5

Chinese Cross-Border M&A into Industrialized Countries

The case of Chinese acquisitions in Germany

Introduction

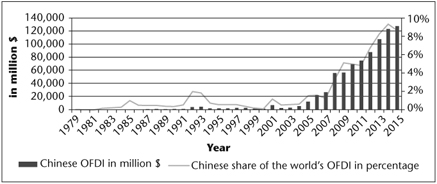

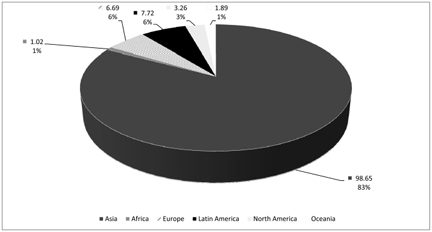

Chinese enterprises had established more than 25,400 entities in 184 foreign countries by the end of 2013 (Ministry of Commerce, 2014). In terms of outward foreign direct investment (OFDI), China ranks third worldwide, contributing a share of 8.6 per cent to worldwide OFDI, which highlights its growing importance as a foreign investor (UNCTAD, 2015). While the main target of Chinese OFDI is still South and East Asia (Ministry of Commerce, 2010; Morck et al., 2008), OFDI into industrialized countries is rapidly increasing. Cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As) accounted for 63.9 per cent of the total Chinese OFDI in 2013 (Ministry of Commerce, 2014), and are the most common ways of Chinese OFDI entering industrialized countries. As Chinese OFDI is increasingly motivated by the procurement of intangible assets, M&As are a rapid and highly efficient route to increase knowledge and technology and to gain reputation through the acquisition of well-reputed brands.

Figure 5.2 Destinations of Chinese OFDI in 2014 (in billion US$)

Source: 2015 China Statistical Yearbook

In the last decade, China’s cross-border M&A transactions have mainly targeted Europe and North America due to its growing interest in strategic assets, including intangible assets, such as the acquisition of advanced technology in high-end manufacturing and brands, marketing, R&D knowledge, and advanced managerial strategies (e.g. Boateng et al., 2008; Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Cui and Jiang, 2010; Luo and Tung, 2007; Luo et al., 2010; Morck et al., 2008). By addressing the shortage in the aforementioned areas, China is trying to overcome the problem of being an international latecomer (Boateng et al., 2008; Child and Rodrigues, 2005). By increasing strategic assets through acquisition, China is now in a position to increase its international reputation and prestige (Deng, 2009), as well as firm-specific intangible assets, such as superior resources and skills that are not available at home (UNCTAD, 2006).

Although opportunities for China’s internationalization have increased recently, partly due to the global financial crisis, challenges abroad raised by host country governments (e.g. CSR, transparency, environment protection) are mounting (Ministry of Commerce, 2013; Sauvant, 2013). These new challenges are in addition to existing challenges of liability of foreignness, cultural integration, acquisition of knowledge and integration to improve post-M&A innovative performance (Deng, 2009). Furthermore, China still suffers from a shortage of internationally experienced managers to run foreign companies. Time will tell whether the post-acquisition process, and the aforementioned challenges, can be handled successfully.

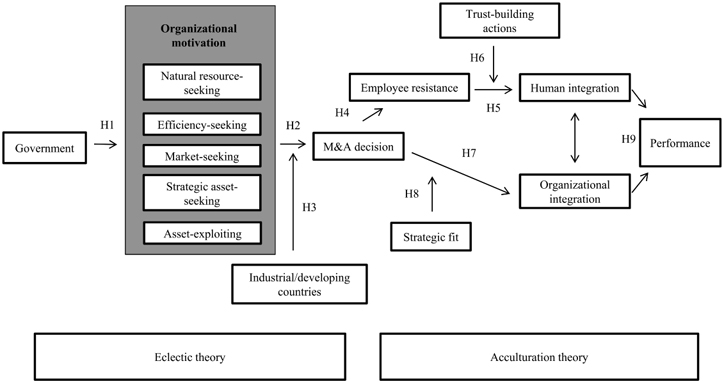

Despite the increasing importance of Chinese M&A (Cui and Jiang, 2010; Hong and Sun, 2006), little research exists on the outward M&A of Chinese and other emerging market multinational enterprises (EM MNEs). The small amount of research that exists has usually merely touched upon either some aspects of the pre-M&A phase or the post-M&A phase. This nascent body of research suggests that the M&A motivations and implementation of EM MNEs differ from that of MNEs from industrialized economies. Thus, more research is clearly needed. To fill this void, the purpose of this chapter is to increase our understanding of the cross-border M&As of Chinese MNEs into industrialized countries. Responding to the call for an understanding of the whole process of M&As (Gomes et al., 2013) we investigate both the pre-M&A and post-M&A integration phases. We integrate M&A, FDI and China-specific literature to develop a conceptual model of Chinese outward M&As. In addition, we use the Sany-Putzmeister acquisition, one of the most well-known Chinese M&A acquisitions in Germany, as a case to illustrate our model. To gain further insight, we use the LexisNexis database for a press and media analysis. Altogether, we analysed forty-five articles that were published in 2012 and 2013 – up to two years after the acquisition was announced.

Our contributions are threefold. First, we build on and extend established M&A models (Birkinshaw et al., 2000, Larsson and Finkelstein, 1999; Nahavandi and Malekzadeh, 1988) by integrating and linking them to crucial factors of the pre- M&A stage, as a holistic M&A process is a complex and understudied phenomenon (Gomes et al., 2013). As for the pre-M&A stage, we focus on the motivations for internationalization, because motivations largely vary between EM MNEs and MNEs from industrialized countries and have a profound impact on the post-M&A integration phase. Second, we extend eclectic theory to the context of Chinese MNEs by adding context specific variables such as government influence and explore them in the context of EM MNEs’ M&As targeting industrialized economies. Third, we develop our model by combining the strategic management and organizational behaviour streams of research in an M&A context with the existing FDI literature, with a focus on highlighting the success factors of Chinese cross-border M&As, deriving important practical and theoretical recommendations.

The remainder of this chapter is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of the development of Chinese OFDI, M&As and the Putzmeister case, providing the grounding for our conceptual model. Second, we discuss patterns of the pre-merger decision and motivations by drawing on eclectic theory, and then the post-merger process by drawing on acculturation theory. Based on these theories and China-specific evidence, we develop a number of propositions. Finally, we conclude by discussing the findings and suggest implications for Chinese and other EM MNEs.

The development of Chinese outward foreign direct investment and M&As

OFDI is no longer a one-way street from industrialized to developing countries (Klossek et al., 2012). Chinese OFDI started after the launch of the opening policy initiated by the Chinese government in 1978, a number of years before the well-known cases of Lenovo’s acquisition of the IBM computer business and follow-up acquisitions by, for example, Haier, TCL and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) (Morck et al., 2008).

Chinese OFDI was reinvigorated in 1999 when the Chinese government initiated the going-out strategy as part of the 10th Five-Year Plan (2001–2005), which facilitated OFDI (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Luo et al., 2010). This strategy promoted the overseas investment of Chinese enterprises in those regions and industries that were classified as strategically important.

Although direct political guidance by the Chinese government plays a minor role in corporate investment decisions, the government does have a guiding influence and is responsible for the approval of internationalization decisions. It is currently trying to simplify the approval process for OFDI (Li, 2014), as well as incentivizing the internationalization and growth of promising – mostly state-owned – enterprises, for example by offering low-interest loans and tax deductions or even allocating banks to the respective companies (Buckley et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2010; Zhang and Daly, 2011). In 2003, privately owned enterprises, such as Lenovo, Huawei and Haier, were granted permission to apply for overseas investments (Buckley et al., 2008), a privilege that was previously granted only to Chinese SOEs (Morck et al., 2008). The current trend shows that mainly Chinese non-SOEs or enterprises with limited bureaucratic interference are those that are internationalizing (Child, 2011; Child and Rodrigues, 2005).

The going-out strategy is consistent with China’s need to spend its foreign currency reserves, caused by a consistent trade surplus and a large savings–investment gap (Chen and Young, 2010; Hong and Sun, 2006). According to UNCTAD (2016), the annual investment flows from China have increased significantly since the launch of the strategy (also see Figure 5.1). The 12th Five-Year Plan (2011–2015) aimed to accelerate the going-out strategy, with plans to improve the legal environment, management learning and innovation in the M&A context. The further development of the OFDI curve and the associated political regulations which predominantly shaped it in the past are summarized in more detail in Buckley et al. (2007), Luo et al. (2010) and Zhang and Daly (2011). In more recent years, the financial crisis, by damaging the world’s economies, has put less affected Chinese companies in a position to acquire ailing Western businesses (Chen and Young, 2010; Deng, 2009).

Chinese foreign acquisitions show several distinctive features: first, a tenfold increase in volume between 2005 and 2012 (UNCTAD, 2013); second, acquiring companies are mainly large Chinese enterprises with international experience; third, target firms are located mainly in industrialized countries and face strategic and/or financial difficulties, and are generally concentrated in the ‘seven strategic pillar’ industries (resource, energy, telecommunications, electronics, machinery, home appliances and automobiles), as communicated in the Five-Year Plans (Rui and Yip, 2008). China’s motivation for these acquisitions is its desire to address its competitive disadvantage and to ‘catch up’ with industrialized countries (Boateng et al., 2008; Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Luo and Tung, 2007; Luo et al., 2010; Rui and Yip, 2008), and also to counter-attack the presence of large foreign MNEs in the Chinese market, bypass stringent trade barriers, alleviate domestic institutional constraints, secure preferential treatment offered by home governments, and exploit their advantage in other developing markets (Luo and Tung, 2007).

Chinese investments in Germany tripled between 2005 and 2010, offering a bright outlook for the next decade, rising from almost zero at the beginning of the 1990s and reaching a volume of US$1.43 billion by 2014 (OECD, 2014). Prime targets of Chinese M&A investment are German small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), because they possess the desired intangible skills and can be acquired easily due to the fact that 37 per cent of German family-owned SMEs face serious problems in appointing successors (DIHK, 2011). One major case that possesses such characteristics is that of Putzmeister. Facing financial difficulties and failing to identify a successor, Putzmeister’s owner and founder Karl Schlecht announced in January 2012 that he had decided to sell the company to the Sany Heavy Industry Group, a Chinese competitor (see Table 5.1). This transaction caused a sensation in the German media, as it was the first time a German global market leader had been acquired by a Chinese company. Some of the public outcry following the announcement of the deal was characterized by prejudice; other criticisms focused on the potential collapse of ‘Germany’s economic backbone’, the German ‘Mittelstand’ (SMEs).

Table 5.1 Comparison of the Sany Heavy Industry Group and Putzmeister in 2011

| Sany Heavy Industry Co., Ltd. | Putzmeister GmbH | |

|

| ||

| Founded | 1989 | 1958 |

| Products | Heavy machinery (e.g. excavators, cranes) for construction industry | Concrete pumps and related modules |

| Origin | Changsha, Hunan Province | Aichtal, Baden-Württemberg County |

| Ownership | Privately owned (LIANG Wengen) | Family owned (Karl Schlecht) |

| Employees | Approx. 50,000 | Approx. 3,000 |

| Sales | e9.5 billion | e0.6 billion |

| Vision | ‘Quality changes the world’ | ‘Be happy while serving, improving and creating values’ |

Source: Homepage of Putzmeister GmbH and Sany Heavy Industry Co., Ltd.

Without first informing employees, who heard the news from the media, Schlecht sold his company to its largest Chinese rival. This surprising announcement triggered a wave of uncertainty and anxiety, fuelled partly by prejudice, leading to demonstrations encouraged by the works council. Hence, the preconditions for the integration of Putzmeister into the Sany Heavy Industry Group were rather poor. One factor that made the transaction necessary was the fact that the German firm’s sales had decreased by 63 per cent during the global economic crisis. As Putzmeister’s CFO stated, the firm now needed a ‘strategic partner’, especially as a large portion of worldwide growth in the construction industry was generated within China, and Putzmeister had an inadequate presence there. In an interview, Schlecht explained the strategic necessity of his sale of Putzmeister. He claimed that the firm was not sufficiently diverse to compete over the long term and asserted that the main reason for this was its business model’s sensitivity to the overall economic performance of the cyclical industry in which it competed.

Theory and proposition development

The purpose of this chapter is to develop a model for the whole process of M&A for the case of Chinese M&As in industrialized countries (see Figure 5.3). To do so, we combine relevant theories from the pre- and post-merger phases. We explain the underlying theories, constructs and relationships in more detail in the following subsections.

Pre- and post-M&A based on eclectic and acculturation theories

The eclectic theory of direct investment provides a comprehensive theoretical explanation and framework of why firms engage in OFDI, including cross-border M&A (Dunning, 1977). According to the logic of the framework, firms go abroad if they meet three conditions. First, they need to have an ownership advantage – that is, tangible or intangible assets (e.g. advanced technology, exclusive access to inputs or a high capacity for innovation) that provide them with advantages over firms in a foreign market. Second, when exploiting ownership advantages, this must involve less transaction costs in order to internalize this advantage within the organization, rather than selling the ownership advantage to other firms. Third, decision-makers need to ask themselves whether their firm can exploit certain locational advantages in the respective host country, such as network linkages (Chen and Chen, 1998, 2004; Child and Rodrigues, 2005), favourable legislation, low input prices or an efficient infrastructure.

However, the eclectic theory, by providing an economic rather than a political or social view of the internationalization process (Child and Rodrigues, 2005), cannot fully explain the Chinese OFDI paradigm as it overlooks the role of government, which is a dominant actor in the M&A process of EM MNEs, as well as the motivations regarding internationalization decisions, which are different from what we know of the Western context. Therefore, researchers have already pointed out the need for an extended framework of internationalization theories, regarding internationalization solely as the logical consequence of a competitive advantage over firms in another market, to meet the distinctive features of developing country multinationals (Athreye and Kapur, 2009; Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Fortanier and Tulder, 2009; Kumar, 2009; Narula, 2012; Zhang and Daly, 2011). Government influence or entrepreneurial choice of internationalization or a co-evolution of the two, which would foster exchange and development of the usual path dependency (Rodrigues and Child, 2003) proposed in the eclectic theory, are regarded as distinctive features. EM MNEs can be especially motivated to use international expansion as a springboard to tackle ownership disadvantage. This view is consistent

Figure 5.3 Model

with the existing literature, distinguishing between an asset-seeking and an asset-exploiting perspective of internationalization (Makino et al., 2002). Regarding the Chinese context, OFDI, mostly in the form of M&A, is both asset-exploiting and augmenting (Chen and Young, 2010; Cui and Jiang, 2010; Dunning, 2006; Luo and Tung, 2007; Yiu et al., 2007) – for example, Lenovo’s acquisition of IBM – providing a platform for market entrance as well as the acquisition of technological knowledge. Dunning himself acknowledged this weakness, stating that there are ‘two groups of reasons why any firm would engage in OFDI: the first is to exploit existing assets or competitive capabilities, and the second is to augment them’ (Dunning and Lundan, 2008: 187).

A major challenge for cross-border M&A is the potential clash of cultures (e.g. Brannen and Peterson, 2009; Froese et al., 2008) during the post-acquisition phase. Although diverse terminology exists for the various acculturation phases (e.g. Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991), we follow Berry (1980) and Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1988), who categorize the cultural change process following M&A into four different types: integration; assimilation; separation; and deculturation. Integration refers to a process whereby the acquiring company intends to maintain some of the characteristics of the target company, while implementing some of its own elements. Assimilation refers to a process where the acquiring firm imposes all or most of its practices on the target firm. Separation implies that the target company remains almost untouched. In deculturation, a completely new culture, different from those of the acquiring and target companies, is created. Chinese MNEs in industrialized countries tend to follow the separation and integration approaches. Acquired companies, such as Putzmeister, remain almost unchanged, and are therefore characterized by a ‘light-touch integration’ (Liu and Woywode, 2013). This integration form resembles a combination of the separation and integration approaches.

Pre-merger phase

According to Gomes et al. (2013), the main success factors in the pre-merger stage are: choice and evaluation of the strategic partner, pay the right price, size mismatches and organization, overall strategy and accumulated experience on M&A, courtship, communication before the merger, and future compensation policy. However, prior research draws on M&As from industrialized countries in the Western Hemisphere. Therefore, we intend to highlight success factors of pre- and post-M&A stages of EM MNEs in the following paragraphs.

Government and OFDI

In China, investments abroad, including cross-border M&As, are still heavily sponsored, supported and controlled by governmental institutions (Wang et al., 2012a, 2012b; Zhang et al., 2011), the most influential of which are the State Council, Ministry of Commerce (MOC), People’s Bank of China, State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), and State Development and Reform Commission (Luo et al., 2010). However, the influence of government involvement is largely dependent on the level of government affiliation and the degree of state ownership (Wang et al., 2012b). The high involvement of governmental institutions sometimes makes it necessary to align the OFDI strategy with the strategy of the respective company. However, this alignment is impeding entrepreneurial innovation, development and freedom (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Cui and Jiang, 2010; Deng, 2009). Due to the sometimes differing political motivations behind internationalization (Chen and Young, 2010; Luo and Tung, 2007), principal–principal governance conflicts can arise between the major shareholders, mostly consisting of Chinese governmental institutions (Morck et al., 2008), and other (non-governmental) minor shareholders. Given this backdrop, one of the emerging questions is whether the motivation behind internationalization is institutionally embedded or independently (entrepreneurially) driven (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Rui and Yip, 2008).

In the case of Chinese cross-border M&As, all the internationalization drivers present in the organization are strongly influenced by the government. Among the Chinese companies benefiting from governmental support, there are several firms that are now able to compete internationally (Deng, 2009), as indicated by the number of Chinese companies that were present in the Fortune Global 500 list in 2013 (CNN Money, 2013). Chinese companies which are successful in the domestic market are increasingly willing to establish themselves as global players, venturing abroad mostly through the means of cross-border M&A (Deng, 2009; Luo and Tung, 2007).

The original OLI framework does not account for government influence, which is a crucial factor, especially for EM MNEs (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Dunning and Narula, 1996) that are highly dependent on support from the government to account for lacking competitiveness. Even in the case of the privately owned Sany Heavy Industry Group, bonds and close contacts with the Communist Party are favourable and contribute positively to the corporate strategy (CNN, 2011). Additionally, mechanical engineering is one of the encouraged sectors, enjoying ‘preferential policy and government support associated with funding, tax collection, foreign exchange, customs, streamlined approval process and others’ (Wang et al., 2012a: 431), thereby creating synergy effects between government policy and firm strategy. As the impact of government affiliation is indirect through networks, even private firms’ decisions to internationalize might be driven, at least to some degree, by the government (Wang et al., 2012b), which can have an influence on location, type and level of OFDI. As the government is able to influence the ability and willingness of EM MNEs to internationalize, its field of influence concerns, for example, strategic objectives and decisions, availability and costs of various resources, usage of these resources, capabilities, provision of valuable knowledge, information and intermediary services, as well as transaction costs associated with the cross- border expansion of the firm (Wang et al., 2012b). In addition to the degree of involvement, motivations to support the institutionalization of specific firms can vary in terms of government level (e.g. state or provincial level versus city or county level) (Wang et al., 2012b).

The motivations for cross-border M&As

The eclectic theory literature suggests four possible motivations for OFDI (Dunning, 1977, 1993). First, OFDI can be driven by natural resource-seeking motivations. For example, such motivations can be observed in the various cases of Chinese firms in African countries (Dupasquier and Osakwe, 2006). Second, efficiency- seeking motivations are related to a firm’s search for competitiveness. Efficiency can be enhanced by exploiting country-specific advantages, such as low labour costs, which is a less relevant factor for Asian companies moving to industrialized countries (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Zhang, 2003). Third, a firm’s internationalization can be driven by market-seeking motivations. Certain markets might be attractive because of their size, growth, per capita income or certain aspects of consumer behaviour. Sometimes there is also an interplay of home country market imperfections, institutional constraints (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Deng, 2009; Zhang and Daly, 2011), domestic market competition (Chen and Young, 2010) and host country market advantages. Finally, a driver for OFDI can be the search for strategic assets. These can be assets that empower a company’s strategy and provide advantages in the long term, and are acquired to enhance the firm’s portfolio and ease the imbalance caused, for example, by superior technology available in firms in industrialized markets. In sum, as Wang et al. (2012b) argue, government involvement influences the level of overseas investment, its location (industrialized or developing countries) and its form (various asset-seeking or -exploiting motivations).

In the case of the Sany Heavy Industry Group’s acquisition of Putzmeister, the most prevalent motivation was strategic asset-seeking – the pursuit of Putzmeister’s concrete pump technology (a technology against which Sany had tried – and failed – to compete for almost twenty years). Furthermore, market-seeking motivations played a role because Putzmeister’s brand name facilitated access to other relevant markets, providing further evidence for the theoretical reasoning by Makino et al. (2002) and Yiu et al. (2007) that strategic asset-seeking and market-seeking motivations play significant roles in investments in industrialized countries. Additionally, most companies from developing countries have no experience in operations in the international business context. Therefore, they rely heavily on the comparably highly skilled staff of the potential target firm.

For a correct understanding of the model, it should be added that OFDI is driven in practice by a number of these factors, not by a single one. The four motivations mentioned by Dunning (1993) include only situations in which a firm seeks certain assets in a foreign market. However, as conventional international business theory suggests, there are also situations in which a firm already has an advantage and internationalizes its activities in order to exploit these firm-specific ownership advantages in new settings (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Guillén and García-Canal, 2009; Yiu et al., 2007). Asset-exploiting motivations mainly play a role when internationalizing into developing countries, although some EM MNEs have succeeded in exploiting their assets in industrialized countries (Luo and Tung, 2007).

Country context

The strategic motivations explained above vary depending on the economic development level of the target countries. Asset-exploiting motivations are drivers of internationalization decisions in other developing countries, located for instance in Southeast Asia or Africa, particularly those that are less developed than China and have lower labour costs, which have become comparably higher in China. In regards to asset-seeking motivations, industrialized countries offer more opportunities to increase their assets, not only in regard to natural resources or market access, but nowadays more in the context of strategic assets, such as brand reputation, higher management skills and innovative and high-quality technologies. Chinese and other EM MNEs are still lacking these assets and need to absorb them in order to become global players. Therefore, the motivations differ depending on the target country.

The Sany Heavy Industry Group was already well established in the domestic market; however, it was eager to develop its competitive advantage in order to do business abroad. Therefore, Sany aimed to invest in industrialized countries, such as Germany, that were able to offer it the vital strategic assets (e.g. superior technology and brand reputation) it needed. Thus, Sany acquired Putzmeister.

Privately owned EM MNEs tend to invest into industrialized countries, and are often driven by their own limited legitimacy (e.g. lack of relationships to government officials) and their experience of discriminatory policies in their domestic market (Wang et al., 2012b). Enhancing competitiveness and capabilities in industrialized markets is a common driver of companies affiliated with high levels of government that are eager to generate innovativeness and address competitive disadvantages, for example through the acquisition of foreign technology (Cui and Jiang, 2012; Wang et al., 2012b).

Proposition 3: The economic level of the target country moderates the motivations of Chinese cross-border M&As, insofar as asset-exploiting motivations lead to investment in developing countries, whereas asset-seeking motivations lead to investment in industrialized countries.

Post-merger phase

The post-merger integration phase is essential for the success of an M&A. However, the post-merger integration is challenging due to cultural and institutional differences and the resistance of various stakeholders, for example government institutions and employees in the target country (Björkman et al., 2007; Datta, 1991; Froese et al., 2008; Stahl and Voigt, 2008). Substantial research has examined the antecedents and mechanisms of M&A success (e.g. Almor et al., 2009; Dauber, 2012; Weber and Tarba, 2011; Weber et al., 2009, 2011). However, little research has investigated the post-merger phase of acquiring Chinese and EM MNEs, not to mention the link between pre-M&A motivations and post-outcomes. In the following subsections, we develop several propositions concerning the underlying mechanisms and moderating factors leading to successful organizational and human integration and, ultimately, M&A success.

Cross-border M&A and employee resistance

Organizational change typically follows M&A deals which can have negative consequences for the employees of the acquired firm (e.g. layoffs, relocation, career disruption) and cause negative reactions among this cohort, such as uncertainty, anxiety, distrust, tension and even hostility (Larsson and Finkelstein, 1999). Hence, when uncertainty about the individual employee’s future (e.g. rumours about layoffs) is paired with prejudiced-induced uncertainty about the nature and characteristics of the acquiring firm, employee resistance is likely to be high (Morck et al., 2008).

Further, when the two cultures collide, negative behavioural patterns influencing firm performance, such as lower productivity, absenteeism, lower job satisfaction and commitment, may arise (Froese and Goeritz, 2007; Jöns et al., 2007). In the case of Sany and Putzmeister, these psychological and behavioural patterns, known as ‘merger syndrome’, occurred immediately after the announcement of the acquisition. Sometimes individual articles can display both negative and positive attitudes to foreign acquisition. For instance, a piece in the German newspaper TAZ had the rather pejorative headline ‘When communists go shopping’ but then went on to say: ‘We prefer the Chinese because they have a long-term strategy, whereas Anglo-Saxon private equity firms are all about a quick turnaround’ (Von Leesen, 2012). Political manoeuvring or demonstrations, as in the Putzmeister case, can exacerbate negative feelings, such as hostility, towards the acquiring firm (Seo and Hill, 2005) and also harm production because of employees’ absence from work. Although Sany faced some trouble during the initiation phase, researchers have observed that, in general, acquisitions by privately owned firms are less troublesome than those by SOEs, which often invest in utilities and infrastructure industries (Zhang et al., 2011).

Prejudice towards acquiring companies, based on a lack of knowledge about foreign cultures, can increase the level of anxiety, potentially endangering the acquisition of the desired assets (Child and Rodrigues, 2005). The psychic distance between the Chinese company and the German context further increases the liability of foreignness and results in a strategic disadvantage for MNCs operating abroad (Child et al., 2002; Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Zaheer, 1995). Sarala (2010) showed that cultural differences increase post-acquisition conflict, whereas partner attractiveness reduces post-acquisition conflict. According to acculturation theory, this psychological acculturation phenomenon leads to a shift in the behaviour of the individual after undergoing the processes of culture shedding, culture learning and culture conflict (Berry, 1997). The first two stages imply a degree of ‘unlearning’ of one’s own cultural aspects, and simultaneous ‘replacement by behaviours that allow the individual a better fit with the society of settlement’ (Berry, 1997: 18). In our case, the employees needed to adjust to the new environment of the M&A, which would likely result in initial employee resistance.

Employee resistance and human integration

Human integration, a crucial part of the integration process, is defined as ‘the creation of positive attitudes towards the integration among employees on both sides’ (Birkinshaw et al., 2000: 400). Employee resistance, often caused by cultural differences between the two companies involved, is an influential factor that is especially important in the M&A context, which challenges human resource management during the integration phase of the merger. Drawing on evidence from research on foreign subsidiaries, localization is beneficial for organizational commitment among host country nationals (Hitotsuyanagi-Hansel et al., 2016), which further suggests that consideration of the host country employees is vital. These findings can also be transferred and applied to the M&A context, with its diverse cultures. However, research has also shown that national cultural differences are not as problematic as is often assumed, and, in addition to organizational differences, may even be positively associated with knowledge transfer (Vaara et al., 2012). Additionally, the limited operational integration of Putzmeister might have helped to reduce the likelihood of post-acquisition cultural problems. As Shenkar (2001: 527–528) mentioned: ‘how different one culture is from another has little meaning until those cultures are brought into contact with one another’.

According to acculturation theory, human integration can be accomplished only if the groups involved are free to choose whether to adopt the integration mode. However, in our M&A context, employee resistance impedes mutual accommodation and acceptance by both groups (Berry, 1997). As the management is a crucial player with respect to employees’ reactions towards the M&A (Hildisch et al., 2015), it has the potential to foster positive adaptation to the new cultural context between the employees (Berry, 1997). The ‘light-touch integration’ approach of the Chinese acquirer was meant to overcome the pre-merger conflicts and acculturative stress by keeping the operations of the two companies separate.

Trust-building actions

By ‘trust-building actions’, we mean actions undertaken by both sides, including trust and respectful communication, involvement in the organizational structure, as well as measures to reduce cultural distance, which will be explained in more detail below.

In addition to the findings of the Putzmeister case, prior studies found that trust-building actions can be a success factor for the integration of an acquired firm (Björkman et al., 2007). Communication is a crucial factor to develop trust among employees during the integration (DiFonzo and Bordia, 1998), which subsequently avoids negative outcomes for the organization (Bordia et al., 2004). Stress and resistance can be reduced through culturally active communication, participation and commitment (Froese and Goeritz, 2007). All of these efforts help to build trust among the employees of target companies.

Therefore, after the rough start and soon after the protests, the Sany Heavy Industry Group launched a number of trust-building actions. It communicated that no one would be laid off. Moreover, Wengen Liang, the founder and chairman of the Sany Heavy Industry Group, expressed his admiration and respect for the entrepreneurial achievements of Putzmeister whenever the opportunity arose. For example, when he met Schlecht for the first time, Liang said: ‘You are my teacher’ (Fischer, 2012; Klawitter and Wagner, 2012). Further signs of mutual trust can be found on both sides. For instance, Liang declined to conduct a due-diligence audit, which is usually a prerequisite in an acquisition of this size. This decision strongly impressed Putzmeister’s top management and employees. Furthermore, Schlecht was invited to become a ‘superior consultant’ for the Sany Heavy Industry Group. (He accepted the offer but refused to be paid.) Additionally, Schlecht publicly highlighted his respect for the Chinese and for Sany’s corporate culture. He emphasized the congruence between the values of his firm and the values that Sany defined in its corporate statements. Additionally, he praised China’s Confucian heritage, which he said was apparent in the natural and courteous way in which Sany wanted to learn from Putzmeister. Even on lower hierarchical levels, the relationship between the two firms was respectful and trustful. Another sign of trust was the appointment of Putzmeister’s CEO to Sany’s board, which made him the only German on a Chinese board of directors at that time (Hirn, 2013).

Due to employee resistance, the willingness to adopt the acquirer’s culture and practices was low, whereas the will to preserve one’s own culture was high, leading to the separation mode of acculturation. However, changes in the acculturation mode constitute the dynamic nature of the M&A integration process, and make a continuous adjustment important (Nahavandi and Malekzadeh, 1988). Notably, intercultural training and Chinese language courses were immediately offered to the employees in order to decrease the perceived cultural distance to the unknown Chinese company.

M&A decision and organizational integration

Acquiring companies can pursue different levels of integration, usually simplified as a high versus low level of integration (Haspeslagh and Jemison, 1991). The organizational integration adopted by the Chinese MNEs is mostly characterized by a ‘light-touch integration’ (Liu and Woywode, 2013), which does not involve too many changes and comprises a loose integration, giving Putzmeister greater autonomy. This autonomy is reflected by the physical absence of Sany Heavy Industry Group managers at Putzmeister’s headquarters (Hirn, 2013), as well as an absence of intercompany exchange among production workers or mid-level management. In daily business, the changes for Putzmeister’s employees were marginal. However, Putzmeister recruits German engineers for Sany. Also, Sany sends delegations to Germany on a regular basis and tries to learn from Putzmeister. Many of the German manufacturer’s processes have been adopted in China (Klooß, 2013). Consequently, the Chinese CEO made the following statement: ‘It feels like they bought us and not the other way around’ (Simon, 2012). Additionally, the two organizations agreed on a separation of markets: while the Sany Heavy Industry Group concentrates on the Chinese market, Putzmeister covers the rest of the world. Thus, there is less potential for conflict, and competences and areas of activity are clear. The businesses are kept autonomous and independent, and little cultural or behavioural assimilation takes place.

According to acculturation theory, a fit between culture and strategy is of the utmost importance in order to achieve organizational effectiveness. Furthermore, factors determining the course of acculturation are the choice of degree of relatedness (diversification strategy) and perception of the attractiveness of the acquirer (Appelbaum et al., 2000; Nahavandi and Malekzadeh, 1988). In the case of Putzmeister, the two companies involved are related in their business. However, against the usual assumption of acculturation theory regarding the relatedness of business, there has been no desire to intervene in daily business operations, and the acquirer has not imposed its culture on the acquired company (Nahavandi and Malekzadeh, 1988), as already discussed in the previous proposition.

Due to the initial protests and prejudices against Sany, which were shared by most of the employees of the acquired firm, the perceived attractiveness of Sany, the acquirer, was low, whereas the wish of employees to preserve their own (German) culture was high, suggesting a separation of businesses. We assume that the strategic fit in this case is limited to financial issues on the side of Putzmeister and to technological and symbolic images on the side of Sany. To accomplish these benefits, only limited organizational change is needed.

Strategic fit

According to Schlecht’s analysis, the alternative to the corporate sale would have been bankruptcy. Thus, the strategic fit from Putzmeister’s perspective applies not only to its employees, who, in the long-term perspective, gained job security, but also to the owner, who reached his personal altruistic goals. Putzmeister retained its financial strength after undergoing a restructuring process following the economic and financial crisis. The Sany Heavy Industry Group not only covered all existing debts immediately, but also gave Putzmeister funds for further acquisitions and thereby fostered investment and growth. As a strategy expert stated in the press, ‘the two companies are a good match, and if the managers can get along we could see the first Chinese–German success story’ (Simon, 2012).

For the Sany Heavy Industry Group, an important benefit of the acquisition was the access to Putzmeister’s technology, in particular the construction plans of the concrete pumps, which provided it with a competitive advantage. Additionally, the central location in Germany and the possibility to use Putzmeister’s sales and service infrastructure facilitated access to the entire European market for Sany. In turn, Sany now sells Putzmeister’s concrete pumps in China as a ‘premium product’. Furthermore, the Chinese firm was able to gain a lot of public attention, which led to greater prominence and a higher reputation in Europe.

Moreover, synergies were expected, and joint research and development activities were planned. According to Putzmeister’s CEO, product quality between China and Germany would have to be adjusted to accomplish equal standards. The Sany Heavy Industry Group is now considering to serve as a component supplier (e.g. hydraulic cylinders) for Putzmeister’s concrete pumps (Klooß, 2013), which fosters a vertical integration of its supply chain and might generate cost advantages. Taken together, a strategic fit on both sides is crucial for the success of M&As.

Proposition 8: Strategic fit between the acquiring and the acquired company moderates the relationship between the M&A decision and organizational integration insofar as higher strategic fit leads to greater organizational integration.

Human and organizational integration and performance

To achieve a successful acquisition, organizational and human integration should both be of a high level. The future success of the Putzmeister acquisition is a matter of mutual development of both human and organizational integration. However, as the integration strategy is an ongoing process, this phase may last up to seven years (Birkinshaw et al., 2000). In general, human integration has been proven to be a favourable basis on which to establish organizational integration (Froese and Goeritz, 2007). This is especially important in the context of an Asian acquirer that is culturally influenced by Confucian values, seeing the human being as the basis of organizational integration (high-context culture). In line with prior research (e.g. Birkinshaw et al., 2000; Froese and Goeritz, 2007), we propose that both human and organizational integration are important for M&A success.

Discussion

Based on a comprehensive literature review and illustrated by drawing on the Putzmeister–Sany case, we developed a conceptual model of how motivations behind M&A decisions and the post-integration approach influence M&A success. Compared to MNEs from industrialized Western countries, Chinese MNEs face a very different institutional environment in their home country (Meyer et al., 2009; Peng et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2009), have different motivations (Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Deng, 2004, 2007; Rui and Yip, 2008) and firm competitive advantages (Buckley et al., 2007; Morck et al., 2008), eventually leading to different post-M&A integration challenges and approaches. Our study suggests that government has a strong influence on Chinese MNEs’ cross-border decisions, not only on state-owned enterprises but also on privately owned firms, depending on their government affiliation level (e.g. Child and Rodrigues, 2005; Lu et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012a, 2012b).

In addition, we identified several key factors that are crucial for a successful post-M&A integration process, such as trust-building actions and strategic fit to facilitate the human as well as organizational integration. If strategic and organizational fit factors are considered before the M&A deal and integration decision, M&A performance can be increased (Gomes et al., 2013).

Theoretical implications

Despite the long history of M&A research (Cartwright and Schoenberg, 2006) there have been few attempts to provide a holistic picture of a pre- and post-M&A process. We extended the models of post-merger integration processes by also integrating and linking them to crucial internationalization drivers and motivation. Combining the M&A and FDI literature sheds a different light on prior research. Our integrative, conceptual model can increase sensitivity to possible pitfalls and give guidance concerning areas of importance while planning an acquisition. Additionally, adding internationalization drivers, motivation and agents (e.g. government) as an antecedent to the conventional pre- and post-M&A stages (Gomes et al., 2013) is particularly important in the context of outward cross-border M&As of EM MNEs.

Nahavandi and Malekzadeh (1988) applied acculturation theory to the M&A context. However, regarding the case of Putzmeister, we would add further specifications and extensions, such as the ‘light-touch integration’, typical of EM MNEs, constituting an interactive outcome of absorptive capacity and cultural influences (Liu and Woywode, 2013). This approach seems to find recent empirical support, as the need for integration decreases when the target country is more industrialized, as in our case (Bauer and Matzler, 2014). The same applies with respect to eclectic theory, where we added the government as a driving force regarding the internationalization decisions of EM MNEs. Government is one of the agents that is pulling the strings and is therefore able to leave an unnoticed footprint on the whole integration phase. Therefore, we call for a more detailed observation of government in the whole process of the internationalization of companies, differing by ownership (Wang et al., 2012b). We feel that this theoretical extension is also relevant for other developing countries, where governments play a vital role in guiding economic development.

We combined knowledge of the strategic management and organizational behaviour streams of research in the M&A context and introduced the FDI literature to gain a new understanding of the agents, processes and decisions involved. Our research shows that post-M&A integration is strongly based on pre-M&A internationalization motivations. Additionally, we explored various factors accounting for the success or failure of cross-border M&As that were in our context, trust-building actions, as well as the strategic fit of the two merging companies. Additionally, the mutual understanding of the two company leaders contributed a great deal to the successful outcome. This leads to the observation that although the cultural distance between China and Germany is high, the common ground between the leaders contributed to a lower demand for structural integration (Bauer and Matzler, 2014; Puranam et al., 2009), offering ‘acquirers an alternate path to achieving coordination that may be less disruptive than structural integration’ (Puranam et al., 2009: 326). In summary, more than one single factor is responsible for successful M&A, so further investigation of its interdependencies is required (Bauer and Matzler, 2014).

Practical implications

We can provide several practical implications for the various stakeholders (policy-makers, managers and employees) involved in Chinese cross-border M&As in industrialized countries.

As for policy implications, the size and frequency of mostly horizontal acquisitions are both increasing. Policy-makers should be prepared for an increase of investment in high-technology-intensive industries rather than the traditional manufacturing sector (Chen and Young, 2010). Additionally, the target industries for investment show a slight shift towards technology, real estate and food after investing almost solely in natural resources in the past (CCTV, 2013). Future M&A deals will involve a higher percentage of private enterprises, which are increasingly encouraged and financially supported by the government, pointing to a ‘golden era’ for their investment abroad (Li, 2013). Chinese private companies have a less complex organizational structure than SOEs, provide more transparency, and have faster decision-making processes and stronger willingness to learn, making them much easier to work with (Liu and Woywode, 2013). However, target firms and countries need to be aware that government affiliation level and motivations behind the investment are not always visible at first glance. Therefore, due to strong government influence in internationalization decisions, we would advise policy-makers to pay increased attention to announcements related to guidelines, such as the goingout strategy or the Five-Year Plan, to deduce possible future development and react more promptly towards these changes. As costs in China continue to rise, global industrial production will be moved to cheaper countries. To counter this threat, the Chinese government’s goals are to move up the value chain through internationalization and create more sustainable competitive advantages by accessing already industrialized markets, technology and brands, as well as enlarging their networks (Buckley et al., 2007). Therefore, in the future, we will see an increase in Chinese cross-border M&A deals targeting companies from industrialized countries. Additionally, future acquisition intentions from private Chinese companies should be less subject to suspicion, because the Chinese government will often not be the majority owner of the firm.

As for managerial implications, the intelligent signalling and cultural intelligence of the Chinese and German sides led to a relatively harmonious integration process without any known major conflicts, contributing to a reduction of employee resistance, which led to better post-acquisition firm performance. Therefore, the dedication and effort of top managers, supervisors and executives contribute significantly to a successful M&A process (Appelbaum et al., 2000), especially if employees perceive support from this cohort (Hildisch et al., 2015). The light-touch integration approach is also greatly beneficial for Western firms insofar as high autonomy is preserved and strategic resources are leveraged (Liu and Woywode, 2013). Additionally, employee expectations are crucial to the success of M&As. Therefore, managers should enquire about these expectations by using specific tools, such as joint activities or employee surveys (Froese et al., 2008). To reduce the likelihood of strikes and demonstrations further, practitioners will have to maintain strong links to unions in order to avoid potential impacts on the firm’s performance. Above all, the timing of communication is essential as any delays in communication foster hostile feelings of employees towards M&As, hampering future communication and integration (Appelbaum et al., 2000).

As for implications for foreign (e.g. German) employees in industrialized countries, the latter should not be too worried about layoffs as Chinese companies prefer light-touch integration, and do not tend to initiate significant changes following a merger. Less organizational integration leads to reduced employee resistance. However, if employee resistance does develop, trust-building actions could reduce it.

As for Chinese policy implications, the growing scepticism towards Chinese M&A deals makes it necessary to restructure the going-out policy and requires paying considerably more attention to the promotion of sustainable OFDI, meaning OFDI that contributes as much as possible to the economic, social and environmental development of host countries and takes place in the context of fair governance, including contracts in natural resources (Sauvant, 2013).

Regarding the practical implications for Chinese companies, we would suggest acquiring firms extending their evaluation criteria for potential target firms by ‘mutual strategic fit’, meaning that the two merging companies should complement each other in terms of industrial sector or strategic goals behind the M&A decision – a less obvious success factor of cross-border M&As. Additionally, it was shown that not only strategic and organizational integration aspects are crucial for the outcome, but also the human side of the merger. Managers should also consider the identified success factor of trust-building actions – measures that have to be planned carefully in advance and must be tailored to the target firm’s organizational and national culture. It was shown how prejudices can multiply anxiety among employees. Positive experiences with Chinese cross-border M&As can improve the image of Chinese companies abroad and mitigate prejudices against Chinese firms and provide opportunities for future M&A decisions in industrialized countries. Findings and recommendations include transparent management communication and participation in decision-making (Bordia et al., 2004; Napier, 1989), stress management training (Matteson and Ivancevich, 1990), and employee assistance programmes (‘town meetings’) before, during and after an acquisition (Fugate et al., 2002).

Limitations and avenues for future research

As our conceptual model mainly draws evidence from one single case in the Chinese–German context, the applicability and generalizability to other country and industry contexts need to be further investigated and empirically supported. However, we suggest that our framework is relevant and can be applied to other emerging economies with strong governmental control and thus higher involvement in internationalization strategies and decisions. Additionally, as our case is based on a privately owned Chinese company, conclusions about other diverse ownership types of companies are difficult to draw. However, as our argument is mainly based on government affiliation level, the de facto ownership type is of minor concern. Still, future research needs to investigate differences and similarities more closely, as Li et al. (2014) have already observed differences between central and local SOEs and OFDI strategies.

Possible avenues for future research are the elaboration and further investigation of a holistic M&A process, as the pre-M&A decision and its antecedents have an influence on various factors during post-merger stages. Developing a generalizable framework that is applicable to other forms of OFDI and other cultural settings could be a valuable area of investigation. Additionally, future research should try to embrace and incorporate further research streams that are relevant to the topic, such as financial economics or the process perspective of the post-merger.

Due to the scarcity of research on a holistic M&A process in general and regarding the context of EM MNEs specifically, we suggest further theoretical investigation and encourage researchers in the field to conduct a large-scale study, providing quantitative support based on our theoretical arguments and case study observations. Furthermore, additional studies have to investigate the double-faced nature of EM MNEs, as parallels between their own driving forces and resources to internationalize and institutional motivations lead to exploitation of these complementarities (Wang et al., 2012b). To provide evidence for the generalizability of our framework, other economies showing a hybrid industrial structure of traditional central planning system and market economy regarding the degree of market imperfection, structural uncertainty and government interference (Wang et al., 2012a) need to be further investigated. In the course of economic development, the question remains whether the role of government institutions remains stable over time or whether entrepreneurship will increase in power in the future (Lu et al., 2011; Yiu et al., 2007).

References

Almor, T., S. Y. Tarba and H. Benjamini, ‘Unmasking integration challenges: The case of Biogal’s acquisition by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries’, International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2009, pp. 32–52.

Appelbaum, S. H., J. Gandell, H. Yortis, S. Proper and F. Jobin, ‘Anatomy of a merger: Behavior of organizational factors and processes throughout the pre–during–post-stages (part 1)’, Management Decision, Vol. 38, No. 9, 2000, pp. 649–662.

Athreye, S. and S. Kapur, ‘Introduction: The internationalization of Chinese and Indian firms – trends, motivations and strategy’, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2009, pp. 209–221.

Bauer, F. and K. Matzler, ‘Antecedents of M&Amp;A success: The role of strategic complementarity, cultural fit, and degree and speed of integration’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2014, pp. 269–291.

Berry, J. W., ‘Acculturation as varieties of adaptation’, in: A. M. Padilla (ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models, and some new findings, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1980, pp. 9–26.

Berry, J. W., ‘Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation’, Applied Psychology, Vol. 46, No. 1, 1997, pp. 5–34.

Birkinshaw, J., H. Bresman and L. Håkanson, ‘Managing the post-acquisition integration process: How the human integration and task integration processes interact to foster value creation’, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2000, pp. 395–425.

Björkman, I., G. K. Stahl and E. Vaara, ‘Cultural differences and capability transfer in cross-border acquisitions: The mediating roles of capability complementarity, absorptive capacity, and social integration’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2007, pp. 658–672.

Boateng, A., W. Qian and Y. Tianle, ‘Cross-border M&Amp;As by Chinese firms: An analysis of strategic motives and performance’, Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 50, No. 4, 2008, pp. 259–270.

Bordia, P., E. Hunt, N. Paulsen, D. Tourish and N. DiFonzo, ‘Uncertainty during organizational change: Is it all about control?’, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2004, pp. 345–365.

Brannen, M. Y. and M. F. Peterson, ‘Merging without alienating: Interventions promoting cross-cultural organizational integration and their limitations’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2009, pp. 468–489.

Buckley, P. J., L. J. Clegg, A. R. Cross, X. Liu, H. Voss and P. Zheng, ‘The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2007, pp. 499–518.

Buckley, P. J., A. R. Cross, H. Tan, L. Xin and H. Voss, ‘Historic and emergent trends in Chinese outward direct investment’, Management International Review, Vol. 48, No. 6, 2008, pp. 715–748.

Cartwright, S. and R. Schoenberg, ‘Thirty years of mergers and acquisitions research: Recent advances and future opportunities’, British Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. S1, 2006, pp. S1–S5.

CCTV, ‘Chinese overseas acquisitions’, 2013. Available at http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2013-10/28/content_17063425.htm (accessed 2 May 2014).

Chen, H. and T.-J. Chen, ‘Network linkages and location choice in foreign direct investment’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 29, No. 3, 1998, pp. 445–467.

Chen, X.-P. and C. C. Chen, ‘On the intricacies of the Chinese guanxi: A process model of guanxi development’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2004, pp. 305–324.

Chen, Y. Y. and M. N. Young, ‘Cross-border mergers and acquisitions by Chinese listed companies: A principal–principal perspective’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2010, pp. 523–539.

Child, J., ‘China and international business’, in: A. M. Rugman and T. L. Brewer (eds), Oxford Handbook of International Business, New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 648–686.

Child, J., S. H. Ng and C. Wong, ‘Psychic distance and internationalization: Evidence from Hong Kong firms’, International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2002, pp. 36–56.

Child, J. and S. B. Rodrigues, ‘The Internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for theoretical extension?’, Management and Organization Review, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2005, pp. 381–410.

CNN, ‘China’s richest man hopes to join the political elite’, 29 September 2011. Available at http://edition.cnn.com/2011/09/29/business/china-liang-wengen-communist-party/ (accessed 25 April 2014).

CNN Money, ‘Fortune Global 500 2013’, 2013. Available at http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/global500/2013/full_list/ (accessed 2 April 2014).

Cui, L. and F. Jiang, ‘Behind ownership decision of Chinese outward FDI: Resources and institutions’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2010, pp. 751–774.

Cui, L. and F. Jiang, ‘State ownership effect on firms’ FDI ownership decisions under institutional pressure: A study of Chinese outward-investing firms’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 43, No. 3, 2012, pp. 264–284.

Datta, D. K., ‘Organizational fit and acquisition performance: Effects of post-acquisition integration’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 12, No. 4, 1991, pp. 281–297.

Dauber, D., ‘Opposing positions in M&Amp;A research: Culture, integration and performance’, Cross-Cultural Management: An International Journal, Vol. 19, No. 3, 2012, pp. 375–398.

Deng, P., ‘Outward investment by Chinese MNCs: Motivations and implications’, Business Horizons, Vol. 47, No. 3, 2004, pp. 8–16.

Deng, P., ‘Investing for strategic resources and its rationale: The case of outward FDI from Chinese companies’, Business Horizons, Vol. 50, No. 1, 2007, pp. 71–81.

Deng, P., ‘Why do Chinese firms tend to acquire strategic assets in international expansion?’, Journal of World Business, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2009, pp. 74–84.

DiFonzo, N. and P. Bordia, ‘A tale of two corporations: Managing uncertainty during organizational change’, Human Resource Management, Vol. 37, Nos. 3–4, 1998, pp. 295–303.

DIHK, ‘Fachkraft Chef’ gesucht!, DIHK-Report zur Unternehmensnachfolge 2011, 2011. Available at www.leipzig.ihk.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Dokumente/EuU/DIHK-Nachfolgereport_2011.pdf (accessed 17 March 2014).

Dunning, J. H., ‘Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: A search for an eclectic approach’, in: B. Ohlin, P.-O. Hesselborn and P. M. Wijkman (eds), The International Allocation of Economic Activity: Proceedings of a Nobel Symposium Held at Stockholm, London: Macmillan, 1977, pp. 395–418.

Dunning, J. H., Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy, Reading, MA, and Menlo Park, CA: Addison Wesley, 1993.

Dunning, J., ‘Comment on Dragon multinationals: New players in 21st century globalization’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2006, pp. 139–141.

Dunning, J. H. and S. M. Lundan, Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2008.

Dunning, J. and R. Narula (eds), Foreign Direct Investment and Governments: Catalysts for Economic Restructuring London: Routledge, 1996.

Dupasquier, C. and P. N. Osakwe, ‘Foreign direct investment in Africa: Performance, challenges, and responsibilities’, Journal of Asian Economics, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2006, pp. 241–260.

Fischer, H., ‘Die Betonmischer: Die Kräfteverhältnisse zwischen West und Ost verschieben sich: Warum der chinesische Konzern Sany den deutschen Betonpumpenbauer Putzmeister übernommen hat’, Impulse, No. 3, 2012, pp. 40–47.

Fortanier, F. and R. v. Tulder, ‘Internationalization trajectories – a cross-country comparison: Are large Chinese and Indian companies different?’, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2009, pp. 223–247.

Froese, F. J. and L. E. Goeritz, ‘Integration management of Western acquisitions in Japan’, Asian Business and Management, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2007, pp. 95–114.

Froese, F. J., Y. S. Pak and L. C. Chong, ‘Managing the human side of cross-border acquisitions in South Korea”, Korean Issue, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2008, pp. 97–108.

Fugate, M., A. J. Kinicki and C. L. Scheck, ‘Coping with an organizational merger over four stages’, Personnel Psychology, Vol. 55, No. 4, 2002, pp. 905–928.

Gomes, E., D. N. Angwin, Y. Weber and S. Y. Tarba, ‘Critical success factors through the mergers and acquisitions process: Revealing pre- and post-M&Amp;A connections for improved performance’, Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 55, No. 1, 2013, pp. 13–35.

Guillén, M. F. and E. García-Canal, ‘The American model of the multinational firm and the new multinationals from emerging economies’, Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2009, pp. 23–35.

Haspeslagh, P. C. and D. B. Jemison, Managing Acquisitions: Creating Value through Corporate Renewal, New York: Free Press, 1991.

Hildisch, A. K., F. J. Froese and Y. S. Pak, ‘Employee responses to a cross-border acquisition in South Korea: The role of social support from different hierarchical levels’, Asian Business and Management, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2015, pp. 327–347.

Hirn, W., ‘Neue Herren aus China: Wie sich Putzmeister und Sany die Welt aufteilen’, 2013. Available at www.manager-magazin.de/unternehmen/artikel/a-900147.html (accessed 20 January 2015).

Hitotsuyanagi-Hansel, A., F. J. Froese and Y. S. Pak, ‘Lessening the divide in foreign subsidiaries: The influence of localization on the organizational commitment and turnover intention of host country nationals’, International Business Review, No. 25, 2016, pp. 569–578.

Hong, E. and L. Sun, ‘Dynamics of internationalization and outward investment: Chinese corporations’ strategies’, China Quarterly, No. 187, 2006, pp. 610–634.

Jöns, I., F. J. Froese and Y. S. Pak, ‘Cultural changes during the integration process of acquisitions: A comparative study between German and German–Korean acquisitions’, International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 31, No. 5, 2007, pp. 591–604.

Klawitter, N. and W. Wagner, ‘Götterdämmerung: Die Chinesen übernehmen den Betonpumpenhersteller Putzmeister und damit erstmals ein deutsches Unternehmen von Weltgeltung. Es dürfte nicht das letzte gewesen sein.’, Der Spiegel, No. 6, 2012, pp. 68–69.

Klooß, K., ‘Putzmeister-Chef Norbert Scheuch: Die Globalisierung trägt uns weg von Deutschland’, 2013. Available at www.manager-magazin.de/unternehmen/industrie/a-889073-2.html (accessed 18 August 2014).

Klossek, A., B. M. Linke and M. Nippa, ‘Chinese enterprises in Germany: Establishment modes and strategies to mitigate the liability of foreignness’, Focus on China Special Section, Vol. 47, No. 1, 2012, pp. 35–44.

Kumar, N., ‘How emerging giants are rewriting the rules of M&Amp;A’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 87, No. 5, 2009, pp. 115–121.

Larsson, R. and S. Finkelstein, ‘Integrating strategic, organizational, and human resource perspectives on mergers and acquisitions: A case survey of synergy realization’, Organization Science, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1999, pp. 1–26.

Li, J., ‘Overseas investment set for “golden era” ’, 2013. Available at http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2013-12/12/content_17170070.htm (accessed 2 May 2014).

Li, J., ‘State planners relax outward investment regulations’, 2014. Available at http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2014-01/09/content_17226582.htm (accessed 2 May 2014).

Li, M. H., L. Cui and J. Lu, ‘Varieties in state capitalism: Outward FDI strategies of central and local state-owned enterprises from emerging economy countries’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 45, No. 8, 2014, pp. 980–1004.

Liu, Y. and M. Woywode, ‘Light-touch integration of Chinese cross-border M&Amp;A: The influences of culture and absorptive capacity’, Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 55, No. 4, 2013, pp. 469–483.

Lu, J., X. Liu and H. Wang, ‘Motives for outward FDI of Chinese private firms: Firm resources, industry dynamics, and government policies’, Management and Organization Review, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2011, pp. 223–248.

Luo, Y. and R. L. Tung, ‘International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2007, pp. 481–498.

Luo, Y., Q. Xue and B. Han, ‘How emerging market governments promote outward FDI: Experience from China’, Journal of World Business, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2010, pp. 68–79.

Makino, S., C.-M. Lau and R.-S. Yeh, ‘Asset-exploitation versus asset-seeking: Implications for location choice of foreign direct investment from newly industrialized economies’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 33, No. 3, 2002, pp. 403–421.

Matteson, M. T. and J. M. Ivancevich, ‘Merger and acquisition stress: Fear and uncertainty at mid-career’, Prevention in Human Services, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1990, pp. 139–158.

Meyer, K. E., S. Estrin, S. K. Bhaumik and M. W. Peng, ‘Institutions, resources, and entry strategies in emerging economies’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2009, pp. 61–80.

Ministry of Commerce, Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment, Beijing: Ministry of Commerce, 2010.

Ministry of Commerce, ‘MOFCOM holds press conference on CSR of Chinese companies operating abroad’, 2013. Available at http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/zt_review2013/column3/201401/20140100455061.shtml (accessed 2 May 2014).

Ministry of Commerce, Joint Report on Statistics of China’s Outbound FDI 2013, 2014. Available at http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/newsrelease/significantnews/201409/20140900727958.shtml (accessed 16 June 2016).

Morck, R., B. Yeung and M. Zhao, ‘Perspectives on China’s outward foreign direct investment’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2008, pp. 337–350.

Nahavandi, A. and A. R. Malekzadeh, ‘Acculturation in mergers and acquisitions’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 13, No. 1, 1988, pp. 79–90.

Napier, N. K., ‘Mergers and acquisitions, human resource issues and outcomes: A review and suggested typology’, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 26, No. 3, 1989, pp. 271–290.

Narula, R., ‘Do we need different frameworks to explain infant MNEs from developing countries?’, Global Strategy Journal, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2012, pp. 188–204.

OECD, ‘FDI financial flows by partner country BMD4’, 2014. Available at www.oecd.org/corporate/mne/statistics.htm (accessed 16 June 2016).

Peng, M. W., D. Y. L. Wang and Y. Jiang, ‘An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 39, No. 5, 2008, pp. 920–936.

Puranam, P., H. Singh and S. Chaudhuri, ‘Integrating acquired capabilities: When structural integration is (un)necessary’, Organization Science, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2009, pp. 313–328.

Rodrigues, S. and J. Child, ‘Co-evolution in an institutionalized environment’, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 40, No. 8, 2003, pp. 2137–2162.

Rui, H. and G. S. Yip, ‘Foreign acquisitions by Chinese firms: A strategic intent perspective’, Journal of World Business, Vol. 43, No. 2, 2008, pp. 213–226.

Sarala, R. M., ‘The impact of cultural differences and acculturation factors on post-acquisition conflict’, Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2010, pp. 38–56.

Sauvant, K. P., Challenges for China’s outward FDI, 2013. Available at http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2013-10/31/content_17070440.htm (accessed 30 April 2014).

Seo, M.-G. and N. S. Hill, ‘Understanding the human side of merger and acquisition: An integrative framework’, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2005, pp. 422–443.

Shenkar, O., ‘Cultural distance revisited: Towards a more rigorous conceptualization and measurement of cultural differences’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 32, No. 3, 2001, pp. 519–535.

Simon, H., ‘Sany-Putzmeister takeover – a sign of Mittelstand deals to come’, 2012. Available at http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2012/02/02/sany-putzmeister-a-sign-of-mittelstand-deals-to-come/?Authorised=false (accessed 18 August 2014).

Stahl, G. K. and A. Voigt, ‘Do cultural differences matter in mergers and acquisitions? A tentative model and examination’, Organization Science, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2008, pp. 160–176.

UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2006: FDI from Developing and Transition Economies: Implications for Development, New York: United Nations, 2006.

UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2013: Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development, New York: United Nations, 2013.

UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2015: Reforming International Investment Governance, New York: United Nations, 2015.

UNCTAD, World Investment Report 2016: Investor Nationality: Policy Challenges, New York: United Nations, 2016.

Vaara, E., R. M. Sarala, G. K. Stahl and I. Björkman, ‘The impact of organizational and national cultural differences on social conflict and knowledge transfer in international acquisitions’, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2012, pp. 1–27.

Von Leesen, G., ‘Putzmeister in Kommunistenhand’, 2012. Available at www.kontextwochenzeitung.de/wirtschaft/45/putzmeister-in-kommunistenhand-1192.html (accessed 18 August 2014).

Wang, C., J. Hong, M. Kafouros and A. Boateng, ‘What drives outward FDI of Chinese firms? Testing the explanatory power of three theoretical frameworks’, International Business Review, vol. 21, no. 3, 2012a, pp. 425–438.

Wang, C., J. Hong, M. Kafouros and M. Wright, ‘Exploring the role of government involvement in outward FDI from emerging economies’, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 43, no. 7, 2012b, pp. 655–676.

Weber, Y. and S. Y. Tarba, ‘Exploring integration approach in related mergers: Post-merger integration in the high-tech industry’, International Journal of Organizational Analysis, Vol. 19, No. 3, 2011, pp. 202–221.

Weber, Y., S. Y. Tarba and A. Reichel, ‘International mergers and acquisitions performance revisited: The role of cultural distance and post’, Advances in Mergers and Acquisitions, Vol. 8, 2009, pp. 1–17.

Weber, Y., S. Y. Tarba and A. Reichel, ‘A model of the influence of culture on integration approaches and international mergers and acquisitions performance’, International Studies of Management and Organization, Vol. 41, No. 3, 2011, pp. 9–24.

Yang, X., Y. Jiang, R. Kang and Y. Ke, ‘A comparative analysis of the internationalization of Chinese and Japanese firms’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2009, pp. 141–162.

Yiu, D. W., C. Lau and G. D. Bruton, ‘International venturing by emerging economy firms: The effects of firm capabilities, home country networks, and corporate entrepreneurship’, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2007, pp. 519–540.

Zaheer, S., ‘Overcoming the liability of foreignness’, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2, 1995, pp. 341–363.

Zhang, J., C. Zhou and H. Ebbers, ‘Completion of Chinese overseas acquisitions: Institutional perspectives and evidence’, International Business Review, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2011, pp. 226–238.

Zhang, X. and K. Daly, ‘The determinants of China’s outward foreign direct investment’, Emerging Markets Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, 2011, pp. 389–398.

Zhang, Y., China’s Emerging Global Businesses: Political Economy and Institutional Investigations, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.