INTRODUCTION

It was July 2011 when I realized I had failed.

I was driving my ailing, 17-year-old Honda Accord down Harrison Street in San Francisco, and the heavy, gray blanket of summer fog seemed to press down on the city, and on me particularly. I considered just heading back to my apartment and not showing up for the meeting. After all, what was there to say? Our business was doomed.

I had started Okta with my friend Todd McKinnon in 2009. It was a pretty simple idea. We both believed business software was going to move online. The days of getting CD-ROM install discs would end soon. Eventually, somebody had to make sure that we could all sign in to software as it moved online. That had to be useful, right?

Todd and I walked into the small conference room at our cramped office where our board of directors was waiting. They had no idea that the news we were going to share would mean they were about to lose all the money they had bet on us. I tried to remember the moment, to lodge those smiles in my mind. Nobody was going to be smiling when we were done.

“OK, well, I’ll dive into the quarterly report,” I said.

I had stayed up all night pointlessly adding slides to the presentation, hoping to soften up the directors with minutiae before coming to the bad news. As I clicked through the data, I could see their attention wandering. There was a slide about hiring. Another about client prospects. Finally, we got to the slide I’d been dreading: sales and revenue.

“Yeah, and so, next, I’m gonna highlight that we hit a speed bump with sales,” I said. “We missed our projections by 70 percent.”

Everybody looked up. That got their attention. They seemed to be wondering if they had misheard me. Perhaps I’d said 17 percent?

I clicked forward, and it was there for all to see. A 70 percent sales miss. Our revenues weren’t going up and to the right like all of our planned projections. They had flatlined like someone whose heart had stopped. Nobody was buying what we were selling.

“You show us a bunch of random sh*t before you show us this?” one board member asked, astounded.

“Let me tell you one thing,” another board member snapped. “This is the kind of presentation that should only be a single slide long.”

Then they told me to get out of the room. They were going to talk to us individually, so they could figure out what was going on. Since Todd was the CEO, they’d speak to him first.

I stepped outside and looked around the office. I was the president and COO. I’d spent two years pouring everything into this company. Now, it was worthless. To make things worse, my wife had just finished her medical residency, and we’d taken on a lot of debt. My stress levels were at an all-time high. I needed some air.

An hour later, I was back in my car, driving aimlessly around the city, when I got a call from Ben Horowitz, one of our board members. Ben and his partner Marc Andreessen had given us half of the $1 million seed money we’d used to start the company. Less than 12 months later, they’d put in another $8.85 million.

“You know that forecasting doesn’t translate into sales, right?” he said.

I mumbled something lame, and he cut me off. I figured he was going to fire me and shut the company down.

Instead, he gave me two pieces of advice. I’ll get into the specifics of what he said in the following chapters, but here’s the upshot: He didn’t tell me to work harder or berate me for being an idiot (though that’s what I felt like). He drew on his own experience as a founder who’d faced near-bankruptcy himself and gave me specific, tactical suggestions for how we could pull ourselves out of our death spiral. It was wisdom he’d learned the hard way.

Too often in business, this kind of knowledge is only shared among a select few. It’s the kind of thing that gets passed person-to-person. And yet, for a founder, it often makes the difference between success and failure. In my case, the advice turned everything around. We immediately implemented Ben’s ideas, and things started to look up. Sales increased, and the business began to grow rapidly. Six years after that fateful board meeting, Okta went public. Today, in the fall of 2021, as this book is preparing to go to press, the company is worth over $40 billion dollars.*

If it weren’t for that advice, at that moment, I don’t think Okta would have survived. It changed the course of the company—and the course of my life.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Several times a week, I get calls or emails from aspiring entrepreneurs looking for exactly the kind of advice that Ben gave me on that gloomy day. They’re looking for real-world, actionable insights, and they’re not getting them from the “Big Idea” business books out there. I read those books—and appreciate them—but when you’re in the trenches, you don’t want generalities. You need to know what to do right now.

That’s what this book provides. Over the past 20 years, I’ve taken notes on the advice I’ve been given. I’ve been lucky enough to meet hundreds of business leaders and investors across the country, and I always pepper them with questions. The nitty-gritty tips in this book represent the distilled wisdom of two decades in the business trenches. It comes from people who have built over a trillion dollars’ worth of wealth for themselves and their investors.

I’ve battle-tested these ideas myself, so I know their power. And I’m convinced it’s long past time to share this wisdom. Entrepreneurs, CEOs, and corporate board members are overwhelmingly people of privilege—mostly men, largely white, frequently graduates of a few select universities, and usually members of difficult-to-penetrate networks. That has to change. Most economic growth—in the United States and abroad—comes from entrepreneurs and the new companies they create. To help more people earn a larger slice of the pie, we need to demystify the world of startups and disseminate the hard-won, closely held secrets of how to grow a business. These lessons should be available to everyone. That’s why I created the Zero to IPO podcast that preceded this book and why I decided to capture all those insights in a single place, here.

Many people go to business school thinking that an MBA will teach them to navigate the world of finance and management. That may be true if you want to work for an established company. But if you want to start your own—if you have a fresh idea for how to solve a problem—then business school doesn’t usually provide a roadmap. I was fortunate to attend MIT’s Sloan School of Management, where I received an MBA in entrepreneurship and innovation. I made many lifelong friendships with classmates and faculty. I took amazing classes, including several on entrepreneurship and tech startups. I also ran MIT’s celebrated $100K Entrepreneurship Competition. But even with all those experiences, I still emerged from business school with a weak grip on what was involved in building a company from scratch. I had to learn that from talking to entrepreneurs who had struggled before me—people I met through social circles in the Bay Area as well as other founders I met through Okta’s investors. In this book, I will present their wisdom and advice.

The chapters ahead will guide you through the key steps in launching and growing a company. While I and many of the people featured in these pages have built public companies, a lot of the advice in here applies to founders who intend to get acquired or just stay private. Only a small subset of companies make it to the stock market, after all. Many founders build businesses that eventually get snapped up by larger corporations. And many more remain private (known as “cash-flow businesses”), throwing off enough money for you and your colleagues to do the work you want and live well. You’ll see that some of the information in here—like how to raise money from venture capitalists—does only apply to the world of high-growth startups. But most of the advice, from how to choose an idea to how to set your company’s culture, is applicable to entrepreneurs starting any kind of business.

![]()

This book is organized by topics in roughly the order you’ll run into them as you build your business. In the beginning, I’ll talk about who should become an entrepreneur and how to tell if you’ve got a good idea. From there, I’ll focus on putting teams together and raising money. After that, I’ll discuss sales and building a company culture, and then how to grow your company and how to lead it. I’ll talk about what happens when everything goes south and how to take care of your mental and emotional health along the way. Lastly, I’ll talk about working with boards of directors and going public.

The material is divided into individual sections, each with its own set of takeaways. Some of the stories in here are my own. Most, however, come from the many founders, investors, and executives I’ve met throughout my career in Silicon Valley. Some of them told their stories on my podcast. Others shared their experiences specifically for this book. Unless otherwise noted, all the stories and quotes in the book, including those from various experts, come from these interviews.

If you’re an entrepreneur who doesn’t happen to live in Silicon Valley, New York, London, Tel Aviv, Tokyo, or any of the other major startup hubs around the world, I want you to know that you too can do this. This book will help you, but I need to level with you: Regardless of where you live, your life will be painful and hard if you follow this path. We tend to think of successful startups as businesses that were bound to succeed while failed companies were doomed from the start. That’s not how it works. In this book, you are going to hear what really makes the difference. This may dissuade some of you from pursuing your idea. Better now than later.

But if you are not dissuaded—if you’re ready to withstand years of doubt, instability, and stress—then welcome to the real world of entrepreneurship.

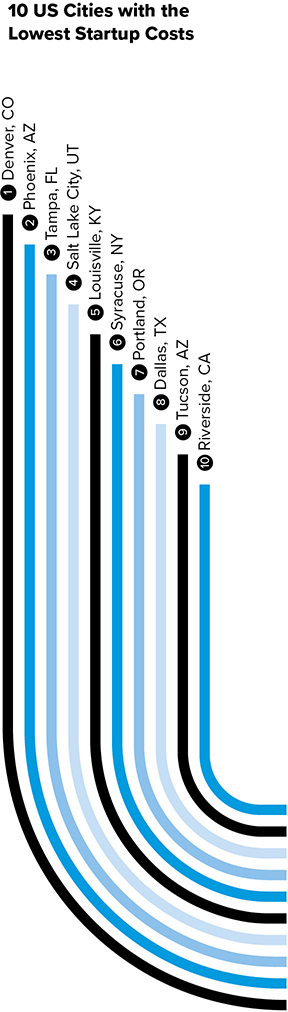

Source: “10 Best U.S. Cities for Startup Costs,” Embroker, October 2021.

Three Rules to Live By

This book is full of great tactical advice, but if you stop reading here, there are three principles I’d want you to leave with, even if you learned nothing else.

1 Time is your most valuable asset.

If you take money from investors (particularly venture capital firms), that money has a fuse on it. The VCs themselves need to produce returns for the institutions that gave them the money to invest in you (pension funds and university endowments, for example). So as soon as you take a VC check, there’s pressure on you to become wildly successful within a relatively short period of time. How long? It depends, but for the purpose of making this point, think at least five to seven years. That means you’re going to have to look at everything you do—from the smallest tactical choice to the biggest strategic decision—through the lens of whether it’s helping you move quickly or whether it’s slowing you down.

2 Keep the main thing the main thing.

Bill Aulet, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, used to remind me of this when I was in business school. It’s so important that I printed it up poster-size and hung it on my office wall. What it means is: prioritize, prioritize, prioritize. Don’t get wrapped up in details that don’t matter. Always stay clear on what the most important thing is—for the next hour, the next month, or the next year. I take this precept so seriously that, more than a decade into Okta, people around the office still hear me asking myself several times a day (out loud), “OK, what’s the main thing I should be working on?” It’s my way of helping myself stay laser-focused.

3 Nothing happens until someone sells something.

This is the second poster on my wall. It paraphrases a remark originally attributed to one of IBM’s first CEOs, Thomas Watson Sr. Sure, rag on motivational posters all you want, but Old Man Watson had it right. When you first start out, you’re going to find yourself dithering over everything from organizational charts to early hiring decisions. But none of that ultimately matters if you never make a sale. The point of your business is to sell your product to customers. Everything else is secondary.

* The valuations of public companies fluctuate with the stock market. All valuations in this book are pegged to each company’s market capitalization on Nov 15, 2021, which was shortly before this book went to press. The valuations of private companies were taken from funding and acquisition announcements.