CHAPTER 6

ADD COLOR

How Do You Yell at a Three-Year-Old?

Your three-year-old son is chasing a ball into the street. You have to yell at him to stop. How will you say it? Try this first. In your normal conversational voice, say, “Stop.”

Seriously. Unless you’re in a car that someone else is driving, say it out loud. You need to feel how it sounds. Say it one more time.

Listen to your voice. Hear your natural volume and tone.

Now imagine that your child is in danger of being struck by a car if you don’t get him to stop right now. Unless you are on a plane, say, “Stop!” like his life depends on it. Can you feel the difference?

What changed?

Something changed physically in how you spoke. If you can recall the difference between your natural voice and the extreme ends of your range, you can use it in other settings.

This is the technical part of how you communicate at work. Aristotle understood that no matter what you are saying, how you say it makes the difference between success and failure:

Still, the whole business of rhetoric being concerned with appearances, we must pay attention to the subject of delivery, unworthy though it is, because we cannot do without it. The right thing in speaking really is that we should be satisfied not to annoy our hearers, without trying to delight them: we ought in fairness to fight our case with no help beyond the bare facts: nothing, therefore, should matter except the proof of those facts. Still, as has been already said, other things affect the result considerably, owing to the defects of our hearers. (On Rhetoric, Book III, Chapter 1, 1404a.)

Aristotle found delivery unworthy because he wanted the content to determine whether what you said won an argument. He also knew that this isn’t reality.

We are easily swayed by a speaker’s charisma. We are too often more impressed with the swagger of a speaker than with the substance of the message. That makes your delivery all the more important if you want to be an effective leader. The most powerful message in the world, backed up by data that proves your idea, will produce the best results. But it can still fall flat. If your delivery is poor, you will fail.

The Sixth Technique: Add Color

The science of speech communication has two physical dimensions: voice and speech. Voice is the sound that you are able to produce when air travels through your vocal cords. Speech is what you do with your voice. There is not a lot you can do to change your voice. It takes an immense amount of specific exercise, like targeting muscles at the gym. Few busy people have time to put in the work. Adding color is about controlling your speech. With the voice you have, you can have so much more impact when you intentionally craft the way you speak.

The Recipe

The final technique for mastering communication at work, the one that, like the brightest spot on a painting attracts the viewer’s eye, is to:

1. Identify the intent of your message.

2. Employ the four horsemen (see the next section).

3. Match your tone to your meaning.

4. Learn how to navigate silence.

5. Record yourself to learn exactly how you sound.

The Method

Adding color is about making the words you choose stand out and express what you mean more clearly. It’s like being on the radio. People can’t see you. You have to emphasize words—vary your tone, cadence, and inflection—to express your meaning clearly. Even when people can see you, adding color matters. You have to choose how you’re going to emphasize a word or point by selecting one of four categories. As you become a master communicator, this will become second nature. You can become so conscious of how your body responds and how your voice sounds that you no longer have to think about making changes.

The best leaders had to learn this too. You have to use trial and error to find what works for your voice, your body, and your message. The easiest ways to add color are to:

Change the speed. Speak faster or slower to create energy and allow your listeners to follow along.

Change the volume. Speak louder or softer to gain their attention.

Change the stress. Lengthen or shorten a word to emphasize its meaning.

Change the inflection. Raise or lower your pitch to ask a question or assert authority.

These are the four horsemen of delivery. When you pay attention to every one of them, like a jazz musician improvises, you can adapt your speech to engage your listeners. You want them to understand what you’re saying without having to work too hard. A listener who has to strain to pay attention to the way you speak doesn’t have the cognitive energy to appreciate your message and its meaning.

Even if you get comfortable with the four horsemen, tone matters too. If your tone doesn’t match what you’re trying to say, people will be confused. If your tone is frustrated and you’re trying to tell someone that you believe in her, she simply won’t accept it. You may want to be happy for someone, but if your tone doesn’t have joy in it, she will think you don’t mean it. People won’t trust you if your message and your tone aren’t consistent.

One more effective way to add color, which grabs people’s attention, is to stop talking. Even more powerful, if you are comfortable waiting, is holding the silence like a soufflé that will fall if you’re not careful. Holding silence commands the respect of the people in the room. Your ability to pause guarantees that they listen to what you say next. If you lose your train of thought, that’s okay. The pause actually helps the listeners prepare for what you’re about to say. If you can master silence, you can own the room.

Your ability to add color and highlight it with silence can’t improve without help. Again, a trusted colleague, a communication advisor, or the rare spouse who can deliver effective feedback—ideally without reminding you that your real problem is that you left your underwear on the floor (send your spouse Chapter 10 for the proper format for criticizing you)—can make sure that your delivery emphasizes the meaning you intend. Candidates for political office practice for days, sometimes weeks, before debates. Professional speakers do exercises every day to train their voice and master speech. The more time you practice with someone who can give you direct feedback, the more quickly you will know when your speech is most compelling.

QUICK TEST

Are people engaged when you speak? This is not about popularity. If you can add color, you create interest and energy.

The Four Horsemen

Speed

Speed is broken into two parts: rate and pace. Rate is the speed at which your words are put together. Pace is the speed at which your thoughts are put together. You can change the speed of your words to create a dramatic effect, the way a conductor slows or hurries an orchestra. To practice, say, “I am the greatest communicator in the world” as fast as you can. Now say it slowly. Now even more slowly. Now even slower than that. This is not to make you sound ridiculous, although you will. It’s to show you the range that you possess right now. You can vary the exact same sentence in intense ways that add incredible energy to what you’re saying.

Regarding pace, when you come to a really important point, slow down. You may want to build up a bit of speed before slowly saying the main information that you want people to remember. There is no one right way to change speed. What will become natural for you depends on what your listeners need. If you are speaking to an older crowd, the trend is to go more slowly. Younger listeners usually need more pace. The secret is variation, and the result is that people hang on your words.

Volume

Volume, whether loud or soft, can raise or shrink your ethos. When you can speak in a louder volume, everyone notices. In a big room, this allows you to reach more people. If you’re one-on-one or in a meeting, the strategic use of louder volume suggests confidence: you’re not afraid to draw attention to what you’re saying. If you increase your volume unintentionally, you appear unaware of yourself. If you maintain a loud volume all the time, you become known as the loudmouth.

A whisper can also raise your ethos as a speaker: What you’re saying is so special that it’s a secret. In a large crowd, you make people feel as if they are among the chosen few who are receiving the inside knowledge. In a group setting, a whisper forces folks to focus in and listen. If this technique is used intentionally and occasionally, your point can be louder with a whisper. If you whisper the whole time, however, you’ll be the quiet one on the team.

The best use of volume is within a range. If you are outside this range, people either back away or lean in and ask you to repeat yourself. To know if your volume is normal, the next time you’re in a group meeting, place a recorder in the middle of the table and listen to the volume level of the other people in the room compared to your volume when you’re talking. Is it easier or more difficult to understand their voices in comparison to yours?

There are two ways to create volume: you can either bang your vocal cords together harder (that’s yelling—do it all day and you get a sore throat) or project from your belly. To get louder and not hurt yourself, push out your stomach as you take in a deep breath. This lowers your diaphragm and fills your lungs with more air.

Stress

Changing the stress on a word either stretches the word out or shortens it. It calls attention to a particular word and emphasizes that word’s meaning. It shows a sense of confidence that you chose that word on purpose. For instance, if you say that this is a “long” table in a normal voice, your listeners know that you think it’s a table of good size. But if you say this is a “looooooong” table, the emphasis tells them that this is the longest table you have ever seen. You didn’t have to say “really, really long,” or “This is the longest table ever built.” Lengthening a word emphasizes the size or importance of what you’re saying.

Inflection

Your inflection is your pitch. It is the raising or lowering of your pitch that either creates a question or asserts your authority. When you ask a question of someone, your pitch goes up at the end of the sentence. In a Western culture, if this happens unintentionally, it’s called “uptalk.” If your voice goes up at the end of every statement, it sounds as if you are continually asking questions. You come across as tentative. In Asian cultures, uptalk can be a part of the standard pattern of speech, so it is not seen as negative.

If you lower your pitch, you sound powerful. Lower your pitch too far, however, and it can become a distraction. Say the word “yes” in a normal voice. Now say it as a question: “yes?” You’ve just raised your pitch. Now say it like a giant. When you deepen your pitch, you express a confidence. The key is to be aware of the inflection you are using and why.

Your Tone Is Your Meaning

We start learning about tone at birth. The way a new mother talks to her baby helps us feel comfort. Around the age of two, we learn a different tone, and it doesn’t feel good. For example, it’s the tone our parents use to yell at us when we are about to touch the hot stove. They say, “Don’t touch that.” But it’s not the words we remember. These experiences of tone stay with us. If you use the wrong tone with your people, you bring up their most primal memories. Their memories interfere with your message.

The best way to learn tone is to practice with someone and record the session. The other person will be able to tell you if you sound like you want to. When you play back your words, you will hear the way you come across. The exercise is simple. Say, “I like cheeseburgers” in different tones. You need to know what you sound like when you are angry, happy, sad, confident, or worried. The secret with tone is that the meaning is independent of the words. When you know how to add the right tone to match what you’re saying, your message becomes clear.

A common example of this is “I’m gonna kill you.” If it’s someone saying this to his brother, he may just be angry. If someone is saying this to her best friend who did something nice, the tone suggests that she shouldn’t have. If it’s a dangerous criminal saying it, the tone probably means real trouble. Tone portrays meaning and needs as much attention as the words you choose.

How to Win an Election: George Bush and Barack Obama

George Bush was repeatedly captured bumbling his words and saying the wrong thing during his runs for president and time in office. But he still was more compelling than John Kerry on the campaign trail. John Kerry’s speeches were like a white wall, where nothing was clear because everything sounded the same. While Kerry was able to break his speech pattern and sound more conversational when he talked about his family, George Bush won the election because he used a tone that more people could connect with when talking politics.

Barack Obama was not a proven leader when he was elected in 2008, but he was a proven speaker. John McCain had the experience. He was a war hero. But on the campaign trail, no matter how good his ideas were, he often sounded angry. Hundreds of people came out to see John McCain. Tens of thousands came to hear Barack Obama. There was no crowd that he could not rally, and no speech that he could not infuse with a charisma that people remembered. His tone further emphasized his message. People didn’t have to work to get the feeling of his vision. They may not have even remembered what he said, but they wanted to follow.

This lesson is not only political. It’s about the power of communication. If you cannot strategically change your tone so that it matches your intended message, the person who can will beat you even if your ideas are better. She will close the deal, she will get the promotion, and she will be the leader that people want to follow.

They Will Sit on the Edge of Their Seats

Just listen. Wherever you are, listen. What do you notice? The simple act of intentionally listening heightens your sensitivity to sound. When you pause in any communication, you are doing the same thing. Pauses are comforting in a presentation because they allow your listeners a brief moment to catch up. If your pauses are too predictable, however, your speech will develop a repetitious pattern. That will lull your listeners into a trance or lead them to imagine going to the beach.

With a big crowd, before you start, pause. In between stories, pause. Before a transition, pause. Before you are about to tell your audience the most important thing they have ever heard another human being utter, pause for a long time and look beyond the crowd. You have just colored your next words with gold.

Say, “Silence reveals the message.”

• Now count to one in your head in between each word.

• Now count to two after saying “Silence,” then finish the sentence.

• Now count to three after saying “Silence reveals” before saying “the message.”

What did it feel like to pause? It may be uncomfortable at first. When you can trust yourself enough to intentionally be quiet in conversations, meetings, or presentations, you can command attention.

The Pros

Professional speakers, whether on the lecture circuit or in the media, add notes to their presentations to remind them where to add color. You might never see this because the speakers have completely mastered their talk. But they went through an intentional process to master the four horsemen, tone, and pausing.

They begin by underlining the words where they want to add impact. Many of them usually work in pencil because as they practice, they figure out what’s really at the core of their message. Then they test whether to add volume or stress, speed or inflection. In addition to underlining, they use arrows up and down for volume or inflection. They will add a slash at any place they want to pause, adding extra slashes for additional seconds.

With a marked-up script, they record themselves. Even the pros record themselves or work with communication coaches. Even if you have become one of the best speakers in the world, no two talks are exactly the same. Every group of listeners needs a different emphasis to understand what you’re really trying to make clear. For those who present without a script, the effort is the same, but they write down color words as a list. The list reminds them not only of their message, but of the intentional moments where they need to employ the four horsemen.

Rarely in your working life will you have to use a teleprompter. Most executives run into them only at big conferences, during a video recording for investors, or when doing a webinar. Teleprompters introduce another person into your presentation, controlling the speed at which the text will flow across the screen. It is essential that you practice with that person ahead of time or describe the way you like to talk. Pros always check in with the teleprompter operator because that quick relationship can determine how effective you’ll be in a high-pressure situation. Free software that simulates using a teleprompter is available for any computer if you need to practice.

How to Sound Like a Leader

Cultural Color

An American speaks in a loud, direct voice. If the volume is louder than normal, an American audience knows that the speaker is extremely serious about what he is saying. But for many Indian men, this is how they talk when they are comfortable. Now suppose an Indian man is speaking with a Malaysian woman. He thinks he’s being friendly when he speaks in a loud, direct voice. She thinks he’s being rude. The color you use depends on whom you are talking to and where you are. Take the time to learn the cultural norms of speakers for the location where you plan to present.

How Cold Is Your Water?

You may not have time to exercise your voice, but you can make sure that you don’t damage it. You already know that you shouldn’t drink caffeine, alcohol, or dairy products before a talk because they change your voice. What is the biggest secret to sounding great? Room-temperature water. Your vocal cords are muscles. Chill the muscle and you lose the flexibility. You will lose the dynamic quality of the voice that you already have if your vocal cords are cold. Room-temperature water keeps your voice lubricated, and the words will sound better.

Plosive Sounds and Assimilation

Assimilation is the blending of sounds, blurring the listener’s understanding of what you are saying. When you say “Gimme” instead of “Give me” or “Ya wanna” instead of “You want to,” you can sound sloppy. Assimilating words is not a big deal by itself. If you say, “Gimme a cup of water,” around people who know your speech pattern, you’ll probably get a cup of water. But once you’re around people who don’t know the way you speak, if you assimilate, you could be misunderstood or seen as too casual.

The reason has to do with our brain’s amazing ability to process information. The average person talks at about 183 words per minute. You can think at about 600 words per minute. That means that the average person has around 400 words a minute bouncing around in his head while you’re talking. He can spend that bandwidth either processing your message and reacting to it or struggling to pay attention. Assimilating forces your listener to work harder. That’s why listening to someone with an unfamiliar accent exhausts you.

Everyone assimilates. Even sign language has versions of assimilation. Master communicators can turn it off in a second by emphasizing plosive sounds. In the English language there are dozens of phonemes, the units that make up the plosives. The exact number varies between dialects and countries. This is not a lesson in speech therapy, but be aware that eight specific sounds make up the plosives. If you don’t emphasize these sounds, your words get lost. You need to know these sounds so people hear your most important messages if you want to come across as a leader.

The sounds are called plosives because they explode out of your mouth. When you assimilate, you implode the sounds. Instead of saying, “Don’t,” you drop the t off. Other people hear “Don.” Most listeners are polite enough to fill in the t for you. But you’re making your listeners do the work. That doesn’t mean that you should walk around hitting every single plosive all the time.

There are three situations where you definitely want to hit them. The first is any time you’re on the telephone, where your listeners do not have nonverbal communication to help them. Second, you use them any time you use technical terms. A technical term is any term that your listener doesn’t know. Even your name is a technical term if your listener doesn’t know it. Third, you use them any time you want to sound authoritative. If you turn on the plosive sounds, you will see an immediate reaction.

When you start hitting strategic plosives, you’ll notice a difference in your listeners’ response. Try delivering the frame for a meeting, the one-sentence summary of what you need your team to get done right away. Simply telling someone he did a “GreaT JoB!” emphasizes the validation. Plosives break you out of your speech pattern and reveal your confidence in your message. When you start using them more often, no one will approach you and say, “Hey, nice plosives!” People will simply feel that you mean what you’re saying, and that you’re not afraid to emphasize that it’s important. Assimilation isn’t wrong. The skill is to be able to turn it on or off.

PRACTICE THE TECHNIQUE

Drill 1: Playing with Tone

With your team, practice tone like your next deal depends on it.

1. Pick a sentence that relates to your company—a mantra or tagline. For example, if you worked for Nike, “Just Do It.”

2. Have someone pick a tone, such as angry, happy, or mean.

3. Have the group pick someone to say the phrase in that tone.

4. Have the person do it until the group finds the tone believable.

5. Have that same person pick another tone and pick the next person.

6. Repeat until everyone has had a turn.

This kind of improvisational drill with your team may feel artificial at first. Some people may find it to be uncomfortable. But the payoff will be worth it when they can control their tone in front of clients and other listeners.

Drill 2: Counting to Three

Before making the most important point of your presentation, count to three. Watch the eyes in the room as they suddenly all look at you expectantly.

1. Know the point you want everyone to remember.

2. Be silent for three seconds right before you deliver that point.

Be sure it is your most important point, because your listeners will remember what you say next.

Drill 3: Overexploding

If you practice the plosives enough, they will become natural.

1. Say, “Plosives are neat but hard to repeat” five times.

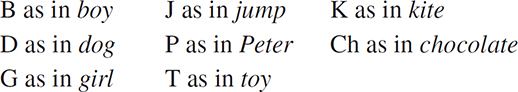

2. Emphasize the plosives—words with B, D, G, J, P, T, K, and CH.

3. Record yourself.

4. Circle the sounds you dropped.

5. Emphasize them and say it faster.

The more quickly you can say the sentence, emphasizing every plosive, the more natural the sounds will feel to your listener, and the more he will be engaged in your communication.

THE TEST

How hard do people have to work to understand what you’re saying? When you add color, the room changes. Faces light up. People’s body language is more engaged. They are more interested in what you have to say because they don’t have to struggle to understand you. The more people have to process what you mean, the less time they have to consider whether they agree with your message. The less you make them work, the more they can focus on solving problems and figuring out the next great thing.