Applying the conventional co-ordinate system used in drawing graphs, one can call the side-to-side dimension the ‘x’ axis, the up-and-down dimension the ‘y’ axis, and the front to back dimension the ‘z’ axis. If we keep the distance between the camera and the photographed object—the ‘z’ distance—constant, the ‘x’ and ‘y’ axes are seen to be circles, with the ‘z’ distance the radius and the object at the centre (Fig. 8.1). Actually, to be pedantic, the ‘y’ axis is really only a quarter of a circle. We never shoot from under the ground—never? Well, hardly ever (Fig. 8.2)—and the back half of the ‘y’ semicircle is equivalent to the front, but with the camera moved to the other side of the ‘x’ axis. The framing of a shot in a documentary film depends on where the camera is placed on each of these axes.

The camera position on the ‘x’ circle is largely responsible for the composition of the image. If the subject to be photographed were alone in space, then choosing a point along this dimension would affect only the direction from which the subject is seen: from the front, the side or the rear. Normally, one would shoot a subject or an action so that it is directed towards rather than away from the camera. The exact position is usually chosen so as to reveal as much of it as possible. Often this means selecting a three-quarter view: towards the lens as well as slightly sideways, opening up the action by spreading it horizontally, thus allowing more of it to be seen and the effects of perspective to be revealed. The choice of which sideways direction, left or right, largely depends, as will be seen later, on the preceding and following shots.

The subjects of real frames are not usually isolated; a frame of a film almost always contains a multiplicity of objects. In a scripted film, the director has the opportunity to place the objects and characters where they will make the best picture. In most documentary filming, that job must be done by choosing the camera position instead. The positioning on the ‘x’ circle affects screen relationships in a number of ways. It can determine which of the objects are ‘upstage’ (further from the camera) and which ‘downstage’ (nearer to the camera), it can ensure that none of the objects which are important for the viewer to see are masked—obscured from the camera—by others in front of them, and it can effectively control the width of the action, ensuring that it is contained within the frame. By imagining two figures standing slightly apart, one can easily see how travelling along the ‘x’ circle alters their distance and positioning on the screen (Fig. 8.3).

Fig. 8.1 The co-ordinate system.

Fig. 8.2 We never shoot from under the ground—never? Well, hardly ever.

Fig. 8.3 Travelling aiong the V circle around two figures alters their distance and screen position.

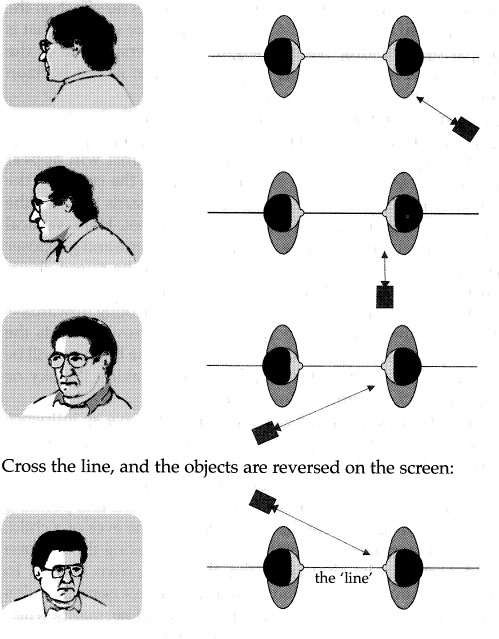

Perhaps most importantly of all, correct placement along the V circle affects which object appears on the left of screen and which on the right. If one draws a line between the subjects of a shot and extends the ends to cross the ‘x’ circle, it can be seen that any shot from one side or other of that line will place the objects consistently left and right:

Cross the line, and the objects are reversed on the screen:

As will again be seen later, this ‘line’ is an important factor to bear in mind as it affects the way the shots can be assembled. Objects on the left of frame should normally stay on that side in successive shots, objects to their right should also stick to their own side of the screen. People facing to the right of frame should continue to do so, as should those facing left. Any action should therefore be photographed from either one side of the ‘line’ or the other, never both. ‘Crossing the line’ is regarded as one of a director’s greatest potential solecisms.

Camera placement on the up-and-down axis, the ‘y’ circle, is much more restricted. The camera is hardly ever raised much above human head height, nor is it often placed below floor level. The difference in the appearance of a moderately distant lone subject, when filmed with a lens one foot above the ground and one seven feet above the ground, is barely noticeable. Yet that does not mean that raising or lowering the camera has no effect on the image, just that the pictorial impact is rather more subtle. What is changed by adjusting camera height is the perspective of the vertical features in the frame and the position of the horizon on the screen.

The normal way to photograph a subject is with the camera at the same height as the centre of interest with the lens aimed horizontally. In this position, all vertical features will appear vertical and parallel, and the horizon will be in the centre of the image. Raising the camera and tilting it downwards towards the subject produces what is called a high-angle shot. Here, vertical lines will appear to diverge towards the top of frame and get closer towards the bottom (Fig. 8.4). The horizon will be raised above the centre of the screen, thus backing much of the image with the ground. Conversely, dropping the camera and shooting upwards—a low-angle shot—will make vertical lines narrow towards the top and spread out towards the bottom, while the horizon will be displaced to a lower position in the image, making the sky or ceiling the background to most of the frame.

These effects, though not gross, nonetheless have an influence on the way the audience views the scene. Powerful characters—or those to whom the photographer wishes to ascribe power—are often shot from a low angle, backed by the sky, making them seem to dominate the view (Fig. 8.5). By lowering the lens and pointing it upwards one can look at the world through the eyes of a child. In a film about children, all of the shots taken among the children would normally be shot from the children’s own height. In contrast, the adult material would all be shot from a normal adult’s height. The result would to give an impression of normality when shooting subjects within the adult’s or the child’s world, but a contrasting appearance, marking the difference in their views when observing each other’s domain.

Fig. 8.4 Raising the camera and tilting it downwards towards the subject produces a High-Angle shot.

Fig. 8.5 Powerful characters are often shot from a low angle, making them seem to dominate the view.

Fig. 8.6 Keeping the lens horizontal leaves the horizon in place.

By raising the camera and angling it downwards, the audience sees the world from the viewpoint of a tall person or even a giant. A commonly used device is the high-angle shot at the end of a film, where the camera cranes up and looks down to provide the framing that some directors call ‘the eye of God’. The effect is supposedly to distance the audience and make the concerns of the previous sequences in the film seem insignificant in relation to the overall picture of the world. Often the only real effect is to inform the audience that the director was well enough resourced to be able to afford to use a camera-crane.

It should be remembered that these effects are the result of angling the lens to the horizontal. Keeping the lens horizontal and simply moving the camera bodily up and down to match the height of a subject leaves the horizon in place and the image undistorted (Fig. 8.6).

Choosing a shooting position along the third, the ‘z’ axis, is largely responsible for the size of the subject’s screen image. This is, as will be seen, not the same as choosing the magnification of the lens. Though there can be an infinity of different size of frame, by convention—and also by function—the frames of a film or video are usually categorized by the distance of the notional viewer’s eye. The following names are standard, though their precise meaning, the precise size to which they refer, varies from director to director, photographer to photographer. They are, from furthest away to closest in: the long shot, the wide shot, the full shot, the mid-shot, the close-up, the medium close-up, the big close-up. These names do not define a precise size, that is, a precise placement of the viewer’s eye. They are not absolute, but relative descriptions, depending on the nature of the scene and of the action taking place within it.

To choose between these frames, to determine the size of the television screen image of an object or scene, is to choose the distance at which the viewer’s eye is placed. The illusion of presence depends on a convincing placement of the viewer’s eye which in turn depends on satisfying inbuilt, as well as culturally determined, needs as to the distance between the viewer and the viewed object. Members of every culture learn early in life to defend an area of personal space around them. The size of that space depends on, among other things, the degree of formality in the situation: the more formal the situation, the further away the other person needs to keep. To allow the person actually to invade one’s personal space is to allow an act of considerable intimacy. The placement of the viewer’s eye in a scene follows similar rules. Camera placement involves the choice of an appropriate position between objectivity and intimacy.

The standard view instinctively adopted by an observer of an entire scene corresponds to what in the television vocabulary is called the wide shot. This shot gives that view of the entire scene. The eye is placed far enough away to be on the boundary of the scene but close enough to perceive the necessary details (Fig. 8.7). The wide shot is neither intimate nor distancing. It is the position taken up by a shy teenager arriving at a party: on the edge of, though not out of, the room. It corresponds to the view of the stage by the audience in a theatre. As in the theatre, it allows the viewers to feel themselves present while imagining that the real participants are unaware of the spectators’ presence.

Fig. 8.7 Far enough to be on the boundary, close enough to see the details.

It corresponds to the theatre but is not the same. The real view of a real theatrical stage has width, height and depth. It is three-dimensional. A television frame has only width and height. It is flat. In the absence of an available third dimension, other ways must be found to indicate the depth of the view. The composition of the frame is the only tool available to that end.

Movement can help, as will be seen later. But mostly depth must be indicated by a series of visual clues and tricks such as overlap, parallax and perspective. Directors call it ‘composing in depth’. These are the same devices as were developed over the centuries by painters and draughtsmen and draughtswomen. The image is first imagined as if built up of overlapping planes, like the cardboard dioramas in museum displays. Such an image can be thought of as consisting of three planes: foreground, middle-ground and background.

As on the theatrical stage, action takes place across the middle-ground. The foreground is the front of scene, the proscenium. The background is the set.

The foreground frames the action. It is an essential element of the artistic composition of the image. But it also has an even more important function. The foreground is perceived to be just behind the screen; it serves to push the action back and thus help create an illusion of depth. The human eye knows what size familiar objects should be. The difference between the actual size of an object on screen and the known real size of that object, is perceived as the effect of perspective. The contrast between the size of objects in the foreground and those in the middle ground cues the eye to perceive the middle ground as some distance away. The greater the difference between the screen size of foreground and middle ground objects, the further away the middle ground is recognized to be. The leaf of a tree shown at the same screen size as a human figure is recognized as close to the viewer with the human figure much further away.

Fig. 8.8 A fence, part foreground, part middle-ground, part background.

Movement in a frame will be considered elsewhere, but it is worth noting here that foreground movement is often a feature of the wide shot. Movement of whatever frames the foreground of a shot adds realism. However, such movement must be handled with care. Foreground movement is magnified. Changes which would not be seen in the middle ground or background are clearly visible. Because the foreground is closest to the viewer it easily distracts attention. Movement in the foreground, unless continuous and random, like water rippling or leaves trembling in the air, takes the spotlight from where it should be: on the action. But such movement, if small and complementary rather than conflicting, can add greatly to the atmosphere of the image. Photographers frequently ensure that in a wide shot of an open air scene, for example, some foliage is included, drooping into the foreground top of the image. This is commonly called dingle. It is not unknown for an assistant to be deputed to shake it about a bit, to make sure that it is seen to move in an appropriate way.

The background of a frame is the set and setting for the middle ground action. It has functional and symbolic effects. Functionally, it pushes the middle ground action forward towards the viewer. Between the foreground proscenium and the background set, the action is forced into the middle ground. The illusion of presence, which depends on the illusion of depth, depends in turn on the action being in front of the background and behind the foreground.

Unlike a cardboard museum display, an image is not, of course, composed of simple flat planes. Though foreground, middle ground and background are distinguished from each other, in many images they are part of a single feature running from foreground to background. The illusion of depth in a frame is enhanced by allowing long features to run both in depth as well as across the image. A fence or wall, typically, would be so captured as not to run across the frame but at an angle, with part forming the foreground, part the middle ground, and the rest running away into the distance of the background (Fig. 8.8). Shooting at an angle makes the effects of perspective most evident.

Atmospheric perspective also contributes to the sense of distance. If very far away, the background to a scene may be fainter in tone that the middle ground. As in a watercolour painting, the further the background, the paler its tones and colours are likely to be. This is the natural consequence of the absorption of light by dust or mist in the atmosphere and is not an artefact under the control of the film maker.

The background of a shot does more, however, than just contribute to the three-dimensional quality of an image. The set of a scene tells the viewer where the action is taking place. The choice of background therefore has important symbolic and atmospheric consequences. It characterizes the location not only geographically but also adds emotional value to the scene. Choosing, or even dressing, the background is an essential part of placing the action in its physical, emotional and aesthetic context. Its contribution therefore to the content, not just the location, of the scene should not be underestimated. Film-makers usually take a great deal of trouble to ensure that the background to a wide shot is chosen to contribute as much to the meaning of the scene as possible.

The long shot is usually captured from further away than the wide shot. It is usually flatter. The view is that of an observer totally disconnected from the action. The actual distance depends on the nature of the action and the scenic environment.

Where the wide shot reveals the action within its environment, the long shot focuses attention on the overall environment itself, of which the action is merely one element. Thus landscapes, both rural and urban, are what the long shot is usually all about, placing the action within a context of space and atmosphere.

Because of its nature, the long shot is not so much composed of a foreground, a middle-ground and a background, but is mostly all background. Foreground detail, which plays such an important function in the wide shot, may also be introduced into the long shot, but serves merely to emphasize the distance of the rest of the image. It is the middle ground that is most notable by its absence.

Where the wide shot is introductory to a scene or sequence, giving the viewer on overall impression of the scene, the long shot is often used as a device for temporarily withdrawing from the action and looking at it dispassionately from a distant perspective. The long shot dwarfs the subject.

Distance has its disadvantages on the television screen. Where in the cinema, the small size of the significant feature in the frame makes its own point, on television such a screen size makes the feature vanishingly small. In the domestic environment where most television is viewed, such a feature may not be noticed at all. The line structure of the television screen makes very small features on the screen physically unclear. An object needs at least a few screen lines to be recognizably drawn. Of the 625 lines making up a television frame (525 for NTSC as in the USA) only 576 (480) actually appear on the screen. Any feature less than 1/576 (1/480) of the height of the screen cannot appear, if at all, as more than a single dot. Thus there is a lower limit to the size a feature can be, if the viewer is to both observe and clearly interpret it. So the long shot is more useful to the cinematic film-maker than to the television documentarist. That is not to say that it should be entirely avoided. Only that great care needs to be taken with its use.

Because of its dispassionate nature and its disconnection with the action, and also because movement in the scene is minimized by the distance of the viewer’s eye, the long shot lends itself most of all to the artifices of beautiful composition. Here the craft of the landscape painter is most profitably brought to bear on the image. Where in other shots too much attention to picture-making might distract attention from the substance of the image and the concentration on the action, the film-maker has an obligation to make the long shot as aesthetically pleasing as possible. And the problems associated with the small size of the main feature within the overall arrangement make care in frame composition particularly necessary. A tiny figure in a landscape cannot depend on movement to draw the viewer’s attention. The structural composition of the image is the only way to concentrate attention on that particular part of the frame.

In the wide shot and the long shot we are looking at the entire scene as a whole. As we come closer, we begin to pick out individual groups of objects or characters. It is impossible to say at what point a wide shot becomes a group; there is no sharp dividing line between them. But generally group shots contain no more than three or four, at the very most five, characters or objects. Any larger, and the group becomes too big to maintain its unitary nature.

Why would one wish to select out a group from the generality of a scene? Usually because one wishes to concentrate on the interactions between its members. To do this effectively, the camera must be placed in exactly the right position. In a scripted film, the director is responsible for arranging the characters in the mis-en-scène in the most dramatic and attractive way. In a documentary it is sometimes possible for the film-maker to interfere in an event enough to ask its participants to take up particular positions, but usually the composition of the image is controlled by careful positioning of the camera.

Groups of people interacting with each other mostly arrange themselves automatically and unconsciously in a rough circle. With the camera positioned outside the ring, some of the participants will necessarily have their backs to the viewer. More problematically, those in the front will mask—obscure from the camera—those at the back. Whatever actions or interactions take place within the circle will be hidden from the lens. The effect on the viewer is to be excluded from what is going on. In this situation the photographer, rather than attempting to peek between the foreground figures, will usually try to insinuate him- or herself into the circle, becoming part of it, and thus able to gain a viewpoint similar to the others in the group. As a result the sense of the group as a whole may be lost as the camera will only be able to see a restricted section—which section depending on the direction in which the lens is pointed.

Under such circumstances the previously mentioned concept of the ‘line’ becomes all important if the viewer is not to lose all geographical sense of the set-up: who, in other words, is standing where. With the camera positioned in the centre of the circle it is easy to see how different interactions between different members can place the ‘line’ now on this side of the camera, now on that. In consequence a particular speaker may first appear on the left of screen looking towards the right, later he or she may be found on the right, looking left. As a result, the audience may be left totally confused. It is possible, by very careful selection, to help the viewers make sense of such a sequence of images, but it is quite difficult. Most directors at the start of their careers try at least once to shoot a multiway discussion ‘in the round’. The experiment is usually not repeated.

Even in a group, most interactions are one-to-one. In fact, nearly all human interactions are between no more than two individuals. When addressing an audience, a speaker’s remarks will almost always be targeted to a single listener, or to a series of single listeners. Thus by far the commonest group shot is one containing only two participants: a speaker and a listener. It is called a two-shot, often abbreviated as 2-S (Fig. 8.10).

Two-shots can be of a range of sizes: from those which include both characters almost full length to those in which one of the characters appears as no more than a foreground frame for the other—the so-called ‘over-the-shoulder’ view. The two parameters which the photographer can vary are: the camera’s position along the ‘z’ axis, the distance, that is, from the camera to its subjects. This, given constant lens magnification, determines their size on screen. The other variable is the camera position along the ‘x’ circle, which controls the angle between the lens and the ‘line’ joining the two figures. It is this angle which establishes the composition of the frame.

Where two people stand talking to each other, the simplest way to view them is flat on (Fig. 8.9). There are a number of disadvantages to this approach. Unless the characters are looking towards—‘favouring’—the camera, as part of a photocall perhaps (Fig. 8.11), both will be seen in profile, a viewpoint which, though sometimes striking and making a strong interaction between the two participants almost visible, totally cuts out the onlooker and can therefore be rather alienating (Fig. 8.12). Such a view also ignores the preference for ‘composing in depth’, the aim of giving an illusion of three dimensions on the two-dimensional television screen.

In addition, the flat-on two-shot can only work where the figures are reasonably distant and their relatively small size allows them both to fit easily onto the screen at the same time. Where a closer two-shot is called for, filming the characters flat on gives rise to a split image, with the faces pushed to the edge of frame and an unsightly empty space left in the middle (Fig. 8.13).

In most cases, a two-shot will be so arranged that one of the characters is closer to the camera than the other, in other words so that the axis between them will be at an angle to the lens (Fig. 8.14). This brings in the necessary perspective effects to give depth to the image. The angle is controlled by moving the camera around on the ‘x’ circle, which at the same time determines how far apart the two figures appear: the narrower the angle, the tighter together. Where the figures are to appear large on screen, they will need to be brought very close together, at an angle to the lens approaching zero, that is to say, the ‘line’ between the two protagonists will be almost parallel to the axis of the lens. The foreground figure will be reduced to a sliver bordering the frame (the over-shoulder shot (Fig. 8.15) and will eventually be excluded altogether, leaving us with an image of just one of the subjects at a narrow angle to the lens (Fig. 8.16). This is the standard television image of an interviewee; it implies that the second party to the interaction is present but just out of frame (Fig. 8.17).

If both characters are looking at each other and at an angle to the camera, clearly only one of the pair will be favouring—facing towards—the lens. This will be the ‘upstage’—away from the audience—character. Controlling what is ‘upstage’ and what ‘downstage’ are important compositional aids to directing the audience’s attention to the action. Generally, the effect of perspective will be to point the viewer upstage rather than down, particularly when the upstage character or action is placed centrally on the screen. If, for example, one of the figures in the shot is performing an action with the hands, most photographers will try to position themselves so that the action is central and performed by the upstage hand.

The long shot gives the most objective view of the subject, the wide shot less so. For greater intimacy, we define the images in terms of their subjects. A shot of two people is called a two-shot, a shot of one person is usually called a single. Categorized by its size on the screen, the full shot refers to a head-to-foot human image.

The full shot, common on the cinema screen, is among the least used in television documentary work. In part this is because of the difficulty of establishing an attractive composition for the image—the unsatisfactory relationship between the upright human figure and the recumbent (greater width than height) screen. In addition the detail in which a human figure’s face can be seen in full shot is insufficient to read its expression clearly.

The mid-shot, however, is much more useful. It contains within the frame a human figure from waist to top of head (Fig. 8.18). It corresponds to a placing of the viewer’s eye half way between objective and intimate. The mid-shot is the view of a person we get when initially introduced and shaking hands. It is the chosen view of the weather forecaster. It equates to the distance taken up by the audience when a formal lecturer says: gather round and look at what I am doing. The audience gathers round, but not so closely as to feel that each individual member is being individually spoken to. A television mid-shot is close enough for us to read the screen personage’s expression and at the same time see the actions of the hands.

The mid-shot may be able to bring to the composition the same elements—foreground, middle ground and background—as make up the wide shot. Moreover the foreground may often be part of the action. In a demonstration, for instance, though the demonstrator is in mid-shot, the action the demonstrator performs will be seen as foreground action. This unity makes the mid-shot size particularly useful.

The mid-shot, being intermediate between the wide shot and the sizes closer in, is also available for linking the two together. In a scene with many participants, it is not always easy when going from a wide shot to a medium close-up to identify which character is the subject of the medium close-up. The mid-shot functions as an intermediary size; with it we can identify the subject of the following closer images.

The medium close-up, often abbreviated to MCU, is the typical television framing of a human subject when speaking. It is the standard intimate view of a person on the screen (Fig. 8.19). If an average were constructed of all the frames shown on a television channel over the period of a day, it would probably approximate to a medium close-up of a single speaker.

Film photographers differ in the tightness with which they frame a medium close-up. They also take care to keep important parts of the image away from the very edge of the screen. Since television sets vary considerably in their adjustment, screen images are composed to allow for sets which are ‘underscanned’, that is, those in which the screen cuts off a margin all round the picture. The image is composed within a ‘safe area’, often marked on the camera’s viewfinder (Fig. 8.20).

In general one can say that an MCU is that shot which contains within the frame a person’s image from shoulders to top of head. It corresponds to our normal view of a conversational partner. When we speak individually or privately to another person, the image of which we are conscious approximates to the television medium close-up. It is a view of some intimacy. Anything said to the camera by someone in medium close-up will be taken as addressed to the viewer—and to the viewer only. It is the standard image of the news reader, of the television presenter, of any other television personage who has a licence to address us, the audience, directly. That is to say, who may look straight into the lens rather than off to the side of it, a licence which is strictly reserved.

In a framing as tight as the medium close-up, there are fewer planes available for composition of the image. In general there is the subject of the shot him or herself and the background. With the focus on the foreground head and shoulders, the background will often be allowed to go soft; that is, slightly out of focus. This will help in defining the depth of the shot. There is not enough space left on the screen to define the background with enough detail for it to add materially to the content of the image. The background will often add little more than a decorative element.

As a result, many film-makers try to avoid showing the background to a medium close-up in any detail. A plane coloured by a single tone is often chosen, sometimes with a decorative splash or streak of light. In an exterior, the background is often chosen to be far away enough from the subject to fall totally out of focus.

Modern techniques may divorce the background from reality altogether. The Blue Screen technique allows any part of the image detected as blue in colour (or green or red, but blue is commonly used because it is not normally found in human skin tone) to be replaced by a picture from another source. Thus any kind of background can be inserted behind a speaker’s head, even moving images. Though the latter can add greatly to the interest and attraction of the frame, movement behind the head will always be a distraction from the foreground—which is usually the medium close-up subject’s speech. Whether this is an advantage or a disadvantage depends on the documentarist’s attitude to the material. Many of today’s film-makers use such a composite image to add their own comments to what is being said. It must be recognized, however, that this will thrust into the audience’s consciousness an immediate awareness that there is a film-maker at work, rather than accepting the flow of frames and images with the suspension of disbelief that is a more traditional film-maker’s aim.

Close-ups fill the screen with the image of the subject. A big close-up concentrates on only a part of it. As with the medium close-up, photographers interpret the size of the shot in different ways. One photographer’s close-up might be another’s big close-up. The differences between close-up, big close-up or even very big close-up (Fig. 8.21)—usually abbreviated to CU, BCU and VBCU—are related, not so much to screen size, but to the actual size of the subject of the frame. A close-up of a fingernail, for instance, will necessarily be taken from a closer viewing position than that of the finger to which it is attached, and both will be shot from closer than the CU of a whole hand.

The use of the close-up distinguishes the cinema film from the television variety. The CU is one of the key images of the television documentary because unlike in the cinema, where the viewer can choose which part of the screen to look at, the small size of the television screen makes it impossible for the viewer’s eyes to concentrate on only the relevant part of the image. The television film-maker must do the selection on behalf of the viewer. This responsibility is an important one. It means that the director or cine-photographer must determine in advance what the response of the viewer to the image is likely to be. The flow of frames should ideally be those that the viewers would have selected—albeit unconsciously—if they had really been present at the scene. Because the director makes the choice on behalf of the viewer, it gives him or her the opportunity to draw attention to details of the scene which have particular pertinence to the subject of the shot. The art of choosing close-ups is the art of selecting the significant detail which gives meaning to the scene.

The placement of the viewer’s eye in close-up or big close-up position has implications for the way the viewer appreciates the image, particularly when the subject of the frame is a human face. Where, with an MCU, the viewer’s eye is placed at a conversational distance from the subject, in a CU or even more in a BCU, the viewer’s eye is placed much closer—so close, in fact, as to give the viewer the feeling, consciously or unconsciously, that he or she is invading the subject’s personal space. In addition, the concentration on a single close image is symbolically suggestive that the normal scanning of the scene performed by an observer’s eyes has been halted. The close-up of a face is the equivalent of staring hard at somebody. The viewer may become aware of feeling this whether or not the director wishes this to be the impression given.

The end result of these effects on the viewer of the close-up of a face may be subtly to alter the relationship between the viewer on the subject of the frame. The wide shot makes the viewer an observer of a scene which promises to, but does not yet, involve him or her personally. The mid-shot puts the viewer in the auditorium at a lecture or presentation. Because it is so close to the view of a person with whom we are conversing, the MCU can convince us that we are participating in a conversation. We can be made to suspend our disbelief that the person on the screen is aware of our presence. Hence the familiar pretence of television presenters: ‘See you at the same time next week,’ they say, when what they really means is you will see them. But the close-up and big close-up place the viewer in far too intimate a relationship for the viewer to accept that the person on the screen could possibly be aware of his or her presence. The viewer has been given a cloak of invisibility. Thus the close-up and big close-up make the viewer an observer again, rather than a participant.

The biggest close-ups of all begin to approach the view of the subject as one would see it through a microscope. There is no question of the subject of the image being aware of the viewer’s presence, any more than an amœba on a slide understands that it is being looked at by a researcher. A big close-up of a familiar object such as a face can alienate the viewer, making the subject of the frame seem strange; just as a spoken word can, by constant repetition, become drained of its meaning so that one becomes aware, as if for the first time, of its sound.

Such an unusual view of a subject, particularly a human face, gives it unusual significance. A viewer will expect to see something of particular importance in the frame—and will usually find it, even when the director or photographer did not mean it that way.

If the most typical framing in the television documentary is the medium close-up, it is in the form of the talking head that it is most often found (Fig. 8.22). ‘Talking head’ is, of course, a pejorative expression. Such an image is considered too static and too unilluminating. It is thought to emphasize the literary, the words, in a medium that is above all visual. But while the talking head is criticized as a motif, yet it is the principal means by which the television documentary carries spoken exposition, explanation, narrative and expressed emotion. Human communication depends on far more than just words. The expressions that pass across a speaker’s face while telling a story that has personal significance adds immeasurably to the text. Will Eisner, the great comic-book artist, emphasized the expressive potential of the human face: ‘The face provides meaning to the spoken word. From the reading of a face, peope make daily judgements, entrust their money, political future and their emotional relationships.’1 No film-maker should dismiss the power of the talking head to touch the audience.

The talking head may be speaking directly to the camera or to a seen or unseen interviewer. Though the phrase refers only to the head, what it really means is no more than a single person on the screen speaking. And this can actually be shown in every size of shot, from wide to close-up. Each of these framings will have its own effect on the viewer’s response to the speaker.

It should not be thought inevitable that the closer the shot, the greater the communication. People also use their hands and their bodies to make an important contribution to the meaning of what they say. The more we concentrate on the face alone, the more we depend on purely spoken rather than total language; for some speakers, the closer we approach, the less information we receive.

A talking head in medium close-up is shown at the conventional conversational distance; intimacy is retained. If the speaker is addressing the camera, the viewer feels that he or she is being personally addressed. If the speaker is talking to someone off screen, the viewer is made to feel party to a private conversation. In mid-shot, the psychological distance between the viewer and the person on screen increases in proportion to the physical distance. As the frame widens, the speaker’s words are addressed more to the generality and take on more of the attributes of a public performance. In full wide shot, the speaker’s face may become so small on screen that the synchronization between the sound and the speaker’s lip movements may be undetectable by the viewer. In this case, the speaker’s words become—effectively—a voice-over. Such width of frame is purposeless when the speaker is addressing camera. When the speaker is addressing an off-screen presence, the conflict between the depersonalization of the speaker by going wide, the characterization made possible by showing more of the speaker’s environment, as well as the greater visual design possibilities of a frame not solely taken up with displaying the speaker, is a conflict that may be hard to resolve.

The composition of the medium close-up talking-head frame betrays a revealing factor. By convention, the on-screen speaker is allowed ‘talking room’ also sometimes called ‘looking room’. That means that the positioning of the head on the screen is not central, but displaced so that there is more space in front of than behind the head. It is as if the edge of the frame represents a solid obstruction, which must be kept at a distance so as not to discomfort the speaker. Most film-makers are aware of this convention as an empirical finding: the framing of the head looks more satisfactory that way.

The actual reasons for this judgement remain obscure. It may be the need to place the subject’s eyes near the centre of the frame. It may be that the face has a greater screen ‘weight’ than the other side of the head, thus requiring a more central position on the screen. Or it might be that the on-screen character’s speech or look is thought of as having a physical reality which, though invisible, must be allowed space on the screen—leaving room for a speech-balloon, as it were. It also seems likely that keeping the edge of the frame some distance from the face shows the viewer that the speaker’s conversational partner is more than that minimum distance away, thus confirming that the exchange between them is not personal but public. It is certainly the case that placing the edge of the frame too close to the speaker’s face gives the viewer a strange feeling of claustrophobia—not unlike watching a cat directly facing, and staring at, a wall.

Whether a speaker on the television screen addresses the camera or looks off-camera has traditionally been a matter of convention. The television presenter is usually the only character to appear on the screen who is in some sense licensed to address the viewer directly. This permission is somewhat paradoxical as it contradicts common sense: the sure and certain knowledge that whatever is happening in the scene has no real connection with the viewer observing the events on the television set.

The presenter role has a long and august tradition. Shakespeare uses a presenter in Henry V: the character called Prologue, who declaims: ‘Oh for a muse of fire…’ and is the only member of the cast permitted to speak directly to the theatre audience for fear of threatening the believability of the play. Ultimately the convention stems from the theatre’s most ancient roots—the Greek religious drama. Is it too far fetched to see the television presenter as still in some ways analogous to the religious shaman or priest, the sole permitted intermediary, the bridge-builder between the congregation and the invisible Gods?

This question of eye-line—the direction to which the on-screen speaker is looking—touches on the instinctive human response to eye-contact. People are incredibly sensitive to eye-contact. A pedestrian in the street can tell from a considerable distance away, whether an approaching person is looking at him or her. In a television discussion if a participant even momentarily looks away from the presenter and directly at the camera, the effect on the viewer can be quite shocking and disorienting. For the accepted convention has been broken. It is as if the viewer’s presence, conventionally that of an unseen bystander, is suddenly acknowledged by the participant. But since the viewer knows full well that he or she is not in reality present, the experience can undermine the suspension of disbelief and make plain the artificiality of the situation. Perhaps it is only convention which permits us to accept such a falsification from a licensed presenter, where it would not be acceptable from a ‘real’ participant.

Though it might seem that for an on-screen speaker to address the camera directly may provide a greater intimacy, that is not usually the case. Human communication depends for its total effect on an huge richness of non-verbal communication devices constantly being played out in the course of a conversation. When a speaker addresses the camera, there is no feedback, no response, from the glass lens. The result is to make the communication very much a one-way affair. Speech to camera therefore always reveals a certain artificiality. It has the feel of a lecture, even when a highly practised presenter tries hard to make the text seem improvised and personal. Add to that the peculiarly English interdict on using hand gestures to aid expression, and the presenter is driven by default to using a strangely mannered way of emphasizing individual words instead—often quite irrespective of their significance or importance in the sentence.

On the other hand, where a speaker is addressing a real person off camera, the flavour of the exchange is much more realistic. In fact the speaker can often come to seem quite oblivious to the camera’s presence. In this case, the question arises: where to put the person to whom the on-screen speaker is speaking for this will determine the direction in which the speaker looks. The human eye, as previously noted, is highly sensitive to the direction of the look and can discriminate between exquisitely small differences in angle. Though the speaker may be addressing someone sitting or standing as close to the camera as can be, the viewer will be aware immediately, that the camera itself is not being spoken to.

The interviewer, by which is meant the person to whom the on-screen speaker is talking, may be placed in a wide range of positions. Usually this will be to one side or other of the camera, though some directors favour a position in line with and underneath the lens. Clearly, above the lens is impossible for practical reasons (unless the interviewer contrives to be suspended in the air.)

In general, the closer to the lens that the interviewer places him or herself, the more intimate the impression given. As we have seen earlier, the single image of an interviewee, speaking to someone just off camera, can be seen as the end result of a process of magnifying a two-shot, bringing the line between the pair closer and closer to the axis of the camera. Such a shot implies that the viewer is right next to the interviewer. Thus with the interviewer placed right next to the lens, the viewer is given the feeling that, though not being addressed directly, he or she is being included in the conversation.

Equally, the further from the lens that the interviewer sits or stands, the more the viewer is made a mere spectator or unconnected observer. The limit is when the speaker is seen in profile: the viewer is made to feel almost totally unconnected with the events on screen.

Placing the interviewer under the camera does bring the speaker’s eye-line onto the vertical axis of the lens. Because of the eye’s sensitivity to the direction of a speaker’s look, the viewer is still aware that he or she is not being directly addressed. However, the fact that the speaker is constantly looking below the lens can give the interviewee’s eyes a hooded look. The viewer feels that the interviewee is constantly looking down, making him or her seem somewhat shamefaced or even evasive.

In a film where the presenter or interviewer appears on screen, the back of the interviewer’s head and top of the shoulder can be brought into the image in the framing known as ‘over the shoulder’. This is the limiting magnification of a two-Shot—any further in and the interviewer would be lost from sight altogether. An image like this fixes the speaker’s eye-line in a geographical relationship with the interviewer. It also makes explicit to the audience that the speaker is not in fact speaking to them, but emphasizes the reality of the exchange between interviewer and interviewee. The viewer again becomes a detached spectator, albeit included to an extent by close proximity to the exchange, but what is lost in intimacy may be made up for by making explicit the reality of the speaker’s conversational partner.

Note

1 Comics and Sequential Art 1985