Overview of Distributed Decision-Making Process

Who makes the decision? What kinds of decisions do people make at the workplace, and for what reasons are they carried out, and when are they needed? If at all, can one transfer or empower the responsibility of making decisions to others? To answer these questions, let me first define what decision making is. According to Saaty (2012), making decisions in organizations undergoes a multifaceted process based on many intricate and challenging issues, despite the fact that people need to make decisions at all times and at all levels. He further suggests that decision making is a complex world, and it is governed by two dimensions, which are the human behavioral and thought process. The human behaviors are driven by the instinct–drive theory, which describes how a person is subjected to one’s own instinct when making decisions. As such, factors like sentiment, value, ambition, attitude, taste and preferences, and inclination are seen as more desirable compared to logic reasoning and logic thinking. Saaty (2012) also further integrates the theory of learning to understand how a person makes a decision. He defined learning as “…the ability to recognize a specific act in the light of previous experience. It is an iterative, or repeated, process of adding knowledge that elaborates on or expands existing knowledge” (p. 9). With both theories at hand, it is interesting to explore whether or not such intuitive and learning behaviors of people at the workplace provide an understanding on how the different work structures, such as the virtual work environment, play out when it comes to the decision-making process.

Essentially, given the heightened level of globalization and the ubiquitous use of computer-mediated technologies in organizations at present, people are confronted with new ways of making decisions at a virtual workplace. Thus, with this entire complex distributed decision-making process, it is essential to understand that the decision-making process is still the root of management roles in any organizations. In a globalized world, the reality of workplace presents each employee at multiple layers of management with varied types of decisions for diverse reasons at a different time zone with different practices as well. In fact, in all organizations, all layers of management are involved in decision making—i.e., one way or another—whether or not it is for a simple or challenging task at the workplace. For example, on a daily and routine basis, no organization can operate without making decisions—either small or big ones. The only difference that sets apart one layer of management from the others is the degree of decisions to be made, by whom, and by when. Likewise, on a long-term and competitive basis, no organization can excel without making timely and accurate decisions within a strategic time frame. If organizations regard time as money, then decisions are costly. High-performing organizations depend on efficient decisions and effective action plans. The phrase money talks becomes the main agenda for any organization to incorporate its strategic plan of maximizing profits and minimizing costs. The goal of making profit is the bottom line for all organizations.

Many organizations consider the decision-making process as the heart of organizational process, culture, and structure; thus, for the distributed decision-making process to be effective, organizations need to consider such process as both a science and art in itself. Moreover, for global virtual teams (GVTs), given the complexities of distance and time zone, decisions need to carefully incorporate the scientific process because, in every step of a decision, people need to explore situations and problems, then identify the choices when they need to solve a problem, consequently think carefully about the problems and the choices at hand, deliberate the ideas among people, and finally arrive at a solution by taking appropriate actions. It is in a scientific manner because it follows a systematic way of doing things—involving one process to another, which has a beginning and an end. This process itself can be time consuming because the members are from different geographical locations with different time zones. Yet, GVTs are also confronted with many challenges in arriving to a decision, as well as realizing an action due to cultural differences such as in communication styles, work practices, and procedures. This is where the aesthetic or creativity element comes into the picture. The art of decision making entails a manager to solve a problem and find a solution through an innovative way by taking the cultural elements into perspective. It may result in diverse ways of solving a problem to reach efficient and effective decisions. People, organization system and structures, work policies and procedures, and technology are some of the key aspects that need to be put in place at the organizational level. Yet many of the organizations failed to take into consideration the magnitude and impact of the virtual-space factors when they manage their GVTs due to members coming from different organizations. They failed to incorporate both the scientific and innovative manner of managing the distributed decision-making process.

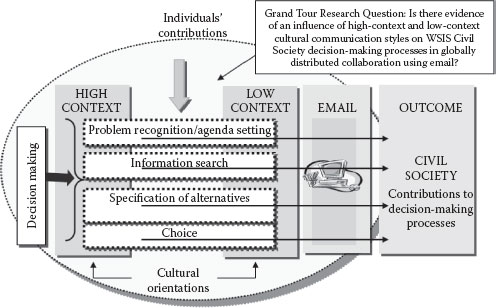

Therefore, this study focused on email participation and did not consider other computer-mediated communication (CMC) tools such as blogs or Wiki Webs, or Web conferencing, or face-to-face meetings. Effective participation in the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) was measured by the substantive contributions that were made by Civil Society participants during the four stages of the decision-making process: (1) problem recognition/agenda setting, (2) information search, (3) specification of alternatives, and (4) choice. I investigated the communicative behaviors from two distinct cultural orientations, high context and low context, since an individual may contribute in the four stages differently depending on whether he or she uses high-context versus low-context cultural communication styles and the cultural values that one is ascribed to.

The first stage in decision making is problem recognition (Adler 1997). It was crucial for participants to correctly identify and recognize the problems that they wanted to solve or bring to attention in the WSIS. This is the initial step in the decision-making process. In public policy-making processes, Kingdon (1995) termed this stage as agenda setting. The second stage is a response to problems and issues, which Adler termed as information search. At this stage, once people identify the problems, as well as begin to look for ways to solve them, they would provide many responses as a way to search for information that helps them make a decision on the most viable solution for the problem encountered (Adler 1997). The third stage is specification of alternatives in which people choose from a range of options (Kingdon 1995). In this stage, it centers on the ability of a Civil Society participant to make a proposal by giving or generating ideas, and presenting a position on the problems identified, or putting across self-interest issues. The final stage is called choice where a solution (one or many or even a nonsolution) is arrived at either by consensus or by authoritative action. It is noteworthy that success in one of these stages is not an indication of success in others. In addition, the stages do not necessarily occur in a linear fashion. The stages are iterative and interdependent and may occur several times before a solution is reached and/or agreed upon by participants. Likewise, some stages can be left out. The most effective process is that participants reach a solution that addresses the problem and that arises from the proposals made and the responses generated.

In phase one of the WSIS in Geneva, the outcome was to generate two documents—(1) Declaration of Principles and (2) Plan of Action. However, this study did not look at the impact of culture on the WSIS outcome but rather focused on the process—the effect of culture on the dynamics of Civil Society participants’ cultural communicative behaviors using email (as pointed out in the circle area of Figure 7.1). The decision-making processes are only based among and within Civil Society participants and not on the overall WSIS processes that include the other two multistakeholders—(1) governments and (2) private sectors.

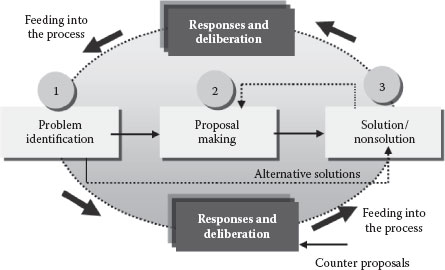

Initially, this study identified four stages based on Kingdon’s (1995) and Adler’s (1997) models. In a virtual work structure, the decision-making process will be amplified by several more factors. Distance, space, technology, and culture will pose challenges for managers to make decisions. Thus, by analyzing the data empirically, the stages of decision-making process were reduced to only three. The stage called responses and deliberation was integrated with the other three main stages because it was observed that participants continuously provided responses that became a cyclical feedback that fed into the three key stages. Thus, the stage called responses and deliberation was no longer considered one stage by itself. In this study, I defined effective participation based on two criteria: (1) quantity—number of emails and frequency and (2) quality—substance of emails.

Figure 7.1 Conceptual framework of globally distributed collaboration of Civil Society in WSIS using email.

■ Problem identification

This concerns messages in which participants identified a problem(s) or an issue(s). Some of the issues were in a form of question, while some were in a form of statement. This activity is crucial as it sets the initial tone for member participation; a well-stated problem is more easily solved than a poorly identified one.

■ Proposal making

This concerns how people generated ideas, as shown by how they present an idea or how they make suggestions to participants. From this behavior, I further looked for shared patterns of behavior among high- and low-context cultural orientations. For example, high-context people sent messages that were lengthy and ambiguous when they were proposing something, whereas low-context people sent messages that were terse, succinct, and directly to the point.

■ Solution

This concerns the manner in which a solution or decision is reached for each of the proposals made, again from a cultural standpoint. Each solution was considered a decision point. For this analysis, I looked only at proposals that had a decision. If the proposal did not have a decision point, I regarded it as an instance without a decision or solution.

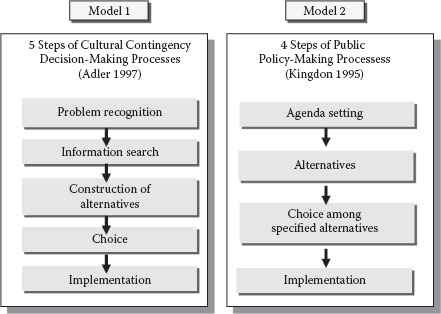

Theoretical Models of Decision-Making Process

In exploring the impact of culture on decision-making processes, I used a combination of two theoretical frameworks: (1) cultural contingencies of decision making (Adler 1997) and (2) public policy-making processes (Kingdon 1995). Adler proposes five sequential steps in decision making that have cultural consequences: (1) problem recognition, (2) information search, (3) construction of alternatives, (4) choice, and (5) implementation. Kingdon’s (1995) model identifies four steps: (1) agenda setting, (2) specification of alternatives, (3) choice among specified alternatives, and (4) implementation.

This framework is useful in understanding the policy-making processes in WSIS Geneva, beginning from the time that the listserv members identify a problem or an issue to the time that they reach a solution. Although Adler’s model has five stages, and Kingdon’s model has four, both describe a similar sequence of actions. Adler underlines decision-making processes as a crucial managerial task that is culturally bound (see Figure 7.2), whereas Kingdon’s model explicates the policy-making processes. It is useful to note that in Adler’s model, steps 2 and 3 can be collapsed to correspond with Kingdon’s step 2, thus enabling me to use both models. For the purposes of this study, I chose to model out the decision-making processes based on the synthesis of Adler’s first four stages and Kingdon’s first three stages and the final stage—implementation—is omitted (see Figures 7.1 and 7.2).

Based on Figure 7.2, the first step is problem recognition/agenda setting. Adler introduced the stage called problem recognition in which members identify and define the problem that they are facing and recognize the severity of the problem. According to Adler (1997), it is imperative to recognize “when is a problem a problem” (p. 168). At this stage, problem recognition is contingent upon culture in the sense that some cultures take longer to acknowledge or express problems, whereas other cultures immediately address concerns, issues, or problems at hand. Kingdon’s corresponding stage is agenda setting in which his concept of agenda alludes to the subject(s) being announced before a meeting begins. He defines agenda as “…coherent sets of proposals, each related to the others and forming the series of enactments its proponents would prefer” (1995, p. 3). He also suggests that agenda can mean the list of subjects or problems that need to be taken seriously at any given time. In this respect, the word agenda implies a sense of urgency.

Figure 7.2 Sequential models of decision-making processes. (Adapted from Kingdon, J.W., Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies, New York, Addison-Wesley Longman, 1995; Adler, N.J., International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, 3rd. ed., Cincinnati, OH, South-Western, 1997.)

The second step is to search for information once problems were identified. Adler posits that there are two forms of thinking when it comes to information gathering—(1) using logical order or (2) using intuition. Those people who use logical thinking gather information based on facts. On the contrary, people who use intuition or affective thinking gather ideas and possibilities based on relationship. Kingdon did not have a specific stage that is dedicated for information search, but his second step, called alternatives, does include this process.

The third step is to specify or construct the alternatives from which a choice is to be made. In this step, serious consideration is given to all potential alternatives. Adler suggests that once people have gathered sufficient and relevant information, they will begin to construct ideas or make proposals in order to address the problems identified. This process is shaped by the participants’ cultural backgrounds since it raises questions such as whether the alternatives are composed of predominantly new ideas or ideas that are rooted in the past and whether it favors ideas that demand large or moderate (or no) amounts of change. Once ideas are presented, people respond by challenging or supporting the ideas, which may result in alternatives being modified or removed from consideration. Kingdon (1995) argued that at this stage, “…the process of specifying alternatives narrows the set of conceivable alternatives to the set that is seriously considered” (p. 4). During this crucial stage, experts brainstorm to generate as many solutions as possible, while the preceding agenda-setting stage is normally taken up by a leader.

The fourth step is concerned with making an authoritative choice among the specified alternatives. In this stage, Adler suggests making a decision from the range of presented and debated options. For Adler, several questions can be investigated here, such as who makes the decision, how fast decisions are made, at what level decisions are made, how much risk is involved, in what order people discuss alternatives, and when people select particular alternatives. As in all the steps, these questions also have cultural variations. This corresponds to Kingdon’s (1995) third step in which he asserted that the most important thing is to understand how and why agenda items were selected for discussion in the first place, a question of “how they came to be issues” rather than “how issues are authoritatively decided by president, Congress, or other decision makers” (p. 2). This requires searching out for the underlying reasons why certain agenda items got picked over others; this is not an easy task since, as Kingdon (1995) puts it, “when a subject gets hot for a time, it is not always easy even in retrospect to discern why” (p. 2).

The final step in both Kingdon’s and Adler’s model is implementation, which provides closure to the actions that were taken in steps 1 through 4. This study did not analyze the implementation step since the focus of the study was process, not product. In the first phase of WSIS (Geneva), the final decisions were made by the government, so no decisions made among and within Civil Society members in the listserv were final or binding. Until the government made its decision, no implementation could take place; thus, this stage was not applicable in the context of Civil Society participation in the WSIS Geneva process.

In order to provide a general understanding of WSIS and the magnitude of the activities that took place in the period of 33 months, I will first describe the activities that took place in the Civil Society plenary listserv during the WSIS (see the “Active Months of Participation” section). Subsequently, in the said section, I will only focus on the WSIS Civil Society decision-making processes during WSIS Geneva and then compare the empirical model with the adapted models of Kingdon and Adler.

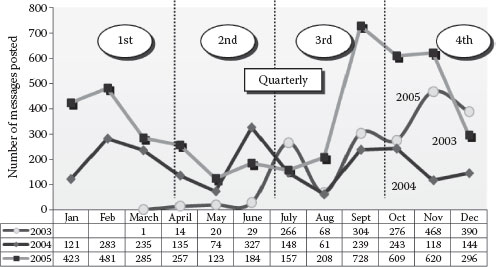

The WSIS listserv generated a total of 8,335 email messages from March 2003 to December 2005 (see Figure 7.3). This massive amount of email messages points out the significance of distributed collaborations among and within Civil Society participants in the WSIS process. On a broader perspective, participation was not constant during that period; there were months that generated heavy email traffic, whereas there were months that generated less traffic. For example, during WSIS Geneva, November (n = 468) and December (n = 390) generated the heaviest traffic because the summit took place in December 2003, so the collaborative efforts were gearing up for the summit event. Similarly, in WSIS Tunis, the few months before and during the summit in 2005, September (n = 728), October (n = 609), and November (n = 620), showed a higher number of messages compared to any other preceding months. The face-to-face preparatory conferences and regional meetings also corresponded with and contributed to an increase in email discussions (see Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Email participation of Civil Society in WSIS Geneva and Tunis.

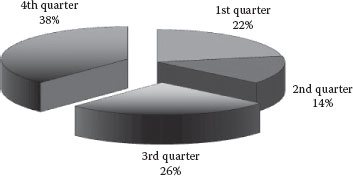

On the overall situational analysis of email use (see Figure 7.3) from 2003 to 2005, the last four months of the year (n = 4,435) showed a heavy traffic of messages. For example, September (n = 1,271), October (n = 1,128), November (n = 1,206), and December (n = 830) all generated large numbers of email messages. These months accounted for 53% of the total messages. Some months were obviously less active such as from March to May (n = 1,144), which accounted for only 14% of the total messages. Looking at the quarterly trend for the period between 2003 and 2005 (see Figure 7.4), it is evident that the WSIS process generated more collaborative activities during the third and fourth quarter of the year, respectively, 38% and 26%, which means that 64% of the collaborative efforts were inclined toward the last six months of the year. This time of the year also corresponded with the face-to-face meetings preceding PrepCom 3 and the summit events.

Figure 7.4 The proportion of email messages per quarterly period of 2003–2005.

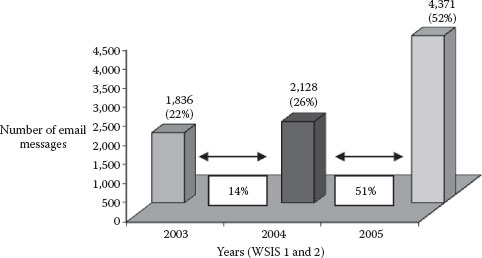

As Figure 7.5 shows, there was a regular increase in the number of email messages throughout WSIS Geneva and Tunis. In 2003, the archival messages totaled 1,836, which represented 22% of the total messages. In 2004, the total messages increased to 2,128, a minimal increase of only 14%, which represented 26% of total messages. In 2005, the number of messages was 4,371, an increase of 51%, which was almost twice the number of messages than the previous year. This 2005 total accounted for 52% of the bulk of the email traffic over the three-year period. With the increase in email messages from one year to another, it is evident that Civil Society used email as the primary tool not only for communication but also for collaboration, enabling them to effectively participate and contribute to the decision-making process in the WSIS.

Figure 7.5 Civil Society email participation in WSIS process (2003–2005).

Active Months of Participation

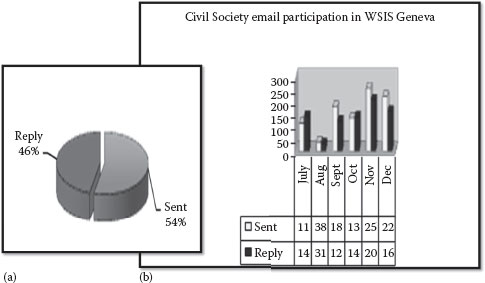

As shown in Figure 7.6b, the empirical findings of the study only focused on Civil Society participation in the virtual plenary listservs in WSIS Geneva. WSIS Geneva had a total of 1,836 messages with 223 Civil Society participants participating in the email listserv from April to December 2003. Figure 7.6a shows that there were few email messages from April to June 2003—a total of 63 messages, representing only 4% of the total messages. These months were slow since those were the months when the email listserv was just set up by Civil Society plenary. Officially, the listserv was created in April 2003, although the preparatory meetings for both WSIS events took place much earlier via physical or face-to-face meetings (see Figure 7.3). The few emails were not substantial in content; in fact, most of the email was an auto-reply message in April and May. In June, there were a small number of discussions centered on the preparation for the meeting in Paris, the structure of Civil Society, and the issue of translation.

Figure 7.6 (a) Proportion of sent and reply messages (July–December 2003). (b) Active months of participation.

Therefore, the analysis was conducted on data from a six-month period (July to December 2003) because these were the most active months in terms of observable online communicative and collaborative behaviors. As seen in Figure 7.6b, Civil Society participants posted 1,760 email messages with 222* participants from July to December 2003. On average, eight messages were posted by each member over the six-month period or 1.33 messages each month. The maximum number of messages posted was 121, posted by a focal member who moderated and organized the plenary listserv.

It was not until July that substantial discussions began both in the content and number of emails posted because the participants were preparing and setting the agenda for the many ongoing face-to-face meetings such as the Paris Intersessional Meeting in mid-July and PrepCom 3 that took place in September, November, and December. Most importantly, these are the last six months in which Civil Society had the opportunity to make a strong contribution to the outcome of WSIS Geneva by influencing the content of the Declaration of Principles and Plan of Action. Figure 7.3 shows the high traffic of messages during the three months (July, September, and November) surrounding the important events outside the email discussions as mentioned earlier in this section. The increment observed in those three months represented almost 50% of the total email messages, which indicated the importance of those three months.

Figure 7.6a shows an analysis of the CMC participation in terms of the messages sent and messages replied by Civil Society participants. The analysis shows that the messages posted outnumber the replied messages, 54% to 46%. However, there were not many differences between the two activities (n = 144), which accounted for only 8% of the total messages.

Distribution of Active Participants

Based on the average number of emails, the findings showed that 57 Civil Society participants were active participants in the WSIS Geneva process (see Table 7.1). As mentioned in the “Active Months of Participation” section, on average, each participant posted eight messages during the six-month period. Active participants, for this analysis, are defined as those that generated above the average number of emails (n = 8). Hence, for the six-month period, only 25% of the total membership (n = 222) were considered active participants out of the total number of participants in the plenary listserv. The active participants generated a total of 1,351 messages. Although the percentage of active participants was low, they generated 77% of the total volume of emails posted (n = 1,760). Each active member sent out an average of 24 messages during the six-month period, and active participants generated an average of 224 mails per month (see Table 7.2).

Table 7.1 Overall Patterns of Civil Society Participation: July–December 2003

Activities | Total |

Total email messages sent by all participants | 1,760 mails |

Total number of participants during six months | 222 participants |

Average message sent per participant | 7.93 = 8 mails |

Table 7.2 Overview of Active Participation: July–December 2003

Activities | Total |

Total number of active participants | 57 participants |

Total email messages sent by active participants | 1,351 mails |

Average message sent per active participant | 24 mails |

Average message sent per month by all active participants | 225 mails |

As shown in Table 7.3, there were three key people who sent the highest number of emails—Kathryn Betty* (n = 121), Rolf Bauer (n = 77), and Rince Plum (n = 61). It was not surprising that Kathryn Betty was the most active participant because she was the listserv moderator, and the other two participants were also moderators for other listservs.

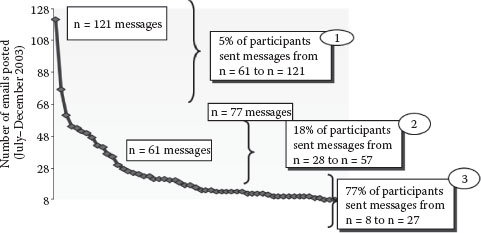

In a more detailed analysis, Figure 7.7 shows that the distribution of active participants fell into three groups. The first cluster of participants contained the three key people who were mentioned earlier in this section. These three made up only 5% of the total participants. Kathryn contributed 121 messages, an average of 20 messages each month, while Rolf contributed 77 messages, an average of 13 messages each month, and Rince contributed 61 messages, an average of 10 messages each month. The differences in number of messages sent were significant: between Kathryn and Rolf, a difference of 50 emails, while between Rolf and Rince, a difference of 15 emails.

The second cluster contained 18% of participants (n = 10), who posted from 28 to 57 messages; the difference in number of emails sent by each of them was not significant, a difference of only one or two emails. The last cluster showed the largest proportion of the participants, 77%.

Table 7.3 Distribution of Active Participation from Civil Society Participants: July–December 2003

Pseudo-Names | No. of Mails | No. of Participants |

Kathryn Betty | 121 | 1 |

Rolf Bauer | 77 | 1 |

Rince Plum | 61 | 1 |

Amanda Diego | 54 | 1 |

Mariette Michel | 53 | 1 |

Ruben Gerald | 51 | 1 |

Blanche Baldemar | 50 | 1 |

Jaquelin Floss | 47 | 1 |

Benjamin Ines | 42 | 1 |

Allan Patrick | 41 | 1 |

Sandra Burkasa | 39 | 1 |

Vince Markow | 37 | 1 |

Fedrick Marlin | 30 | 1 |

Adrian Alfonso | 27 | 1 |

Percy Fernand | 26 | 1 |

Edul Zaki | 25 | 1 |

Gerard Grosvenor | 24 | 1 |

Samuel Charles, Renee Blusky | 23 | 2 |

James Grutan | 21 | 1 |

Wutz Kaiser | 22 | 1 |

Alim Baruki, Njemile | 20 | 4 |

Negas, Steven Osborne, Venda Busara Rick Weissmen | 19 | 1 |

Emilio Marco, Verner Vinson | 17 | 2 |

Kim Soon | 16 | 1 |

Anita Johnson, Timothy Rhodes, Yihong Chang | 14 | 3 |

Jihong Mun, Patrick Adler, Morty Bijou, Albert Jonathan, Ellen Carlson, David Betrand | 13 | 6 |

Vesa Parnella, Raymond Jacob, Jimmy Punnel, Denise Merraga | 12 | 4 |

Melanie Milagros | 11 | 1 |

Butler Parnell, Charlie Nahum, Daniella Freud, Dawana Franks, Hokaido Kanagam, Tina Numen, Rudelle Franzisca | 10 | 7 |

Nadim Salman, Crsytal Shaw, Rolan Kiefer | 9 | 3 |

Emma Joshua, Isuzuki Akito, Stanford James, Tamara Antonia | 8 | 4 |

Total | 1,351 | 57 |

Participants in this cluster sent 27 or fewer messages, an average of only 4.5 messages each month.

Figure 7.7 Distribution of active Civil Society members in virtual plenary listserv.

Distribution of Less Active Participants

There were 165 participants that were considered as less active participants. They sent less than the average number of emails, a range from one to seven emails. The total number of emails contributed by them (n = 409) accounted for only 23% of the total emails posted in the listserv. In spite of the low number of emails sent, 80 of them did actually contribute to the decision-making process ranging from 1 to 5 messages and a total of 187 messages. Again, this number is still lower than the representation of the total participants who participated in the virtual plenary listserv during WSIS Geneva.

During the WSIS, Civil Society participants made numerous and wide-ranging decisions either individually or collectively during their face-to-face meetings. This study’s findings suggest that a similar process took place in the globally distributed environment that is particularly focused on the WSIS Geneva. The following empirical model of decision-making process is a revised version of the initial framework (see Figure 7.1). As illustrated in Figure 7.8, the decision-making model was adapted from Adler (1997) and Kingdon (1995). The model clearly depicts the activities that took place over the six-month period in the virtual Civil Society plenary listserv. The study was initially set to understand a four-stage decision-making model (see Figure 7.1). However, based on the empirical data, the findings indicated a more complicated model in which the process that the Civil Society participants were engaged in was reduced to only three main stages. Each of the stages used a different name from the adapted models to reflect the exact activities that took place, which are (1) problem identification, (2) proposal making, and (3) solution. This dynamic process was supported by a fourth stage called responses and deliberation. This stage underpinned the other three activities because every response received was fed into the decision-making process until a viable solution was achieved. Although Adler and Kingdon had a sequential model, I found that Civil Society participants were engaged in a more dynamic and iterative process in which the responses and deliberation occurred continuously.

In the first stage, one or more participants would state a problem, followed by other participants responding to the problem by proposing solutions. Most of the time, participants came up with many ideas and suggestions on how to solve the problems faced or how to improve a draft document. At other times, participants simply acknowledged problems without offering any ideas or solutions—for example, “I do experience the same problem” or “I agree with your sentiment.” Under rare circumstances, a problem was immediately resolved because a leader took independent or unilateral actions without going through the proposal stage.

Figure 7.8 Empirical model of globally distributed Civil Society decision-making processes during WSIS Geneva.

For the second stage, once proposals were made by the participants, the proposals received reactions or feedback from other participants; sometimes, this generated more ideas and alternative solutions. If people were supportive of the proposed language in the draft document, then they would endorse the draft document. But, if some participants did not agree with the suggested proposals, then counterproposals would be presented in a search for more viable solutions. This stage was often a long process as participants took the time to really look at the document and then provide thoughtful suggestions on how to improve it. Sometimes, however, the process was shortened because the document needed to be finalized within time constraints. In this iterative process, the multitude of responses received eventually led to the best solution that participants could offer.

For the third stage, solution took one of two forms. When participants faced a problem, the solution took the form of actions to remedy the situations or issues faced. For example, participants requested and received answers that clarified their concerns, or action was taken by the authoritative people (like the bureau or secretariat) to provide facilities needed. Sometimes, alternative solutions were proposed when participants were not satisfied with the offered solution. If there is an agenda to be met, like providing comments to a draft document or selecting or nominating speakers, then a different set of solutions is achieved. For such agenda-driven issues, the solution came in the form of endorsements. The more and the faster endorsements were received, the easier for the Civil Society to reach consensus. For example, in the case of a speaker’s selection, participants went through many cycles of nomination and counternomination; the solution was achieved when the name of the speaker was finalized. In some cases, despite the participants’ best efforts, proposals were made, and suggestions were given, but no solution was achieved; the decision-making process failed.

The decision-making process that Civil Society participants engage in via globally distributed collaboration occurs at the individual level—between and among participating Civil Society participants. Thus, the first assumption was to examine the decision-making process based not on the cognitive level but rather on the interaction level. Another important assumption was that the process is mediated by the use of CMC (in this case, by email). The last assumption was that decision making is based on consensus and not unanimity. Consensus means that only the participants engaged or involved in the process need to agree to the propositions, whereas unanimity means all the Civil Society participants must agree regardless whether or not they are involved in the process. This was hard to achieve via the email participation of Civil Society in the WSIS. For a consensus, the involved participants must come forward and endorse the proposals being made.

In essence, I would like to make the distinction between those two concepts clearly because, in the context of Civil Society participation on the WSIS email lists, people voluntarily work on a draft of proposal documents and propositions, which may lead to various decision points during the interim face-to-face meetings leading up to the WSIS event. After proposals were made, participants were free to react to the propositions. Solutions and decisions were made when consensus was reached. (Only the people who had read and participated in the process needed to endorse or agree to it.) Decisions were not based on unanimity wherein all the participants registered on the email list would have been required to endorse the proposals, nor did the process include all the Civil Society organizations in the WSIS. The email list was used to get as much agreement as possible so that actions can be taken or draft documents can be shaped, but was not presumed or required to result in unanimity.

Adler, N.J. 1997. International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, 3rd ed. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western.

Kingdon, J.W. 1995. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York: Addison-Wesley Longman.

Saaty, T.L. 2012. Decision Making for Leaders: The Analytic Hierarchy Process for Decisions in a Complex World. Pittsburgh, PA: RWS Publication.

* Only one participant did not continue to participate in the listserv from July onward.

* Please note that in order to protect the confidentiality of the participating Civil Society, all the names used in this study are fictitious names. Although the data were taken from a public email archival, an initiative was taken to create pseudo-names for all of the participants.