eleven

BOARDS

Back at the beginning of this book, I told you how Ben Horowitz gave me two tactical pieces of advice that ended up saving our company. The first, which I talked about in Chapter 3, was that I couldn’t do multiple important jobs at the same time and still do them well. Now, I’ll talk about the second piece of advice. In 2011, as I discussed earlier, our sales were cratering. The small and medium-sized businesses we were targeting didn’t need what we had built. We had started with them because we thought we needed to create a healthy foundation with those customers before we could go after big enterprise companies, which were our real target. Ben was the one who told us that our approach was flat wrong.

This is the power and importance of a startup’s board of directors. They should be able to see what you don’t and, in cases like this, let you know when you’re headed off course.

The Okta platform has a wide range of functionality today, but when Todd and I started, we only had a couple of products, one of which helped companies onboard and offboard employees. This process gets more complicated—and therefore more painful—the bigger a company gets. Ben pointed out that smaller companies didn’t really feel this pain, so they weren’t biting. Big companies, however, experienced this problem, and they would leap at our solution—if we could figure out how to reach their decision makers.

Ben was right. But we didn’t have any experience pitching those big companies. With their thousands of employees, we didn’t know how to identify which executives to target and how to approach them.

That’s when he reminded me of the first piece of advice: you need to hire people who can do what you can’t. So we quickly recruited a new sales team and shifted our attention to these larger companies. Within a few months, our sales ticked up, and within the year, we were seeing exponential sales growth. We had survived because of our board.

![]()

Founders sometimes think of boards of directors as committees to whom they make periodic presentations. You show up and run through your slide deck. The directors ask some questions, and then you all recess for coffee.

That’s not it at all. Board members are strategic partners who, at their most valuable, lend their expertise so you can make the best possible decisions.

In Chapter 4, we talked about how you should be thoughtful about whose money you take because you’re not just taking their money. You’re also bringing them on as a board member, and thus as a key advisor. In this chapter, we’ll discuss what makes for a strong board and what kinds of people you should seek to serve on yours. Many board members will end up being with you for 10 years or more. You need people who are raring to go the distance—and will be effective in helping you succeed.

For help with this topic, I turned to three of Okta’s board members, all of whom have extensive experience serving on startup and corporate boards: Michelle Wilson, a former senior vice president and general counsel at Amazon; Shellye Archambeau, the former CEO of MetricStream, which creates corporate compliance and governance tools, and a director at Verizon and Nordstrom; and Pat Grady, a partner at Sequoia Capital, who has served on over 20 startup boards, including those of Zoom, HubSpot, and Qualtrics.

![]()

Boards 101

The basics you need to know.

A board’s primary responsibility is what’s called “governance and oversight.” Board members represent shareholders*—the collective owners of the company. When the company is still private, these responsibilities are mostly focused on making sure its executives are making the best possible strategic decisions that will enable it to grow. “The board’s job is to enhance shareholder value and make sure the company is thinking about all its constituencies in a holistic way,” says Michelle Wilson.

It’s also a way for venture capital investors to keep an eye on their investments. They want to know which companies in their portfolio are doing well—and therefore should be discussed at partner meetings so that money is reserved to invest in follow-on rounds—and which ones are in trouble.

Later, after a company goes public, there are rules companies must follow, which are enforced in the United States by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The board helps ensure the company adheres to those.

Who’s on the Board?

The composition of the board will evolve as you grow.

WHEN YOU FIRST LAUNCH In your company’s infancy, the board is composed of just you and your cofounders. It’s less of a board and more of a technical mechanism through which a number of activities must take place, including the awarding of shares and decisions about executive compensation.

WHEN YOU FIRST TAKE INVESTOR MONEY The board consists of the CEO (who usually serves as the chairman) and possibly a second cofounder (if it makes sense), along with partners from one or two of the firms that invested in you.

WHEN YOU GET BIGGER (POST–SERIES B) You will start adding independent directors—people who aren’t investors (hence: “independent”)—who have skills and experience that will be particularly useful as you grow.

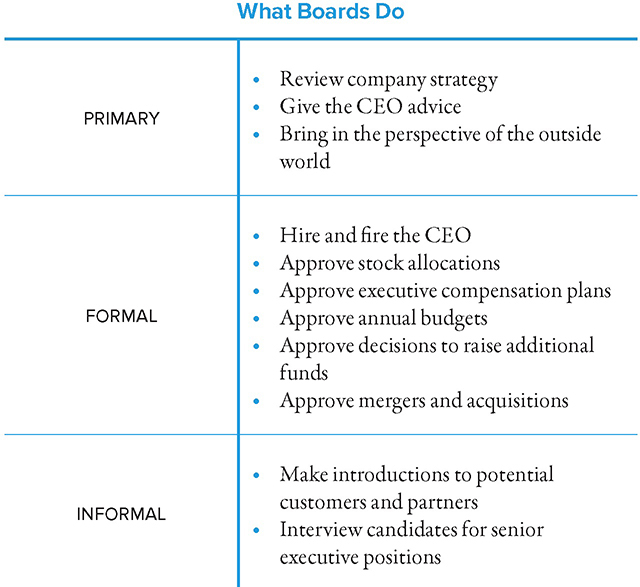

What Boards Don’t Do

• Force the CEO to follow any particular strategy

• Do any of the day-to-day work or management

How to Build a Strong Board

Think Marvel’s Avengers.

Who’s on your board is as important as who’s on your executive team. My friend Alex Asseily, formerly of Jawbone and now cofounder and chairman of Elvie, a London-based femtech startup, compares them to Marvel’s Avengers. Each board member, he says, should have their own superpower. Together, the team should be able to tackle any problem. So give a lot of thought to the investors you take money from (they’ll usually put someone on your board) and the independent directors you add separately. “You want people who are there for the right reasons—who want to help build the company—not so they can add to their résumé,” says Michelle Wilson.

LOOK FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE PASSION FOR YOUR VENTURE

You want people who are constantly thinking about your company, sending you links to articles, talking you up to other investors, and putting in that extra effort in finding solutions to your problems.

BRING ON DIRECTORS WHO UNDERSTAND THE “OLD” WORLD

Founders sometimes steer clear of veterans in the space they’re trying to disrupt, for fear that their old-school mindset will hold back the company’s 179thinking. But these folks know where the constraints and obstacles are. You don’t have to take their advice about the future, but you do need their insights about the present.

HAVE AT LEAST ONE PERSON WHO’S RUN A COMPANY SIMILAR TO YOURS

Your board can only offer you really good advice if they actually understand the space you’re in. If you are building an enterprise company, have someone on the board who’s built an enterprise company before. If you’re building a consumer company, bring on someone who’s steeped in consumer products.

BRING ON DIRECTORS FROM DIFFERENT BACKGROUNDS

Inclusive boards are stronger at problem-solving because they bring a wider range of experiences and insights to the issues you face. They can tap a wider range of networks when it comes to hiring, and candidates will be able to see from your board demographics that your company values a wide variety of people.

BRING ON PEOPLE WITH FUNCTIONAL EXPERTISE

“You probably want one person who knows ‘go-to-market’ so your sales and marketing team have somebody they can bounce ideas off of,” says Pat Grady. “You also want somebody who knows about product development and technology, so your product and engineering teams have somebody to run ideas by. And then you want someone who’s been a CEO to help you as CEO.”

DON’T HIRE YOUR FRIENDS

You need people who will ask hard questions and give tough feedback.

DON’T BRING ON PEOPLE WHO CAN’T STAND EACH OTHER

Vet potential board members to find out if they have any issues with your existing directors. Tension between directors is a net negative.

AVOID PEOPLE WHO AREN’T WILLING TO HAVE DIFFICULT DISCUSSIONS

You can have the smartest people on your board, but if they won’t level with you, they’re not much use. There are any number of reasons why a director might hold back. Sometimes they’re just spread too thin in other areas of their life. Sometimes they’re more interested in preserving a relationship with a more senior person on the board (to maintain access to other good deals, for example). Either way, do your due diligence to make sure that your directors will bring their full energy and voices to your table.

DO DUE DILIGENCE ON EACH PERSON

For every potential director—including investors you’re considering taking money from—find three founders who had that person on their board and whose startup ran into serious challenges. Then ask those founders how useful the director was. They will let you know whether a director has the drive, focus, and seriousness to help you through your most challenging times.

How to Work with Your Board

It all starts with the meeting agenda.

There are two main ways you’ll interact with your board: during your periodic board meetings (perhaps monthly at first, but eventually quarterly) and in discrete situations in which you tap them offline for advice or help. What follows are ideas for how to get the most out of both cases.

![]()

During Board Meetings

Board meetings aren’t about show-and-tell. They’re about getting help on your most important and pressing issues. These practices will help:

• Send out the agenda a week in advance. It’s your responsibility, as chairman, to set the agenda. Send it out far enough ahead that the board has time to get up to speed. Remember: Information that is old hat to you will be new to them. They need time to absorb it.

• Focus the meeting on your most important strategic issues. A mistake new founders make is to use the board meeting to provide a general status update. That doesn’t help you, and it’s not particularly interesting to your directors. What they want most is to tackle problems or figure out strategy. So think of your board meetings as working sessions where you’re going to hash out one to three (but no more—there won’t be time) issues your company is currently struggling with. Use the first part of the meeting to quickly run through the big picture, then dedicate about 45 minutes for each issue with which you need help.

• Don’t bring in a stream of executives to present updates. Founders sometimes let their executives present to the board—both as a reward for great work or as an opportunity to get experience working with boards. Don’t do this. It sucks up time and hampers your ability to focus on the most strategic challenges.

• As the company gets bigger, cull the slide deck. Founders often get in the habit of filling out the same templates for each meeting. As the company grows, they add new slides for new parts of the business. Before you know it, you have a 50-slide deck. Cull it! “Curating the deck is as important as curating the conversation,” Pat Grady says. Make it a habit to cut slides that have receded in importance. “Unless you make a deliberate choice to stop talking about something, you’ll fall prey to inertia,” he adds.

• (Optional) Write a narrative about each of the strategic issues. The primary document for most board meetings is a slide deck. But isolated pieces of data or short bullet points don’t communicate nuance and complexity. If you feel so inspired, sit down and write a three- to five-page summary of at least one (if not all) of the issues you’re struggling with, and send it to the directors along with the deck. I’ve seen this work very well for Todd. It gives the board a clear sense of the most important things on his mind. “A written narrative really crystallizes what you thought of those data points and what is concerning you as the person running the business,” explains Pat. “It’s also a way for you to make sure you actually understand the issue and that you’re prepared to discuss it.”

![]()

Outside of Board Meetings

You can contact board members outside of formal meetings. Most directors are fine getting calls from founders who need help with something in the director’s wheelhouse. In the early days, when it’s just you and your cofounders, you might find yourself contacting an investor daily. “I don’t think it’s unreasonable to want to be on the phone every single day,” Pat says. “The board member is like a cofounder at that point.” In other situations, when a board member is very busy, you have to be more strategic about when you hit that person up. In all cases, make sure your conversations are tightly focused and that you’re asking for help with something specific. You want to use their time effectively.

![]()

Board Majority Doesn’t Matter

Until it does.

New startup founders often ask me two things: whether they should have an odd number of people on their board (so that there’s never a tie vote) and whether they should make sure that a majority of members are “friendlies”—people who will go along with the founder on important votes.

Here’s what I tell them: Don’t worry about it.

In theory, boards use votes to make decisions. In practice, however, the vote should just be a formality. If you’ve chosen good people and you work well with them, you should all be on the same page. I don’t think that the Okta board ever voted on anything when we were a private company, other than maybe officially confirming financing plans and equity grants.* We generally made decisions through discussion, which is common for startups. If you find yourself with such a deeply divided board that you need to take votes to settle matters, then you have a more foundational problem than the mere number of members on your board.

The only times I’ve heard about startup boards holding votes is when they’ve decided to remove the founder from the CEO slot—and the founder is not going willingly. (Votes also sometimes take place on financing plans that have gotten contentious.) But even voting to oust the founder is rare. Not because boards don’t sometimes need the founder to step down. That happens. But boards usually are able to get CEOs to leave willingly through a mutual (if not always amicable) agreement regarding separation terms. A board vote to oust a CEO is such an extreme move that it often damages the value of the company (especially if litigation ensues), which is something both the board members and the CEO, who still has shares, want to avoid.

Remember, Your Board Isn’t Your Boss

As the CEO, you don’t have a boss. The buck stops with you. You make all the decisions about how to run your company. (Although if you’re a cofounder but not the CEO, then you do have a boss—the CEO.)

A board will never give orders. That’s not their job. Sure, some directors might very strongly suggest that a certain course of action would be a really good idea. But it still remains advice. They don’t have the right to actually tell you what to do. “It’s up to the CEO to internalize feedback and choose which parts of it they want to act on,” says Pat Grady. “After all, the board could be wrong.”

The only way in which the board is like your boss is that they hold the power to fire you and hire another CEO. They represent the shareholders. It’s their responsibility to ensure the company is being run well. If they lose confidence in the choices you’re making, they might decide to cut you loose. “If you’re the kind of person who is motivated by feeling like you need to deliver for someone else, then go ahead and think of them as your boss,” Pat adds. But otherwise, simply think of them as strategic partners who are highly motivated to ensure you get things right.

A Cautionary Tale

The right board for the wrong mission.

Jawbone was one of the most exciting consumer electronics companies on the scene in the late 2000s when it released one of the first high-quality Bluetooth headsets. Wireless earbuds are commonplace today, but back then, they represented newfound freedom from the tangled cords of wired headsets.

Alex Asseily is the first to admit that Jawbone had a lot of challenges. Despite their first-mover advantage, they had to shut down in the late 2010s. One of the mistakes Alex talks about was the composition of his company’s board. It was full of very experienced investors and operators—but most came from the software or enterprise sectors, not the world of consumer technology, much less consumer hardware. “They couldn’t see around those corners,” Alex says. “And that’s ultimately what you want—someone who can see around corners.”

Alex compares building a startup to climbing Mount Everest. “You need someone to tell you how much rope you need or whether you take the crevasse route or the ice sheet route,” he says. “Consumer products are just very different from enterprise products. You have inventory. You have hardware development. It’s much less forgiving if you make mistakes because you ship a whole bunch of products, and you can’t easily get them back” if they’re faulty—the way you can fix bugs with software updates if your product sits in the cloud.

Looking back, Alex wishes he’d brought a few people on to the board who had direct experience with the issues Jawbone faced: brand-marketing experience for consumer products, consumer-product finance and operations, or hardware experience. “It’s really important for founders to understand the kind of business they’re in and then bring on people who have climbed that particular mountain,” he says. “Those are the people who are going to help the most.”

![]()

How to Build Credibility with Your Board

And how to lose it.

In the beginning, your board is going to think you’re amazing. They wouldn’t back you if they didn’t. But that can change once they start working with you up close. You need to maintain your credibility with your directors because they have the ability to go to bat for you when you go through rough patches. They won’t do that if they lose faith in you. And faith, once lost, is very difficult to regain.

Credibility with your board comes down to two things:

1 Honesty. Be candid with the board about the state of the company—where you’re doing well and where the challenges are. It’s natural to want to deliver a rosy picture, but a picture that’s too rosy won’t allow you to get the help you need from your directors. Worse, they’ll see right through it. They’ve been to this rodeo. “If I’ve got to ask a lot of questions to uncover the issues, it makes me wonder what else I don’t know,” says Shellye Archambeau.

2 Execution. If you say you’re going to do something, do it. The board’s role is to make sure the company can grow. The most basic way to believe in the CEO’s ability to scale the company is to see that he or she can follow through. If you fail to deliver on what you’ve promised, the board will question your ability to tackle the even bigger issues coming your way.

On the other hand, one thing that won’t impact your credibility with the board is whether you take all their advice. In fact, doing so might be a red flag. “Nobody knows the company better than you do,” Shellye says. “If a CEO always does everything a board says, I’d be concerned.” Instead, listen to their advice and then process it as you would any other person’s whose experience and insight you value. Integrate their wisdom with what you already know about your business, and then make the best decision for the company.

When Issues Arise

Your directors are members of your team, and when issues arise with a director’s performance, address it the way you would an employee’s (while remembering, of course, that this person is not an employee):

When a director doesn’t seem engaged, but you want to keep them.

If you know a director can be valuable, but they don’t seem engaged—for example, they don’t show up prepared, or they don’t participate in discussions—reach out to let them know you value their participation and ask if there’s 185anything you can do to ramp up their involvement.

When a director doesn’t seem engaged, and you don’t want to keep them.

Sometimes you realize someone’s not a great fit, or they don’t have as much to offer as you’d hoped. In this case, broach their lack of engagement respectfully but directly. “You can just go to them and say, ‘It doesn’t seem like you want to be here. If I’m reading that correctly, would you like to be excused?’” advises Pat Grady. Things may have shifted in their lives, or they simply might not have the time they thought they would. They might actually welcome the opportunity to bow out.

When you want to replace a director with someone else at their firm.

This is tricky. If a board director from a VC firm isn’t cutting it, you might decide that someone else at their firm would do a better job. Whether you’re in a position to ask the firm to make a switch depends on how well your company is doing. If you are one of their top-performing startups, the firm will be motivated to keep you happy and may accommodate you. But if your performance sits in the middle of their portfolio or, worse, down toward the bottom, the firm probably won’t be receptive. (Making a change is a disruptive move for them—egos and all that.) Instead, you might try to find ways to help the board member be more productive.

Seriously, Skip the Board of Advisors

They’re not worth the time and money.

A board of advisors is simply a group of people you can call on for their expertise. They have no role in oversight or governance, as the board of directors does. Instead, in return for some equity, they’re “on retainer” so you can get insights or help on specific issues you’re struggling with. Plus, if they’re particularly famous, their names on your website can help wow potential investors, potential hires, or customers.

On paper, a board of advisors sounds great. My take is controversial: I don’t think such a board is a great idea. Here’s why:

• Advisors aren’t engaged enough to be able to really help. Sure, they’re on speed-dial. But they don’t have the depth of knowledge about what’s going on with your product or company to be able to offer highly useful insights—not without you spending hours on the phone just to get them caught up. Plus, they aren’t always accessible the way your board members are. They squeeze you into their limited downtime, and they sometimes act like they’re doing you a favor. Some even forget that they’re an advisor, and when you call for help, you have to remind them of their commitment. Crazy, but true.

• You pay them a lot for not much return. Advisor arrangements are often just for a single year. Need to talk to Advisor Bob three months after that year runs out? Technically, you’re out of luck—or will have to draft a whole new advisor agreement (often for more equity), which is grating when they still have the old equity that you’re working your butt off to make ever more valuable.

• Advisor shares can complicate your cap table—if they start piling up. The capitalization table (“cap table”) is a document that lists everyone who has shares in your company, along with the many assorted rights they have. Every time you raise a new round, the cap table is updated, based on the agreements with the new set of investors. There’s a lot of complexity in managing a cap table, and advisor shares quickly become vestigial remains of something that once might have been useful but isn’t anymore.

Bottom line: There’s a lot of complexity—and cost—involved in setting up a board of advisors. You’re much better off turning to a network of peers or hiring a particular expert as a consultant. If nothing else, you can always try seeing if someone will talk to you in an isolated case as a favor. Some people are receptive, especially if they can learn from you too. (They might want your front-row insights into customers or industry dynamics, for example.) Just don’t forget to send them a nice bottle of wine afterward.

* At least this is true in the United States. In other countries, boards have responsibilities to other stakeholders as well. This chapter focuses specifically on US boards.

* Now, as a public company, we’re required by the SEC to hold votes. But even so, it’s mostly a formality because we’re able to reach consensus through discussion.