Maintaining IT Compliance

Simply achieving compliance is not enough. Compliance is an ongoing process that should be treated as a continuous function within the organization. Change is constantly occurring. The following are primary examples of why organizations must maintain IT compliance as an ongoing program:

-

Organizations are dynamic, growing environments. As they adapt and grow, things change and compliance must be assessed against the changes.

-

Threats evolve. Threats to organizations, like organizations themselves, constantly change and adapt. Organizations must respond and adjust appropriately to these threats.

-

Laws, regulations, and industry standards continue to evolve, and new ones are introduced. Organizations are required to exercise due diligence. These efforts evolve as due care rises. What was good enough one day might not be enough the next.

-

Many regulations require annual audits, ongoing reporting, and regular assessments against the environment.

Maintaining compliance requires a well-defined programmatic approach that involves processes and technology. This program needs to be monitored on an ongoing basis. At a minimum, the program should include the following:

-

Regular assessment of selected security controls

-

Configuration and control management processes

-

Change management processes

-

Annual audit of the security environment

Conducting Periodic Security Assessments

Regular security assessments should be part of the ongoing security strategy for any organization. Security assessments provide valuable metrics for maintaining compliance. In general, an assessment should address people, operations, applications, and the infrastructure throughout the organization. Because security assessments are conducted more often than, for example, an annual security audit, the purpose and the scope of a risk assessment can vary widely. Generally, a security assessment is grouped into different types:

High-level security assessment—Provides an overall view of the information systems and is useful when examining across a broader scope

Comprehensive security assessment—Provides a more targeted, concise, and technical review of information systems; involves control reviews and identification of vulnerabilities

Preproduction security assessment—Used for new systems prior to being placed in production; may also be used for systems after having undergone a significant change

In addition to undergoing an initial security assessment, organizations should also determine how often they conduct assessments thereafter. Some of the considerations that should factor into the decision for ongoing assessments include the following:

Expected benefits

Scheduling requirements

Applicable regulations and industry standards

System and data classification

High-impact systems—for example, systems that process or store sensitive information—might require more frequent assessment than those that have a lesser impact. Also, consider when the last assessment was completed, as even a system with a moderate or low impact can present issues if the system has not been assessed in a long time. Often, the ongoing assessment process is driven by an organization’s requirement to demonstrate compliance with regulations or standards.

Performing an Annual Security Compliance Audit

The regular security assessment should be supplemented with annual security audits. Although annual audits of specific functions are required for many organizations, an annual internal audit provides the organization with an independent review of the adequacy and effectiveness of IT security’s internal controls. An audit should never be thought of as a one-time event.

In fact, as with security assessments, organizations have embraced the idea of continuous auditing. An audit completed less than once a year can offer only a narrow scope of the evaluation. This results in not providing real value for the organization. Organizations with an internal audit function are in the best position to implement audits that are more frequent or to put in place a continuous audit program.

Defining Proper Security Controls

The environments of controls are made up largely of a basic set of principles that apply across the various domains. These basic principles are embedded throughout security operations and administration management. These include the following:

Defined roles and responsibilities

Configuration and change management

Environments for development test and production

Segregation of duties

Identity and authentication

Principle of least privilege

Monitoring, measuring, and reporting

Appropriate documentation

When a basic control environment is in place, organizations can begin implementing additional controls to continue reducing risk to acceptable levels. An important aspect of maintaining compliance is defining and adjusting proper security controls. Although there are many different guiding documents for control standards, organizations must be careful of which specific controls they implement and how they put those controls into place.

Selecting and maintaining the right controls requires consideration of completed risk assessments. This risk assessment must address real threats while considering the trade-off between risk and benefit. If you start by implementing controls properly along with proper documentation, then maintaining them shouldn’t be as difficult. On the other hand, it might be easier to become complacent. As a result, organizations might not document the changes to controls and the implementation of new controls after a basic set is in place.

Creating an IT Security Policy Framework

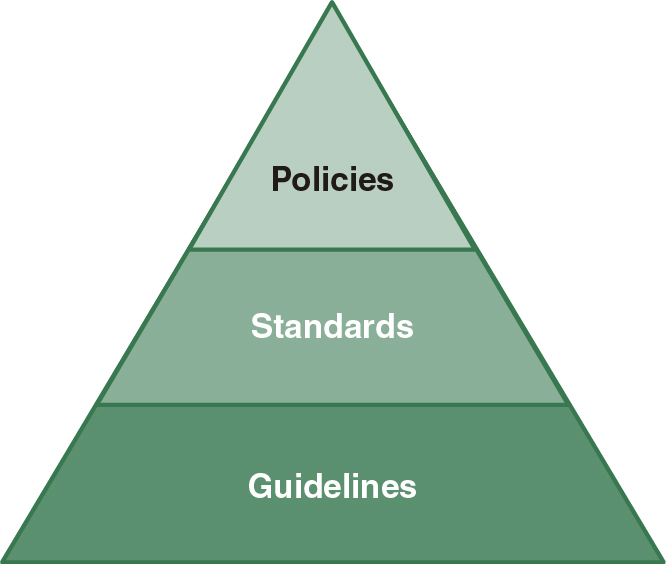

IT security typically falls within an established IT policy framework. To maintain compliance, however, organizations should create a framework for IT security. A policy framework provides for a structured approach for outlining requirements that must be met. The framework can be thought of as a pyramid, as shown in Figure 3-2.

FIGURE 3-2 A policy framework.

The framework starts on the top with very clear and concise objectives or requirements and then continues downward, exposing further details and additional guidance. At the topmost level is the policy. The policy regulates conduct through a general statement of beliefs, goals, and objectives. Next, standards support the policies. The standards are mandated activities or rules. Next, a guideline further supports the standard as well as the policy. Guidelines provide general statements of guidance but are not mandatory. Here is an example of these three components:

Policy—Users are required to use strong authentication when accessing company systems.

Standard—Users are required to use two-factor authentication when accessing the remote network, combining a physical one-time token code with a PIN.

Guideline—Always keep your token within your possession and be aware of your surroundings when entering your PIN.

In addition to these three items, a procedure can also be part of the framework. A procedure provides step-by-step instructions that support the policy by outlining how the standards and guidelines are put into practice.

Implementing Security Operations and Administration Management

Information technology has become a big part of how organizations operate and enables customers, partners, and suppliers to stay connected. This requires the organization to implement and evolve its security and operations management functions to handle rapid change in accordance with stated policies. This added complexity makes it even more challenging to ensure that systems within the organization comply with security policies and standards. Consider that unauthorized changes are prevalent and new vulnerabilities appear daily. In addition, mistakes are bound to happen with the configuration and deployment of new systems. Auditing tools, industry standards, and frameworks provide solid foundations on which to base security operations and administration management.

Configuration and Change Management

Although configuration and change management isn’t typically considered a function of IT security, it is very much related because of its implications with regard to IT security. Configuration and change management is a process of controlling systems throughout their life cycle to make sure they are operating as intended in accordance with security policies and standards. Additionally, configuration and change management involve the identification, control, logging, and auditing of all changes made across the infrastructure.

Change management is typically founded upon baseline configurations defined for systems. Subsequently, it ensures that authorized changes to the system do not affect their security. Additionally, change and configuration management provides a method for tracking unauthorized changes. Changes that are not authorized can negatively affect the system’s security posture. Thus, a process for change and configuration management ensures that changes are requested, evaluated, and authorized. The following represents the high-level process:

Identify and request a change—A need for a change is recognized and a formal request is submitted to a decision-making group.

Evaluate change request—An impact assessment is done to determine operational or security effects the change may have on the system or related systems.

Decision response—A decision typically results in the request either being approved or denied.

Implement approved change—If the request is approved, the change can be implemented in the production environment.

Monitor change—Administrators ensure the system operates as intended as a result of the change.

A review board usually manages this five-step process. A committee of employees from multiple disciplines within the organization makes up this board.