PROGRAM FORMATS

“The devil is in the details,” wrote famed French author Gustave Flaubert, and for our purposes in this chapter, we could say that the devil is in the programming. Alternately, we could opt for the observation of revered U.S. Navy Admiral Hyman Rickover, who concluded that “The Devil is in the details, but so is salvation.” Indeed, designing a radio station’s sound continues to be a bedeviling yet emancipating task, its intensity amplified in an environment complicated by station ownership consolidation and the resultant clustering of stations within markets. More than 15,500 AM and FM stations compete for audience attention, and additional broadcasters continue to enter the fray. Other media have emerged and proliferated to further distract and dilute radio’s customary audience. The government’s laissez-faire, “let the marketplace dictate” philosophy concerning commercial radio programming gives the station great freedom in deciding the nature of its air product. Yet determining what to offer the listener, who is often presented with dozens of audio alternatives, involves intricate planning. Consultant and Programmer Mike McVay of Cumulus Media underscores the role good programming plays in achieving station success:

Radio stations are simply a platform for distribution. The content of a radio station is what makes it a success or a failure. Great programming is targeted to the largest possible audience, designed based on research that enables one to know what needs should be satisfied, easy to understand and memorable. If you are to succeed with a product, particularly in an era when mass media still dominates niche media, the most popular widespread formats (talk or music) should be what is presented. Bigger is better. It enables you to overcome rating wobbles. Without good programming you have nothing,

Tommy Castor, PD of iHeartmedia’s Channel963 in Wichita, sums it up this way:

I strongly believe that good programming on radio, in many cases, can be the ultimate deciding factor between consumers using radio and using a curated or on-demand service. While curated and on-demand services and radio share a similarity in that the consumer doesn’t usually have ultimate control of the selection of the music, radio programming differs because rather than guessing what the consumer might like to listen to (based on an artist or song selection on the curated service), radio program directors use a variety or research, metrics and strategies to put together a playlist of music.

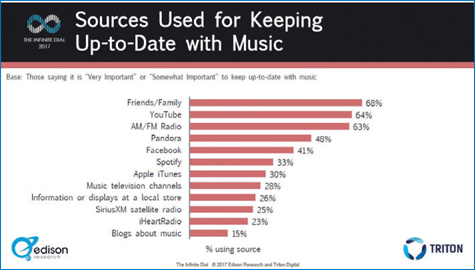

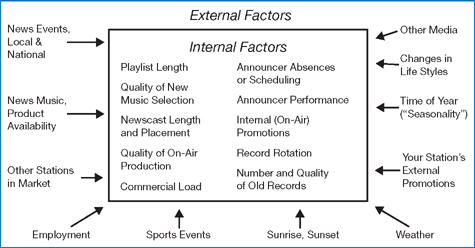

The bottom line, of course, is to air the type of format that will attract a sizable enough piece of the audience demographic to satisfy the advertiser. Once a station decides on the format it will program, it must then know how to effectively execute it. Since 1998 Edison Research has reported on radio audience demographics in its annual Infinite Dial studies. In its most recent study of 2,000 participants, Edison and research partner Triton Digital affirm the diversification within traditional radio and online audio services. Podcast listening continues to make double-digit percentage advancements. As a result of recent gains researchers say the platform as of 2017 qualifies for “mainstream media” status. They estimate 112 million listeners have sampled podcasts. The report reveals that 45% of respondents listen to “most of the podcast,” while another 40% hear the podcast in its entirety. Terrestrial (AM and FM) stations, according to the research, remain the most popular audio medium across all respondent ages for the discovery of new music (but rank third for 12- to 24-year-old listeners, behind YouTube and “friends and family”). In the so-called “battle for the dashboard,” AM and FM stations dominate, outdistancing the runner-up (CD listening) by 30 percentage points. Pandora awareness and listenership remains high. Yet, despite the inroads the pureplay has made in selling advertising in individual markets, it hasn’t yet achieved granularity in terms of providing local information and entertainment— the content that attracts an audience. Thus, if “location, location, and location” are the three keys to success in selling real estate then “local, local, and local” emerges as the guiding principle for programmers at FM and AM stations to follow in creating the types of compelling radio programming that pureplays have yet offered.

Brief descriptions of several of radio’s most widely adopted music formats today are presented in this chapter (for a discussion of nonmusic program formats, see Chapter 5). There are, however, more than 60 distinct music and nonmusic formats recognized by the audience research firm Nielsen Audio. The reader should keep in mind that formats morph and evolve as new trends in lifestyle and culture emerge.

Changes in audience measurement methodologies can influence programming decisions, as well as the outcomes of the research. Inside Radio, an industry newsletter, reported a correlation between format changes and the markets in which Nielsen Audio had implemented its Portable People Meter (PPM) system. Chapter 6 details PPM history and explains how Nielsen Audio continues its transition from a diary-based, listener-recall data collection method to an electronic, passive system for audience measurement. Most importantly, it bears observing that radio formats are dynamic and malleable, and the impetus for change is driven by various, largely economic factors.

Adult Contemporary

In terms of the number of listeners, adult contemporary (AC, and offsprings hot AC, lite AC, modern AC, rhythmic AC, soft AC, and urban AC) continues its four-decade popularity trend. The core AC format, according to Inside Radio, is programmed on approximately 600 stations. When the various subformats are included in the count, the total station count springs to more than 1,400 outlets. It’s radio’s second most listened-to music format, trailing only contemporary hit radio (CHR). A notable characteristic of AC is its widespread appeal to women. The format attracts radio’s most evenly distributed audience of listeners aged 12 to 64. AC is ethnically diverse, targeting female listeners aged 25–54 and focusing on a core of females between 30 and 45 years old. AC popularity is trending upward with teens and young adults. Almost one-third of listeners are college-educated. This programming approach is prone to fragmentation, a phenomenon ascribed to the notable population diversity across the subgroups of the core format.

Because AC is very strong among the broader 25–54 age group it is particularly appealing to advertisers. Two core audience characteristics—above-average disposable income and the responsibility for managing day-to-day household spending—make this group a desirable advertiser target. Also, some advertisers spend money on AC stations simply because they like the format themselves. In sum, the AC format is one of the most effective in attracting female listeners.

AC outlets emphasize current and not-so-current (all the way back to the 1970s at some AC stations) pop standards, sans raucous or harsh beats. In other words, there’s no hard rock, although some AC stations could be described as soft rockers. Nonetheless, the majority of stations mix in enough ballads and easy listening sounds to justify their title. The main thrust of this format’s programming is the music. Programming consultant Alan Burns has studied the relationship between females and radio listening. One of the more telling pieces of information to appear in his study Here She Comes—Insights Into Women, Radio, and New Media underscores the importance of music to adult females. Data revealed that, for two of every three listeners surveyed, music is the primary reason for tuning in. Despite the popularity and perceived importance of the morning show to a station’s success, only one in four survey respondents cited it as the principal reason for listening. More music can be aired whenever the chatter is deemphasized. Songs are commonly presented in uninterrupted sweeps or blocks, perhaps 10–12 minutes in duration, followed by a brief recap of artists and titles. Despite the importance of music to the success of the format high-profile morning talent or teams remains a contributor to station popularity at certain AC stations. Commercials generally are clustered at predetermined times, and midday and evening deejay talk is minimal and is often limited to brief informational announcements. News and sports are secondary to the music. In recent years, ACs have spawned a host of format permutations, such as adult hits and adult standards. In the late 2000s, according to Arbitron, the AC subgenre showing the most growth was urban AC.

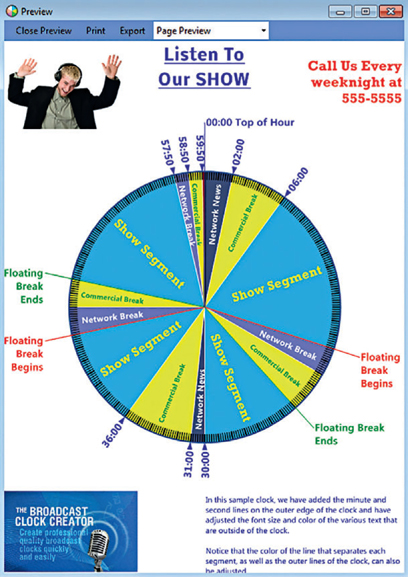

FIGURE 3.1

America’s top formats, ranked by share of total listening

Source: Courtesy of Nielsen Audio

Adult Hits/Classic Hits

Programmers seized the opportunity to meld aspects of traditional classic hits, pop, and alternative radio formats, widening the depth of the playlist to create what is popularly known as the adult hits or classic hits format. An esoteric format derivative, known variously as “Jack,” “Bob,” “Dave,” and other names, predominantly of the male gender, evolved as one of the more successful programming approach variants. “Jack” and its masculine siblings represent attempts at humanizing a radio station, imbuing it with personality in efforts to evoke and grow listener affinity. Influenced by user experience with the iPod, and its ability to shuffle the playback of users’ massive song collections in creating a randomized playback sequence, “Jack,” “Bob,” and “Dave” programmers thumbed their noses at radio’s tightly controlled playlist approach, on occasion venturing as far back as the 1960s for music selections.

By tapping into the mindset of listeners who had grown tired of the predictability and repetition of the music presentation, “Jack” outlets have proven to be particularly successful in attracting the attention of males and females aged 35 to 44. A commonly heard positioning catchphrase, expressed in slightly different versions by stations in their on-air imaging (i.e., the airing of creative audio elements that establish and promote station personality), alludes to this approach. Buffalo’s 92.9 “Jack FM,” Baltimore’s 102.7 “Jack fm,” and Sacramento’s 93.7 “Jack fm,” among others, proclaim that music variety is achieved by “Playing what we want.” In Nashville, 96.3 “Jack fm” asserts: “We play what we want.” Despite variations in the phrasing, the approach remains the same. Classic hits popularity waned in the early 2000s but, according to industry observer and columnist Sean Ross, the format is resilient and relevant.

FIGURE 3.2

In the mid-2000s, radio programmers conceived a format for emulating the diversity of song choices available on an iPod

Source: Courtesy of Jack FM 105.9

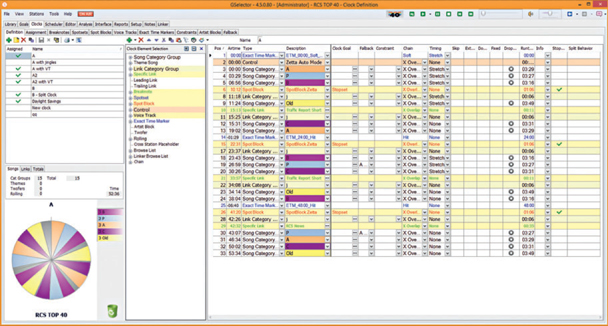

Contemporary Hit Radio

Contemporary hit radio (CHR) is the format successor to the Top 40 stations popularized during rock ‘n’ roll’s infancy in the 1950s. Stations play only those recordings that are currently the fastest selling and most active on social media. CHR’s narrow playlists are designed to draw teens and young adults. The heart of this format’s demographic is 12- to 18-year-olds, although by the mid-1980s it had broadened its core audience. CHR is subject to fragmentation, the result of programmers’ efforts to attract specific demographic targets. The core format takes a mainstream approach to music, focusing primarily on pop and dance tunes. Rhythmic CHR embraces R&B and hip-hop, while adult CHR’s library draws from current and older chart classics.

Like AC, it too has experienced fluctuations in popularity over the decades. The broad swath of musical styles prevalent in the ‘90s divided listener interests and loyalties. The outcome? A number of stations abandoned the format. At one point only a couple of hundred CHR stations remained. The 1990s was a particularly troublesome decade in this regard: the sale of tangible music products (45-rpm records, cassette and CD singles) was fading and downloadable digital song files had yet to materialize. Over time, interest in the format revived and by 2010 the format resurged in popularity following the expanded implementation of Arbitron’s (now Nielsen Audio’s) Portable People Meter (PPM) measurement.

The format is characterized by its swift and often unrelenting pace. Silence, known as “dead air,” is the enemy. The idea is to keep the sound hot and tight to keep the kids from station hopping, which is no small task in markets where two or more hit-oriented stations compete for listeners. CHR deejays have undergone several shifts in status since the inception of the chart music format in the 1950s. Initially, pop deejay personalities played an integral role in the air sound. However, in the mid-1960s, the format underwent a major change when deejay presence was significantly minimized. Programmer Bill Drake renovated the top 40 sound, tightening the deejay talk and the number of commercials in order to improve the song flow. Despite criticism that the new sound was too mechanical, Drake’s technique succeeded at strengthening the format’s hold on the listening audience.

In the middle and late 1970s, the deejay’s role on hit stations began to regain its former prominence. The format underwent further renovation in the 1980s (initiated by legendary consultant Mike Joseph) that resulted in a narrowing of the playlist and a decrease in deejay presence. Super or hot hit (synonymous terms for the format) stations were among the most popular in the country and could be found either near or at the top of the rating charts in their markets.

Mainstream CHR has trended toward a less frenetic, more mature sound. In undergoing an image adjustment, programmers are keying in on improving overall flow of format elements. The continued preening of the playlist and the inclusion of what analyst Sean Ross terms “adult-friendly” music will keep the format viable, say the experts. In the top 40 ‘60s and ‘70s many stations enlarged listenership by connecting not only to a primary audience of teens but secondary audiences of parents who tuned in out of curiosity about their children’s musical tastes as well as adults who used radio as a means of reclaiming and preserving the feelings of their youth.

| STATION FORMAT COUNT, MAY 2016 | |

| Format | Stations |

| Active rock | 165 |

| Adult contemporary | 587 |

| Adult hits | 167 |

| Adult standards/middle of the road | 129 |

| Album adult alternative | 154 |

| Album-oriented rock | 66 |

| All-news | 21 |

| All-sports | 582 |

| Alternative | 163 |

| Christian adult contemporary | 52 |

| Classic country | 281 |

| Classical | 204 |

| Comedy | 7 |

| Country | 1882 |

| Easy listening | 22 |

| Educational | 52 |

| Gospel | 296 |

| Hot adult contemporary | 469 |

| Jazz | 60 |

| Mainstream rock | 73 |

| Modern adult contemporary | 16 |

| New country | 128 |

| News/talk/information | 1,315 |

| Nostalgia | 23 |

| Oldies | 365 |

| Other | 36 |

| Pop contemporary hit radio | 464 |

| Religious | 722 |

| Rhythmic | 192 |

| Smooth adult contemporary | 5 |

| Soft adult contemporary | 75 |

| Southern gospel | 116 |

| Spanish | 371 |

| Talk/personality | 131 |

| Urban adult contemporary | 162 |

| Urban contemporary | 144 |

| Urban oldies | 29 |

| Variety | 409 |

| World ethnic | 46 |

FIGURE 3.3

Format counts, as reported by Nielsen Audio

Source: Courtesy of Nielsen Audio

News is of secondary importance on CHR stations. In fact, many program directors (PDs) consider news programming to be a tune-out factor. “Kids don’t like news,” they claim. However, despite the industry deregulation that eased the requirements for broadcasting nonentertainment programming, most retain at least a modicum of news out of a sense of obligation. CHR stations remain very promotion-minded and contest-oriented.

Multiyear growth patterns in ratings and share of audience are notable. In its most recently published findings, Nielsen Audio identifies pop (mainstream) CHR as the top format for radio listeners aged six years and older—a feat the format has achieved for three years running. Slightly more than 600 stations (nearly all of them are FM) call themselves CHR, according to the industry newsletter Inside Radio. Many of these stations prefer the labels mainstream CHR or pop CHR. Format variants include rhythmic CHR, dance CHR, and adult CHR.

Country

The country format has been adopted by more stations than any other and has become one of the leaders in the ratings race. Its appeal is exceptionally broad. An indication of country music’s popularity is the fact that there many more full-time country stations today than in its nascent years. The estimated station count now totals more than 2,100 country, new country, and classic country AM and FM broadcasters. This format is far more prevalent in the South and Midwest, and it is not uncommon for stations in certain markets to enjoy double-digit ratings successes. Although most medium and large markets have country stations, country in the top five major markets appears on the lists of the top 10-rated stations in just two cities, Chicago and Dallas/Ft. Worth. Owing to the diversity of approaches within the format—for example, classic, Cajun, bluegrass, traditional, and so on—the country format attracts a broad age group, appealing to young and old adults alike. Listening percentages peak with persons between 45 and 54 and the demographic skews slightly to females. Fans of the format are more likely to listen to the radio at work than are listeners to other formats.

Two related and encouraging trends for proponents of the format involve younger listeners. The derivative “new country” offshoot format continues to pull in strong ratings numbers, helping to propel the genre to the second-highest rated format nationally for teens. No doubt in response to immensely popular younger artists such as Maren Morris and Kelsea Ballerini, stations are capitalizing on the promotional opportunities that young artists present, staging what former Country Radio Broadcasters president Paul Allen termed “‘high school spirit’-type contests to target the next generation of listeners.”

Country radio has always been particularly popular among blue-collar workers. However, the Country Music Association and the Organization of Country Radio Broadcasters report that the country music format is drawing a more upscale, better-educated audience today than it did in the past. In the 2010s, as many FM as AM stations are programming the country sound, which was not the case just a few years before. Until the 1980s, country was predominantly an AM offering. Depending on the approach they employ, country outlets may emphasize or deemphasize air personalities, include news and public affairs features, or confine their programming almost exclusively to music.

Some programming experts point to the mid-1990s as the greatest period for the country format, but its long-term history reflects periods of growth and retrenchment dating to the 1950s. The format’s seesaw popularity swung from #1 in the years 2011 and 2015 but slipped to the fourth position in 2016, a downward turn possibly resulting from the resurgent popularity of the news/talk format in the hotly contested 2016 election year. Another characteristic of the format that has risen and waned over the years is its reliance on “crossovers”—songs recorded by artists who appeal to two different audiences. The practice of playing crossover hits from the Top40/CHR format is once again in programming vogue at country stations due in part to the universal appeal and popularity of acoustic pop artists.

Soft Adult/Easy Listening/Smooth Jazz

Instrumentals and soft vocals of established songs are a mainstay at soft adult/easy listening stations, which also share a penchant for lush orchestrations featuring plenty of string orchestrations. Talk is deemphasized, and news presentation is limited to morning drive time. These stations boast a devoted audience of typically older listeners.

Efforts to draw younger persons into the easy listening fold have been moderately successful, but most of the format’s primary adherents are over 50 years old. Music syndicators provide satellite-delivered, preproduced programming to approximately half of the nation’s easy listening/soft adult stations. Easy listening lost some ground in the 1990s and 2000s to AC and other adult-appeal formats such as album adult alternative and new age. A more recent format variant, smooth jazz, fuses the sounds of jazz, pop, rock, and other music genres in a low-key presentation that features minimal announcer presence and interruption. Following a decade of popularity, the format declined in the mid-2000s. One reason for this, it appears, is that its core audience purchased few artist CDs or downloads. Devoted listeners were satisfied instead by whatever selections their stations offered and weren’t especially interested in product ownership.

Soft adult, lite and easy, smooth jazz, adult standards, and urban AC have become replacement nomenclatures for easy listening, which, like the related moniker Beautiful Music, also began to assume a geriatric connotation.

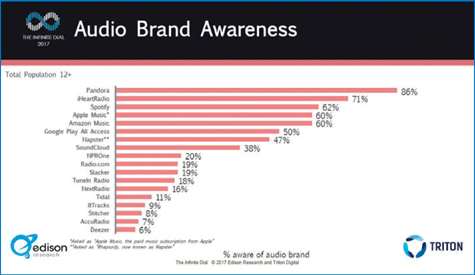

FIGURE 3.4

Audio Brand Awareness. From The Infinite Dial 2017 study

Source: Courtesy of Edison Research and Triton Digital

Classic, Active, Modern, and Alternative Rock

The birth of the album-oriented rock (AOR) format in the late 1960s (also called underground and progressive) was the result of a basic disdain by certain listeners for the highly formulaic top 40 sound that prevailed at the time. In the summer of 1966, WOR-FM, New York, introduced progressive radio, the forerunner of AOR. As an alternative to the super-hyped, ultra-commercial sound of hit song stations, WOR-FM programmed an unorthodox combination of nonchart rock, blues, folk, and jazz. In the 1970s, the format concentrated its attention almost exclusively on album rock, while becoming less freeform and more formulaic and systematic in its programming approach.

Today, AOR is often simply called rock, or more specifically modern rock or classic rock. Although it continues to do well in garnering the 18- to 34-year-old male demographic, this format has always done poorly in winning female listeners, especially when it emphasizes a heavy or hard rock playlist. This has proven to be a sore spot with certain advertisers. In the 1980s, the format lost its prominence owing, in part, to the meteoric rebirth of hit radio. However, as the decade came to an end, AOR had regained a chunk of its numbers, and in the 1990s it renamed itself modern rock. Active rock stations now adhere more faithfully to the AOR approach; as analyst Sean Ross noted, the two formats progressed lockstep in the 2000s until modern rock diverged and proponents advocated its distinction from the alt-rock enthusiasts. Ross observed in mid-2016 that both formats are enjoying a healthy existence and their outlook for success is positive. In combination they accounted for slightly more than 10% of the radio audience that year.

Generally, rock stations broadcast their music in sweeps, segueing at least two or three songs. A large song library is typical, in which 300–700 cuts may be active. Depending on the outlet, the deejay may or may not have “personality” status. In fact, the more music/less talk approach particularly common at easy listening stations is emulated by many album rockers. Consequently, news plays a very minor part in the station’s programming efforts. Active rock stations are very lifestyle-oriented and invest great time and energy developing promotions relevant to the interests and attitudes of their listeners. The alternative rock format tries for distinctiveness in contrast to the other rock radio approaches. Creating this alternative sound is a challenge, says Stephanie Hindley, PD of Buzz 99.9:

The Alternative format is a great challenge for programmers. Think of the music you liked and the things you did when you were 18. Now think of the music you liked (or will like) and the things you did (or will do) at age 34. Despite the vast differences in taste in the 18–34 demographic, we need to play music that will appeal to as many people as possible within this diverse group.

In comparison with other rock variants, alternative listeners typically are better educated (two out of three have attended a university or have earned a degree). Additionally, the format attracts the highest percentage of Hispanic and black listeners within the “rock” family of formats. As Hindley explains,

It’s a constant balancing act. We have to play a lot of new music without sounding too unfamiliar. We have to be cool and hip without sounding exclusive. We have to be edgy without being offensive. Be smart without sounding condescending. Young and upbeat without sounding immature. As long as those balances are maintained on a daily basis, we will continue to have success in this format.

Classic/Oldies/Nostalgia

These three related formats are differentiated by song choices that all enjoyed popularity decades ago. A decade ago the nostalgia station was characterized by a playlist organized around tunes popular as far back as the 1940s and 1950s, while the oldies outlet directed its focus on playing the pop hits of the late 1950s and 1960s. Today, nostalgia-formatted stations typically define their target decades as the ‘50s and ‘60s, while the oldies outlets are more attuned to the music of the 1970s and 1980s. A typical oldies quarter-hour might consist of songs by Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Fleetwood Mac, Elton John, and the Ronettes. In contrast, a nostalgia quarter-hour might consist of tunes from the pre-rock era, performed by adult-appeal artists such as Frankie Laine, Les Baxter, the Mills Brothers, Tommy Dorsey, and popular ballad singers of the mid-1900s.

“Music of your life” (MOYL), a vocal-intensive, 24-hour nostalgia presentation created in the 1970s by pop music composer and performer Al Ham, continues to be heard nationwide on a network of approximately 50 stations, freshening its playlist to include softer pop hits of the 1960s and 1970s. Stations airing nostalgia programming more likely acquire it from syndicators such as MOYL rather than attempting to program it in-house. Because much of the music predates stereo recording techniques, AM outlets are most apt to carry the nostalgia sound. Music is invariably presented in sweeps, and, for the most part, deejays maintain a low profile.

The oldies format was first introduced in the 1960s by programmers Bill Drake and Chuck Blore. Although nostalgia’s audience tends to be over the age of 60, the audience for oldies skews somewhat younger. One-third of oldies listeners grew up in the turbulent, rebellious 1960s and, unsurprisingly, the music of this decade constitutes the core of the song library. Unlike nostalgia, most oldies outlets originate their own programming. In contrast with its vintage-music cousin, the oldies format features greater deejay presence. Music is rarely broadcast in sweeps, and commercials, rather than being clustered, are inserted in a random fashion between songs.

The format descriptor “oldies” is being abandoned in favor of the label “classic hits.” More pop- than rock-oriented, this 1960s- to1980s-focused format has exhibited constant ratings growth in the 2000s on more than 500 outlets. Classic hits stations are favored almost equally by male and female listeners, and particularly those aged 45 to 64. Classic rock emphasizes the music of the iconic rock artists and attracts a predominantly (70%) male audience. By concentrating on tunes essentially featured by former AOR stations over the past three decades, the harder-edged classic rock format contrasts with the classic hits formula, which fills the gap between oldies and CHR outlets with playlists that draw from 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s top 40 charts.

Urban Contemporary

Considered the “melting pot” format, urban contemporary (UC) attracts more than 31 million African-American listeners each week, a statistic that Nielsen Audio says translates to 92% of the AA population— with a near-equal mix of males and females—that radio reaches each week. Hispanic listeners, who constitute the largest minority in the nation, and whites are also in the mix; together they account for one in five audience members. As the term suggests, stations employing this format are usually located in metropolitan areas with large, heterogeneous populations. Interestingly, however, the format currently exhibits higher than national average audience shares across the deep South, which include several urban markets (although Atlanta is the only one that is considered to be a “major market”). A descendant of the heritage black program format, UC was born in the early 1980s, the offspring of the short-lived disco format, which burst onto the scene in 1978. At its inception, the disco craze brought new listeners to the black stations, which shortly saw their fortunes change when all-disco stations began to surface. Many black outlets witnessed an exodus of their younger listeners to the disco stations. This prompted a number of black stations to abandon their more traditional playlists, which consisted of rhythm and blues, gospel, and soul tunes, for exclusively disco music. When disco perished in the early 1980s, the UC format emerged. Today, progressive black stations, such as WBLS-FM, New York, combine dance music with soulful rock and contemporary jazz, and many have transcended the color barrier by including certain white artists on their playlists. In fact, many black stations employ white air personnel in efforts to broaden their demographic base.

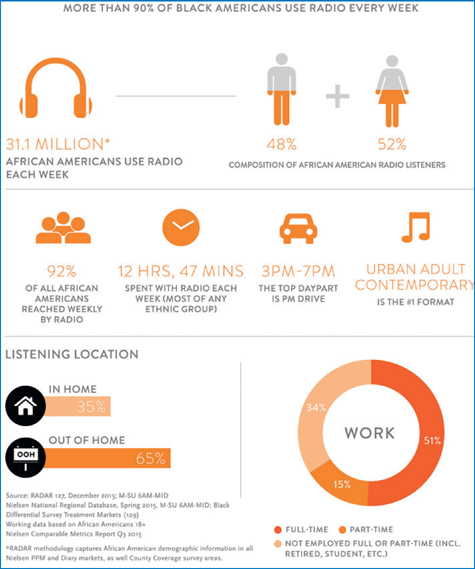

FIGURE 3.5

More than 80% of black Americans use radio each week

Source: Courtesy of Nielsen Audio

UC is characterized by its upbeat, danceable sound and deejays that are hip, friendly, and energetic. Stations stress danceable tunes and their playlists generally are anything but narrow. However, a particular sound may be given preference over another, depending on the demographic composition of the population in the area that the station serves. For example, UC outlets may play greater amounts of music with a Latin or rhythm and blues flavor, whereas others may air larger proportions of light jazz, reggae, new rock, or hip-hop. Some AM stations around the country have adopted the UC format; however, it is more likely to be found on the FM side, where it has taken numerous stations to the forefront of their market’s ratings.

The UC influence on the formats of traditional black stations is evidenced by the swell in popularity of the urban adult contemporary (urban AC) variant and in the age alignment of audiences for the two formats. Urban AC listeners are predominantly middle-aged (35–54) African Americans who tend to stay tuned to stations for longer periods than do similarly aged listeners to other formats. This information correlates with the finding that in 2016 urban AC was the top-rated format among blacks aged 12+. UC has had an impact on urban AC stations, which have experienced erosion in their youth numbers. More than a third of listeners to the nation’s 270 UC stations are aged 23 and younger and a substantial amount of listening occurs in the after-school hours. Many UC stations have countered by broadening their playlists to include artists who have not traditionally been programmed. Because of the format’s high-intensity, fast-paced presentation, UC outlets can give a Top 40 impression. In contrast, they commonly segue songs or present music in sweeps and give airplay to lengthy cuts that are sometimes six to eight minutes long. Although top 40 or CHR stations seldom program cuts lasting more than four minutes, UC outlets find long cuts or remixes compatible with their programming approach. Remember, UCs are very dance-oriented. Newscasts play a minor role in this format, which caters to a target audience aged 18–34. Contests and promotions are important program elements.

A portion of urban outlets have drawn from the more mainstream CHR playlist in an attempt to expand their listener base. Several large-market stations transitioned from rhythmic CHR to hip-hop since the previous edition of this book was published. Further evidence of format splintering can be found in the recent emergence of classic hip-hop, a descriptor that consultant Harry Lyles suggests could be more fittingly termed “Old School Hip Hop.” Programmer Mike McVay notes a trend that classic hip-hop stations start strong but begin to experience ratings erosion a year or so later. Meanwhile, the old-line, heritage R&B and gospel stations still exist and can be found mostly on AM stations in the South.

Classical

Approximately 200 stations—the overwhelming majority of which are licensed as noncommercial outlets—program classical music. For the few remaining commercial stations, a loyal audience following enables owners to generate a modest to good income. Over the years, profits have remained relatively minute in comparison to other formats. However, member stations of the Concert Music Broad casters Association reported ad revenue increases of up to 40% in the 1980s and 1990s with continued growth, albeit modest, in the 2000s. Owing to its upscale audience, blue-chip accounts find the format an effective buy. This is first and foremost an FM format insofar as the nature of the program content necessitates delivery via a high-fidelity medium.

In many markets, the performance of commercial classical stations has been affected by public radio outlets that program classical music. Because commercial classical stations must break to air the sponsor messages that keep them operating, they must adjust their playlists accordingly. This may mean shorter cuts of music during particular dayparts—in other words, less music. The noncommercial classical outlet is relatively free of such constraints and thus benefits as a result. A case in point is WCRB-FM in Boston, the city’s only full-time classical station. Although it was attracting most of the area’s classical listeners throughout the afternoon and evening hours, it lost many patrons to public radio WGBH’s classical segments with fewer programming interruptions. In 2010 WGBH purchased WCRB-FM, relegating its classical music programming to the former commercially operated station and repositioning its programming approach to news and information.

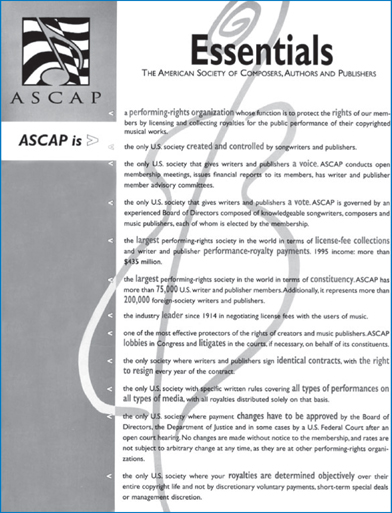

FIGURE 3.6

Radio stations pay an annual fee to music licensing services such as ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC

Source: Courtesy of ASCAP

Classical stations target the 25- to 49-year-old, higher-income, college-educated listener. News is typically presented at 60- to 90-minute intervals and generally runs from five to 10 minutes. The format is characterized by a conservative, straightforward air sound. Sensationalism and hype are avoided, and on-air contests and promotions are as rare as announcer chatter.

Religious/Christian

Live broadcasts of religious programs began while the medium was still in its experimental stage. In 1919, the U.S. Army Signal Corps aired a service from a chapel in Washington, D.C. Not long after that, KFSG in Los Angeles and WMBI in Chicago began to devote themselves to religious programming. Soon dozens of other radio outlets were broadcasting the message of God.

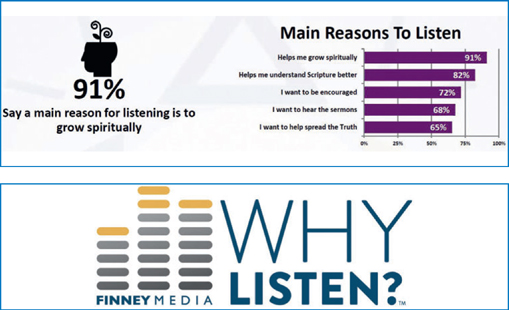

FIGURES 3.7A AND 3.7B

The executive summary for Christian radio stations airing both music and several hours of talk programs comes from data collected in Spring 2016, part of the Finney Media Why Listen national survey of Christian radio station listeners in the U.S. and Canada. Additional detail at finneymedia.com under the WHY LISTEN tab

Source: Courtesy of Finney Media

Religious broadcasters typically follow one of two programming approaches. One includes music as part of its presentation, and the other does not. Contemporary Christian-formatted stations feature music oriented toward a Christian or life-affirming perspective. Nielsen Audio estimated in 2016 that almost 900 stations representing all geographic areas attracted listeners across a wide range of ages. The typical listener is almost twice as likely to be female than male and of above-average education. Finney Media, a program consultancy specializing in service to Christian-formatted stations, says listeners to the format have two clear expectations. According to results of its 2016 Why Listen? survey, “77% come to Christian radio to be encouraged” and “a full 79% said that a main reason they listen is for worshipful Christian music.”

A notable presence to emerge in recent years is K-Love, the contemporary Christian music service that operates a nationwide network of 400-plus FM full-power and translator stations. Operated by the California-based nonprofit Educational Media Foundation, K-Love offers a music-focused presentation with minimal interruption.

What innovation could propel the format to its next level? Consultant and talent coach Tracy Johnson told Inside Radio:

Well-programmed contemporary Christian stations have the most loyal fan base I’ve ever seen. With the right moves, the format could greatly expand its appeal beyond the religious base, especially in a society where consumers are so stressed. How about adding more reasons to listen, like highprofile air talent?

Faith-affirming gospel stations feature music that has its origins in the black church; Southern gospel-formatted stations are mainstays of the South and Midwest; their music appeals to white listeners. Gospel programming can be heard mostly on AM stations. In all instances, music-intensive stations include the scheduling of blocks of religious features and programs. Nonmusic religious outlets concentrate on inspirational features and complementary talk and informational shows.

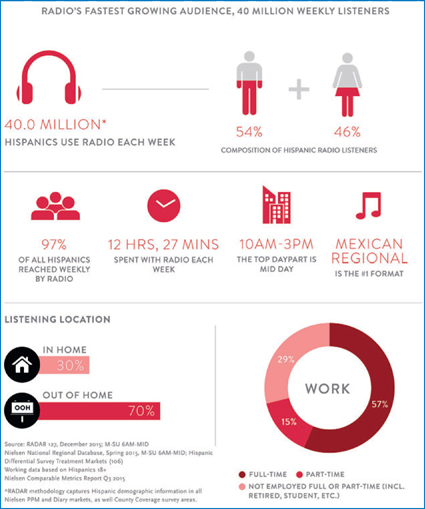

Hispanic

Hispanic or Spanish-language stations constitute another large ethnic format, reaching 40 million persons weekly, an impressive 97% of Hispanic listeners. KCOR-AM, San Antonio, became the first All-Spanish station in 1947, just a matter of months after WDIA-AM in Memphis put the black format on the air. Cities with large Latin populations are able to support the format, and in some metropolitan areas with vast numbers of Spanish-speaking residents—such as New York, Los Angeles, and Miami—several radio outlets are devoted exclusively to Hispanic programming. Nielsen Audio predecessor Arbitron reported in 2008:

As their population continued to surge in the United States, Hispanics increased the percentage of their representation in 15 of the 20 non-Spanish language formats in our report, averaging 1.1% more in audience composition than in spring 2006. The only formats where Hispanics made up a smaller proportion of a format’s listenership were UC, Oldies, Alternative and Active Rock.

FIGURE 3.8

Hispanic listenership: Radio’s fastest-growing audience. Ranking of sources listeners use to keep up to date with music

Source: Courtesy of Nielsen Audio

Programming approaches within the format are not unlike those prevalent at Anglo stations. That is to say, Spanish-language radio stations also modify their sound to draw a specific demographic. For example, many offer contemporary music for younger listeners and more traditional music for older listeners. Talk-intensive formats parallel those popular with English-language stations and the approaches are similarly segregated by Nielsen. Thus, advertisers are able to differentiate and effectively target listeners who prefer Spanish news/talk from other Spanish-language formats including sports, religious, and variety.

Houston-based consultant Ed Shane observed in 2013 that Hispanic radio is diverse and vibrant, and reflected an impressive multiplicity of programming styles and approaches. He cited Houston as an example of market diversity, where two brands of tejano, one of exitos (hits), a lot of ranchera, and a couple of talk stations vie for listeners. Miami, by way of contrast, is a top market in which tropical is the dominant Hispanic, and is programmed on two outlets. Yet tropical is absent from the roster of formats found in Houston, where regional Mexican and Spanish contemporary occupy places within the top 10 of 12+ listeners.

Spanish media experts predicted that there would be a significant increase in the number of Hispanic stations through the 2000s, and they were right. Much of this growth occurred on the AM band but later spread rapidly on FM. Leading the station count is the Mexican regional format, found on close to 400 stations. The format ties urban contemporary (UC) for tenth place of Nielsen Audio’s 2016 ranking of top formats, and is heard by an estimated one in five Hispanics. In terms of listenership, males slightly outnumber females.

Ethnic

Hundreds of other radio stations countrywide apportion a significant piece of their schedules (more than 20 hours weekly) to foreign-language programs in Portuguese, German, Polish, Greek, Japanese, and so on. Nielsen Audio characterizes this program approach “world ethnic.” Around 30 stations broadcast exclusively to American Indians and Eskimos and are licensed to Native Americans. Today, these stations are being fed programming from the AIROS Radio Network, and other indigenous media groups predict dozens more Indian-operated stations to be broadcasting by the end of the next decade. Meanwhile, the number of stations broadcasting to Asians and other nationalities is rising.

FIGURE 3.9

Ranking of sources listeners use to keep up to date with music

Source: Courtesy of The Infinite Dial 2017 from Edison Research and Triton Digital

Full Service

The full service (FS) format (also called variety, general appeal, diversified, etc.) attempts to provide its mostly middle-aged listeners a mix of all programming genres—news, sports, and information features blended with a selection of adult-oriented, pop music standards. This something-for-everyone approach initially straddled the “middle of the road” musically and subsequently became known as MOR. Over time programmers have strengthened the format’s public service aspect with the inclusion of additional information programming. It is really one-stop shopping for listeners who would like a little bit of everything. Today, this type of station exists mostly in small markets where stations attempt to be good-citizen radio for everyone, although listeners tend be 40 years and above in age. It has been called the bridge format because of its “all things to all people” programming approach. It has lost much of its large-market appeal and effectiveness due to the diversification and rise in popularity of specialized formats. In some major markets, the format continues to do well in the ratings mainly because of strong on-air personalities. But this is not the format that it once was.

FIGURE 3.10

A striking visual identity for Niijii Radio

Source: Courtesy of KKWE

FS is the home of the on-air personality. Perhaps no other format gives its air personnel as much latitude and freedom. This is not to suggest that FS announcers may do as they please. They, like any other announcer, must abide by format and programming policy, but FS personalities often serve as the cornerstone of their station’s air product. Some of the best-known deejays in the country have come from the FS (MOR) milieu. It would then follow that the music is rarely, if ever, presented in sweeps or even segued. Deejay patter occurs between each cut of music, and announcements are inserted in the same way. News and sports play another vital function at these stations. During drive periods, FS often presents lengthened blocks of news, replete with frequent traffic reports, weather updates, and the latest sports information. Many FS outlets are affiliated with professional and collegiate athletic teams. With few exceptions, FS is an AM format. Although it has endured ratings slippage in recent years, it will likely continue to bridge whatever gaps may exist in a highly specialized radio marketplace.

Niche and HD2 Formats

When it comes to format prognostication, the term unpredictable takes on a whole new meaning. Indeed, there will be a rash of successful niche formats in the coming years due to the ever-increasing fragmentation of the radio audience, but exactly what they will be is anyone’s guess. A common thread that weaves throughout the discussion is the almost surety that format experimentation is more active on the AM, satellite, and HD bands and less so on FM. For example, several years ago Radio Disney largely withdrew from radio station ownership, opting instead to deliver its programming via HD. Xperi, the parent of HD Radio, disseminates Radio Disney over a de facto network it created, utilizing the HD2 bands of medium- and large-market stations owned by CBS, Beasley, and Entercom.

New niche or splinter formats emerge frequently—bluegrass, Christian talk and K-Mozart classical are good examples—in an industry always on the lookout for the next big thing and competing with a myriad of other listening options. In terms of future format innovations, the rollout of HD2 and HD3 side channels (see the discussion of HD Radio in Chapter 9) has contributed somewhat to the development of new niche formats. Whether formats such as Russian American or traditional Christian hymns could become successful as primary channel services is debatable, but a recent perusal of the HD Radio Station Directory reveals that these formats have found a home on HD2 side channels. Experts remain divided in their opinions about the role that HD Radio plays in enlarging format diversity. Experimentation with an even wider variety of listening choices is evident with online radio, where many formats are streamed exclusively by the pureplays. A useful portal for discovering the variety of programming available from Internet-only radio stations is maintained by Grace Digital, a manufacturer of Internet radio tuners, at https://myradio.gracedigital.com.

FIGURE 3.11

Nielsen estimates more adults use radio each month than any other media form

Source: Courtesy of Nielsen Audio

As far as the future goes: who knows? Radio is hardly a static industry, but it is one that is subject to the whims of popular taste. When something new captures the imagination of the American public, radio responds, and often a new format is conceived.

Public Radio

Like numerous college stations, most public radio outlets are noncommercial in operation and program in a block fashion. That is to say, few employ a primary (single) format, but instead offer a mix of program ingredients, such as news/information and entertainment features. National Public Radio (referenced nowadays as “NPR” during the network’s on-air identifications), American Public Media, Public Radio International, and Public Radio Exchange, along with state public radio systems, provide a myriad of features for the hundreds of public radio facilities around the country. Topping the list of prominent music genres are classical and jazz. Public radio news broadcasts, among them NPR’s Morning Edition and All Things Considered and PRI’s The Takeaway, lead all radio in audience popularity for information focused on national and world events.

The popularity of NPR and its programming is reflected by a shift in the way that listeners access the network’s content. Pew Research Center statistics indicate that for the period 2010–16 NPR’s audience held relatively steady, fluctuating between 26 and 27 million weekly listeners. NPR continues to be a vanguard in the spread of podcast popularity, growing its weekly unique podcast total in 2015 to 2.5 million users—a 25% increase over the previous year.

FIGURE 3.12

Mike Janssen

ON PUBLIC RADIO

Mike Janssen

Public radio continues to be defined by the service’s hallmarks for decades: in-depth news and public affairs programming, along with genres of music that commercial radio largely ignores. But with digital platforms continuing to draw an ever-growing share of listeners’ time and attention, public radio stations and networks are putting more and more effort into reaching their audiences in earbuds, on smartphones and wherever the fractured media landscape is taking us next.

Despite these trends, traditional broadcast radio is far from obsolete. NPR has been touting recent gains in its radio audience, possibly bolstered in part by the intense news cycle of an election year and the ongoing aftermath of Donald Trump’s move into the White House. Anchored by NPR’s newsmagazines, Morning Edition and All Things Considered, the news format remains a staple of public radio. In 2015, nearly a quarter of public radio stations aired mostly news, according to an analysis by the Station Resource Group using NPR data. Meanwhile, public radio music formats such as classical, jazz and adult album alternative maintain a presence on hundreds of stations across the country.

But this relatively unchanging mix of programming on public radio’s FM stations belies the creative explosion taking place off air, with a good deal of that energy focused on podcasts. With origins in the early 2000s, podcasting is hardly a new technology. But the smash success of the 2014 podcast Serial—itself a spinoff of public radio’s This American Life—changed everything. The in-depth examination of the mysterious death of a Baltimore high school student riveted listeners, in turn reigniting the interest of program producers in exploring the potential of the intimate, episodic medium. Suddenly, it seemed that everyone wanted to emulate whatever it was that made Serial—and 2017 successor series S-Town—so addictive.

So far, few have cleared that bar. But NPR, American Public Media, and public radio stations have redoubled production and promotion of podcasts. Some have borrowed from Serial’s playbook to present localized variations of the cold-case inquiry. (One, American Public Media’s In the Dark, won a Peabody award in 2017.) But other station-produced podcasts are content to explore various local and regional issues while enjoying the relative freedom afforded by the podcast medium—a less formal tone, variable episode length (no pesky newscasts to work around or time posts to hit), and more flexibility with advertising than FCC limitations allow for broadcast programming. That latter factor is no small consideration. NPR in particular has enjoyed strong growth in ad revenue in recent years, thanks largely to podcast sales. No wonder the network is continuing to unveil new podcasts on a regular basis— recent popular additions include Invisibilia, Embedded, and Hidden Brain.

Given this growing split between public radio’s broadcast and digital activities, where will the medium go from here? It seems difficult to imagine a time when FM stations are no longer important to the system—they draw large audiences and still drive much of public radio’s fundraising from listeners. But some observers wonder whether the advent of self-driving cars, crazy as it may seem, could be a cloud on the horizon. If your “drive” to work someday frees you to read news on your smartphone or listen to a podcast, will you still tune into your local NPR station?

These innovations stem from the realization that today’s media consumers are getting news from a growing array of platforms and devices. Radio remains a popular medium on its own, but consumption on digital platforms continues to grow, particularly on portable devices such as smartphones and tablets. The emergence of a new platform demands that station and network leaders once again consider how to allocate resources to best take advantage of the opportunities presented. Managers often speak of the importance of being agile, innovative, and flexible as the system strives to remain relevant. Some stations paired with public television stations have responded by consolidating their newsrooms among all media, assigning their producers and reporters to create content for radio, TV, and online all at once. KPBS, a joint licensee in San Diego, was a trailblazer in this trend of “convergence.” It has had such success that it now offers “boot camps” to other stations that seek to follow its example.

What kinds of programming are filling up all of these new platforms and broadcast schedules? NPR news programming has continued to expand its reach and popularity, while news stations that can afford the expense are developing their own midday news and talk shows to complement and extend the news offerings from NPR and its competitors, Public Radio International and American Public Media. In attempts to appeal to younger listeners and ethnically diverse audiences and keep pace with the growing diversity of the American public, stations and networks have also launched shows that aim for a fresher sound or take advantage of social and mobile media.

Public radio’s traditional music formats of classical and jazz persist on many stations, while adult album alternative (also known as triple A) music has become a staple as well. But classical has lost ground on a number of stations as they have acquired or started to produce more news and talk programming. Regardless of format, for listeners seeking thoughtful, in-depth news and musical genres that get little airplay elsewhere, the lower end of the dial remains a go-to spot on FM radio and is likely to remain so for years to come.

___________________

Mike Janssen is Digital Editor for Current, the trade publication covering public and nonprofit media in the U.S. He is also Supervising Producer of The Pub, Current’s biweekly podcast about all things public media. Mike’s writing has appeared in the Washingtonian, the Washington City Paper, the LA Weekly and In These Times, among other publications. Mike lives in Washington, D.C., where he enjoys biking, cooking, and playing his banjo.

THE PROGRAMMER

PDs are radiophiles. They live the medium. Most admit to having been smitten by radio at an early age. “It’s something that is in your blood and grows to consuming proportions,” admits programmer Peter Falconi. Entercom Program Manager (PM) Brad Carson confesses to this ulterior motive: “I was always glued to (hometown station) WSMI (Litchfield, Illinois) to find out on ‘snow days’ if my school was cancelled or not. (I always rooted for cancellations.)” As a teen, Carson prepped for his first real job by producing “a series of ‘fake’ radio shows on a cassette player mixing music, announcing, and incorporating various entertaining ‘impressions’ of my high school teachers.” What was the response? “My friends seemed to think they were hilarious,” he says, “so I continued.” The customary route to the programmer’s job involves deejaying and participation in other on-air-related areas, such as copywriting, production, music, and news. Success largely depends on the individual and where he or she happens to be. In some instances, newcomers have gone into programming within their first year in the business. When this happens, it is most likely to occur in a small market where turnover may be high. On the other hand, it is far more common to spend years working toward this goal, even in the best of situations. “Although my father owned the station,” recounts longtime PD Brian Mitchell, “I spent a long time in a series of jobs before my appointment to programmer. Along the way, I worked as station janitor, and then got into announcing, production, and eventually programming.”

Experience contributes most toward the making of the station’s programmer. However, individuals entering the field with hopes of becoming a PD do well to acquire as much formal training as possible. The programmer’s job has become an increasingly demanding one as a result of expanding competition. “A good knowledge of research methodology, analysis, and application is crucial. Programming is both an art and a science today,” observes general manager Jim Murphy. Programmer Andy Bloom concurs with Murphy, adding, “A would-be PD needs to school himself or herself in marketing research particularly. Little is done anymore that is not based on careful analysis.”

Radio Ink publisher B. Eric Rhoads echoes this stance: “The role has changed. The PD used to be a glorified music director with some background in talent development. Today the PD must be a marketing expert.” The complexity of radio marketing has increased, due in particular to the juggernaut of social media, which, along with database marketing activities, have helped elevate the PD to the role of brand manager. “Radio itself is changing,” Rhoads added, “and the PD must adapt. No longer will records and deejays make the big difference. Stations are at parity in music, so better ways must be found to set stations apart.” In Radio Ink, the industry newsmagazine he publishes, Rhoads reported that Saga Communications, a corporate operator of 90 AM and FM stations, adopts the “brand manager” title, applying it to personnel formerly known as “program directors.” The charge to the brand manager: take ownership of all delivery platforms and extend your oversight of content beyond the air signal by proactively managing your online presence as well as your social media activities.

The concept of “brand management,” when applied to a day in the life of programmer Brad Carson’s world, means taking on multiple responsibilities:

My normal day includes writing and producing promotional announcements and station “imaging”, creating marketing plans/promotions with clients and creative partners, logistical planning for talent who are traveling around the country covering sports, deejaying, and even voice tracking a radio show in another city. In the last three years creative planning and marketing have become more important. If you don’t understand the nuts and bolts of what talent do and put into the best shows, you’re not going to be a strong programmer. There are some obvious “tricks of the trade” that we use to create the secret sauce just like every brand. Talent coaching and creativity are at a premium.

Cognizant of this change, schools with curricula in radio broadcasting emphasize courses in audience and marketing research, as well as other programming-related areas. An important fact for the aspiring PD to keep in mind is that more persons than ever before who enter broadcasting possess college degrees. Even though a degree is not necessarily a prerequisite for the position of PD, it is clearly regarded as an asset by upper management. Joe Cortese, syndicated air personality, contends that:

It used to be that a college degree didn’t mean so much. A PD came up through the ranks of programming, proved his ability, and was hired. Not that that doesn’t still happen. It does. But more and more the new PD has a degree or, at the very least, several years of college. … I majored in communication arts at a junior college and then transferred to a four-year school. There are many colleges offering communications courses here in the Boston area, so I’ll probably take some more as a way of further preparing for the day when I’ll be programming or managing a station. That’s what I eventually want to do.

FIGURE 3.13

Program directors’ cubicles inside the programming bullpen at SiriusXM offices in Washington, D.C.

Source: Courtesy of SiriusXM and Marlin Taylor

Cortese adds that experience in the trenches is also vital to success. His point is well taken. Work experience does head the list on which a station manager bases his or her selection for PD. Meanwhile, college training, at the very least, has become a criterion to the extent that, if an applicant does not have any, the prospective employer takes notice.

THE PD’S DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Where to begin this discussion poses a problem because the PD’s responsibilities and duties are so numerous and wide-ranging. Tommy Castor views it this way: “I don’t have a large staff, but large expectations, and so it can be very easy for me to fall into the mentality that I need to always do everything I possibly can to improve my radio station.” Second in responsibility to the general manager (in station clusters, the individual station programmer reports to the director of operations, who oversees all programming for the various stations), the PD is the person responsible for everything that goes over the air. This involves working with the station manager or director of operations in establishing programming format policy and overseeing its effective execution. In addition, he or she hires, mentors, and supervises music and production personnel, plans various schedules, manages the programming budget, develops promotions (in conjunction with the promotion or marketing director, if there is such a person in this role), monitors the station and its competition, assesses research, and may even pull a daily air shift. The PD also is accountable for the presentation of news, public affairs, and sports features, although a news director is often appointed to help oversee these areas.

The PD alone does not determine a station’s format. This is an upper management decision. The PD may be involved in the selection process, but, more often than not, the format has been chosen before the programmer has been hired. For example, the ownership and management of fictitious station WYYY has decided on the basis of declining revenues that the station must switch formats from country to CHR to attract a more marketable demographic. After an in-depth examination of its own market, research on the effectiveness of CHR nationally, and advice from a program consultant and national advertising rep company, the format change is deemed appropriate. Reluctantly, the station manager concludes that he must bring in a CHR specialist, which means that he must terminate the services of his present programmer, whose experience is limited to the country format. The station manager advertises the position availability in various industry trade publications and their websites, interviews several candidates, and hires the person he or she feels will take the station to the top of the ratings. When the new PD arrives, he or she is charged with the task of preparing the new format for its debut. Among other things, this may involve hiring new air talent, acquiring a new music library or updating the existing one, creating and producing promos and purchasing jingles, developing external promotions and a social media presence, and working in league with the sales, traffic, and engineering departments for maximum results.

On these points, Corinne Baldasano, Senior Vice-President of Programming and Marketing for Take On The Day LLC, observes:

First of all, of course, you must be sure that the station you are programming fills a market void, i.e., that there is an opportunity for you to succeed in your geographic area with the format you are programming. For example, a young adult alternative Rock station may not have much chance for success in an area that is mostly populated by retirees. Once you have determined that the format fills an audience need, you need to focus on building your station. The basic ingredients are making sure your music mix is correct (if you are programming a music station) and that you’ve hired the on-air talent that conveys the attitude and image of the station you wish to build. At this stage, it is far more important to focus inward than outward. Many stations have failed because they’ve paid more attention to the competition’s product than they have their own.

Once the format is implemented, the PD must work at refining and maintaining the sound. The deejay staff must be monitored and mentored to ensure the cohesiveness of the on-air product. Speaking about the importance of good mentoring, Leslie Whittle, PD of Houston’s 104.1 KRBE, says, “It’s absolutely necessary to the future of any business to mentor.” Named “One of the Best Program Directors in America” by Radio Ink in 2016, Whittle explains that mentoring is an activity that can extend beyond on-air performance review and coaching:

This doesn’t only take time, it takes understanding of the goals and capabilities of those you mentor. What do they REALLY want? A career as a Program Director? To be a DJ? To produce audio? Do they want to hear their music on the radio? Put together great events for clients? And most importantly, CAN you help them accomplish these goals with the right guidance? Today’s technology means less chances to get on-air experience, so it’s more important than ever now to know the potential of those you mentor.

After a short time, the programmer may feel compelled to modify air schedules either by shifting deejays around or by replacing those who do not enhance the format. Efforts to maintain consistency between the weekday and weekend “sound” of the station also have to be made. The PD prepares weekend and holiday schedules as well and this generally requires the hiring of part-time announcers. A station may employ as few as one or two part-timers or fill-in people or as many as eight to 10. This largely depends on whether deejays are on a five- or six-day schedule, as well as the extent to which the station utilizes automation and voice-tracking (see Chapter 8). Air personnel often are hired to work a six-day week. The objective of scheduling is not merely to fill slots but to maintain the continuity and consistency of sound. A PD prefers to tamper with shifts as little as possible and fervently hopes that he has filled weekend slots with individuals who are reliable. Brian Mitchell says:

The importance of dependable, trustworthy air people cannot be overemphasized. It’s great to have talented deejays, but if they don’t show up when they are supposed to because of one reason or another, they don’t do you a lot of good. You need people who are cooperative. I have no patience with individuals who try to deceive me or fail to live up to their responsibilities.

A station that is constantly introducing new air personnel has a difficult time establishing listener habit. The PD knows that to succeed he or she must present a stable and dependable sound, and this is a significant programming challenge, albeit one that has been mitigated somewhat by the practice of voice-tracking “unstaffed” overnight and weekend air shifts. The techniques of voice-tracking assist the PD in maintaining a consistent 24/7 on-air sound.

Programmer Brad Carson defends the practice: “Talent-sharing from station to station,” he says, “using voice-tracking and other methods (networks, for example) has helped many stations, regardless of market size or format, put the best voices and talent in radio markets across America.” Detractors of voice-tracking criticize the practice, claiming that owners’ primary objective in eliminating local talent is the reduction of expenses. Carson, however, believes that this viewpoint can be inconsistent with a PD’s objectives:

While many have demonized voicetrackings and network radio because of cost reduction (which is not always the case when using these tools) radio groups want to put the very best content on the air. Content is still king. High quality content and entertaining content are always the goal.

Marlin R. Taylor, Founder of Bonneville Broadcasting System and veteran major-market station programmer and manager, underscores the need for station personnel to support their nonlocal air talent:

In most cases, if a station is to truly stay connected to the listener, “local” is an element that must be factored in. If you’re talking about a voice-tracker from outside the market, he/she needs to be provided with information that enables the person to include content relevant to the local community. If it’s a network music show, there should be timely local information included in the local breaks beyond just commercial spots. Otherwise, a properly run station that utilizes either of these extensively on weekends and even overnight hours needs to have someone available to communicate information should an emergency or other major newsworthy event occur in the community or region that the listener should be aware of.

PD/midday air personality Randi Myles of Detroit’s Praise 102.7 notes not only that successful programming must be local, but that the programmer should be sensitive to the innate needs of listeners. She explains:

Programming radio is a way to cater to the overall ‘needs’ for the market you work in. In my case, Inspirational music caters to those who love gospel music, who go to church (mostly) or for the person who needs to be lifted up after a hard day or unfortunate situation. That is a small group of people in some areas, but in a larger market like Detroit … it’s a bigger group of listeners. The same goes for any format really. You look for the need and then program the station accordingly.

FIGURE 3.14

Mike McVay

MARKET-BASED PROGRAMMING DECISION-MAKING

Mike McVay

The decision to shift programming decision-making authority and control from the corporate level to that of the markets was less about a strategy and more about a tactic. We at Cumulus needed to do it if we were to turn around the ratings of our company. Our CEO, Mary Berner, assigned us the task of “fixing” programming in order that we could improve the ratings, thus improving our advertising sales efforts and growing revenue. This meant a restructuring of how we approached the product side of the business and the quality or level of the individuals we would retain or hire to program our stations.

Our company was out of step with what our competitors were doing. There was some good and some bad with that. The way in which many stations in North America were programmed had gone full circle. Many USA broadcast companies, prederegulation, owned only seven AM and seven FM stations. That was the maximum permitted by the Federal Communications Commission. Stations operated very much unto themselves and were specifically tailored to their markets. Like with anything, there were exceptions, but stations tended to operate independent of each other beyond carrying specific group products like the news. When the ownership cap was extended, radio started to become much more systematized, and while systems are necessary some companies took it to the extreme. They eliminated the ability to focus closely on the uniqueness of an individual market. It eliminated the individuality among programmers and talent, and stifled creativity.

The good in how the company previously operated was that the highest-ranked programmer in the company, my then-director, is a creative person who wasn’t afraid to develop new products and “throw them against the wall to see if they’d stick.” What was bad about it was that we didn’t allow time or provide resources for research and development. A new product was thought of and the program was launched. In some cases it was in a massive fashion across multiple stations and network channels. The level of success varied greatly as these individual markets were so different from one another. In some cases we changed the format and/or name of a heritage radio station and launched a new product without marketing or promotional support. That’s 180 degrees off of what one should do when preparing to launch a new product.

We began the programming turnaround when the CEO announced the decentralization of programming at Cumulus. Her statement to the company was “Programming is the oxygen of Cumulus.” There it was. The focus on having the best product and the importance of programming to turn around the business. We began by creating the Office of Programming (OP). I am the creative side of that office. My team, and ultimately me, is responsible for everything that comes out of the speakers. The administrative side rests with my partner in the OP, Bob Walker. He handles the sales interface, works with market managers and is business and operationally focused.

Giving the power to program back to the program directors, and enabling the market managers to be involved in programming decisions has created a collaborative spirit within the company. It also has heightened the awareness of the need for individuals to accept responsibility for the ratings. To that end we evaluate our programmers’ performances twice yearly. We provide them with tools to improve should there be such a need. We created a structure that enables them to be creative.

We are employing many of the philosophies, systems and tactics that my former programming consulting company (McVay Media) used in improving the product on client stations. That is, to focus on music or talk (sports and/or news talk) content that provides instant gratification. Every time I hit the button for your station I hear a topic I am attracted to or a song that I like. It’s information that satisfies one’s need for survival information and answers the question “what’s happening today?” Personalities that are relatable people. They live in the listeners’ world. They must work hard to be better prepared and better informed than their competition. Building day-to-day tune-in. If I don’t listen, I will miss something. Great experiential contests that make the winning experience shared as we live through the fantasy of that one person who won. Marketing tactics designed to accomplish your rating goal and satisfy a specific need of the audience. We preach these philosophies on our weekly sharing conference programming calls.

A focus on opportunity development, providing resources like research, and launching an ongoing education program that shares “best practices” for multiple facets of programming. Our focus is on music, content, information, personality, promotion, and marketing. We’ve enabled programmers to select and air the music that they feel is proper for their audiences. We’ve enabled programmers to select the talent that they want for their stations, develop contests and promotions that can attract an audience, and we’ve allowed them to decide how best to image their radio stations. They are responsible for the success or failure of their stations and as such must be prepared to accept such responsibility.

What we do not do is abandon our programmers. Our structure is that there are three individuals who are vice-president/Programming Operations that oversee “buckets” of markets. Their job is to look at an entire cluster of stations in a market, determine how they best fit together versus the competition, and provide a more global view. We have three researchers who provide us with insight into the ratings, the content and lead us in SWAT analysis when a station is underperforming or showing poor performance. We have two individuals who focus on training. Their role is to look at what works in what situations and share that information as well as teach “best practices.” We also have VP/formats who serve as consultants. They are experts in music and talk formats. They’re the support that a programmer has available to use when they desire a different perspective or are simply looking for guidance. These systems are designed to allow a program director to conduct daily business without eliminating the time to be creative.

The significance of this shift is that programmers can now develop and create content that is attractive to their specific markets. The decentralization of programming has enabled PDs to be more reactive to the competition, to be proactive in creating new concepts and programs and to work more closely with sales in designing advertiser-friendly programming that is not detrimental to the ratings.

Our focus is beyond the FM and AM bands. We’re developing content for online, on-demand and podcasting. We’re creating new and unique programming for our HD2 channels. These blank canvasses require new thinking, new perspectives and the type of no-boundaries thinking that comes from youth. Our success, 15 months of continual rating increases (as of this writing), will lead other companies to adopt our decentralized approach. That means more opportunities for individuals who possess the vision to be creative while not losing the discipline to be responsible.

___________________

Mike McVay is Executive Vice-President/Content and Programming for Cumulus Media and Westwood One. He oversees the programming of 450 radio stations and two radio networks. He is a veteran 40-year programmer with consulting, management, ownership, sales, programming and on-air experience. In addition he has developed and launched several nationally syndicated programs. As an international consultant he has programmed more than 300 stations. McVay has received numerous awards and acknowledgments, and is the recipient of the prestigious Rockwell Award. Radio Ink ranked him #4 among America’s top programmers and he was named one of the titans of talk by NTS magazine every year 2012–16.

Production schedules also are prepared by the programmer. Deejays are usually tapped for production duties before or after their airshifts. For example, the morning person who is on the air 6–10 am may be assigned production and copy (commercial scriptwriting) chores from 10 am until noon. Meanwhile, the midday deejay who is on the air from 10 am until 3 pm is given production assignments for 3–5 pm, and so on. Large radio stations frequently employ a full-time production person. If so, this individual handles all production responsibilities and is supervised by the PD.

A PD traditionally handles the department’s budget, which generally constitutes 30–40% of the station’s operating budget. Working with the station manager, the PD ascertains the financial needs of the programming area. The size and scope of the budget vary from station to station. Most programming budgets include funds for the acquisition of program materials, such as subscription music services, network and syndicated program features, and contest paraphernalia. A separate promotional budget usually exists and this too may be managed by the PD. The programmer’s budgetary responsibilities range from monumental at some outlets to minuscule at others. Personnel salaries and even equipment purchases may fall within the province of the program department’s budget. Thus, Brian Mitchell believes that “an understanding of the total financial structure of the company or corporation and how programming fits into the scheme of things is a real asset to a programmer.”