CHAPTER 4

THE BUSINESS CASE FOR DECENCY

“PhD in Leadership. Short course:

Make a short list of all things done to you that you abhorred.

Don’t do them to others. Ever.

Make another list of things done to you that you loved.

Do them to others. Always.”

—TOM PETERS

Leaders acknowledge that, by every measure, human assets represent the critical difference between corporate success and failure. Now more than ever, responsible leaders understand the connection between decency and employee retention and engagement. The best leaders know that a deterioration of civility leads to the decline of employment retention and engagement.

Developing and nurturing talent is a significant driver of employee engagement, which in turn is the key to the outcomes all businesses seek: revenue, profitability, quality, innovation, reputation, and customer loyalty. Talent shortage is not just a demographic issue. It is, leaders would agree, a matter of how well a pattern of decency is embedded in the corporate culture.

Every business assures us that its greatest asset is its employees. It’s pretty callous to refer to human beings as assets in any case. This assurance is often little more than lip service. One would hope businesses would do everything in their power to treat their employees well. In fact, as we see every day, a great deal of daylight can exist between what businesses say they value and what, by their behavior, they actually value.

CNN Money reported that 84 percent of America’s workers were unhappy with their current positions.1 Mercer’s “What’s Working” survey found that one in three US employees are serious about leaving their current jobs.2

Gratitude, focusing on positive experiences, exercising, and random acts of kindness are all ways to change the pattern through which our brain views work. This conclusion is the thrust of “The Price of Incivility: Lack of Respect Hurts Morale and the Bottom Line,” published in the Harvard Business Review.3 The research, polling managers and employees in 17 industries, revealed the high price organizations pay for workers who have been on the receiving end of indecency at work. Specifically, the research concluded that:

• 80% lost work time worrying about the incident.

• 78% said their commitment to the organization declined.

• 66% said their performance declined.

• 63% lost work time avoiding the offender.

• 48% intentionally decreased their work effort.

• 47% intentionally decreased the time spent at work.

• 38% intentionally decreased the quality of their work.

• 25% admitted taking their frustration out on customers.

• 12% said that they left their jobs because of the uncivil treatment.

The Cost of Turnover

Employee retention is one benefit of high employee engagement. Experience shows that when engagement goes down, employee turnover goes up. It’s also well understood that employee turnover is expensive, but less well understood is how expensive. A recent report by Forbes magazine estimates that employee turnover alone cost US companies $160 billion in 2017 in recruitment, administration, lost productivity, and retraining.4

Some turnover is necessary for healthy organizations. For employees, turnover can represent opportunity. Improving economic conditions make it easier for employees to switch jobs and pursue their career goals. It is well known in organizational development that employees generally don’t quit their companies, they quit their supervisors. According to the Washington Post, when employees quit, of the seven most common reasons given for quitting, six have to do with the behavior of their direct managers:

• Isolated or disconnected manager

• Lack of feeling supported by their manager

• Disrespect from their manager

• Confusing priorities and expectations from management

• Low or no growth opportunities

• Inadequate coaching

• Lack of feedback from their manager5

Decent Benefits

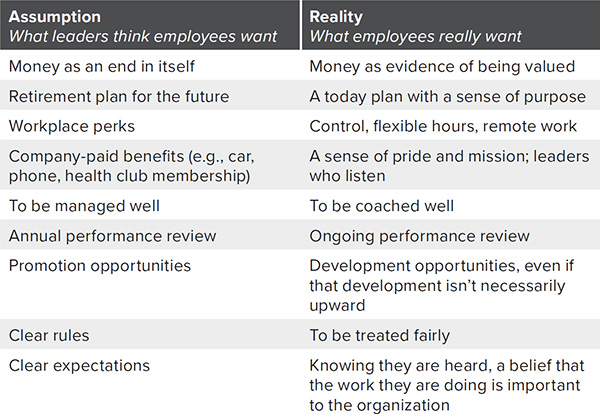

Leaders are often uncertain about what their employees want. Or, worse, they make assumptions. Invariably, the default hypothesis is that what employees want most are material benefits: more money, more vacation, better parking, better food in the cafeteria, more perks. The assumption continues that the more material benefits employees have, the happier they will be and the less they will want to quit.

Haven’t companies learned that the basis of customer satisfaction is listening to their customers? Why would they forget that lesson when it comes to engaging with their employees? So, the first step is to get leaders to ask their employees: What would inspire you to be more committed? More engaged? More aligned with the mission?

Research shows that there is a big disconnect between what leaders think employees want and what employees say they want.6 Had leaders asked fewer questions (most of these engagement studies involve asking employees more than a hundred questions), then listened to and taken action on the answers the questions produced, leaders would have learned that while material benefits are important, there are other issues that are far more important. The worst part is, when employees are asked the same questions repeatedly yet all their answers are still ignored, they learn to have little expectation that any meaningful change will occur. Consider this side-by-side comparison:

Let’s be clear. Inadequate material benefits, such as a salary not commensurate with experience or fewer benefits than prevailing industry norms, will certainly lead to increased turnover. It’s the reciprocal assumption—that more material benefits over a certain point will lead to more engagement—that is not supported by research.

The reality is that what employees are truly looking for goes beyond material benefits or perks that can be counted on a spreadsheet. Rather, employees are looking for work that provides a sense of meaning and personal satisfaction in working conditions that can be described by the word “decent.”

Most relevant research supports this view. “Many researchers who have studied retention agree on what engages or satisfies people and therefore influences them to stay: meaningful and challenging work, a chance to learn and grow, fair and competitive compensation, great coworkers, recognition, respect, and a good boss,” write Beverly Kaye and Sharon Jordan-Evans in their book Love ’Em or Lose ’Em: Getting Good People to Stay. It’s no longer enough to simply throw “material” things at employees and expect them to remain engaged.

Employee Needs Are in Flux

It’s also important to note that what motivates employees today may change tomorrow. The needs of employees are always in flux. This fact challenges managers to find new ways to motivate, inspire, and reward their people. Otherwise, employees will keep jumping from job to job in a quest to satisfy the need they have for meaning at work. A culture of decencies works to get ahead of the turnover curve. Such a culture encourages companies to demonstrate to both potential and active employees that they can realistically expect to find:

A connection to—even passion in—their work. Employee engagement and retention are closely linked; workers who feel passionate about their jobs are less likely to leave. “Passion for work means that people find what they do to be so exciting that it sometimes doesn’t even feel like work—so exciting that it brings exhilaration, a ‘high,’ ” write Beverly Kaye and Sharon Jordan-Evans. “Granted, even those who have this passion seldom have it every day, but they do know that feeling, and they know when they lose it.”

Respect for their contributions. Many managers feel that if they don’t exhibit some sort of command-control, they won’t get the most from their employees. However, as evidenced by the growing practice of servant leadership, hierarchical models are becoming increasingly outdated and rejected by a millennial workforce. Providing employees with a “seat at the table” and an opportunity to share their opinions without fear is a critical way to show respect, driving the alignment between what managers want and what employees need. Showing trust, understanding, and fairness inspires employees to reflect those qualities back, ultimately improving productivity and creating a more dedicated workforce.

A Form of “Goodwill Banking”

All of this demonstrates that the role of decency is more than a desirable artifact of an organizational culture when business conditions make it affordable. It is not a compromise to productivity or quality. It does not impede competitiveness. Decency is a form of “goodwill banking,” an accelerant to innovation and value-driven excellence. Finally, decencies can help inoculate the corporate culture against the kinds of opportunism and expediency that invite ethical lapses and corporate crises.

How do decencies work? Let’s consider the hiring process. For the job seeker, what are the indicators of corporate decency? The reception area often determines the prospective employee’s first impression of the company. How is the visitor welcomed? As a valued source of expertise for the organization or as another bother? Is the receptionist friendly or distracted? Is there a physical barrier between the visitor and the receptionist? Does he or she multitask to a fault?

“Look for the telltale signs,” author John Cowan writes. Character always reveals itself. He goes on to suggest that “we can be true to our values both at home and at work . . . the more humanely we treat one another, the better we will be as people, and the better we will be at doing our life’s work.” Decencies, to be culturally impactful, need to be actionable, tangible, practical, affordable, replicable, and sustainable. Decencies are a cultural gift. They create stories—and stories travel, even faster than photocopied values statements.

There are other signs of cultural decency, too. How prepared are the hiring authorities? Are they focused? Do they take steps to demonstrate the importance of the interview by, say, turning off their phones or otherwise seeing to it that the meeting is uninterrupted? Do they demonstrate a willingness to not just take, but to give, information? Is the visitor provided the opportunity to ask questions, and if so, are those questions answered specifically? Is there a prompt and smooth handoff to a second interviewer, if there is one? At the end, is there clear commitment to next steps, and if so, are the commitments honored? Is the visitor courteously escorted back to the reception area?

Finally, enlightened leaders understand the benefits of treating unsuccessful applicants decently. Quite apart from treating people with dignity and respect, it must be remembered that rejected applicants add another voice to the conversations that determine a company’s reputation and brand. One leader who understood this truth was Herb Kohl, the son of the founder of Kohl’s, with 1,158 locations, currently one of the largest department store chains in the United States. Founded in 1927 by Polish immigrant Maxwell Kohl, the chain developed a reputation of treating employees well. “Every employee is going to have a last day,” says Ryan Festerling, former vice president of human resources at Kohl’s. “You can’t ask people to be brand ambassadors if you don’t treat them well on the way out.”

A recent “Preoccupations” feature article in the New York Times was titled, “Be Nice to Job Seekers (They’re Shoppers, Too).”7 When the way an organization interacts with job candidates is devoid of basic professional courtesies, selection quality suffers, retention goes down, and hiring costs go up. The interactions decency engenders are not costly: prompt responses to phone calls and e-mails, personalized attention, and frequent “keep in the loop” communications.

In our new world, candidates’ correspondence to companies is rarely acknowledged. Calls are seldom returned. Status updates are not routinely provided. Rejection decisions are not consistently communicated. All this combines to create the job-search black hole. A business can lose sight that there are real people behind all those résumés, and how the company treats those people says a lot about it, its brand, and its values.

This may sound like recruitment best practices, but the reality is that many employers become so transactional in their hiring that some of these decencies are forgotten. The unfortunate reality of hiring is that there will always be more people rejected than hired. To the extent companies can moderate the blow of rejection, they may reap unexpected benefits.

A Stanford University case study revealed that a few employers get this concept.8 These companies recognize that employment candidates are also or might become customers. At Nabisco, for example, a manager declared that his company responds to every résumé. When asked why, he said, “Because everyone eats cookies.”

Human Touch Matters

Consultants and business journals are not alone in highlighting the essential mandate of the human factor. Robert Reich, in his book The Future of Success, writes: “Human touch matters: in restaurants, banks, medical care, hotels and spas. Personal attention is not a frill, it’s a necessity.” Reich, the former US Secretary of Labor, sums it up in two words: “Compassionate Capitalism.”

When Herb Baum, ex-CEO of Dial Corporation, routinely sat down with small employee groups for “Hot Dogs with Herb,” he understood the power of decency. When the leadership at W. L. Gore (Gore-Tex) created and sustained a failure-tolerant innovation culture, they understood the power of decency. When Doug Conant, ex-CEO of the Campbell Soup Company, routinely handwrote thank-you notes to deserving employees around the world, he understood the power of decency. And when the late poet Maya Angelou said, “I’ve learned in my life that people will forget what you said, they’ll even forget what you did, but they’ll never forget how you made them feel,” she recognized the power of decency.

Employee Engagement at Microsoft

When Satya Nadella took over the job of CEO from legendary Microsoft founder Bill Gates and his successor Steve Ballmer, he had big shoes to fill. Nadella wanted to shift the company’s culture. Specifically, he was determined to disrupt a corporate culture long recognized as a nest of intense infighting and silos competing with other silos. That would start by recognizing what employees did well rather than what they did wrong.

After becoming CEO in 2014, Nadella asked all top executives at Microsoft to commit to empathic collaboration. The gesture signaled that Nadella planned to run the company differently from his well-known predecessors. The first step was to address Microsoft’s practice of infighting. He took a number of steps. The first was to encourage humility. He did this by modeling vulnerability. When he did not know something, Nadella said so. He wasn’t afraid to ask for help. He challenged the company’s 125,000 employees around the world to reject a culture of arrogance (“we know it all”) and embrace a culture of curiosity (“we learn it all”). That change has led all stakeholders—customers, partners, and investors—to engage with the company in new, more collaborative ways.

As a result of reorienting the culture, the tenor of almost every Microsoft interaction began to change. Meetings grew more relaxed and productive. Under the previous CEOs, collaboration at Microsoft often saw employees showing off how much they knew (or pretended to know) and jostling for credit and resources. Every participant spent inordinate amounts of time preparing for meetings by appearing to have all the answers and having solutions that were bulletproof to the criticisms of the CEO. The downside of that approach was that it left little room for uncertainty, searching, or collaboration.

Nadella’s approach favors humility. The meetings he runs are organized around the assumptions that humility and vulnerability are essential not only for inspiring cooperation in the office but also for creating products and services that resonate with real customers. As part of this goal, Nadella updated Microsoft’s mission statement from something transactional:

A PC on every desk and in every home, running Microsoft software.

to something transformational:

To empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more.

Which vision statement is more engaging?

Nadella insists that vulnerability is a strength at Microsoft. He wants the culture to focus on growth and skills the organization has yet to master versus preserving market share using skills it has already mastered. The reward is that corporate cultures focused on growth make it their mission to learn new things, understanding that they won’t succeed at all of them.

Yes, this approach increases risk and the real possibility of failure. Failure is the price an organization occasionally pays for real innovation. Nadella wrote off Microsoft’s $7 billion acquisition of Nokia’s mobile phone business as a total loss, acknowledging that Windows lost the battle to be a player in the operating system for mobile phones. It’s not clear that Ballmer, who made the decision to acquire Nokia, would have been so likely to accept such a high-profile failure.

Purpose Statements Build Authenticity

Enterprises are turning to “purpose” and “authenticity” as a way to engage employees and customers alike. It is critical that enterprises brand themselves with a clearly articulated vision and authentic social purpose. This is where a succinct purpose statement comes in. We believe every company can profit by formulating such a vision or purpose statement. The statement can be grand and aspirational. Most importantly, the company, by its daily actions, should be seen by stakeholders as living up to the statement.

Consider a few of our favorite purpose statements:

Starbucks: To inspire and nurture the human spirit—one person, one cup of coffee at a time.

3M: To advance every life and improve every business while using science to solve the world’s greatest challenges.

Pepsi-Cola: To improve all aspects of the world in which we operate—environmental, social, economic—creating a better tomorrow than today.

Adidas: To be the global leader in the sporting goods industry with brands built on a passion for sports and a sporting lifestyle.

Nike: To bring inspiration and innovation to every athlete in the world.

Let’s compare the Nike and Adidas purpose statements. We appreciate the Nike vision statement because, while it seems unnecessarily restrictive (“every athlete”), it soon becomes clear that Nike believes that by virtue of having a body every human being in the world is an athlete. Which statement resonates more? Which one better speaks to you, regardless of whether you are a customer, partner, or investor? We give the edge to Nike. Besides being wordier, Adidas puts the emphasis on a sporting lifestyle. That’s fair. But using half as many words, the Nike statement addresses not only people’s interests but their sense of who they are.

The vision statement needs to be cocreated by consultation with all stakeholders. Employees are not just workers. Employees are cocreators. They want the purpose to be their own. Purpose needs to be shared.

PricewaterhouseCooper’s Bottom-Up Mission Statement

The accounting and auditing firm PricewaterhouseCooper (doing business as PwC) recently completed a bottom-up, multiyear project to define its mission statement and values. By bottom-up, we mean the project saw more than 200,000 PwC employees in dozens of countries participating in the program. Unlike most corporate branding initiatives, which are conceived at the top, PwC let employees generate the content and wording of their mission statement. Here is the powerful product of this approach:

Our purpose is to build trust in society and solve important problems.

Note that for the company’s purpose, the employees emphasized not the actual services the company offers—accounting and auditing—but something far more encompassing: trust in the service of solving important problems. We are impressed by the results of this exercise and commend the bottom-up approach to other organizations. PwC’s mission statement goes on to say:

Our purpose is why we exist. Our values define how we behave. In an increasingly complex world, we help intricate systems function, adapt and evolve so they can benefit communities and society—whether they are capital markets, tax systems or the economic systems within which business and society exist. We help our clients to make informed decisions and operate effectively within them.

After this general statement, the PwC code identifies the set of values and behaviors that PwC stakeholders are required to honor if they wish to remain associated with the global PwC community. The guide holds everyone, including leaders, to account for doing their best.

Specifically, when “working with our clients and our colleagues to build trust in society and solve important problems, we . . .

• Speak up for what is right, especially when it feels difficult

• Expect and deliver the highest quality outcomes

• Make decisions and act as if our personal reputations were at stake

• Stay informed and ask questions about the future of the world we live in

• Create impact with our colleagues, our clients and society through our actions

• Respond with agility to the ever-changing environment in which we operate

• Make the effort to understand every individual and what matters to them

• Recognize the value that each person contributes

• Support others to grow and work in the ways that bring out their best

• Collaborate and share relationships, ideas and knowledge beyond boundaries

• Seek and integrate a diverse range of perspectives, people and ideas

• Give and ask for feedback to improve ourselves and others

• Dare to challenge the status quo and try new things

• Innovate, test and learn from failure

• Have an open mind to the possibilities in every idea

Your Purpose Statement

We encourage every company to articulate a shared purpose statement. The task is difficult, especially if you do it the right way by involving thousands of stakeholders at every level of the organization and building the statement from the bottom up. Logistics aside, the task starts by every stakeholder engaging with questions that start with the words “What is the shared purpose?”

• What is the shared purpose that we and our customers can work on together?

• What is the shared purpose that is a natural expression of who we are and what we stand for?

• What is the shared purpose that connects how we make money and how we contribute to the world?

Decencies are baked into the shared purpose statement by creating an organizational culture that ensures that the firm’s purpose and values are always the screen through which decisions big and small are made. When things are going well and profits are good, there is usually little risk to the congruence between purpose and behavior. But every enterprise faces tough economic times. These are the moments of truth when the purpose statement is tested and the company answers for itself the question of how much it actually values its culture and principles.

A good test of whether a company is acting in congruence with its purpose statement is to consider whether a proposed course of action is at the core of the decision. All the examples of corporate malfeasance that we have considered in this book readily fail this test. It will be remembered that Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf, for example, lost his job when it was revealed that bank employees routinely opened new accounts and issued insurance policies and credit cards for customers who had not requested them. In doing so, the company demonstrated that their purpose was not at center stage of their actions. When purpose is at the center of the action, the results are a lot different. Whole Foods, for example, won applause by selling only seafood that was certified as sustainable. Even though the higher prices of certified seafood translated into decreased sales, Whole Foods maintained the principle.

If the “little things” (small but meaningful gestures) take hold and become pervasive, they create stories and patterns and textures that can enrich a culture. These little things have power because they can be felt every day by everyone. They become a unifying experience that becomes sustainable by the force of everyone repeating them.

An “ethical culture” should be seen as part of the tangible, homegrown, specific behaviors and time-honored traditions that form the fabric of an organization, help ensure its sustainability, and help reduce its vulnerability. It’s as if to say, “That’s how we do things around here.”