Buying and selling shares

There is absolutely no reason to be in awe of stockbrokers, nor of the process of buying or selling shares. Stockbrokers need you more than you need them. It is a highly competitive business, with dozens of brokers offering to help you make a transaction – so much so that you can now deal for less than £10. These people are very keen on offering you a service. So regard yourself as being in charge and shop around.

This chapter will allow you to find the service that suits you best. You will, after reading it, be more informed about the different levels of service that you can ask for. For example, do you want to choose shares yourself without advice? In which case you will be looking for a cheap and efficient ‘execution-only’ service. On the other hand, you may welcome advice from a broker. This service will cost more, but not as much as when you ask a broker to manage your portfolio at their discretion.

This chapter also considers what to look for when choosing a broker, and describes what happens behind the scenes after you have instructed your broker to act. Stockbroking has moved so far away from the days of long lunches and high charges that a large proportion of dealing is now done without the need to speak to a broker – via the internet. Again, online dealing is a highly competitive market and you just need a modicum of knowledge to get the most appropriate service for you.

Stockbroker services1

If you wish to buy or sell shares (or other securities) on the London Stock Exchange you have to do it through a stockbroker. There are two types of broker: retail (also called private-client for the private investor) brokers who act for investors; and corporate brokers who act on behalf of companies (providing advice on market conditions or representing the company to the market).

Before being able to deal you will have to register with a private-client broker – this simply involves providing a few details about yourself. The broker will check your creditworthiness (e.g. banker’s reference). Anti-money-laundering requirements mean some extra hassle. To prove you are who you say you are, hard copy documents are required, such as a passport or driving licence and utility bills. The whole process may take two weeks or so. Many brokers then set up an account so that you can deposit money into it. This will reassure the broker that you will have money to pay for a trade in a timely fashion (rather than having to wait for a cheque in the post). There are three main types of service provided by retail brokers (hereafter referred to simply as ‘brokers’): execution-only, advisory and discretionary. Which of these is most suitable for you depends on your circumstances.

Execution-only (or dealing-only) service

Here the broker carries out your purchase or sale order as instructed without offering any investment advice. It is the cheapest way to buy and sell shares. A typical minimum commission is around £10–£20, but can be as little as £6. You need to be trading 20 times each month for this. These figures would apply if you were buying, say, £1,000 of shares. Charges normally rise as the size of order increases. So for a £5,000 bargain £20–£30 is more typical. However, brokers have become so keen to gain business that it is sometimes possible to deal for £10 or so, even for orders of £25,000.

The figures given so far are for online dealing. If you use phone and postal dealing then the typical ranges of fees are somewhat higher: minimum commission of around £15 to £35; for £5,000 bargains, £25 to £80; for £25,000 bargains, £50 to £200. Some brokers charge even when you are not dealing, through monthly or quarterly account fees which can be as much as £10 per month. The justification is that the fee covers the cost of distributing dividends and issuing statements. Shop around. There are over 50 dealing-only brokers in the UK to choose from. Also, once you are registered with a particular broker, it is important to keep an eye on the fee levels charged, as they may change – sometimes for the the worse, sometimes for the better. For example, your broker might introduce ‘inactivity fees’ – taking money from your account every month, but when you trade the broker fee comes out of the inactivity fee. For example, Interactive Investor charges £9.99 per month but ‘we give you back £7.99 credit every month. You can use this to buy or sell any investment’. Interactive Investor is an online service where you trade in the market from your screen without talking to a broker.

My telephone execution-only dealing service with Charles Stanley is more expensive in terms of fees but has the advantage that I can speak with a broker, and while I’m put on hold, they can talk to market makers about getting a better price than the bid-offer spread shown on the screens. This is especially useful when I’m making a relatively large order.

I can say something like ‘I can see that the price of ABC plc is £2.30 to sell and £2.40 to buy. It is a small company with few trades but I want 15,000 shares, but won’t pay more than £2.39. What can you do?’ The reply is something like ‘I’ll see. Can you hold or should I phone you back?’ The broker then discusses my requirements with market makers, trying to get them to keep the price down. A few minutes later I might get a call to say that the order has been fulfilled at ‘238 spot 7’, i.e. £2.387 – my broker has bought within the spread (the bid-offer or bid-ask spread). Many online brokers would have stuck to the standard take-it or leave it prices of £2.30–£2.40, and these prices would only have been possible for only as little as say 3,000 shares – ask to buy more than that and the price rises.

Assuming I can get 15,000, that 1.3p saving per share is worth £195.

Dealing commission is:

| 0.75% on first £10,000 | £75 |

| 0.25% on remainder (£25,805) | £64 |

| Total commission | £139 |

(Charles Stanley also charges me a minimum £200 per year ‘custody charge’).

There are regular savings schemes for investing in shares which offer low brokerage charges. Thus, you might commit, say £20 or £50 per month. When you want to buy, your order is grouped with those of other investors and then executed together several times each month. The buying fees can then be as low as £1.50 (sale fees can be around £10–£20). The disadvantage of these schemes is the inability to trade at a time you think best, but they are a cost-effective way of starting a portfolio.

Execution-only dealing is very popular, with over 90 per cent of investors now in the habit of using an execution-only broker. It is particularly appropriate if you have the time and inclination to make investment decisions on your own. If you have greater confidence in your own research and judgement than the broker’s, then execution-only is the service for you. The downside is that you will not be able to discuss your ideas with a broker. It is also said that you will miss out on hot tips – but then, selecting on the basis of hot tips is not investing but speculating, and is generally unprofitable (according to the academic evidence).

Advisory dealing service

Under this arrangement the broker will give you investment advice, but the decision on whether to buy or sell rests with you. The broker will not take any investment decisions without your authority. This is the more traditional stockbroking service in which the broker knows the client sufficiently well for meaningful discussion of ideas and strategies. It allows the investor to test ideas with someone who is in touch with the market full-time. Also, broker reports on companies or sectors, newsletters or market reviews may be sent to clients. Tax advice and portfolio valuation may also be forthcoming.

The advisory service costs more than execution-only. The broker earns money through charging commission on each deal rather than by charging for advice directly. A typical minimum transaction charge would be between £20 and £50. This rises to £40–£100 for £5,000 deals and £200–£300 for £25,000 transactions. Alternatively, transaction charges can be kept low, with the broker charging an annual fee, say 0.85 per cent of the value of the portfolio. The cost varies tremendously from broker to broker, as does the quality of the service. Some advisory brokers go further for their clients than others. While many will wait for a call from an investor before offering advice, others are more willing to initiate the contact.

Taking the initiative one stage further, some brokers now differentiate between their advisory dealing service and their advisory portfolio management (or just advisory managed) service. The advisory dealing service is taken to be a reactive one in which the broker gives advice after being asked for it on specific shares, whereas under the advisory portfolio management service the client is contacted once or twice per month with advice on their portfolio and its constituent shares. This is usually when there is a good reason, such as news on a particular company, sectors, etc.

With the advisory portfolio management approach, the broker is knowledgeable about the client’s overall financial profile and can advise appropriately. One drawback with this type of arrangement is that the investor might be encouraged to deal frequently – good for brokers but, more often than not, very bad for the wealth of investors. Fees mostly based on the size of the portfolio of assets rather than on transaction fees removes some of the incentive for the stockbroker to churn your portfolio (make unnecessary trades to generate fees – nowadays churn is less of a concern given the pressure applied by the regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, to ensure that stockbrokers’ compliance offices are monitoring accounts to prevent churn – they ask their managers to justify the level of trading on an account). It also gives an incentive to increase the size of the pot. Thus, the broker may recommend going into cash rather than sticking with shares at times of market exuberance, so that total asset size is preserved.

Discretionary service

Under this type of service, the broker is paid to manage the investor’s portfolio at the broker’s discretion. Thus the broker takes decisions on which shares to buy and sell without consulting the investor on each deal. The client is informed after the event. Giving the broker authorisation to act before getting the investor’s approval allows the snatching of opportunities as they arise in fast-moving markets. One of the common complaints of advisory brokers is that their clients are not always available – oddly enough, they like to live a life beyond their portfolio – and so fleeting chances are missed as permission to buy is not given quickly.

Furthermore, many clients simply do not want to spend time managing their portfolios. They don’t want to devote effort to developing investment skills. They therefore place their money in the hands of professionals. Prior to running your portfolio, the broker will meet you to gain an understanding of your particular circumstances, your investment aims and any restrictions you would like to place on the portfolio (e.g. no investment in tobacco or arms).

Only around 5 per cent of UK investors have discretionary portfolio management accounts with brokers. One of the reasons for the low take-up is that brokers generally insist on a minimum portfolio size of £50,000. Some set the minimum at £100,000 or even higher. The average discretionary portfolio is around a quarter of a million. Another reason is the cost of the service. Not only are investors usually charged commission (at about the same level as advisory clients) on each transaction but they are also charged an annual fee related to the total value of the portfolio. This is generally between 0.5 and 1 per cent. Some brokers have high dealing charges (1.25 per cent or more) and low annual fees, whereas others charge a mere £20 or so for each transaction but load the costs on to the annual fee, while a few now offer a fee-only service.

The amount you pay generally depends on the frequency of trading – the discretion over which you have granted to the broker. Be on your guard against churning. It is disturbing that very few brokers offer to charge on the basis of the returns they achieve.

The following article discusses concern about fees charged by discretionary managers. Since this article was written, new rules have been introduced (in 2018 under MiFID II) requiring wealth managers to produce a full annual breakdown of the fees and costs their customers incurred in the previous 12 months. We await to see clients’ responses when they see fees and costs, in both pounds and percentages, and whether everything will truly be revealed (or they’ll be scandals of hidden charges).

Article 4.1 - Discretionary managers urged to reveal charges

By Judith Evans

Discretionary fund managers are failing to disclose details of their fees and holdings which ought to be crucial to financial advisers’ decision-making, according to a new report.

Discretionary portfolios, in which managers handle client money on investors’ behalf — including rebalancing portfolios and making asset allocation decisions — should face the same transparency requirements as mutual funds, according to research by the consultancy The Lang Cat. Advisers have increasingly recommended the use of discretionary portfolios to clients. The Lang Cat tried to establish whether advisers were generally choosing suitable products in this area for clients.

We found an almost total lack of rational behaviour on the part of a number of adviser respondents, and systemic issues on the supply side,” said Mark Polson, principal at The Lang Cat. Nearly half of advisers who recommend discretionary products told The Lang Cat that it was “quite hard” or “very hard” to establish total costs. The Lang Cat said that a full comparison of different discretionary portfolios was “nigh on impossible” but estimated average total annual charges at 2.08 per cent in its report. Other estimates have placed this higher, including a survey by Numis, which suggested some clients might be paying up to 7 per cent.

Wealth managers, who run portfolios directly for their own clients but may also offer products to external advisers, say they already disclose most charges in percentage form on “rate cards” to new clients.

Nick Hungerford, founder of the online wealth manager Nutmeg, said he had spoken to new clients who were unaware they had been charged trading costs by their former wealth manager, although it is standard practice to use client money to pay for the costs of trading. He said that companies failing to disclose these costs were “stuck in the 19th century”.

The Lang Cat said the lack of cost disclosure goes in tandem with other problems, such as a lack of holdings information and questions over performance. The consultancy looked at a sample of discretionary portfolios over rolling three-year periods and found that no more than 11 per cent outperformed the FTSE All-Share index at any point, while none outperformed the FTSE 250.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 30 January 2015.

© The Financial Times Limited 2015. All Rights Reserved.

Choosing a stockbroker

There are many ways of finding a stockbroker. The London Stock Exchange (www.londonstockexchange.com) publishes a complete list of its members. The Personal Investment Management and Financial Advice Association (PIMFA) provides information on its website www.pimfa.co.uk, including stockbrokers’ contact names, addresses, telephone numbers and an outline of the kinds of services offered. Investors are regularly surveyed for their opinions on broker performance and costs in investment magazines such as Investors Chronicle. Investors also find brokers through personal recommendation.

Choosing a broker means selecting the right combination of cost and services. The following selection criteria may help you draw up a shortlist of brokers and make a final selection:

- Charges: Of course, the lower the commissions for trading the better, but you should allow for the possibility of improved service at extra cost. An important aspect of improved service is the effort put into ‘price improvement’ which is taking action to obtain better prices than the current bid and offer prices shown on the screens, through, say, haggling with a market maker. The charging structure will make a big difference to your choice of broker. For example, an investor who does not want to pay for advice and trades many times each month with bargain sizes of around £5,000 will prefer a broker who charges a low fixed rate regardless of bargain size, say £20 each time. Another trader, who buys and sells £1,000 of shares, may prefer a broker who charges a percentage of the amount of the trade, say, 1.0 per cent. If you are a buy-and-hold investor, with few transactions, commission costs will not be a great concern. But if you are very active the charges mount up dramatically. Then you may opt for the cheapest mode of transacting – usually online. This might be fine for the most liquid shares with narrow bid-offer spreads, but for infrequently traded shares the bid offer spread can be 10% or more and a telephone service broker might be able to negotiate a better price.

- Location: The possibility of being able to talk to a broker face to face may lead investors to favour a local broker. This can be particularly valuable for discretionary and advisory portfolio management, where the broker needs to know the investor’s circumstances and investing objectives. Local brokers may also be knowledgeable about companies in the region.

- Contact: In surveys investors usually place the ability to contact brokers at the top of their worry list. There are many complaints about telephone lines being busy when a client wishes to deal. People can be put on hold for 20 minutes or more. This can seem like an eternity when you are trying to sell and the market is falling like a stone. Brokers are also criticised for not calling back when they promised to do so. Online orders are often executed very slowly at busy times, as the IT systems suffer from overload. Unfortunately, this is one of those factors that you do not really find out about until you experience it. However, it might be worth asking other clients of your shortlisted brokers if they have any complaints. It could be useful to be able to switch to telephone dealing if the online system is down, and vice versa. So consider a broker that gives you this flexibility.

- Administration: The second factor most complained about is the quality of the administration. Record-keeping is sometimes poor, as is the administration of dividends and taxation matters. The paperwork may reach the investor weeks after the event. You do not have to put up with this as other brokers are highly praised for the speed and efficiency of their administration.

- Expertise: You need a broker who is well resourced, has access to high-quality external data and attracts talented managers. This is especially important if you are asking for portfolio management services. You do not want your nest egg managed by a graduate trainee trying to learn on the job. Ask what experience the firm has in managing portfolios of the type and size you have in mind.

- Performance: Unfortunately independently constructed league tables of portfolio managers’ performance are not available and so comparison is all but impossible. Brokers do provide statistics, but you must view them with caution.2 Recommendation may be your main hope.

- Interest: Brokers hold money in cash accounts on behalf of investors. Some of these accounts offer miserly rates of interest, if anything. Those depositing substantial sums with a broker need to ask what rate of interest will be received prior to the purchase of shares. Also, if you need temporary credit, what limit will the broker allow you to go up to?

Here are some other questions you might ask:

- Is the firm authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority? Your assets may have little protection if it is not. Try www.fca.org.uk, or telephone the FCA consumer help line (0800 111 6768 freephone).

- What insurance does the brokerage have in place against fraud or negligence?

- What can you expect in terms of newsletters, company analysis, sector analysis or regular portfolio valuation?

- Does the broker offer a dealing service for securities other than UK listed shares, such as overseas shares, traded options and bonds?

- If you are trading online, what internet security features are in place?

About half of UK investors open accounts with more than one broker as it does not cost anything to open two or three accounts. One reason for multiple accounts is to avoid the frustration of not being able to contact a broker – if one is not picking up the phone another might. Investors may also require specific services that their main broker either does not provide or supplies at a higher price.

Finding prices and other information

So, you’ve chosen your broker and you’re getting ready to invest, but where can you find share prices and other information about a company? One source is the daily newspaper coming through your letterbox. The only problem with this is that the information is quite old – at least 12 hours. The internet has been a boon for investors looking to gather information and it is very handy for trading shares. In the past 20 years there has been a revolution in the way investors discover key data about a company and select shares.

Prior to the online delivery of information traders had to write to or phone a company to get a copy of the annual report and charts of share prices were only for those in the City with a Reuters screen and it took an age for company announcements to trickle through. Today a quick online search delivers company reports going back ten years (or more) as well as an astounding array of stock market statistics and views on companies: from when directors bought shares in their own companies to share price histories to bulletin board discussions about the company’s latest product.

The company’s website

The place to start is the website of the company you are interested in. There are two aspects to this. First, how does it present itself on the internet and what can you glean about the underlying business strengths in terms of customer appeal, etc. Second, the financials: how has it been performing with regard to making profits for shareholders? And how strong is the financial structure (e.g. does it have too much debt and is therefore too risky)?

You can gain a feel for the quality of the company’s communication efforts at this point as well as gain some insight into its competitive position benchmarked against other players in the industry. Of course, you are reading a cleaned-up PR version, and so a reasonable amount of scepticism is required, but by combining this information with material from other sources you can start to build a picture.

A good antidote to corporate PR is to search the company name or its brand products and add the word ‘reviews’ to see what customers thought of it. If a lot are upset with the company you may decide to pass on this investment. There are also websites, such as Glassdoor and Indeed.com, which gather employees’ views.

Those companies with a high consumer focus (e.g. Vodafone and Marks and Spencer) have websites mostly concerned with selling products or an image of the firm to the public. Simply searching using the company name, you may find it difficult to discover the material directed at investors. To get there more directly I usually search on ‘investor relations’.

Newspaper websites

Many broadsheet newspapers supply articles free to anyone who visits their websites and you will be able to search for articles going back many years. The most sought-after financial papers, the Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal, allow you access to many parts of their sites for free but restrict your ability to search their archive of articles to a limited number of articles in any given period. If you want more you will have to subscribe.

Financial websites

Specialist financial websites offer much more than share prices so you can learn a tremendous amount about a company. Furthermore, you do not have to limit yourself to using just one. By registering with half a dozen (taking two or three minutes for each), you can access an even wider range of information. The only downside is they will send you junk mail – frequently. Here are some of the players in the business – consult their websites for current services.

| Financial websites | |

| www.advfn.com | ADVFN |

| www.youinvest.co.uk | AJ Bell Youinvest |

| www.digitallook.com | Digital Look |

| www.ii.co.uk | Interactive Investor |

| www.londonstockexchange.com | London Stock Exchange |

| www.moneyam.com | MoneyAM |

| www.morningstar.co.uk/uk | Morning Star |

| www.fool.co.uk | Motley Fool |

| www.uk.finance.yahoo.com | Yahoo! Finance |

Getting the most out of financial websites

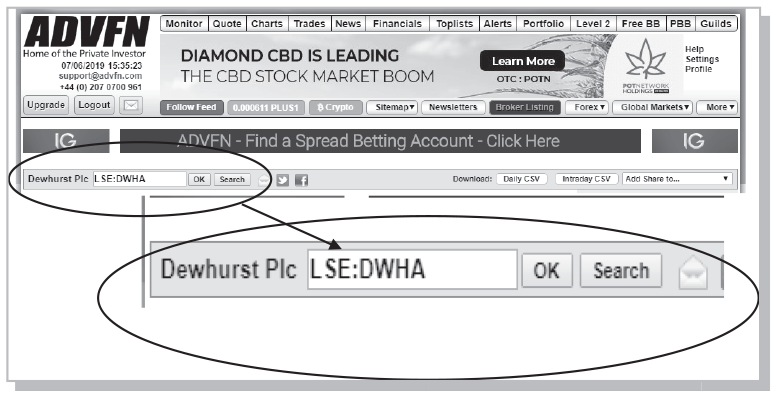

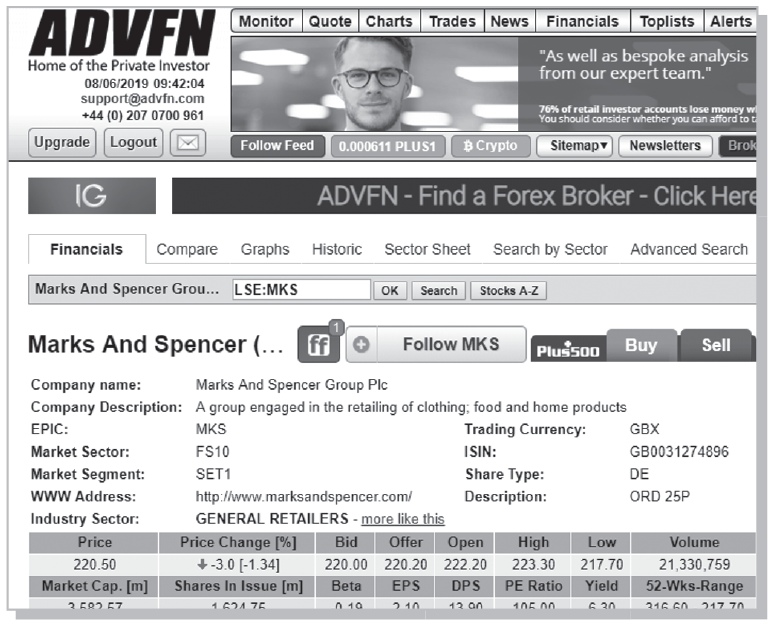

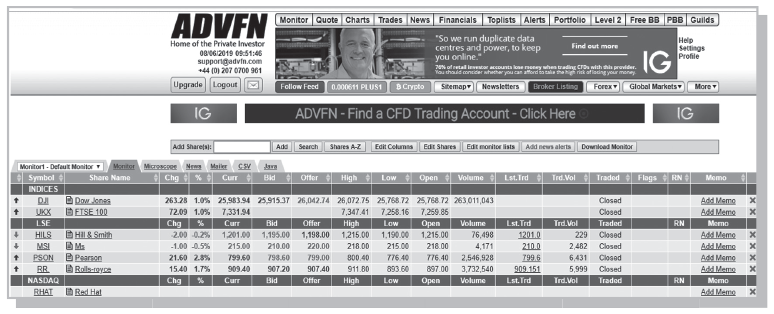

Figure 4.1 shows the home page of ADVFN. Other websites have similar features, with some better than others on particular aspects. I’m not promoting ADVFN (although I do post my investment newsletter ‘Deep value shares’ there). I just need to make use of one of the major suppliers to illustrate the amazing variety of information available.

Figure 4.1 The home screen for ADVFN

After logging in, you may want to look up the price of a particular share. Click on the ‘Quote’ button (top left of screen) shown below.

Figure 4.2 Home screen with a focus on the ‘navigation bar’ showing the quote button

The page that this takes you to allows you to search for a particular company.

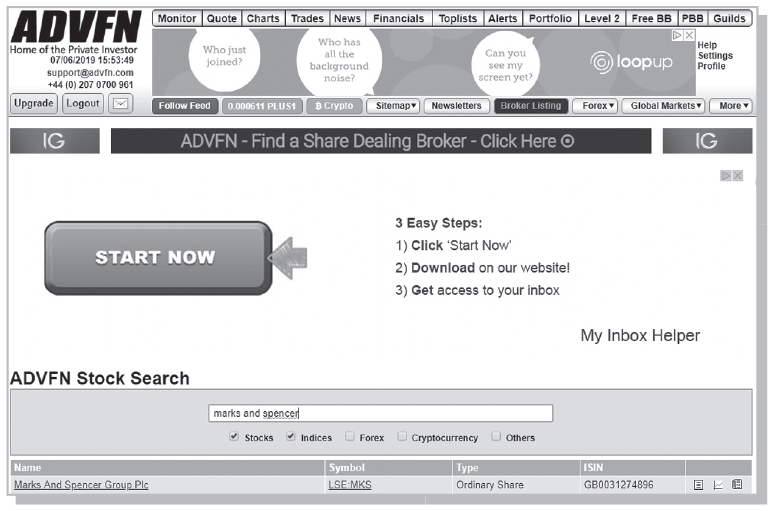

Operators in the markets (brokers, etc) reduce the names of companies down to very short ‘stock symbols’ or ‘codes’. They are also called tickers and TIDM codes (but they are often called by the old name, EPIC codes). So, for example, Marks and Spencer is reduced to MKS. Most of us do not know the codes that we need, but we can look them up. So, on the quote page if you click on ‘Search’ a screen similar to the one below will appear.

Prices

Let’s search for Marks and Spencer. As you type Marks and Spencer in the box it appears below, complete with its TIDM symbol. Click on the name of the company to display some information – as shown below.

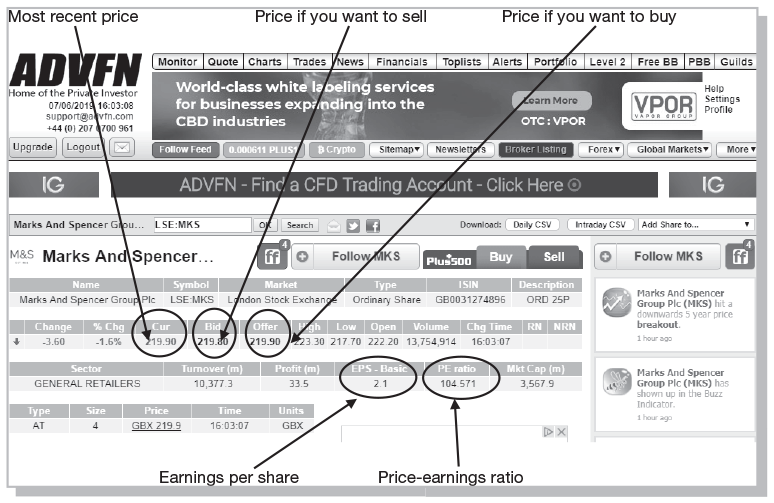

Figure 4.5 shows some of the data displayed on the quote page for MKS. There is the latest traded price ‘Cur’ (meaning current) at 219.90p. The offer price if you want to buy is 219.90p, whereas if you are interested in selling the bid price is 219.80p. Also displayed are the highest and lowest prices so far today (223.30p and 217.70p). Between the stock market opening at 8 a.m. until 4.03 p.m., when the screenshot was taken, 13,754,914 shares were traded. You are also presented with some financial data: the last 12 months of sales at MKS’s shops (£10,377.3 million), annual profit, earnings per shares (EPS) in pence, price–earnings ratio (see Chapter 12 for a description of EPS and PE ratio), and the current market value of all MKS’s ordinary shares, that is a ‘market capitalisation’ of £3,567.9 million. The final line shows the most recent trade to go through: four shares at a price of 219.90p.

News

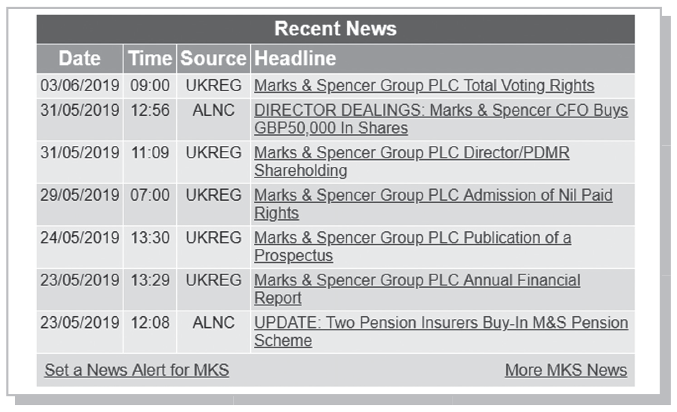

Scrolling down that page you will come across the ‘Recent News’ section. All the financial websites supply company announcements and other news. The news for MKS on ADVFN is displayed below.

Figure 4.6 Obtaining news on the company – an ADVFN screen

Clicking on the headline will bring up the full news story. The system carries news and announcements going back many years. So, for example, if you wanted to find out if periodic director statements on the progress of the company proved to be accurate or generally over-optimistic you can read both the statements going back ten or more years and the subsequent reported results.

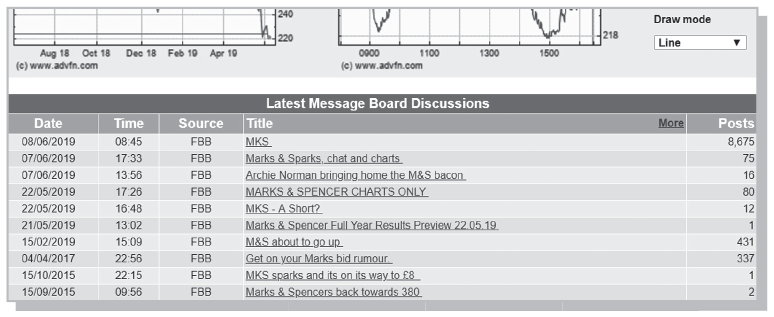

Bulletin boards

By scrolling down the quote screen for Marks and Spencer you can see the message/discussion board or ‘bulletin board’ – see Figure 4.7. This can be an important source of information. The entries are written by anyone registered with the website. Through these it is possible to correspond with like-minded investors, which helps to make the game of investing less lonely as well as exposing you to alternative views.

People that post on these threads usually adopt nicknames. Some are well informed and can add to your knowledge of the company, but beware as others know little and are trying to ramp up or push down a share, or are there just for a rant. Be particularly wary of those who claim they know a takeover bid is coming or the directors are about to sell a large chunk of shares or they have some other inside information. They are trying to get a share price movement so that they can make money for themselves. If they really had this inside knowledge do you really think they would share it with you? And anyway insider dealing is illegal.

Tip: it is worth looking at a number of website discussion boards to help build up background knowledge.

Figure 4.7 A discussion board

Useful websites for discussion boards

| www.advfn.com | ADVFN |

| www.ii.co.uk | Interactive Investor |

| www.moneyam.com | MoneyAM |

| www.fool.co.uk | Motley Fool |

| www.uk.finance.yahoo.com | Yahoo! Finance |

Financial data

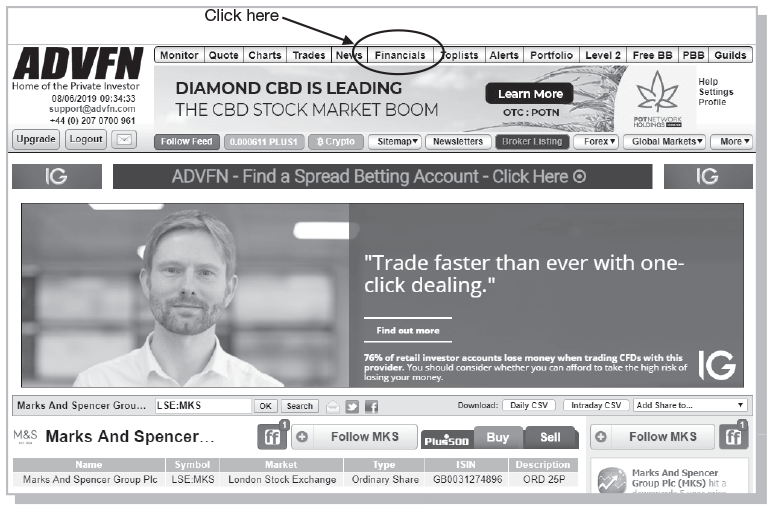

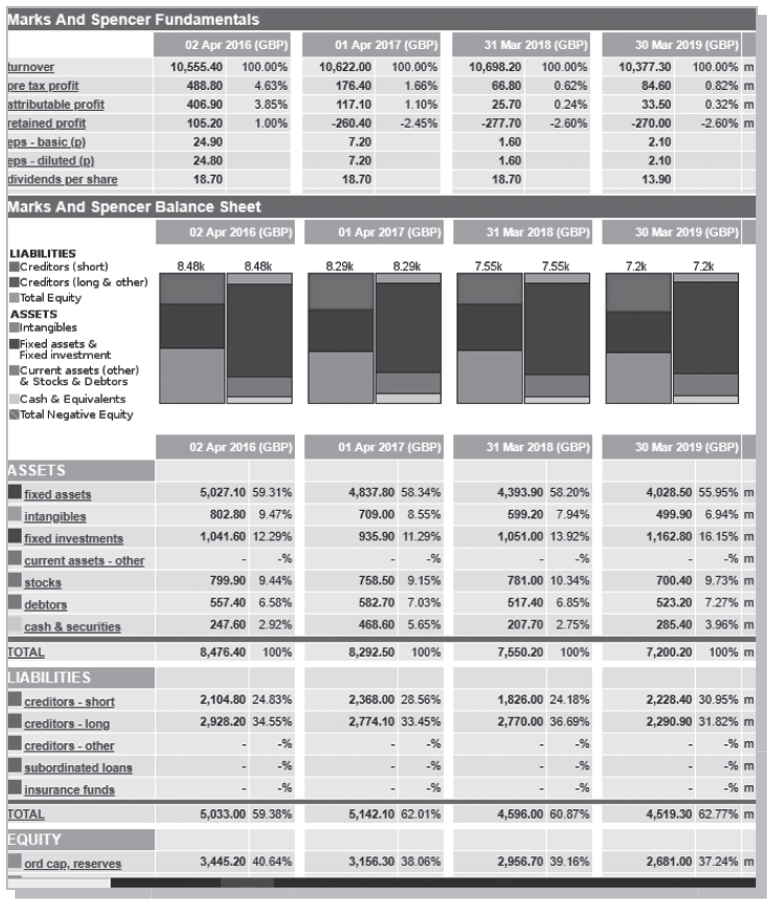

On the ribbon at the top of the page there is the ‘Financials’ button – see below.

Clicking through you’ll see a screen like the one in Figure 4.9. A useful feature on this page is the ‘more like this’ button which will take you to a list of companies in the same industry on the LSE. It is always important for an investor to be aware of the relative strengths of competitor firms. By following the links you can discover a wide range of information about some of the companies that compete. However, you may need to take a more international perspective because the company’s main competitors may not be quoted on the LSE. For example, Rolls-

Royce Aero Engines compete against US rivals.

Scrolling down the Financials page we find accounting data.

We do not have space to discuss all the different financial ratios and measures displayed on a page like this, but these are explained in Chapters 11, 12 and 13.

Monitoring

Going back to the home screen for ADVFN (Figure 4.1 earlier) you can see a string of buttons going across the top – see below.

The ‘Monitor’ button allows you to track a number of companies and indices.

Once a company is on your monitor list you merely click on the company name to obtain more detail, without having to look-up its code. You can also see if there is any recent news about the companies on the list. To add companies to the list just find the relevant code.

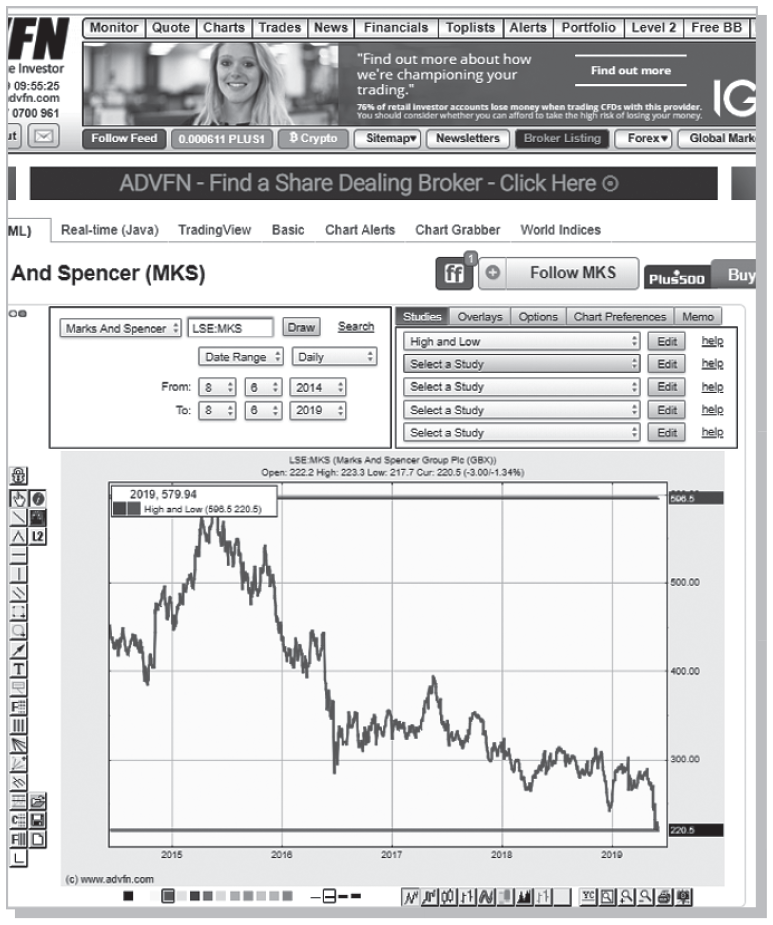

Share price charts

The ‘Charts’ button at the top of the home page allows you to draw share price charts.

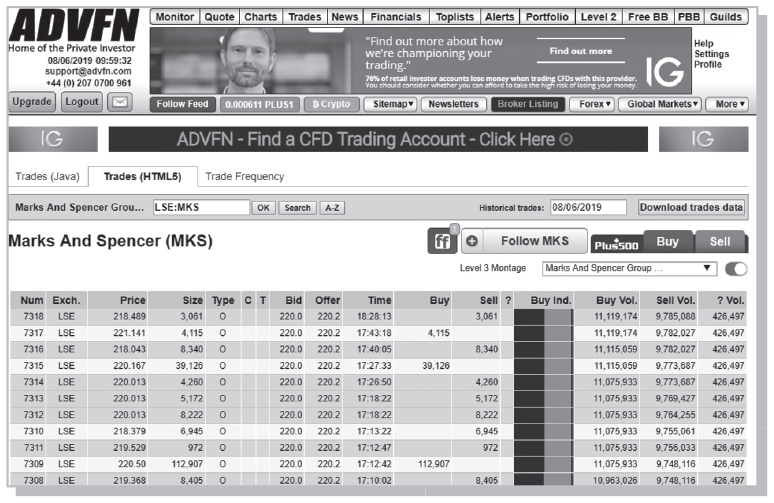

A history of trades

The next button, ‘Trades’ (in Figure 4.11), allows you to see the actual deals that have been made in the market. With M&S there are share trades every few seconds. Other (much smaller) companies may go days without a single trade. This page is very useful if you are about to buy or sell shares as you can see what people were willing to accept. It’s also fun to see your trade go through on this list. It is possible to see the trades of days past as well as the current day – click on ‘Historical trades’ white box.

Figure 4.11 The main buttons to click

Figure 4.12 Monitoring a selected group

News

The ‘News’ button (see Figure 4.11 earlier) brings you to a page displaying the major news stories of the day (e.g. a merger bid). By inputting the code for the company in which you have an interest you can see all the past announcements, etc. An alternative use for the news button is to get a continuous stream of news as it is released from all companies on the market – this is updated as you look at it.

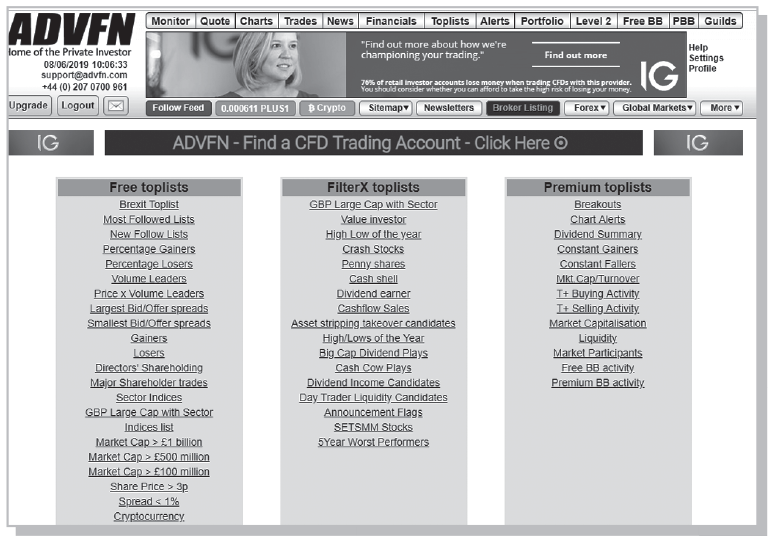

Toplists

The ‘Toplists’ button (see Figure 4.11 earlier) is a great way of selecting, from all the shares on the market, a shortlist of companies based on key criteria, such as those that have produced the best or the worst five-year returns. You can then filter out those that, say, were unprofitable last year, or those with a market capitalisation greater than £100 million, and so on. Figure 4.15 shows only a few of the factors that can be used to rank and separate companies.

Figure 4.15 Filtering and ranking companies on the markets

Alerts

The ‘Alerts’ button (see Figure 4.11 earlier) permits you to programme the system to tell you if a particular threshold is reached – if the share price of M&S falls below £1.80, or an event occurs. There are three types of alerts: share price alerts, news alerts and bulletin board alerts. In each case, you can ask the financial website to send you an email message when something happens.

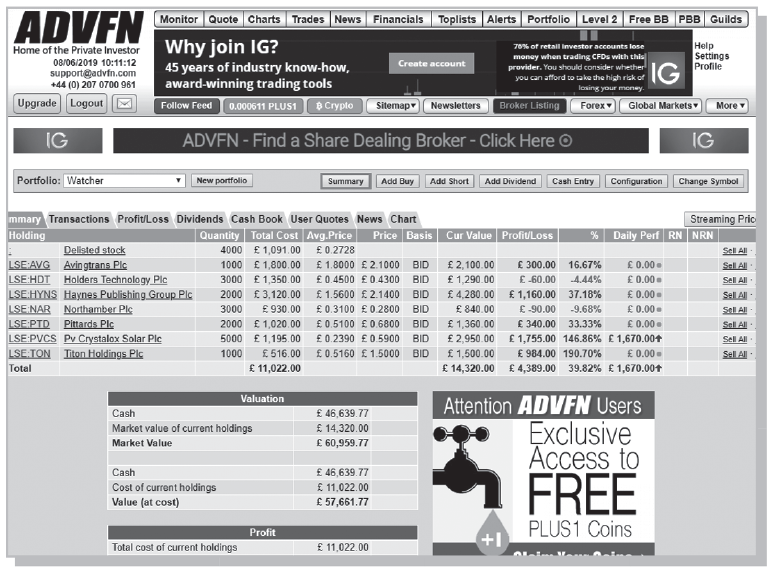

Creating real and virtual portfolios

The ‘Portfolio’ button (see Figure 4.11 earlier) allows you to set up a number of hypothetical or real portfolios and then follow the shares through time. Figure 4.16 shows that the portfolio gains and losses are totalled automatically. You can click through from the company names in the portfolio list to more detailed information on the company.

Figure 4.16 A portfolio screenshot

You can create as many portfolios as you want. So you might want to follow the performance of shares with low price–earnings ratios and set up a series of such portfolios every six months and follow their progress over the subsequent years. Or you might like to set the system to follow the progress of companies selected on the basis of the investment principles of Warren Buffett.

When checking your portfolio, beware of the psychological problem we humans have when it comes to what behaviouralists call ‘narrow framing’. In this context we lose sight of the bigger investment picture and feel pain as a result. On any one day or month there is a roughly 50:50 chance that your portfolio will be up or down. It turns out that we humans feel a loss much more keenly than a gain.

So if we are continually looking to see whether we have made money in the past few hours or lost it we will suffer the pain of loss regularly and this will outweigh the pleasure we feel on up-days. This can lead to some bad decisions as we go on a desperate search for short-term fixes to feel the pleasure of a gain.

Do not narrow frame – see the bigger picture, which is that shares generally give a satisfactory return over a number of years, but there will be many bumps along the way. Do not be distracted and depressed by the bumps.

Be a long-term investor in good companies. Consider whether it makes sense to look at your portfolio returns every day. Yes, look at company performance and other data relevant to that performance (e.g. technological change in the industry), but not at stock market ups and downs. This is one of the key lessons from the great investors Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett3

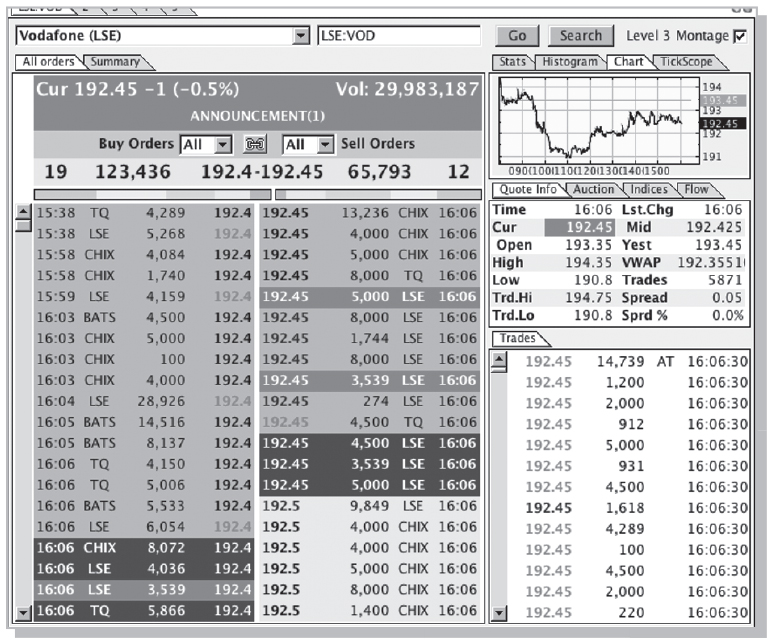

Level 2 prices

Brokers and many financial websites offer Level 2 (or Level II) prices. Level 2 allows you to see on your computer the orders for shares that other traders are putting into the LSE’s system, with prices they are willing to pay or sell for, and the quantity they are willing to trade. We saw in Figure 4.5 Level 1 data: simply bid and offer prices, price of last trade executed, current day’s high and low, percentage change from the previous close of trading, the volume traded, etc.

Having Level 2 permits a greater understanding of the current supply and demand conditions because it allows the private investor to see the current unfilled buy and sell orders, which can change in front of their eyes as the system continuously streams updates. This provides a better understanding of how the share price is derived and helps in timing the placing of an order. A screenshot of Level 2 prices is shown below.

Figure 4.17 A level 2 screen

Level 2 is useful if you are a regular trader, but for many long-term, buy-and-hold investors who trade infrequently it seems quite expensive at £48 or more per month. (If you trade frequently through one broker, say 30 trades per month, they may set you up with Level 2 for nothing, but you’ll be paying them a lot every month in dealing charges.)

Directors’ dealings

Another piece of the information jigsaw you might find useful is whether the directors of the company have been buying or selling its shares. Many investors take a purchase as an indicator of a positive opinion of the firm’s prospects by someone with superior access to information. If they are spending their own money on the shares perhaps there is reason to think they might be undervalued. On the other hand, a sale may not be as negative as it first appears – school fees might need to be paid, or rational diversification is taking place. Much depends on context. Within the company news sections of financial websites (as in Figure 4.6) you find details of all the director purchases and sales going back many years.

What happens when I buy or sell shares?

Now you’ve reached the exciting moment of actually buying (or selling) a share. There are many ways you can do this, the most common being via the internet or telephone. When you telephone your broker, you will be asked your name, account number and a couple of security questions e.g. date of birth. Then you will tell the broker that you want to trade in the shares of a particular company and ask for the current price. The broker will give you not one price, but two. The first is the price at which you can sell the shares, the other is the price at which you can buy.

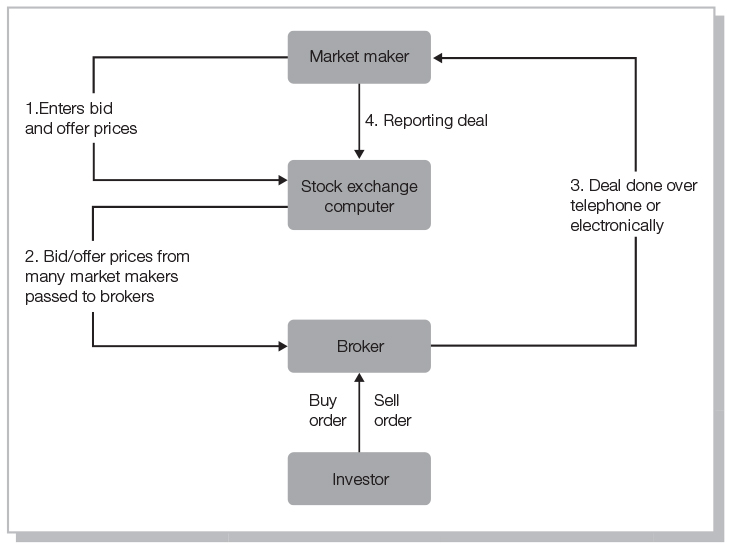

To start with, we are going to look at the quote-driven method of trading with market makers at the centre of the process. What happens with quote-driven trading is this: when you mention the company name the broker immediately punches into his computer the company code.

What I’m going to describe now is the London Stock Exchange Automated Quotations (SEAQ™, pronounced ‘see-ack’) system because it neatly describes the market maker-based system and was the backbone of the UK market for decades. It’s easier to understand than modern SETSqx, which will be described once the basics of quote-driven trading are understood. But note that shares are no longer traded on SEAQ, only bonds.

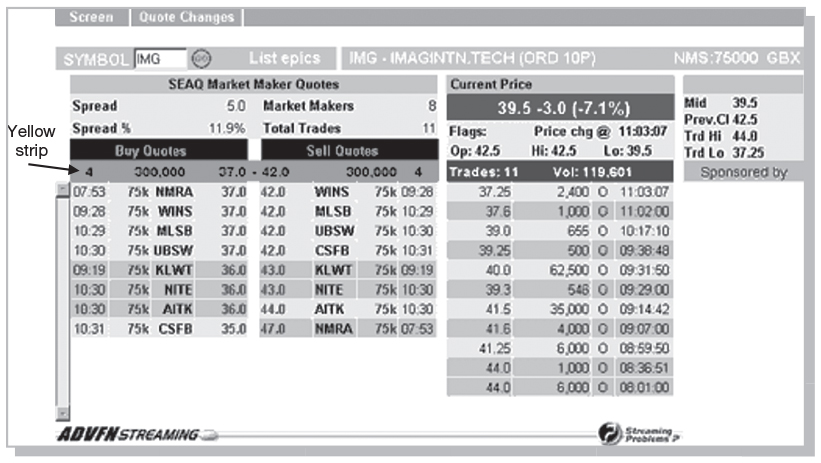

The SEAQ is a computerised system for distributing the prices offered by market makers. So within a second of you mentioning your interest in the company the broker sees on his screen all the prices that different market makers are willing to pay as well as all the prices they are willing to sell for.4 A typical SEAQ screen is shown below.

Figure 4.18 A typical SEAQ screen

Here are some explanations of what is on display above:

- NMS 75,000: The normal market size (NMS) for this stock is 75,000 shares. This is also called the Exchange Market Size, EMS, which is the minimum quote size at which market makers are obliged to trade. EMS is set by London Stock Exchange for each security at around 1–2% of the average daily trade.

- Spread: This is the difference between bid and offer. In this case it is 5p or 11.9% of the offer share price of 42p.

- Total Trades: This is the total number of trades that have occurred so far today – there have been 11.

- Current Price – Mid 39.5: This tells us what the current mid price is. This is based on the middle price between the current bid and offer. The colour denotes the current mid price compared with last night’s close. Blue means up, red means down and green means no change.

- −3.0 1 −7.1%2: This is a calculation based on the current mid price compared to yesterday’s closing price for this particular share. The mid price is minus 3.0p, or −7.1% on the day so far.

- Vol: The total number of shares that have traded so far today is 119,601.

There are about 36 equity market makers but not all of them choose to make a market in the company displayed in Figure 4.18. This screen shows that eight market makers (from NMRA to AITK) are offering prices. The fact that there are a relatively large number of competing organisations willing to quote prices indicates that this is a large company with a liquid secondary market in its shares. Small companies may have only two or three market makers willing to display prices. The ‘bid’ price is the price at which the market maker is willing to buy. So, in the case of the market maker NMRA the bid price is 37p. The ‘offer’ price is the price at which the market makers are willing to sell – NMRA offers these shares at 47p. The spread between the two prices represents a hoped-for return to the market maker.

It can be confusing and time-consuming for the broker to look at all the prices to find the best current rates. Fortunately they do not have to do this as a ‘yellow strip’ is displayed above the market makers’ prices, which provides the identity of the market makers offering the best bid and offer prices (these are called ‘touch’ prices). Market makers NMRA, WINS, MLSB and UBSW present the best price, at 37p, if you want to sell. There are four market makers offering 42p if you want to buy. So, your broker will tell you 37–42p over the telephone. If you are happy with 42p you would then instruct your broker to buy, say, 5,000 shares.

The market makers prices are quoted as ‘firm’ prices. That is, the LSE insists that the market maker trade at these prices if a broker (investor) has been attracted to do a deal based on the posted prices. They cannot change them when they are contacted by the broker if the transaction is below the exchange market size or EMS (also called normal market size or NMS). (This is set at 1 to 2 per cent of the average daily customer turnover.) It is displayed at the top of the screen. For deals larger than the EMS the market maker is allowed to change prices and will give the broker a price when he calls. Of course, prices can be changed at any time so the market maker can adjust in response to the weight of buying and selling pressure, and in response to what other market makers are offering. In this case the EMS is 75,000, so your 5,000 share order does not require a special price quote and you will be able to trade at the prices shown (or better).

Next, the broker (or the website) asks what type of order you would like to make. You have two main options:

- You could ask your broker to execute your order at best, also called a market order. This means that the trade is completed immediately at the best price available. If the broker is unable to obtain the shares at the price he quoted to you (because, say the market makers’ quotes change in the few seconds or minutes between you saying you would like to buy and the market makers being contacted), you may end up paying more than you thought (or less). Also, many brokers try to obtain prices ‘inside the price quotes’ (within the spread) – they ‘price improve’.

- If the uncertainty of dealing at best is too much, you can place a limit order. Here you specify the maximum price at which you are willing to buy or the minimum price at which you are willing to sell. The order can stay on the system until it is fulfilled (up to 90 days) or until cancelled (good-till-cancelled order) or until a fixed expiry date is reached regardless of whether it has been completed. One of my brokers usually suggests putting the limit on for a week. If the market moves to my limit all well and good, the broker does the deal without me needing to phone up again (or input anything on my online account). If the market has not moved to my price limit the broker will take the order off their system once the week is up – and there is no charge for this.

There are some more exotic alternatives:

- An execute and eliminate order means that the transaction is completed in part or in full immediately. A price limit is set by the investor. If not completed immediately the order expires on the spot. If only some of an order is fulfilled the remainder expires.

- With a fill or kill order a maximum (minimum) price is stated. If the deal cannot be executed in its entirety at this price or better, the entire order expires.

- With a stop-loss order your broker is instructed to sell shares you hold if they fall below a stated price. The idea is to protect your portfolio against a dramatic and sudden downward move, thus protecting the bulk of your funds. Personally, I do not see the point in them. If you are ‘investing’ rather than ‘speculating on market moves’ then you will have thoroughly analysed the company and judged it a good one to hold at that price based on its strategic position, quality of managers, earnings per shares, etc. If the share falls then it is an even better buy. If the fundamental strengths of the company have deteriorated then this may induce a sell, but not a fall in share price per se.

Now the broker has all the information needed to enter the market place and buy shares. A good broker will read back your order to you: ‘Buy 5,000 shares in ABC on an execute or eliminate basis with a maximum price of 36p.’ They will then ask you to confirm that you would like them to go ahead (telephone calls are recorded). At this point you are making a legal commitment to enter the transaction with the broker.

When your broker hears that you wish to go ahead you can either stay on the line to await confirmation that the order has been completed or ask the broker to call you back. Next, the broker telephones the market maker offering the keenest price and a deal is struck verbally or via computer systems.5 With online trading you will see a clock counting down from 20 seconds or so. If, before the clock reaches zero, you click on the trade button the deal will go through at the price quoted.

All trades are reported to the central computer at the heart of SEAQ and disseminated to market participants within minutes.6 This gives a great deal of transparency to the system, allowing everyone to see a range of recent prices, as shown below.

Figure 4.19 The quote-driven system for trading shares

While the traditional way of trading is for brokers to telephone market makers, today the majority of private investor trades are made through retail service providers (RSPs). Telephone and internet-based execution-only stockbrokers charge a very low price for each trade. One of the ways in which they keep costs down is to put small trades (usually those under the exchange market size) through an RSP network. Brokers may have five to ten RSP relationships. The RSPs relieve the burden for market makers and brokers of having to pick up the telephone to strike a deal for orders of merely a few hundred shares. An electronic system polls the market makers that are acting as RSPs – and the electronic order books of the LSE, such as the Stock Exchange Electronic Trading System (SETS), which is discussed later – for their bid and offer quotes. The investor is then told the most competitive RSP quote via the computer screen (if dealing online) or via the telephone. Typically, the two-way quote is valid for 15 to 30 seconds. The RSP network automatically and instantaneously executes the order electronically, saving time and money. Furthermore, the RSP network may allow for a slight improvement in the quoted price displayed on financial websites – better than the price shown in the yellow strip (price improvement service). For orders larger than the EMS it is usually preferable for the investor to get the broker to talk directly to the market maker.

If trading online, within a few minutes you’ll receive a message (on the broking system and/or to your email inbox) with a contract note. With telephone dealing the contract note usually arrives the next day in the post. This will state the price, the time of the deal, the number of shares, the broker’s commission and the charge of 0.5 per cent of the value of your purchase in stamp duty for Main Market shares (this is a form of taxation that applies to purchase only, but not to AIM shares). Check the details to make sure they match your expectations and file the note so you have a record (useful when it comes to filling out a tax return).

If you have a broking account, then the broker will debit (credit) the account two business days after the transaction.

If you have opted to receive share certificates (see below) then these will be sent to you by the registrar of the firm in which you now hold shares.

An order-driven trading system

We now turn to the approach used by the London Stock Exchange for the trading of larger more liquid shares on the Main Market and on AIM. This was introduced in the 1990s because there was criticism of trading systems based on market makers quoting bid and offer prices. Investors comment that with the quote-driven systems the middle man’s (the market maker’s) cut comes from them. Wouldn’t it save them money if buyers could trade with sellers at a single price to eliminate the loss of the bid–offer spread?

Well, many stock exchanges in the world operate this type of order-driven trading system. These markets allow buy and sell orders to be entered on a central computer, and investors are automatically matched (they are sometimes called matched-bargain systems or order book trading). The LSE order-driven service is known as Stock Exchange Electronic Trading System (SETS). This now operates for about 900 particularly liquid, frequently traded shares, including the largest 600 or so on the Main Market and the most liquid AIM and Irish securities.

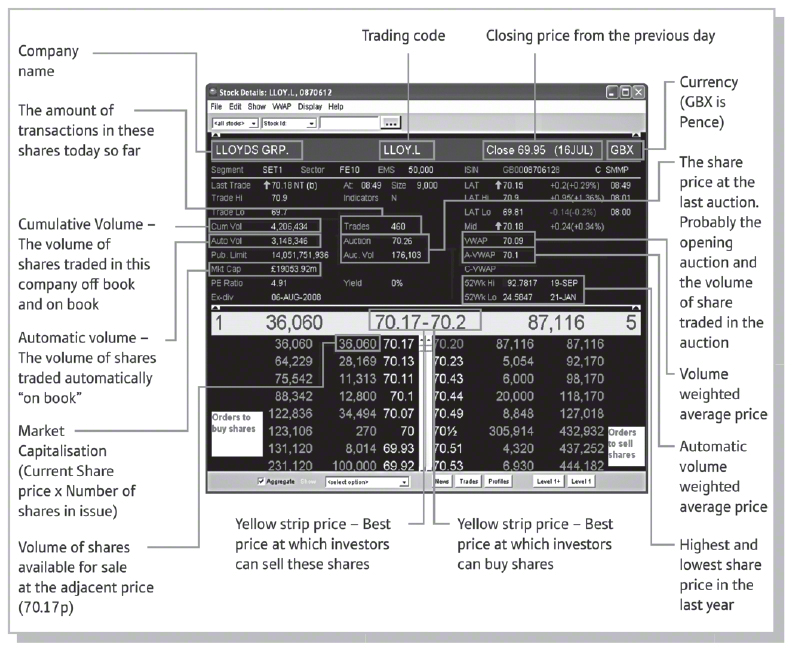

SETS is a computerised system in which dealers (via brokers) enter the prices and the quantity they are willing to buy or sell. They can then wait for the market to move to the price they set as their limit. Alternatively, they can instruct brokers to transact immediately at the best price currently available on the order book system. Trades are then executed by the system if there is a match between a buy order price and a sell order price. These prices are displayed anonymously to the entire market. An example of prices and quantities is shown in the lower half of Figure 4.20 – a reproduced SETS screen as seen by brokers.

Figure 4.20 A typical SETS screen

The buy orders are shown on the left and the sell orders on the right. So, we can observe for Lloyds Bank that someone (or more than one person) has entered that they are willing to buy 100,000 shares at a maximum price of 69.92p (bottom line on screen). Someone else has entered that they would like to sell 6,930 shares at a minimum price of 70.53p. Clearly the computer cannot match these two orders and neither of these two investors will be able to trade. They will either have to adjust their limit prices or wait until the market moves in their favour.

As we travel up the screen we observe a closing of the gap between the prices buyers are willing to pay and the offering price of sellers. On the eighth line from the bottom we see that buyers want 36,060 shares at 70.17p whereas sellers are prepared to accept 70.20p for 87,116 shares. Now we are getting much closer to a match. Indeed, if we look above the yellow strip we can see the price where buyers and sellers were last matched – the ‘last traded price’ is 70.18p.

These screens are available to market participants at all times and so they are able to judge where to pitch their price limits. For example, if I was a buyer of 5,000 shares entering the market I would not be inclined to offer more than 70.2p given the current state of supply and demand. However, if I was a seller of 5,000 shares I would recognise that the price offered would not have to fall below 70.17p to attract buyers. If I was a buyer of 110,000 shares rather than just 5,000 I have two options: I could set a maximum price of 70.2p, in which case I would transact for 87,116 immediately but would leave the other 22,884 unfilled order in the market hoping for a general market price decline. Alternatively, I could set my limit at 70.44p, in which case I could transact with those investors prepared to sell at 70.2p, 70.23p, 70.43p and 70.44p. The unfilled orders of the sellers at 70.44p (118,170–110,000) are carried forward on SETS.

To improve trading liquidity on SETS, in 2007 the system was modified so that market makers can now post prices on it. Thus, it offers a continuous order book with automatic execution but also has market makers providing continuous bid and offer prices for many shares (but these trades are executed through the automatic system). Market makers assist with tighter bid–offer spreads, greater transparency of trades and improved liquidity.

The trading system for less liquid shares – SETSqx

For buying and selling less frequently traded shares Stock Exchange Electronic Trading Service – quotes and crosses (SETSqx) trades in Main Market and AIM shares (over 1,000 companies). SETSqx combines order book technology (similar to the SETS method of trading) with quote-driven trading. On SETSqx a single market maker’s quote can be displayed if a market maker is interested in quoting a price. Ideally, the exchange would like many market makers quoting prices so that competition encourages keener prices for share owners. But given these are less frequently traded shares there might only be one or two market makers willing to bear the cost of holding a stock of shares ready for dealing.

An investor or broker wanting to trade with a market maker can do so in the normal way throughout the day (in the same manner as with the SEAQ system), but also can connect to the electronic system and put on to the system’s screen display an order for shares stating a price at which they would like to trade, either to sell or to buy (similar to SETS). This is particularly useful if there are no market makers in that share.

The actual trading on the order book takes place during five auctions each day (at 08.00, 09.00, 11.00, 14.00 and 16.35), in which investors make bids and the system matches up buyers and sellers. In the first few minutes of the auction period traders can put in limit prices for buy or sell orders. They can keep withdrawing them or modifying them, while observing other limit prices, during this period. Then the computer moves to a new phase where it sets the prices at which trades will be automatically completed, informed by the most recent bids – a price permitting the maximum number of trades. Outside the auction times a broker has the option to phone the counterparty behind a named order and fill this before the next auction if terms are agreed.

What happens after dealing?

When a trade has been completed and reported to the exchange it is necessary to clear the trade. That is, the exchange ensures that all reports of the trade are reconciled to make sure all parties are in agreement as to the number of shares traded and the price. The exchange also checks that the buyer and seller have the cash and securities to do the deal. Also the company registrar is notified of the change in ownership. Later the transfer of ownership from seller to buyer needs to take place, which is called settlement.

These days clearing frequently does not just mean checking that the buyer and the seller agree on the terms of the deal. The clearing house also acts as a ‘central counterparty’ which acts as a buyer to every seller and a seller to every buyer. This eliminates the risk of failure to complete a deal by guaranteeing that shares will be delivered against payment and vice versa. Shares on SETS and SETSqx go through those central counterparty organisations approved by the LSE. The London Stock Exchange has now moved to a ‘two-day rolling settlement’ (trading day +2, or T+2), which means that investors normally pay for shares two working days after the transaction date.

In the old days (the 1990s) the transfer of shares involved a tedious paperchase between investors, brokers, company registrars, market makers and the Exchange. The modern system of settlement, called CREST, provides an electronic means of settlement and registration. CREST acts as a central securities depository (CSD) enabling dematerialisation by keeping an electronic register of the shares, a record of shares traded on stock markets and providing an electronic means of settlement and registration.

This system is cheaper and quicker than the old one – ownership is now transferred with a few strokes on a keyboard. Under CREST, shares are usually held in the name of a nominee company rather than in the name of the actual purchaser. Brokers and investment managers set up and run these nominee accounts. Thus, when an investor trades, their broker holds their shares electronically in their (the broker’s) nominee account and arranges settlement through their membership of the CREST system, increasing transaction speed. There might be dozens, hundreds or thousands of investors with shares held by a particular nominee company.

The nominee company appears as the registered owner of the shares as far as the company (say, Sainsbury or BT) is concerned. Despite this, the beneficial owners – that’s you or me – receive all dividends and any sale proceeds.

Some investors oppose the CREST system because under such a system they do not automatically receive annual reports and other documentation, such as an invitation to the annual general meeting. They also potentially lose the right to vote (after all, the company does not know who the beneficial owners are). Investors can insist on remaining outside of CREST. In this way they receive share certificates and are treated as the real owners of the business. This is more expensive when share dealing or simply maintaining an account at a broker (the annual fee rises). There are plans to abolish share certificates in 2023 for new issues and 2025 for existing shares.

Placing shares in a nominee account can remove a lot of the administrative work for investors. For example, if you wish to sell shares held in certificated form (a piece of paper) it is necessary to sign a stock transfer form and send it with the share certificate to your broker, who will then check the form and pass it on to the company registrar. Postal dealing and settlement are clearly impossible within the T+2 settlement time, as well as being more fiddly for brokers. Many brokers allow you to delay settling a deal beyond two days. They may permit T+5, T+10, or even T+20.7 This is subject to special arrangement, and there will be additional administrative costs to pay. So we have a market where some clients, who use the nominee system, will be settled at T+2, while for private investors, who prefer to receive certificates, settlement is more likely to be T+10.

Nominee companies are ring-fenced, so that if the broker goes bust the shares in the nominee company are unaffected. In the event of fraud, investors are guaranteed compensation of up to £85,000 under the Investor Compensation Scheme if they are dealing through a broker authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority (see Chapter 19).

As well as losing the right to automatic receipt of annual reports and other documentation, such as an invitation to the AGM and voting, shareholders with nominee accounts can also miss out on perks, such as a 20 per cent discount voucher to use in Moss Bros (see www.hl.co.uk/shares/shareholder-perks for a list of perks). These may not be automatic but, with the standard nominee service offered by brokers, investors can request that reports and accounts, perks and invitations to company meetings be passed on. Brokers may also communicate votes on company matters to AGMs. Investors may be charged extra for these services, but most are free.

If I request it (by email), Charles Stanley quickly and efficiently tells companies that I will be attending their AGM. The broker sends me a form a few days before the meeting stating that I will be acting as proxy for the broker’s nominee company, Rock Holdings. I can send this to the company to register my votes. Alternatively, I can vote at the meeting given that Charles Stanley warned them I’ll be turning up. Charles Stanley provides this service free. It is similar with my online accounts. I made sure before I opened them that they had a system allowing me to vote. I do like to go to AGMs and ask the directors probing questions – and most of them welcome the interest.

There is a compromise position between nominee-held shares and certificates: personal membership of CREST (also called sponsored membership). The investor is then both the legal owner via CREST and the beneficial owner of the shares, and also benefits from rapid (and cheap) electronic share settlement.8 The owner will be sent all company communications and retain voting rights. However, this can be more expensive than the nominee CREST accounts run by brokers. Personal CREST account costs vary from broker to broker. Some do not charge, while others ask for £300 per year or more. Some brokers make an extra charge (say £10) for each trade through a personal CREST. These days, few brokers offer CREST personal accounts.

Article 4.2 criticises nominee accounts. Note the additional disadvantage: transferring your holdings from one nominee account to that at another broker can cost hundreds of pounds.

Article 4.2 - Put the equality back into equities

The UK’s undemocratic nominee system needs an overhaul

By John Hughman

One issue that has dominated my inbox is the shortcomings of the UK’s nominee account structure. I must admit that, until I took the hot seat and the letters started to arrive, I had barely paid it a second thought. But as more angry emails rolled in, it became clear to me just how undemocratic the nominee system is. In fact, I’ll go further — it is an indefensible embarrassment to a country that claims to be one of the fairest and most financially advanced in the world. I too am angry now.

In short, if you want to buy shares without breaking the bank you have to use a nominee account. If you want to deal quickly, or take advantage of the tax breaks on offer in Isas and Sipps, you will need to use a nominee account. Yet once you have parted with your cash and dealing costs, you will still not, under UK company law, be recognised as the nominal owner; in fact, the company you’ve invested in will have no idea who you are.

Some estimate that private shareholders could hold as much as 30 per cent of UK equities — but no one really knows, because only the names of the nominee providers, which pool thousands of individual holdings, appear on the register.

It gets worse. You have no automatic right to receive information such as annual reports, attend AGMs or vote on important issues such as executive pay. You will often rely on the discretion of your broker to be offered these, and in some cases the broker may try to charge for providing this “privilege”.

If you want to use a different broker, you will have to pay to transfer your holdings — effectively locking you in even if you’re getting a bad service. In this respect, it is brokers and not shareholders who benefit most — a high price to pay for the apparent convenience of being able to administer all of your shares in one place.

Alternatives exist, but these are becoming an ever-more endangered species. Paper certificates will, in a matter of years, be phased out under dematerialisation plans to be enshrined in European law — and so far there is no sign of a named electronic register to replace them. The current electronic equivalent of certificates, personal Crest services, are becoming ever scarcer.

Some brokers have hiked their Crest prices to absurd levels, presumably to discourage clients from using the service. Others are scrapping them altogether — only this week Alliance Trust Savings announced that following its takeover of Stocktrade, it is to withdraw Personal Crest Services; clients will need to switch to archaic paper certificates or nominee accounts instead — hardly comparable alternatives.

Brokers say it doesn’t matter, that the nominee structure is good enough, because very few shareholders want to vote or receive the annual reports anyway. This is a chicken and egg argument — advocates of change argue that engagement is low precisely because of obstacles put in the way by the nominee system. Better brokers — such as Killik or the Share Centre — offer full information and voting rights to their nominee account holders. But neither answer really gets to the nub of the issue, which is that although the nominee system works much of the time, it does occasionally let shareholders down.

In the past, brokers have gone bust, leaving shareholders chasing the regulator to compensate them — and then only for a maximum of £50,000, well below the $1m protection offered in the US.

Organisations such as the UK Shareholder Association and Sharesoc have tirelessly campaigned for years for a single electronic register per company, recognising every individual owner, accessible to every broker.

They have frequently been met, so I am told, with resistance from those with the power to change the system — or complaints that introducing such a system would be prohibitively expensive.

Yet the idea is hardly at the cutting edge of information technology. Already in place in most developed markets, electronic registers are, ironically, exactly what the UK government advocates emerging markets seeking to establish an equity culture should adopt. And when paper certificates are scrapped, it is the only alternative that does not require the forcible removal of full shareholder rights from millions of Britain’s more engaged investors. The government has often spoken about encouraging wider participation in financial services. But if they are serious about creating a more financially engaged society, a good place to start would at the very least be to fix the nominee system to give private shareholders the full rights they deserve.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 28 August 2015

© The Financial Times Limited 2015. All Rights Reserved.

If you are thinking of opting for a nominee service you might like to ask the following:

- What charges will be levied for what services?

- How will the investments be protected while in the nominee account?

- Will I receive annual reports and accounts, the right to vote, invitations to AGMs and EGMs and perks?

Paying for your shares

There are a number of different ways to pay for your shares:

- Open a deposit account with the broker or bank. Your broker is able to draw money from the account on your behalf at any time to settle deals.

- Send a cheque in the post. Your broker may not be willing to buy for you until the cheque is cleared, especially if you have a two-day deadline for settlement.

- Visit a high street broker and pay there and then, for example, by credit card.

- Pay by debit card over the telephone.

Internet dealing

The majority of execution-only share trades are conducted online. While online trading is low cost, there are still some problems:

- Some systems are crash-prone. Computer failure can be very frustrating, so always have a back-up method of trading. It might be worth opening accounts at two or more brokers.

- The security of information in cyberspace is a worry for many people, although encryption technology is helping the situation.

- Internet dealing usually requires the use of a nominee account.

- The simplicity and speed of trading may lead investors to trade too frequently or to make reckless trades – many day traders lose a fortune in transaction costs.

- Watch out for silly mistakes resulting in purchase of the wrong number of shares by punching on the wrong key.

Direct market access

Direct market access (DMA) systems allow private investors to trade directly in the stock market, placing buy and sell orders into the LSE’s electronic order books alongside the professionals. To do this you need to download the necessary software from a DMA provider – a service offered by some stockbrokers. Despite the direct link into the market you will still be trading via a broker when using DMA.

To use DMA you will subscribe for a Level 2 package (see earlier) so that you can see the buy and sell orders placed by other investors, and then be able to watch your order flash up on the SETS or SETSqx screen.

With ordinary online dealing your broker’s system seeks out the best price from several RSPs. However, this may not be the best price possible. There are several advantages in inputting your own buy and sell prices:

- Better prices and a greater chance of execution: Say you want to sell shares in a company and observe a quoted spread of 200p–202p (the lowest price sellers are willing to accept is 202p and the highest price a buyer is willing to pay is 200p). A non-DMA trader could expect to get 200p, but a DMA trader might place a limit order of say 201.5p to entice a deal. Being able to see everyone else’s buy and sell orders including the amounts on offer allows you to get a feel of the balance of supply and demand, which helps in selecting where to pitch your price.

- Speed: Your order goes into the system in a fraction of a second after you press your keyboard button and may be completed immediately. Also you can trade on breaking news. For example, other traders may have left sell orders on the SETS system. When positive news is announced for a company (a big contract win) these other investors may be slow in changing their prices. If you have DMA and spot the news early enough you might bag a bargain.

- Testing and adjusting prices: You will be able to see where your order lies on the LSE’s order book and how close you are to getting it filled. This allows you to adjust the price if you wish to find a counterparty and trade immediately.

The cost of a DMA service varies tremendously. Furthermore, the sector is evolving, as brokers supplying the software and access arrangements compete vigorously with each other. For infrequent traders the software and Level 2 data can cost hundreds of pounds per year, but if you trade, say, 15 times or more in a month these costs might be waived. Much depends on the special offers available at brokers. DMA is really only suitable for frequent traders (at least five times per week) who have the time to watch markets for hours on end.

Another problem with DMA is the danger of hitting the wrong button – ‘fat-finger trades’. Investors have been known to buy instead of sell (or vice versa), or to trade ten times the amount they meant to, or to accidentally put in a silly price, for example, selling a share at a fraction of its true value.

Not everyone is able to obtain DMA because brokers vet clients to ensure they have sufficient knowledge to trade in this way.

Transferring shares without brokers

It is possible to complete an off-market transfer without the use of a broker if the transfer is between people you know, such as friends or spouses. You need to complete a stock transfer form, which is available free from the company registrar, or from brokers, banks or on the internet9 (legal stationers will charge you for the form). The transfer form on the back of share certificates is for use when you are trading in the stock market, so is not suitable for DIY share selling or gifting. You need to have a share certificate to complete a transaction without a broker. If the shares are held in a broker’s CREST nominee account the broker will charge for the transfer. Stamp duty does not apply to transfers between spouses or gift transfers. For other Main Market company transfers the completed form is sent to Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs Stamp Office with a cheque for stamp duty of 0.5 per cent. The stamp office will return the form (after stamping it) for you to send to the registrar of the company who will issue a new certificate.

Useful websites

| www.advfn.com | ADVFN |

| www.ii.co.uk | Interactive Investor |

| www.fca.org.uk | Financial Conduct Authority |

| www.londonstockexchange.com | London Stock Exchange |

| www.euroclear.com | CREST |

| www.pimfa.co.uk | Personal Investment Management and Financial Advice Association |

_______________

1 I am very grateful to Riccardo Landucci at Canaccord Genuity who kindly read this chapter and made valuable suggestions for improvement.

2 There is a problem in compiling and comparing statistics on performance because what the service brokers provide is specific to the particular needs of the clients. For example, is the client risk-averse? How diverse is their general portfolio, i.e. how much investment do they have outside of shares?

3 If you would like to know more about investment philosophies you might like to read my Deep Value Shares newsletters on ADVFN or one of my books Great Investors (Financial Times Prentice Hall, 2011) or The Financial Times Guide to Value Investing (Financial Times Prentice Hall, 2009), The Deals of Warren Buffett, Vol 1 (Harriman House, 2017), or The Deals of Warren Buffett Vol 2. (Harriman House, 2019).

4 If you are dealing online instead of speaking to a broker, you will call up the broker’s website using your user ID and password. You will then input the name of the company or its code and view the prices (a simple summary of current prices if you are on a Level 1 system, or a display of a range of dealers’ prices if you are on Level 2).

5 The stockbroker is allowed to complete the deal ‘in-house’ by taking on the deal himself if he can match the best prices offered by the market makers.

6 Market makers are permitted to delay reporting very large orders for a few hours, or even days, to allow them to unwind very large positions.

7 To deal beyond T+2 you may have to pay additional sums to market makers.

8 The broker still acts as sponsor, even though the accounts are held in the shareholder’s name.

9 Make sure you download the UK version.