CHAPTER 2

Information Security Governance

In this chapter, you will learn about

• Business alignment

• Security strategy development

• Security governance activities

• Information security strategy development

• Resources needed to develop and execute a security strategy

• Obstacles to strategy development and execution

• Information security metrics

The topics in this chapter represent 24 percent of the Certified Information Security Manager (CISM) examination. This chapter discusses CISM job practice 1, “Information Security Governance.”

ISACA defines this domain as follows: “Establish and/or maintain an information security governance framework and supporting processes to ensure that the information security strategy is aligned with organizational goals and objectives.”

Security governance should be the wellspring from which security-related strategic decisions and all other security activities flow.

Properly implemented, governance is a process whereby senior management exerts strategic control over business functions through policies, objectives, delegation of authority, and monitoring. Governance is management’s oversight for all other business processes to ensure that business processes continue to effectively meet the organization’s business vision and objectives.

Organizations usually establish governance through a steering committee that is responsible for setting long-term business strategy, and by making changes to ensure that business processes continue to support business strategy and the organization’s overall needs. This is accomplished through the development and enforcement of documented policies, standards, requirements, and various reporting metrics.

Introduction to Information Security Governance

Information security governance typically focuses on several key processes. Those processes include personnel management, sourcing, risk management, configuration management, change management, access management, vulnerability management, incident management, and business continuity planning. Another key component is the establishment of an effective organization structure and clear statements of roles and responsibilities. An effective governance program will use a balanced scorecard, metrics, or other means to monitor these and other key processes. Through a process of continuous improvement, security processes will be changed to remain effective and to support ongoing business needs.

Information security is a business issue, and organizations that are not yet adequately protecting their information have a business problem. The reason for this is almost always a lack of understanding and commitment by boards of directors and senior executives. For many, information security is only a technology problem at the tactical level. Recent events have brought the issue of information security to the forefront for many organizations. The challenge is that because of a lack of awareness or cybersecurity savviness, organizations still struggle with how to successfully organize, manage, and communicate about it at the boardroom level.

To be successful, information security is also a people issue. When people at each level in the organization—from boards of directors to individual contributors—understand the importance of information security and their own roles and responsibilities, an organization will be in a position of reduced risk. This reduction in risk or identification of a potential security event results in fewer incidents that, when they do occur, will have lower impact on the organization’s ongoing reputation and operations.

Information security governance is a set of activities that are established so that management has a clear understanding of the state of the organization’s security program, its current risks, and its direct activities. A goal of the security program is to continue to contribute toward fulfillment of the security strategy, which itself will continue to align to the business and business objectives. Whether the organization has a board of directors, council members, commissioners, or some other top-level governing body, governance begins with the establishment of top-level strategic objectives that are translated into actions, policies, processes, procedures, and other activities downward through each level in the organization.

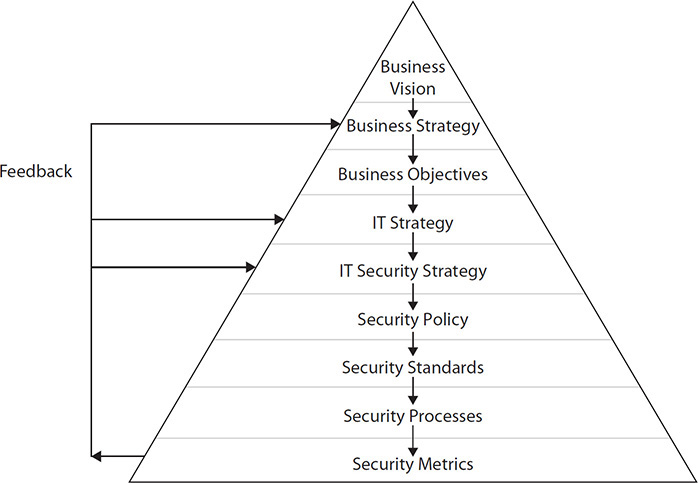

For information security governance to be successful, an organization must also have an effective IT governance program. IT is the enabler and force multiplier that facilitates business processes that fulfill organization objectives. Without effective IT governance, information security governance will not be able to reach its full potential. The result may be that the proverbial IT bus will travel safely but to the wrong destination. This is depicted in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1 Vision flows downward in an organization.

While the CISM certification is not directly tied to IT governance, this implicit dependence of security governance on IT governance cannot be understated. IT and security professionals specializing in IT governance itself may be interested in ISACA’s Certified in the Governance of Enterprise IT (CGEIT) certification, which specializes in this domain. While IT governance and information security governance may be separate, in many organizations the governance activities will closely resemble each other. Many issues will span both IT and security governance bodies, and a number of individuals will participate actively in both areas. Some organizations may integrate IT and information security governance into a single set of participants, activities, and business records. The most important thing is that organizations figure out how to establish governance programs that are effective for achieving desired and documented business outcomes.

The purpose of security governance is to align the organization’s security program with the needs of the business. The term information security governance refers to a collection of top-down activities intended to control the security organization (and security-related activities in every part of the organization) from a strategic perspective to ensure that information security supports the business. These are some of the artifacts and activities that flow out of healthy security governance:

• Objectives These are desired capabilities or end states, ideally expressed in achievable, measurable terms.

• Strategy This is a plan to achieve one or more objectives.

• Policy At its minimum, security policy should directly reflect the mission, objectives, and goals of the overall organization.

• Priorities The priorities in the security program should flow directly from the organization’s mission, objectives, and goals. Whatever is most important to the organization as a whole should be important to information security as well.

• Standards The technologies, protocols, and practices used by IT should be a reflection of the organization’s needs. On their own, standards help to drive a consistent approach to solving business challenges; the choice of standards should facilitate solutions that meet the organization’s needs in a costeffective and secure manner.

• Processes These are formalized descriptions of repeated business activities that include instructions to applicable personnel. Processes include one or more procedures, as well as definitions of business records and other facts that help workers understand how things are supposed to be done.

• Controls These are formal descriptions of critical activities to ensure desired outcomes.

• Program and project management The organization’s IT and security programs and projects should be organized and performed in a consistent manner that reflects business priorities and supports the business.

• Metrics/reporting This includes the formal measurement of processes and controls so that management understands and can measure them.

To the greatest possible extent, security governance in an organization should be practiced in the same way that the organization performs IT governance and corporate governance. Security governance should mimic corporate and/or IT governance processes, or security governance may be integrated into corporate or IT governance processes.

While security governance contains the elements just described, strategic planning is also a key component of governance. Strategy development is discussed in the next section.

Reason for Security Governance

Organizations in most industry sectors and at all levels of government are increasingly dependent on their information systems. This has progressed to the point where organizations—including those whose products or services are not information related—are completely dependent on the integrity and availability of their information systems to continue business operations. As an information security professional, it is imperative that you understand the priority of the business with regard to confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA). All three of these should be considered when building out the security governance structure, but the type of information used by the business will drive the priority that is given to confidentiality, integrity, and availability. Information security governance, then, is needed to ensure that security-related incidents do not threaten critical systems and their support of the ongoing viability of the organization.

Among information security professionals, it is a known fact that without adequate safeguards, information technology assets that are Internet accessible would be compromised in mere minutes of being placed online. Further, many if not all information technology assets thought to be behind the protection of firewalls and other control points may also be easily accessed and compromised. The tools, processes, and controls needed to protect these assets are as complex as the information systems they are designed to protect. Without effective top-down management of the security controls and processes protecting IT assets, management will not be informed or in control of these protective measures. The consequences of failure can impair, cripple, and/or embarrass the organization’s core operations.

Security Governance Activities and Results

Within an effective security governance program, an organization’s senior management team will see to it that information systems necessary to support business operations will be adequately protected. These are some of the activities required to protect the organization:

• Risk management Management will ensure that risk assessments will be performed to identify risks in information systems and supported processes. Follow-up actions will be carried out that will reduce the risk of system failure and compromise.

• Process improvement Management will ensure that key changes will be made to business processes that will result in security improvements.

• Event identification Management will be sure to put technologies and processes in place to ensure that security events and incidents will be identified as quickly as possible.

• Incident response Management will put incident response procedures into place that will help to avoid incidents, reduce the impact and probability of incidents, and improve response to incidents so that their impact on the organization is minimized.

• Improved compliance Management will be sure to identify all applicable laws, regulations, and standards and carry out activities to confirm that the organization is able to attain and maintain compliance.

• Business continuity and disaster recovery planning Management will define objectives and allocate resources for the development of business continuity and disaster recovery plans.

• Metrics Management will establish processes to measure key security events such as incidents, policy changes and violations, audits, and training.

• Resource management The allocation of manpower, budget, and other resources to meet security objectives is monitored by management.

• Improved IT governance An effective security governance program will result in better strategic decisions in the IT organization that keep risks at an acceptably low level.

These and other governance activities are carried out through scripted interactions among key business and IT executives at regular intervals. Meetings will include a discussion of the impact of regulatory changes, alignment with business objectives, effectiveness of measurements, recent incidents, recent audits, and risk assessments. Other discussions may include such things as changes to the business, recent business results, and any anticipated business events such as mergers or acquisitions.

These are two key results of an effective security governance program:

• Increased trust Customers, suppliers, and partners trust the organization to a greater degree when they see that security is managed effectively.

• Improved reputation The business community, including customers, investors, and regulators, will hold the organization in higher regard.

Business Alignment

An organization’s information security program needs to fit into the rest of the organization. This means that the program needs to understand and align with the organization’s highest-level guiding principles including the following:

• Mission Why does the organization exist? Who does it serve, and through what products and services?

• Goals and objectives What achievements does the organization want to accomplish, and when does it want to accomplish them?

• Strategy What are the activities that need to take place so that the organization’s goals and objectives can be fulfilled?

To be business aligned, people in the security program should be aware of several characteristics about the organization, including the following:

• Culture Culture includes how personnel in the organization work, think, and relate to each other.

• Asset value This includes information the organization uses to operate. This often consists of intellectual property such as designs, source code, production costs, and pricing, as well as sensitive information related to not only its personnel but its customers, its information-processing infrastructure, and its service functions.

• Risk tolerance Risk tolerance for the organization’s information security program needs to align with the organization’s overall tolerance for risk.

• Legal obligations What external laws and regulations govern what the organization does and how it operates? These laws and regulations include the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS), European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) standard. Also, contractual obligations with other parties often shape the organization’s behaviors and practices.

• Market conditions How competitive is the marketplace in which the organization operates? What strengths and weaknesses does the organization have in comparison with its competitors? How does the organization want its security differentiated from its competitors?

Goals and Objectives

An organization’s goals and objectives specify the activities that are to take place in support of the organization’s overall strategy. Goals and objectives are typically statements in the form of imperatives that describe the development or improvement of business capabilities. For instance, goals and objectives may be related to increases in capacity, improvements of quality, or the development of entirely new capabilities. Goals and objectives further the organization’s mission, helping it to continue to attract new customers or constituents, increase market share, and increase revenue and/or profitability.

Risk Appetite

Each organization has a particular appetite for risk, although few have documented that appetite. ISACA defines risk appetite as the level of risk that an organization is willing to accept while in pursuit of its mission, strategy, and objectives, and before action is needed to treat the risk.

Risk capacity is related to risk appetite. ISACA defines risk capacity as the objective amount of loss that an organization can tolerate without its continued existence being called into question.

Generally, only highly risk-averse organizations such as banks, insurance companies, and public utilities will document and define risk appetite in concrete terms. Other organizations are more tolerant of risk and make individual risk decisions based on gut feeling. However, because of increased influence and mandates by customers, many organizations are finding it necessary to document and articulate the risk posture and appetite of the organization. This is an emerging trend in the marketplace but is still fairly new to many organizations.

Risk-averse organizations generally have a formal system of accountability and traceability of risk decisions back to department heads and business executives. This activity is often seen within risk management and risk treatment processes, where individual risk treatment decisions are made and one or more business executives are made accountable for their risk treatment decisions.

In a properly functioning risk management program, the chief information security officer (CISO) is rarely the person who makes a risk treatment decision and is accountable for that decision. Instead, the CISO is a facilitator for risk discussions that eventually lead to a risk treatment decision. The only time the CISO would be the accountable party would be when risk treatment decisions directly affect the risk management program itself, such as the selection of a governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) tool for managing and reporting on risk.

Organizations rarely have a single risk tolerance level across the entire business; instead, different business functions and different aspects of security will have varying levels of risk. For example, a mobile gaming software company may have a moderate tolerance for risk with regard to the introduction of new products, a low tolerance for workplace safety risks, and no tolerance for risk for legal and compliance matters. Mature organizations will develop and publish a statement of risk tolerance or appetite that expresses risk tolerance levels throughout the business.

Roles and Responsibilities

Information security governance is most effective when every person in the organization knows what is expected of them. Better organizations develop formal roles and responsibilities so that personnel will have a clearer idea of their part in all matters related to the protection of systems, information, and even themselves.

In the context of organizational structure and behavior, a role is a description of expected activities that employees are obliged to perform as part of their employment. Roles are typically associated with a job title or position title, which is a label assigned to each person that designates their place in the organization. Organizations strive to adhere to more or less standard position titles so that other people in the organization, upon knowing someone’s position title, will have at least a general idea of a person’s role in the organization.

Typical roles include the following:

• IT auditor

• Systems engineer

• Accounts receivable manager

• Individual contributor

Often a position title also includes a person’s rank, which denotes an individual person’s seniority, placement within a command-and-control hierarchy, span of control, or any combination of these. Typical ranks include the following in order of increasing seniority:

• Supervisor

• Manager

• Senior manager

• Director

• Senior director

• Executive director

• Vice president

• Senior vice president

• Executive vice president

• President

• Chief executive officer

• Member, board of directors

• Chairman, board of directors

This should not be considered a complete listing of ranks. Larger organizations also include the modifiers assistant (as in assistant director), general (general manager), and first (first vice president).

A responsibility is a statement of activities that a person is expected to perform. Like roles, responsibilities are typically documented in position descriptions and job descriptions. Typical responsibilities include the following:

• Perform monthly corporate expense reconciliation

• Troubleshoot network faults and develop solutions

• Audit user account terminations and develop exception reports

In addition to specific responsibilities associated with individual position titles, organizations typically also include general responsibilities in all position titles. Examples include the following:

• Understand and conform to information security policy, harassment policy, and other policies

• Understand and conform to code of ethics and behavior

In the context of information security, an organization assigns roles and responsibilities to individuals and groups so that the organization’s security strategy and objectives can be met.

Board of Directors

The board of directors in an organization is a body of people who oversee activities in an organization. Depending on the type of organization, board members may be elected by shareholders or constituents, or they may be appointed. This role can be either paid or voluntary in nature.

Activities performed by the board of directors, as well as directors’ authority, are usually defined by a constitution, bylaws, or external regulation. The board of directors is typically accountable to the owners of the organization or, in the case of a government body, to the electorate.

In many cases, board members have fiduciary duty. This means they are accountable to shareholders or constituents to act in the best interests of the organization with no appearance of impropriety, conflict of interest, or ill-gotten profit as a result of their actions.

In nongovernment organizations, the board of directors is responsible for appointing a chief executive officer (CEO) and possibly other executives. The CEO, then, is accountable to the board of directors and carries out their directives. Board members may also be selected for any of the following reasons:

• Investor representation One or more board members may be appointed by significant investors to give them control over the strategy and direction of the organization.

• Business experience Board members bring outside business management experience, which helps them develop successful business strategies for the organization.

• Access to resources Board members bring business connections, including additional investors, business partners, suppliers, or customers.

Often, one or more board members will have business finance experience in order to bring financial management oversight to the organization. In the case of U.S. public companies, the U.S. Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires board members to form an audit committee; one or more audit committee members are required to have financial management experience. External financial audits and internal audit activities are often accountable directly to the audit committee in order to perform direct oversight of the organization’s financial management activities. As the issue of information security becomes more prevalent in discussions at the executive level, some organizations have added a board member who is technically savvy or have formed an additional committee, often referred to as the Technology Risk Committee.

Boards of directors are generally expected to require that the CEO and other executives implement a corporate governance function to ensure that executive management has an appropriate level of visibility and control over the operations of the organization. Executives are accountable to the board of directors to demonstrate that they are effectively carrying out the board’s strategies.

Many, if not most, organizations are highly dependent upon information technology for their daily operations. As a result, information security is an important topic to boards of directors. Today’s standard of due care for corporate boards requires that they include information security considerations in the strategies they develop and the oversight they exert on the organization. In its publication Cyber-Risk Oversight, the National Association of Corporate Directors has developed five principles about the importance of information security:

• Principle 1: Directors need to understand and approach cybersecurity as an enterprise-wide risk management issue, not just an IT issue.

• Principle 2: Directors should understand the legal implications of cyber risks as they relate to their company’s specific circumstances.

• Principle 3: Boards should have adequate access to cybersecurity expertise, and discussions about cyber-risk management should be given regular and adequate time on board meeting agendas.

• Principle 4: Boards should set the expectation that management will establish an enterprise-wide cyber-risk management framework with adequate staffing and budget.

• Principle 5: Board management discussions about cyber risk should include identification of which risks to avoid, which to accept, and which to mitigate or transfer through insurance, as well as specific plans associated with each approach.

Executive Management

Executive management is responsible for carrying out directives issued by the board of directors. In the context of information security management, this includes ensuring that there are sufficient resources for the organization to implement a security program and to develop and maintain security controls to protect critical assets.

Executive management must ensure that priorities are balanced. In the case of IT and information security, these functions are usually tightly coupled but sometimes in conflict. IT’s primary mission is the development and operation of business-enabling capabilities through the use of information systems, while information security’s mission includes security and compliance. Executive management must ensure that these two sometimes-conflicting missions are successful.

Typical IT and security-related executive position titles include the following:

• Chief information officer (CIO) This is the title of the topmost leader in a larger IT organization.

• Chief technical officer (CTO) This position is usually responsible for an organization’s overall technology strategy. Depending upon the purpose of the organization, this position may be separate from IT.

• Chief information security officer (CISO) This position is responsible for all aspects of data-related security. This usually includes incident management, disaster recovery, vulnerability management, and compliance. This role is usually separate from IT.

To ensure the success of the organization’s information security program, executive management should be involved in three key areas:

• Ratify corporate security policy Security policies that are developed by the information security function should be visibly ratified or endorsed by executive management. This may take different forms, such as formal minuted ratification in a governance meeting, a statement for the need for compliance along with a signature within the body of the security policy document, a separate memorandum to all personnel, or other visible communication to the organization’s rank and file that stresses the importance of, and need for compliance to, the organization’s information security policy.

• Leadership by example With regard to information security policy, executive management should lead by example and not exhibit behavior suggesting they are “above” security policy—or other policies. Executives should not be seen to enjoy special privileges of the nature that suggest that one or more security policies do not apply to them. Instead, their behavior should visibly support security policies that all personnel are expected to comply with.

• Ultimate responsibility Executives are ultimately responsible for all actions carried out by the personnel who report to them. Executives are also ultimately responsible for all outcomes related to organizations to which operations have been outsourced.

Security Steering Committee

Many organizations form a security steering committee, consisting of stakeholders from many (if not all) of the organization’s business units, departments, functions, and principal locations. A steering committee may have a variety of responsibilities, including the following:

• Risk treatment deliberation and recommendation The security steering committee may discuss relevant risks, discuss potential avenues of risk treatment, and develop recommendations for said risk treatment for ratification by executive management.

• Discussion and coordination of IT and security projects The security steering members may discuss various IT and security projects to resolve any resource or scheduling conflicts. They might also discuss potential conflicts between various projects and initiatives and work out solutions.

• Review of recent risk assessments The security steering committee may discuss recent risk assessments in order to develop a common understanding of their results, as well as discuss remediation of findings.

• Discussion of new laws, regulations, and requirements The committee may discuss new laws, regulations, and requirements that may impose changes in the organization’s operations. Committee members can develop high-level strategies that their respective business units or departments can further build out.

• Review of recent security incidents Steering committee members can discuss recent security incidents and their root causes. Often this can result in changes in processes, procedures, or technology changes to reduce the risk and impact of future incidents.

Reading between the lines, the main mission of a security steering committee is to identify and resolve conflicts and to maximize the effectiveness of the security program, as balanced among other business initiatives and priorities.

Business Process and Business Asset Owners

Business process and asset owners are typically nontechnical personnel in management positions in an organization. While they may not be technology experts, in many organizations their business processes are enhanced by information technology in the form of business applications and other capabilities.

Remembering that IT and information security serve the organization and not the other way around, business process and business asset owners are accountable for making business decisions that sometimes impact the use of information technology, the organization’s security posture, or both. A simple example is a decision on whether an individual employee should have access to specific information. While IT or security may have direct control over which personnel have access to what assets, the best decision to make is a business decision by the manager responsible for the process or business asset.

The responsibilities of business process and business asset owners include the following:

• Access grants Asset owners decide whether individuals or groups should be given access to the asset, as well as the level and type of access. Example access types include combinations of read only, read-write, create, and delete.

• Access revocation Asset owners should also decide when individuals or groups no longer require access to an asset, signaling the need to revoke that access.

• Access reviews Asset owners should periodically review access lists to see whether each person and group should continue to have that access. Access reviews may also include access activity reviews to determine whether people who have not accessed assets still require access to them.

• Configuration Asset owners determine the configuration needed for assets and applications, ensuring their proper function and support of applications and business processes.

• Function definition In the case of business applications and services, asset owners determine which functions will be available, how they will work, and how they will support business processes. Typically, this definition is constrained by functional limitations within an application, service, or product.

• Process definition Process owners determine the sequence, steps, roles, and actions carried out in their business processes.

• Physical location Asset owners determine the physical location of their assets. Factors influencing choices of location include physical security, proximity to other assets, proximity to relevant personnel, and data protection and privacy laws.

Often, business and asset owners are nontechnical personnel, so it may be necessary to translate business needs into technical specifications.

Custodial Responsibilities

In many organizations, asset owners are not involved in the day-to-day activities related to the management of their assets, particularly when those assets are information systems and the data stored within them. Instead, somebody in the IT organization (or several people in IT) acts as a proxy for asset owners and makes access grants and other decisions on their behalf. While this is a common practice, it is often carried too far, resulting in the asset owner being virtually uninvolved and uninformed. Instead, asset owners should be aware of, and periodically review, activities carried out by people, groups, and departments making decisions on their behalf.

The most typical arrangement is that people in IT make access decisions on behalf of asset owners. Except in cases where there is a close partnership between these IT personnel and asset owners, these IT personnel often do not adequately understand the business nature of assets or the implications when certain people are given access to them. Most often, far too many personnel have access to assets, usually with higher privileges than necessary.

Chief Information Security Officer

The CISO is the highest-ranking security person in an organization. A CISO will develop business-aligned security strategies that support present and future business initiatives and be responsible for the development and operation of the organization’s information risk program, the development and implementation of security policies, security incident response, and perhaps some operational security functions.

In some organizations, the CISO reports to the chief operating officer (COO) or the CEO, but in some organizations the CISO may report to the CIO, chief legal counsel, or other person in the organization.

Other similar titles with similar responsibilities include the following:

• Chief security officer (CSO) This position generally has the responsibilities of a CISO plus responsibilities for non-information assets such as business equipment and work centers. A CSO often is responsible for workplace safety.

• Chief information risk officer (CIRO) Generally this represents a change of approach to the CISO position, from being protection-based to being risk-based.

• Chief risk officer (CRO) This position is responsible for all aspects of risk including information risk, business risk, compliance risk, and market risk. This role is separate from IT.

Many organizations do not have a CISO but instead have a director or manager of information security who reports further down in the organization chart. There are several possible reasons for organizations not having a CISO, but generally it can be said that the organization does not consider information security as a strategic function. This will hamper the visibility and importance of information security and often results in information security being a tactical function concerned with basic defenses such as firewalls, antivirus, and other tools. In such situations, responsibility for strategy-level information security implicitly lies with some other executive such as the CIO. This type of situation often results in the absence of a security program and the organization’s general lack of awareness of relevant risks, threats, and vulnerabilities.

The one arena where a CISO may not be required is in small to medium-sized organizations where a full-time strategic leader may not be cost effective. In these situations, it is advisable to contract with a virtual CISO (vCISO) to assist with strategy and planning. The benefit of taking this type of approach for organizations that may not require or cannot afford a full-time person is that it allows the organization to benefit from the knowledge of seasoned security professional to assist in driving the information security program forward.

Rank Sets Tone and Gives Power

A glance at the title of the highest-ranking information security position in an organization reveals much about executive management’s opinion of information security in larger organizations. Executive attitudes about security are reflected in the security manager’s title and may resemble the following:

• Security manager Information security is tactical only and often viewed as consisting only of antivirus software and firewalls. The security manager has no visibility into the development of business objectives. Executives consider security as unimportant and based on technology only.

• Security director Information security is important and has moderate decision-making capability but little influence on the business. A director-level person in a larger organization may have little visibility to overall business strategies and little or no access to executive management or the board of directors.

• Vice president Information security is strategic but does not influence business strategy and objectives. The vice president will have some access to executive management and possibly the board of directors.

• CISO/CIRO/CSO/vCISO Information security is strategic, and business objectives are developed with full consideration for risk. The C-level security person has free access to executive management and the board of directors.

Chief Privacy Officer

Some organizations, typically those that manage large amounts of sensitive data on customers, will employ a chief privacy officer (CPO). Some organizations have a CPO because applicable regulations such as HIPAA, the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), and GLBA require it, while others have a CPO because they store massive amounts of personally identifiable information (PII).

The roles of a CPO typically include the safeguarding of PII, as well as ensuring that the organization does not misuse PII at its disposal. Because many organizations with a CPO also have a CISO, the CPO’s duties mainly involve oversight into the organization’s properly handling and use of PII.

The CPO is sometimes seen as a customer advocate, and often this is the role of the CPO, particularly when regulations require a privacy officer.

Software Development

Positions in software development are involved in the design, development, and testing of software applications.

• Systems architect This position is usually responsible for the overall information systems architecture in the organization. This may or may not include overall data architecture and interfaces to external organizations.

• Systems analyst A systems analyst is involved with the design of applications, including changes in an application’s original design. This position may develop technical requirements, program design, and software test plans. In cases where organizations license applications developed by other companies, systems analysts design interfaces to other applications.

• Software engineer/developer This position develops application software. Depending upon the level of experience, people in this position may also design programs or applications. In organizations that utilize purchased application software, developers often create custom interfaces, application customizations, and custom reports.

• Software tester This position tests changes in programs made by software engineers/developers.

While the trend to outsourcing applications has resulted in organizations infrequently developing their own applications from scratch, software development roles persist in organizations. Developers are needed for the creation of customized modules within software platforms, as well as integration tools to connect applications to each other. Still, most organizations have a smaller number of developers than they did a decade or two ago.

Data Management

Positions related to data management are responsible for developing and implementing database designs and for maintaining databases. These positions are concerned with data within applications, as well as data flows between applications.

• Data manager This position is responsible for data architecture and data management in larger organizations.

• Database architect This position develops logical and physical designs of data models for applications. With sufficient experience, this person may also design an organization’s overall data architecture.

• Big data architect This position develops data models and data analytics for large, complex data sets.

• Database administrator (DBA) This position builds and maintains databases designed by the database architect and those databases that are included as part of purchased applications. The DBA monitors databases, tunes them for performance and efficiency, and troubleshoots problems.

• Database analyst This position performs tasks that are junior to the database administrator, carrying out routine data maintenance and monitoring tasks.

• Data scientist This position applies scientific methods, builds processes, and implements systems to extract knowledge or insights from data.

EXAM TIP The roles of data manager, big data architect, database architect, database administrator, database analyst, and data scientist are distinct from data owners. The former are IT department roles for managing data models and data technology, whereas the latter role governs the business use of, and access to, data in information systems.

Network Management

Positions in network management are responsible for designing, building, monitoring, and maintaining voice and data communications networks, including connections to outside business partners and the Internet.

• Network architect This position designs data and voice networks and designs changes and upgrades to networks as needed to meet new organization objectives.

• Network engineer This position implements, configures, and maintains network devices such as routers, switches, firewalls, and gateways.

• Network administrator This position performs routine tasks in the network such as making configuration changes and monitoring event logs.

• Telecom engineer Positions in this role work with telecommunications technologies such as telecomm services, data circuits, phone systems, conferencing systems, and voice-mail systems.

Systems Management

Positions in systems management are responsible for architecture, design, building, and maintenance of servers and operating systems. This may include desktop operating systems as well. Personnel in these positions also design and manage virtualized environments as well as microsegmentation.

• Systems architect This position is responsible for the overall architecture of systems (usually servers), in terms of both the internal architecture of a system and the relationship between systems. This position is usually also responsible for the design of services such as authentication, e-mail, and time synchronization.

• Systems engineer This position is responsible for designing, building, and maintaining servers and server operating systems.

• Storage engineer This position is responsible for designing, building, and maintaining storage subsystems.

• Systems administrator This position is responsible for performing maintenance and configuration operations on systems.

Operations

Positions in operations are responsible for day-to-day operational tasks that may include networks, servers, databases, and applications.

• Operations manager This position is responsible for overall operations that are carried out by others. Responsibilities will include establishing operations and shift schedules.

• Operations analyst This position may be responsible for developing operational procedures; examining the health of networks, systems, and databases; setting and monitoring the operations schedule; and maintaining operations records.

• Controls analyst This position is responsible for monitoring batch jobs, data entry work, and other tasks to make sure they are operating correctly.

• Systems operator This position is responsible for monitoring systems and networks, performing backup tasks, running batch jobs, printing reports, and other operational tasks.

• Data entry This position is responsible for keying batches of data from hard copy or other sources.

• Media manager This position is responsible for maintaining and tracking the use and whereabouts of backup tapes and other media.

Security Operations

Positions in security operations are responsible for designing, building, and monitoring security systems and security controls to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information systems.

• Security architect This position is responsible for the design of security controls and systems such as authentication, audit logging, intrusion detection systems, intrusion prevention systems, and firewalls.

• Security engineer This position is responsible for designing, building, and maintaining security services and systems that are designed by the security architect.

• Security analyst This position is responsible for examining logs from firewalls and intrusion detection systems, as well as audit logs from systems and applications. This position may also be responsible for issuing security advisories to others in IT.

• Access administrator This position is responsible for accepting approved requests for user access management changes and performing the necessary changes at the network, system, database, or application level. Often, this position is carried out by personnel in network and systems management functions; only in larger organizations is user account management performed in security or even in a separate user access department.

Security Audit

Positions in security audit are responsible for examining process design and for verifying the effectiveness of security controls.

• Security audit manager This position is responsible for audit operations, as well as scheduling and managing audits.

• Security auditor This position is responsible for performing internal audits of IT controls to ensure that they are being operated properly.

CAUTION Security audit positions need to be carefully placed in the organization so that people in this role can be objective and independent from the departments, processes, and systems they audit.

Service Desk

Positions at the service desk are responsible for providing frontline support services to IT and IT’s customers.

• Service desk manager This position serves as a liaison between end users and the IT service desk department.

• Service desk analyst This position is responsible for providing frontline user support services to personnel in the organization. This is sometimes known as a help-desk analyst.

• Technical support analyst This position is responsible for providing technical support services to other IT personnel and perhaps also to IT customers.

Quality Assurance

Positions in quality assurance are responsible for evaluating IT systems and processes to confirm their accuracy and effectiveness.

• QA manager This position is responsible for facilitating quality improvement activities throughout the IT organization.

• QC manager This position is responsible for testing IT systems and applications to confirm whether they are free of defects.

Other Roles

Other roles in IT organizations include the following:

• Vendor manager This position is responsible for maintaining business relationships with external vendors, measuring their performance, and handling business issues.

• Project manager This position is responsible for creating project plans and managing IT projects.

General Staff

The rank and file in an organization may or may not have explicit information security responsibilities, determined in part by executive management’s understanding of the broad capabilities of information systems and the personnel who use them and determined also in executives’ understanding of the human role in information security.

Typically, general staff security-related responsibilities include the following:

• Understanding and compliance to organization security policy

• Acceptable use of organization assets, including information systems and information

• Proper judgment, including proper responses to people who request information or request that staff members perform specific functions (the primary impetus for this is the phenomenon of social engineering and its use as an attack vector)

• Reporting of security-related matters and incidents to management

Better organizations have standard language in job descriptions that specify general responsibilities for the protection of assets.

Monitoring Responsibilities

The practice of monitoring responsibilities helps an organization confirm that the correct jobs are being carried out in the right way. There is no single approach, but several activities provide information to management, including the following:

• Controls and internal audit Developing one or more controls around specific responsibilities gives management greater control over key activities. Internal audit of controls provides objective analysis on control effectiveness.

• Metrics and reporting Developing metrics for repeated activities helps management better understand work output.

• Work measurement This is a more structured activity used to carefully measure repeated tasks to better understand the volume of work performed.

• Performance evaluation This is a traditional qualitative method used to evaluate employee performance.

• 360 feedback Soliciting structured feedback from peers, subordinates, and management helps subjects and management better understand characteristics related to specific responsibilities.

• Position benchmarking This technique is used by organizations that want to compare job titles and people holding them with those in other organizations. There is no direct monitoring of responsibilities, but instead this helps an organization determine whether they have the right positions in place and that they are staffed by competent and qualified personnel. This may be useful for organizations that are troubleshooting employee performance.

Information Security Governance Metrics

Metrics are the means through which management can measure key processes and know whether their strategies are working. Metrics are used in many operational processes, but in this section, metrics as related to security governance are the emphasis. In other words, there is a distinction between tactical IT security metrics and those that reveal the state of the overall security program. The two, however, are often related, as discussed in the sidebar “Return on Security Investment.”

Security metrics are often used to observe technical IT security controls and processes and to know whether they are operating properly. This helps management better understand the impact of past decisions and can help drive future decisions. Examples of technical metrics include the following:

• Firewall metrics Number and types of rules triggered

• Intrusion detection/prevention system (IDPS) metrics Number and types of incidents detected or blocked, and targeted systems

• Anti-malware metrics Number and types of malware blocked, and targeted systems

• Other security system metrics Measurements from data loss prevention (DLP) systems, web content filtering systems, cloud access security broker (CASB) systems, and so on

While useful, these metrics do not address the bigger picture of the effectiveness or alignment of an organization’s overall security program. They do not answer key questions that boards of directors and executive management often ask, such as the following:

• How much security is enough?

• How should security resources be invested and applied?

• What is the potential impact of a threat event?

These and other business-related questions can be addressed through the right metrics, addressed in the remainder of this section.

Security strategists sometimes think about metrics in simple categorization, including the following:

• Key risk indicators (KRIs) These are metrics associated with the measurement of risk.

• Key goal indicators (KGIs) These metrics portray the attainment of strategic goals.

• Key performance indicators (KPIs) These metrics are used to show efficiency or effectiveness of security-related activities.

Effective Metrics

For metrics to be effective, they need to be measurable. A common way to ensure the quality and effectiveness of a metric is to use the SMART method. A metric that is SMART is

• Specific

• Measurable

• Attainable

• Relevant

• Timely

Additional considerations for good metrics, according to Risk Metrics That Influence Business Decisions by Paul Proctor (Gartner, Inc., 2016), include the following:

• Leading indicator Does the metric help management to predict future risk?

• Causal relationship Does the metric have a defensible causal relationship to a business impact, where a change in the metric compels someone to act?

• Influence Has the metric influenced decision-making (or will it)?

You can find more information about the development of metrics in NIST Special Publication 800-55 Revision 1, Performance Measurement Guide for Information Security, available at www.nist.gov.

Strategic Alignment

For a security program to be successful, it must align to the organization’s mission, strategy, and goals and objectives. A security program strategy and objectives should contain statements that can be translated into key measurements—the key performance and risk metrics of the program.

Here is an example: The organization CareerSearchCo, which is in the online career search and recruiting business, has the following as its mission statement:

Be the best marketplace for job seekers and recruiters

Here are its most recent strategic objectives:

Integrate with leading business social network LinkedIn

Develop an API to facilitate long-term transformation into a leading career and recruiting platform

To meet these objectives, CareerSearchCo has developed a security strategy that includes the following:

Ensure Internet-facing applications are secure through developer training and application vulnerability testing

Security and metrics would then include these:

Percentage of software developers not yet trained

Number of critical vulnerabilities identified

Time to remediate critical and high vulnerabilities

Based on these criteria, these metrics are all measurable, they align to the security strategy, and they are all leading indicators. The higher these metrics, the more likely a breach would occur that would damage CareerSearchCo’s reputation and ability to earn new business contracts from large corporations.

Risk Management

Effective risk management is the culmination of the highest-order activities in an information security program; these include risk analyses, the use of a risk ledger, formal risk treatment, and adjustments to the suite of security controls.

While it is difficult to effectively and objectively measure the success of a risk management program, it is possible to take indirect measurements—much like measuring the shadow of a tree to gauge its height. Thus, the best indicators of a successful risk management program would be improving trends in metrics involved with the following:

• Reduction in the number of security incidents

• Reduction in the impact of security incidents

• Reduction in the time to remediate security incidents

• Reduction in the time to remediate vulnerabilities

• Reduction in the number of new unmitigated risks

Regarding the previous mention of the reduction of security incidents, a security program improving its maturity from low levels should first expect to see the number of incidents increase. This would be not because of lapses in security controls but because of the development of—and improvements in—mechanisms used to detect and report security incidents.

Similarly, as a security program is improved and matures over time, the number of new risks will, at first, increase and then later decrease.

Performance Measurement

Metrics on the performance of information security provide measures of timeliness and effectiveness. Generally speaking, performance measurement metrics provide a view of tactical security processes and activities. As discussed earlier in this section, performance measurements are often the operational metrics that need to be transformed into executive-level metrics for those audiences.

Performance measurement metrics can include any of the following:

• Time to detect security incidents

• Time to remediate security incidents

• Time to provision user accounts

• Time to deprovision user accounts

• Time to discover vulnerabilities

• Time to remediate vulnerabilities

Nearly every operational activity that is security-related and measurable is a candidate for performance metrics.

Convergence

Larger organizations with multiple business units, geographic locations, or security functions (often as a result of mergers and acquisitions) may be experiencing issues related to overlapping or underlapping coverage or activities. For instance, an organization that recently acquired another company may have some duplication of effort in the asset management and risk management functions. In another example, local security personnel in a large, distributed organization may be performing security functions that are also being performed on their behalf by other personnel at headquarters.

Metrics in the category of convergence will be highly individualized, based on specific circumstances in an organization. Some of the categories of metrics may include the following:

• Gaps in asset coverage

• Overlaps in asset coverage

• Consolidation of licenses for security tools

• Gaps or overlaps in skills, responsibilities, or coverage

Value Delivery

Metrics on value delivery focus on the long-term reduction in costs, in proportion to other measures. Examples of value delivery metrics include the following:

• Controls used (seldom used controls may be candidates for removal)

• Percentage of controls that are effective (ineffective controls consume additional resources in audit, analysis, and remediation activities)

• Program costs per asset population or asset value

• Program costs per employee population

• Program costs per revenue

Organizations are cautioned against using only value delivery metrics—doing so will risk the security program spiraling down to nothing since a program that costs nothing will produce the best possible metric.

Resource Management

Resource management metrics are similar to value delivery metrics; both convey an efficient use of resources in an organization’s information security program. But because the emphasis here is program efficiency, these are areas where resource management metrics may be developed:

• Standardization of security-related processes—because consistency drives costs down

• Security involvement in every procurement and acquisition project

• Percentage of assets protected by security controls

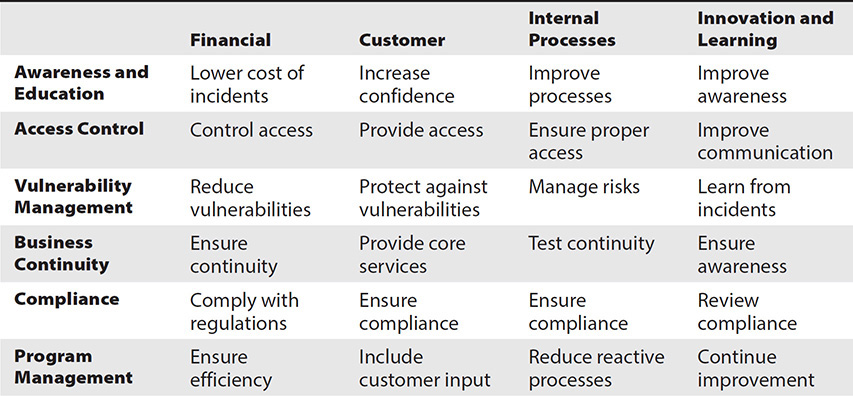

The Security Balanced Scorecard

The balanced scorecard (BSC) is a management tool that is used to measure the performance and effectiveness of an organization. The balanced scorecard is used to determine how well an organization can fulfill its mission and strategic objectives and how well it is aligned with overall organizational objectives.

In the balanced scorecard, management defines key measurements in each of four perspectives:

• Financial Key financial items measured include the cost of strategic initiatives, support costs of key applications, and capital investment.

• Customer Key measurements include the satisfaction rate with various customer-facing aspects of the organization.

• Internal processes Measurements of key activities include the number of projects and the effectiveness of key internal workings of the organization.

• Innovation and learning Human-oriented measurements include turnover, illness, internal promotions, and training.

Each organization’s balanced scorecard will represent a unique set of measurements that reflects the organization’s type of business, business model, and style of management.

The balanced scorecard should be used to measure overall organizational effectiveness and progress. A similar scorecard, the security balanced scorecard, can be used to specifically measure security organization performance and results.

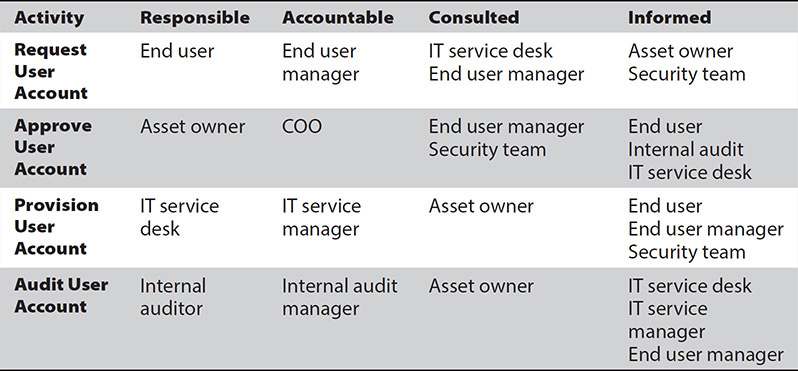

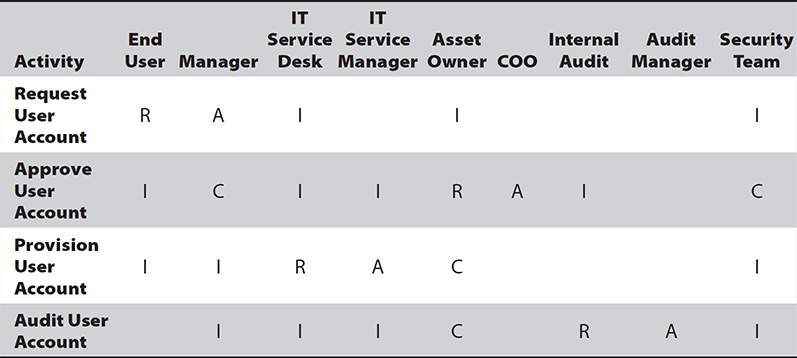

Like the balanced scorecard, the security balanced scorecard (security-BSC) has the same four perspectives, mapped to key activities as depicted in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1 Security Balanced Scorecard Domains

The security balanced scorecard should flow directly out of the organization’s overall balanced scorecard and its IT balanced scorecard (IT-BSC). This will ensure that security will align itself with corporate objectives. While the perspectives between the overall BSC and the security BSC vary, the approach for each is similar, and the results for the security-BSC can “roll up” to the organization’s overall BSC.

Business Model for Information Security

Developed by ISACA in 2009, the Business Model for Information Security (BMIS) is a guide for business-aligned, risk-based security governance. The use of BMIS helps security leadership ensure that the organization’s security program continues to address emerging threats, developing regulations, and changing business needs.

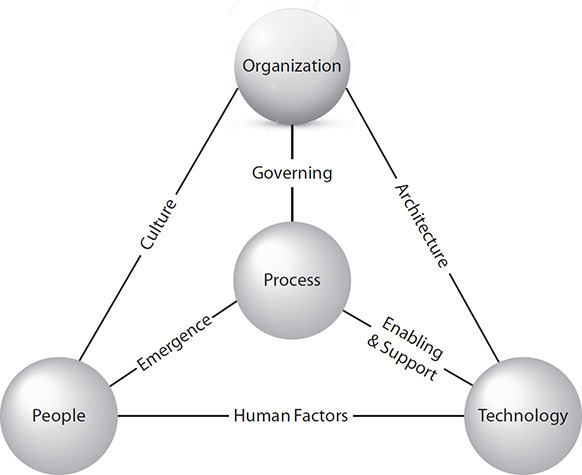

BMIS is a three-dimensional, three-sided pyramid, depicted in Figure 2-2. The three foundation elements of the pyramid are people, process, and technology, while the apex element of the pyramid is the organization.

Figure 2-2 The BMIS model (Adapted from The Business Model for Information Security, ISACA)

The BMIS model includes the three traditional elements found in IT, which are people, process, and technology, and adds a fourth element, organization. The elements are connected by dynamic interconnections (DIs), which are culture, governing, architecture, emergence, enabling and support, and human factors. The elements and dynamic interconnections are described in more detail in the following sections.

BMIS is described fully in the document The Business Model for Information Security from ISACA, available at https://www.isaca.org/bmis.

The BMIS is derived from the Systemic Security Management Framework, developed by the University of Southern California (USC) Marshall School of Business in 2006.

BMIS Elements and Dynamic Interconnections

The elements and dynamic interconnections are the major pieces of the BMIS model and are described in detail in this section.

Organization The organization element in the BMIS model makes the model unique. Most other models focus on people, process, and technology—or other aspects of an organization without considering the organization itself.

BMIS defines the organization as “a network of people interacting, using processes to channel this interaction.” This is not unlike the executive management perspective that views the organization as a set of elements that act together to accomplish strategic objectives. The organization includes not only the permanent staff but also temporary workers, contractors, and consultants, as well as third-party organizations that also play roles in helping the organization achieve its objectives.

Organizations are formally structured through organization charts, command-and-control hierarchy, policies, processes, and procedures.

But organizations also have their informal, undocumented organization, which can be viewed like additional synapses that connect people or groups across the organization in ways not intended, nonetheless helping the organization achieve its objectives. This is often seen in distributed organizations, where expediency and pragmatism often rule over policy and process, particularly in locations farther away from corporate headquarters.

People The people element in the BMIS model represents all of the people in an organization, whether full-time employees or temporary workers, contractors, or consultants. Further, as an organization outsources its operations to other organizations, the people in those organizations are also part of the people in the people element in BMIS.

Like the other elements in the BMIS model, people cannot be studied by themselves but instead must be considered alongside the other elements of process, technology, and organization.

Process The process element in the BMIS model represents the formal structure of all defined activities in the organization, which together help the organization achieve its strategic objectives. Process defines practices and procedures that describe how activities are to be carried out.

ISACA’s Risk IT framework defines an effective process as a reliable and repetitive collection of activities and controls to perform a certain task. Processes take input from one or more sources (including other processes), manipulate the input, utilize resources according to the policies, and produce output (including output to other processes). Processes should have clear business reasons for existing, accountable owners, clear roles and responsibilities around the execution of each key activity, and the means to undertake and measure performance.

Individual processes have the attribute of maturity, which qualitatively describes how well the process is designed, as well as how it is measured and improved over time.

Technology The technology element in the BMIS model represents all of the systems, applications, and tools used by practitioners in an organization. Technology is a powerful enabler of an organization’s processes and of its strategic objectives, although unless tamed with process and by people, technology by itself can accomplish little for an organization.

As the BMIS model illustrates, technology in an organization does not run by itself. Instead, people and processes are critical to any successful use of technology. Technology can be viewed as a process enabler and as a force multiplier, helping the organization accomplish more work in less time, for less cost, and with greater accuracy.

Culture The culture DI connects the organization and people elements. Culture as part of a governance model makes BMIS unique, as most other models do not consider culture with strategic importance. BMIS defines culture as “a pattern of behaviors, beliefs, assumptions, attitudes, and ways of doing things.”

Culture is the catalyst that drives behavior, with as much or more influence than formal directives such as policies and standards. Culture determines the degree to which personnel strive to conform to security policy and contribute to the protection of critical assets or whether they behave contrary to policy and put critical assets in jeopardy.

An organization’s culture is considered one of the most critical factors in the success or failure of an information security program. By its nature, culture cannot be legislated or controlled directly, but instead it reflects the attitudes, habits, and customs adopted by the people in the organization.

The civil culture of the community in which the organization resides plays a large role in shaping the organization’s culture. For this reason, establishing a single culture in an organization with many regional or global locations is not feasible.

Of utmost importance to the security strategist is the development of a productive security culture. Like other aspects of organizational culture, a desired security culture cannot simply be legislated through policy but must be carefully curated and grown. Steps to create a favorable security culture include the following:

• Involve personnel in discussions about the protection of critical assets.

• Executive leadership must lead by example and follow all policies.

• Include security responsibilities in all job descriptions.

• Include security factors in employees’ compensation—for example, merit increases and bonuses.

• Link the protection of critical assets to the long-term success of the organization.

• Integrate messages related to the protection of assets, and other aspects of the information security program, into existing communications such as newsletters.

• Incorporate “secure by design” into key business processes so that security is part of the organization’s routine activities.

• Reward and recognize desired behavior; similarly, admonish undesired behavior privately.

Changing an organization’s security culture cannot be accomplished overnight, and it cannot be forced. Instead, every individual needs to understand consistent messaging that reiterates the importance of sound security practices.

For individuals and teams who don’t “get it,” the organization must be willing to take remedial action, not unlike that which would be undertaken when other undesired behavior is witnessed. Individuals who are teachable need to be coached on desired behavior. Those who prove to be unteachable may be dealt with in other ways.

Governing The governing DI connects the organization and process elements. Per the definition from ISACA, “governance is the set of responsibilities and practices exercised by the board and executive management with the goal of providing strategic direction, ensuring that objectives are achieved, ascertaining that risks are managed appropriately and verifying that the enterprise’s resources are used responsibly.”

This means that processes are influenced, even controlled, by the organization’s mission, strategic objectives, and other factors. In other words, the organization’s processes must support the organization’s mission and strategic objectives. When they don’t, governance is used to change them until they are.

The tools used in governing include the following:

• Policies

• Standards

• Guidelines

• Process documentation

• Resource allocation

• Compliance

These tools are used by management to exert control over the development and operation of business processes, ensuring desired outcomes.

Communications is vital in the governing DI. Information flows down from management in the form of directives to influence change in business processes.

When the governing DI fails, processes no longer align with organization objectives and take on a life of their own.

Architecture The architecture DI connects the organization and technology elements. The purpose of the DI between organization and technology signifies the need for the use of technology to be planned, orderly, and purposeful.

The definition of architecture, according to ISO/IEC 42010, “Systems and software engineering — Architecture description,” is fundamental concepts or properties of a system in its environment embodied in its elements, in its relationships, and in the principles of its design and evolution. The practice of architecture ensures the following:

• Alignment Applications and infrastructure will support the organization’s mission and objectives.

• Consistency Similar or even identical practices and solutions will be employed throughout the IT environment.

• Efficiency The IT organization as well as its environment can be built and operated more efficiently, mainly through consistent designs and practices.

• Low cost With a more consistent approach, acquisition and support costs can be reduced, through economy of scale and less waste.

• Resilience Purposeful architectures and designs with greater resilience can be realized.

• Flexibility Architectures must have the desired degree of flexibility to accommodate changing business needs and external factors such as regulations and market conditions.

• Scalability Sound architectures are not rigid in their size but can be made larger or smaller to accommodate various business needs, such as growth in revenue, various size branch offices, and larger data sets.

• Security With the development of security policies, standards, and guidelines, the principle of “secure by design” is more certain in future applications and systems.

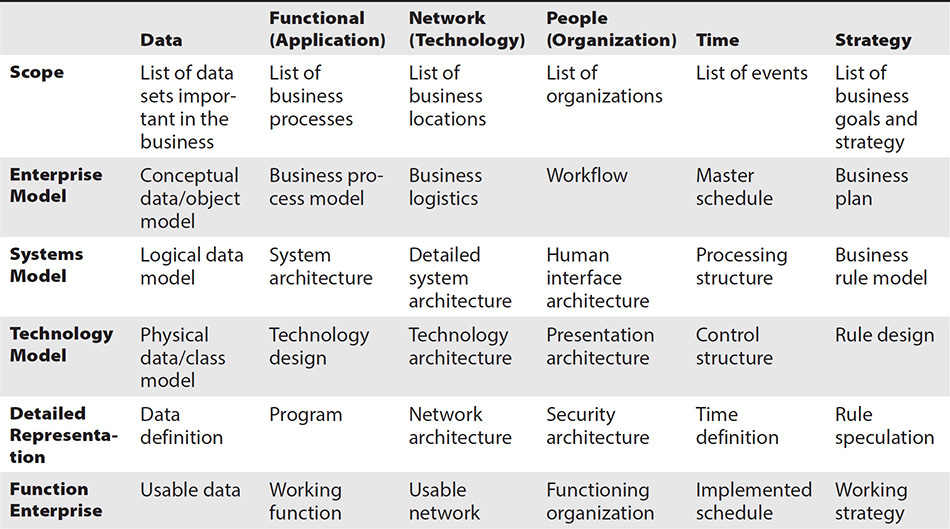

The Zachman framework

The Zachman enterprise architecture framework, established in the late 1980s, continues to be the dominant enterprise architecture standard today. Zachman likens IT enterprise architecture to the construction and maintenance of an office building: at a high (abstract, not number of floors) level, the office building performs functions such as containing office space. As you look into increasing levels of detail in the building, you encounter various trades (steel, concrete, drywall, electrical, plumbing, telephone, fire control, elevators, and so on), each of which has its own specifications, standards, regulations, construction and maintenance methods, and so on.

In the Zachman architecture model, IT systems and environments are described at a high, functional level and then, in increasing detail, encompassing systems, databases, applications, networks, and so on. The Zachman framework is illustrated in Table 2-2.

Table 2-2 The Zachman Framework Shows IT Systems in Increasing Levels of Detail

While the Zachman model allows an organization to peer into cross sections of an IT environment that supports business processes, the model does not convey the relationships between IT systems. Data flow diagrams are used instead to depict information flows.

Data flow diagrams (DFDs) are frequently used to illustrate the flow of information between IT applications. Like the Zachman model, a DFD can begin as a high-level diagram, where the labels of information flows are expressed in business terms. Written specifications about each flow can accompany the DFD; these specifications would describe the flow in increasing levels of detail, all the way to field lengths and communication protocol settings.

Similar to Zachman, DFDs permit nontechnical business executives to easily understand the various IT applications and the relationships between them. Figure 2-3 shows a typical DFD.

Figure 2-3 A typical DFD shows the relationship between IT applications.

Emergence The emergence DI connects the people and process elements. The purpose of the emergence DI is to bring focus to the way people perform their work. Emergence is seen as the arising of new opportunities for organizations, new processes, new practices, and new ways of doing things. Emergence can be a result of people learning how to do things better, faster, more accurately, or with less effort.

Emergence can be seen as a two-edged sword. The creativity and ingenuity of people can lead to better ways of doing things, but on the other hand, this can lead to inconsistent results including errors or lapses in product or service quality.

Organizations that want to reduce work output deviation caused by emergence have a few potential remedies.

• Increase automation Removing some of the human factors from a process through automation can yield more consistent outcomes.

• Enact controls Putting key controls in place can help management focus on factors responsible for outcome deviation. This can lead to process improvements later.

• Increase process maturity Organizations can enact changes in business process to increase the maturity of those processes. Examples include adding key measurements or producing richer log data so that processes can be better understood and improved over time.

Organizations need to understand which activities can benefit from automation and which require human judgment that cannot be programmed into a computer. This sometimes involves human factors because there may be times when people prefer to interact with a person versus a machine, even if the machine is faster or more accurate. Automation does not always equal improvement to all parties concerned.

Enabling and Support The enabling and support DI connects the process and technology elements. The purpose of the enabling and support DI is the enablement and support of business processes by technology. Put another way, information technology makes business processes faster and more accurate than if they were performed manually.

In an appropriate relationship between business processes and technology, the structure of business processes determines how technology will support them. Unfortunately, many organizations compromise their business processes by having capabilities in poorly selected or poorly designed technology determine how business processes operate. While it is not always feasible for technology to support every whim and nuance in a business process, many organizations take the other extreme by selecting technology that does not align with their business processes or the organization’s mission and objectives and changing their processes to match capabilities provided by technology. This level of compromise is detrimental to the organization.