INTRODUCTION

Arm me with audacity.

—William Shakespeare

English Renaissance poet, playwright, and actor

Nothing truly valuable arises from ambition or from a mere sense of duty.

—Dr. Albert Einstein

German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of relativity

The Root Cause is about change because nothing is more constant than change. Change is about decisions and events that disrupt a business system’s integrity, but it is also about implementing solutions to restore system integrity and making course corrections in order to pursue a new strategic direction. Hence, change is the opposite of routine—business as usual.

Routine operations are the hallmark of a system. Therefore, maintaining, renovating, and innovating those processes is key to operational effectiveness and efficiency. Yet, over time, these initiatives tend to increase system complexity—making processes more interdependent and increasingly reliant on key resources they share for the fulfilment of their individual functions.

Complexity, in combination with unfolding new and unforeseen circumstances, produce systemic problems that manifest themselves throughout the enterprise. Fixing these problems is a unique executive responsibility because every lower ranking hierarchical leader will experience a conflict of interest with their peers when they try to solve the issues on their own. The main source of conflict lies in people’s fear that the burden of change will not be shared equally among all departments involved—a state of affairs that higher level leaders must acknowledge and address.

Systemic problems tend to be stubborn because their root cause(s) are not obvious; it takes a deliberate and concerted effort to diagnose them and to create authentic solutions. Unfortunately, only a few CEOs deliberately choose to initiate and sustain such an effort. The majority of CEOs tend to favor investing in the same familiar solutions that caused the systemic problems in the first place—because they find them prudent, safer, and easily defensible because others have already opted for the same solution. This is precisely why systemic problems are so costly and why they can linger in the system for such a long period of time. Nothing changes until someone intervenes with innovative and effective solutions, or until these problems unleash a destructive chain reaction—whichever comes first.

WHO SHOULD READ THE ROOT CAUSE AND WHY?

It is often said than anyone can become a leader—whether they are born or made. But not every leader can change the business system. Only those who are authorized to approve such initiatives can. Therefore, people without authority to make changes to the system cannot be held responsible when the system produces unintended and unwanted results. Without authority, there can be no responsibility!

The Root Cause is intended for current and future chief executives. After all, the CEO position confers the right to exercise ultimate authority and thus the duty to assume ultimate responsibility for the business’s success and failure. Because systemic problems are difficult to solve without a CEO’s active involvement, these kinds of problems are not just business problems, they are a CEO’s personal problems. Failing to solve systemic problems adequately and in a timely fashion negatively affects a CEO’s performance review, and can possibly lead to his or her dismissal. Indeed, studies show that board members have grown increasingly intolerant of underperforming chief executives.2

Instead of promoting a new tool, more advanced technology, or a best practice, The Root Cause advocates that leaders adopt a new level of thinking. The rationale behind this approach is found in the universal law of cause and effect, in which thought represents the level of cause, and real-life experiences represent the level of effect. If all you get are unintended and unwanted outcomes, you’ll have to change your level of thinking. There is no other way.

The Root Cause is also intended for other C-suite executives, consultants, coaches, advisors, counselors, and board members who assist CEOs in their decision-making processes. In order for them to be effective, they will have to rise to the chief executive’s new level of thinking. Their thinking must be aligned, because opposing thoughts combined with a conviction of their validity will inevitably lead to unnecessary friction and conflict with little chance of reconciliation or compromise.

The Root Cause is also intended for educators of the aforementioned categories of people, because they are instrumental in shaping their students’ minds and thus their perception of good business practices and how they should go about creating authentic solutions for stubborn systemic problems.

Last but not least, The Root Cause is also intended for venture capitalists and angel investors. After all, their understanding of the importance of motivating executives responsible for the businesses in which they invest to rethink their approach to solving stubborn enterprise-wide problems, improves these financiers’ influence on increasing the return on their investment.

Willingness to Make a Difference

In addition to possessing the necessary enterprise-wide authority, organizational change requires a personal sense of purpose, as well as a vision for developing the best possible system. If you’re a CEO, this implies that you’ll have to decide what you want your legacy to be. You’ll have to make a conscious decision on who you want to be, the values you espouse, behaviors you’ll display, and how you will inspire others as their chief executive.

To my knowledge, nobody explained this critical decision better than the late Colonel John R. Boyd, USAF, who was known for his “To Be or to Do” speech:

Tiger, one day you will come to a fork in the road, and you’re going to have to make a decision about which direction you want to go. If you go that way you can Be somebody. You will have to make compromises and you will have to turn your back on your friends. But you will be a member of the club, and you will get promoted and you will get good assignments.

Or you can go that way and you can Do something—something for your country and for your organization and for yourself. If you decide you want to Do something, you may not get promoted and you may not get the good assignments and you certainly will not be a favorite of your superiors. But you won’t have to compromise yourself. You will be true to your friends and to yourself. And your work might make a difference. To Be somebody or to Do something. In life there is often a roll call. That’s when you will need to make a decision. To Be or to Do. Which way will You go?3

The Root Cause is intended for anyone in a position of authority, intellectually curious about systemic problems, and inspired to make a laudable difference in creating authentic solutions for their organization, their country, the planet, their fellow man, and ultimately for themselves. And, in the end, by choosing to Do something you will create a legacy worth remembering.

THE QUESTIONS THAT MUST BE ANSWERED

Dr. W. Edwards Deming, America’s eminent scholar on quality management, said: “There is an excuse for ignorance, but there is no way to avoid the consequences.” To avoid the consequences of ignorance, it’s important to answer the following questions:

• Why do executives feel threatened by complexity?

• Why is promotion in rank causing occupational incompetence (the Peter Principle)? (See Chapter 1.)

• What does it take to improve business performance sustainably?

• Which prerequisites and critical success factors need to be satisfied first in order to raise bottom-line results consistently and sustainably, while being respectful of humanity?

• Why do unfolding new and unforeseen circumstances erode CEO effectiveness?

• How can we experience gigantic problems when everyone is just doing their job?

• Why are authentic solutions for systemic problems so hard to pursue, get adopted, and be implemented?

I think the answers to these questions, and many more, should be found in this well-known quotation attributed to Dr. Albert Einstein: “The problems that exist in the world today cannot be solved by the level of thinking that created them.”

In other words, our current level of thinking is ill-equipped to successfully explain a business system’s actual state in terms of its many cause-and-effect relationships. Consequently, we need to embrace a new or up-to-date level of thinking because, as Eckhart Tolle explained in his book The Power of Now, “Once you understand the root of the dysfunction, you do not need to explore its countless manifestations.”4

RECURRING AND PERSISTING PROBLEMS

The root of the dysfunction manifests itself as a chain of effects, such as disappointing top-line results, poor bottom-line results, low employee engagement, the war for talent, a lack of creativity and innovation for self-renewal and reinvention, insufficient differentiation and sustainability, eroding profit margins and an ensuing attrition price war with competitors, a disregard for generating long-term value, loss of integrity (which reduces credibility), erosion of leaders’ trustworthiness, inadequate social responsibility, absence of environmental consciousness, disrespect for humanity, ethics violations, fraud, executive burnout, and a high CEO turnover rate.

Executives who describe their work experience as “putting out fires” and “up to their elbows in alligators” are, in fact, expressing frustration with these stubborn symptoms of a failing system. Whenever they think they solved one symptom, another one pops up somewhere else, or the same one is so persistent that it keeps coming back. It feels similar to playing the arcade game Whac-A-Mole.

As if being preoccupied with the countless manifestations of unknown root causes is not enough, executive performance is measured by the person’s ability to improve financial performance year over year. Executives are thus faced with two challenges. First, solve the current level of underperformance. Second, work even harder to reach new targets. I would posit that there’s a third challenge that’s even more important: changing one’s current level of thinking about business in order to solve systemic problems.

The truth is that the lead time for showing some initial results from a business system reorganization is close to a chief executive officer’s average tenure. In other words, there is little time left for making adjustments and changes when the reorganization is not 100 percent successful the first time around. In addition, board members’ and shareholders’ tolerance for underperformance has dropped. Consequently, the incentive for being creative and innovative is, to say the least, not overwhelming, and yet there seems to be consensus among business leaders worldwide5 that creativity is the answer to solving system complexity. Now, ask yourself, how can creativity be successfully applied when the situation is not fully understood? Be that as it may, the gauntlet has been thrown down for every current and future CEO.

Are you up for the challenge?

MENTAL PROGRAMMING

Scientists have proven that we can only “see” what our brain is capable of accepting as valid and true—yet our eyes see more than the brain registers. That means our perception of the world depends on our beliefs, assumptions, ideas, concepts, theories, principles, values, or techniques we use to explain our experience. Therefore, we should be able to solve stubborn systemic problems by opening our minds to any previously unknown or rejected beliefs, assumptions, ideas, concepts, theories, principles, values, or techniques. These mental constructs contain the potential for unlocking the appropriate cause-and-effect relationships that—eventually—allow us to solve stubborn systemic problems.

Reality is what it is and as it is. We can only change ourselves—our orientation and with that our perception of reality. Because not everything we perceive is true, perception is just a belief, which is subject to change.

Therefore, although we often cannot change the reality of a situation or condition, we can change our experience, perception, or orientation toward a specific situation or condition. The ability to change one’s orientation is the source of ingenuity, resourcefulness, originality, and authenticity, which is instrumental in finding solutions where we couldn’t possibly see any before. This is also an interesting explanation for the biblical dictum of turning the other cheek6—to change one’s perspective and look at it from a different angle or with a different mindset. And that is how effective executives distinguish themselves from others with the same know-how.

Our mental programming or orientation informs us about phenomena that we believe to be possible, valid, and true. Rather than progressing in a linear and continuous way through education and life experience, our curiosity needs to open up our minds toward the possibility of new approaches to understanding the nature and character of a complex business system. For example, although the common dominant level of thinking informs us that making money is the purpose of a business, you might become compelled to adopt a new level of thinking that believes the purpose of a business is to become the obvious choice supplier to members of an intended target audience.

Please stop and think: From which people or businesses do you think the money you intend to make will originate? And with whom would those decision makers prefer doing business—someone who enters the relationship just for the money or someone who takes pride in solving real human needs? Which relationship promises to be more cost-effective and sustainable in the long run? Is your answer at odds or aligned with the common dominant level of thinking?

Many in the scientific community consider the transformation of how we now regard consciousness—and its dramatic consequences for our understanding of reality—a paradigm shift in their thinking. The challenge posed by these paradigm shifts in the way we think is that they do not allow for a cafeteria menu from which to pick and choose according to one’s mood or liking; there is no middle ground. Is that why we are so resistant to change?

DESCRIBING VERSUS PRESCRIBING

Most forms of instruction and advice on business practices, and on leadership specifically, prescribe how specific symptoms or effects should be addressed. In simplest terms, if this is your pain, then here is your medicine. Consequently, there is an endless supply of out-of-the-box solutions, off-the-shelf technology, universal tools, expert opinions, and best practices that claim instant success. If one solution does not work, you just try harder or try something else.

This rather simplistic trial-and-error perspective on solving symptoms stands in stark contrast with the medical field that admonishes its practitioners with the expression “Prescription without diagnosis is malpractice.”

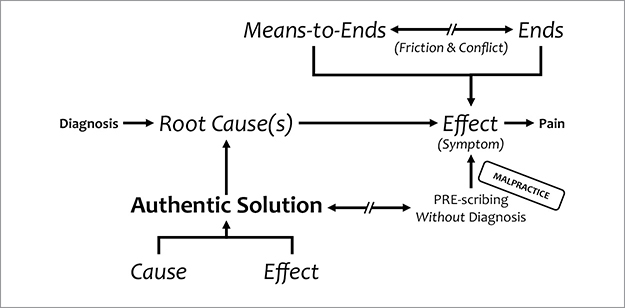

Figure I.1: Need for Diagnosis of Root Cause(s)

Misalignment between means-to-ends and ends causes friction and conflict, which become painfully manifest in various specific effects or symptoms of a systemic problem. Effects can only be treated successfully after diagnosis of its root cause(s). Treatment of symptoms—without knowing their root cause(s)—is malpractice. Root causes can only be solved with solutions which efficacy is grounded in proven cause-and-effect relationships, thus predicting to restore integrity to the system. That is what distinguishes them as authentic solutions.

The purpose of this book is to help executive decision makers diagnose systemic problems by describing cause-and-effect relationships between their decisions regarding the design, organization or structure, implementation or operation, maintenance, and management of a business system and its performance. After all, without recognizing the many symptoms or effects as manifestations of one and the same systemic problem, and without awareness of its root cause(s) that are undermining a system’s capability and capacity, there is no guarantee for creating authentic solutions for systemic problems. That is why systemic problems persist and recur, which undermine business performance.

Consequently, executives who fail to recognize the cause-and-effect relationship between their decisions and the occurrence of systemic problems will also fail to recognize the cause-and-effect relationship between a root cause and its authentic solution. The challenge to a decision maker is not in finding a solution—and in assessing its efficacy, elegance, simplicity, complexity, or the eloquence with which it is proposed—but identifying the right principle, method, theory, or premise that sustains and facilitates the cause-and-effect relationship.

Decision makers tend to settle conclusively on either principles or methods, and/or on specific outcomes. Applying the same method as before is very likely to produce the same outcome as before. In addition, a single method cannot realize two mutually exclusive outcomes—for example, achieving maximum operational efficiency and achieving maximum customer need satisfaction. Each outcome requires its own specific method to instigate the appropriate cause-and-effect relationship.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

In order to explain why trade-off decisions between efficiency measures and effectiveness measures are necessary, this book provides a methodology—business mechanics—for understanding how a business functions as a singular, unique, integrated, and open system. This approach is distinctively different from the methods promoted by mainstream business education institutions, including centers for executive development. Their approach to understanding how a business functions is to study each of the nine constituting links of the value chain separately and in isolation of each other (see Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1), and the purpose of the business system as an organic whole. Their aim is to create material experts for every silo of specialized knowledge within the value chain in order to optimize the efficiency of their silo of specialized knowledge separately and in isolation of every other silo of specialized knowledge.

The conflict between these two approaches is explained by Colonel Boyd, who wrote: “According to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, and the Second Law of Thermodynamics one cannot determine the character or nature of a system within itself. Moreover, attempts to do so lead to confusion and disorder.”7 In other words, the principles or methods that explain cause-and-effect relationships within a separate part of the system cannot explain cause-and-effect relationships within the system as an organic whole. More specifically, the fact that a course of action is successful for the part does not imply that it will be equally beneficial for the system as an integrated whole as well.

Interestingly, executive decision makers from around the world expressed their experience of confusion and disorder because of system complexity in an IBM report called “Capitalizing on Complexity: Insights from the 2010 IBM Global CEO Study.” The obstacle standing between a CEO’s experience of confusion and disorder and solving systemic problems is the individual’s own mental programming—in other words, the principles and methods she or he accepts because of a belief that they are valid and true and those she or he rejects because of a belief that they are invalid and untrue.

Furthermore, there are no better sales techniques, nor are there superior methods for presenting, explaining, demonstrating, or convincing a CEO of the validity of an authentic solution when the deciding CEO rejects the validity of its organizing principle. I can explain it to them, but I cannot understand it for them. Consequently, the curse and the redemption are one and the same; the decision makers’ (un)willingness to change their minds!

Exercising Free Will

Deming said that 94 percent8-9 of all results are systemic in nature, which means they are inherent to the value chain’s design, organization or structure, implementation or operation, maintenance, and management. The CEO must assume ultimate responsibility for the success and failure of the entire value chain because she or he has the right to exercise ultimate authority with his or her decisions to change the value chain. Ultimately, CEOs cannot insulate themselves from the consequences of their actions or inactions.

Executives who use their free will in order to change their mental programming distinguish themselves from others with the same know-how. They are the ones who make a positive difference in the lives of many people and leave behind a great legacy.

Historically, such dramatic changes in one’s personal beliefs have typically been the result of a hero’s journey (as described in Joseph Campbell’s well-known book The Hero with a Thousand Faces), which provides the familiar framework for a wide range of stories about human maturation. The hero goes on an adventure and—in a crucial watershed moment—wins a victory, which transforms forever his or her perception of life and the three-dimensional world in which we live.

The Root Cause is intended to provide such a watershed moment for its readers. Expect to do battle with new and unfamiliar principles that—when you allow them—will transform your level of thinking about business. At times, you may feel confused and irritated when challenged to learn, unlearn, and relearn the simple relationships between cause and effect and means and ends. But you can take solace in knowing that only a new level of thinking can help you create authentic solutions for stubborn systemic problems.

NOTE TO THE READER

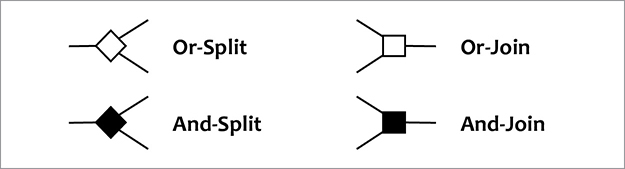

The following legends are used for the illustrations in The Root Cause.