These checklists will help you to keep your project progressing and support you in reaching your end goals. This represents the core day-to-day work of a project manager.

Tracking progress and writing a progress report

To be able to keep a project on track, the project manager has to monitor progress. There are three questions a project manager must be able to answer to be sure the project is progressing as expected:

- For schedule: Is the project progressing at least as fast as planned?

- For cost: Is the project’s budget being spent no faster than planned? (See page 168.)

- For benefits: Are the benefits from the project being delivered at the rate expected?

The last question is only relevant if the project delivers benefit as it progresses and not just at the end.

To track progress against any of these three dimensions you need two sets of information:

- How much work has been completed, how much money has been spent and what benefits have been achieved?

- How much should have been completed, spent or achieved?

Being able to answer these questions requires a plan and a budget, and an accurate understanding of progress. If you don’t have these, you cannot make an objective assessment of progress – you can only make a subjective judgement which may well be wrong.

Tracking progress is based on the regular collection of information from the project team. A weekly collection is sufficient for most projects. The information should be collected formally through progress reports and informally from chats with project team members.

This information needs to be analysed at two levels:

- relative to the current point in time

- as a trend over time.

You should always expect deviations from the plan. Day-to-day variances in progress are less important than the trend. If the trend in progress is significantly different from the plan, the plan and your approach to the project should be reviewed.

It can also be helpful to track trends over time (also see page 170) in:

- volumes of issues and rate of resolutions

- risk levels

- rate of use of contingency.

A central way to communicate in a project is via progress reports. Good progress reporting helps in managing expectations. Poor progress reports will annoy stakeholders and indicate a badly run project.

- Identify audiences for progress reports. There may be several audiences, e.g. project team reporting to project manager, project manager reporting to sponsor and key stakeholders, project sponsor reporting to an organisation’s board.

- Check if there are any corporate standards for project reports. If there are, use them.

- Determine information needs. What do these different audiences need to know, and what would they like to know?

- Identify sources of information, normally project team members. Work out how often it is practical to collect the information.

- Define the format of reports: there may be several for different audiences. Make sure reports are specific enough to different audiences, e.g. if you have to produce a progress report for a director she probably wants different information in the report than a project team leader would. But keep the reports as similar as possible to minimise overhead.

- Develop processes to regularly collect the information. The information must be collected before the report is required and with sufficient time to turn it into a report. If there is a hierarchy of reports then the information needs to be available a few days before the top-level report is produced.

- Start collecting information and creating reports.

- Seek feedback and ensure the format is optimal – consider adapting to stakeholder needs, but try to avoid producing tailored versions of reports for individual managers.

- Ensure a culture develops where reports are produced on a timely basis and to a high standard.

- Periodically verify the data used to create reports. Unless you do this, there is a risk that you will be fed, deliberately or unintentionally, misleading information.

Usually, projects produce summary weekly reports, and more detailed reports on a less regular basis. A typical set of information in a report is:

- project name

- date and reporting period covered

- summary of progress and status

- main actions completed in last period

- main actions to be completed in next reporting period

- issues for escalation

- risks for escalation

- decisions and approvals required.

Running a project status review session

Project reports provide useful information, but for an accurate understanding of progress a review session is required, where direct dialogue occurs between the project manager and project team members. Reviews are an important part of managing a project.

Before holding a project review, you should determine:

- Why are you having a project review session? What information will you know and what questions will you be able to answer once this review session is complete? What outcomes or types of actions will happen following the meeting? If you cannot answer these questions – do not hold the review.

- Are you reviewing a sensible amount of information, and information that needs debate and discussion?

- Having a list of 100 questions you want to answer is not a practical meeting that can be completed in a sensible amount of time. Break it into several meetings.

- If they are simple yes/no questions or factual pieces of information, is it really necessary to have a meeting?

- Who is the review session for? There are differences between an internal review with a project manager and project team, one with the project sponsor, and one with project stakeholders, customers or executives.

The typical aim of a review session is to:

- Verify project reports and get a complete understanding of project status. This includes factual information such as work completed, but also intangible data such as the mood of the project team.

- Determine if remedial actions need to take place to maintain status.

- Identify opportunities to improve the project.

- Discuss plans moving forward and generally share information.

- Reduce the overhead on the project team in terms of reporting. Reporting is a key part of working on a project, but it is not the goal of projects to report. Whoever is running a review session has to balance between too-frequent reviews, creating too great an overhead, and too few, which means that insufficient information is gathered to provide control.

Typical contents of a review session are:

- Informing team of any changes in direction, baseline plans or other relevant information.

- Determining what the team did in the last period. Was it as planned; what was produced?

- Determining what the team plan to do in the next period. Does that match the project plan?

- Discussing upcoming milestones.

- Reviewing plans and making any amendments.

- Checking if there are any new issues, risks or changes the team want to raise.

- Assessing the progress on any issues, risks or changes the team are working on.

- Discussing any team or staff issues that may impact the project.

- Reporting back on actions held by the project manager or escalated for higher support.

- Any other points project team members want to discuss.

For more complex projects and programmes it is worth also reviewing dependencies between projects (see page 113) and any resource issues and conflicts (see page 191).

Following the review meeting you can make decisions about the project. Typical questions you should be able to answer are:

- Are you on track or not? What is the overall project status?

- If not, what will you do to bring the project back on track?

- What is your current view of the likely outcome of the project?

- Is there anything you need to escalate or warn the sponsor about?

- Are there any actions relating to team motivation or management?

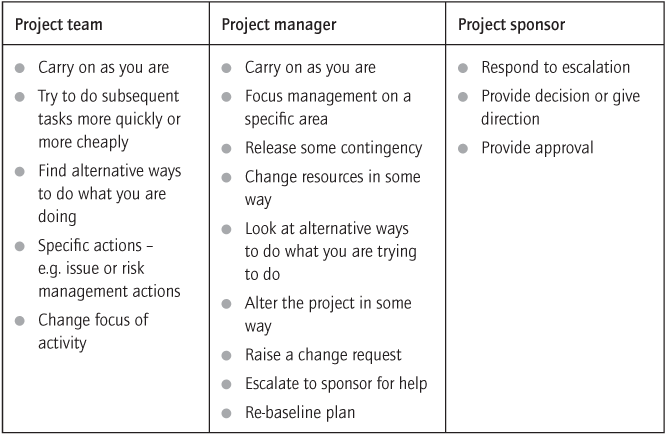

Typical actions that may be required following a review session are one or more of the following:

Managing dependencies

Dependencies between tasks are important parts of a project plan. Dependencies result in tasks in a plan being done in a certain order. There are two types of dependency:

- Internal dependencies – relationships between tasks within the project plan.

- External dependencies – relationships between tasks within the project and tasks external to a project. The latter may or may not be on another project. These are sometimes called interfaces.

It is important for the project manager to monitor and manage dependencies, or else projects can fail. Dependencies should be managed by the following steps:

- Identify dependencies. It is critical to identify all dependencies.

- What has to happen for a task to be completed?

- If dependencies are real they must be in the plan. Try to remove or break the dependency if possible, as dependencies constrain and increase timescales. If they can be removed they should be.

- Build the plan using the right type of dependency: start to finish, start to start, finish to finish, delay, etc. Wrong dependencies can elongate the plan unnecessarily.

- For external dependencies ensure you know:

- What project or piece of work is delivering the dependency? (Try to avoid making assumptions about delivery of dependencies; plan using verified facts.)

- Who is accountable for delivering the work you are dependent upon?

- Should the dependency be brought into the scope of the project?

- Monitor delivery of the dependency by getting periodic updates on progress, so that you can assess the degree of risk upon the project if it is not delivered on time.

- On critical dependencies, do not accept statements of progress; probe the progress reports as you would any part of your own project to be confident that they are accurate.

- Update plans in line with progress on delivery of dependencies.

Contingency plans

When a risk cannot be controlled, the alternative is to mitigate the impact it would have should it occur, with a contingency plan. A contingency plan is a series of actions that are only initiated should a risk event occur or when a defined trigger happens.

- Identify the risk events that you need a contingency plan for (see Chapter 10 for risk management advice).

- Define the contingency plan. Consult the team and use creativity. The creation of good contingency plans can be hard and needs real creativity.

- Determine what triggers your contingency plan. It is often assumed that the trigger for a contingency plan to be activated is the occurrence of a risk event. Unfortunately, because of the length of time it takes to implement, many contingency plans have to be activated before the risk occurs. Unless you understand when to implement the contingency plan, it is worthless.

- Ensure you have the resources to implement the contingency plan, or have a way of getting them should the contingency plan be implemented. Contingency plans are optional expenditure to reduce risk, and may be difficult to justify. Consider them as an investment in insurance.

- Ensure the contingency plan reduces risk. Some contingency plans sound great, but when analysed can be shown to result in no risk reduction, and so are not worthwhile.

- Ensure the sponsor and stakeholders understand the implications if the contingency plan is implemented. It may mean more cost, and often means a reduced scope.

- Monitor for the trigger event, and action the plan should the trigger occur.

- Maintain or update the contingency plan should the project change in a way that requires it to be updated.

When and how to escalate for help

Project managers cannot solve every problem they encounter. They often need to escalate for help. There is a balance with escalation: escalate as soon as you need to, but only when you need to. If you escalate every time you have problems you are not adding value as the project manager. But if you do not escalate when you should, you are not taking advantage of a valuable resource and may be increasing the risk.

- Understand the difference between escalation and keeping the sponsor informed.

- Warn people in advance that you may come to them for help. Most people are open to this if asked nicely. ‘Would it be OK if I come to you for help as the project progresses? I won’t do it too often, but if I’m stuck would it be OK to get your advice or support?’

- Decide, as issues arise, if you need to escalate. You should escalate if:

- you cannot resolve the issue yourself or with resources under your control/influence

- it will be significantly easier, quicker or cheaper to escalate than do it yourself

- it will help with project politics or expectations management if you escalate.

- Decide who you will escalate to: is it the sponsor, or another line manager? Most escalations will be to the sponsor. But the sponsor is not the only choice; there are many other members of staff who may be able to help you. Make use of your network to solve specific problems.

- Try to avoid making the request a surprise. If you are going to have to escalate try to link to points made in progress updates. ‘As I noted in last week’s report . . . so now I need help to …’

- Work out how you will phrase your request, and what your desired outcome is.

- Be clear about what you actually need. There are few things more irritating than a vague request for help. Follow the pattern: ‘We have an issue . . . The implications are . . . If you could . . . it would be resolved.’

- If possible, give options, and try to make the person you are asking feel as if they have a choice. When you hold a gun to someone’s head they will do what you ask, but they won’t like you for doing it!

- Choose the best time to ask for help. You can’t always choose the timing, but asking for help last thing on a Friday afternoon is less likely to get a positive response than asking at lunchtime on Monday.

- Request the specific help you need.

- Monitor results. If the help was effective, thank the sponsor. If not, you may have to do it again or escalate to an even more senior level.

Driving performance in a project team

No matter how brilliant a project manager is, unless the project team members do the work allocated to them the project will fail. A project manager has to be able to drive performance in the project team. A well-managed and motivated team will perform far better than a better resourced and skilled team that lacks motivation.

- Try to pick people who are motivated or interested in the project in the first place.

- Assign clear roles and responsibilities related to individuals’ capabilities and wants. Everyone in the team should know:

- why they are in the team

- what they are expected to deliver

- when they are expected to deliver it

- what resources they have at their disposal

- how much freedom they have to work out what they should be doing.

- Make sure you understand project progress and personal contribution towards it. The team will soon learn if you don’t, and progress will slacken.

- If there are problems don’t wait for things to get better. Respond to performance issues, both in project progress and levels of personal contribution to the project.

- Make use of the team. Listen to their comments and feedback. Use their advice or, if you are not going to, tell them why.

- Monitor team dynamics and team politics. Respond to team and interpersonal problems that are getting in the way of the team’s work.

- Even senior people are part of the team and have to come under the project manager’s control. Learn how to influence more senior people to do what you require.

- Use a reasonable proportion of time managing and motivating project team members. Keep the project team motivated by:

- Setting the project team’s expectations as to what it will be like to work on the project. If it will be chaotic and hard, tell them in advance.

- Explaining the importance of the project and receiving suitable feedback from senior managers.

- Ensuring the team has a clear idea about objectives and personal responsibilities.

- Keeping everyone updated on status.

- Feeding back on progress, so the team knows how the project is supported.

- Aligning performance management and annual appraisal process to performance on the project.

- Aligning project with personal needs, e.g. learning skills, being seen.

- Removing individual distractions, irritations and concerns – typical ones include:

- not feeling that they are adding value

- not knowing their personal work is valued

- not knowing that their career is progressing while on the project

- being unsure if they have a job role to go back to once the project is complete

- avoiding demotivation: factors such as uncertainty or lack of value will create demotivations.

- Don’t forget anyone in the team, especially geographically or physically separated staff. If they are working on the project, they are part of the team and need the same level of management.

- Thank or reward people for contributions appropriately.

Identifying and benefiting from quick wins

A quick win is an improvement that is visible, has benefit and is popular, that can be delivered quickly after the project starts. The quick win does not have to be profound or have a long-term impact on your organisation, but needs to be something that you can talk about and people will agree is a good thing. The best quick wins are easy and cheap to implement, and create positive discussion about the project.

- Make sure everyone in the project team understands the benefits and importance of quick wins to a project.

- Identify quick wins. There are many ways to identify quick wins, such as:

- brainstorming with your core team

- observing daily work in the organisation and listening to staff

- asking stakeholders

- being open to staff suggestions.

- Review the impact of each quick win. They must have a positive, even if intangible, value. If they have any negative impact or high cost they are almost certainly not worth pursuing.

- Determine which quick wins you will implement.

- Thank team members for every suggestion, and tell them if you are going to implement it or not. If you do not implement the idea try to tell people why. Doing this keeps people interested.

- Quick wins will form part of your plan of work, and once you have your work approved, implement them.

- Make sure every relevant team and individual is aware of the benefits you have quickly achieved. Quick wins will achieve little if they are not widely communicated.

- Cease communications after a period of time. Communicate loudly about your quick wins, but don’t communicate about them for ever. Quick wins are refreshing and beneficial, but can also start to sound stale after a while.

Managing third parties on projects

Not all tasks on projects will be completed by your own staff. Some activities may be completed by third parties. This can be a major component of project management and this checklist provides only very high-level guidance.

- Identify and scope the work required by the third party.

- Agree who will negotiate the supplier contract, and who will manage the supplier relationship in life (the procurement department or the project team?).

- Understand any organisation standards you have to comply with for this type of contract.

- Determine structure of contract required. Consider:

- Fixed price, time and materials, partnering and shared risk and reward, etc.

- Do you want the third party to provide some resources, produce deliverables, achieve an outcome or reduce risk? These have significant bearings on the type of contract and the price.

- Will the work be completely outsourced, or partially, or are they providing resources under your management control?

- Is the contract for this project alone or is it part of a larger contract? Does it just include help on the project or does it need to include maintenance, support or other services?

- How will project change and scope control be handled? This is critically important. A high percentage of contractual disputes are to do with handling changes to scope or requirements.

- How will disputes be resolved without the overhead of escalation?

- How will the payment schedule be linked to delivery and performance?

- What are your handover needs – consider training, documentation and in-life support.

- How much time do you have to put a contract in place? Are you in a hurry or do you have the time to optimise your choice?

- Determine your selection criteria. How are you going to determine the best supplier for you? Price is usually important, but in the longer run the quality of the supplier’s work is usually more important and provides greater value.

- Determine how you will judge the quality of the third party’s output or deliverables, and how you will accept or hand over deliverables. This should include any training or information the third party needs to provide you with.

- Choose a third party to do the work.

- Put a contract in place. The contract provides a structure to manage and a fallback if things go wrong. Day-to-day management should not continually refer to the contract.

- Explain to your own staff why you are working with a third party. Sometimes staff can be uncomfortable when third parties are used, or can feel under-valued. Be open so that future problems can be avoided.

- Define the way you will manage the third party, which will depend on:

- Whether day-to-day work by the third party is visible or invisible to you – i.e. is there a tangible output you can track, or do you depend on what they say?

- Whether you trust the third party, and have experience to base this trust upon.

- Whether you understand the third party's performance drivers and can align your needs with their performance success.

- Where the third party is based. Are they local or offshore?

- Who will act as the primary interface to this supplier?

- The degree of risk the third party is bearing on your behalf.

- Initiate work and actively manage with regular progress updates.

- Include the third party’s work in risk management. Consider what happens if they fail to deliver, are late or the price increases. How will you avoid this? How will you mitigate against this happening?

- Ensure complete handover. Once the supplier has completed and has been paid you may have limited opportunity for further support.

Dealing with problems – when and how to change project team members, and when to stop a project

Unfortunately, there are occasions when someone needs to be replaced on a project team.

- Before removing anyone, ascertain that they really are the cause of project problems or that the project will improve without them – do not assume this.

- Do not leave it too late. Your primary responsibility is to deliver the project, not to be nice to team members or avoid an uncomfortable situation.

- Make your decision based on the needs of the project, e.g. if the project needs intense effort, the team members need to be willing to work intensely; if they are not, then they are the wrong people for this project irrespective of other qualities.

- Check you have someone to replace the individual with. Some team members are so destructive that the team is better off without them even if there is no replacement, but on other occasions a poor performer is better than no one.

- Remember that judgements of suitability are not purely a function of personal performance, but also depend on the individual’s impact on the project team. A high-performer who disrupts the project team is as much a problem as a low-performer who does not.

Before removing anyone who has worked hard on a project you should check:

- Does the poorly performing individual understand what is required of them?

- Do they understand that they are performing poorly? Will some constructive feedback resolve the issue?

- Do you understand what is driving the poor performance? Can any of these reasons be easily resolved?

- Is the individual willing and able to overcome the performance issue?

After someone has been removed from a project it will impact on their performance assessments. It is important to differentiate between poor performance, changing needs and choice of wrong person. If changing project team members is not enough, the project may need to be stopped. A project should be stopped when:

- The project is unrecoverable and will not deliver. Don’t go on hoping for things to get better – if it has been bad for a long time, it is likely to continue to be so.

- The actual cost yet to be invested or spent is greater than the benefits.

- The opportunity cost of continuing is higher than the possible benefits.

- The situation in a business changes to such an extent that the project is irrelevant or the benefits the project will deliver decline below the remaining cost to deliver.

A project manager and sponsor should be brave and:

- Halt a failing project – identify if it can be realistically saved and, if not, abandon it.

- Don’t wait too long for it to improve – or keep hoping that improvement is just round the corner.

- Don’t overly penalise people for underperformance, unless the mistake is repeated. If the penalties are too high, people will avoid admitting mistakes and cover up problems for as long as they can.

- Even if the project is killed, try to learn from the experience and still review the project.

Signs to look out for in a failing project:

- Lack of understanding of real progress – i.e. progress is regularly worse than it should be according to reports and predictions.

- Increasing problems – such as increasing numbers of unresolved issues and increasing levels of risk.

- Increasing planning problems – work being squeezed into impossibly short periods, overly parallel working, testing and implementation cut back to unrealistically short timescales.

A strong project manager may resolve any of these issues, but they indicate major problems:

- Scope being reduced to hit targets, but to such an extent that the deliverables are no longer of value.

- No viable or believable action plan to bring the project back on track or to improve.

- Business needs change to such an extent that the project’s goals are not of value to the business any more.

Reducing a project’s duration

Project sponsors and project customers can place a wide variety of demands on project managers, but one of the most common is to be asked to reduce the duration of a project.

Ways to reduce a project’s duration include:

- More focused management, combined with encouragement or incentives for team members to work more effectively. Managing and motivating staff to tighter timescales can reduce a project’s duration.

- Faster decision making. Projects are subject to many management decisions and often have to wait for them. Faster decision making in a business may reduce project timescales.

- Adding resources can speed up the time to complete some project activities. Beware though – increased resource can speed up many projects, but it will not work in all cases and in some situations will actually slow a project down.

- Removing project constraints. Projects are subject to many constraints which can delay progress. Identify and remove them.

- Reducing the scope or quality of a project.

- Breaking a project into phases (see page 179).

- Time-boxing. Forcing completion or delivery within a set period of time creates focus in the project team on the core aspects of a project. It can be very successful, but usually has to be combined with reduced scope.

- Increasing the level of parallel working. The advantage of parallel working has to be balanced against higher risk. There are specialist approaches to parallel working such as concurrent or simultaneous engineering.

- Changing the project strategy. There are usually several ways to achieve an outcome. Review the plan or approach and look for alternative simpler or quicker ways. This can provide good results, especially if a project plan has never been reviewed.

- Stopping other projects that are getting in the way and using resources that would be more helpful on this project.