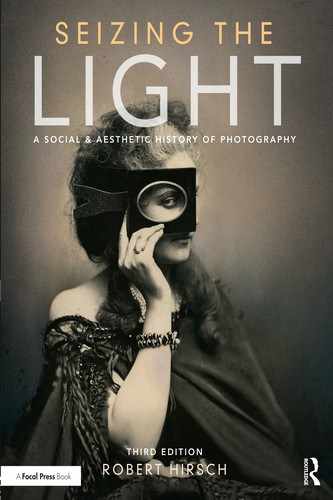

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Thinking About Photography

CONCEPTUAL ART: THE ACT OF CHOOSING

During the socially turbulent 1960s, artists rethought the roles of photographers, photographs, and viewers. Their practice shifted from Modernistic formalism that emphasized compositional and tonal elements of the straight print to a conceptual approach in which ideas took precedence over how subjects were depicted. By rejecting the premise that art had to have a tangible and aesthetic form, conceptual artists argued that process was equally valid as an artistic statement. Also, conceptual art offered a way to circumvent commercialization and formalism and supply a concrete framework for cerebral works of art. Conceptual artists adopted photographs, undervalued by the art establishment, as organizing mechanisms for transmitting cultural messages. Applying aspects of semiotics, feminism, and popular culture, many conceptual artists used the camera as an allegedly neutral recording device. They made deadpan prints that appeared to be aesthetically artless and that bore little resemblance to traditional fine art objects.

At its best conceptual art opened up possibilities of making art in nontraditional ways. An artist no longer had to be defined by their medium: one could talk, one could write, or one could make a photograph.

Conceptual artists and collaborative networks like Fluxus, which included Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), George Maciunas (1931–1978) Nam June Paik (1932–2006), and Yoko Ono (b. 1933), echoed the Dada movement and upset bourgeois expectations by choosing anti-rational intellectual and social concerns over sanctified aesthetic and visual ones (see Chapter 17, Artists’ Books). Although Fluxus had a foothold in mainstream culture, their agenda sought to revamp it. Their revolutionary manifesto called for a “living art” that that would purge contemporary work of imitation, illusion, and abstraction and would be accessible to more people, not just the art-world elite. They argued that an artist’s role is to enable people to see things differently, thus changing their values and vision over time. Mixed media events were their forte, exemplified by the Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik collaboration featuring Moorman playing her cello while wearing miniature television sets fashioned into a brassiere.

By combining filmic images and performance- based installations, artists such as Hollis Frampton (1936–1984), Yvonne Rainer (b. 1934), and Bill Viola (b. 1951) formed new hybrid platforms for making and viewing work, and such combinations and platforms would become hallmarks of contemporary digital media.1 Frampton also pioneered work in xerography (aka Copy Art) in the late 1970s and early 1980s after the introduction of the Xerox 6500 color copier in 1973, a machine that weighed 1,040 pounds. This reflected his thinking about photography as a democratic medium, and about how art should be made widely available, all of which led him to edition such works.2 This embrace of xerography also altered the traditional photographic process of imagemakers bringing their cameras to the subject matter. Now imagemakers could reverse course and bring their subject matter to the camera at a copy center where a trained operator ran the machine. This shift converted a normally solitary activity into one of artistic collaboration and information sharing. Along with its immediacy and low cost, this new “immovable camera” became a fresh photographic tool that fostered artistic communities capable of bypassing the conventional means of artistic education, production, censorship, and circulation. This sort of collaboration played off the notions of artist collectives that continue on today.3

© PETER MOORE. Charlotte Moorman wearing Nam June Paik’s TV Bra for Living Sculpture, 1969. Variable dimensions. Gelatin silver print.

The appearance of Nam June Paik’s name in the author’s position in this caption for a photograph by Peter Moore (a comparatively unknown artist) demonstrates some of the shifts that occurred during this time period. Paik’s work, in this case, as in many Fluxus-related works, existed only for a brief time during the date of the actual performance. Yet, we can study such performances today mostly through photographs and films that other artists, like Peter Moore, created as “documents’ of those events.

© Barbara Moore/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Mail art and rubber stamp art presented other egalitarian, nonconformist, low-cost Fluxus activities. Collagist and correspondence artist Raymond Edward “Ray” Johnson (1927–1995) became the founder of mail art with his New York Correspondence School project that gained traction in the 1960s and that continues on today. In mail art, the pieces were addressed, stamped, and mailed to the exhibition site. Shows were often loosely organized around a theme, and all works received got displayed. In rubber stamp art an image and/or text applied to inexpensive rubber stamps can be quickly reproduced endlessly, anytime, anywhere. Both were open democratic approaches that did not require high levels of technical skill. These techniques rejected the requirements that expert curators organize a show and that art should embody something original, precious, and irreplaceable.

Along with the practitioners of pop art, many artists and critics explored semiotics, the study of the signs that constitute the basis for all forms of communication (see Chapter 17).4 During the 1970s, certain artists used the analytical tools of semiotics to examine clichés, myths, and stereotypes about gender and power that were communicated and reinforced through mass-media sign systems. They incorporated semiotics-based analyses to try and reveal the multitude of possible meanings produced by the variations between the apparent, professed content of a work of art (what semoticians call the “text”) and the cultural assumptions of viewers. This approach disclosed both the social context for the production, reception, and dissemination of images and how this process shapes the underlying message of all representations.

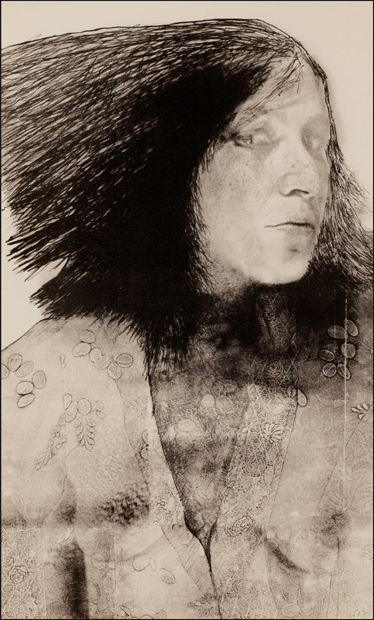

JOAN LYONS. Womens’s Portrait Series, 1971–80. 19 × 26 inches. Haloid-Xerox transfer drawing and lithograph.

Lyons tells us: “Through an investigation of the cultural feminine and female archetypes, I thought I might learn something about historical images of women. These are multiple transfers on large sheets of paper—a reconstruction by piecework. The medium is Haloid Xerox, the original view-camera based flatbed Xerox equipment that yielded a carbon image on plain paper—a photographic drawing.”5

John Baldessari’s (b. 1931) work of the late 1960s reconstituted the use of text onto canvas after reading Roland Barthes’s Mythologies (1957) in order to invest Barthes’s ideas about creating modern myths within mass media with new meanings. In 1968, Baldessari burned all his paintings as a means to break with technique and embrace the maxim that Art is truly in the idea (see Chapter 10). Such judgments, which form the core of the Conceptual Art Movement, led Baldessari to playfully commingle mediums. He courted ambiguity and the dualities of chaos and order and attempted to free himself from doing what artists had previously been expected to do: Organize the world and give it a defined, narrative meaning. During the 1970s, Baldessari asked himself “why photographers do one thing and painters another”. Baldessari answered:

The real reason I got deeply interested in photography was my sense of dissatisfaction with what I was seeing. I wanted to break down the rules of photography—the conventions. I began to say photographs are simply nothing but silver deposit on paper and paintings are nothing more than paint deposited on canvas, so what’s the big deal? Why should there be a separate kind of imagery for each?6

© JOHN BALDESSARI. An Eight-Sided Tale, detail from the Artist’s Book Close-Cropped Tales, 1980. 3⅝ × 6 inches (irregular shape). Photo offset.

COURTESY John Baldessari and CEPA Gallery, Buffalo, NY.

Baldessari appropriated and recycled images from mass media, especially Hollywood film stills, taking the existential position that choices make both your life and art authentic. His work is not grounded in formal issues but “is about the moment of decision and about fate intervening and chance eroding and disrupting our powers to make a decision.”7 In Close Crop Tales (1981), Baldessari rejected the rectangular picture format and broke away from formalistic confines of the edge by cutting his content-loaded images (film and publicity stills) into dynamic shapes with between three to eight sides.8 The book tells six “tales,” from “A Three-Sided Tale” to “An Eight-Sided Tale.” Baldessari explained:

it starts out a three-sided story and then all the images are three-sided, then four-sided, five-sided, six-sided—I think I got up to eight-sided images—and all the images are the different sides dictated by the internal composition, so there was a three-sided shape triangle, then there’s something in there [the pictures] that dictates those three sides. … All of the framing is dictated by what is inside.9

Today Baldessari employs assistants to help create his works, with mural-sized printing and framing “jobbed out” elsewhere. He sums up his outlook by explaining, “It’s delegation. An architect is a classic example. He doesn’t have to build a house. A composer doesn’t always have to conduct his work so why should an artist?”10

In Blasted Allegories (1978), Baldessari invited friends to ascribe a single word to black-and-white images randomly taken from television. Baldessari then arbitrarily colored or shaded each image with a hue whose first letter started with the same first letter as the chosen word. Algebraic messages were then added to the pieces to form verbal and visual “sentences.” This mutual exchange of visual and verbal groupings encouraged an open, multiple “reading” of the works. The dense, layered quality of allegory replaced the homogeneity of the metaphoric modernist approach.

Allegory, the reliance on symbols to represent meanings other than those indicated on the surface, was resurrected in the late 1950s by the French situationists. The situationists, characterized by Guy Debord’s (1931–1994) theories in Society of the Spectacle (1967) about commodity fetishism and mass media, proposed that transient experiences, like taking on the role of flaneur and strolling through a city, furnished fleeting sights and sounds that were themselves art. Their stance implied an end to art objects, and was based on a society so attuned to the aesthetic qualities of its everyday surroundings that people no longer required art. Other readers interpret this idea in a much more pessimistic fashion wherein everything is rendered into a “spectacle” for the masses, whose actual social life has be substituted with its representation able to be absorbed in a state of unthinking appreciation.

Allegory permits artists to deal with appropriation, fragmentation, transience, the disintegration of tangible means of measurement, and the uncertainty of meaning and time, while emphasizing content over pictorial concerns. Questioning a work’s source, purpose, context, audience, and significance disturbs the importance typically given to an artist as a shaman who can see and explain the world, suggesting a more equal and open-ended exchange between artists and audiences, encouraging viewers to ascribe their own meanings.

As approaches to photography became more cerebral, photographers searched for fresh models. Conceptual work dispensed with the modernist physical standards of the fine print—the thoughtful use of light, material, process, and technique—dismissing the bedrock upon which photography had gained its artistic acceptance. Sharing the character and outlook of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades (see Chapter 10), conceptual images blatantly ignore past aesthetics and heroic subject matter in favor of flatly describing mundane facts. Unlike documentary artists, conceptual artists recorded arranged events with a minimalist severity that abolished any visual components included solely for the sake of beauty. This reductionist outlook shaved subjects down to fundamental abstract ideas, often too complex to be understood within the confines of a single photograph, further challenging the reportorial mode of photography. Artists not absorbed in the observation of outer reality or their own personal lives abandoned the photographic method of making selections from the external world. These artists ceased acting as spectators and editors and instead took directorial responsibility for constructing images in their studios and darkrooms. The studio, instead of the street, became a creation site, recasting the nineteenth-century compositional syntax of Oscar G. Rejlander and Henry Peach Robinson, which had been exiled by Modernism.11 This way of thinking put photographers on an equal footing with other artists who had the authority to fashion images based on their internal directives. No longer was a photographer limited to picturing only what was visible, to being a presenter of physical evidence, and a reliable witness of outer reality, a reporter subject to the whims of available light. Ironically, freed of the documentary task from which photography had liberated painting, a photographer could now take the privileged position of creating what had formerly been considered an “unphotographable” internal event.

PERFORMANCE ART

French artist Yves Klein (1928–1962), a harbinger of Minimalism and Pop art, pioneered performance art when he “signed” the sky above Nice in 1947, in an attempt to grasp the immaterial. This term, “performance art,” has been retroactively applied to early live-art forms, such as body art and happenings. The progressive disintegration of conventional artist’s materials and presentation forms led to the engagement of the real body as a forum for cultural critiques as seen in work of artists such as Carolee Schneemann (b. 1939), Vito Acconci (b. 1940), Bruce Nauman (b. 1941), Marina Abramović (b. 1946), and Chris Burden (1946–2015). Performance art is an open-ended classification for art activities that include elements of dance, music, poetry, theater, and video, presented before a live audience and usually “saved” by photographic methods and shown to larger audiences. One of its purposes is to provide a more interactive experience between artists and audiences. All of the above artists have made use of the supposed objectivity of the photograph to give a documentary look to their arranged situations. For example, Klein’s Leap into the Void (1960) presents a photograph that appears to show him jumping off a wall, arms outstretched, and flying. Actually, the picture was a photomontage that eliminated the tarp Klein landed on for the final image. To complete the illusion that he was capable of flight, Klein distributed a fake broadsheet at Parisian newsstands commemorating the event. Numerous interpretations of this piece can grab one’s attention and imagination, but its affect and effect relies upon a viewer’s belief in photographic veracity. Klein juxtaposes irrational defiance against predictable expectations in an emblematic jump of self-discovery into the unknown.

© YVES KLEIN. Leap into the Void, 1960. Variable dimensions. Gelatin silver print.

COURTESY ADAGP, Paris; Photo: Shunk-Kender © Roy Lichtenstein Foundation.

© BRUCE NAUMAN. Portrait of the Artist as a Fountain, 1966. 19⅞ × 23¾ inches. Chromogenic color print.

In Portrait of the Artist as a Fountain, the half-naked Bruce Nauman first elevated his body to the status of a traditional sculptural motif (this work references Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), a urinal signed and exhibited as art). By spewing liquid, Nauman mimics urination and/or ejaculation, demoting the functions of his mouth from the intellectual process of speech to the physical process of elimination.

© 2016 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY. COURTESY Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York.

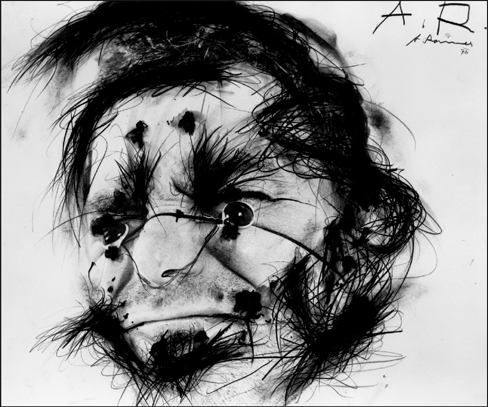

© ARNULF RAINER. Bundle in Face, 1974. 20-1/16 × 23-13/16 inches. Gelatin silver print with ink and oil crayon.

Rainer photographed himself grimacing to access a preverbal body language, but he felt the resulting images did not capture the psychic reality of his self-transformation. By uniting his photography and drawing, Rainer created a tension between the comic and the tragic in which “all sorts of new personages suddenly appeared to me who, all being ME, were not capable of manifesting themselves solely by the movement of my muscles.”12

COURTESY San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Austrian artist Arnulf Rainer’s (b. 1929) body became an innovative site for merging the historical pain and suffering of World War II with the fierce gestural marking or defacing of the print surface. Rainer thereby violated modernist tenets about the separation of art and photography by expressionistically exploring the “internal” human being, the soul, the power of instincts, and the subconscious.

William Wegman (b. 1943) wittily incorporated his dog, Man Ray (1970–82), into real-time videos that built upon the repetition of observing and recording numerous staged situations. In 1978, Wegman shifted his modus operandi from these spare studio video performances (a stream of moments) to the large-format Polaroid camera (a formalized controlled moment). This transformed the way Wegman worked and led to Man’s Best Friend (1982), the first of numerous publishing ventures in which his dogs appeared. Wegman’s dogs (Fay Ray followed Man Ray, and Wegman now works with her offspring) became “blackboards of living art materials” that Wegman nursed “into engagements not of their own thinking that are disturbing and funny … [while] being careful not to make them ridiculous.”13 By combining body and performance art, substituting a canine for familiar people and situations, Wegman systematically explored the metamorphosis of a single subject. Mixing detachment and love, Wegman cultivated his fantasies with a patient, “neutral” companion who takes all the transformations seriously.

© WILLIAM WEGMAN. Ray and Mrs. Lubner in Bed Watching TV (second version), 1981. 24 × 20 inches. Diffusion transfer print (Polaroid).

COURTESY Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York.

A RETURN TO TYPOLOGIES

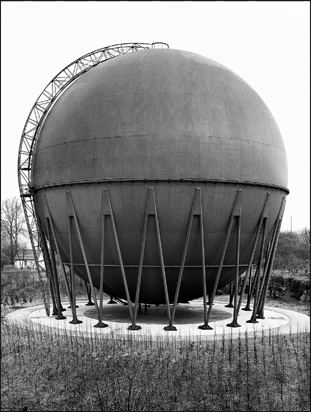

Bernd (1931–2007) and Hilla Becher (1934–2015) began collaborating in the late 1950s to document archaic industrial structures as archetypes, the paradigm of a class of subjects that represents the essential elements shared by all varieties of that class. Their dispassionate and highly ordered scrutiny favored a centered, frontal confrontation, utilizing a high point of view printed only in black-and-white. Backgrounds were minimized, eliminating the surroundings and diminishing perspectival depth. The overcast light was direct, flat, and lacking in differentiation. With no shadows, clouds, or traces of human activity, absolute stillness prevails. These artifacts, which the Bechers referred to as “anonymous sculptures,” expanded the Duchampian concept of the readymade and were based on an industrial archeology whose topology can be studied in a new setting without nostalgia and in whose configuration lies the microcosm of an ideal universe. The Bechers’ stated purpose is “to collect the information in the simplest form, to disregard unimportant differences and to give a clearer understanding of the structures.”14 Their deadpan, melancholic images form a comparative anatomy of vanishing architectural structures, which provides a system of understanding the world that cannot be achieved in a natural setting. However, critic Hilton Kramer wrote that the Becher’s photographs “look like the sort of pictures one sees in a real estate office.”15

The Bechers’ methodology renews the positivist, encyclopedic compulsion to catalog the world in the belief that to know something is to subdivide, quantify, and recombine it. Their work asks the “how” question without getting entangled in the thorny thicket of “why.” It disregards the issue of whether compiling more information always leads to a greater understanding of a subject. What is important lies in observing, measuring, and making conclusions based on the data, even if the subject of the data gathering cannot be explained. It is a way of distancing oneself through the act of presenting the world (in the Bechers’ case, industrial architecture) as an abstraction, moving observers toward the Elizabethan philosopher Francis Bacon’s proclaimed goal of science: mastery over one’s environment. Bacon’s Cartesian model equates truth with utility and the intentional manipulation of the environment. It considers the neoplatonist outlook that sees the universe as a holistic, living, interconnected organism, as mystical fluff. The Bechers thereby direct a course towards the domination of nature through a rational, technologically based thought process.16 This level of ambivalent and unsentimental detachment may prompt viewers to examine the relationship of these photographs to the amoral historical events of Nazi Germany, organized actions that affected artists of the Bechers’ generation. Does the Bechers’ conceptual stance come from a minimalist disposition or is it indicative of a larger consciousness defined by its refusal or desire not to examine its own totalitarian history that embraced dystopian catastrophe and ecological destruction?

The Bechers generally present their highly controlled photographs in a grid format (often about 3 × 3 feet). The image clarity allows the nuances of these functionalist sculptural compositions, many of which were about to be destroyed as obsolete when the Bechers photographed them, to be comprehended and appreciated. By objectively and collectively “naming” the subjects, the Bechers hoped to convey the pathos of their historical condition within a rapidly shifting industrialized culture.

As a teacher, Bernd Becher’s conceptual approach, treading between order and disorder, shaped the work of his students, including Candida Höfer (b. 1944), Thomas Struth (b. 1954), Andreas Gursky (b. 1955), and Thomas Ruff (b. 1958). Höfer’s large-format photographs of empty interiors and social spaces capture the “psychology of social architecture.” Ruff and Struth’s images emphasize an empirical formula of amassing facts to study in a judicious and systematic fashion. Ruff ’s larger-than-life-size, emotionally expressionless headshots serve as archetypes too, presenting a human head as a summary of the universe. His more recent building portraits are likewise serial and reclusive in nature, and have been edited digitally to remove obstructing details, giving the images a standardized appearance. Struth’s desire to reduce his visual vocabulary to its simplest premise—to look, to see, and to reflect—can be seen in his 12 × 16-foot Video Portraits (1996–2002). Here Struth shows with restraint the heads and shoulders of people calmly gazing into the camera, and by extension, at us. Except for occasional blinks, and small, involuntary muscular movements and other initially imperceptible occurrences, the steady and unmoving portraits combine the contemplative stasis of painting with photography’s grasp of the ephemerality of everyday occurrences.

© BERND and HILLA BECHER. Gasometer, Wuppertal, Germany, 1963. Gelatin silver print.

COURTESY Sonnabend Gallery, New York.

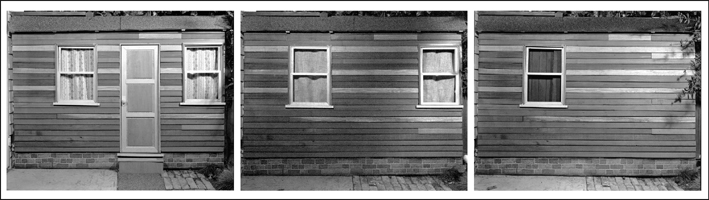

© ROBERT CUMMING. Three Sides of a Small House, the Fourth Being Obscured by a Low Wall and Some Foliage, 1974. 6¼ × 8 inches each. Gelatin silver prints.

Cumming sums up the underlying themes of his images as “out-and-out illusionism and magic tricks, satires, on the misreading of natural phenomena, and sardonic commentaries on the history or art and photography.”17

Licensed by Artists Rights Society/ARS, New York, NY.

Robert Cumming’s (b. 1943) analytical photographs emerge from scientific procedures for gathering evidence that stress objective measurement, controlled procedure, and technological methods. Cumming’s images run contrary to fine art expectations of personal expression, and they seem to rely on the photographic process to gather, organize, and document data into logical information. However, his work does not really do this. The images are pseudo-events, astutely staged, droll fictions that distort assumptions surrounding photographic veracity. Cumming’s meticulous “anti-documents” parody scientific correctness. Their purpose is not to dupe people—Cumming provides clues—but to challenge observers to find the defects in the visual logic. In the series Three Sides of a Small House, the Fourth Being Obscured by a Low Wall and Some Foliage, an attentive onlooker will notice that the side walls of the house are identical. Cumming’s visual record of this event is so minimal that it steers viewers into considering the ideas that constitute the event; in this case, the fictional nature of the subject becomes apparent, revealing how a photographer can contrive information. As he points out how the act of observation alters what is being observed, Cumming also questions photography’s impartiality and the role of the camera as a recorder and formulator of reality. His tableaux, reflecting his interest in Hollywood moviemaking, caution us to beware of messages delivered on a screen, whether TV, film, or computer.

The obsession with cataloging pushes its conceptual limits with Douglas Huebler’s (1924–1997) proposal to photograph “the existence of everyone alive in order to produce the most authentic and inclusive representation of the human species ….”18 Instead of creating aesthetically pleasing objects, Huebler coopted the objective repeatability of photography as a thinking aid to call attention to his larger conceptual goals. In this case, Huebler wanted to demonstrate the notion of impossibility. His utterly banal images challenged the idea that a single picture could explain any subject, and therefore they denied the significance of visual documents all together. In this way Huebler pointed out the deceptive rationalism that goes into the making of any photographic archive.

POSTMODERNISM

Postmodernism refers in part to the dissolution of traditional boundaries between art, architecture, popular culture, and the media. “It is part of a shakeup,” as Leo Steinberg famously argued, “which contaminates all purified categories.”19 This shakeup was accomplished by means of an open-ended process of borrowing and mixing ideas, art forms, and representations from the past and the present. As differences between mediums become less distinct, their unique concepts and processes commingle. This has led to the formation of ambiguous and contrary hybrids that pay no attention to the modernist concept of achieving “pure” articulated ways of thinking, making, and understanding the arts.20 Postmodernist theoreticians draw heavily from structuralist and post-structuralist theory. The structuralists believe meaning cannot be determined by surface appearances since everything from a photograph to a television program is a text that must be decoded.21 The post-structuralists then moved beyond the act of deciphering the “text” and unveiling the hidden assumptions behind it into what Jacques Derrida (1930–2004) called deconstruction. With deconstruction, Derrida believed that all meaning is fluid and temporary and there is no such thing as an underlying or absolute meaning. He and other post-structuralists conclude that finding true meaning is like trying to find your true reflection in a hall of mirrors. Everything is distorted.22 The notion that there is not a single truth of experience is at the core of postmodern thinking. This is in direct opposition to the modernist view of trying to discover the essential meaning in the world. Postmodernism has disallowed the notion of artistic intention, reference, and meaning and has led some critics to say it has cut off art from its political and social moorings. It has also encouraged artists to explore divergent ways of representing reality and reintroduced and reinvigorated issues from the 1960s like feminism, racism, and sexual orientation, and brought them to the forefront.

For postmodern thinkers, photography is not the stimulus for theory but the consequence of it. Jean Baudrillard (1929–2007) wrote that we are a media saturated society of the simulacrum, a “copy” for which there is no original. From his viewpoint, we are a culture not just of the image, but one in which the image has replaced that which it supposedly represented. These phantom images, or simulacra, supplant reality and curtail our ability to make genuine responses to life.23 Originality, a building block of Modernism, is no longer viable, since everyone in the industrialized world is contaminated and/or contained by mass culture. Its indiscriminate effects render us incapable of originality, making recycled, secondhand imagery the clear choice.

Since 1964 Gerhard Richter (b. 1932) has amassed “found” (discarded and lost) photographs and self-produced photographic documentation, including newspaper reproductions, prints, and snapshots, which he then preserves on panels. This endeavor, called Atlas (1964 to present), now includes thousands of photographic images on hundreds of panels, and serves as a way to “get a handle on the flood of pictures by creating order since there are no individual pictures at all anymore.”24 Richter’s penchant to build onto and produce new layers of meaning is also visible in the components of his “photo-paintings.” This series forges a relationship between painting and photography as it blends the past and the present, allowing a broader range of interpretation as the image shifts back and forth between abstraction and figuration. While suppressing detail, the blur frees the image from its moorings. This can inspire a viewer’s imagination to take on a photograph’s mutability at the juncture between obscurity and clarification, showing it is possible to see many more things in an ambiguous, less defined image than in one that is sharply focused.25

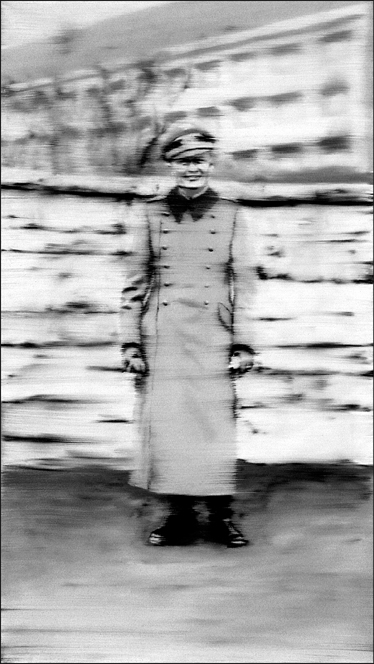

Uncle Rudi (1965) is modeled on a family snapshot, taken twenty-five years earlier, of the artist’s Nazi uncle proudly dressed in his SS uniform. Richter disrupts the photorealism that dominates Rudi’s “we will conquer the world attitude” by using a dry brush (he would later use a squeegee) to blur the carefully applied layers of paint, thereby canceling the reality within the portrait that fails to show the wickedness hiding behind a smile. Richter thereby points out how meaning cannot be contained, as it is contingent on our lived experiences. In his Uncle Rudi portrait, based on a photograph of a young man from a Richter family album who would die fighting for the Nazis, Richter plays off his Soviet Social Realism training that praises the heroism of communist workers and his later influence of capitalism’s utilization of advertising and popular culture imagery to assert the benefits of material wealth. Whether it is the Nazis, the Soviets, or the West, Richter’s contested space of multiple juxtapositions lets us see what fits our ideological predisposition, making the notion of a purely nonrepresentational image an unfeasible dream, confirming an image is never what it seems, only what we read into it.

© GERHARD RICHTER. Uncle Rudi (Onkel Rudi), 1965. 34¼ × 19 11/16 inches. Oil on canvas.

COURTESY The Czech Museum of Fine Arts, Prague, Czech Republic and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Some have argued that only those who directly experienced the Holocaust have the ability to truly represent it. Others disagree, claiming that the aftershocks of this calumnious event, and by extension other such occurrences, continue to vibrate so intensely that anyone who feels its effects has the right to try and find new ways of representing and understanding such trauma. These conceptual interpretations can be seen in the work of Christian Boltanski (b. 1944). Through the first-hand presentation of a historical event that does not rely on the traditional documentary formula of being an on-the-spot witness, narrator, or photographer, each artist demonstrates what Ernst van Alphen calls the “Holocaust effect.”26 Forgoing irony, Boltanski uses postmodern and “postmemory” methods to engage the past through indirect references about the unknown dead of the Holocaust by enlisting its signifiers, such as archival boxes, deteriorated snapshots, light bulbs, and piles of clothes.27 These items establish a theatrical environment that rescues and transforms the existence of ordinary people from the oblivion of war and time. His unsentimental process encourages viewers to reflect upon how this tragic event continues to haunt Western culture and its political policies throughout the world, and reminds us to be on guard against what Holocaust survivor and author of Night (1958) Elie Wiesel calls the “Perils of Indifference.”

© CHRISTIAN BOLTANSKI. Autel Chases (Altar to the Chases high school), 1987. “Lessons of Darkness,” installation view.

Boltanski reflects on his Holocaust work: “The act of naming is incredibly important. When you name someone you are saying—this person existed. I think one of the reasons I am so drawn to this idea is because the Holocaust is death without a trace. Nameless. Without a tomb.”28

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY/ADAGP, Paris.

COURTESY Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

Bart Parker (1934–2013), who studied with Harry Callahan, combined photographs and text to examine the separation between reality and the image of that reality. Parker asserted the primacy of the image by showing how a subject can be confused with its representation. Parker’s Tomatoe Picture (1977) evokes semiotic theory by directly comparing a subject with its sign: Two images, one made of an actual tomato and the second taken from a color photograph of a tomato, seem identical. However, the captions tell us that one image is of a “real” tomato while the other is a flat representation, making visible the postmodernist belief that representation (or at least photographic representation) misconstrues the original.

Over the course of a year in 1976–77, Paul Berger (b. 1948) photographed diagrams and formulas on classroom blackboards, only partially advancing the film after each exposure. Berger cut the developed film into thirds and contact printed it, and the continuously overlapping sequence of image strips created an abstracted progressive grid. The repetition of chalk lines in this series, entitled Mathematics, takes on a calligraphic flow, employing photographic accuracy to transform scientific information into a study about photographic representation, scale, space, and time. The fact that Berger spent a year making photographs of chalk lines also reveals the growing artistic disenchantment with “the subject.” If one accepts the postmodern notion that there is no “original,” it is easy to believe that the subject of one’s work is of little consequence. This acceptance of secondhand experience that denies the possibility of an original parallels the ideas in Barthes’s 1967 essay “Death of the Author” and in scholar Frederic Jameson’s pronouncements about the “death of the subject.” Post-structuralists would say that this position is an indication that the construct of the self never has existed and never can exist.29 Berger’s Seattle Subtext (1984) draws on these semiotic studies, using electronically transmitted imagery to comment on the mechanisms from which we obtain knowledge by reading photographs. Berger examines the collision between reality and illusion that occurs in viewer expectations when the changeable, electronic, digital mentality confronts that of the fixed, mechanical Gutenberg press.

The artistic collaboration known as MANUAL was formed in 1974 by Suzanne Bloom (b. 1943) and Ed Hill (b. 1935). Their choice of name implies a common guiding handbook as well as the sense of touch, reflecting their concerns about the phenomenological aspects of artmaking: observable facts and occurrences. MANUAL became an early adopter of electronic imaging to merge pictures/identities of the past with those of the present, atomizing time and space, leaving its audience with only the now. Their digital strategy implies that originality is a myth and that there can be no divine architect of creativity, or the true self, because everything inside a person’s mind has been imprinted by culture and language, inescapably making all images and texts reworkings of existing works; not even a photographer can reveal anything truly new.30

Victor Burgin’s (b. 1941) work takes on the photographically fragmented nature of the postmodern environment. Burgin deals with all events and images as being equally encoded with meaning and readable, and then he weaves them into one seamless reality. Along with conceptual artist Hans Haacke (b. 1936), Burgin created forums to address political consciousness, forums designed to upset the modernist position of making aesthetic considerations a priority. In his book Thinking Photography (1982), Burgin called for a new interdisciplinary photography theory emphasizing the process of signification.31 Here the content of a photograph (a sign) can be interpreted as having a meaning that is something other than the subject itself, depending on the ideological framework of the person decoding the sign. In The End of Art Theory (1986), Burgin placed the visual arts in the context of contemporary cultural theory that embraces language and socio-economic issues. Burgin’s combinations of images and texts cut across advertising, film, painting, and photography to deconstruct the modes and means of symbolic representation.

THE PICTURES GENERATION

The previously discussed artistic, philosophical, and social conditions gave rise to a group of artists loosely categorized as the “Pictures” generation. They were named after an exhibition held at Artists Space in New York in 1977, and the title later expanded to “The Pictures Generation” after a much amplified exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2009.32 These artists arose during the 1970s and 1980s from two main bases: the founders of the Hallwalls gallery in Buffalo, NY, and the migration of students and faculty from the California Institute of the Arts to New York City. The appropriation of images and ideas from mass culture including advertising, movies, and television united their works. After Minimalism and Conceptual Art, the act of “re-presentation, not representation”33—how images that surround us can be recycled to craft new interpretations of the world and ourselves—seemed to be the most viable and perhaps the only creative option available. Over time, artists and writers not originally included in either “Pictures” exhibition have been included in this broad group.

DECONSTRUCTING MYTHS

Richard Prince (b. 1949) claims to unmask the schema of advertising imagery by rephotographing and cropping found magazine images. Prince’s position is one of exhaustion. The world has all the photographs it requires, he says, and there is no need to make new ones. Satisfied to cull material from the existing stockpile, Prince makes it clear that, “These pictures are more than available, and unless you’ve been living in an alley, inside an ash-can, wrapped up in a trash liner (with the cover closed), chances are better than ever, you’ve seen them too.”34 The postmodernists call this practice of using existing images appropriation; critics refer to it as piracy. Prince describes the postmodern condition in his writing, which features nameless characters (who serve as surrogates for the artist):

Magazines, movies, TV, and records…. It wasn’t everybody’s condition but to him it sometimes seemed like it was, and if it really wasn’t, that was alright, but it was going to be hard for him to connect with someone who passed themselves off as an example or a version of a life put together from reasonable matter…. His own desires had very little to do with what came from himself because what he put out (at least in part) had already been out. His way to make it new was make it again, and making it again was enough for him and certainly, personally speaking, almost him.35

Prince’s postmodern stance asserts that most people only know the world through secondhand experience, through copies. Thus, as the original disappears so does its mythic value, emphasizing the Duchampian act of choosing as the artistic action. His radical cropping and enlargement of details provide an avenue of inquiry into the media’s presentation of gender through posing and stereotype, although Prince never explicitly condemns such practices, thus raising thorny questions such as: Is what Prince is doing legal? Where is the boundary line between art and plagiarism? What does his work say about the changing nature of authorship?

Photographer Patrick Cariou sued Prince and the chic Gagosian Gallery in New York for copyright infringement, claiming that Prince plagiarized his Yes Rasta photographs in a series of paintings and collages, called Canal Zone (2007), and failed to “transform” the context of his original work. Prince countered, claiming “fair use,” and testifying that he “[doesn’t] have any really interest in what [another artist’s] original intent is because … what I do is I completely try to change it into something that’s completely different….”36 The court initially concluded that Prince and Gagosian had infringed on Cariou’s copyrights. Prince appealed and the ruling was largely reversed. Eventually, the parties settled the suit out of court.37

© RICHARD PRINCE. Untitled, 1987. 27 × 40 inches. Chromogenic color print.

COURTESY Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

To make his New Portraits series (2015), Prince took Instagram screen shots, had them enlarged, and sold them for $90,000 at the Gagosian Gallery. One woman whose picture Prince used has been selling photographs of Prince’s photograph of her original posting for $90 with the proceeds being donated to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit whose mission is protect digital content rights.

Sherrie Levine (b. 1947) took Prince’s concept even further by rephotographing a reproduction of Edward Weston’s Torso of Neil and exhibiting it as her own work, Untitled (After Edward Weston), in 1979. Levine did the same process with Walker Evans’s photographs, and later with reproductions of well-known paintings. Her actions bluntly condemn what she and other feminist artists consider a competitive, male-dominated, capitalist culture’s insistence on the importance of originality—on who did it first. After working as a commercial artist earlier in her career, Levine stated that she “was really interested in how they [the commercial art field] dealt with the idea of originality. If they wanted an image, they’d just take it. It was never an issue of morality; it was always an issue of utility.”38 Nonetheless, other critics argue that culture cannot be divorced from morality, that culture is selective, and that selection involves choices; these choices form the basis of our ethics. Levine’s apparent renouncing of the traditional meaning of authorship, creativity, and originality was (on one level) a rejection of the modernist belief in progressive change, which infuriated most viewers and foreshadowed numerous, ongoing ethical issues surrounding the digital appropriation of other artists’ works. Her copies of copies, functioning as stand-ins for the originals without the original artists’ agreement, amplified the inherent defects of the mechanical reproductions process. Levine stated:

The pictures I make are really ghosts of ghosts; their relationship to the original images is tertiary, i.e., three or four times removed…. I wanted to make a picture which contradicted itself.39

Levine’s “ghosts” reinforce Baudrillard’s position that power can be exercised through controlling the means of representation. By understanding the code in which the originals support biased cultural assumptions and stereotypes, and by reusing the images critically, one can deplete their power.

Mike Mandel (b. 1950) satirized and deconstructed expectations surrounding the American myth of fame. His photo-offset series, Baseball Photographer Trading Cards (1975), took a group of “photo stars” like Ansel Adams, dressed them up as baseball players, and anointed them with the visual status accorded to sports idols on collectable bubble gum trading cards. While normal baseball cards provide a player’s batting statistics, these cards listed items like the photographer’s favorite film and developer. These “clubby” cards pay ironic homage to a photo-elite unknown to the public at large. They indirectly ask why top artists do not receive the same status and financial rewards as celebrity sports figures, pointing out the value placed on artmaking. Later, Mandel teamed up with and Larry Sultan (1946–2009) and selected photographs from a multitude of found images that previously existed solely within the boundaries of the industrial, scientific, governmental and other institutional sources from which they were mined. The resulting project, Evidence (1975–77), became one of the first conceptual photographic works of the 1970s. Evidence demonstrated that the meaning of a photograph is conditioned by the context and sequence in which it is seen. Their results, both hilarious and perplexing, deliver an absurd and mindful take on the complexity that images possesses when viewed in isolation, outside their original contexts. Along with Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip (1973), Evidence is a precursor to postmodern photographic practices, opening new possibilities that have been explored by artists including Joachim Schmid, Cindy Sherman, and Carrie Mae Weems.

Joachim Schmid (b. 1955) is a photographic recycler who collects, studies, and organizes society’s photographic detritus—photo-based images he has found in flea markets or online from which he makes collections of repetitive imagery. Schmid curates these vernacular pictures into different categories of recurring themes, such as Airline Meals, Postcards, Sex, and Various Accidents. In a Duchampian manner, he self-published ninety-six of these groupings as art books that examine how our society delights in producing the same types of pictures over and over again, turning the complete set into a visual survey of twentieth-century snapshots. Based on his motto, “You can observe a lot by watching,” Schmid’s chaotic, multifaceted, and paradoxical project—which can be printed on demand via his website: https://otherpeoplesphotographs.wordpress.com—reflects the state of over production of both photographs and photographers. This hyper production has weaved photography ever deeper into our everyday experiences while simultaneously devaluing the makers and their output. This, in turn, adds another layer of difficulty for photographers who try to make a decent living from their creative works.

To facilitate his process, Schmid jokingly set up The Institute for the Reprocessing of Used Photographs in 1990 that offered to recycle “used, abandoned and unfashionable photographs… free of charge.”40 Much to his surprise, the “Institute” became overwhelmed with negatives and photographs, including a package that contained decades of medium format negatives that had been sliced in half from a professional photographic studio.

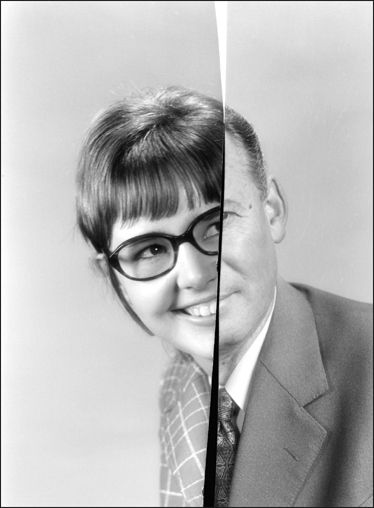

© JOACHIM SCHMID. Photogenetic Drafts, #4 1991. Variable dimensions.

Gelatin silver prints.

Since Schmid was not concerned with their commercial value, he repositioned the left half of a negative with the right half of another negative to produce new baffling composite portraits that were uniformly lit and matched together in unexpected ways. This worked because the studio never seemed to have changed the position of its lights nor did it move the camera, essentially making the exact same picture over and over again, which can be interpreted as a critique about photographic excess and the “creative” experience in terms of original authorship.

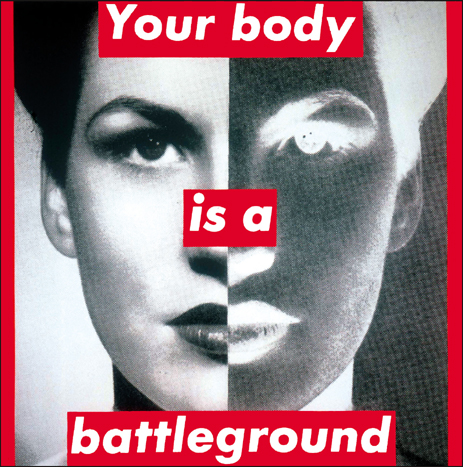

Barbara Kruger (b. 1945) spent ten years working as a graphic designer for various women’s magazines that extolled beauty, fashion, and heterosexual relationships before she began to produce photomontages, resembling billboards, with text that questioned capitalism’s relationship to patriarchal oppression and the role consumption plays within this social structure. In Remote Control: Power, Culture, and the World of Appearance (1994), Kruger deconstructs consumerism, the power of the media, and stereotypes of women to show how images and words manipulate and obscure meaning. Kruger states, “I work with pictures and words because they have the ability to determine who we are, what we want to be, and what we become.”41 One of Kruger’s montages literally asks the viewer: Who speaks? Who is silent? Who is seen? Who is ignored? Kruger visualizes what Roland Barthes called “the rhetoric of the image,” showing viewers the tactics by which photographs impose their messages, revealing the hidden ideological agendas of power.42 She sees stereotypes of women as instruments of social power, determining who is in and who is out of fashion and of society. Her curt phrases—“Who is bought and sold?” “Your manias become science,” “Your gaze hits the side of my face”—go to the core of male demonstrations of financial, physical, and sexual power.

Drawing on the seductive strategies of advertising, Kruger reuses anonymous commercial, studio-type images of purposely orchestrated movements. Like Prince, Kruger is not interested in action per se, but in “the stereotype’s transformation of action into gesture.”43 Her selective use of personal pronouns—I/my you/your—builds attraction, emphasis, and significance by simultaneously connecting the addressee and the speaker. Since English first- and second-person pronouns do not carry gender, they allow both male and female observers to enter into Kruger’s work and illuminate the mechanisms of involuntary subjection. Kruger also recognizes the changing usage and reality of a photographic message, and its frequently theorized connections with themes like death (à la Barthes), and she designs her work to function in numerous situations, including books, gallery walls, installation environments, and billboards. Kruger explains:

© BARBARA KRUGER. Untitled (Your body is a battleground), 1989. 112 × 112 inches.

Photographic silkscreen on vinyl.

Kruger asserted: “The thing that’s happening with photography today vis-à-vis computer imaging, vis-à-vis alteration, is that it no longer needs to be based on the real at all. I don’t want to get into jargon—let’s just say that photography to me no longer pertains to the rhetoric of realism; it pertains more perhaps to the rhetoric of the unreal rather than the real or of course the hyperreal.”44

The Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles, CA.

COURTESY Mary Boone Gallery, New York.

But to me the real power of photography is based in death: The fact that somehow it can enliven that which is not there in a kind of stultifyingly frightened way, because it seems to me that part of one’s life is made up of a constant confrontation with one’s own death. And I think that photography has really met its viewers with that reminder.45

FABRICATION

Instead of reusing existing images, James Welling (b. 1951) photographically converts household items into familiar, archetypal images: Crumpled aluminum foil becomes an apparent abstract landscape. Yet, expectations related to what viewers think they have seen and felt are left unfulfilled, setting up a contradictory mental state that promises emotion and insight but reveals only the materials that manufactured the scene. Welling’s synthetic landscapes personify the circumstances of postmodern representation: They simultaneously are about something particular, everything in general, and nothing whatsoever. In a process of circular meaning, the work embodies the postmodern concept that all representations refer only to other representations.

© CARL CHIARENZA. Untitled Triptych, 56/55/54, 1996. 5 × 11 feet. Gelatin silver prints.

Chiarenza states: “The problem is to get the viewer to release the commonly but falsely held belief in the photograph as a window; to get the viewer to go through the window in a state of openness to a new experience, not a representation of one that has already occurred.”46

Working in his studio, Carl Chiarenza (b. 1935) arranges scrap materials to make collages specifically to be photographed. In the tradition of Alfred Stieg-litz, Minor White, and Aaron Siskind, Chiarenza’s pensive symbols formulate a connection between the mind and nature that elicits inner emotional states. This work often references the landscape and it deconstructs formal media boundary lines and allows photography to merge with sculpture, graphic design, and painting. For Chiarenza photography is a process of transformation and, as such, he utilizes photography’s illusional qualities to remind viewers about the differences between a photograph and reality.

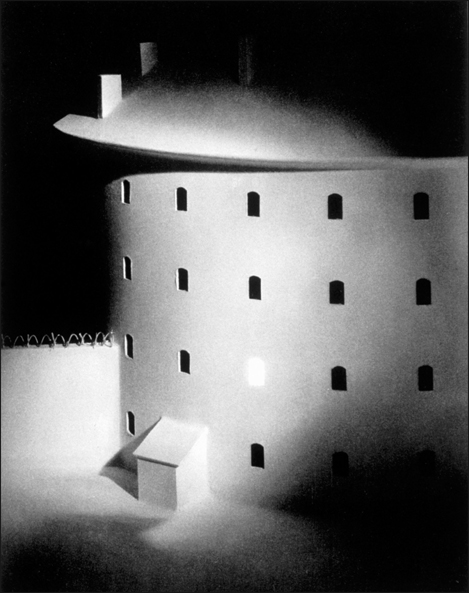

Artists such as Sarah Charlesworth (1947–2013) and James Casebere (b. 1953) manufactured stylized “signs” to present archetypal situations. Casebere’s In The Second Half of the Twentieth Century47 deploys his handcrafted miniatures along with text to examine the way society entrusts toys to encode cultural messages to children. The practice of building and photographing models allows artists to contemplate their subject by physically interacting with ‘them’ over a period of time. The models serve as abstract stand-ins for previous ways of representing the subject, prompting viewers to question how images become loaded with intentions and how this affects their own thoughts about the subject. Synthetic archetypes also permit artists to combine or incorporate subjects that do not physically exist, as in Casebere’s moody recreation of the prison of the Bastille. Such recreations play with notions of traditional photographic time by permitting pre-photographic subject matter to be fixed in photographic form.

© JAMES CASEBERE. Panopticon Prison #3, 1993. 22¾ × 25¾ inches. Waterless lithograph.

COURTESY Sean Kelly Gallery, New York.

Laurie Simmons (b. 1949) stages miniature figures and environments as stand-ins for suburban middle-class societal models and gender stereotypes. Her strategy, surrounding In and Around the Home (1983),48 often included a dollhouse, symbolizing the loss of childhood innocence, where small-scale figures reenact scenes of how society teaches women (and by default men) to behave. Her deployment of toy figures, puppets, ventriloquist’s dummies, and eventually real women portrayed as living dolls provide the necessary distancing for Simmons to scrutinize and disclose the patriarchal customs that express and teach our cultural behavior models. Dealing with similar themes, Ellen Brooks’s (b. 1946) tableaux incorporate miniature substitutes that displace the sentimental nostalgia of the dollhouse with a disquieting and trenchant milieu of sexual anxiety. Since 1972 David Levinthal (b. 1949) has been utilizing toys within dioramas to create mythological references to comment on American culture and historical events that appear in books including: Hitler Moves East (1977), The Wild West (1993), Baseball (2009) and History (2015).

© LAURIE SIMMONS. Woman Opening Refrigerator/Milk in the Middle, 1979. 6⅛ × 9½ inches. Chromogenic color print.

COURTESY Salon 94, New York.

Sandy Skoglund (b. 1946) makes room-sized installations of impossible situations in supersaturated, contrasting colors. Skogland often builds these sets to portray adult anxieties in childlike models and/or surreal confrontations between nature and culture, which she then photographs. Her mixture of sculpture and photography humorously expresses the continuing need artists have to be physically involved in the process of making objects. “Instead of taking everything out, like Minimalism did, I turned around and started to put everything back in,”49 said Skoglund. The emphasis remains on controlling the subject while creating juxtapositions normally unseen in nature that reveals the tensions between the internal and external worlds. Utilizing photography as a unifying container of meaning, Skoglund does not want to get caught up in making things look “natural” for the camera. She does not see fabrication as being cynical or out of touch with reality, but as a place where “the world of ideas and the world of appearances come together.”50 With that combination realized in her works, viewers might contemplate the connections between the natural and the man-made environments.

Olivia Parker’s (b. 1941) enigmatic still-life assemblages, featuring organic and inorganic subject matter such as flowers and maps, rely on a process of recon-textualization to achieve their “human implications.” Her juxtapositions, reverberating on the legacy of Cubism and Constructivism, describe a realm of interior spaces and inner states. Parker elegantly suggests themes, such as death, sensuality, and physical and spiritual travel, but she does not provide definitive meanings. A major focus of her work has been on how our understanding of the world has shifted and reshifted from alchemy and magic, to an empirical mechanical model, to a realm of theoretical mathematics (or chaos theory).51 Parker believes that part of being creative is the ability to dive off into the unknown. She asserts: “It’s not just the willingness to go off the edge; it’s the ability to move and act without knowing exactly what’s going to happen.”52

© SANDY SKOGLUND. Revenge of the Goldfish, 1981. 30 × 40 inches.

Dye-destruction print.

The studio tableaux combined with the legacy of surrealism in the work of Joel-Peter Witkin (b. 1939) upsets photography’s associations with the real. Witkin blends the erotic and the macabre in order to examine areas that are considered off-limits by society. His morbid Hieronymus Bosch-like scenes, replete with corpses, fetuses, and hermaphrodites, suggest that hell is a current state of being. Witkin compares his work with the last trial of St. Francis of Assisi, who confronted the demise of his own flesh by kissing a leper’s pus-filled lips and saw the leper turn into Christ. As with the writings of the Marquis de Sade, Witkin’s grotesque permutations of bestiality, crucifixion, and sadomasochism have a commanding physical appearance that allows us to see that beauty and evil are not always, or ever, mutually exclusive. Witkin tells us:

© JOEL-PETER WITKIN. Still Life, Marseilles, 1992. 26 × 32 inches. Toned gelatin silver print.

Witkin considers that: “When I’m working with a severed head, I’m engaged in very direct spiritual dialogue…. My job, given the opportunity, is to put flowers into the remainder of his brain, as if it were the well of my existence.”53

COURTESY Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, and Baudoin LeBon, Paris.

The Grotesque derives from grotto, the caverns and subterranean darkness. Saints loved the darkness because that’s where you go to bring out the people who are drowning. When I, as an individual, continue my journey into perception and better realities, I have to engage the person in darkness because I’m in darkness…. We all have to make a decision as to what we’re basically serving. If your life and work are about despair, there’s no resolution, no redemption.54

Witkin uses the darkroom to tamper with expectations about the imagery a photograph delivers and how a photograph looks. He often reinforces the brutality of his scenes by scratching the negative and staining and vignetting the print, giving us the feeling that his prints “were to be punished for the vision they carried.”55 Witkin also exposes areas of the print through tissue—flat, wrinkled, wet, or dry—for a selective visual softening, and he uses toners to produce a warm effect. These nonconformist methods, which some consider heretical for their unorthodox craftsmanship, provide an atmosphere of age, giving his prints an aura of authenticity and believability. Within the studio, Witkin conjures up artifice and reality, using historical art references to speculate on allegorical, conceptual, religious, and sexual potentialities.

© PATRICK NAGATANI and ANDRÉE TRACEY. Alamogordo Blues, 1986. 20 × 31 inches.

Diffusion transfer print.

Fabricating environments for the camera allowed the team of Patrick Nagatani (b. 1945) and Andrée Tracey (b. 1948) to densely pack symbols from popular culture into a controlled situation. The influence of movie special effects appears in their extensive sets and painted backdrops, which also recall Nagatani’s work as a Hollywood set painter. Their images contradict our expectations as the outer logic of photographic truth commingles with modern anxieties, allowing an interior landscape to come into view. Nagatani’s book Nuclear Enchantment (1991) employs similar strategies to metaphorically examine the histories and social issues surrounding America’s nuclear culture and the events that have shaped it, including the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

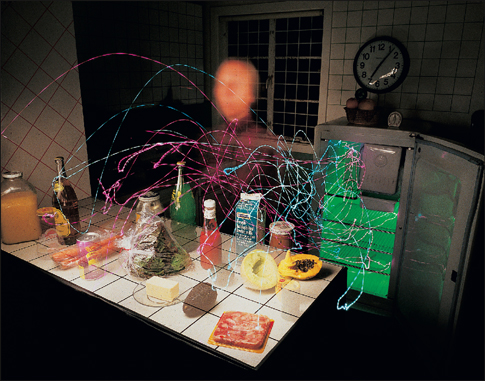

Philip-Lorca diCorcia (b. 1953), Gregory Crewd-son (b. 1962), and Jeff Wall (b. 1946) take a similar conceptual approach to scripting out their photographs. Staging his images for the camera, diCorcia has models perform familiar domestic scenes, like a man staring into an open refrigerator at night, in order to convey existential dread. Working with a film crew and combining multiple exposures, Crewdson builds pristine cinematic tableaux that depict the psychological pathos of a suburban America where people anxiously stare into space seemingly searching for something they have lost or have yet to find. Wall deals with metaphysical panic by digitally orchestrating elaborate and obsessive scenes, like Dead Troops Talk (1986), which meditates on anxiety, fear, and violence.

© JEFF WALL. Dead Troops Talk (A Vision after an Ambush of a Red Army Patrol, near Moqor, Afghanistan, Winter 1986), 1992. 90⅜ × 1643/16 inches. Transparency in a light box.

This scene, set up in a suburban Vancouver studio using a team of actors, some borrowed military garb and lots of fake blood, continues to reverberate in the West since the events of 91 1 and the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan by the United Stated and its allies with the still-ongoing war.

Such images challenge assumptions by asking: Is a constructed image innately less truthful than a decisive moment? Or, can an assembled picture reveal previously unseen truths? After all, both types of photographs assemble ambiguous facts and fictions camouflaged as truth in order to describe real situations; the constructed image merely defies the traditional photographic approach of grabbing the scene out of the flow of unstaged real time events. By skating the edge between life and theater these image-makers reveal certain veiled stories, mythic forms, and perplexing situations that also, in fact, make up our existence.

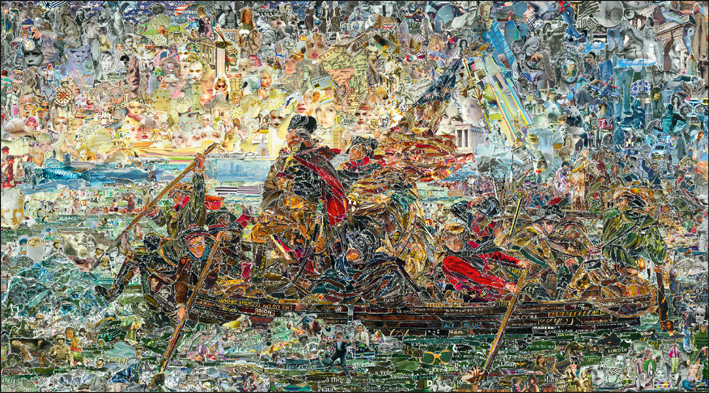

Vik Muniz (b. 1961 as Vicente José de Oliveira Muniz) energetically combines photography with other media to re-envision his subjects and promote looking with more attention. By working with unusual materials, such as chocolate, dust, garbage, ketchup, sewing thread, skywriting, sugar, and syrup, Muniz establishes original ways to visualize his subjects. “There’s no way to discover without being involved in the making of it,” says Muniz, “and through the process, you start to realize the mechanics of representation.”56 For instance, Muniz collected dust from the Whitney Museum of Art galleries that he then used to make drawings based on installation photographs of minimalist and post-minimalist art from the museum’s archives. He then photographed his dust drawings to generate representations of representations in order to confront the topic of originality and reproduction. Muniz’s images point out the contrivances for transmitting reality rather than an idea of reality itself. This reflects his belief that only after ridding itself of the responsibility of duplicating reality is it possible for art to have something to say This can be seen in his Pictures of Magazines series, where portraits and still lifes are constructed out of tiny pieces of circular colored paper, hole-punched from magazines and arranged like paint dabs to generate satisfying simulacrums. In his Pictures of Magazines 2, Muniz employs torn magazine images to construct re-renderings of paintings by Paul Cézanne, Vincent Van Gogh, Emanuel Leutze, and Édouard Manet, that he then photographs and enlarges into mural-sized prints. The eye continually vibrates when examining these works, focusing back and forth between the synthesized image and its composite parts, positing that there is no secure Truth, only fluid perception.

VIK MUNIZ. Washington Crossing the Delaware, After Emanuel Leutze, from the series Pictures of Magazines 2, 2012. 60 × 108¼ inches. Chromogenic color print.

Art © Vik Muniz/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

ALTERING TIME AND SPACE

Imagemakers like Jan Dibbets (b. 1941), Eve Sonneman (b. 1946), and Lew Thomas (b. 1932) investigated the cultural functions of photography as influenced by the sequential nature of film, by serial forms of minimal art, and by the use of language in conceptual art. Often working with multiple images and the stability of the grid pattern to ground their compositions, they expressed conceptualist concerns with real time, information systems, and theories of knowledge and process, and they challenged the notion of a singular, stable existence. Thomas would expose thirty-six frames of black-and-white 35mm film of a mundane subject, making only slight compositional changes in each frame, as in Time Equals 36 Exposures (1971), in which a GraLab darkroom clock is photographed 36 times as it is turning counter-clockwise. The resulting images were ordered into 48 × 96 inch grids, which further diminished the subject and forced a viewer’s attention to issues of time and space to examine the underlying structure of how an image is experienced.

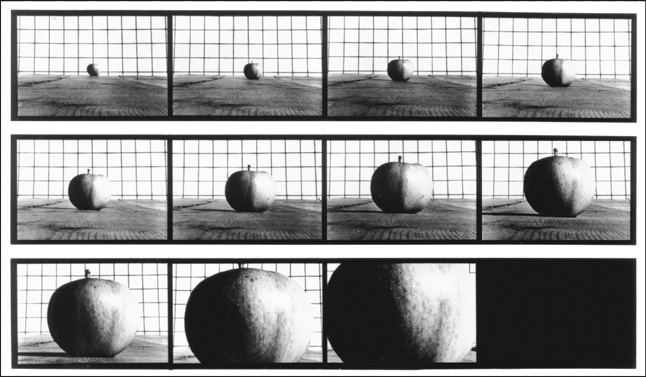

© HOLLIS FRAMPTON and MARION FALLER. Apple Advancing from the series Sixteen Studies from Vegetable iocomotion, 1975. 11 × 14 inches. Gelatin silver print.

The structuralist filmmaker Hollis Frampton (1936–1984) and Marion Faller (1941–2014) utilized adjoining 35mm frames to humorously explore real-time activity and pay homage to Eadweard Muybridge.57 In their Vegetable Locomotion series the grid is deployed to lend the appearance of empirical science. Mike Mandel carries on a similarly satirical critique in Making GoodTime (1989), applying early twentieth-century beliefs about how to scientifically manage time/space reality to the domestic middle-class culture of southern California. Mandel’s tableaux, based on the Gilbreths’ work (see Chapter 10), reveal the limited nature of photographically portrayed time and deconstruct the supposed model of reality that it assembles. Christian Marclay’s (b. 1955) The Clock (2010), a looped 24-hour montage, edited from about 12,000 film and television clips, functions as a clock by interlacing timepieces, human actions, along with a synchronized soundtrack to simultaneously evoke Newton’s mathematical model of absolute time with Einstein’s theory of relativity and motion. Although their approaches were diverse, these artists all shared the desire to transform and expand the photographic experience as predicated on the supremacy of the single image of a moment in time. Their efforts at reimaging time and space helped to widen the discussion concerning the nature of photography.

Barbara Kasten’s (b. 1936) constructivist studio assemblages formally intermix color, line, perspective, texture, and volume to dissect hypothetically designed spaces into separate sectors. Her work seemed so in tune with postmodern architecture that Kasten left her studio to incorporate actual buildings as sites to “reorganize the visual environment.”58 Her large-scale, interdisciplinary productions were indicative of an era where photographers became scene builders, managing skilled crews to handle the lights, colored gels, mirrors, and scrims to alter our perception of how things appear by disorienting our customary sense of reflectiveness and transparency. But by recording everything in a single moment, with no multiple exposures or postcamera manipulations, Kasten re- and/or de-stabilizes the visual characteristics of light and mass, expressively asserting new possibilities within and beyond the familiar photographic realities.

© MIKE MANDEL. Emptying the Fridge, 1985. From Making Good Time, 1989. 20 × 24 inches.

Dye-destruction print.

The sanctity of the individual image was assailed by artist David Hockney (b. 1937) as he explored multifaceted representations of a subject. Dissatisfied with the way photography rendered depth and represented time and space, Hockney believed that people gave conventional photographs only a brief look because they lacked “lived time.” “Life is precisely what they don’t have … photography is all right if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralyzed Cyclops—for a split second.”59 Hockney expresses philosopher Henri Bergson’s idea that matter is in constant movement. One way to convey this reality is through a synthetic view of a subjective experience, an artist’s projection of self-awareness onto the external world. Hockney did this by making numerous photographs of a scene and arranging the resulting prints into a collage that navigates a dynamic interaction of motion, space, and time. His canvas-sized visions bring together an expanded collection of components observed over time and fabricated into a grand, extended, constantly changing entirety. By interrupting space and displacing time, Hockney broke the perspective of the Renaissance window, carrying his swaying synthetic images beyond the edges of the frame, dissolving the rectangle. Joyce Neimanas (b. 1944) did similar work, arranging Polaroid SX-70 prints, not to reproduce the scene as the camera may have seen it, but according to her own internal rules of perspective.

© DAVID HOCKNEY. Pearblossom Hwy., April 11–18, 1986 (2nd version). 78 × 111 inches. Chromogenic color prints.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

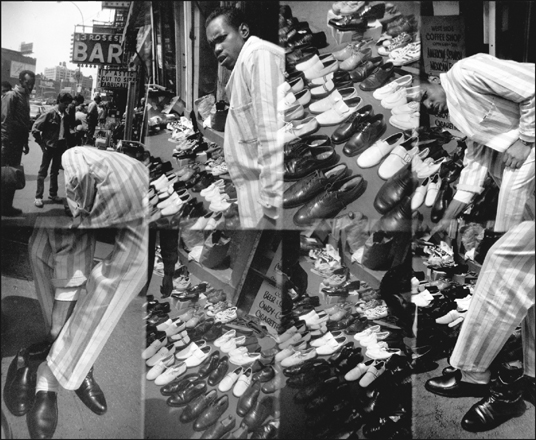

© MICHAEL SPANO. Untitled (Used Shoes), 1984. 46 × 55 inches. Gelatin silver print.

Spano builds postmodern associations by juxtaposing his subject(s) in space and time. The sequence camera allows Spano to physically move through a scene as each of the eight lenses exposes a different section of the film, creating an interval of time that is longer than a single instantaneous moment.

Michael Spano (b. 1949) operated a Graph-Check sequence camera to make a two-tiered grid of eight separate exposures onto a single piece of 4 × 5-inch film, reminiscent of the nineteenth-century carte de visite’s multi-lens cameras, as he actively moved the camera into and through a scene. The motion in his work dynamically visualizes the chaotic and frenzied nature of postmodern city life: subjects appear, disappear, reappear, and move about within a scene; Renaissance time and space collapses; ordinary transactions dissolve into uncommon incidents. The juxtaposition of images invites viewers to make fresh associations. As the narrative format dematerializes, a new perception comes into being, presenting the world in a state of multiplicity.

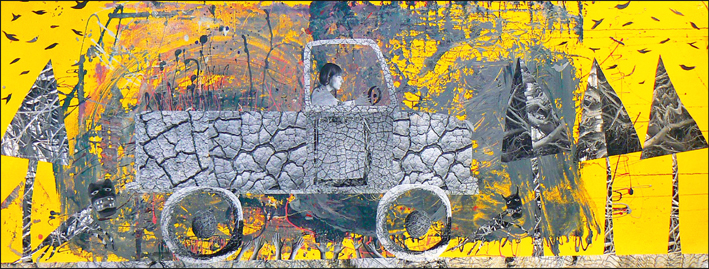

© HOLLY ROBERTS. Mud Truck, 2006. 30 × 80 inches. Mixed media.

Holly Roberts (b. 1951) lived in the Zuni Pueblo during the 1980s where she found that the Zuni belief in multiple realities— wherein a person might be transposed into an animal—reinforced her own intuitive beliefs. Roberts obliterates the mechanical photographic image with paint, opening a path that treads a line between mystery and realism and allowing visceral feelings to dominate the subject matter. Real world time is left behind as observers engage with the visual presence of an altered dreamlike state and the physicality of the pictures themselves, which meditate on cultural history, human emotions, the landscape, and interpersonal relationships. This permits Roberts to usurp the authenticity of the photographic rendition of reality and/or to oppose or parallel it with her painting. In addition to single images, Roberts also cut out portions of her photographs and mounted them together on canvas, permitting her to work on a larger scale, combine parts of different images, and obtain a richer intricacy of surface quality and texture. Roberts notes:

My unconscious intelligence directs my hands to tell the materials where to go. It allows the emotional!spiritual channels to open up. This does not happen because we think about, explain it, or conceptualize it. It occurs because we put our hands in it and that act takes us somewhere else.60

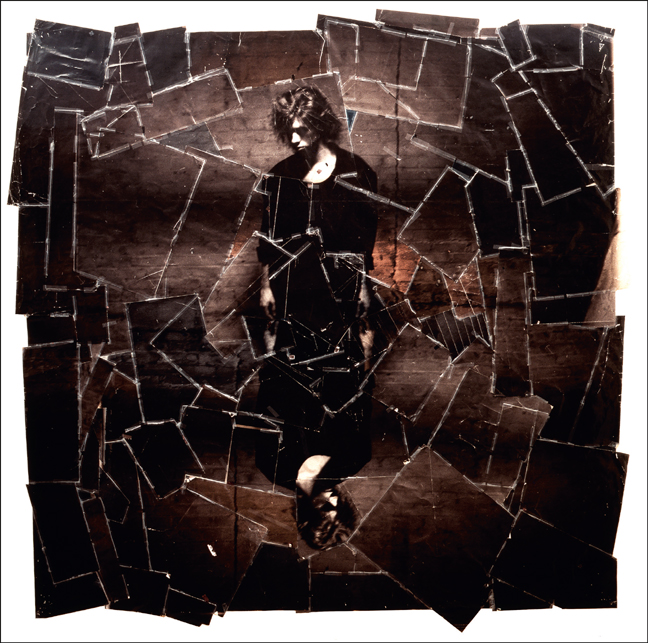

Doug Starn and Mike Starn (b. 1961), the Starn Twins, have cultivated ideas of replication and the possibility of identical doubles. Often consciously basing their work on historical paintings, the Starns were first noticed in the 1987 Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial, a notable exhibition of contemporary art, for their brusqueness of surface and inconsistencies of scale and space created by splattering chemicals, tearing prints, and putting pictures together with transparent tape. A pseudo-antique patina of cracked emulsions, creases, and torn edges gives their images a sense of time and decay, making their often familiar content seem like a retelling of Western history. Their hand-based studio method, embracing the fluidity of time, is not so much a postmodern deconstruction as it is a romantic reconstruction, recalling the building of Western civilization. The borrowing of figures and compositional schema from past artistic movements places them in these earlier traditions while hinting at how the past can easily invade the present. Their complex sculptural approach, relying on forging connections among glass, Plexiglas, wood, silicone, and pipe-clamps, yields seductive, fetishistic objects that mock the efforts of collectors and curators to preserve original works. The Starns, rather than neutralizing the physical carrier of the photographic message, make the carrier as aesthetically consequential as the image.

© DOUG and MIKE STARN. Double Stark Portrait in Swirl, 1 985–86. 99 × 99 inches. Toned gelatin silver print and tape.

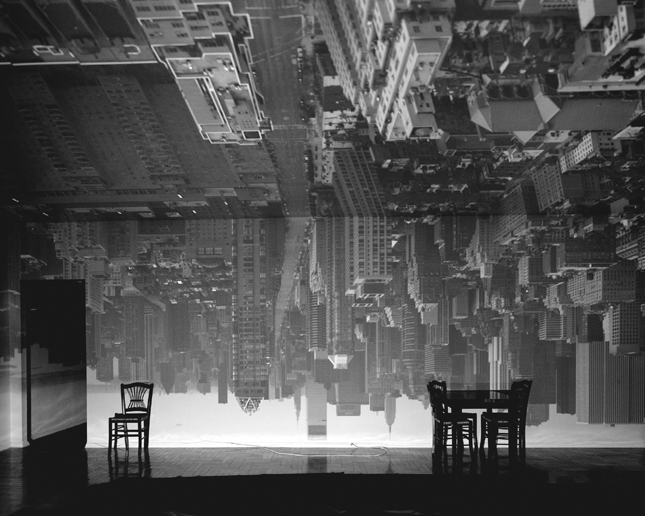

© ABELARDO MORELL. Camera Obscura Image of Manhattan View Looking South in Large Room, 1996. 20 × 24 inches. Gelatin silver print.

COURTESY Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.

Against the widening backdrop of digital technology artists like Adam Fuss (b. 1961) and Abelardo Morell (b. 1948) alter conventional photographic notions of time and space by returning to the most direct and fundamental principles of photography. Fuss dispenses with the camera to produce large color photograms that remove the mechanical obstacles between himself and his subjects. Referencing one of his photograms that incorporates egg yolk, Fuss states:

I like the idea of things being as they are. A photogram can he two things at the same time. It’s light passing through the egg yolk; the fact that it looks like the sun is wonderful, but it is an egg yolk. It’s the perfect metaphor.61

Morell was a street photographer who now converts rooms into a pinhole camera obscura. He then operates a view camera inside the camera obscura to make extended (eight hours and longer) exposures that record the composite image produced by the pinhole projection of what is outside the space upon whatever is inside the room itself. This dualistic engagement transforms the subjects into alternative, upside-down visions of themselves.

© CHRIS MCCAW. Sunburn GSP #676 [Son Francisco Bay), 2013. 8 × 10 inches.

Gelatin silver paper negative.

In the making of his unique gelatin silver paper negatives, McCaw exclaims: “Once you start a fire in your camera it is a game changer. You see smoke and it smells like roasted marshmallows. None of the shutters work on any of my lenses. They have been cooked! It is so basic. It’s just glass and a lens cap.”62

COURTESY of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

For his Sunburn work, Chris McCaw (b. 1971) builds his own cameras and places expired gelatin silver paper into the camera’s film holders. Then he makes extended exposures ranging from several hours up to a 20-hour duration that essentially cooks his camera and materials. The subject of McCaw’s extensions of time, featuring the horizons of primordial landscapes and seascapes, is the sun’s trajectory as it literally burns its path across the paper’s surface. Often, the energy from the sun sears directly through the photographic paper while solarizing the resulting image—converting it from a negative to a positive. The solarization process that produces this tonal reversal is the result of massive overexposure, and it can produce iridescent purple tones that McCaw enhances with selenium toning.

McCaw’s recording of our sun’s path turns what would conventionally be considered an aesthetic and technical failure into something of wonderment, by giving representation to a familiar yet intangible phenomenon—our earth’s orbit around the sun—in a forthright manner. These gestural and visceral images, rendered by fire and smoke, convey the friction between creation and destruction. There is a cosmic sense of substantialness in McCaw’s pictures. His stunning prints possess a deep and fragile elemental connection to the earth, for they arise as three-dimensional, alchemical transformations of the landscape that bear slight resemblance to a straight photograph. The paper negatives record a spatial distillation of nature that blends movement, space, and time to materially challenge the longstanding pictorial formulas of flatness and stationary time, thereby demonstrating the incredible flexibility of chemical photography.

NOTES

1See Omar Kholeif, ed., Moving Image: Documents of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2015).

2Editioning is the process of making a limited number of prints in order to make each print more profitable. Each print is signed and numbered, such as 07/25, to indicate its unique number within the size of the edition.

3See the 2015 exhibition The Immovable Camera: Copy Art in the Bay Area 1980—1984 at www.lightresearch.net. It was first shown at the Tower Fine Arts Gallery on the campus of the College at Brockport, State University of New York, October 27–December 11, 2015.