9

How Do Communication and Cultural Differences Explain Post-Merger Identification?

Evidence from two merged dairy firms

Introduction

Organizations frequently use mergers and acquisitions (M&As) as a strategy to expand and improve their competitive advantage (Makri, Hitt and Lane, 2010). However, M&As often fail to meet their objectives (Dyer, Kale and Singh, 2004; Seo and Hill, 2005). Scholars increasingly attribute poor M&A performance to issues that arise during the integration phase (Cording, Christmann and King, 2008; Epstein, 2005). Birkinshaw (1999: 34; italics added), for example, concludes that ‘human integration’, concerned primarily with ‘the process of generating satisfaction – and ultimately a shared identity – among the employees of the merged company’, is an important determinant of overall M&A success.

The extent to which employees of the merged company identify with the newly merged organization (i.e. post-merger identification) influences employees’ willingness to strive for organizational goals, to stay with the organization, to spread a positive image of the organization and to cooperate with other organizational members (Bartels, Douwes, De Jong and Pruyn, 2006). Especially in times of considerable organizational restructuring (such as during post-merger integration), these aspects are of crucial importance. In this study, we therefore aim to provide more insight into the factors that explain the level of post-merger identification.

Although research on post-merger identification has flourished (Van Dick, Ullrich and Tissington, 2006; Van Knippenberg, Van Knippenberg, Monden and De Lima, 2002; Zaheer, Schomaker and Genc, 2003), several questions remain unanswered. First, we know little about how different pre-merger organizational cultures affect post-merger identification. Both researchers and practitioners frequently refer to cultural differences as causes of disappointing outcomes in domestic and international cooperation (Larsson and Lubatkin, 2001). Previous research has already illustrated that organizational identification (Ullrich and Van Dick, 2007) and organizational culture (Teerikangas, 2007) are related, and that both are of crucial importance in post-merger integration times (Kroon, Noorderhaven and Leufkens, 2009). However, until now cultural differences and post-merger identification have been mostly studied in isolation from each other, or, at the other extreme, the concepts have been used interchangeably (Kroon et al., 2009: 22).

Second, we need to know more about the role of employee communication in explaining the relationship between cultural differences and post-merger identification. Prior studies have identified that intensive communication is the key to a successful integration of two clashing cultures (DiGeorgio, 2002). Furthermore, employee communication has been shown to influence (expected) post-merger identification (Bartels et al., 2006). But although scholars agree on the crucial importance of proper communication in the post-merger integration process (Clampitt, DeKoch and Cashman, 2000; Epstein, 2004; Sonenshein, 2010), the literature on its specific influence has remained scarce (Allatta and Singh, 2011).

By conducting a large-scale study of two dairy firms in the Netherlands, we contribute to the literature on ‘human factors’ in post-merger integration in several ways. First, our empirical findings show that both the perceived quality of communicated information (‘merger communication’) and the general communication climate (Bartels et al., 2006; Bartels, Pruyn, De Jong and Joustra, 2007) are important determinants of post-merger identification. Moreover, we find that the perceived communication climate mediates the relationship between merger communication and post-merger identification. Second, we observe that merger communication moderates the negative relation between perceived cultural differences and post-merger identification. Finally, our study provides managers and practitioners engaged in M&As with some specific knowledge on how communication may help to make M&As more successful.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The section below develops a theoretical framework, introduces the key variables of the study, and advances testable hypotheses. The next section describes our research design and the operationalization of the constructs. We test our hypotheses using questionnaire data from a large-scale merger between two dairy firms in the Netherlands. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the study’s main theoretical and managerial implications as well as suggestions for future research opportunities.

Theoretical background

Post-merger identification and cultural differences

Social identification reflects the extent to which the self is defined in collective terms (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). It implies a ‘merging’ of the self and the group in a psychological sense. However, not all social groups are emotionally significant all the time. Self-categorization theory, seen by Hogg and Terry (2000) as a development of social identity theory, articulates the principles according to which different social identities become salient in a given situation (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher and Wetherell, 1987). The core element of self-categorization theory, according to Van Dick et al. (2006), is that an individual’s social identity is not uniformly predictive of his or her behaviour. In other words, which aspect of one’s identity is influential in a given situation is dependent on the context (e.g. a merger or an acquisition) and the group’s salience in that context.

Applying social identity theory to an M&A context, we can define post-merger identification as the perception of oneness with or belongingness to the newly merged organization, where the individual defines him- or herself in terms of this organization (Mael and Ashforth, 1992). According to social identity theory and self-categorization theory, M&As may be perceived as a threat to the stability and continuation of employees’ pre-merger organizational identities (Bartels et al., 2006). There are also practical examples of mergers that failed because of ‘us versus them’ dynamics that prevail if employees do not relinquish their ‘old’ identities (Hogg and Terry, 2000). Terry and Callan (1998) argue that, because of the rejection of a new post-merger identity, negative responses and feelings toward the employees of the other organization may jeopardize the success of the merger. On the other hand, when employees do identify with the newly merged organization this is found to have positive effects on merger integration processes and outcomes (Van Knippenberg et al., 2002; Terry, Carey and Callan, 2001; Seo and Hill, 2005). When organization members have a sense of belonging to or feel connected with the post-merger organization this results in more support for and cooperation in the merger integration process.

Similar to the ‘us versus them’ dynamics regarding the pre-merger organizational identities, differences in pre-merger organizational cultures can be seen as the root cause of many problems in M&A integration (Zaheer et al., 2003). However, culture and identity are rarely examined together (Kroon et al., 2009) and most previous work has focused on the theoretical relations between both concepts (Hatch and Schultz, 1997, 2000, 2002). More recently, Ravasi and Schultz (2006) and Kroon et al. (2009) have conducted empirical studies on the relationship between culture and identity. Ravasi and Schultz (2006) found that, when confronted with change (such as a merger or an acquisition), organizational culture supplies employees with cues for reinterpreting the defining characteristics of their organization and for making sense of their new organization’s identity. In line with this, Kroon et al. (2009) found that post-merger identification mediates the relationship between organizational cultural differences and employees’ willingness to cooperate.

Employee communication

M&As are associated with many unknowns and ambiguities, which are generally perceived as uncomfortable by employees (Corley and Gioia, 2004). In an M&A context, several sources of employee uncertainty exist. First, uncertainty about the consequences of the M&A including possible layoffs and new future roles for employees causes stress among organizational members. Second, organizational members are often uncertain about the continuation of their pre-merger organization in the post-merger culture and identity (Van Knippenberg et al., 2002) and feel anxiety about losing their identity and organizational culture. Finally, according to Schweiger and DeNisi (1991), not the change itself but the means of communicating about it may cause stress and uncertainty.

Proper communication helps organizational members to cope with the experienced uncertainty, and thus reduce the negative outcomes often associated with M&As (Schweiger and DeNisi, 1991). Prior literature has generally acknowledged the importance of accurate and relevant communication during M&A processes (Ager, 2011; Appelbaum, Gandell, Yortis, Proper and Jobin, 2000; Sonenshein, 2010). Epstein (2004), for example, points to overcommunication as a major driver of success in post-merger integration

According to Smidts, Pruyn and Van Riel (2001), employee communication can be divided into two components: ‘merger communication’ (i.e. the content and quality of the information that is communicated to employees) and ‘communication climate’ (i.e. the overall quality of communication in the organization as a whole). In their study, Smidts et al. (2001) distinguish between communication about relevant organizational issues and communication about an employee’s personal role in the organization. In an M&A context, relevant organizational issues include goals, objectives and achievements of the merger (Smidts et al., 2001) as well as possible layoffs and other important consequences of the M&A (Papadakis, 2005). The latter type of communication implies what is expected of organizational members in the future with respect to their work and their contribution to merger success.

Whereas most previous work has focused on management and top-down communication about the merger, and because few studies have addressed the specific role of communication during post-merger integration (Bartels et al., 2006), we examine both merger communication and the perceived communication climate in relation to employees’ post-merger identification. The essence of our theoretical background is captured in the following research question:

How do perceived cultural differences, communication climate and merger communication influence employees’ post-merger identification?

Hypotheses development

Cultural differences and post-merger identification

Although positive effects – such as the benefits of increased diversity within the organization (Vaara, 1999) – are also found, the negative effects of cultural differences on organizational identification, including inter-group bias, are more profound. Inter-group bias means that members have a preference for the in-group over the out-group, and social identity theory asserts that certain contexts in particular provide ground for comparison between these groups (Ashforth and Mael, 1989; DeNisi and Shin, 2005). M&As in which organizational cultural differences are perceived constitute such a context in which employees’ own organization is compared with and favoured over the partner organization. This is expected to decrease the identification with the newly merged organization, as members identify less with the post-merger organization since this entity comprises both the members’ own and the more negatively perceived partner organization. This is in line with the findings of Kroon et al. (2009), who concluded that perceived organizational cultural differences indirectly influence behavioural intentions, such as willingness to cooperate in the merger through the more explicit organizational identification process. Therefore, we propose that perceived cultural differences have a negative effect on post-merger identification.

Employee communication and post-merger identification

In earlier research, employee communication has been found to be related to organizational identification (Scott, 1997; Smidts et al., 2001). According to Smidts et al. (2001), the adequacy of information about both employees’ personal roles and the organization as well as a positive communication climate strengthen employees’ identification with the post-merger organization. Bartels et al. (2006, 2007) also found evidence for the existence of this relationship in an M&A context. Whereas these authors examined the expected identification with the post-merger organization, we also expect this to hold for employees’ actual identification with the post-merger organization.

As stated before, the communication climate consists of employees’ perceptions about the quality of information in the organization (Smidts et al., 2001; Bartels et al., 2006) and the relevant dimensions of communication climate in a merging organization are employees’ feelings of supportiveness, openness in communication, and participation in decision-making (Bartels et al., 2006). These aspects constitute some individual needs that employees would like to have fulfilled in their organization. Since the number of individual needs that are satisfied within the organization are positively associated with the level of organizational identification (March and Simon, 1958), we propose that as employees have a higher feeling of supportiveness, of having voice and of being taken seriously in the newly merged organization, the strength of their identification with the post-merger organization will increase. Thus, based on the findings of Smidts et al. (2001) and Bartels et al. (2006), we develop the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The more positive employees’ perceptions of the communication climate, the more they will identify with the post-merger organization.

In addition to the effect of the communication climate on post-merger identification, Smidts et al. (2001) found that employees’ perception of the quality of information about their personal roles and about the organization is positively related to organizational identification. Bartels et al. (2006) examined the role of communication in a merger context and concluded that the more positive employees’ perceptions of the communication about the merger, the more organizational members identify with the post-merger organization. Hence, we argue that a positive perception of the content and quality of communication about the merger has a positive effect on post-merger identification.

Hypothesis 3: The more positive employees’ perceptions of merger communication, the more they will identify with the post-merger organization.

According to Smidts et al. (2001), communication climate mediates the effect of the perceived quality of information about employees’ personal roles and about the organization on organizational identification, since communicating higher-quality information to employees leads to more positive employee perception of the communication climate of their organization. We also expect this finding to hold in an M&A context. In other words, better content and quality of information about the merger improves the perceived communication climate of the merged organization. As a result, employees’ post-merger identification will increase. Thus, we expect that a perceived communication climate mediates the relationship between merger communication and identification with the post-merger organization.

Hypothesis 4: The positive effect of employees’ perceived merger communication on post-merger identification is mediated by the communication climate.

Cultural differences, merger communication and post-merger identification

Because of the salience of the in-group and the out-group boundary in an M&A setting, employees tend to engage more in inter-group cognitions, such as in-group favouritism and stereotyping (DeNisi and Shin, 2005; Ashforth and Mael, 1989). When organizational cultural differences are perceived, the prevalence of inter-group cognitions and the level of in-group favouritism in comparison with the out-group, the merging partner, will be exacerbated (Cartwright and Cooper, 1993; Haunschild, Moreland and Murrell, 1994). These inter-group cognitions tend to cause negative outcomes, including out-group discrimination, distrust of the merging partner, tensions and in-group rumours. In addition, inter-group cognitions tend to motivate non-cooperative behaviour (DeNisi and Shin, 2005). However, employee communication can compensate for these negative attitudes and behaviours. Schweiger and DeNisi (1991) point out that it is not so much the organizational change that is stressful for organizational members but rather how (well) that change is communicated. Moreover, realistic communication can help employees cope with the uncertainty as a result of a merger or an acquisition. According to Jimmieson, Terry and Callan (2004), the information supply about (forthcoming) organizational changes may help to reduce employees’ feelings of uncertainty and threats caused by these changes. In other words, the appropriate communication policy is vital to bridge the differences in culture (Appelbaum et al., 2000; Papadakis, 2005). These issues mainly deal with the content and quality of communication about the merger (i.e. merger communication). Therefore, we argue that positive perceptions of merger communication weaken the negative effect of perceived cultural differences on post-merger identification.

Methods

Below, we describe how we test the developed hypotheses using data from a large-scale study of two merged dairy firms in the Netherlands.

Research setting

We studied the merger of two Dutch dairy firms. One pre-merger company was mainly located in the north of the Netherlands, whereas the other company’s plants and offices were located in the south and east. Mergers are quite common in the dairy industry. The merger we studied was initiated by the dairy farmers, and in December 2007 the managements of both dairy cooperatives announced their intentions to merge. The European Commission started reviewing the merger in the beginning of 2008, a process that continued until the end of the year, when the Commission approved the merger under the condition that the new cooperative would divest some of its fresh dairy activities in the Netherlands. The official merger took place on 30 December 2008, resulting in a multinational dairy cooperative. This company is now located in twenty-five countries and provides dairy-based products to more than one hundred countries around the world. In 2011, sales amounted to over €9 billion. The company employs around 19,000 people.

Sample and data collection procedure

We first conducted some exploratory interviews with the Director Corporate Strategy and the Director Human Resources to gain some knowledge about the merger context and the phases and key events of the merger integration process. Next, our primary data was collected using a self-administered questionnaire, three years and five months after the implementation of the merger. Existing scales from previous research were used to measure the core variables of our study. Our sample consists of management and employees of the division that is most strongly affected by the merger. This sample is further restricted to contain only those organization members who were present in one of the pre-merger companies. The stratified systematic sampling technique is used to ensure that employees from each of the hierarchical levels and pre-merger organizations are represented proportionally within the sample.

A total of 411 surveys were distributed, with 142 sent to employees working at headquarters and 269 sent to employees working at the selected plants. Employees working at headquarters received an online questionnaire, whereas employees working in the plants received a hard-copy version. We assured both groups of the confidentiality of the findings and the anonymity of the respondents. Company involvement and salience of the topic were highlighted by adding a personal note from the Director Human Resources of the division. Ultimately, 142 surveys were returned (a response rate of 35 per cent). This is sufficient to obtain reliable results from statistical analyses, based on Hinkin’s (1998) norm of approximately 150 responses.

The final type of data collected in this study consists of secondary data. It includes documents of the merger, such as communication material that was sent out (e.g. presentations, emails and letters), the annual reports of the merged company, the results of the culture research done by McKinsey in the pre-merger phase, and a document about the presentation of the new logo and the development of a new strategy. Furthermore, access to personnel databases helped in selecting a sample for the survey. These secondary data sources were primarily used for triangulation, for understanding the merger context and key events during the post-merger integration process.

Variables

The questionnaire contained several variables that are not relevant for the present context. We will describe only those scales that match the present theoretical framework. The Appendix presents the multi-item survey constructs that were used in this study, together with their factor loadings and Cronbach’s alpha for scale reliability.

Post-merger identification, our dependent variable, is measured by five items derived from Mael and Ashforth’s (1992) identification scale. These items were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 ‘completely disagree’ to 5 ‘completely agree’). Cronbach’s alpha for the post-merger identification scale equals 0.87, which indicates good scale reliability.

The extent to which employees perceive organizational cultural differences is measured by using a seven-item Likert-type scale based on Kroon et al. (2009). The organizational cultural differences are calculated by taking the sum of the absolute differences between employees’ perceived culture of their own pre-merger organization and the perceived culture of the ‘new’ post-merger organization for all seven items included in the scale. The reliability of the measure can be considered satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.77). However, we can also argue that this is a formative, rather than a reflective, scale, in which case Cronbach’s alpha is not a relevant measure (Diamantopoulos and Siguaw, 2006).

To measure the communication climate at the merged company, a nine-item Likert-type scale developed by Bartels et al. (2006) is used. Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with such statements as ‘Generally speaking, everyone is honest with one another’ and ‘Colleagues genuinely listen to me when I say something’. Seven items remain after a factor analysis. The scale is reliable, as Cronbach’s alpha equals 0.85.

The initial scale for merger communication is an eighteen-item, five-point Likert-type scale (1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 ‘strongly agree’) that measures employees’ perceptions of the communication about the merger. This measure is based on the scale of Bartels et al. (2006). After a factor analysis, four items were deleted and the scale demonstrates excellent scale reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.95).

Finally, several control variables are included in this study. Gender is included as a dummy variable (0 ‘male’ and 1 ‘female’), as well as employees’ pre-merger organization. In addition, age and tenure are included, with both expressed in years. Furthermore, we asked whether the respondent had changed location due to the merger. In addition to this question, the variable integration impact is measured with five items based on Shrivastava (1986), to assess the extent to which employees have been impacted by the merger. The scale can be considered reliable (Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

Analysis

We first conducted a confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 6.0 (Byrne, 2001) to check for convergent and discriminant validity. As the data are not normally distributed, principal axis factoring is preferred (Costello and Osborne, 2005). The rotation method used is oblique rotation, since this allows factors to correlate – it treats constructs as dependent on each other – and provides the most accurate solution in a factor analysis. Subsequently, we performed hierarchical multiple regression analysis to examine post-merger identification. Before calculating the interaction term used to test Hypothesis 5, we mean-centred the variables involved (Aiken and West, 1991).

Results

Reliability and validity

All multi-item constructs display satisfactory levels of reliability, as can be seen from the Cronbach’s alphas in the Appendix, which range from 0.81 to 0.95. Convergent validity is examined by looking at the item factor loadings (see Appendix). All of the standardized item loadings (λ) for the multi-item constructs are above the cut-off value of 0.50 (Hildebrandt, 1987), supporting convergent validity.

To assess discriminant validity, we performed a series of chi-square difference tests on the factor correlations. It is particularly important that discriminant validity would be achieved between the employee communication constructs, since these constructs were rather highly correlated. Therefore, we constrained the correlation between these constructs to 1.0 and then performed a chi-square difference test on the values obtained for the unconstrained and the constrained model. The significant difference in chi-square (Δ χ2 = 240.80, Δ df = 1, p < 0.01) between the unconstrained model and the constrained model, where we constrained the correlation between communication climate and merger communication to 1.0, indicates that discriminant validity is achieved. Moreover, the differences in goodness-of-fit and comparative-fit indexes between the constrained and unconstrained models are moderately large (Δ GFI = 0.08, Δ CFI = 0.09), again providing evidence for sufficient discriminant validity.1

Descriptive statistics

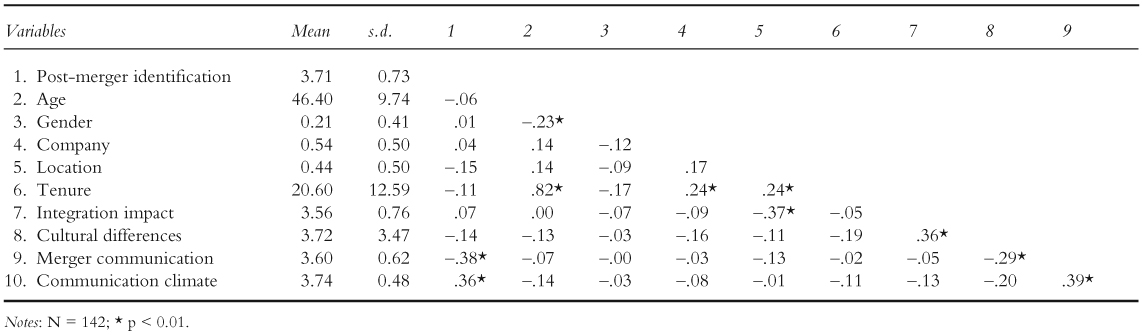

The means, standard deviations and intercorrelations of the variables used in this study are presented in Table 9.1.

Means of the perceived quality and content of communication regarding the merger, the perceived communication climate and the level of identification with the post-merger organization are all above the midpoint of a five-point Likert-type scale (means are 3.60, 3.74 and 3.71, respectively). Of the survey respondents, 80 per cent are men, whereas 20 per cent are women. The mean age of these respondents is forty-six years and, on average, employees had worked for more than twenty years at one of the pre-merger organizations. Both pre-merger organizations are represented approximately equally and the percentage of respondents that changed location after the merger is 56 per cent. This high percentage might be due to the fact that all employees working at headquarters, 43 per cent of the respondents, changed location after the merger as both of the previous headquarters were closed and replaced by a new headquarters.

Testing the hypotheses

First, we examine the relationship between post-merger identification and the control variables. From the results in Table 9.2 (Model 1), we can conclude that employees who had to change location as a result of the merger identify less with the post-merger organization.

To examine the effect of organizational cultural differences on post-merger identification, we introduced this variable in Model 2. The additional variance accounted for by the cultural differences variable is significant (Δ R2 = 0.04, p < 0.05). The coefficient of the cultural differences variable in Model 2 is significant and negative (b = –0.04, p < 0.05), providing support for Hypothesis 1. This is consistent with the findings of Kroon et al. (2009), who illustrate that the extent to which organizational members perceive cultural differences between organizations is negatively related to post-merger identification. However, as we will illustrate below, this result does not hold across all specifications of the model.

In order to test Hypotheses 2 and 3, the variables communication climate and merger communication were added to Model 3. Since a positive and significant effect is found for communication climate (b = 0.35, p < 0.01) as well as for merger

Table 9.1 Descriptive statistics and correlations matrix

communication (b = 0.25, p < 0.05), it can be argued that employee communication is an important determinant in explaining post-merger identification. More specifically, a more positive communication climate at the post-merger organization as perceived by employees results in higher levels of post-merger identification. In other words, as employees have higher feelings of supportiveness, of having a voice and of being taken seriously in the newly merged organization, they will identify more strongly with the post-merger organization. This is in line with the studies of Smidts et al. (2001) and Bartels et al. (2006, 2007), who found – in both a non-merger and a merger context – that as employees perceive the communication climate of their organization as more positive, they identify more strongly with that organization.

Table 9.2 Results of multiple regression analysis for post-merger identification

| Variables | Post-merger identification | Post-merger identification | Post-merger identification | Post-merger identification |

| Intercept | 4.10** (0.64) | 3.82** (0.66) | 1.91* (0.83) | 2.23** (0.82) |

| Age | –0.00 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.00 (0.01) |

| Gender | –0.06 (0.15) | –0.05 (0.15) | –0.02 (0.14) | –0.05 (0.14) |

| Company | 0.21† (0.12) | 0.17 (0.12) | 0.19 (0.12) | 0.13 (0.12) |

| Location | –0.23† (0.13) | –0.22† (0.13) | –0.15 (0.13) | –0.12 (0.13) |

| Tenure | –0.00 (0.01) | –0.01 (0.01) | –0.01 (0.01) | –0.01 (0.01) |

| Integration impact | –0.03 (0.08) | 0.05 (0.09) | 0.09 (0.09) | 0.12 (0.09) |

| Main effects | ||||

| Cultural differences | –0.04* (0.02) | –0.02 (0.02) | –0.01 (0.02) | |

| Merger communication | 0.25* (0.11) | 0.21* (0.10) | ||

| Communication climate | 0.35** (0.12) | 0.29* (0.12) | ||

| Interaction effect | ||||

| Cultural differences × merger communication | 0.06** (0.02) | |||

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.28 |

| Δ R2 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.31 | |

| Δ F | 4.31 | 10.27 | 6.83 | |

Notes:

N = 142.

The changes in R2 in Models 2, 3 and 4 are in comparison to the value in Model 1. The changes in F-statistic are in comparison to the value in the previous model. The coefficients reported are unstandardized estimates, with standard errors in parentheses.

† p < 0.10.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

Hypothesis 3 is also supported. This finding is in line with the study of Smidts et al. (2001), who found that employees’ perception of the quality of information about their personal roles and about organizational issues is positively related to post-merger identification. Furthermore, it is consistent with the conclusion of Bartels et al. (2006) that positive perceptions of the quality of communication about the merger have a positive effect on identification with the post-merger organization.

Table 9.3 Results of regression analysis for testing Hypothesis 5

| Variables | Dependent variable = post-merger identification | Dependent variable = communication climate | R2 |

| Step 1: | |||

| Merger communication | 0.32** (0.10) | 0.17 | |

| Step 2: | |||

| Merger communication | 0.33** (0.07) | 0.20 | |

| Steps 3 and 4: | |||

| Merger communication | 0.25* (0.11) | 0.24 | |

| Communication climate | 0.35** (0.12) | ||

In order to analyse the mediating role of the communication climate (Hypothesis 4), the causal step approach of Baron and Kenny (1986) is followed. According to Baron and Kenny (1986), three conditions should be met to establish mediation – all are tested by means of regression analysis (see Table 9.3 for a summary of the results).

The first step is to assess the effect of merger communication on post-merger identification. A positive and significant effect for perceived quality and content of communication about the merger is observed (b = 0.32, p < 0.01). Then, the relation between the independent variable and the mediator is examined using regression analysis, with communication climate as the dependent variable. The same control variables as were used before are included in this analysis. We found that the perceived quality and content of communication about the merger is positively and significantly related to the perceived communication climate (b = 0.33, p < 0.01). The third and final step is to examine the effect of communication climate on post-merger identification, when the independent variable merger communication is controlled for. A positive and significant effect is found (b = 0.35, p < 0.01). Since all three steps are met and the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is less in the third (b = 0.25, p = 0.05) than in the first regression analysis, a partial mediation model can be established. Thus, it can be argued that the communication climate partly mediates the relationship between merger communication and employees’ identification with the post-merger organization. Furthermore, in addition to the approach of Baron and Kenny (1986), the mediation model is tested using Sobel’s test – a significance test for the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable via the mediator (Baron and Kenny, 1986). Since Sobel’s test statistic is significant (Sobel’s test statistic = 2.48, p < 0.05), we can support Hypothesis 4.

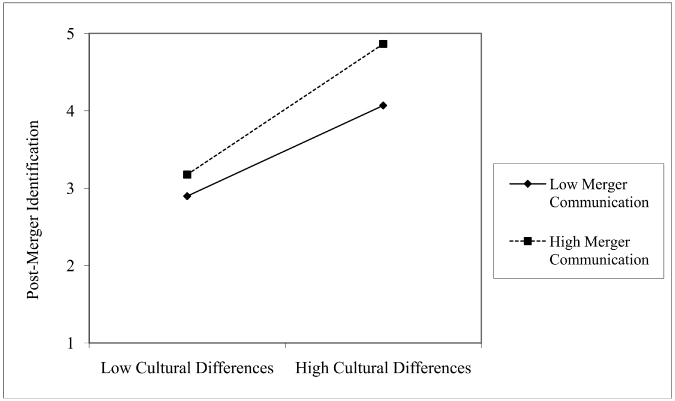

Figure 9.1 The relationship between cultural differences and post-merger identification moderated by merger communication

To test whether the cultural differences variable is differentially related to post-merger identification across employees with varying perceptions of merger communication (Hypothesis 5), we regressed post-merger identification on cultural differences, merger communication and cultural differences × merger communication. As can be seen from Model 4 in Table 9.2, the coefficient of the interaction term cultural differences × merger communication is significantly positive (b = 0.06, p < 0.01), thereby supporting Hypothesis 5. To gain further insight into the differences between employees with varying perceptions of merger communication, we plotted the relationship between cultural differences and post-merger identification for employees with low (i.e. ‘negative’) and high (i.e. ‘positive’) perceptions of merger communication (see Figure 9.1).

The regression lines represent the post-merger identification values expected on the basis of unstandardized regression coefficients from the complete regression analysis in Table 9.2 (Model 4).

Discussion

Theoretical and managerial implications

The results of this study reveal that employee communication during a post- merger integration process is an important determinant of the extent to which employees identify with the newly merged organization. Both employees’ positive perceptions of the content and quality of communication about the merger and the communication climate of the post-merger organization have positive effects on post-merger identification. Moreover, in our study a mediation effect is found of communication climate on the relationship between the perceived content and quality of communication about the merger and post-merger identification. Hence, better content and quality of communication about the merger improve the perceived communication climate in the post-merger organization and therefore the extent to which employees identify with the post-merger organization.

In the current study, the proposed relationship between perceived organizational cultural differences and post-merger identification is also found. This is consistent with the findings of Kroon et al. (2009), who concluded that perceived organizational cultural differences indirectly influence behavioural intentions, such as willingness to cooperate in the merger through the more explicit organizational identification process. Finally, we have observed an interesting interaction effect between merger communication and perceived cultural differences. That is, when organizational members feel that the content and quality of communication about the merger is correct and reliable, the relationship between cultural differences and post-merger identification is positively influenced.

Our study contributes to the literature on ‘human factors’ in post-merger integration. In previous literature it has been found that identification with the post-merger organization has a significant effect on post-merger integration outcomes, such as employee satisfaction, willingness to cooperate and turnover (intentions). In the current study, employee communication has a positive effect on post-merger identification, which implies that employee communication has an indirect effect on post-merger integration processes and M&A success.

Our study also contributes to social identity theory, which states that people derive part of their self-concept from the perceived membership in a relevant group or organization (Tajfel and Turner, 1986). The current study identifies additional antecedents of identification with the post-merger organization. Moreover, we clearly distinguish between identity and culture, two concepts which are often used interchangeably in the earlier literature. Finally, our findings illustrate how a mediation model and, in addition, a moderation model explain additional variance in our post-merger identification variable. These observations imply that multiple antecedents intricately interact to influence organizational identification in an M&A context. We therefore encourage further research to delve into the interactions of multiple determinants of organizational identification, including non-perceptual variables, such as changes in the leadership of the company.

Although communication problems are often seen as secondary concerns in post-M&A integration, they are apparent in most mergers and acquisitions (Vaara, 2003). Our study empirically shows how communication can influence employees’ perceptions of the M&A integration process. We also acknowledge the multi-dimensional nature of employee communication and distinguish between merger communication and communication climate of the merged organization. These two foci significantly influence post-merger identification but they also influence each other. From a managerial point of view, our findings imply that managers should invest in open and honest communication about the M&A and provide information about the goals and objectives, the developments and the consequences of the merger to employees in a timely manner. Information that is perceived by employees as reliable and relevant can improve the extent to which employees identify with the newly merged organization, which in turn can influence important attitudinal (e.g. satisfaction) and behavioural (e.g. turnover) variables in a post-merger integration process. Previous research has already illustrated that the development of a communication strategy is important in addressing organizational uncertainty. In addition, a poor communication programme may create significant problems and could even lead to the failure of the M&A (Clampitt et al., 2000; Papadakis, 2005).

Limitations and suggestions for future research

One important limitation of the current study is that the research was restricted to one particular post-M&A integration process. Single case studies place limitations on the generalizability of the results to other cases. Hence, there is no certainty that the findings are equally applicable to other research settings and contexts. However, we do feel that the findings can be used for ‘naturalistic generalization’, whereby one recognizes similarities between the findings of this research and those of other cases without making any statistical inference. We do encourage future research to examine other M&A settings and inter- and/or intra-organizational contexts in which radical organizational discontinuities occur.

A second limitation of our study is that we collected data at one point in time. Therefore, we have to be careful with a causal interpretation of the results. As previous studies have found support for the unstable and evolving nature of organizational identity, it would be interesting to examine changes in post-merger identification over time.

A final limitation concerns the nature of our data. We collected the independent and dependent variables using the same instrument. Hence, there is a risk of common method bias. However, Spector (2006) indicates that these method bias effects may be overstated. Moreover, support for Hypotheses 4 and 5 is unlikely to be an artefact of single respondent bias since it is implausible that respondents theorized such a mediated and moderated relationship when filling out the questionnaire. We also undertook procedural remedies against common method bias, such as protecting respondent anonymity and reducing item ambiguity.

In relation to our study’s findings, previous research has found that organizational identification is a relatively explicit and conscious process, whereas organizational culture is more tacit and implicit (Cartwright and Cooper, 1993; Hatch and Schultz, 2000; Ravasi and Schultz, 2006). Therefore, employee communication, which is often of an explicit nature, might influence post-merger identification and perceived cultural differences differently. Merger communication might also play a different role for indirectly involved employees than for those directly involved in the merger or acquisition. These issues, amongst others, might be interesting to address and explore in future research.

Appendix

Multi-item survey constructs

| Factor loadings (λ) | |

| Post-merger identification (Cronbach’s α = 0.87) | |

| 1. When someone criticizes (company A–B), it feels like a personal insult. | .71 |

| 2. I am very interested in what others think about (company A–B). | .70 |

| 3. When I talk about (company A–B), I usually say ‘we’ rather than ‘they’. | .76 |

| 4. When someone praises (company A–B), it feels like a personal compliment. | .87 |

| 5. (Company A–B)’s successes are my successes. | .76 |

| Merger communication (Cronbach’s α = 0.95) | |

| 1. I think the information I received about the merger was reliable. | .80 |

| 2. I think the information I received about the merger was true. | .80 |

| 3. Communication about the merger was open. | .81 |

| 4. I was sufficiently informed about the merger. | .77 |

| 5. I could easily get information about the merger. | .77 |

| 6. I received information about the merger on time. | .75 |

| 7. I think the information I received about the merger was useful. | .67 |

| 8. I am satisfied with the way I was informed about the latest developments of the merger. | .80 |

| 9. I am satisfied with the way I was informed about the objectives of the merger. | .72 |

| 10. I think the information I received about the merger was complete. | .76 |

| 11. I think the information I received about the merger was credible. | .73 |

| 12. Communication about the merger was honest. | .74 |

| 13. Openness and honesty about the merger were stimulated. | .65 |

| 14. I am satisfied with the communication about the merger at (company A–B). | .78 |

| Communication climate (Cronbach’s α = 0.85) | |

| 1. Generally speaking, everyone at (company A–B) is honest with one another. | .81 |

| 2. I can discuss anything with colleagues at (company A–B). | .66 |

| 3. Generally speaking, everyone at (company A–B) is open to one another. | .74 |

| 4. If I talk with colleagues at (company A–B), I feel I am being taken seriously. | .62 |

| 5. Colleagues at (company A–B) are open to the opinions of others. | .56 |

| 6. Colleagues at (company A–B) genuinely listen to me when I say something. | .59 |

| 7. My suggestions are taken seriously by my colleagues at (company A–B). | .64 |

| Integration impact (Cronbach’s α = 0.81) | |

| 1. My work has changed due to the merger. | .65 |

| 2. The structure has changed in the location I’m working at, due to the merger. | .77 |

| 3. Decision-making has changed in the location I’m working at, due to the merger. | .75 |

| 4. Systems and procedures have changed in the location I’m working at, due to the merger. | .70 |

| 5. Production technologies have changed in the location I’m working at, due to the merger. | .54 |

Note

1 Results for other construct combinations allow the same conclusion (i.e. discriminant validity is achieved).

References

Ager, D. L. (2011) ‘The emotional impact and behavioral consequences of post-M&Amp;A integration: An ethnographic case study in the software industry’, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 40: 199–230.

Aiken, L. S. and West, S. G. (1991) Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage.

Allatta, J. T. and Singh, H. (2011) ‘Evolving communication patterns in response to an acquisition event’, Strategic Management Journal, 32: 1099–1118.

Appelbaum, S. H., Gandell, J., Yortis, H., Proper, S. and Jobin, F. (2000) ‘Anatomy of a merger: Behavior of organizational factors and processes throughout the pre- during- post-stages (part 1)’, Management Decision, 38: 649–661.

Ashforth, B. E. and Mael, F. A. (1989) ‘Social identity and the organization’, Academy of Management Review, 14: 20–39.

Baron, R. M. and Kenny, D. A. (1986) ‘The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51: 1173–1182.

Bartels, J., Douwes, R., De Jong, M. and Pruyn, A. (2006) ‘Organizational identification during a merger: Determinants of employees’ expected identification with the new organization’, British Journal of Management, 17: S49–S67.

Bartels, J., Pruyn, A., De Jong, M. and Joustra, I. (2007) ‘Multiple organizational identification levels and the impact of perceived external prestige and communication climate’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28: 173–190.

Birkinshaw, J. M. (1999) ‘Acquiring intellect: Managing the integration of knowledge-intensive acquisitions’, Business Horizons, 42: 33–40.

Byrne, B. M. (2001) Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cartwright, S. and Cooper, C. L. (1993) ‘The role of culture compatibility in successful organizational marriage’, Academy of Management Executive, 7: 57–70.

Clampitt, P., DeKoch, R. and Cashman, T. (2000) ‘A strategy for communicating about uncertainty’, Academy of Management Executive, 14: 41–57.

Cording, M., Christmann, P. and King, D. R. (2008) ‘Reducing causal ambiguity in acquisition integration: Intermediate goals as mediators of integration decisions and acquisition performance’, Academy of Management Journal, 51: 744–767.

Corley, K. G. and Gioia, D. A. (2004) ‘Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 49: 173–208.

Costello, A. B. and Osborne, J. (2005) ‘Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis’, Practical Assessment Research and Evaluation, 10: 1–9.

DeNisi, A. S. and Shin, S. J. (2005) ‘Psychological communication interventions in mergers and acquisitions’. In G. K. Stahl and M. E. Mendenhall (eds), Mergers and acquisitions: Managing culture and human resources (pp. 228–236). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Diamantopoulos, A. and Siguaw, J. A. (2006) ‘Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration’, British Journal of Management, 17: 263–282.

DiGeorgio, R. (2002) ‘Making mergers and acquisitions work: What we know and don’t know – Part I’, Journal of Change Management, 3: 134–148.

Dyer, J. H., Kale, P. and Singh, H. (2004) ‘When to ally and when to acquire’, Harvard Business Review, 82: 108–115.

Epstein, M. J. (2004) ‘The drivers of success in post-merger integration’, Organizational Dynamics, 33: 174–189.

Epstein, M. J. (2005) ‘The determinants and evaluation of merger success’, Business Horizons, 48: 37–46.

Hatch, M. J. and Schultz, M. (1997) ‘Relations between organizational culture, identity and image’, European Journal of Marketing, 31: 356–365.

Hatch, M. J. and Schultz, M. (2000) ‘Scaling the tower of Babel: Relational differences between identity, image, and culture in organizations’. In M. Schultz, M.J. Hatch and M.H. Larsen (eds), The expressive organization (pp. 11–35). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hatch, M. J. and Schultz, M. (2002) ‘The dynamics of organizational identity’, Human Relations, 55: 989–1018.

Haunschild, P. R., Moreland, R. L. and Murrell, A. J. (1994) ‘Sources of resistance to mergers between groups’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24: 1150–1178.

Hildebrandt, L. (1987) ‘Consumer retail satisfaction in rural areas: A reanalysis of survey data’, Journal of Economic Psychology, 8: 19–42.

Hinkin, T. R. (1998) ‘A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires’, Organizational Research Methods, 1: 104–121.

Hogg, M. and Terry, D. J. (2000) ‘Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts’, Academy of Management Review, 25: 121–140.

Jimmieson, N. L., Terry, D. J. and Callan, V. J. (2004) ‘A longitudinal study of employee adaptation to organizational change: The role of change-related information and change-related self-efficacy’, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9: 11–27.

Kroon, D. P., Noorderhaven, N. G. and Leufkens, A. S. (2009) ‘Organizational identification and cultural differences: Explaining employee attitudes and behavioral intentions during postmerger integration’. In C. L. Cooper and S. Finkelstein (eds), Advances in mergers and acquisitions (pp. 19–42). Bingley: Emerald Group.

Larsson, R. and Lubatkin, M. (2001) ‘Achieving acculturation in mergers and acquisitions: An international case survey’, Human Relations, 54: 1573–1607.

Mael, F. A. and Ashforth, B. E. (1992) ‘Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification’, Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 13: 103–123.

March, J. G. and Simon, H. A. (1958) Organizations. New York: Wiley.

Makri, M., Hitt, M. A. and Lane, P. J. (2010) ‘Complementary technologies, knowledge relatedness, and invention outcomes in high technology mergers and acquisitions’, Strategic Management Journal, 31: 602–628.

Papadakis, V. M. (2005) ‘The role of broader context and the communication program in merger and acquisition implementation success’, Management Decision, 43: 236–255.

Ravasi, D. and Schultz, M. (2006) ‘Responding to organizational identity threats: Exploring the role of organizational culture’, Academy of Management Journal, 49: 433–458.

Schweiger, D. M. and DeNisi, A. S. (1991) ‘Communication with employees following a merger: A longitudinal field experiment’, Academy of Management Journal, 34: 110–135.

Scott, C. R. (1997) ‘Identification with multiple targets in a geographically dispersed organization’, Management Communication Quarterly, 10: 491–522.

Seo, M. and Hill, N. S. (2005) ‘Understanding the human side of mergers and acquisitions: An integrative framework’, Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41: 422–443.

Shrivastava, P. (1986) ‘Postmerger integration’, Journal of Business Strategy, 7: 65–76.

Smidts, A., Pruyn, A. T. H. and Van Riel, C. B. M. (2001) ‘The impact of employee communication and perceived external prestige on organizational identification’, Academy of Management Journal, 44: 1051–1062.

Sonenshein, S. (2010) ‘We’re changing or are we? Untangling the role of progressive, regressive and stability narratives during strategic change implementation’, Academy of Management Journal, 53: 477–512.

Spector, P. E. (2006) ‘Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend?’, Organizational Research Methods, 9: 221–232.

Tajfel, H. and Turner, J. C. (1986) ‘The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour’. In S. Worchel and W. G. Austin (eds), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall.

Teerikangas, S. (2007) ‘A comparative overview of the impact of cultural diversity on inter-organizational encounters’. In C. L. Cooper and S. Finkelstein (eds), Advances in mergers and acquisitions (pp. 37–76). Amsterdam: JAI Press.

Terry, D. J. and Callan, V. J. (1998) ‘In-group bias in response to an organizational merger’, Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice, 2: 67–81.

Terry, D. J., Carey, C. J. and Callan, V. J. (2001) ‘Employee adjustment to an organizational merger: An intergroup perspective’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27: 267–280.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D. and Wetherell, M. (1987) Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Ullrich, J. and Van Dick, R. (2007) ‘The group psychology of mergers and acquisitions: Lessons from the social identity approach’. In C. L. Cooper and S. Finkelstein (eds), Advances in mergers and acquisitions (pp. 1–15). Amsterdam: JAI Press.

Vaara, E. (1999) ‘Cultural differences in post-merger problems: Misconceptions and cognitive simplifications’, Nordic Organization Studies, 1: 59–88.

Vaara, E. (2003) ‘Post-acquisition integration as sensemaking: Glimpses of ambiguity, confusion, hypocrisy, and politicization’, Journal of Management Studies, 40: 859–894.

Van Dick, R., Ullrich, J. and Tissington, P. A. (2006) ‘Working under a black cloud: How to sustain organizational identification after a merger’, British Journal of Management, 17: S69–S79.

Van Knippenberg, D., Van Knippenberg, B., Monden, L. and De Lima, F. (2002) ‘Organizational identification after a merger: A social identity perspective’, British Journal of Social Psychology, 41: 233–252.

Zaheer, S., Schomaker, M. and Genc, M. (2003) ‘Identity versus culture in mergers of equals’, European Management Journal, 21: 185–191.