four

FUNDRAISING

Ithought I knew what I was doing. I had read the business books. I knew the “12 Essential Slides” you needed in any fundraising pitch. I could talk at length about the problem we saw, the solution we offered, the market opportunity, and the competition. But here I was at a famous Sand Hill Road* venture capital firm pitching my heart out, and the guy across the desk was asleep.

Not metaphorically asleep. He’d literally fallen asleep in the middle of my presentation. Needless to say, he did not invest.

It was the summer of 2009. Todd and I were trying to raise seed funding for Okta, and it wasn’t going well. We had pitched dozens of VC firms, but nobody was interested. I want to repeat that to make sure you understand the pain: we’d pitched more than 25 firms, and not a single one followed up.

Sure, we were in the middle of the recession brought on by the financial crisis, but that wasn’t the problem. Investors actually often look for opportunities during downturns. The problem was us. We’d walk in, shake hands, and fire up the presentation. Todd and I would go back and forth, reading from the slides. We followed the format the books laid out. But none of it worked.

The business we pitched then is now worth over $40 billion. It did so well that each of the lead investors in our first four financing rounds made back their entire fund by just investing in our company.† I’m not trying to puff myself up. I just want to drive home the point that the blank stares didn’t mean we had a bad idea. Or that the investors were idiots—far from it. Rather, it was our approach that was failing.

As the summer rolled on, we were running out of options. Then we heard about a new firm that had just opened. We asked for a meeting, and they agreed to see us. It felt like it might be our last chance. On the way to the meeting (and I still remember exactly where we were on Highway 101), Todd told me he was worried we might never raise any money. “What will we do then?” he wondered.

“We’re going to be OK,” I said optimistically. Then I had an idea: “Let’s just ditch the presentation and wing it.”

He glanced at me and nodded. “We have to try something else for sure.”

We parked at the office complex that housed the new firm. A piece of paper was taped to their door. Someone had handwritten the name of the company on it. It felt like we had reached the end of the line of VC firms. But it was all we had.

We walked into their conference room. There was a plastic folding table from Costco and a handful of folding chairs. No flat-screen monitor on the wall. No projector to plug our laptops into. We shook hands as usual, but instead of staying standing up, we just sat down. Todd and I looked at each other. We felt unsteady without our deck. Then Todd took a deep breath and started speaking.

“I guess we’ll just tell you about our company,” he said.

And we started talking. We explained why we felt so strongly about our idea. We had a firm grasp of the details (hashing out the 12-slide deck had served its purpose). But what had been missing in our previous meetings was our passion. We’d never told the story of the company. We hadn’t made it exciting. In fact, we’d done the opposite: we’d put people to sleep.

This time it was different. In part, because we felt like this might be our last chance. It also helped that we weren’t talking like robots. We let our enthu-

siasm shine through, and it made a difference.

At the end of the meeting, those venture capitalists—Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreessen—handed us a $500,000 check. It was our first round of real fundraising.

![]()

Our story isn’t unusual. It’s rare to land an investment on your first pitch. But each meeting is an opportunity to make your pitch better. It took me too long to learn that lesson, so I hope you’ll benefit from the pain I went through. And it’s not just my pain. This chapter is filled with plenty of other agonizingly earned lessons from successful entrepreneurs.

Money is the gas for your startup engine. Without it, the car doesn’t go. For your first 10 years or so, thinking about how to raise money will consume every waking hour. (Okta, for example, didn’t even become cash-flow positive until after we went public.) You’ll get a brief respite the first few weeks after you raise a new round, but then the clock starts ticking again. Rounds are usually designed to last 18 months or so, two years tops. This chapter highlights some of the key things to think about as you go trawling for money.

Note: Everything here is geared toward high-growth startups that raise venture capital. This information won’t necessarily apply if you have a cash-flow business or are self-funding a company that you’re grooming for acquisition.

Ready to Raise?

Before entering the venture capital hunting grounds, study this checklist.

You should start thinking about raising venture capital when you’ve reached a point where you think you’ll be able to grow your company—and its value—to 10 times (10×) its current worth within 10 years or less. That is an extraordinary goal to achieve. So why do you have to aim so high?

Because the money VCs invest actually belongs to other organizations, such as pension funds, university endowments, and foundations. Those entities know that investing in startups is risky. They typically allocate about 10 percent of their assets to what are known as “alternative assets,” which includes private equity, of which venture capital is a subset. Even though they know startups are risky (and that most will fail), they expect that a VC fund’s failed investments will be more than offset by “outsized” returns from the few companies that do well. That’s why VCs aren’t interested in companies that only have the potential to grow two or three times their current size. They need ambitious companies with the potential for giant success—the Facebooks, the Teslas—to compensate for the Juicero-like outcomes in their portfolios. (Google it.)

Here’s a checklist to help you decide if you’re ready to start raising money:

![]() Do you have an idea that is so promising, and whose total addressable market (TAM) is so big (meaning it starts with a $B) that your company could in fact grow 10× quickly, and then, hopefully, 10× again?

Do you have an idea that is so promising, and whose total addressable market (TAM) is so big (meaning it starts with a $B) that your company could in fact grow 10× quickly, and then, hopefully, 10× again?

![]() Do you have your entire founding team in place? Will a firm look at your team and say, “Yes, these are exactly the people we believe can make this happen”?

Do you have your entire founding team in place? Will a firm look at your team and say, “Yes, these are exactly the people we believe can make this happen”?

![]() Do you have material evidence that your idea is a good one? In some cases, if you’re already selling, you’d want to see sales traction. In other cases, it could be a mountain of enthusiastic feedback from your prospective customers.

Do you have material evidence that your idea is a good one? In some cases, if you’re already selling, you’d want to see sales traction. In other cases, it could be a mountain of enthusiastic feedback from your prospective customers.

![]() Have you crafted a story around what your company is about and why it will succeed? Can you tell it persuasively at the drop of a hat?

Have you crafted a story around what your company is about and why it will succeed? Can you tell it persuasively at the drop of a hat?

![]() Do you have a realistic business model?

Do you have a realistic business model?

![]() Are you prepared to do nothing but this for the next 10 years? No vacations. No weekends. Missed birthdays. Sleepless nights?

Are you prepared to do nothing but this for the next 10 years? No vacations. No weekends. Missed birthdays. Sleepless nights?

IF YOU ANSWERED YES TO EVERYTHING, CONGRATULATIONS. YOU’RE READY TO START RAISING.

![]()

Roadmap to Raise

How to stack your pitches.

I recommend a pretty straightforward strategy for running a fundraising process: identify your 15 favorite VC partners (the people, not the organizations), and then approach them in groups of 5, starting with the ones lowest down on your list and working your way up to your top choices.

For example:

WEEK 1 Reach out and set up meetings with firms 11–15.

WEEK 3 Refine and repeat with firms 6–10.

WEEK 5 Refine some more and repeat with firms 1–5.

Here’s why: Crass as it might sound, you’re using firms 11–15 and 6–10 to fine-tune your show. Your meetings with numbers 11–15 will help you figure out what’s working in your pitch and what’s not, as well as give you practice answering tough questions. Use those experiences to refine your narrative (and revise your slides). Your meetings with numbers 6–10 will enable you to see if you’ve worked out all the kinks. Spend this time honing your 60-minute meeting. By the time you’ve completed these 10 dry runs, your pitch should be a work of art. (I hope I don’t have to say this, but don’t tell the first set of firms that you’re using them for practice. The VC industry is a tiny world. People talk. Plus, you might need one of those teams to become your lead investor, if firms 1–5 give your idea a pass.)

Finally, schedule your meetings with firms 1–5. Try to get them scheduled as close together as possible. Your goal is to move through their process—from introductory meeting to second pitch to due diligence—at a fast pace. The final step in this process is the “partner meeting.” It usually takes place on Mondays, and it’s where you pitch your startup to the entire partnership. After you leave, the partners will discuss among themselves whether to invest in you.

In your ideal world, the meetings at firms 1–5 will take place within a few days of each other. That way, you’ll get any term sheets* at around the same time. At a minimum, you want them to come in within the same week. Within a day or two of each other is better, so you can negotiate for the best possible terms. (Term sheets usually expire in 48–72 hours, or, at the latest, “at the end of the week.”) The more of them you receive at the same time, the greater your chances of getting your favorite firm to accept terms that are more favorable to you. What you can’t do is ask a firm to wait another week (much less two), so that you can “see if anyone else is interested.” As much as venture capital is about making money, ego also plays a big role. No one wants to be someone’s second choice.

TKAD: “Time Kills All Deals”

There’s a saying in the sales world: “Time Kills All Deals” (TKAD). It means that you’re more likely to close a deal if you do so quickly, when the customer is at the height of their interest, than to let discussions drag on, allowing cold feet to set in.

The same applies to raising money, which is its own kind of sales process. As such, you need to maintain momentum. As you begin talking to investors, you’ll hopefully notice rising interest in your company. As you move from pitching one firm to another, you’ll sense if they’ve already received a heads-up about you from other investors and whether the interest level is rising. If you’re lucky, that energy will continue to grow during the length of your fundraise. That growing enthusiasm will let you keep moving up the investor food chain and, hopefully, snag one of your preferred VC shops.

On the other hand, if you begin to sense that your momentum is slowing, strongly consider compromising and accepting a term sheet from one of the firms in the 6–15 slots. There’s something ephemeral about momentum: once it starts to dissipate, it can evaporate quickly. And once momentum’s gone, it doesn’t come back. Your number-one job as a founder is to make sure your company always has enough money on hand. Beggars can’t be choosers. A check from any VC is better than a check from no VC. Don’t be left without a chair when the music stops.

How to Vet an Investor

Because it’s not just about the money.

If you should be so lucky as to receive term sheets from multiple VC firms, you should go with the investor at the most prestigious firm or the one offering the biggest check or highest valuation, right? Not necessarily.

Remember, your investors will be part of your life for a long time. The money they bring your startup is only a fraction of the value you’ll get from them. They will (most likely) join your board and become some of your closest advisors. As they say in Silicon Valley, you can divorce your spouse, but you can’t divorce your investor. Plus, your company is your baby. If it goes well, you’ll probably never have another startup. (VCs, on the other hand, get to participate in dozens—or even hundreds—of startups.) So choose wisely.

Here are some things you should suss out in conversations with investors:

• Does the investor have experience in your industry? Those who do can hit the ground running. They’ll have invaluable insights into how the industry works, where the opportunities are, and what risks to consider. They’ll have wide networks they can use on your behalf, whether it’s in making customer introductions or giving you leads on great hires. The absence of such experience isn’t a deal-killer, but it’s not ideal.

• Have they invested in companies that have a similar business model to yours? If so, they’ll be able to help you fine-tune yours and identify any pitfalls you’d otherwise have to discover the hard way.

• Do their strengths balance out your weaknesses? If you are great at product development, you might want to look for investors with sales backgrounds. If you’re great at marketing, you might want someone with depth in engineering. It’s like putting a sports team together. You want a wide variety of skills. You won’t get very far if everyone plays the same position.

Next, you’ll want to do some sleuthing to learn things investors won’t tell you (at least not directly). Reach out to a few other founders in the investor’s portfolio, preferably those whose businesses have struggled—or even failed altogether. You want to find out how the investor handled the challenging times:

• Were they supportive? Or did they ghost the founder when the going got tough?

• Did they find ways to help? Or did they struggle for answers themselves?

• When they had tough conversations with the founder, did they do so respectfully and clearly? Or did they yell and berate? Was it difficult to even understand what they were trying to communicate?

• Did they respect the fact that their role always needed to be that of an advisor? Or did they try to take control and start steering the company themselves?

With all this information in hand, then and only then should you choose which term sheet(s) to accept.

With VC Funds, Size Matters. So Does Vintage.

As I mentioned earlier, the money VCs invest in you comes from their individual funds. The firm’s limited partners (“LPs” in VC talk) put money into a particular fund, and then the fund invests that money in startups. One fund at a firm might do great while another only so-so, depending on which companies each fund bets on.

As a rule of thumb, funds last about 10 years. VCs will spend the first three years of a fund investing half the fund’s money in new startups. (That collection of startups is called the fund’s “portfolio.”) Then they’ll spend the next three or four years using the remaining money to double down on the best-performing startups in the portfolio. The hope is that, during the last three years of the fund, at least one of those companies will have a huge exit event, which is where most of the fund’s returns are made.

So here are two more factors to keep in mind as you’re researching potential VCs:

1 The vintage of the fund.

The fund’s “vintage” means the year in which the fund was started. Your goal is to get backed by a fund with a recent vintage—one that was formed in the last year or so—

so that the VC firm can reward your early performance with more money during those middle three to four years. If you get in at the end of that first period, you might not have enough time to demonstrate how well you’re doing, and you could lose out on any follow-up funding (the “doubling down” money) from the VC.

2 The size of the fund.

Avoid funds that are too large for the amount of money you’re raising. For example, if a fund has $500 million and you only need $3 million, you likely won’t receive their maximum attention—advice and help that could be critical to your success. You’re just not big enough to justify their investing time in you when they have much bigger companies that also need their help. On the other hand, if you get $10 million from a $250 million fund, you can bet you’ll be important to them, and you’ll be more likely to get ongoing support.

![]()

Don’t Change Horses Midstream

Know which partner in a firm you want to work with.

A common mistake founders make is to think of VC firms as regular companies where executives are interchangeable. They think they can approach one partner—maybe because they’ve had a warm introduction to that person—and start selling him or her on their startup. But then, after they’ve made that connection, they ask to be passed to a different partner in the firm, the one they really want to work with. Don’t do this.

Venture firms aren’t companies. They’re collections of individual partners who each build their own portfolios.* These partners also usually have very healthy egos. It doesn’t go over well to establish a relationship with one, only to ask to be handed off to another. If you have a warm connection to one partner but are interested in another partner, go ahead and ask them to introduce you to the second person right at the beginning, before they’ve spent any time on you, especially if you offer a reasonable explanation about why that second person would be the right fit.

Codicil: It’s often useful to get the most senior partner possible in a firm to be your investor. They have more juice to get you both your initial funding and any potential follow-on dollars. In most firms, decisions about who to back aren’t made by some central group. Rather, the partners negotiate among themselves about where their (finite) investment dollars will go. As you can imagine, the further up the pecking order a partner is, the more likely they are to get their way.

True story: I once saw a promising startup lose out on a Series B simply because a more senior partner at their VC firm was having a bad day. The partner who represented the startup (and who was the primary investor on their board) was more junior at the firm. The decision about whether to put money into their Series B came up at a Monday partner meeting. Unfortunately, the more senior partner had totaled his high-end sports car the previous weekend. He arrived at the meeting ornery. The partners were supposed to make investment decisions on two companies, one in the senior partner’s portfolio and the other in the junior partner’s. Three minutes into the meeting, out of nowhere, the senior partner announced that the firm would fund his company but not the junior partner’s. And that was it. End of discussion.

It’s scary to think that the fate of your company could rest on something as capricious as the mood of a VC partner, but it does. In this case, it had serious ramifications for the startup. They struggled to raise any money at all on their Series B, because when a Series A lead investor declines to participate in a follow-on round, other investors suspect there must be a fly in the ointment. The company ended up having to agree to a much smaller round, with bad terms, from a fringe fund. Shortly after, they were gobbled up by a larger company in a fire sale, effectively ending their startup journey.

Keep Your Cool

Get comfortable being uncomfortable.

One day, when Todd and I were trying to raise our Series C (our third major round of financing), we showed up for an appointment at one of Silicon Valley’s top VC firms. We were shown to a giant conference room with one of the longest tables I’ve ever seen. At the far end sat 20 people from the firm, some of whom I had only seen in business magazines. On our side was . . . Todd and me. Talk about intimidation.

Then the firm’s most senior partner walked in. This guy was a tech legend. He’d made some of the Valley’s most historic investments. But instead of heading down to his team, he came over to us and pulled up a chair right next to Todd and me. The man was friendly and relaxed—he even made a few jokes. The entire mood in the room shifted. Out went the inquisition, and in came something much more collegial.

Pitch meetings will always be scary. Why wouldn’t they? You show up, hat in hand, often to a very impressive office, with glass walls and wood paneling, and very expensive cars parked out front, begging for money from people with hundreds of millions (sometimes even billions) at their disposal. They can change your life in an instant. Thorough preparation will help calm your nerves, of course. Revise your pitch deck until it’s bulletproof, and practice answering any and all possible questions until you can deliver answers in your sleep. Research the firm—its partners and staffers, current portfolio, and investment interests—so you can speak directly to the points that will resonate with them.

But no matter how well you prepare, there will always be curveballs. In another pitch meeting, Todd and I arrived to discover that the senior partner—the person we had to woo—was going to dial in by phone. Our anxiety went through the roof. How would this guy be able to absorb everything we needed to communicate? But the meeting went fine. The partner masterfully directed the meeting from afar, and we hit all the important points. Later, the partner even decided to back us.

So be ready for the unpredictable. And when it happens, don’t lose your nerve. Just roll with it. It may turn out better than you think.

Keys to the VC Castle

The four pieces of collateral you need before approaching investors.

THE ELEVATOR PITCH

Imagine you’re in an elevator with your dream investor, and you only have the length of the ride—about 30 seconds—to convince them to meet with you for a pitch. What would you say?

You’re not going to give them a giant spiel. Instead, in 100 words or less, you’re going to tell them something so compelling about your startup that they’re going to be dying to know more. Maybe something about the market and the idea. Maybe something about your performance so far. Be specific. Avoid jargon. Say it so an eighth grader could understand.

Write down your elevator pitch and memorize it. You never know when you’re going to run into a potential investor.

THE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This is a document (a one- or two-page PDF that you can attach to an email or hand out as a hard copy) or a short video (three minutes max) that summarizes all the key information about your company. It should include your big-picture vision; the problem you’re solving; the product or service you’re creating; the names and short bios of your founding team and any key hires; the total addressable market; your business model; your competition; any notable angel investors; and the amount of money you’re looking to raise.

The summary’s job is to whet your readers’ appetite and make them want to schedule a meeting with you. Make sure it’s attractively designed. Like a travel brochure, you want to entice your reader into learning more.

Never send a pitch deck by email. If an investor asks for one, send the summary. If they press you on the deck, they’re clearly interested. Insist on scheduling a meeting if they want to see the whole thing.

THE BUSINESS MODEL

Your in-house business model is a spreadsheet with the detailed financials of your business for the next 24 months: your expenses, headcount, projected sales, and how long you expect the money you are raising will last. The one you give to investors, however, is a simplified version. Just detail how much cash you have left, your monthly (or quarterly) burn rate, your current headcount, and the projected number of customers (or subscriptions, sales, or whatever your key metric is) by quarter for the next eight quarters.

Feel free to add some broad-stroke Year 3–5 ranges for headcount, revenue, and free cash flow to give investors an idea of what your business might look like and how big it could get. You don’t need to have this hammered out in detail. Investors know that a lot of this is technically unknowable. But do make sure you can explain how you arrived at the numbers.

THE PITCH DECK

Most pitch decks follow a standard format. They include slides on: Vision, Problem, Market Size and Opportunity, Product or Service, Business Model, Traction (or other proofs of validation), Team, Competition, Financials, and Amount You’re Raising. Keep it succinct, however. Twelve slides max. No one will sit through a 30-slide deck.

More importantly—and I cannot stress this enough—learn to tell your story without your deck (as Todd and I did when we pitched Ben and Marc). When you’re standing in front of a group of investors, you need to be a storyteller. You need to enthrall them with your vision of where your company is headed in order to persuade them that this is an amazing opportunity and to help them see why you and your team are the only people to tackle this. Once you master this, the slides in your deck simply become the background to your talk.

Lastly, bring hard copies of your pitch deck to leave behind so they can remember your amazing story.

Okta’s Original Elevator Pitch

Business software is moving to the cloud, and businesses are going to need a way to manage their employees’ logins to all those systems. It’s already a big problem, and it’s going to get a lot bigger as companies start running their businesses with online tools. Okta has built the first-ever centralized online “identity management” system. Todd and I helped build Salesforce from the ground up and through its IPO. We know how to build online infrastructure like this, and we’ve already raised $1 million in angel money to start the company. We have 12 employees, 10 customers, and $100,000 in annual revenue, with a clear path to get to $1 million.

Master Your Story

“If you can’t tell something, you can’t sell something.”

“Story is everything,” says Beth Comstock, the former vice chair of General Electric who once ran GE Business Innovations. “If you can’t tell something, you can’t sell something.”

Beth is a master marketer. She began her career as a storyteller, first on public radio and then in television. After joining GE, she quickly rose to become its chief marketing officer. At GE Business Innovations, Beth saw founders make a common mistake when they spoke about the companies and programs they wanted to launch: “I often saw founders and leaders get stuck talking about the ‘gee whiz’ of their technology,” she says. “They lost sight of the fact that they needed to convince their listeners to care.”

Mastering your story is crucial in fundraising, but it will be important in other areas too. You’ll need to tell it to the first employees you try to hire. To customers, especially early ones who take a risk in handing over money to an unproven entity. To the media. At conferences. To potential partners. Even to your own family.

Here’s one winning startup story, as told by Jasmine Crowe, the founder of Goodr, an Atlanta-based B Corporation focused on reducing food waste and solving hunger. I asked Beth to listen to Jasmine’s story and then weigh in on what makes it so effective.

![]()

JASMINE’S STORY

In 2013, I started feeding people who were experiencing hunger and homelessness out of my apartment. I didn’t have a ton of money, but I knew I could cook. I posted on Facebook, “Next Sunday, I’m going to go downtown, and I’m going to feed on the streets, if you want to join me.” I had about 20 volunteers. I made a spaghetti dinner, and I brought out my little Beats Pill speaker. We played The Jackson 5, Aretha Franklin, James Brown, like it was an old-school Sunday dinner. I started renting tables and chairs and linens to give it a restaurant experience. ![]()

Meanwhile, I started researching food waste and got really upset. I couldn’t believe how much food goes to waste, when here I am, putting together $5 donations and my own money, trying to feed 500 people. At the same time, food delivery apps were starting to emerge. I was getting those referral codes for DoorDash, Uber Eats, and Postmates. I started thinking, “There needs to be something like this for restaurants to get their excess food to people in need.”

Then I found out that one of my friends from college, who was well educated and worked in the film industry, was between jobs and struggling with hunger. That was the pivotal moment where I decided I had to go build this app.![]()

I entered into a hackathon that Google for Startups held at Georgia Tech. I began drawing out the little screens of what this app would look like, and I started working with engineers to build it.

The Atlanta airport launched an innovation program where they were trying to become a zero-waste facility. They put out a call for new contracts that could help them get there. I pitched them, saying: “This is the world’s busiest airport. You’ve got over 115 restaurants. At the end of every day, they’re wasting food that could be going to people in the community.” The airport sits in College Park, Georgia, where about 65 percent of children live in poverty. I said, “There’s no reason for any food from this airport to go to waste when there are all these children and families right around your airport who are going hungry.”![]()

The restaurants that worked with us didn’t just get the tax write-off for the donations. We also gave them data about how much food they were letting go. So now they could start to make reductions in their food production, which helps them save money on food costs. We started with one concessionaire who had about 25 restaurants. At the next concessions meeting, they told the others, “We’ve gotten all this insight, and we’ve saved $80,000 in three months.” That encouraged the other concessionaires to sign up too. ![]()

![]() The founder is part of the story. The fact that Jasmine started this on Sundays, played The Jackson 5, and had spaghetti dinners—I’m never going to forget that about Jasmine and her passion. Already, it’s telling me about her.

The founder is part of the story. The fact that Jasmine started this on Sundays, played The Jackson 5, and had spaghetti dinners—I’m never going to forget that about Jasmine and her passion. Already, it’s telling me about her.

![]() The story has to have personal authenticity. Jasmine’s story makes you believe she’s going to get to where she says she’s going.

The story has to have personal authenticity. Jasmine’s story makes you believe she’s going to get to where she says she’s going.

![]() The story should be aspirational. It doesn’t have to be true yet. Founders sometimes get nervous about this. Because while you’re building a vision, you’re also saying, “Help me.” Being open and saying where you’re going, but that you’re not there yet—that truthfulness is persuasive.

The story should be aspirational. It doesn’t have to be true yet. Founders sometimes get nervous about this. Because while you’re building a vision, you’re also saying, “Help me.” Being open and saying where you’re going, but that you’re not there yet—that truthfulness is persuasive.

![]() She’s putting out a vision. Part of what you do with your story is you say, “Here’s where we’re going.” Jasmine’s not just looking to feed people. She’s a productivity solution for businesses. You’re starting to believe, “Wow, Jasmine can make the future.”

She’s putting out a vision. Part of what you do with your story is you say, “Here’s where we’re going.” Jasmine’s not just looking to feed people. She’s a productivity solution for businesses. You’re starting to believe, “Wow, Jasmine can make the future.”

![]()

Secrets to Seduction

Lessons from a founder who raised $10 million from investors.

Ilya Levtov, who’d previously worked at Goldman Sachs and at the VC firm Venrock, launched Craft.co in 2014 to produce machine learning–

generated intelligence for customers. Raising money was hardly a cakewalk. “I probably pitched a hundred different people before one said yes,” Ilya recalls. Eventually though, he was able to bring in a $10 million Series A. So how’d he do it? Here are three key points he learned about making his case:

• Paint a picture of the amazing future—and the giant payout—that awaits. “My days in VC taught me that a big driver for closing a deal was the idea that there could be a huge outcome,” Ilya says. “Not big, not really big, but absolutely huge.” Venture firms need those huge home runs to deliver the necessary returns to their backers. “Tony Sun, one of my bosses in VC, had this phrase he would use to interrogate any startup that came in: ‘What’s the glimmer of greatness?’” Ilya explains. The founder’s pitch is supposed to make an investor squint their eyes and see, way off in the distance, a $10 billion publicly listed company with $500 million in revenue. As you put your pitch together, figure out how to convey that “glimmer of greatness” waiting on the horizon.

• Use analogies. Even investors often struggle to visualize where you’re headed. “You’re trying to construct an argument about why this thing that doesn’t exist yet, could exist—or, even more—will exist one day,” Ilya says. Analogies help bridge the gap. It’s why you often hear startups described as “the Uber for . . .” or “the Airbnb of. . . .” In Ilya’s case, he compared Craft.co to Zillow and Trulia—but for companies. “I said, ‘Look, this thing already works in this domain. The bet we’re making is that a similar thing could work in our domain.’”

• Be enthusiastic. “People like positive energy,” Ilya points out. “Enthusiasm can get people excited enough that they say, ‘I don’t actually know anything about what that person is talking about, but I’ll give them another meeting just to learn more.” Of course, you also need a rigorous analysis and a persuasive argument. And you shouldn’t fake feelings. If you’re not a naturally bubbly person, don’t pretend to be one. Convey your excitement in a way that feels natural to you.

I’ll add two more insights, from my own experience:

• Use your own words, not buzzwords. Investors respond better when you come across as deeply knowledgeable about your idea, and you can clearly explain your customers’ needs, the pain they’re experiencing, the magic of your specific offering, and the huge opportunity ahead. Focus less on being aggressively sales-y and more on being authentic.

• Recognize that your customers will be your strongest advocates. You’ll give investors names of customers to call, but the best VCs will go behind your back and talk to people you didn’t provide. True story: One VC who decided to back us early on first asked for the names of about a dozen customers. When I later asked how the calls went, he said they were fine, and then added, “What was really valuable were the 32 other Okta customers I tracked down on my own.”

Scrappiness Is Next to Godliness

The art of being undaunted.

One of my favorite stories about fundraising comes from Aaron Levie of Box. When he was a student at the University of Southern California, Aaron and his high school buddy Dylan Smith came up with an idea for a business that would allow people to store and share files online. We take this for granted today, but in the early 2000s, it was still a new idea.

Aaron and Dylan were irritated by the clunky systems they had to use to trade files. So in the summer, they holed up in the attic of Dylan’s family home in the Seattle area and banged out a plan. They reached out to local investors—there were many, thanks to Microsoft riches—but, as Aaron told me, “basically everyone turned us down.” You couldn’t really blame the potential investors. Aaron and Dylan were only about 20 years old, and they looked like they were about 12. “Any professional investor ran for the hills,” Aaron says.

INSIGHT

When a founder pitches us, they think we’re evaluating the business opportunity, which we are. But we’re also evaluating you. Your ability to convince us is a proxy for your ability to sell something to someone else. Can you convince people to come work for you? Can you convince customers to use your product? Can you convince a whole slate of people—other than us—to believe in you?

—Marc Andreessen, Andreessen Horowitz

At one point, they tracked down Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen’s home address. They printed out a copy of their business plan and left it at Allen’s front door. But they got crickets in return. Meanwhile, they also looked up Microsoft’s main fax number—yes, fax (they were still commonplace in the early 2000s)—and sent a copy of the plan to Bill Gates. More crickets. Undaunted, they were able to find an email address for Mark Cuban, who was not yet a Shark Tank judge but was a well-known entrepreneur who blogged prolifically about startups. They sent him a copy of their business plan and, to their surprise and delight, back came a check for $350,000.

Just like that.

Here’s what I like about this story: Founders have to be scrappy. To many people, Aaron and Dylan had no business asking people for hundreds of thousands of dollars. But that didn’t stop them. They knew they had a great idea, and they didn’t care how ridiculous they looked faxing Bill Gates at a generic number. And look where it got them: enough money to drop out of college and start building their company. Sixteen years later, Box is worth $4 billion.

Collusion Actually Happens, But It’s Hard to Prove

Never tell a VC who else you’re talking to.

In the United States, price fixing is illegal. Companies are prohibited from joining forces and deciding collectively what they will charge for a specific product or service. This applies to venture capitalists as well. They’re not allowed to decide among themselves how much your company is worth and how much they’re going to pay for a piece of it.

But do they? You didn’t hear it from me, but let’s just say it’s been rumored to happen.

Your goal, as a founder, is to avoid having VCs do this to you for the obvious reason that it works to your detriment. So how do you prevent it? By not telling investors who else you’re talking to. That’s the only way they’d know who to confab with.

Inevitably, of course, an investor, or two or three, will ask who else you’re talking to. They’ll make it sound like a casual question, and you’ll feel awkward about dodging it. So let me give you the magic words to say in that moment: “As you might imagine, other fine firms.” That’ll do more than simply get you out of an awkward pickle. It will also signal to your questioner that you’re aware of the game being played. They’ll back off.

Don’t worry that it will hurt your chances with them. They’ll actually respect you for being clued in. And if they’re genuinely excited about your company, they’ll write a check either way.

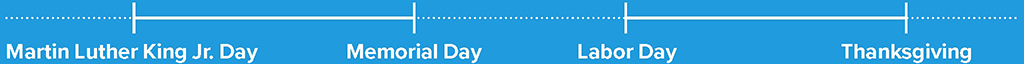

It’s Raising Season!

There are two preferred “seasons” to raise venture capital:

Try to kick off your search for funds either in late January (around Martin Luther King Jr. Day) or in early September (after Labor Day). People go on vacation in the summer, so it’s hard to get enough partners around the table to sign off on a new deal. As for the end of the year, everyone loses momentum around the holidays. These recommendations aren’t set in stone, of course. You’re welcome to start anytime. But if you have the flexibility, use these dates as guides.

![]()

A Million Ways to Say No

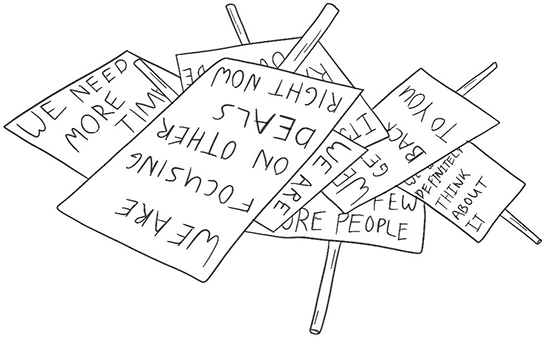

Venture capitalists who decide not to fund you are like the date who won’t tell you they’re not into you. Few investors will ever turn you down outright. They might reply to a pitch by saying, “We’re in between funds.” (Even though they did listen to your pitch and might even have started to do due diligence, which usually only happens when there’s money on the table.) They might tell you, “We need more time.” They might say they need to talk to more people or that they’re focusing on a few other deals right now. They might say, “It’s Tuesday and it’s raining.” Whatever they say, it all adds up to the same answer: No.

In their defense, VCs don’t intend to string you along. It’s human nature to avoid rejecting people directly. More than that, though, VCs are terrified of burning bridges. They live in FOMO. If you suddenly become a hot commodity, they want to keep the door open so they can get in on this round or your next one.

So keep this in mind: Time, as I’ve said before, is your most precious asset. Don’t waste time wondering if a firm is really into you. As with dating, you’ll know if they are. They’ll invite you for a meeting and then another, and eventually you’ll pitch to the partners.

But if you’re getting evasive answers and happy talk but no action, put them on the back burner and move on.

How Underrepresented Founders Can Unstack the Deck

Five ways to fight implicit bias.

Fundraising is never easy, but research has shown it’s generally harder for women and people of color. I’m fully aware of that. While Todd and I struggled to raise money, the fact that we’re both white men who attended schools like Stanford, MIT, and CalTech undoubtedly eased our path in innumerable ways, such as helping us get in the door to make a pitch in the first place.

Much has been written about cognitive biases in the venture community and how they may influence who gets funded. Many venture capitalists rely on two factors to reduce their sense of risk, even if they’re not always conscious of it: warm introductions and pattern recognition. These appeal to a person’s primal, risk-averse lizard brain. Someone who is introduced to you by someone you know has “social validation.” Someone who has no connection to you is an unknown quantity. That’s why warm introductions help a great deal, even though they’re vastly unfair to those who aren’t already plugged into the right networks.

“Pattern recognition” just means you use your knowledge of the past to predict the future. Consider driving, for example. When you first get out on the road, you pay attention to everything. After a while, pattern recognition helps your brain learn what it can safely process in the background (regular flows of traffic) and what it needs to bring to the forefront, so you can act on it (a child running into the road). When founders walk through the door who seem similar to other founders who’ve been successful, VCs might be more open to their pitch. When founders seem very different, VCs sometimes have more questions.

Much of venture investing depends on gut instincts. While investors crunch a lot of numbers, in the end, as with the stock market, they’re really just making educated guesses about who’s likely to succeed. To overcome this built-in fortress of unconscious bias, consider these tips:

1 Research your audience. Look for ways to create common ground. Maybe you attended the same university or graduate school as an investor you’re pitching. Maybe you’re from the same hometown. You might have common interests or hobbies. (Troll social media for clues.) All of this helps move you away from being an “unknown quantity” and toward something more familiar.

2 Highlight attributes that give you credibility. Foreground clearly recognizable signs of authority: your educational degrees, the companies you’ve worked for, the positions you’ve held, any awards you’ve received—whether at work, in school, or even in sports. And finally, highlight the people in your network who are credible to your audience and who can vouch for you.

3 Turn to the whisper network. Women founders who have raised money before you, Black founders, Latinx founders—they will know which firms have better track records with underrepresented founders and which ones might not even be worth contacting. Plug into those networks. They will save you time.

4 Anticipate their questions and master your responses. Research has shown that investors are more likely to ask male founders about the opportunity for gain in their business, while women tend to get questions about how they’ll protect against loss. The difference in framing almost dooms women from the start. What investor wants to park their money with someone they’re afraid will lose it? There is a way around this, however. Research has shown that when women pivot their answers to discuss the opportunity for gain, they end up raising more money.

5 Become a master of body language. I hope you have nothing but great experiences with investors, but odds are there will be at least a few downers. Some investors think it’s their job to be aggressive and to attack pitches or even the founders themselves.* Learn to not let this rattle you. Instead, always project confidence, enthusiasm, and unbeatable energy. Investors notice nonverbal cues, such as body language, facial expressions, and vocal affect, even if they’re not conscious of doing so. Whiffs of dejection can make them question your ability to handle the rigors of startup life, while watching someone take a blow without batting an eye often impresses them.

Don’t Raise Money for the Heck of It

Or to save your butt.

Venture capital is strategic money. You raise it to help you achieve a specific goal that isn’t attainable with the money you have in the bank, combined with your future expected revenues. For example, you might want to enter a new market. Or you might realize it’s time to begin working on a new product that doesn’t currently have demand, but will in a few years. Those are legitimate reasons to seek investment because those projects will help strengthen and solidify your company.

Here are a few reasons not to try to raise venture capital: because you’re flailing, because you haven’t figured out your business model, because you’re burning through your existing cash without showing any results.

If you aren’t running your company well, venture capital won’t help. It will just prolong the problem. It’s like giving money to someone who hasn’t demonstrated the ability to make sound financial decisions: The money just allows them to continue making bad choices. Similarly, money can’t fix what’s wrong with your company. It only amplifies what’s already there.

If things are going well, if you’re firing on all cylinders, if you have a well-run operation, an infusion of outside funds accelerates your growth. If things are going poorly, if your organization is dysfunctional, if there are fundamental issues you’ve avoided addressing, new money just allows you to continue avoiding your issues. It doesn’t solve your problems. It only exacerbates them. So do a gut check when you start thinking about more money. If there are internal problems that you haven’t dealt with, fix them first.

![]()

In Defense of Bootstrapping

Because venture money isn’t always the solution.

Amy Pressman and her husband and cofounder, Borge Hald, didn’t plan on bootstrapping Medallia, the startup they founded in 2001. Like most new companies in the heady days of the late dot-com boom, they envisioned fueling their business with venture capital.

But then 9/11 hit. Medallia had been created to give brands real-time insight into their customers’ experience, and hospitality was one of their first target industries. The terror attacks all but shut down that sector, while also obliterating the venture markets. “9/11 took all the air out of the internet bubble,” Amy says.

They were forced to get very lean very fast. “We’d sold our house, and we were living off our savings,” Amy adds. Everything had to be scaled back: the size of the product, their staff, their operating costs.

The enforced scrappiness ended up having a silver lining: Medallia built enough traction with customers to survive on its own for 10 years. Along the way, Amy discovered something that’s not always widely understood in the startup world—selling to customers took the same amount of time as pitching investors. And after a sale, they still owned as much of the company as when they’d started, which would not have been the case if they’d been getting their money from VCs.

Medallia only turned to the capital markets in 2011, when the emergence of social media meant they had to rapidly expand their product in new directions. By then, the company was doing so well, they ended up getting term sheets from five of the six firms they pitched, giving them a lot more leverage to gain favorable terms. In 2021, the company was sold for $6.4 billion.

Here are Amy’s five key tips for bootstrapping:

1 Find prospective customers who are really into what you’re doing. “If you can’t do that, then you probably need to find a new business.”

2 Stay close to your customers to learn not just what they need but what they’re willing to pay. “You don’t want to spend a ton of time on products that people don’t really want to pay for.”

3 Know that overseas developers can lower your costs, but it helps if you have local knowledge. Medallia worked with teams in Norway (where Borge is from) and Argentina (where their head of engineering was from).

4 Expect to still face competition when hiring overseas, especially from big companies like Google and Facebook. You won’t be able to compete with them on salary, but you can compete on the quality of work you offer. At the big companies, overseas developers rarely get the juicy projects. But at your company, they will be integral to the main efforts.

5 Get creative when hiring locally. Medallia found great hires among women returning to work after having children, veterans getting out of the military, and spouses of international graduate students, who often have work permits.*

Don’t Forget Your Angel Investors

Bring them along as you grow.

When you first launch your company, you will probably need to turn to angel investors, those high-net-worth individuals who help startups get off the ground.*

You pitch these informal networks the way you’d pitch a VC, so they can learn about your company and decide if it’s a good bet. But, unlike at a VC firm, angel-investment decisions are made on an individual basis. You don’t have to convince everyone in the network. Just enough people to make your nut.

As startups get bigger, some founders begin to overlook their angels. If you’re lucky enough to make it to a Series A and then a Series B, you’re going to be dealing with VCs who don’t want to share the wealth; they want to keep the entire round for themselves. It’s understandable. Their decision to back you might be based on an internal goal to own a certain percentage of your company (often 10–25 percent, depending on the round and the firm). They don’t want to parcel out any of that equity to other players.

And yet, it’s in these later rounds where the real money is made. Your angels might have invested early on with a convertible note—a form of debt that converts into equity at a later date—but the value of that early equity is diluted with each additional financing round. As your company shows increasing promise, some angels might want to put additional money into subsequent rounds as a way of maintaining their ownership stake in the company (called “pro-rata”), which means they’ll get higher returns if the company has a successful exit.

This is the point where some founders make a shortsighted mistake—and leave their angels behind. They might be too intimidated to stand up to their new VCs and advocate for their angels. Or they might suffer from Shiny Penny Syndrome and be more excited about the new VC than the dentists and real estate developers who wrote the “friends and family” checks when no one else would. The angel investors served their purpose, and now their services aren’t needed. Many an angel has called up a founder at this point, looking to get into the new round, only to be turned down.

But here’s what that founder is missing: angels didn’t simply write checks that enabled you to get off the ground. They recommended you to other investors. They answered your calls when you needed advice. They introduced you to potential customers or gave you leads on great hires. And now you’re going to cut them out once there’s real money to be made?

While I often remind entrepreneurs and colleagues that “it’s not called show friends; it’s called show business,” it’s still important to remember that angels are the people who made your company possible. These are the people who bet on you. They’re the ones who believed in you. In Silicon Valley, they say, “Life is long, and the Valley is small.” In such an insular sandbox, you want a reputation as a person who treats other people well. So make it a practice to reach out to your angels when a new round is on the horizon, and then advocate for any angel who wants to join in. Their checks will barely be a rounding error to your VC. You might get pushback, but the best VCs will understand, and most will accommodate you.

![]()

You’re Flush, Now What?

Save your nest egg—except for these five things.

You closed your round. The money’s in your bank account. Congratulations! You’re on your way. Time to put all that green to good use, right? Sign the office lease with the skyline views! Invest in some high-end furniture! Call the catering companies! Bring on a yoga instructor and give them stock options! Right???

Wrong!

It’s easy to get dazzled by that giant bank balance—and other startups’ spendthrift ways. But don’t be fooled. That money is going to have to do a ton of work in the next 24 months, before you have to go out and start looking for more. Stay lean and thrifty. Go crazy only on these five things:

1

A really good, full-time, in-house recruiter. Your company is only as good as the people you have in it. A top in-house recruiter (with stock options to motivate them) will repay their cost many times over.

2

A stupidly expensive espresso machine—seriously. No more productivity lost on staff trips to the local coffee shop. Plus, break areas often spark conversations, which lead to closer relationships and breakthrough ideas.

3

Really nice Aeron chairs. (And footrests for those who want them.) When people are comfortable, they’re more focused. (And they avoid getting carpal tunnel syndrome.)

4

Developer-grade computers and monitors. When your employees have the right equipment, they’re more effective and happier, which drives better performance.

5

Great equipment for people who work from home. Spring for great chairs and monitors, as well as desks, lamps, and chair mats if an employee doesn’t already have them. The more comfortable (and happy) your team is while they’re working, the more energy and ingenuity they’ll bring to their work.

* Sand Hill Road is a thoroughfare in Silicon Valley where many of the tech industry’s top-tier venture firms are located.

† Venture capitalists raise funds, or pots of money, from large institutions like university endowments and pension funds. Then they invest that money in startups. They hope that the companies they invest in will, collectively, do so well that the value of the fund grows many times over. So when I say that Okta made back “the entire fund,” what I mean is that, for example, if a fund had $300 million in it, and the firm invested $30 million of that in us, our company did so well that that $30 million was worth $300 million by the time the fund liquidated.

* Term sheets are a type of “letter of intent” that a VC firm gives you when they want to invest. They spell out how much of your company they want to buy and under what terms. When you accept a term sheet, it means you are agreeing to their terms. The next step is for the lawyers, yours and theirs, to hammer out an actual contract for the sale.

* The term “portfolio” can get confusing because it refers to three different things in the VC world: the companies that a specific partner has backed, the companies that the entire firm has backed, and the companies that a specific fund (within a firm) has invested in.

* Some investors justify this behavior by saying that, since founders will inevitably cross paths with jerks in the course of their jobs, they are testing to see how the founder will handle it. Of course, some of them are just jerks themselves.

* For finding talent in unusual places, Amy Pressman recommends The Rare Find: How Great Talent Stands Out by George Anders.

* Google the name of your city and the words “angel network” to find one near you.