Tricks of the accounting trade

Financial statements are supposed to show the underlying economic performance of a company. The profit and loss account shows the difference between total revenue and total expenses. The balance sheet displays the assets, liabilities and capital of the business at a snapshot moment. What could be simpler than adding a few numbers to get a trustworthy and definitive conclusion?

Well, drawing up a set of accounts is far from simple, or unambiguously precise. It is nowhere near as scientific and objective as some people would have you believe. There is plenty of scope for judgement, guesswork or even cynical manipulation. Despite the mountain of accounting rules and regulations there are numerous opportunities to flatter the figures, or at least to offer two or three legitimate estimates of the value of something or the profit generated by an activity.

Imagine the difficulty facing the company accountant and auditors of a clothes retailer when trying to value a dress which has been on sale for six months. Let us suppose the dress cost the firm £50. Perhaps this should go into the balance sheet and the profit and loss account would not be affected. But what if the store manager says that they can only sell the dress if it is reduced to £30, and contradicting them the managing director says that if a little more effort was made £40 could be achieved? Which figure is the person who drafts the accounts going to take? Profits can vary significantly, depending on a multitude of small judgements like this.

Consider another simple example. Suppose that there are two identical companies except that during the last year one bought a £10 million factory, while the other spent £10 million on advertising. How are you going to value the assets at the end of the year? The company that acquired the £10 million factory has something tangible to show. Perhaps we should say the year-end value of the asset is £10 million. On the other hand, you may think the asset has decreased in value since it was purchased. Perhaps it should now be valued at only £9 million. So what do you do with the £1 million write-off? Should that be regarded as a cost of doing business and deducted from profit? Or, if the £1 million reduction in value is due to a general downturn in property values, is it best to account for it by stating a separate exceptional charge?

The second firm’s accounts are even more subject to judgement. Presumably the management believed that expenditure on advertising would create something of value – an enhanced brand, for example. This asset may be more valuable than the physical assets bought by the first company, and yet, because intangibles are usually valued at zero, the entire expenditure becomes a cost for the year, reducing the profit significantly.

Given that accounts are malleable, investors need to be alive to three possibilities:

- Directors and accountants are trying hard to present a picture of the firm’s performance and financial standing that is true and fair but are forced to make numerous judgements along the way. They are trying to apply the rules to produce accurate figures. However, if another equally honest and meticulous accountant were making the judgements the figures would look different simply because some of these judgement calls are finely balanced. We do not live in a mathematically precise world – the investor needs to accept that the accounts merely provide no more than ballpark figures. Having said this, for most firms, with accountants conscientiously trying to avoid tipping the balance either way between favourable and unfavourable reporting, the room for judgement should not make more than about 10–20 per cent difference.

- The second possibility is creative accounting, in which the letter of the accounting standards is abided by, but there is a deliberate attempt to flatter the figures. When judgement calls are required there is a bias to show a favourable figure. The accounting regulators periodically try to close loopholes to bring accounts back to a true and fair view, but many managers and their accountants are adept at outwitting the rule setters. Every now and again there is the deafening sound of stable doors being slammed long after the horses have bolted.

- Fraud occasionally occurs in which the rules are completely flouted. World-Com is probably a record holder for both the amount involved and for its brass-necked boldness in committing such a simple fraud. All it did was declare that $3.8 billion of operating expenses were not expenses at all and claimed that this money went to create assets of ongoing value to the company. Annual profits were artificially boosted by nearly $4 billion. Over in Spain the boss of Gowex, a WiFi provider, admitted he had falsified its accounts in 2014. He said “I made a voluntary confession in court. I will face the consequences. I am deeply sorry.” As much as 90% of its supposed revenues did not exist – it managed far fewer WiFi spots than claimed. The story of the Gem of Tanzania is an interesting case where the directors claimed a stone was worth £11 million, thus bolstering a balance sheet of an otherwise very shaky company – see Article 13.1. The gem was eventually sold for £8,000 and three Wrekin directors, including Mr Unwin, were disqualified from holding such positions.

Article 13.1 - Now £11m Gem of Tanzania hits rock bottom

By Jonathan Guthrie

One of the strangest tales in the history of company accounting looks increasingly likely to end with a fabled gem being downgraded to an unusual paper weight.

The Gem of Tanzania, a large ruby whose £11m valuation once underpinned the finances of a failed company with yearly turnover of £103m, may be worth as little as £100.

Rebuffed by large auction houses, administrators to Wrekin Construction, a Shropshire building company, are now planning to advertise the big purple rock in a small magazine whose subjects include New Age crystals.

The police said yesterday that they were considering whether to mount a fraud investigation, while forensic accountants are already on the case.

After Wrekin collapsed in May it emerged that the main asset of the business was an £11m ruby. Derbyshire businessman David Unwin used the jewel, previously valued at £300,000, to revive the balance sheet of Wrekin, which he bought in 2007.

A Financial Times investigation found that the gem was sold to a South African-born businessman for the equivalent of £13,000 in Tanzania in 2002. The jewel was then handled by at least one other intermediary before Mr Unwin bought it through a land deal.

Two key valuation documents acquired by Mr Unwin with the gem were denounced as forgeries by the purported valuers. Mr Unwin has consistently said that he is innocent of any wrongdoing. Supporters say that he would be the victim of any fraud.

It is understood that prestigious London auction houses rejected the gem because its value was too low.

Marcus McCallum, a Hatton Garden gem dealer said: “The Gem of Tanzania may not be worth the cost of the advertisement. A two-kilogram lump of anyolite [a low-grade form of ruby] is probably worth about £100. A valuation of £11m would be utterly bonkers.”

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 1 October 2009.

© The Financial Times Limited 2009. All Rights Reserved.

What you learn here cannot protect you against out-and-out fraud, but it can explain a number of areas of accounting in which judgement calls have to be made and where there is sufficient lack of clarity in the rules for a potential bias to creep in and open up the possibility of producing artificially increasing profits, or higher asset levels than are truly warranted. After reading this you should understand the high degree of flexibility in accounting data and the potential for enhancing companies’ reported performance through circumventions of the spirit of the accounting regulations. You will view accounts with a questioning mind and make sure you are aware of the company’s accounting policies and the implications behind them. Remember: if it looks too good to be true, then it probably is.

Goodwill

When one company acquires another there is usually a difference between the fair value of the assets acquired and the price paid. The difference is termed Goodwill An accounting term for the difference between the amou . The significance of this is best explained through an example. Imagine that Stephenson Brunel Ltd has been operating for 50 years and is making profits of £20 million per year. The assets on its balance sheet have a stated fair value1 of £100 million after subtracting all liabilities (£100 million represents the net assets).

You and I are owners of a railway company in another part of the country and we decide to offer £220 million to buy all the shares in Stephenson Brunel. Our offer price is based primarily on the earnings potential of the business, not on its net assets. The offer is accepted. We have paid £120 million above the net asset value. This is motivated by our high regard for the company’s economic franchise – for example, it has a near monopoly position (economic franchises are discussed in Chapter 15).

Stephenson Brunel now becomes a subsidiary of our company, and consolidated accounts are prepared. But how do we draw up a balance sheet? Prior to the acquisition we held £220 million in cash as one of our assets in the balance sheet. We exchanged this for £100 million of net assets. There is a gap of £120 million. To solve this problem the accountant places in the balance sheet a £120 million asset called ‘goodwill’. Now the books will balance: £220 million buys £100 million of tangible assets plus £120 million of the intangible asset called goodwill.

What happens next can make a huge difference to the balance sheet, the profit and loss account and to various measures of performance. In the UK, until 1998 companies were permitted to write off purchased goodwill through the balance sheet. Immediately goodwill seemed to simply vanish from the accounts.2 Managers liked this approach for two reasons. First, because profits in the year of acquisition and all future profits do not have to suffer the burden of an annual expense of writing off a portion of the goodwill through the profit and loss accounts year by year. It was all written off in one year – moreover, it was written off via the balance sheet, so the profits did not take a hit. Second, reducing the net assets of the firm by £120 million makes managers look good when they are judged by a return-on-capital measure, such as return on capital employed. The denominator (capital) is reduced while the numerator (profit) does not suffer. Managers begin to look like geniuses because they appear to be making high profits on a lower capital base.

Accountants pondered these distortions and concluded that, generally, acquired goodwill does in fact decline in value over time, and so needs to be amortised (depreciated) in a similar fashion to tangible assets, such as machinery. It should not be assigned a zero value in the year of acquisition. Between 1998 and 2005 the rule was that purchased goodwill should be capitalised (placed in the balance sheet at its purchase value) and then amortised over the asset’s useful economic life, up to a maximum of 20 years in most cases.

Now imagine you are a director needing to show good profit figures and you know that £120 million of purchased goodwill has to be apportioned as an expense to the profit and loss account over ‘its useful economic life’. You can see there is considerable room for debate on the length of time representing this asset’s useful economic life. Would you tend to plump for a write-off over, say, six years, so that £20 million comes off your profit in each of the next six years? Or would you go for the longest period possible, 20 years, in which case only £6 million is amortised each year? Well now, guess what the vast majority of firms ‘estimated’ the length of ‘useful economic life’ to be. Yes, it’s 20 years. Did this reflect reality in terms of the true value of the intangible assets over time? I doubt it. Obsolescence, competitor action and changes in the market environment can have a devastating impact, and many firms lose their business franchises in as little as two or three years.

Also, under these rules, companies can amortise over more than 20 years, or even not amortise at all, if they could show that the balance sheet entry showed a reasonable valuation. (However, if they chose either of these methods the assets must be reviewed each year to see if it is being impaired.) If it was impaired then the goodwill was written down in the balance sheet and the loss shown separately in the profit and loss account (as a goodwill impairment charge). This is all very reasonable. The problem is that the numbers used were based on estimates and forecasts made by the company. Many firms claimed values for purchased goodwill that you or I might question.

Since 2005 International Financial Reporting Standards have applied to the consolidated accounts of listed companies on LSE’s Main Market. They now also apply to AIM companies. Under these rules there is a prohibition against the systematic annual amortisation of goodwill. Thus ‘purchased’ goodwill (from an acquisition) is included under ‘Intangible non-current assets’ or ‘Goodwill and other intangible assets’ at its initial cost. However, this figure must be reviewed at least annually thereafter, to see if the value has been impaired. If there is no impairment then the goodwill remains at its cost figure. With impairment the figure is written down to the lower amount in the balance sheet. Furthermore, an impairment charge is a negative element in that year’s profit and loss account, thus depressing reported profits.

Carillion’s managers avoided goodwill impairment and thereby kept reporting profits and paying dividends, until it all collapsed.

Article 13.2 - Carillion’s troubles were shrouded in a fog of goodwill

By Jonathan Ford

In March 2011, just as Britain’s new coalition government was preparing to dramatically cut back on public spending, Carillion paid £306m to buy a company that helped consumers to take advantage of government-funded energy schemes. Eaga was a contractor for public programmes promoting energy efficiency among the less well off.

Eaga may seem a footnote in the wider drama of Carillion’s collapse. The group was ultimately buried by a whopping £1.2bn landslide of contractual writedowns in mid-2017, most relating to its Middle Eastern construction activities.

But the energy services subsidiary is central to some of the key accounting questions that continue to swirl around Carillion following its decision to file for insolvency six months ago. These come at a time of rising concern about the weakening of accounting standards on both sides of the Atlantic, and how they enable companies to push out over-optimistic versions of their figures.

Carillion may have collapsed after restatements of contractual earnings erased six years of profits. But some believe its accounts were already straining at the boundaries of reality. And at the heart of these concerns lies the Eaga acquisition itself.

As with many acquisitive service businesses, Carillion had few tangible assets on its balance sheet; items such as property or plant that were marketable and could easily be valued or sold off.

Instead the company’s books were stuffed with intangibles — not least the goodwill on its many deals. On Eaga, it wrote up £329m of goodwill, or more than 100 per cent of the purchase price. That was a big chunk of the £1.6bn in goodwill it accumulated in its accounts by 2016 — equivalent to 35 per cent of Carillion’s total assets.

In the five years before 2017, the group impaired not a penny of its goodwill pile, despite growing circumstantial evidence that some of those assets might have slumped in value.

Its avoidance of impairments was one of the reasons Carillion could continue paying dividends (and bonuses to managers). In 2016, despite the looming disaster, it paid a record dividend of £78m.

There is the question of whether goodwill has much status as an asset. It cannot be sold and, in the event of bankruptcy, almost certainly has no value. Companies still amortise other intangibles such as software and customer lists because of their uncertain value.

“Not surprisingly, a CEO who overpays in an [acquisition] is not particularly keen to publicly acknowledge that overpayment, so instances of firms declaring their goodwill as impaired are rare,” Prof Ramanna [Oxford university’s Blavatnik School of Government] says. He cites the reluctance of US banks to write down purchased goodwill even after the financial crisis. Of the 50 largest American financial institutions, only 15 wrote down any goodwill in 2008, although nearly 40 of them were trading well below book value at the time.

Carillion’s bosses appear to have shown a similar reticence. Almost from the moment of its purchase, Eaga faced a remorseless government squeeze on spending. In the first year, the newly renamed Carillion Energy Services recorded a 20 per cent decline in annualised turnover, and a loss to the tune of £113m, as it attempted to rationalise its shrinking business. Sales continued to slump in subsequent years.

Had Carillion impaired Eaga, the board might not have been able to pay the group’s two top executives, Richard Howson and Richard Adam, £1.8m in bonuses in the two years before the company’s failure. “And that’s before you get to its impact on things like dividend paying capacity, potential creditworthiness or even solvency,” Ms Landell-Mills [head of stewardship Sarasin and Partners] adds.

By 2015, accumulated goodwill was the one thing standing between Carillion and a brewing crisis. As the group’s bosses pondered but deferred an equity raising to cut its increasingly burdensome debts, they were determined to keep paying dividends.

Under UK law, companies can only make distributions if they have sufficient “distributable reserves” — or accumulated and realised profits — to do so. In its 2015 figures, Carillion had £373m of shareholders’ funds (a rough proxy for distributable reserves) on its parent company balance sheet, out of which it paid a dividend of £77m. Impairing goodwill means writing down the carrying value of a subsidiary and hence reduces shareholders’ funds — and the distributable reserves the parent company has available.

Had Carillion then written down all the goodwill on Eaga, it would not have had sufficient reserves to pay that full dividend: the maximum would have been £44m. “Cutting the dividend at that point because there weren’t the distributable reserves to pay it would have been a big red flag for investors,” says one analyst.

In 2016, the group had just £317m of shareholders’ funds left. Under any circumstances, after making such a writedown, it could not have issued any dividend, yet it paid out the record £78m. “If there is one good thing to come out of Carillion, it’s that it offers a salutary reminder about why preventing overstatement matters,” says Ms Landell-Mills.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 18 June 2018.

© The Financial Times Limited 2018. All Rights Reserved.

Directors are getting quite adept at encouraging shareholders to focus on ‘underlying’ profits that exclude these charges. The reality is that it is very difficult to know, in most cases, when goodwill has declined in value and by how much. There remains great latitude for the employment of ‘judgement’ here, so we will have lots of fun and games over the next few years as companies avoid write-downs.

All the discussion so far applies to purchased (‘acquired’) goodwill. What about goodwill that is generated internally? Most company’s shares are worth a lot more than the net assets total shown in the balance sheet. The stock market values a company on the basis of its future earnings, which, in turn, come from all its ‘assets’, including those not measured in a balance sheet, such as extraordinarily good reputations or strong relationships with customers. This internally generated goodwill cannot be shown in the accounts – any figure selected would be too subjective. Stock market investors are left to value this on their own.

There are, however, some intangible assets that can be valued on the balance sheet. These are intangibles for which it is possible to get a reasonably firm grasp on the cost of creating or buying them. For example, while most research and development (R&D) expenditure is written off in the year in which it occurs (the profit figure is reduced), it is possible for a UK company to argue that the development expense is for a separately identifiable project for which there is reasonable expectation of specific commercial success. In this case the expenditure can be capitalised, that is, shown as an asset on the balance sheet, and then the expense to the income statement (amortisation of the asset) is spread out over many years.

Copyrights, licences (such as bookmakers’ licence to operate), patents and trademarks may also be capitalised and amortised over their useful lives.3 With all of these intangibles there is considerable room for disagreement about appropriate values over time and the amount that should be deducted from the income statement each year.

Points to watch out for when viewing goodwill and other intangibles in accounts include the following:

- Amortisation generally takes place by an arbitrary amount over an arbitrary time period. However, as a safeguard, the policy adopted must be clearly stated in the accounts.

- Goodwill and other intangibles are frequently not depreciating assets in the everyday sense of really losing value. When analysing a company it might be advisable to add back the amount of amortisation to the year’s income statement to obtain a measure of normalised earnings. You could also add back goodwill accumulated over many years to obtain a more realistic net asset figure.

- In some companies goodwill and other intangibles may be eroding much faster than the amortised rate. The analyst will need to reduce the profit and balance sheet asset figures to account for this.

- A company showing significant regular goodwill impairment charges should be viewed with scepticism. This may indicate that the company has a habit of overpaying for acquisitions.

All the above adjustments by the analyst are, of course, subjective and imprecise, but are nevertheless better than simply ignoring the issue. The adjustments can have profound effects on key measures such as net assets, gearing, earnings per share and return on capital employed.

Fair value

When a company is acquired its assets are revalued at fair value on the acquisition date for the purposes of consolidation in the group accounts. Also under International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) companies have to value certain assets at fair value whether or not they were acquired through acquisition.

In the Stephenson Brunel example we assumed that the fair value of net assets was £100 million (which for the sake of simplicity is the same as the stated value in Stephenson Brunel’s balance sheet). This left £120 million of goodwill. Given the scope for discretion in this area it might be possible for the directors to argue that the assets are in fact worth only £50 million. Auditors might then agree, and £50 million is placed in the consolidated balance sheet. Goodwill in the balance sheet therefore rises to £170 million (£220m – £50m). Perhaps you may say that the directors have acted prudently and made sensible provision for the potential of asset devaluation. But what if next year these assets are sold for £180 million? Well, income gets a boost of £130 million because of the ‘profit’ on the difference between the ‘fair’ value of the assets (£50 million) and the sale proceeds (£180 million).

Thus, profits can be massaged by marking down fair values of acquired assets. There are also (dubious) benefits prior to selling the assets: depreciation is lower and so less is coming off the profit figure each year; undervaluing stock items reduces future cost of sales to enhance profits; and undervaluing receivables will help a later year’s operating profit if customers eventually pay more than the stated amount owed.

Under the IFRS fair value accounting has become a major area of controversy.

Article 13.3 - The big flaw: auditing in crisis

By Jonathan Ford and Madison Marriage

Fair value accounting had been firmly shunned by the US Securities and Exchange Commission for contributing to the losses of the 1929 crash. Yet contemporary events gave the hypothesis respectability. Soaring inflation in the 1970s made historical cost balance sheets seem misleadingly out of whack with property values, leading to asset stripping. America’s savings and loan crisis in the 1980s was partly blamed on these institutions having out-of-date books.

From the 1990s, fair values started to supplant historical cost numbers in the balance sheet, first in the US and then, with the advent of IFRS accounting standards in 2005, across the EU. Banking assets held for trading started to be reassessed regularly at market valuations. Contracts were increasingly valued as discounted streams of income, stretching seamlessly into the future.

This was also a time when managers’ pay, especially in the US, was rising through the use of market-linked incentives. Between 1992 and 2014, equity-based pay at S&P 500 firms rose from 25 to 60 per cent of their total remuneration, according to database ExecuComp.

It did not take long for bosses to perceive the pecuniary possibilities of their ability to influence fair values. Between 1995 and 1999, for instance, Enron’s stock underperformed the S&P 500 index. Yet in 2000, when the US energy company’s accounting chicanery started to kick in, its shares wildly outperformed the benchmark. In the 10 months before its collapse, the company paid out $340m to executives.

“The problem with fair value accounting is that it’s very hard to differentiate between mark-to-market, mark-to-model and mark-to-myth,” says one investor who is on the board of an audit firm. In theory, fair value should not preclude sound audits. But it does make it harder. The greater latitude given to bonus-hungry management by looser evidential standards increases the pressure on auditors.

Ms Landell-Mills [head of stewardship Sarasin and Partners] worries that investors have not absorbed the consequences for the public interest. “In the extreme,“ she says, “fair value accounting that treats upward revaluations as legitimate profits, and ignores future foreseeable losses, can facilitate Ponzi schemes where more and more illusory profits permit executives and existing shareholders to extract cash through bonuses and dividends. It won’t be long before you come unstuck.”

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 1 August 2018

© The Financial Times Limited 2018. All Rights Reserved.

The IFRS insists that property held by a company as an investment (not for use in manufacturing or commercial process) can be accounted for in either of two ways. First, the balance sheet value is altered to market value and changes in fair value from one year to the next are added to, or deducted from, the income statement. Thus, a company can make a normal operating profit in its manufacturing division or by renting out houses, of say £30 million, but this can be drowned in the reported earnings figure by a massive write-down on the fair value of its properties, say £240 million.

Companies can report very large losses because of this fair valuation of property assets. The alternative accounting approach permitted is to state investment properties at cost in the balance sheet and depreciate over the useful life. You can imagine that in a property crash many companies would like to follow the second approach. However, the rules are fairly strict on what can be reported under each approach – but that doesn’t prevent some flexibility on the determination of a fair valuation.

Another problem arises with the valuation of financial instruments held by non-financial firms. Some are held in the balance sheet at their amortised cost, whereas others are revalued at fair value with the change in value going through the balance sheet. Yet others are revalued at fair value with the change in value going through the balance sheet and the income statement. The rules governing these classifications is complex and, as you can imagine, open to much interpretation and judgement.

What was our revenue again?

The basic rules of revenue recognition are that it is recognised in the period when the substantial risks and rewards of ownership are transferred and the amount of revenue can be measured reliably.

The trick of bringing forward revenue from future years into this year is an old one. Sales are not easy to define. Do you recognise sales revenue when the order is placed, when you receive cash from the customer, or when the goods or services are delivered to the customer? For a retailer the issue of revenue recognition is usually simple: a sale takes place when the goods are handed over and payment is received. But revenue is more difficult to allocate to particular years when the revenue bridges different years. For example, imagine a long-term contract to build and service a power station. The order is placed in 2021, construction begins in 2022, the first payments are received in 2023 and ongoing annual service activity is expected from 2024. What revenues do you allocate to each year?

Examples of revenue recognition difficulty are shown below.

Box 13.1 - When to recognise a sale?

- Tesco’s suppliers charge it for goods sent to its store – all boringly normal. But if Tesco sells above a pre-agreed quantity it will get ‘income’ from its supplier – a bonus pat on the back if you like. Until 2014 it also received income in the form of suppliers paying Tesco to make special offers in the stores and grant them the best spots. In 2014 there was a £250m scandal when it was revealed that Tesco had accounted for supplier payments which they anticipated but which did not materialise. In the event, Tesco didn’t reach enough of the thresholds to earn all the ‘rebates’ it had taken as income. When discovered it was forced to restate its accounts, and it was in deep water with the regulators.

- Rolls-Royce was compelled by new accounting rules to change the way it recognised sales. It is normal with jet engines to sell many of them at a loss, but to also sign up the customer to lucrative long-term maintenance contracts. Until 2018 RR was in the habit of bringing forward profits from after-sales service contracts into the year of sale of the physical item. Under new accounting rules the company can now only recognise income in the year the maintenance work is done (most significantly an engine overhaul after five to seven years). In some cases, this meant an engine wouldn’t turn in a profit for five years. After that it would produce good maintenance contract profits. With the new rule RR reported near-term sales and profits fell drastically (by around £700m–£1bn).

- Zero-interest credit cards, where you pay say 2% now to obtain £10,000 for 12 months with no interest charged in that period, present a conundrum for accountants. The credit card companies offer this deal to thousands of people assuming that a proportion will break the rules surrounded the interest free element during the 12 months, thereby causing high interest rates to kick in. Also, the banks issuing the cards expect that a proportion will maintain a high outstanding balance – paying high interest – after the interest-free period. Many banks adopted accounting policies in which they recognised the interest revenue up front based on their estimates of the proportion of customers failing to repay when they were supposed to. This often meant putting revenue into year 1 (and reporting income based on that to investors) when, in fact, the interest won’t actually be charged to the customer until year 2 or 3.

- If you run a website that connects professionals such as lawyers to businesses and you charge 20% of the amount the lawyer subsequently gets from project-working for the business, should you put down 100% of the money received by the lawyer as your revenue? An Exeter-based company, Blur, thought it was OK to put down the total value of projects submitted to its online market place, rather than the 20% arrangement fee. The Financial Reporting Council slapped it down.

- Wiggins, the commercial property developer, recognised a sale of a property once it obtained planning permission satisfactory to the purchaser (without the planning permission the purchaser could back away). But it was forced to restate the accounts because the sale had not yet been completed – it was completed the next year.

- Healthcare Locums was forced to change its accounting policy of recognising revenue generated when it placed medical staff at, say, a hospital, from the date of acceptance of the position to the date at which they actually started.

- Allied Carpets got into trouble for booking sales as soon as an order had been placed (‘pre-despatching’). When this ‘error’ was corrected the accountants found an overstatement of £6.4 million.

- Several companies have included revenue in full in the year of receipt, even though some of the revenue related to provision of services after the balance sheet date. For example, with extended warrantees some retailers have taken full credit for revenue from extended warranties in the period in which the sale of the product took place rather than spreading it over the lifetime of the cover. The rules have been tightened so that the revenue should be recognised over the term of the contract (the excess of the money received over the revenue recognised for the first period’s P&L should be included in payables as a payment in advance and then this is released as performance takes place).

- A company sells software to a customer and in addition receives payment of £12,000 in relation to a maintenance and support contract covering a period of 12 months. Five months of the period covered falls in the supplier’s current year and seven months in the following year. In the past the supplier would take £12,000 credit in the current period. Under new UK rules, the income is spread over the period of the contract (only £5,000 in the current period). The balance sheet will show a £7,000 prepayment.

When there is doubt about the veracity of the figures, the analyst will want to look at cash flow to see when the cash from sales actually turns up. Also carefully read the notes to the accounts to figure out their revenue recognition policy.

Out-and-out fraud on revenue

Examples of out-and-out fraud include the following:

- Telecommunication companies sold useless fibre-optic capacity to each other in order to generate revenues on their income statements (Global Crossing).

- Then there is ‘channel stuffing’ (or ‘trade loading’). A company floods the market with more products than its distributors can sell, artificially boosting sales. A few years ago SSL (condom maker) shifted £60 million in excess inventories on to trade customers.

- Another is ‘round tripping’ (or ‘in-and-out trading’). Two or more traders buy and sell, say, energy contracts among themselves for the same price at the same time. This was one of Enron’s tricks – it inflated trading volumes which makes the participants appear to be doing more business than they really are. Sales revenue growth is often taken by investors as an important yardstick and can affect the value they place on the business.

Exceptional items

When companies issue press releases about their results they tend to emphasise ‘profit before exceptional items’. This is, profit that does not take account of items which are the result of ordinary activities but are large and unusual, such as a large bad debt, windfall profits, merger bid defence costs or losses on the disposal of a subsidiary. Companies are obliged to report both profit before and after deduction of exceptionals. It makes some sense to exclude unusual events so that the underlying trend can be seen. However, directors tend to want to direct your attention to the figure that puts them in the best light. Profit figures feed through to reported earnings per share and if directors can get investors to focus on the ‘sustainable’, ‘maintainable’, ‘core’ or ‘normalised’ earnings which exclude exceptionals then the share price might increase.

There is also the problem of defining what is an exceptional occurrence. It is funny how directors can be persuaded to include or exclude an exceptional item. I wonder if it depends on whether it will have a positive or negative impact on reported figures.

Article 13.4 - Buttressed builder

LOMBARD COLUMN: Jonathan Guthrie

Consistency of accounting treatment is important for shareholders. It reassures them that they are comparing apples with apples, rather than oranges, and facilitates just comparisons with peers.

But looking at the reported operating profit margins at Taylor Wimpey and Persimmon, two of the UK’s largest housebuilders, is a bit like comparing apples with penguins. This month, Taylor Wimpey delivered a self-proclaimed sector-beating 9.3 per cent first-half operating margin. The 9 per cent figure Persimmon announced on Tuesday looked a bit measly by comparison. There is, however, a special ingredient to Taylor Wimpey’s apparent triumph over its more conservative rival. Included in its profits was a £48.9m gain from land sold for more than its estimated value. But during the recession the impairment on the very same land was deducted as an “exceptional” and was not reflected in the operating margin.

The company has done the accounting equivalent of having its cake and eating it. Discount the yo-yoing of its once “exceptional” slice of British turf and Taylor Wimpey’s margins look less healthy at 3.3 per cent. A neat piece of financial footwork. But one that has annoyed peers and will be hard to repeat a second time around.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 23 August 2011.

© The Financial Times Limited 2011. All Rights Reserved.

Stock (inventory) valuation

Year-end stock displayed in a company’s balance sheet normally consists of a mixture of raw materials, work in progress (incomplete items still being worked on) and finished goods ready for sale. The rule on stock valuation is that it should be shown on the balance sheet at cost or net realisable value (what someone might reasonably expect to pay for it),4 whichever is lower. Identifying the cost of some items of stock is relatively easy. If the company buys 100 tonnes of steel as a raw material input to its processes then it has invoices to look at. But consider the difficulty of valuing an incomplete car half-way down an assembly line. You might be able to isolate the costs of the material actually used, but how much of the factory overheads and the company’s general overhead should be allocated to the cost calculation for the car?

Overheads are business expenses that range over the operations as a whole and are not directly chargeable to a particular part of the work or product. So the costs of the factory managers and the factory rent relate to the costs of all cars produced in the year and not to any particular one. The accountant, when valuing a half-finished car, will add together the easily identifiable direct costs with the difficult-to-apportion production overhead costs. With overhead allocation there is much room for disagreement and also much room for putting on a positive gloss. The higher the year-end value, the lower the cost of manufacturing the cars sold during the year and therefore the higher the profit figures. A £1,000 increase in year-end stock value feeds into a £1,000 rise in profits. Also the balance sheet can be shown in a healthier light, with more assets relative to debts.

Some employees at GKN thought the managers too optimistic in their assessment of yearend inventories.

Article 13.5 - How a long-simmering US ‘quagmire’ shattered GKN

By Peggy Hollinger and Michael Pooler

Investors are pushing GKN to bring in an outsider as chief executive to replace outgoing Nigel Stein after the aerospace and automotive components company.

The FTSE 100 company’s shares still have not recovered from a month of bad news about its North American aerospace business, which led to the abrupt departure of Kevin Cummings, former head of aerospace and chief executive designate.

The revelation that GKN would have to write off mountains of overvalued inventory and unpaid bills in its US aerospace factories has severely dented the credibility of management and the board. Their judgment in giving the top job to the former head of US aerospace has been questioned as details of the problems emerge. But for anyone with an inquiring mind and an internet connection, the warning signs that all was not well in North America were evident as long ago as 2015. They continued flashing in the months and weeks ahead of company’s first revelation in October of a £15m writedown and then its second in November of a further £80m-£130m charge.

“What a sad state of affairs,” said one employee in GKN’s St Louis factory on the company ratings website Glassdoor last April. “In all my years I have never encountered such a quagmire … Operations build what will help them meet revenue, not what’s due to customers … Parts are not scrapped so they don’t have to be written off.”

Back in December 2015, a former St Louis employee with more than 10 years’ service also described “$10s [sic] of millions in ‘working inventory’ and finished goods that is scrap or obsolete materials and parts”.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 4 December 2017

© The Financial Times Limited 2017. All Rights Reserved.

Depreciation

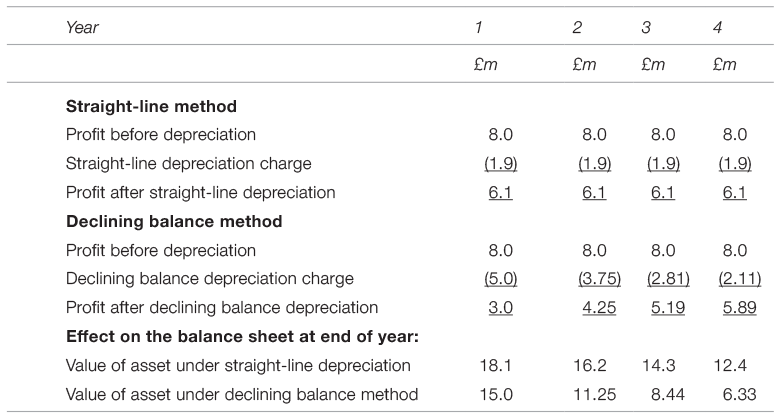

Imagine that your company has just purchased a state-of-the-art, computer-controlled machine for its manufacturing operations at a price of £20 million. The managing director estimates that it will have a useful economic life of ten years and at the end have a second-hand sale value of £1 million. She is in favour of straight-line depreciation, which means that the same amount is charged each year to the profit and loss account for the cost of using the machine.5 The cost less the residual value is £19 million. This is divided by ten years to give a depreciation charge of £1.9 million per year.

The production director, on the other hand, thinks that the machine will wear out much more quickly. He prefers to use the declining (reducing) balance method of depreciation. He thinks the appropriate rate in this case is 25 per cent per year. Thus, the machine will be depreciated each year by 25 per cent of the balance sheet value at the start of the year. In the first year £5 million is charged to the profit and loss (25 per cent × £20 million). In the second year 25 per cent of £15 million (balance sheet value at end of first year) is charged (£3.75 million). In the third 25 per cent of £11.25 million is charged (£2.81 million) and so on.

Both methods are permitted under the accounting rules, and yet choosing one rather than the other can have a dramatic effect on profit and asset levels. Imagine that profit before the depreciation expense is charged is £8 million per year, the machine represents the only asset the firm has and there is no debt. Then the profit patterns under these two methods look quite different (see Table 13.1). Profit appears to be on a rising trend in the second case – soon to overtake the static profit in the first case.

After four years the asset value is still over £12.4 million under the straight-line method, but only £6.33 million under the declining balance method. Imagine that the numbers in Table 13.1 represent two identical firms, and that the only difference is the method used for depreciation of fixed assets. If you were analysing these four years you would need to dig out the notes to the accounts in the hope that you could find the basis on which depreciation was calculated and then make adjustments in order to compare the performance and balance sheet strength of the two.

Of course, you should discover that the two, at base, are identical, but frequently there is insufficient information to reach that conclusion and the superficial appearance of the profit and loss account and balance sheet persuades investors that one company is more sound than the other when the only difference is the optimism or pessimism of the management about a long-term asset that may or may not have a ten-year life.

Wm Morrison, the supermarket chain, in 2014, decided to relax its depreciation policy. This boosted profits by £192m, but the shares fell as investors worried about ‘earnings quality’. The company had switched to assuming equipment, fixtures and fittings would last 13 years, more than double its previous estimate.

Even worse, although the two depreciation methods shown in Table 13.1 are the most commonly used, they are not the only ones permitted – there are at least four other methods for managers to choose from at their discretion. In addition, companies can play tricks by being more optimistic on the residual value (the sale value of the asset when the company has finished with it). The potential for manipulation is huge, and all within the rules of the game.

Managers sometimes change the depreciation policy, sometimes for legitimate reasons (the asset suddenly has a new lease of life and should be depreciated in a different way), and sometimes simply to make the accounts look better. So what is the investor to do? The answer is to examine the statement on depreciation methodology in the report and accounts. You can also derive evidence on depreciation policy change by comparing the amount of depreciation with the value of assets: Do the proportions change over time? A fall from 12 per cent to 5 per cent, for instance, may set alarm bells ringing, as managers may be deliberately underestimating wear and tear and obsolescence of assets.

Capitalisation

When a company spends money on something there are two possible consequences: either an asset is acquired which then goes into the balance sheet, or there is an expense to be charged to the profit and loss. It is possible to boost profit and the balance sheet asset values by taking the view that a greater proportion of spending is for the acquisition of assets rather than for expenses. With assets such as buildings there is little problem with stating a capital value in the balance sheet. However, with spending on items like research and development we have the potential for rose-tinted spectacle distortion. As stated earlier, companies are allowed to capitalise development expenditure for clearly defined projects with near-certain commercial success – that is, show it on the balance sheet as an asset. This subjective test is all the flexibility that creative accountants need.

Alongside development expenditure, managers are often permitted to capitalise interest on a project during construction. So a property construction company that paid £100,000 for building land, £900,000 to build and £200,000 of interest during construction may have a stated balance sheet value for that property of £1.2 million. Under the rules, capitalisation of interest is supposed to stop after completion of the building. However, some companies have been known to extend this period of ‘construction’ over a considerable time period, thus tying up more interest as an ‘asset’ in the balance sheet.

Supermarkets often capitalise the interest incurred while building a supermarket. This is then written off gradually under the company’s normal depreciation policy. Capitalisation of interest has also been used by ship and aircraft manufacturers, and producers of whisky (a ‘good’ that takes a long time to ‘construct’). The problem is that some managers and acquiescent accountants and auditors have taken the process too far.

The analyst needs to take particular care when calculating the interest cover ratio (see Chapter 12) for a company with a propensity to capitalise interest. The interest paid and charged to the profit and loss can be a small fraction of that sent straight to the balance sheet to be capitalised. You need to add both interest figures together to get a view on the level of payments to lenders relative to profits (look at the interest charge in the cash flow statement).

It is also considered acceptable to capitalise some starting-up costs (costs of running in new machinery or testing equipment). Again the absence of precise definitions for what can and can’t be capitalised provides the loophole some managers and accountants are looking for.

Off-balance-sheet items

Investors may be worried not about the treatment of items that are actually shown in the balance sheet, but about commitments the company has entered into, but which are not shown in the balance sheet. These off-balance-sheet items can seem to appear out of the blue to destroy a company. For example, Enron, the disgraced Texas energy trader, used special-purpose entities to manipulate its profits and the appearance of its balance sheet. Special-purpose entities are set up as separate organisations and their accounts are not consolidated with the rest of the group – which can be useful if you want to hide a vast amount of debt or expenses. Not all special-purpose entities should be viewed with suspicion as some have legitimate uses, for example, to finance a research and development partnership with another company, or for repackaging some of the company’s assets and then selling these on to investors (securitisation). However, special-purpose entities are a useful tool in the hands of dishonest managers.

In the UK there have been fewer scandals with special-purpose entities and other off-balance-sheet financing techniques than in the US. Perhaps this is due to the accounting rules insisting that, regardless of the technical position, managers and accountants are required to report the substance of a transaction. Accounts are supposed to reflect the underlying reality of the situation. Having said that, some grey areas remain. For example, banks take on numerous risks in the derivatives markets. They might have to face significant liabilities if certain events come to pass (for example, interest rates rise or fall by large amounts – many of these risks do not appear in the accounts).

Another grey area used to be the presentation of lease commitments. Take a company needing to acquire the use of a new machine. It could go out and buy the machine for £1 million, using a bank loan to do it. A disadvantage of this is that the debt–equity ratio (gearing) rises because of the new loan. An alternative is to lease the machine for say, £10,000 per month. The company has not borrowed £1 million and so the balance sheet is not burdened. However, with many of these lease agreements the company is making a strong legally binding commitment to make regular payments: at least as strong as it would if it was paying off a bank loan. So the substance is much the same, whether the asset is leased or bought with a bank loan.

Back in the 1980s the accounting profession made a big step in closing this loophole. If the lease transfers substantially all the risks and rewards of ownership of an asset to the company over the course of the lease then it has to be classified as a finance lease. This means the machine is recorded as an asset and the obligation to pay future rentals is recorded as a liability on the balance sheet.

Other leases are referred to as operating leases. Under the old rules the assets and liabilities under operating leases did not have to be displayed on the balance sheet. While many lease obligations are made explicit to investors, this remained a tricky area because it is often very difficult to declare one lease as ‘transferring substantially all the risk and rewards of ownership’ and another lease as not doing so. Airlines, for example, were very adept at signing up for aircraft rentals that just fall into the category of operating leases and thereby clear their accounts of large numbers of aircraft as assets, and the associated leases as liabilities.

From 2019 companies were forced to put operating lease liabilities on balance sheets. The amounts the firm has committed to paying in rent over the next few years is a liability while the item, whether that be an aircraft, truck or warehouse, becomes an asset. The greatest impact will be felt by retailers with all those long shop leases – Debenhams has lease commitments of £4.3 billion. The liabilities for many airlines will rise very significantly too – Flybe has £217 million of lease obligations.

Another off-balance-sheet liability used to be the amount companies owe to the pension scheme set up for employees. There was much heated discussion as to whether companies should place this as a liability on their balance sheet. The case for ignoring it is that the amount owed varies from one year to the next and so the accounts would become volatile for reasons unconnected with underlying trading. Investors would then be confused by the extra information, and this would lead to wrongly priced shares. This is a self-serving argument in most cases. Some companies have pension liabilities that dwarf the assets of the business. Nowadays pension liabilities are generally on-balance-sheet.

Share (stock) options

Imagine you own 50 per cent of the shares in X plc. There are 10 million shares in issue. The company has a share option scheme in which directors are entitled to buy, in three years’ time, 1 million shares at £1 each (the same as the current share price). Now imagine that the three years have passed and the share price has risen to £3. The directors have a bonanza. They can now exercise the option to purchase £3 million worth of shares for a third of the price.

This type of scheme is quite common and can be useful to incentivise managers. However, the difficulty comes in accounting for share options. Suppose the company at the end of the three years is making annual profits of £2 million, so before the exercise of the options you, as a 50 per cent shareholder, have a £1 million claim on the profits – 20p per share. If the options are exercised the number of shares in issue rises to 11 million. Then each share has a claim on only £2m/11m = 18.18p. Your claim is 5m × 0.1818 = £909,090. You have lost out because the directors now have a claim on 9 per cent of the company’s profits.6 This is a cost to you, the shareholder.

In the past most companies failed to properly acknowledge share options as a cost to the shareholders – the best that was offered was a note in the accounts. Thousands of directors became very wealthy as a result of share option schemes. That wealth came from somewhere, and yet rarely was the cost to shareholders properly recorded. Sure, the earnings per share figure was ‘diluted’ to allow for the possibility of the issue of additional shares, but the headline profit reported on the face of the accounts generally ignored the cost.

If managers had been incentivised through a cash bonus scheme of £2 million, this would have been highly visible and profit would have been depressed. Given this, why not express the share-option-based transfer of shareholder wealth as a cost? The accounting regulators now insist that the value of options be assessed at the date they were granted, even if they are ‘out of the money’ (see Chapter 8) and charged to that year’s income statement. This is different to either (a) ignoring option values (as UK companies used to do) or (b) only valuing the option when and if it is exercised, or (c) only valuing the option prior to the exercise if it has intrinsic value, that is, the option is ‘in the money’. The main problem with the solution chosen is that the models used to calculate out-of-the-money option values are complex and full of bold assumptions.

Missing the profits and assets in investee companies

This is an accounting problem that generally leads to under-reporting of the company’s performance. When a company owns say 10 per cent of the shares in another company it will only bring into its consolidated profit the dividends it received and not the full 10 per cent of the investees earnings. Warren Buffett explains this well below. (GAAP is the US accounting rules ‘Generally Accepted Accounting Principles’.)

Box 13.2 - Calculate ‘look-through’ earnings

Investors must always keep their guard up and use accounting numbers as a beginning, not an end, in their attempts to calculate true “economic earnings” accruing to them.

Berkshire’s own reported earnings are misleading in a different, but important, way: We have huge investments in companies (“investees”) whose earnings far exceed their dividends and in which we record our share of earnings only to the extent of the dividends we receive. The extreme case is Capital Cities/ABC, Inc. Our 17% share of the company’s earnings amounted to more than $83 million last year. Yet only about $530,000 ($600,000 of dividends it paid us less some $70,000 of tax) is counted in Berkshire’s GAAP earnings. The residual $82 million-plus stayed with Cap Cities as retained earnings, which work for our benefit but go unrecorded on our books.

Our perspective on such “forgotten-but-not-gone” earnings is simple: The way they are accounted for is of no importance, but their ownership and subsequent utilization is all-important. We care not whether the auditors hear a tree fall in the forest; we do care who owns the tree and what’s next done with it.

When Coca-Cola uses retained earnings to repurchase its shares, the company increases our percentage ownership in what I regard to be the most valuable franchise in the world. (Coke also, of course, uses retained earnings in many other value-enhancing ways.) Instead of repurchasing stock, Coca-Cola could pay those funds to us in dividends, which we could then use to purchase more Coke shares. That would be a less efficient scenario: Because of taxes we would pay on dividend income, we would not be able to increase our proportionate ownership to the degree that Coke can, acting for us. If this less efficient procedure were followed, however, Berkshire would report far greater “earnings.”

I believe the best way to think about our earnings is in terms of “look-through” results, calculated as follows: Take $250 million, which is roughly our share of the 1990 operating earnings retained by our investees; subtract $30 million, for the incremental taxes we would have owed had that $250 million been paid to us in dividends; and add the remainder, $220 million, to our reported operating earnings of $371 million. Thus our 1990 “look-through earnings” were about $590 million7.

Source: Warren Buffett’s 1990 Chairman’s Letter to Berkshire Hathaway Shareholders. Reprinted with the kind permission of Warren Buffett © Warren Buffett.

Other tricks

Companies sometimes emphasise ‘pro-forma’ accounting numbers, which are prepared to exclude those items that the manager regards as unusual and non-recurring items for a recent past period, or when stating how much money the company will make on some assumed events and transactions that have not yet occurred. This is often a deliberate distraction tactic employed by companies that are currently making accounting losses. Pro-forma numbers remove many negative items from the profit and loss account in a manner that may not, in any way, comply with the accounting rules. Pay no attention to pro-forma figures. See Article 13.6 for some examples. Note the resistance in US boardrooms to regarding share (stock) options as a cost.

Companies sometimes try to load losses on to operations that are going to be discontinued. Because continuing businesses and discontinued businesses are separated in the profit and loss account, it becomes possible to direct investors’ attention to the continuing business and then bury losses in the non-continuing businesses section.

Firms sometimes fail to write down (write-off) worthless assets.

Fun and games can also be had with changes in foreign exchange rates impacting on assets, liabilities, revenues and costs.

Article 13.6 - Accounting exceptionalism has become harder to ignore

By Richard Waters

The costs being stripped out in company results are growing.

Twitter’s red-hot IPO and regulatory warnings about the flattering light in which some internet companies like to present their performance have revived memories of the dotcom bubble. With stock prices soaring, it has become tempting for fast-growing companies to stretch conventional accounting rules.

But the biggest perception gap in the technology world involves a group of far more mature companies. As the pace of change in their markets accelerates and some of the industry’s best-known names face upheaval in their businesses, this gap looks set to widen further.

Look no further than that model of corporate probity, IBM. It wasn’t long ago that IBMers scoffed privately at rivals such as Hewlett-Packard for publishing pro-forma earnings. Such figures, known, inelegantly, as non-GAAP since they deviate from generally accepted accounting principles, tend to exclude costs that companies claim make it harder for investors to understand what’s happening in their underlying businesses.

Three years ago, IBM gave in to the prevailing mood and started stripping some costs from its preferred measure of earnings (in its case, some employee retirement costs and charges related to acquisitions.) Like others, IBM is still required to report official earnings with all costs included, but it uses the non-GAAP numbers when talking to Wall Street.

It is not obvious for investors which measure of IBM’s profits they should care most about. After its second quarter this year, Big Blue put the spotlight in its press release on an earnings per share figure of $3.91 – a number deemed “most indicative of operational trajectory”, since it excluded $1bn in “workforce rebalancing” charges.

But in its official quarterly filing, IBM added back the lay-off charges and settled on a different non-GAAP number of $3.22. Both were higher than the $2.91 a share it recorded under official accounting rules.

The amounts that are being routinely added back to profits have become staggering. For tech companies in the Standard & Poor’s 500, they amounted to $40.7bn in 2012. The difference boosted the profits these companies earned under standard accounting rules by 36 per cent, according to Jack Ciesielski.

The companies, and the analysts who follow them, have largely justified this behaviour on the grounds of tech industry exceptionalism. This argument holds that they are not like other companies due to the larger amounts of stock they issue to attract and reward workers.

Formal accounting rules require this to be deducted from earnings. Most companies argue that issuing shares isn’t a direct cost on the company – and that current valuations of the future stock benefits are largely meaningless anyway, so it is better to exclude them.

Whatever side you take on this issue, though, it turns out to be a sideshow. Stock benefits only accounted for a quarter of the costs that tech companies added back to profits in 2012, according to Mr Ciesielski. The other 75 per cent was not so different from the sort of things that companies in all industries face.

The costs added back to earnings last year included: charges related to acquisitions (four companies did this), restructuring costs (three), amortisation of intangibles (two), asset impairments (two) and fines and legal judgments (two).

Individually, and in any given year, the companies that try to gloss over charges such as these might have some success in arguing that they are one-offs.

But collectively, and with the numbers growing from year to year, it becomes much harder to sweep all the industry’s bad news under the rug.

Many of these one-off costs are coming to look like business as usual. It is up to investors to decide how much of this they can afford to ignore.

![]()

Source: Financial Times, 13 November 2013.

© The Financial Times Limited 2013. All Rights Reserved.

Concluding comments

So what is the time-pressed investor to do, given all this potential for trickery? First of all, don’t panic. The vast majority of managers are honest and like to present an accurate picture of the state of affairs of the company. Even those tempted to flatter the figures will be restrained by the accounting standards and the necessity of adding a note to the accounts where they have viewed an element in a particularly favourable light. They are also inclined to integrity by the fact that a lot of the tricks will be revealed to investors over the medium term – they might get away with it for a year or two but eventually the truth will out. Smart managers, with a long-term career to think about, recognise the necessity of straight dealing. Most try to avoid weaving tangled webs.

Having said that, not all managers and accountants are as straight as we would like, so here is a list of what you can do to avoid being taken for a ride:

- Pay close attention to the notes to the accounts: Many analysts read the accounts backwards working from the notes, through the cash flows, balance sheets and profit and loss until finally reaching the points that were supposed to impress (and possibly mislead) them at the front of the annual report and accounts. Reading the notes first will highlight issues tucked away, such as goodwill, amortisation, exceptional items and capitalised interest that will not be presented in the profit and loss, balance sheet and cash flows. When you reach the main accounts you will have the information to allow you to make adjustments so that ratio analysis is more meaningful. When reading the accounts ask yourself which numbers you would manipulate if you wanted to bias the figures.

- Get data from other sources: Brokers’ reports can give a critical appraisal of the company’s accounts. You can obtain information about the directors’ past lives by, say, conducting an internet search – tap their names into a search engine and see what comes up. Industry analyses are available from the specialist websites such as Dun and Bradstreet (www.dnb.co.uk), but you can find out a lot about an industry for free by simply browsing the web.

- Focus on cash: Being creative with cash flow figures is much more difficult than being creative with profits and balance sheets. Be sceptical about companies that show high and rising profits with low cash flow. A very useful measure is the cash return on capital employed in the business. It suffers far less from biased accounting than earnings-based measures.

- Check accounting policies: If accounting policies, such as on depreciation, have changed from the previous year then watch for the effect on profits. Ask questions such as: Does the reduction in depreciation boost profit artificially, or is it justified? If there is not enough information in the accounts then you could ring the investor relations department of the firm to ask for an explanation of the accounting policies.

- Meet the management: The issues of creative accounting and fraud are fundamentally issues of trust. If you attend AGMs and regularly scrutinise the directors’ public statements you may instinctively sniff out suspicious characters. For instance, if managers one year try to direct your attention to earnings per share, and the next to EBITDA, and in the third year they emphasise operating profits, you may start to suspect that they are more interested in short-term appearances than in creating long-term value. They are certainly not interested in communicating their (inevitable bumpy) progress in a frank and unspun way. If year after year the firm comes up with pathetic excuses such as an ‘early Easter’ or ‘bad weather’ for poor performance rather than occasionally putting their hands up and saying that the strategy had gone awry, you have reason to doubt the management’s honesty – with themselves, let alone with investors.

- If in doubt, don’t take a punt: If you are not sure about the quality of the numbers, or cannot see clearly what is going on, then don’t allocate some of your precious fund to the company. Investors can afford to let many balls go past them until they get a perfect pitch that they can hit cleanly and relatively safely.

Further reading

W. McKenzie The Financial Times Guide to Using and Interpreting Company Accounts (Financial Times Prentice Hall, 2009).

E. McLaney and P. Atrill, Accounting and Finance: An Introduction, 9th edition (Pearson, 2018).

A. Thomas and A W Ward, Introduction to Financial Accounting, 8th edition (McGrawHill, 2015)

A. Sangster, Frank Wood’s Business Accounting Volume Two, 14th edition (Pearson, 2018).

B. Vause, Guide To Analysing Companies, 6th edition (The Economist Books/Profile Books, 2014).

_______________

1 The stated value is the value derived from the accounts. The fair value is the amount an asset could be exchanged for in an arm’s-length transaction between informed and willing parties.

2 However, the rules insisted that some note on accumulated goodwill write-offs be presented in the notes to the accounts.

3 To be capitalised it must be possible to separate these assets from the rest of the business and sell them. There must be a ‘readily ascertainable market’ for internally generated assets to be valued in the accounts. If the asset is not amortised at all or is amortised over a period greater than 20 years it will be subject to review for impairment annually.

4 Net realisable value is calculated after deducting all further cost to complete the item and all costs of the selling process.

5 The term ‘depreciation’ is generally applied to tangible fixed assets, whereas ‘amortisation’ is used for intangible assets.

6 Admittedly, directors have boosted the company’s cash by £1 million, but this is insufficient to offset the loss.

7 If you would like to learn more about the world’s greatest investor then you might like to look at my series of books The Deals of Warren Buffett (Harriman House 2017, 2019) for case studies of his investments, The Financial Times Guide to Value Investing (Pearson, 2009) or Great Investors (Pearson, 2010) for short introductions, or for the latest Buffett cases and application of his investing principles, see newsletters.advfn.com/deepvalueshares