9

Myth – Crypto Empowers Crime

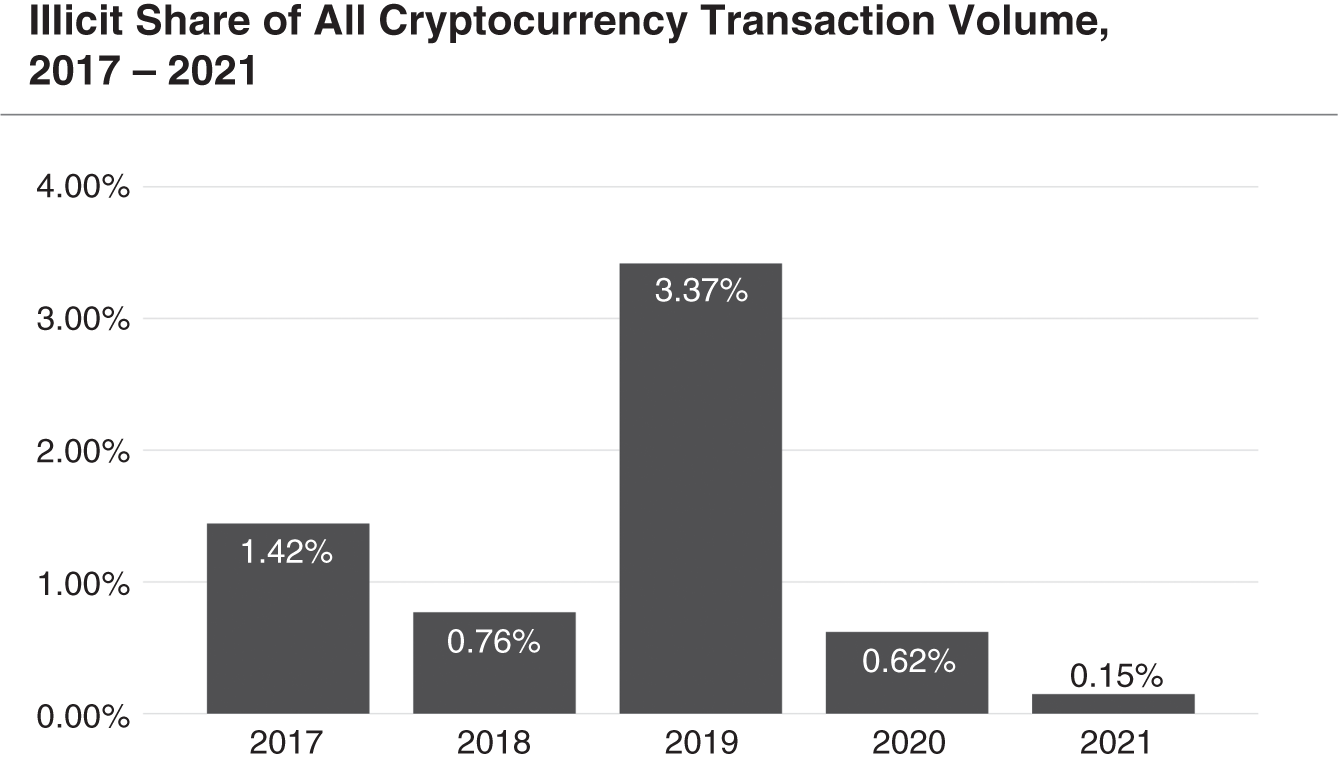

“Crypto is only used for illegal activity” is something people love to say at cocktail parties and boardrooms. As we debunked Professor Krugman in Chapter 7 regarding this issue, we are here to set this myth aside. Just like a camera or a hammer, crypto is a tool, and a tool serves the agenda of the one who wields it. If you look at the numbers, it's clear that most crypto is not used for criminal activity. According to a 2022 report from Chainalysis, criminal activity represented 3.4% of all cryptocurrency transaction volume in 2019. In 2020, the criminal share of all cryptocurrency activity fell to just 0.62%. There is far more crime involved in the use of dollars; it's just not new or sexy. We would argue that a hundred‐dollar bill is more dangerous simply because it is used so much more often.

In the Chainalysis report on the year 2021, the trend continued. “Across all cryptocurrencies, total transaction volume grew to $15.8 trillion in 2021, up 567% from 2020's totals. Given that roaring adoption, it's no surprise that more cybercriminals are using cryptocurrency. But the fact that the increase of illegal activity was only 79% – nearly an order of magnitude lower than overall adoption – might be the biggest surprise of all.”1 Chainalysis found that with the growth of legitimate crypto far outpacing the growth of criminal usage, illicit activity's share of cryptocurrency transaction volume has never been lower. As cryptocurrency growth and use continues, we can expect there to be some portion that is related to crime and illicit activity. That's just how the world is. But what is not often realized is that crypto adoption is growing at a faster rate than illicit activity, which means that the relatively small proportion of illegal activity continues to decline relative to the market size.

Of course, the headlines are sensational. That same set of facts was republished in a Fortune article, but with the sensational headline “Crypto Crime Just Hit an All‐Time High of $14 Billion.” That may be true, but it is misleading, and it fuels opinions for those who don't take the time to digest the full content. Forbes pursued the topic in like form with the article “Cryptocurrency Fuels Growth of Crime.” It's Forbes, so it must be true, right? Upon actually reading the article we find something a little different:

Cryptocurrency utilization is exploding, most of it unrelated to criminal activity. It is certainly true that crypto‐related crime has grown; one respected vendor reports it nearly doubled from 2020 to 2021, reaching an all‐time high of $14 billion. That same vendor reports even more dramatic growth of overall cryptocurrency transactions, which was more than five times in the same period. As the vendor says: “Transactions involving illicit addresses represented just 0.15% of cryptocurrency transaction volume in 2021 despite the raw value of illicit transaction volume reaching its highest level ever.”2

We see this summarized, over time, in Figure 9.1.

It's worth noting that this data is from Chainalysis' excellent report on crypto and crime, which we encourage readers to dive into if they want to go deeper.

This information is supported by research done by the RAND Corporation, which noted in a recent study on the perceived attractiveness of cryptocurrencies for money‐laundering purposes that 99% of cryptocurrency transactions are performed through centralized exchanges, like Coinbase, which can be subject to regulation like traditional banks or exchanges.

So where does all the concern come from? Like many areas of crime, crypto crime shot up during the pandemic and there have been several high‐profile crypto crimes – exchanges getting hacked, kidnappers demanding to be paid in crypto, the fraud cases discussed earlier. These disturbing stories distort the overall public understanding of crypto.

Figure 9.1 Crypto and Crime

Source: Chainalysis.

We want to pause for a moment here and be clear: it's not acceptable that crypto has been used in organized criminal and violent activities – not acceptable to us, law enforcement worldwide, or investors of any stripe. We're encouraged by the international cooperation among law enforcement agencies in successfully foiling the efforts of numerous crypto criminal gangs. We're not saying crime does not exist. We are saying it's not at the sensational level at which it is promoted.

As an emerging technology that was outside the banking system, early Bitcoin and fly‐by‐night token offerings certainly drew the kind of people who exploit early‐stage technology to do misdeeds, just like the first banks and stagecoaches on the American frontier drew robbers.

In addition, although criminals are the same people who prefer hundred‐dollar bills to hoard and hide their feloniously acquired cash, the Fed hasn't banned Benjamins and we all still use paper currency. Kidnappers are paid in cash, but still we do not ban it for other uses. By the same token, legitimate uses of crypto shouldn't be banned, either.

The Internet Is a Criminal Battlefield

In many respects, however, illegal usage of cryptocurrency and DeFi assets is paltry compared to that of the Internet, which changed the way we think, communicate, and exist in the world, but is also a tool for crime. Europol is the European Union's elite cyber‐crime‐fighting agency, and their Internet Organized Crime Threat Assessment (IOCTA) is the platinum standard for tracking cybercrime trends. The IOCTA reported that in 2020 Europe saw the proliferation of crime‐as‐a‐service cyberattacks, more ransomware attacks with “extra layers of extortion,” and expanding use of “gray infrastructure enhancing criminals' operational security” (that is, “legal” services located in countries with a history of not cooperating with international law enforcement). These services are used by criminals and advertised in criminal forums. Examples of gray infrastructure services include unhackable servers, rogue cryptocurrency exchanges, and VPNs that provide safe havens. And it's not just these gray areas or sophisticated organizations. Anyone can google how to build a bomb and voilà, information appears. Do criminals use that information? Of course. Does that mean it's the only thing the Internet is used for? Of course not. The cost of worldwide Internet‐enabled and ‐driven crime is in the trillions of dollars per year.

In contrast, crime is becoming a smaller and smaller part of the cryptocurrency ecosystem. Law enforcement in the United States and worldwide has deepened its bench and grown smarter about the transparent nature of blockchain as a crime‐fighting tool, often hiring IT code breakers and crypto hackers to turn the tables on criminal organizations. We think it's important to keep this perspective. If crime is a measure of whether we should have a technology, then, well, we'd really not have any technology. If we throw the baby out with the bathwater, we all lose.

Tracing the Untraceable

In 2021, the Justice Department displayed its growing sophistication regarding the cyber world when it busted the criminals who hacked the Colonial Pipeline Company and recovered most of the ransom paid by the oil products company. In a blow to the “only criminals use crypto because it's untraceable” narrative, the FBI recovered almost 63.7 of the 75 bitcoin paid in ransom by tracking it. Yes, it was tracked. Despite everyone's attempt to say Bitcoin is anonymous, as we have discovered, it is really pseudonymous. Transactions are masked and the transactor's identity is generally not visible. Ultimately, however, if you onboard and offboard at any exchange or any system that requires a know your customer (KYC) process, your data can be tracked to you. Everything has a starting point and everything has an endpoint. Crypto is about empowering individuals to have freedom and flexibility without central control. This does not mean that it's immune to observation, laws, and common sense, as our ransomware attackers found. This was also discovered, much to their chagrin, by “Razzelkhan” and “Dutch,” a couple who seemingly thought they would be able to move billions in bitcoin without anyone noticing. Let's explore just how this unfolded in both of these cases.

Ransomeware? Ransomthere!

The Russian hacker gang DarkSide ran the operation, attacking Colonial's computer network and embedding ransomware, resulting in the freezing of Colonial's pipeline on the East Coast. DarkSide harvested private and sensitive information, threatened to release it, adding blackmail to the list of its offenses, and demanded 75 bitcoins in their scheme. Colonial Pipeline executives decided to pay the ransom of 75 bitcoins while immediately notifying the FBI.

Agents traced DarkSide's bitcoin dealings by reviewing transactions on Bitcoin's blockchain, its public ledger. During the review, agents identified 63.7 bitcoins in a digital wallet linked to one of the members of DarkSide. To access the digital wallet, the FBI obtained a private key to recover the funds, although the FBI did not disclose its sources or the methods it used to obtain the private key to the digital wallet.

The FBI's seizure was the first time federal law enforcement recovered a ransomware payment since the U.S. Department of Justice created the Ransomware and Digital Extortion Task Force in April 2020 to target ransomware attacks and actors and recover ill‐gotten gains.

“Following the money remains one of the most basic, yet powerful tools we have,” said DOJ deputy attorney General Lisa O. Monaco. “Ransom payments are the fuel that propels the digital extortion engine, and [this] demonstrates that the United States will use all available tools to make these attacks more costly and less profitable for criminal enterprises. We will continue to target the entire ransomware ecosystem to disrupt and deter these attacks.”

The New York Times followed:

… for the growing community of cryptocurrency enthusiasts and investors, the fact that federal investigators had tracked the ransom as it moved through at least 23 different electronic accounts belonging to DarkSide, the hacking collective, before accessing one account showed that law enforcement was growing along with the industry.

That's because the same properties that make cryptocurrencies attractive to cybercriminals – the ability to transfer money instantaneously without a bank's permission – can be leveraged by law enforcement to track and seize criminals' funds at the speed of the internet.”3

Not Hiding in Plain Sight

DarkSide's ransomware was evocative of the shadowy criminal organization, but crimes are not always so obviously … dark. Sometimes they are just people capitalizing on greed and sometimes they are just downright weird. We have a couple who meets both of those criteria in one of the greatest grabs turned blunder in history.

Meet Heather “Razzlekhan” Morgan, the self‐styled rapper and “Crocodile of Wall Street,” and her “mentalist” investor, Russian husband Ilya “Dutch” Lichtenstein, alleged money launderers of the highest order, although on the surface they seemed anything but.

Morgan and Lichtenstein in 2016 deployed social media to promote themselves as financial hipsters while hatching a scheme to launder $4.5 billion in bitcoin stolen from the exchange Bitfinex. Razzlekhan is known for almost unwatchable rap (google at your own risk) with lyrics that painfully sort of rhyme but are about as appealing as a partially open banana that has been sitting in the sun for two weeks. As noted in Bloomberg, “It seems unlikely that someone who tried to rhyme ‘Razzlekhan's the name’ with ‘that hot grandma you really wanna bang’ could in fact be a master thief. Then again, this is the crypto world, where a lack of experience or competence hasn't always been a barrier.” Perhaps a better clue was in the also tepid but revealing lyric “Spearphish your password / All your funds transferred.” Bad taste, however, isn't a crime, so how did the couple get linked to one of the biggest crypto hacks in history?

It starts with an exchange. In 2016 the cryptocurrency exchange Bitfinex was hacked, and 100,000 bitcoins were stolen. The criminals were very good and lurked in the exchange for weeks until getting access to private keys that would allow them to transfer the bitcoin to external wallets. They then cleaned up their tracks and “poof” were gone. Sort of. The funds remained in plain sight in the wallets because, as we've discussed, blockchains are transparent. Eventually, the money moved and federal agents, including IRS investigators, conducted crypto‐forensic analysis to trace the stolen funds:

- Through an unhosted crypto wallet containing over 2,000 Bitcoin addresses

- To accounts at the darknet market AlphaBay

- To seven interconnected virtual currency exchange accounts

- To various unhosted Bitcoin wallets

- To accounts the couple owned at six other virtual currency exchanges

- The last link, a $500 gift card to Walmart (yes, Walmart)

The Walmart card was sent to a Russian‐registered email address that investigators were able to link to Lichtenstein. So, in a bizzarro turn of events the alleged launderers were using money linked to the Bitfinex hack to buy daily sundries, and $3.6 billion of the $4.5 billion in stolen bitcoin was recovered with the desire to use $500.

This type of investigation is not simple. It required a huge amount of forensic work. As noted earlier in this chapter, everything has a starting point and an ending point. Eighty percent of the bitcoin that was stolen has been recovered. This brings us to a contrarian argument – bitcoin, with its transparency, is more of a deterrent to would‐be criminals. Cash, it would seem, is indeed king.

Everyone Evolves

The previous examples clearly demonstrate that cryptocurrencies are not anonymous. Every separate transaction is logged onto the blockchain, a ledger of all transactions distributed to all users in the network. Most blockchains are publicly available, making transactions traceable. This gives the authorities around the world access to substantially more information than a case involving cash. While privacy coins and several services and techniques make tracing more difficult, they by no means stop the good guys from finding out who is hiding behind the crime.

Importantly, the overall number and value of cryptocurrency transactions related to criminal activities still represent only a small portion of the illicit economy compared to cash and other transactions. The volatility of cryptocurrencies hampers widespread adoption by bad guys. Criminal networks continue to rely on traditional fiat money and transactions to a large degree, because cash isn't trackable through the Internet.

It's true that criminals have become more sophisticated in their use of cryptocurrencies. Illicit funds increasingly travel through a byzantine set of links involving financial entities, many of which are novel and thus not yet part of standardized, regulated financial and payment markets and, just as technology grows, the sophistication of criminals grows as well. Like a game of whack‐a‐mole, we think that there will always be new perpetrators, schemes, and “dark web” sites designed to move money illicitly.

We have honestly wondered, given the time, effort, and energy some of these schemes take, why the perpetrators don't just go legit. It sure seems like it would be easier. Regardless, criminals will continue to use and develop obfuscation methods and other countermeasures to exploit technology. They evolve. At the same time, everyone seems to forget that there are some pretty smart people in law enforcement as well, and they have access to the same tools the criminals do. They also evolve. So, while criminals are using the blockchain tool for their own purposes, law enforcement is doing the same thing. The point is that the tool itself is not the problem; it's the use of it. Ironically, we see that for those conducting illicit activity it may well be the silver bullet itself. In this case the “anonymous” bitcoin network is the bullet that ends up cracking the case open and ruining their nefarious plans.