Stock markets

The world has changed dramatically in the last 30 years. The strong ideological opposition to capitalism has been replaced with stock markets in Moscow, Warsaw and Ho Chi Minh City. China, of all places, has two thriving stock exchanges, in Shanghai and Shenzhen, with over 3,000 companies listed. There are tens of millions of Chinese investors – more than in the UK – who can only be properly described as ‘capitalists’ given that they put at risk their savings on the expectations of a reward on their capital.

Over 140 countries now have stock markets. There must be something of great value offered by stock markets to pull so many societies towards them. Jiang Zemin, China’s former president, spoke with the fervour of a recent convert in declaring that robust stock markets are a vital component of a modern economy – they can bring great benefits to investors, companies and society, according to this enthusiast. Here we will concentrate on describing UK markets, but the principal features tend to be found in all stock exchanges.1

What is a stock market?

Stock markets are where government and industry can raise long-term capital and investors can buy and sell securities.2 Markets, whether they are for shares, bonds, cattle or fruit and vegetables, are simply mechanisms to allow the possibility of trade between individuals or organisations. Some markets (e.g. for sheep) are physical: there is a place at which the buyers and sellers meet. Other markets (e.g. for foreign currency) are merely a network, based on communication via telephone and computer, with no physical meeting place.

A few stock exchanges still have a place where buyers and sellers (or at least their representatives) meet to trade. For example, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) continues to make use of a large trading floor with thousands of face-to-face deals taking place every working day (open outcry trading). This is the traditional image of a stock market, and if television reporters have a story about what is going on in the world’s security markets, they often show an image of traders rushing around, talking quickly amid a flurry of small slips of paper on the NYSE trading floor.

Such a television reporter in London has more difficulty finding an image to represent security dealing. The London Stock Exchange (LSE), like many in the world today, has no trading floor. In the 1980s it decided to switch to a computer system to link buyers and sellers. This allows for a more efficient market than the old system and allows traders to be located anywhere. So long as they can link up to the LSE central computer, they can trade. Television journalists usually resort to reporting from one of the many dealing rooms owned by the financial groups. There they find rows of desks with hundreds of computer screens. The people in front of the screens may be brokers acting on behalf of investors buying or selling shares or bonds into the market. One of the screens on a desk will display the information on the LSE central computer, showing the latest trading prices, for example. Other screens may show information about companies, news, or provide analytical tools.

Even though these agents of the buyers and sellers of shares don’t physically meet their counterparts in other security house dealing rooms to complete a deal, there are times when good TV camera shots of frazzled and exhausted dealers can be obtained to show on the evening news – usually when the market has fallen a lot in one day.

Brokers and market makers

It is perfectly legal for investors to deal directly with each other off the exchange. (There are special forms that record the transfer of shares from one name to another – see Chapter 4.) However, the majority of share deals are conducted through brokers who act as agents for buyers and sellers. A broker will not contact another broker to complete the deal but will instead often go to a market maker. These middlemen stand ready to buy or sell shares on their own account. They quote two prices: the price at which they are willing to buy (lower price) and the price they offer shares for sale (called ‘making a book’). During the day they anticipate that they will make numerous deals buying shares and a roughly equal number selling shares in a company. The margin between the buying and selling prices delivers a profit to the market maker.

There are usually many market makers trading in a particular company’s shares. A high degree of competition between them ensures that the market makers’ spread between the bid (buying) and offer (selling) prices does not get too wide, putting investors at a disadvantage. (For more details on share trading, see Chapter 4.) Note that there are two alternative systems also operated by the LSE which do not require market makers, but market makers are nevertheless encouraged to participate.

Pricing – good old supply and demand

How are the prices of shares and other securities set? They are determined in much the same way as the prices for other goods and assets bought and sold in market places: by the forces of supply and demand.

Imagine a share is currently priced by market makers at 149p–150p. This means that the (say) four different market makers trading in this share stand ready to buy at 149p and sell at 150p. (It is unusual that all the market makers offer exactly the same prices, but please bear with the simplification for now.) Let us further assume that the current market price is in equilibrium – the forces of supply and demand are evenly balanced. The market makers will experience this equilibrium by a steady flow of buy and sell orders roughly matched in terms of volume. So we start with stability and the market makers feel no pressure to alter the price.

Now suppose that a negative item of news is released about the company. Investors become more pessimistic about the prospects for the firm’s future profits. Many of those who would have been buyers at 150p now decide not to pick up the telephone to ask their brokers to buy, thus demand falls. At the same time an increased number of sellers contact their brokers with instructions to sell. The price of 149p seems excellent to them given the poorer prospects.

The market makers stand in the middle receiving an unbalanced set of orders: there are now many more sell orders than buy orders. At 149p–150p the shares are no longer in equilibrium. Market makers need to balance their books, that is, they need to find a roughly equal number of buyers and sellers. In the situation described they are faced with a deluge of sell orders and a buyers’ strike. Something has to give. Most of the market makers are quick to change the prices they offer. In fact, many changed prices when they saw the news about the company on one of their computer screens. That is, they marked down the bid–offer spread. Some tried 148p–149p, but found that this was still not low enough to balance supply and demand. Certainly some investors were attracted to buy at 149p but nothing like enough to create equilibrium. At prices of 145p–146p the number of sell orders (at 145p) slows dramatically, while the number of buy orders (at 146p) increases. Finally, the market reaches a new equilibrium at 144p–145p. At least it does until the next piece of news or sentiment hits shares generally, or this company specifically.

What about those market makers who kept their price at 149p–150p? They found a massive number of investors offering to sell shares at 149p. The rule is that market makers are obliged to buy at the price they advertise on the LSE computer system (for deals up to a set maximum quantity of shares). They do not hold high levels of inventory in the shares in which they deal because they don’t have the enormous sums of money this would require (they deal in hundreds of different companies’ shares). They must quickly sell the shares they purchase. Unfortunately they find that the highest price available from other market makers has fallen to 144p. They lose 5p on every share they purchase. It is clear that all market makers have to respond to shifting market forces and cannot stand still.

The system described above is based on market makers to illustrate how supply and demand interact to alter prices. Since 1997 alongside the market maker system the London Stock Exchange has developed an ‘order-driven’ system of trading, in which it is possible for buyers and sellers to transact with each other (usually via brokers) leaving out the market makers. The same forces of supply and demand are at work. (The order-driven system is described in Chapter 4.)

A short history of the London Stock Exchange

Businesses need capital to begin and to grow. Capital simply means stored wealth and resources. Stock markets assist the flow of capital from savers to businesses seeking funds. They do this through two main types of capital markets: the equity markets for trading of company shares, and the bond markets for trading the debt of companies and governments.

Capital markets go back a long time. In the late Middle Ages in the Italian city states securities very much like modern shares were issued and traded, as were government bonds. The demand from investors in British companies to be able to buy and sell shares led to the creation of a market in London. At first this was very informal; holders of financial securities (e.g. shares) would meet at known places, especially coffee-houses in the ancient part of London: the City (the ‘Square Mile’ that the Romans built a wall around, just to the north-west of the Tower of London). Early in the nineteenth century the Stock Exchange developed a set of rules and procedures designed to enable investors to buy and sell shares with ease and to minimise the risk of fraud or unfairness.

The rapid economic expansion of the nineteenth century fuelled the demand for share issuance and the trading of shares between investors. Eventually there were 20 stock exchanges in cities up and down the UK. These have now been amalgamated with London.

‘Big Bang’

Because of the LSE’s origin it tended to be a very clubby place. Members of the club (brokers, etc) ran things with a bias toward their own interests. There was little competition and commission rates were kept high. It became clear in the 1970s and 1980s that the LSE was losing trade to overseas stock markets. The large financial institutions, such as pension funds and insurance companies, were naturally in favour of a shift from fixed commission rates being paid to brokers to negotiated commissions. Further pressure was applied by the competition watchdogs to break up the cosy cartel.

The gentlemanly way of doing business ended in 1986 with the ‘Big Bang’. This is the term used for a collection of reforms implemented at the same time: fixed broker commissions disappeared; foreign competitors were allowed to own member firms (market makers or brokers); and the screen-based computer system of trading replaced floor-based trading.

The market makers and brokers quickly passed into the hands of large financial conglomerates. Commission fell sharply for large orders (from 0.4 per cent to around 0.2 per cent of the value traded). However, private clients (investors buying small quantities of shares on their own account) saw an initial slight rise in commission because it had previously been subsidised by the fees charged to the institutions. Brokers started to specialise. Some would offer the traditional service of advice and dealing, whereas others would offer a no-frills dealing-only service. (This execution-only service is now very cheap – see Chapter 4.)

The new financial conglomerates, offering a wide range of services, such as retail banking, market making, broking, investment management and insurance, were now able to compete with the big players in New York, Tokyo, Frankfurt and Geneva. To prevent conflicts of interest within the financial service firms damaging the position of clients, ‘Chinese walls’ were established. These were designed as barriers to prevent sensitive information being passed on to another branch of the organisation. For example, if an investor holding 10 per cent of the shares of a company asks the broker department to sell their shares, they do not want, say, the fund (asset) management department to hear about it before they have off-loaded the shares at a good price – the fund managers may sell first, depressing the price. Likewise, the corporate finance department assisting a company trying to acquire a competitor should be prevented from passing on this information to other members of the financial conglomerate, as they may be tempted to buy shares in the target company prior to the bid, in the expectation of making a large return on the announcement (a form of insider dealing).

Chinese walls have worked reasonably well, but they are not as strong as the public relations department of these financial organisations would have you believe.

Recent moves

After centuries of being an organisation owned and run by its members, in 2001 the LSE became a public limited company with its shares traded on a secondary market – the shares are quoted on its own Main Market (Official List) and anyone is now free to purchase these shares. It has come a long way from its clubby days. It remains one of the biggest stock markets in the world. See Table 3.1 and note the position of China’s and India’s exchanges having leap-frogged most western markets recently.

Table 3.1 Capitalisation (market value of shares) of non-foreign companies

| Exchange | US$ billion, beginning of 2019 |

| New York Stock Exchange | 20,679 |

| NASDAQ (US) | 9,757 |

| Japan Exchange Group | 5,297 |

| Shanghai SE | 3,919 |

| Euronext (Paris, Amsterdam, Brussels, Lisbon, Dublin) | 3,840 |

| Hong Kong Exchanges | 3,819 |

| London Stock Exchange Group | 3,638 |

| Shenzhen SE | 2,405 |

| National Stock Exchange of India | 2,056 |

| TMX Group (Canada) | 1,937 |

| Deutsche Börse | 1,755 |

Source: World Federation of Exchange’s Annual Statistics Guide, 2018: www.world-exchanges.org/our-work/articles/wfe-annual-statistics-guide-volume-4

In 2004 the London Stock Exchange moved from its historic site in Old Broad Street to Paternoster Square near St Paul’s Cathedral. The exchange toyed with the idea of moving out of the City but decided that its identity is tied too closely to the Square Mile to move outside.

The international scene

More change is in the air. Stock exchanges in Europe have been busy merging. The French, Dutch, Belgian and Portuguese bourses merged around the turn of the millennium to form Euronext which, in turn, bought the Irish stock exchange in 2018, and the Norwegian Oslo Bors in 2019. Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), a group of energy, metals and other commodities exchanges, owns the NYSE. The London Stock Exchange has merged with its Italian counterpart and NASDAQ, the US giant, has merged with OMX Nordic (comprising Baltic and Scandinavian exchanges) to form NASDAQ Nordic and NASDAQ Baltic as well as its original US exchange. The Deutsche Börse, which tried to get hitched to other exchanges several times, is still something of a loner.

The European Union has encouraged greater competition for share trades through MiFID legislation. This is the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive. Brokers must now demonstrate that they are achieving the keenest price and using the most efficient, cost-effective trading venues3. New exchanges (cross-border outfits such as Cboe Europe Equities and Aquis Exchange) sprang up to compete with the traditional exchanges. These have taken a significant share of trading in large companies’ shares.

Variety of securities traded

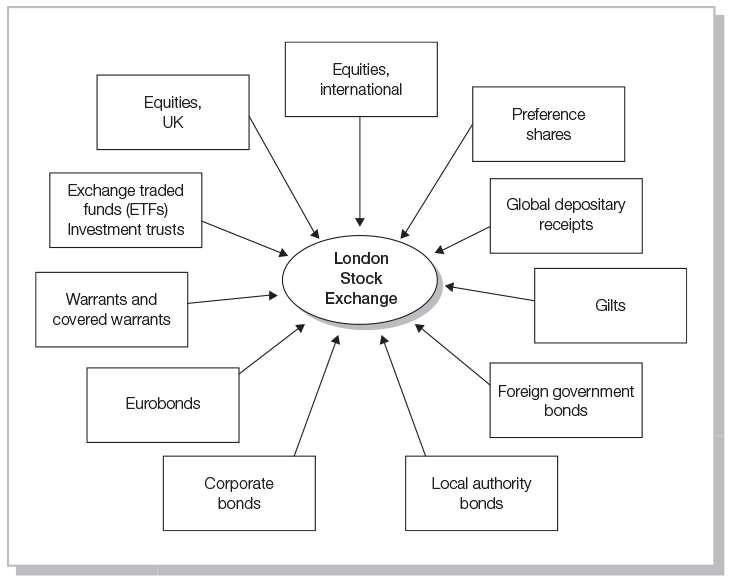

The LSE creates a market place for many other types of financial securities besides shares.

Many types of fixed-interest securities are traded in London, including gilts, local authority bonds, foreign government bonds, sterling corporate bonds and Eurobonds. The UK government bond (or gilt) market (lending to the UK government) is big. In the year ended April 2019, for example, £99 billion of gilts were sold to add to the £1,930 billion already in issue. In addition, foreign governments sold bonds through the LSE. Sterling bonds issued by companies (corporate bonds where the interest and the final redemption payment are in pounds sterling) comprise a much smaller market than government bonds. In a typical year over £200 billion is raised through the selling of Eurobonds traded on the London Stock Exchange (bonds are described in Chapter 6).

Figure 3.1 The main types of financial securities sold on the London Stock Exchange

Specialist securities, such as warrants and covered warrants, are normally bought and traded by a few investors who are particularly knowledgeable in investment matters (warrants are a type of derivative security and are discussed in Chapter 10).

In addition to trading shares of overseas companies (international equities), there is a market in depositary receipts (DRs). These are certificates that can be bought and sold, and represent evidence of ownership of a company’s shares held by a depository. Thus, an Indian company’s shares could be packaged in, say, groups of five by a depository (usually a bank) which then sells a certificate representing a bundle of shares. The depositary receipt can be denominated in a currency other than the corporation’s domestic currency and dividends can be received in the currency of the depositary receipt (say, pounds) rather than the currency of the original shares (say, rupees). These are attractive securities for sophisticated international investors because they may be more liquid and more easily traded than the underlying shares.

Exchange traded funds (ETFs) and exchange traded commodities (ETCs) are low-cost companies that invest money raised (by selling shares) into a range of shares or other securities to track a particular stock market index (e.g. the FTSE 100 index) or other sectors (e.g. commodity prices). See Chapter 5.

LSE’s primary market

Through its control of the primary market in listed securities, the LSE has succeeded in encouraging large sums of money to flow annually to firms wanting to invest and grow (see Table 3.2). In 2019 there were over 900 UK companies and over 220 non-UK companies on the Main Market (Official List). The vast majority of these companies raised funds by selling shares, bonds or other financial instruments through the LSE either when they first floated or in subsequent years (e.g. through a rights issue). Over 900 companies (769 UK and 135 international) are on the Exchange’s market for smaller and younger companies, the Alternative Investment Market (AIM). These companies, too, have raised precious funds to allow growth.

In 2017 alone, firms on the LSE raised new capital amounting to £280 billion by selling equity and fixed interest securities. This is the equivalent of £4,121 per man, woman and child in the UK. Of course, in the same year companies would also have been transferring money the other way by, for example, redeeming bonds, paying interest on debt or dividends on shares. Nevertheless, it is clear that large sums are raised for companies through the primary market.

Each year there is great interest and excitement inside dozens of companies as they prepare for flotation. The year 2018 was a watershed year for 67 UK and 15 foreign companies that joined the Main Market, and 52 UK and 13 foreign companies that joined the AIM.

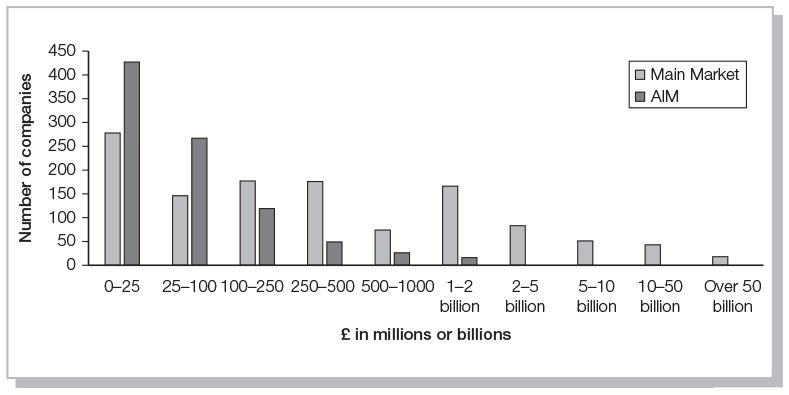

Given the high costs associated with gaining a place on the Main Market or AIM in the first place (£500,000 or more for MM), it may be a surprise to find that the market capitalisation (share price × number of shares in issue) of the majority of quoted companies is less than £100 million (see Figure 3.2).

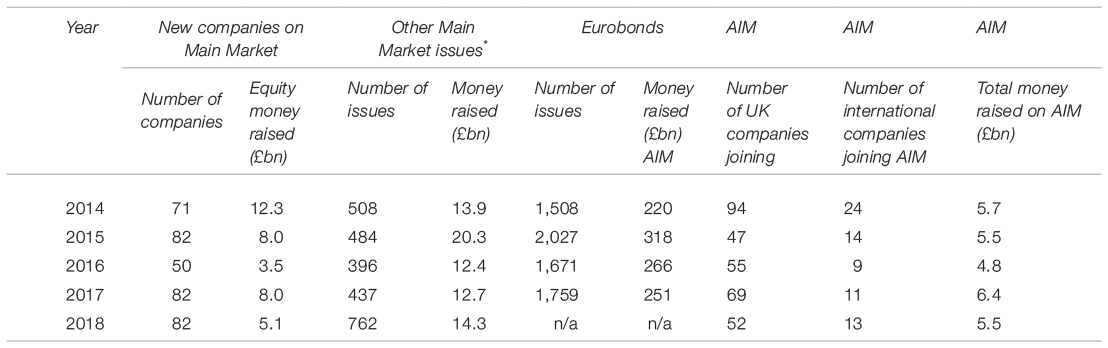

Table 3.2 Money raised by selling shares and eurobonds on the Main Market and the Alternative Investment Market, 2014–18 (in £m)

*’Other issues’ are for companies that have been on the Stock Exchange for many y ears raising more equity funds through, say, a rights issue

Source: Data sourced from London Stock Exchange; factsheets and Main Market and AIM st atistics files are located in the statistics section of its website

LSE’s secondary market

The amount of shareholder-to-shareholder trade is very large. On a typical day over 1 million bargains (trades between buyers and sellers) are struck between investors in shares on the LSE, worth over £5 billion. The size of bargains varies enormously, from £500 trades by private investors to hundreds of millions by the major funds, but the average is around £6,000.

The secondary market turnover exceeds the primary market sales. Indeed, the amount raised in the primary equity market in a year is about the same as the value of shares that trade hands in a few days in the secondary market. This high level of activity ensures a liquid market enabling shares to change ownership speedily, at low cost and without large movements in price – one of the main objectives of a well-run exchange. You are able to buy or sell shares during the trading hours, which are between 08.00 and 16.30 Monday to Friday.

The Main Market (The Official List)

Companies wishing to be listed have to sign a listing agreement that commits directors to certain standards of behaviour and levels of reporting to shareholders. To ‘go public’ and become a listed company is a major step for a firm, and the substantial sums of money involved can lead to a new, accelerated phase of business growth. Obtaining a quotation as a listed company is not a step to be taken lightly as the legal implications are enormous. The United Kingdom Listing Authority (UKLA), part of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), rigorously enforces a set of demanding rules, and the directors will be put under the strain of new and greater responsibilities both at the time of flotation and in subsequent years.

Joining the Main Market of the LSE involves two stages. The securities (usually shares) have to be (a) admitted to the Official List by the UKLA and also, (b) admitted by the Exchange for trading.

Many firms consider the stresses and the costs worth it because listing brings numerous advantages. For example, there are large benefits to shareholders. The LSE’s Main Market is one of the world’s most dynamic, transparent and liquid markets for trading shares and other securities. Shareholders benefit from the availability of a speedy, cheap secondary market if they wish to sell. Not only do shareholders like to know that they can sell shares when they want to, they may simply want to know the market value of their holdings even if they have no intention of selling at present. By contrast, an unquoted firm’s shareholders often find it very difficult to assess the market value of their holding.

Also, the floated companies gain access to a large pool of investment capital allowing firms to grow. Because investors in financial securities with a stock market quotation are assured that they are generally able to sell their shares quickly, cheaply and with a reasonable degree of certainty about the price, they are willing to pay a higher price than they would if selling was slow, or expensive, or the sale price was subject to much uncertainty caused by illiquidity.

The status and visibility of a company can be enhanced by being included on the prestigious Official List. Banks and other financial institutions generally have more confidence in a quoted firm and therefore are more likely to provide funds at lower cost. Their confidence is raised because the company’s activities are now subject to detailed scrutiny. Furthermore, the publicity surrounding the process of gaining a quotation may have a positive impact on the image of the firm in the eyes of customers, suppliers and employees, and so may lead to a beneficial effect on day-to-day business.

In order to create a stable market and encourage investors to place their money with companies, the UKLA tries to reduce the risk of investing by ensuring that the firms obtaining a quotation abide by high standards and conform to strict rules. For example, the directors are required to prepare a detailed prospectus (‘listing particulars’) to inform potential investors about the company. (More on this in Chapter 16.)

Companies obtaining a listing must ensure that at least 25 per cent of their share capital is in public hands, to ensure that the shares are capable of being traded actively on the market.4 ‘Public’ means people or organisations not associated with the directors or major shareholders. If a reasonably active secondary market is not established, trading may become stultified and the shares may become illiquid. Also, many crucial shareholder votes require a 75 per cent majority and so allowing dominant owners more than 75 per cent puts too much power in their hands.

The UKLA tries to ensure that the ‘quality’ of the company is sufficiently high to appeal to the investment community. The management team must have the necessary range and depth, and there must be a high degree of continuity and stability of management over recent years. Investors do not like to be over-reliant on the talents of one individual and so will expect a team of able directors, including some non-executives, and an appropriately qualified finance director.

The UKLA usually insists that a company has a track record (in the form of accounting figures) stretching back at least three years. This applies to companies that have a premium listing, the vast majority of listed companies. Recently, a standard listing regime has been introduced which does not require three years of figures and is far less tough on a number of other quality indicators and ongoing restraints, such as requiring shareholder approval for significant transactions. Given that few firms have gone for standard listing we will concentrate on premium listing.5 It would seem that companies recognise the advantages of being under a regime of tight rules because of the extra reassurance for shareholders, and so are generally sticking with premium listings.

The company floating on the Main Market via a premium listing hires a sponsor (issuing house) to advise on the process and provide reassurance to the UKLA and the investment community about the quality of the company and compliance with the listing rules. The sponsor (approved by the UKLA) may be a bank, stockbroker or other professional adviser. Even though the sponsor’s fee is paid by the company floating, the sponsor is an organisation with a high reputation to preserve and will not hesitate to drop a bad company or suggest changes to a mediocre one. Clearly, Aston Martin made the grade.

Article 3.1 - Aston Martin cuts maximum share price for IPO

By Peter Campbell

The carmaker on Monday reduced the top of its price range from £22.50 a share to £20. It also lifted the bottom end of the range from £17.50 to £18.50. All of the books are covered within the new range. The new range gives the group an expected valuation of between £4.2bn and £4.5bn.

Aston’s entry on to the London stock market — the shares are due to begin trading on Wednesday — marks the revival of the James Bond car manufacturer, which despite its illustrious brand has been bankrupt seven times in its century-long history. In the first half of the year it reported pre-tax profits of £20.8m, with revenues of £449.9m. Operating profits rose 14 per cent to £106m. The carmaker has sought to liken itself to Ferrari, seeking a valuation suitable for luxury goods companies rather than traditional car manufacturers.

Andy Palmer, Aston’s chief executive, joined the group from Nissan in 2014 with the aim of turning round the business. Under his tenure the company has crafted a strategy to release a new car every year, push into new segments with its SUV and mid-engine models, and revive the Lagonda brand as a fully electric rival to Rolls-Royce or Bentley.

Ahead of its listing Aston has begun building an independent board, appointing Penny Hughes, a former RBS board member who has significant branding experience from her tenure at Coca-Cola, as chair.

About 25 per cent of Aston’s shares will be sold by its existing owners, Italian fund Investindustrial and a number of Kuwaiti shareholders.

Daimler, the Mercedes-Benz owner that has a technology-sharing agreement with Aston and supplies it with V8 engines and electronics, will maintain its 4.9 per cent stake.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 1 October 2018

© The Financial Times Limited 2018. All Rights Reserved.

Company directors have to jump through hoops to obtain a listing in the first place. But even after flotation they are unable to relax. The UKLA insists on ‘continuing obligations’ designed to protect or enlighten shareholders. All price-sensitive information has to be given to the market as soon as possible and there must be ‘full and accurate disclosure’. Information is price-sensitive if it might influence the share price or the trading in the shares. Investors need to be sure that they are not disadvantaged by market distortions caused by some participants having the benefit of superior information. Public announcements will be required in a number of instances, for example for the development of major new products, the signing of significant contracts, details of acquisitions, a sale of large assets, a change in directors or a decision to pay a dividend. The Wasps rugby club got into trouble for not accurately informing the market.

Article 3.2 - Wasps rugby club faces FCA probe over market statements

By Caroline Binham

Rugby club Wasps is being investigated by the UK’s financial regulator over whether it misled the market about the state of its finances and how quickly it rectified the matter. The Financial Conduct Authority’s scrutiny comes after the 152-year old Premiership club admitted to creditors in late 2017 that it had overstated its earnings.

A £1.1m capital injection by Derek Richardson, the Irish businessman who owns Wasps and is its chairman, was wrongly stated as income. According to a market announcement made in December 2017, this cut the club’s earnings to £2.4m rather than the £3.5m it first stated.

The watchdog has opened a formal investigation and is summoning individuals for interviews, said people familiar with the situation. The FCA has the power to fine and criminally prosecute breaches of its market-cleanliness rules.

Wasps is the latest entity beyond the financial sector to find itself in the crosshairs of the FCA over its market statements. The regulator, which acts as the UK Listing Authority, opened investigations into publicly traded companies including Carillion, Cobham, Telit and Interserve over the accuracy and timeliness of their public announcements. It also levied a record £27.4m fine on Rio Tinto for breaches, and made Tesco set up a groundbreaking compensation scheme after accounting misstatements.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 12 April 2019.

© The Financial Times Limited 2019. All Rights Reserved.

There are strict rules concerning the buying and selling of the company’s shares by its own directors once it is on the stock exchange. Directors are prevented from dealing for a minimum period (normally two months) prior to an announcement of regularly recurring information such as annual results. They are also forbidden to deal before the announcement of matters of an exceptional nature involving unpublished information that is potentially price-sensitive. These rules apply to any employee in possession of such information. All dealings in the company’s shares by directors have to be reported to the market

Most financial websites (www.advfn.com, www.Londonstockexchange.com) show all major announcements made by companies going back many years, including director purchases and sales.

The Alternative Investment Market

There is a long-recognised need for small, young companies to be able to raise equity capital. However, many of these are excluded from the Main Market because of the cost of obtaining and maintaining a listing. London, like many developed stock exchanges, has an alternative equity market that sets less stringent rules and regulations for joining or remaining quoted (often called second-tier markets).

Lightly regulated or unregulated markets have a continuing dilemma. If the regulation is too lax, scandals of fraud or incompetence will arise, damaging the image and credibility of the market, and thus reducing the flow of investor funds to companies. The German small companies market, Neuer Markt, was forced to close down in 2002 because of the loss of confidence among investors: there were some blatant frauds as well as over-hyped expectations, and share prices fell an average of 95 per cent. On the other hand, if the market is too tightly regulated, with more company investigations, more information disclosure and a requirement for longer trading track records prior to flotation, the associated costs and inconvenience will deter many companies from seeking a quotation.

The driving philosophy behind the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) is to offer young and developing companies access to new sources of finance, while providing investors with the opportunity to buy and sell shares in a trading environment that is run, regulated and marketed by the LSE. Efforts were made to keep the costs down and make the rules as simple as possible. In contrast to the Main Market, there is no requirement for AIM companies to have been in business for a minimum three-year period or for a set proportion of their shares to be in public hands – if they wish to sell only 1 per cent or 5 per cent of the shares to outsiders then that is OK.

However, investors have some degree of reassurance about the quality of companies coming to the market. These firms have to appoint, and retain at all times, a nominated adviser and nominated broker. The nominated adviser (‘nomad’) is selected by the corporation from a Stock Exchange-approved register. These advisers have demonstrated to the Exchange that they have sufficient experience and qualifications to act as a ‘quality controller’, confirming to the LSE that the company has complied with the rules. Unlike Main Market companies there is no pre-vetting of admission documents by the UKLA or the Exchange, as a lot of weight is placed on the nomad’s investigations and informed opinion about the company.

Nominated brokers have an important role to play in bringing buyers and sellers of shares together. Investors in the company are reassured that at least one broker is ready to help shareholders to trade. They also represent the company to investors (a kind of PR role). The adviser and broker are to be retained throughout the company’s life on the AIM. They have high reputations and it is regarded as a very bad sign if either of them abruptly refuses further association with a firm.

AIM companies are also expected to comply with strict rules regarding the publication of price-sensitive information and the quality of annual and interim reports (there is more on accounts in Chapter 11). Upon flotation, an AIM admission document is required. This is similar to a prospectus required for companies floating on the Main Market, but is less detailed and therefore cheaper. But even this goes so far as to state the directors’ unspent convictions and all bankruptcies of companies where they were directors. The LSE charges companies a few thousand pounds per year to maintain a quotation on the AIM. If to this amount is added the cost of financial advisers and management time spent communicating with institutions and investors, the annual cost of being quoted on the AIM runs into tens of thousands of pounds. This can be too expensive for many companies. AIM companies are not bound by the Listing Rules administered by the UKLA but instead are subject to the AIM rules, written and administered by the LSE.

The article below shows a company, Servelec, that chose the Main Market because it wants ‘bigger cheques from institutional investors’ to help buy other technology companies. The next article, on the other hand, shows a much larger company, Asos, content with being on the AIM.

Article 3.3 - Servelec IPO lifts Sheffield tech profile

By Sally Davies

Performing as strippers was the job of last resort for Sheffield’s former metalworkers in the hit British film The Full Monty. Today, they might find more luck as programmers.

Servelec, a software and services company with roots in the city’s once-proud steel mills, is set to float 68.3m shares on London’s main stock exchange today with an expected valuation of £122m.

Servelec had revenues of £39.4m last year, with a profit before tax of £10.9m. “Investors’ appetite for risk has increased – we see what’s going on on the other side of the pond and the successes there,” says Adam Lawson, analyst at Panmure Gordon, referring to the big valuations for tech companies listing in the US.

Servelec’s automation arm provides software and control systems to major UK utilities, broadcasters, lighthouses and North Sea oil rigs.

Servelec, which was advised by Investec, joined the main market rather than the more flexible Aim in order to attract bigger cheques from institutional investors, says Mr Stubbs [Chief Executive].

The company comes to the London market with no debt and £5m in cash – which Mr Stubbs indicates will be used for acquisitions. “What Servelec is good at is improving efficiency,” says Mr Stubbs. “We want to buy smaller companies with good technology that are looking to become part of a larger company to accelerate their growth.”

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 1 December 2013.

© The Financial Times Limited 2013. All Rights Reserved.

Article 3.4 - Asos warns full year sales growth will be at ‘lower end of range’

By Jonathan Eley

Asos, the Aim-listed online fashion retailer whose market value now exceeds that of Marks and Spencer, said full year sales growth would be “towards the lower end” of a 25–30 per cent range. In the four months to end-June, retail sales overall were up 22 per cent with UK sales — still over a third of the total — growing slightly ahead of that. Pre-tax profit is likely to be in line with consensus, which is around £100m on £2.45bn of revenue.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 12 July 2018

© The Financial Times Limited 2018. All Rights Reserved.

NEX exchange

Companies that do not want to pay the costs of a flotation on one of the markets run by the LSE (this can range from £100,000 to £1 million just for getting on the market in the first place) and the ongoing annual costs, could go for a quotation on the London-based NEX Exchange. By having their shares quoted on NEX Exchange, companies provide a service to their shareholders, allowing them to buy and sell shares. It also allows the company to gain access to capital, for example, by selling more shares in a rights issue, without submitting to the rigour and expense of a quotation on LSE. The downside for investors is that trading in NEX Exchange shares can be illiquid (not many buyers and sellers), with high dealing costs. Buy and sell prices offered are frequently 20% or more apart, despite there often being a number of competing market makers making a market in a company’s shares.

Companies must have at least 12 months of audited accounts to be admitted. Joining fees range from £8,000 to £50,000. There is an annual fee of £6,800. When companies join the market there are ‘corporate adviser’s’ fees of around £20,000. If new capital is raised fees can climb above £100,000. Companies also pay an annual retainer fee to their Corporate Advisers. Companies are required to have one-tenth of their shares in public hands, in a ‘free float’.

NEX Exchange companies are generally very small and often brand new, but there are also some long-established and well-known firms, such as Adnams, the brewers. Note that the criteria for companies gaining admission for a quote on NEX Exchange do not include compliance with the normal listing rules, so investors have far fewer quality assurances about these companies. However, these companies have to adhere to its code of conduct, so, for example, insider trading by directors is prohibited, they must have a corporate adviser (e.g. an investment bank, corporate broker, accountant or lawyer) at all times, an ‘admission document’ must be produced, and the market must be properly informed of any developments or any information that may have an impact on the financial status of the company.

The corporate adviser will advise on compliance with NEX Exchange rules and insist that good accounting systems are in place with annual audited accounts and semi-annual accounts. They also ensure that the company has at least one non-executive director, and adequate working capital.

There are 89 companies currently paying for NEX Exchange’s quote dealing facility. In addition, NEX Exchange provides an alternative trading facility for 500 AIM companies. NEX Exchange is often seen as a nursery market for companies that eventually grow big enough for AIM or the Main Market. Despite this many companies are happy to remain on NEX Exchange for several years and have no desire to increase their costs by moving up to the LSE markets.

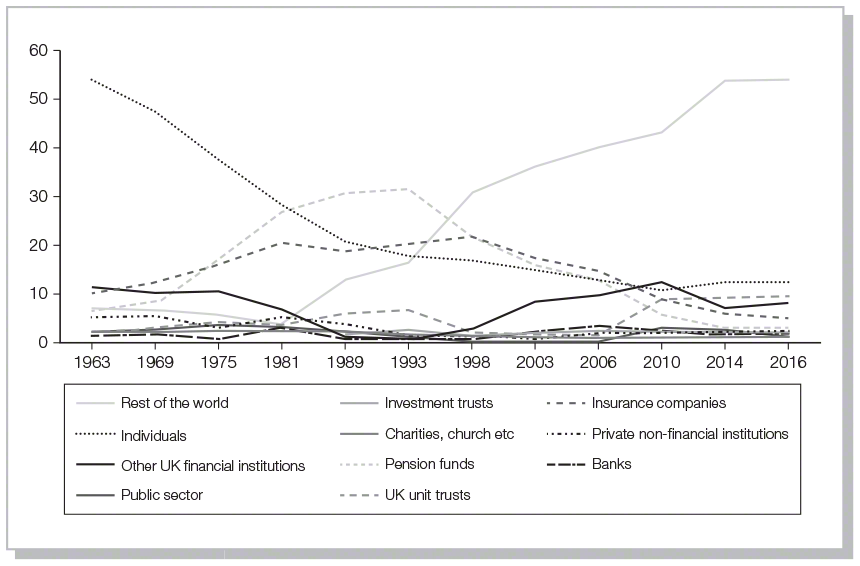

Who owns UK shares?

There has been a transformation in the pattern of share ownership in Britain over the last six decades (see Figure 3.3). Individual investors used to dominate the market, holding 54% of UK quoted company shares in 1963. This sector showed a continuous gradual decline, falling to an official 10% in 2012, but picking up to reach 12.5% more recently. Note however that most private investors now hold their shares via broker’s nominee accounts (see Chapter 4) and so they do not appear as the owner. If this artifice is removed, individual holdings amount to at least double the official level.

Figure 3.3 Ownership of UK-quoted shares, distribution by sector (%)

The reason for the long-term decline was not just that individual investors became less interested in the stock market – an attitude not helped by the stock market downturns of 2000–02 and 2007–09 – but also the tendency to switch from direct investment to collective investment vehicles, such as unit trusts, or via insurance products or pension funds, where they gain benefits of diversification and skilled management. Unit trusts have been the big winners, growing in importance from 2% of UK shares in the 1980s to 9.5% today. Although the mode of investment has moved somewhat from direct to indirect, Britain remains a society with a deep interest in the stock market. Very few people are immune from the performance of the LSE. The vast majority of the UK population have a pension plan or endowment savings scheme, or a unit trust investment, which invests in the equity market.

A major reason for the decline in the proportion held by UK individuals is the internationalisation of financial markets. UK investors have diversified by buying more overseas shares, which they can now do very easily. More importantly for the ownership statistics of UK shares has been the remarkable growth in the proportion held by investors from outside the UK: only 7% in 1963, but 53.9% in 2016. This increase partly reflects international mergers where the new company is listed in the UK. Take BHP Billiton for example: its origins are largely in Australia and so it has many investors there, and also attracts holders from a hundred other nations. Other foreign companies have floated their UK subsidiaries but retain a large shareholding.

The main factor influencing the rise in foreign ownership is the global phenomenon of the increased willingness to buy shares in overseas markets. It has become much easier for non-native individual and institutional investors to buy shares abroad, particularly in the UK, with its open equity markets, helped by electronic trading allowing long-distance buying. Reinforcing that, we have lived through a remarkable time when the world, particularly the ‘developing world’, became wealthy at an amazingly fast rate. There are now hundreds of millions of investors in Asia for example, looking to save through share investing. Indeed, around 8% of UK shares are owned by Asians or their institutions.

The greatest source of foreign investment comes from North American investors, who account for half of overseas buyers. That is, roughly 26% of the value of all UK shares are owned by North American institutions or individual investors. Large sovereign wealth funds are investing, say oil money, in shares around the world. Qatar, for example, holds one-fifth of British Airways-owner International Airlines Group.

UK insurance and pension funds used to dominate UK company share registers, with a combined 52% of listed UK shares in 1992. The tax-favoured status of pension funds make them a very attractive vehicle for savings, resulting in billions of pounds being put into them each year. However, in the last three decades they have been taking money out of UK-quoted shares and placing it in other investments such as bonds, overseas shares and venture capital.

The role of stock exchanges

Traditionally, exchanges perform the following tasks to play their valuable role in a modern society:

- Supervision of trading to ensure fairness and efficiency.

- The authorisation and regulation of market participants such as brokers and market makers.

- Creation of an environment in which prices are formed efficiently and without distortion (price discovery or price formation). This requires not only regulation of a high order and low transaction costs but also a liquid market in which there are many buyers and sellers, permitting investors to enter or exit quickly without moving the price.

- Organisation of the clearing and settlement of transactions – after the deal has been struck the buyer must pay for the shares and the shares must be transferred to the new owners.(See Chapter 4).

- The regulation of the admission of companies to the exchange and the regulation of companies on the exchange.

- The dissemination of information (trading data, prices and company announcements). Investors are more willing to trade if prompt and complete information about trades and prices is available.

In recent years there has been a questioning of the need for stock exchanges to carry out all these activities. In the case of the LSE, the settlement of transactions was long ago handed over to an organisation called CREST (discussed in Chapter 4). The responsibility for authorising the listing of companies has been transferred to the UKLA arm of the Financial Conduct Authority. The LSE’s Regulatory News Service, which distributes important company announcements and other price-sensitive financial news, now has to compete with other distribution platforms outside the LSE’s control as listed companies are now able to choose between providers for news dissemination platforms. Despite all this upheaval, the LSE still retains an important role in the supervision of trading and the distribution of trading and pricing information.

Useful websites

| www.aquis.eu | Aquis Exchange |

| www.advfn.com | ADVFN |

| www.markets.cboe.com/europe/ equities | Cboe Europe Equities |

| www.euroclear.com | Euroclear/CREST |

| www.deutsche-boerse.com | Deutsche Börse |

| www.euronext.com/en | Euronext |

| www.fese.eu | Federation of European Securities Exchanges |

| www.fca.org.uk | The Financial Conduct Authority |

| www.ft.com | The Financial Times |

| www.ftserusssell.com | FTSE Russell |

| www.ii.co.uk | Interactive Investor |

| www.londonstockexchange.com | London Stock Exchange |

| www.nasdaq.com | NASDAQ |

| www.nexexchange.com | Nex Exchange |

| www.nyse.com | New York Stock Exchange |

| www.ons.gov.uk | Office for National Statistics |

| www.fca.org.uk/markets/ukla | The United Kingdom Listing Authority |

| www.world-exchanges.org | World Federation of Exchanges |

_______________

1 Stock exchange and stock market will be used interchangeably. Bourse is an alternative word used particularly in Continental Europe.

2 These are the principal and historical functions of stock markets. However, major markets, such as the London Stock Exchange, now also trade a variety of securities, some of which are short term.

3 ‘Best execution’, a requirement of MiFID, of a trade means demonstrating that the broker obtained the best price, low cost of execution, speed and the likelihood of settlement of the trade going well.

4 If there is plenty of liquidity the UKLA may, at its discretion, reduce the minimum free float – usually to around 20 per cent.

5 In 2013 the LSE went even further and introduced ‘Admission via the High Growth Segment’. This requires only 10 per cent of the shares in a free float (minimum £30 million). It is even more lightly regulated. Again, few, if any, companies are queuing at the door for this.