seven

LEADERSHIP

In 2011, as we continued to miss our sales projections, we got a surprising lifeline: a Fortune 500 company offered to buy our software. It would be a multimillion-dollar deal, almost a hundred times bigger than any previous contract. And it was coming at a moment when bankruptcy seemed right around the corner. It couldn’t have been better timing.

Or worse—depending on how you see it.

The prospect wanted us to fully customize our product to suit their very specific needs. We’d go from having a solution that could be used by anyone to one that worked only for a single company. That was counter to our business model. We wanted to build something that could be used by many customers.

On the other hand, Okta had about 30 employees. Their livelihoods were in our hands. If we couldn’t find a way forward, everybody could lose their jobs.

What would you do? Take the deal to save the company, even though it meant giving up on the dream? Or stay true to the original vision and risk losing the company entirely?

Todd and I decided to stay true. It was one of the hardest decisions we’ve ever made. We had no interest in becoming a professional services company—in building bespoke software for individual clients. That business model is actually riskier in the long run. You always have to find new clients. A platform with a subscription model—which was our original idea—was more sustainable, if we could get there. Our board members agreed with us, even though they were as worried as we were about our prognosis. Still, they gave us the green light to turn down the offer.

Luckily, it worked. We ended up selling far more to a vast array of businesses than we ever could have to that one company. But, in that moment, we were tested.

![]()

![]()

Being a leader means constantly being thrown into the fire. You have to continually make decisions with only a fraction of the information you need. When conflicts are percolating inside your company, you have to tackle them quickly, so they don’t get bigger. You have to learn to communicate with a wide range of people and do so in ways that work best for them, not for you.

The fate of your company rests on how you choose to lead. If you played sports in school, you know the difference a great coach makes—and the damage a terrible one can do. A great coach runs the team in ways that enable everyone to succeed. A bad one . . . well, a bad one comes in many forms. Some are scattered and disorganized. Others focus on skills or plays, but not on building confidence or cohesion. Some are loud-mouthed jerks who think more about covering their butts than pulling together. Even a coach who is really nice but unwilling to make tough calls can fail their team.

There are many great books on leadership out there. I personally like the ones that follow the career of a single leader, such as Disney chief Bob Iger’s The Ride of a Lifetime or Bryce Hoffman’s American Icon, which is about Alan Mullaly’s attempts to turn Ford Motors around. (It won’t surprise you I’m also a fan of Ben Horowitz’s The Hard Thing About Hard Things, which is essentially required reading in Silicon Valley.) This chapter, however, contains the kind of rubber-meets-the-road tactical advice that other startup founders have found useful.

First, though, a thought: The irony of being a startup leader is that you have to believe two seemingly contradictory things. You need to have so much ego that you believe that the unlikeliest of events (a startup growing 10×) is within your grasp. But at the same time, you have to subsume that ego every minute of every day. You must give away power and responsibilities so the company can grow. You have to deprioritize your own needs in favor of those of your employees. And most importantly, you need to learn how to listen—to your colleagues, customers, investors, and mentors—so you can collect as much insight as possible to make those great calls. It’s a tricky balance.

Prioritization 101

With a little help from Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Tien Tzuo, my Salesforce colleague and the founder of Zuora, told me a story about a friend of his who moved to a startup after working at a large Fortune 500 company. There, he’d overseen an army of people and spent his days tracking 50 separate “top” priorities. “But now I’m in a startup,” he’d told Tien, “and I know I can’t get all 50 things done.” So he’d narrowed down his list to the 10 most important things. Soon, he discovered that even making progress on just those 10 items was beyond his abilities. He realized he only had the bandwidth to focus on two—just two. “It was the hardest thing to let go of items 3–10,” he said, “because I knew that things were going to fall apart.” Systems would break. Customers would get mad. “But that’s the nature of a startup,” he said. “You have to focus on the things that are going to get you from Point A to Point B.”

Tien’s friend was right. There is so much coming at you in a startup that it’s easy for you to get distracted. And if you get distracted, your people will get distracted. Then it’s just a downward spiral. So you need to “keep the main thing the main thing.” Be ruthless in your prioritization. Here are some principles and practices I use to keep my priorities clear:

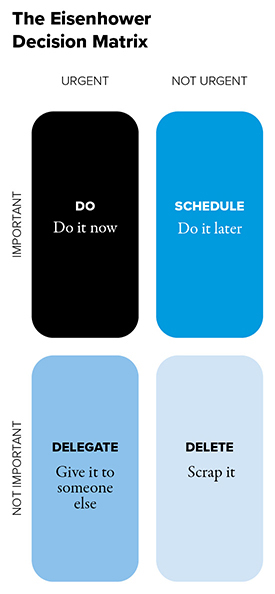

• Use the Eisenhower Decision Matrix. This has different names, but it dates back to Dwight D. Eisenhower, the top US general in Europe during World War II (before becoming the twenty-fourth US president). Eisenhower knew what it meant to make decisions under pressure. His system is very simple:

![]() Stuff that is neither important nor urgent? Scrap it.

Stuff that is neither important nor urgent? Scrap it.

![]() Stuff that’s not important but urgent? Give it to someone else.

Stuff that’s not important but urgent? Give it to someone else.

![]() Stuff that is important but not urgent? Schedule it for later.

Stuff that is important but not urgent? Schedule it for later.

![]() Stuff that is both important and urgent? This is your area of focus. It’s the “main thing.” Make a decision, or at least start working on it.

Stuff that is both important and urgent? This is your area of focus. It’s the “main thing.” Make a decision, or at least start working on it.

• Keep a running to-do list. I use Evernote and Notion, and I keep them synced on all my devices: computer, phone, and tablet. I revise my list several times a day because everything is always changing. Other equally great tools include Box Notes, Dropbox’s Paper, and Google Keep.

• Be stingy with your calendar—very stingy. Question every meeting request. Ask yourself: Does the meeting actually need to take place? If so, do I need to be involved? If so, does it really need to take 60 minutes, or can we tackle everything in 30? Be particularly wary of recurring meetings. You’re probably not needed at most of them. (Every 30 or 45 days, I go through my calendar, and delete all new recurring meetings that other people have added me to. Then I wait to see how many people send me those invitations again, after they notice I’m not attending. Spoiler alert: very few.)

• Control your email; don’t let it control you. Email is what other people want you to do. Ignore most of it. A lot are just FYIs. If you’ve hired great people, you don’t need to follow the play-by-play. Maggie Wilderotter, the former CEO of Frontier Communications, told me that she deletes every email that has more than two people on the “To” line, as well as every one where she’s cc’d. “Then what bubbles up to me are the really critical decisions or ones where I need to move something forward or course correct,” she says. “Otherwise, I trust the people who work for me to get the job done.” Another tactic: I block off two hour-long sessions on my calendar for email: one in the morning and one in the afternoon or evening. Usually, by the time I get around to whatever burning issue has been sitting in my inbox, it’s already been resolved.

• Keep your people focused. Your team will come to you and start talking about five different things. Make them decide what their top two most important things are and then talk about those. When my team starts wandering, I bring them back and ask them: “What’s the main thing?”

Ditch Your 1:1s

Most managers hold regular check-in meetings with their direct reports (often called one-on-one’s or “1:1” for short). But Zuora’s Tien Tzuo says he doesn’t do them. Ever. Let me repeat that: the founder and CEO of a $3 billion company doesn’t have regular 1:1 meetings with his senior executives.

Tien estimates that such meetings can quickly consume 80 percent of his week, which he doesn’t think is the best use of anyone’s time. “I just tell my executives, ‘If you need me, call me. And if I need you, I’ll call you,’” he says. Which makes sense. If you hired great people, why wouldn’t you trust them to do a great job running their groups? Plus, Tien says his approach actually makes Zuora work more effectively. The 1:1 system ends up producing what he calls a “hub-and-spoke” approach to solving problems. “Everything is brought to you instead of your leaders working out issues among themselves,” Tien says.

![]()

Tell Everyone to Keep It Short

The TL;DR approach to executive communications.

One of the most valuable things you can do is to coach your team to keep their communications short and focused. I never read long, meandering emails. I don’t have the time. Instead, I flag them for my next cross-country flight, when I’ll have hours of uninterrupted time—which, needless to say, usually comes weeks later. I’m not trying to be a jerk. But my days are overloaded. Every executive’s are. I only look at email in brief, interstitial moments where I speed through subject headers looking for a clear Ask. When I find one, I act. Otherwise, the messages get buried.

Here’s how I coach my team to communicate effectively:

Emails are modern-day memos. They should follow a standard structure:

• Subject line: Say exactly what you need from the executive. If it’s just an FYI, label it as such (“FYI Only – Upshot of the XYZ meeting”). If this is the fifth in a chain of emails that now says something like “Re: Re: Re: Re: Thursday’s meeting,” rewrite the Subject line, so it will catch the executive’s eye.

• First sentence of the email: Make your Ask so they know exactly what you need from them: “Please approve expenses for X.” “Please comment on budget proposals for Y.”

• List 2–4 bullets spelling out the main takeaways that the executive needs to know.

• Last: Write something to the effect of: “If you need to know more, I’ve included more detail below. And attached are ## documents.”

• After that, write as long as you like.

Presentations

Presentations to higher-ups usually take place because a staffer needs a decision on something, so that should be the focus of the meeting. Keep the main thing the main thing:

• Slide headers should be declarative summaries of the main points. The executive should be able to read nothing but the presenter’s slide headers and understand what they are trying to communicate.

• The presenter should keep the meeting on track. Attendees can go down rabbit holes on nonessential points. The presenter should tell that person they’ll get back to them on that item, and then pull the focus back to the main issue.

Meetings/Phone Calls

My team often asks me to hop into a meeting or onto a phone call for them. Account managers, for example, periodically need me to talk to their customers. Or someone from our Investor Relations team wants me to speak with an institutional shareholder. That person needs to prepare me properly for the meeting, or it’ll be worse than if I never showed up.

At Okta, I have a stack of templates that my team uses to tee me up for different kinds of phone calls or meetings. The forms ask for relevant information, depending on the nature of the contact. For a customer call, the template will ask how Okta was introduced to the customer, how many employees they have, what their annual revenue is, what we need from the meeting, and the key points I need to get across. My team knows they need to fill out this document well in advance, so I can get up to speed. (Each executive at your company should draft their own templates and train their teams to use them.)

I bring these prep documents on customer visits. I even place them directly on the table in front of me, so I can quickly answer any question a customer might ask. Doing so also serves another purpose: Customers often notice the documents and ask what they are. I’ll explain that the notes represent the summary of their company’s needs and our understanding of what they’re looking for. More often than not, the customer will actually ask to look at the documents. If our assessment ends up being off-target, the customer will let us know—which is a good thing, because now we can dive straight into the purpose of our meeting: figuring out what the customer wants and how we can get it to them.

Low-Information Decision-Making 101

Because you’re always flying blind.

One of the hard realities of being a founder is that you consistently have to make important decisions with very little data. People always think that the people at the top have all the information. But they don’t. They might have more information than most people (or, what I like to call “less imperfect” information). But it’s usually only a sliver of what you’d prefer to have. And that’s not just because your fast pace makes it difficult to collect all the necessary information. It’s also because there is a lot of information people won’t serve up to the top dog. (Especially when things are going sideways. No one wants to give the boss bad news.)

But you have to make those decisions. Remember: your money has a fuse on it—you can’t wait. Worse, it never gets easier. Because if you make enough good calls, guess what happens? You stay in business! And the bigger you get, the more complex and high-stakes the decisions become. So how can you get good at making important decisions with imperfect information? Here are a few rules of thumb:

BEWARE OF FALLING FOR PATTERN RECOGNITION

This is often how companies get into trouble. You, the CEO, have just a handful of data points with which to make a decision, and you remember a similar situation from a ways back. You assume that, since the decision you made the last time worked, you’ll make the same decision now. Right? Wrong. Your present context could be very different from the previous one. The company could be significantly larger (or smaller). The resources available now might be different from what you had then. The specific outcome you’re looking to produce might be different. And so on. So, sure, take that last time into account. Use its lessons as one of many inputs. But don’t rely on it alone.

STAY IN TOUCH WITH THE FRONT LINES

Your client reps or salespeople are closest to the customer. They best understand what the customer needs are and how they’ve changed. Use Maggie Wilderotter’s “lion hunts,” a practice detailed later in this chapter. Or develop your own. But make sure you keep a line open.

HIRE OTHER EXECUTIVES WHO ARE ABLE TO MAKE DECISIONS

Here’s a litmus test I use to see if I’m on track with this practice: When I come back from a business trip and walk into my office, if there’s a line of folks at my desk waiting for an answer or decision, I know things are breaking down. Either I’m doing a bad job of pushing information down (and therefore folks don’t have the data they need), or I’ve hired the wrong people, ones who can’t adequately make decisions. Either way, it’s a clear indication that something needs to be fixed—pronto.

TRAIN YOUR TEAM TO WALK YOU THROUGH THE OPTIONS THEY DISCARD

I learned this one from Todd. Often, when one of your reports tells you they’ve decided to go in a particular direction or to work on a specific project, they just tell you about the decision itself. They don’t walk you through the other options they considered and explain why they rejected them. But you need to train them to do just that, because you have more information than they do about the bigger picture. You know what other priorities are coming up, what partnerships or acquisitions are on deck, and what new hires or organizational changes are in the offing. Your more-complete set of information lets you assess all the possible directions more thoroughly and ensure that the one on the table is still the right one.

You Don’t Need to Clone Yourself

But you do need to shed yourself.

I’m a big fan of letting my team members set their own goals. You have a roadmap for the company, right? So let your direct reports decide what their goals will be for the coming quarter. If you’ve hired the right people—smart, ambitious, motivated—they will usually set more aggressive goals than you would. And since they came up with those goals themselves, they’ll usually be more committed to making them happen. Even if they come up short—if they only get 95 percent of the way there—they’ll still be further ahead than if you’d given them their marching orders.

You’ll review the goals, of course. They need to align directly with where the company’s headed. But let them run with it. Get out of the way, except for periodic check-ins. For my team, that takes place every two to four weeks. I let my people lead these meetings and set the agenda. If there’s anything I need to keep on top of (like headcount; we’re always hiring, and I need to make sure my teams are on track), I’ll give them a heads-up so they can prepare. Otherwise, they decide what we discuss.

This is ultimately how you share leadership without cloning yourself. The bigger your company gets, the more and higher-level stuff you, personally, have to take on. That means you need to constantly shed lower-level areas of responsibility. The more ownership I give my people, the more they grow and the more they can take on. In turn, that’s less I have to do, which frees me up to focus on the company’s most important strategic initiatives. Which is the ultimate goal.

![]()

Max Out on Mini Teams

To get big, you might have to start small.

Sebastian Thrun is a fan of autonomy. He cofounded Udacity and, more recently, is building flying cars at Kittyhawk. There, he sets up “mini-companies” organized around the principles of ownership, empowerment, trust, and accountability. “I’m not that smart,” he says. “I can’t make all the decisions.” Each of Sebastian’s mini-companies contains no more than the number of people who could fit in a van or a bus. He gives them a goal and sets milestones. “And then I basically walk away,” he says. “My main job is to inspire people and remove roadblocks. Nothing else.”

In 2019, Melanie Perkins took a similar approach at Canva. With 800 employees, the company had begun to feel unwieldy, so Melanie broke it into 17 groups that she dubbed “mini-startups.” Each was responsible for one of Canva’s target industries, and they were expected to function like actual startups. Each group drafted its own “pitch deck,” outlining the group’s vision and strategy. They received public relations support and managed the onboarding of their own people. “Rather than me having to hold the entire vision and all the details in my head, each group became the owner of their vision,” Melanie explains. “I no longer have to be the person who figures out where every chess piece is and how to move it forward.”

The approach also helps defuse some of the politics that often slow a company down. “Most companies act as if there’s only a fixed amount of pie”—power and opportunities for advancement—“and everyone has to fight for their own little segment,” Melanie says. But “at a startup that’s rapidly growing, everyone’s success comes from expanding that pie.” She expects the number of these groups to grow as Canva does. “Instead of figuring out how to step on each other in order to move up, people focus on how to grow the company as a whole.”

INSIGHT

As the founder, you see so many places where you just want to jump in and be like, “I can fix that. I totally can help. Let me just get involved. There’s a thing I know. Let me just tell you that thing.” You learn over time that that’s the antithesis of building a culture of ownership and empowerment, where people can really own an area of the business. My goal needs to be to contribute in areas where I can uniquely add some perspective. But to do so without disempowering people who are doing great work.

—Aaron Levie, Box

![]()

Always Measure the Stakes

If they’re high, go slow. If they’re low, go fast.

You’ll have so much on your plate that you’ll frequently feel the impulse to make quick, short-term decisions. In many cases, that’s fine, because the stakes are low. Which office should you move into when you have just 10 people? Who cares? You’ll be moving again in a year. Your brand logo? Unless you’re a consumer product where brand identity drives adoption, it likely doesn’t matter a whole lot, especially since you’ll revise it a few times anyway.

But then there are short-term decisions that end up having huge downstream impacts. Hiring and promoting people are two such areas. Here’s a classic example: You’re two years into your company, and it’s time to add a VP of engineering. The person who joined your company 18 months ago as your director of engineering expects to get the job. But in this case, you don’t think the director is up to the task. You need someone who has robust experience as a director in a much larger company, with more complexity and bigger challenges than the director has had at yours. Meanwhile, however, your director has threatened to go elsewhere if they don’t get the promotion, and you don’t want to have that big of a leadership gap in your engineering group. So what do you do?

First, stop and breathe. It’s going to be tempting to give the person the title. They’re here. They’re competent. Why not? Let me tell you why not. Every time you promote someone who’s not qualified, the rest of your team notices. Other folks will expect to get similar promotions even when they too aren’t ready for the new jobs. When you fail to hand out comparable promotions, they’ll begin to question your culture. Are you really about excellence? Or are you actually about some kind of favoritism? Now, you’re in a bind. You might end up promoting those people too, just so they also don’t leave. Before you know it, you’ve got a team of mediocre senior executives.

These kinds of short-term decisions end up rippling outward. Having middling people in leadership slots impacts your ability to hire A players. Great people don’t want to work for B players (much less C players). Once you’ve put a lackluster person in a leadership position, you can basically write off their entire organization.

It also hinders your ability to raise money. Your fundraising packet includes a list of your top executives. A mediocre player on that list is a red flag. Investors bet on teams. They might pass you over now.

So with every decision, take a moment to assess whether it’s a low-stakes decision that you can make quickly or if it’s a high-impact decision with long-range consequences. Specifically, ask yourself: Will this decision send the right or wrong message to my team? What other areas will this decision impact, and are those low- or high-stakes situations? In 18 to 24 months, how much will this decision matter? Then and only then, pull the trigger.

Hit the Clutch Shots

Recognize and focus on do-or-die moments.

As a founder, you’ll be inundated with demands on your time: people who want meetings, decisions that need your sign-off, emails that need answers. You’ll figure out how to navigate all of that. Still, among all those demands, there will be a handful of meetings and presentations—let’s say 20 or so a year—that will really, really matter. Getting them right—or wrong—will have exponentially outsized impacts on your company. For example, a presentation to an enormous customer: nail it and your revenue could soar 50 percent. Or an investor pitch: knock it out of the park, and your startup has another two years of runway. These are life-changing events.

Your job as a founder is to recognize which items on your to-do list are clutch shots—and then optimize everything around them. For example, at Okta, now that we’re a public company, I have to nail our quarterly earnings calls with Wall Street. If I flub even a tiny part of the question-and-answer session, our stock could roller-coaster through billions of dollars. So I optimize everything in the days leading up to those calls. I do tons of preparation, of course. But my assistant also knows to clear out entire chunks of my schedule, so I can get my head in the game. Anyone could bang on her door and insist they need to see me, but barring a life-threatening family emergency, they’re going to have to wait. Even if the cost of making them wait is that we lose tens of thousands of dollars on a deal or we miss out on some great midlevel hire. The cost to Okta of that loss doesn’t remotely compare to the cost if I mess up an earnings call.

When we were just starting out, I would worry over every dollar. Once, when I had to book a last-minute red-eye flight to get to a do-or-die sales meeting, I hesitated to pay the extra $150 for a business-class seat so I could get some sleep on the plane. When I called Todd to get a second opinion, he thought I was nuts. “Of course, you knucklehead,” he told me. “Do whatever it takes to close the deal.” You need to do the same. Money will be tight in those early days. But if flying out the day before and paying for an additional night at a hotel means you’ll be well rested for a key sales pitch, do it. Need to pay extra to get a quiet hotel room? Go for it. Need time to prepare for an investor meeting? Tell your staff to wait until the following week to get your attention—even if it means lower-level mistakes are made in the meantime.

Get Up and Walk Around

The value of visiting the front line.

As Frontier Communications began to grow, Maggie Wilderotter used to take purposeful walks around her offices just to chat with employees. “I would make myself approachable,” she says. “I’d get groups of employees together and answer questions or have a conversation about what’s going on.” Everything was informal. Maggie would ask people what they were working on and how they were doing. She’d inquire about their families and lives outside of work. She’d cheekily ask them what rumors they wanted her to start or, more sincerely, what rumors they were hearing. “You need to make it comfortable for people to interact with you as the CEO,” she says.

The practice was so important that Maggie built it into her weekly schedule. She called these outings “lion hunts” because she—the lioness—would be “prowling around, seeing what’s going on,” she says. “The front line is your company. It’s who the customer interacts with every single day. It was important for me to stay close to and build relationships with people who would tell me the truth about what’s really happening.”

The bonds she built created confidence that people could share bad news without worrying about blowback. “I always built cultures where frontline employees would tell me something before they’d let their bosses know,” she says. That, in turn, would motivate midlevel managers. She’d take those issues to the bosses to find out what was going on. They weren’t happy to be caught short, of course. “But they changed their stripes. They wanted to make sure there weren’t any surprises that would be elevated to me,” Maggie says.

INSIGHT

I don’t think anybody is born a CEO. The skill set itself is a pretty weird, unnatural skill set. It’s important to give people [difficult] feedback. But as humans, we want people to like us. A CEO has to be willing to say things and do things and lead a company in directions that nobody likes. Nobody’s born to do that.

—Ben Horowitz, Loudcloud and Andreessen Horowitz

![]()

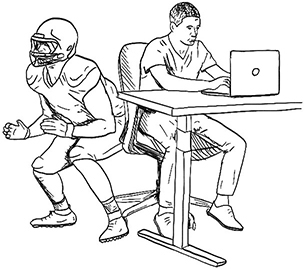

Be the 2008 Steelers, Not the 2006 Eagles

With apologies to Philly fans.

Jeremy Bloom founded his company Integrate, a marketing platform, in 2010. Before that, however, he played in the NFL as a punt and kick returner. (And before that, he was an Olympic freestyle skier.) Jeremy was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles in 2006, and in 2007, he signed with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

The two teams operated in markedly different ways. “The Eagles were a very top-down, micromanaging organization that produced a fear-based culture,” he remembers. “Coaches would consistently tell you that if you didn’t do what you were told, you would be gone, ‘because there are a hundred other guys waiting to replace you.’” This culture of fear meant that each player stayed in his own bubble rather than look for ways to support his teammates. “Guys were always just protecting their own job. It didn’t feel like a lock-arms, one-heartbeat type of culture that you want to have as a football team.”

The Steelers were a completely different story. It was a bottom-up culture where the players were the leaders. “The head coach was a great motivator. He never told you what you had to do, but he always provided ideas on how to achieve your goal,” Jeremy says. “The locker room felt like a family.”

The Steelers went on to win the Super Bowl in 2009 “with what I would describe as a less talented team than what I saw in Philadelphia.” Jeremy took those lessons to heart when he founded Integrate. Here are three ways he baked the “Steeler Way” into his company:

• Empower employees. At Integrate every employee is considered “the CEO of their own job.” “We always hire people who are smarter than us, and we ask them to tell us what they think they should do,” Jeremy says. Employees are given latitude to run their areas, even if that means sometimes falling on their faces. “It’s OK if you make mistakes,” he says, because that’s part of the path to building leaders.

• Help your employees solve problems by asking questions. Even if you know how to do a task that an employee is struggling with, you should start by asking questions. A person will be more committed to a course of action if they come up with it themselves. Plus, they’ll sometimes figure out an approach that’s better than the one the boss would have suggested.

• Hire managers and executives who operate this way. “It’s a major hiring filter,” Jeremy says. “If we get the sense that somebody might be too overbearing or a micromanager, we hire the other person.”

Let Your Employees See You Make Mistakes

“I’ve done a bunch of embar- rassing things,” says Josh James, the Omniture and Domo founder. “For example, we printed up 1,000 books of ‘Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Online Marketing,’ and we sent them out to 1,000 prospects.” The books were all empty. The pages were all blank. Intentionally. The idea, says Josh, “was you’d open it up and be like, ‘What the heck?’ and then you’d call us, and we’d send the real one to you.” It didn’t work out as Josh had hoped. “A lot of people were pissed off. They asked us why we were killing trees. It was really embarrassing.”

Still, Josh doesn’t mind screwing up, even when he does it in a big way in front of his employees. “I think it’s actually helpful,” he says. “The team will see it’s OK to make dumb mistakes. Because in the process of just trying stuff, you’ll come up with great ideas.”

Sebastian Thrun has taken this same approach at Google X, Udacity, and Kittyhawk. “You would be surprised by the amount of support that you will get from the team if you admit failure. You’re instantly more personable. People will rally around you when you admit you made a mistake.”

![]()

They Are People, Not Machines

Flexibility is everything.

When I started at Salesforce, I was still very young, just 25, and I behaved like it: my weekend sometimes started on Thursday night. Roger Goulart had hired me as a business development manager. His core team gathered every Friday morning, and occasionally, I would show up “a little tired” or “under the weather.”* I’m not proud of this, but facts are facts. Obviously, I was not at my best in those meetings. So how did Roger handle it? I’ll tell you first what he didn’t do. He didn’t haul me into his office and chew me out. And he definitely didn’t berate me in the meetings themselves. Instead, he just moved the meeting to Thursdays.

Roger explained this decision to me recently. It seemed a pretty amazing thing for a veteran executive to do for a wayward pup like me. Here’s what he said: “I was there to make the team stronger, and this was something that was easy to do.” A lot of managers would have come down on me with an iron fist. And, listen, I would have conformed. I liked Salesforce, and I wanted to keep my job. But would that have been the smartest choice for the whole group? Obviously, you can’t have a free-for-all where everyone is doing whatever they want. But if the change is small and inconsequential?

Why not, Roger says. “As a manager, you make bets on people, and then you do everything you can to make them successful. You clear things out of the way, you give them resources, you give them help.”

Many managers don’t operate this way. They act as if they have a fiefdom, and everyone should bow to their will. But that doesn’t always get the best out of people. In fact, it almost never does, especially in startups. “I want folks to be as attentive and involved as possible,” Roger says. “Sometimes you just have to show a little flexibility, so that you get the maximum output from your team.”

INSIGHT

There’s a little trick I learned from Dr. Gene Amdahl, the father of supercomputing. I get emotional just talking about it. One day, I’m working in this hugely successful company, and he comes into the computer room where I’m programming. He didn’t know who I was, but he puts his hand on my shoulder and says, “What you’re doing is super important. You’re the only guy that can do this job. I’m so thankful you’re here.” I’m like, “Wow. This guy believes in me.” If you instill that belief in your employees and let them know how important they are, they give back a thousandfold. It’s not a disingenuous trick. For the vast majority of people, to know that they’re appreciated by somebody that’s seven layers above them, it’s worth a billion bucks.

—Fred Luddy, ServiceNow

Leadership Two Ways

Different types of employees respond to different kinds of motivation.

When Jeremy Bloom started Integrate, he initially tried to motivate his staff the same way he, a former elite athlete, liked to get motivated. “I’m used to being around football players and Olympians, and that’s how I initially led the company,” he says. It worked great with the salespeople. “They have the same ‘go get ’em’ mentality. You can throw a big idea up on a whiteboard, and they’re going to go charge it, right?” But the engineers? Not so much. “They hated me.”

Tien Tzuo, of Zuora, knows why. “Engineers want to create,” he says. “And they want to create things they are proud of.” They aren’t motivated by competition the way athletes and salespeople are. Instead, they want to understand how their work fits into the customer’s life and makes it better. “They get energized by the idea that if they deliver certain features, they’ll have a world-class product that’s being used by thousands, if not millions of people,” Tien says. “That gives them meaning, and it’s where they get their motivation from.”

To learn how to relate to and motivate a wide range of people, Jeremy became a Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) Certified Practitioner. Not everybody has to take such a rigorous step. (He’s got an Olympian’s drive, after all.) But as a leader, you do need to understand that different individuals and groups are energized by different motivations. What works for one person or one set of employees won’t necessarily work for another. Your job as a leader is to adapt your management style to each employee and group to help them succeed in the ways that work best for them—not you.

Sharpen the Contradictions

When there’s trouble brewing, bring it out into the open.

Human beings prefer to avoid conflict. It’s natural. Acrimony isn’t good for business. As a leader, however, you don’t have the luxury of avoiding conflict. When a problem is brewing, you need to get on top of it. Unaddressed problems only grow bigger. It becomes increasingly more costly—in energy, focus, resources, goodwill, and motivation—to ignore them.

Many founders find it tough to address conflicts among their people. Maybe you want to be liked. Or you don’t want the combatants to turn their anger on you. Or you’re just busy and stressed out, and you don’t have the bandwidth for one more headache. So you hope the issue will resolve itself without your involvement. I feel you. I really do. All of this is hard. But bad news my friend: you still have to deal with it. And better sooner than later.

Our first investors, Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreessen, use a strategy they call “sharpening the contradictions.”* It means bringing the conflicts out into the open. Sometimes even provoking them. Because once they’re out in the open, you can start to identify what’s really at the core and then figure out a resolution. “Get it out and then resolve it,” Ben says. “You can’t resolve it when it’s low key. But when it’s a crisis, you can resolve it.” So provoke the crisis. Bring it to a head.

Here’s an example: One year, we hired a senior executive into a C-level role. The executive was a highly respected leader with an amazing track record who’d held the same role at one of our much bigger competitors. We couldn’t believe a person like that had agreed to come work at our little startup. The person could have commanded a position at any giant company and earned a lot more, but they said yes to us. It seemed like a score.

Within a few months, though, something seemed off. The executive’s organization was at a critical juncture, and yet the person didn’t seem to have much intensity around their work. Then the executive left for a three-week vacation in a remote location, with no connectivity—right when we were launching a key product.

If a junior person had performed this poorly, you can bet we would have sat their butt down and had a “difficult conversation.” But with this person, we were scared. We had bet so much on them. The person was clearly gold on paper. Plus, we were terrified of having to start from scratch. C-level searches can take half a year or more.

We eventually accepted that we had to find out what was going on. When the executive got back from the trip, we talked to them about how they needed to put more into the job. A few days later, the executive came back and told us their heart just wasn’t in it. We parted ways and began a new search. It wasn’t fun, and it set us back. But if we hadn’t had that blunt conversation, they might not have moved on until much later. Meanwhile, their whole organization would have been stuck in an eddy, setting us back even further.

Don’t Be a Cowboy

I want to mention Roger Goulart’s mantra, “You win as a team, so don’t lose alone,” again here because it’s not just an important part of your company’s culture. It’s also an idea you have to internalize as a leader. You might be the founder, but you aren’t all-knowing. You’re not any smarter than the people you’ve hired. So when you’re struggling with a problem, remember to ask for help. Ask your team. Ask your board members or investors. Ask other founders.

The more you model this behavior, the more comfortable the rest of your team will feel asking for help themselves. For example, every sale at Okta is led by an account executive. They’re often competitive by nature—their “cowboy” qualities serve them well in the rough world of sales. But many other people participate in the closing of deals: presales engineers, professional services managers, and executive sponsors all play a role. So while we value our account executives’ competitive fire, we also need them to be able to ask for help when they get stuck. We can’t afford to lose a sale because someone was too proud to collaborate. Having executives at the top, like you, modeling this practice builds a culture that gives everyone permission to do the same. And that helps the whole company win.

![]()

Get Used to Giving Stuff Up

Especially, and most painfully, the stuff you like.

When we started Okta, I was the president and chief operating officer. Also the head of HR. And chief information officer. And chief security officer. And chief financial officer and General Counsel. As we grew, each of those functions also increased in size and complexity, and we needed to bring on people who were experts in those areas. That might seem obvious, but you’d be surprised by how much founders resist giving up the various jobs they have.

I was initially bummed when we hired our first vice president of sales in 2012. It was necessary, of course. This is one of the things Ben told me to do as he mentored us out of our death spiral. But I liked being out with customers. I liked explaining our story and trying to close deals. I worried that giving that up would leave me stuck in a back-office function. I got over it, of course. A year later, I already had a mountain of new responsibilities on my plate. There wouldn’t have been enough time to lead sales anyway.

Over the years, I’ve gotten better at looking 12 months down the road and assessing which responsibilities I currently have that could be offloaded to better experts. For example, we’ve recently started buying other companies. Todd and I ran the first two acquisitions on our own. But it was clear from the beginning that an experienced corporate development executive would be key to doing more of these. We got one on board fairly quickly.

What trips up many founders is that they aren’t willing to let go. In the beginning, you have to do everything yourself, and you enjoy many parts of it. Maybe you enjoy the intellectual challenge. Maybe you enjoy—or even need—the sense of control. But you rapidly become overwhelmed by the ballooning size of your company, and soon you’re buried under the cumulative weight of all your work.

So here’s my advice: Early on, develop the ability to anticipate when some part of your work is going to get so big that you’ll need to peel it off and give it to someone else. Start the hunt for your replacement six to nine months ahead of that handoff. Resist the fear that if you give away “too many” parts of your job, you “won’t have anything left to do.” Trust me, you will. By the time your new person takes over that part of your work, your plate will be overflowing again.