THREE

Seduction and the Emotions

As a little white snake

with lovely stripes on its young body

troubles the jungle elephant

this slip of a girl

her teeth like sprouts of new rice

her wrists stacked with bangles

troubles me

Seduction Targets the Emotions

SEDUCTION IS A PROCESS THAT CAN BYPASS the rational brain, appealing to psychological mechanisms other than those involved in conscious thought. This happens for a good reason. Rational brains are expensive for animals to grow and maintain, so, for many kinds of problem, it is more efficient to rely on solutions from unconscious, emotional brain processes. A song sparrow with a brain large enough to understand the theory of evolution and calculate the fitness-maximizing choice of mate for any situation would be unable to support its vast head on its tiny neck. Instead, song sparrows have developed a small, relatively space-efficient brain that employs shortcuts—simple rules of behavior that enable the sparrow to negotiate the world reasonably well.

Human beings have stronger necks, but the principle is the same. The emotions can be thought of as natural selection's way of embodying some of the necessary rules of behavior. This understanding of some aspects of behavior has come to be known as the “somatic markers hypothesis.” Our ability to link our cognitive and emotional responses depends on functions that are now known to be concentrated in specific areas of the brain (notably the ventromedial sector of the prefrontal cortex).1 There is also a large body of scientific work exploring the role of the endocrine system in mediating social relationships.2

Hormones are not the only means by which our brains encode shortcuts: we have well-known, purely cognitive biases, too (like our tendency to see shapes and faces in the clouds), which have evolved under similar constraints. And even our ordinary cognitive decision-making abilities depend on integration with our emotions, as Antonio Damasio (the original proponent of the somatic markers hypothesis) argues in his book Descartes' Error.3 But emotions often program us to make simple but reasonably reliable responses to some frequent and important predicaments with a minimum of scope for reflection. When something frightening happens to me, my body experiences a rush of adrenalin, I feel fear, and I run away (which of these events is cause and which is effect may not always be easy to tell, as it all happens so fast). That might not be the absolutely best response in all situations (I've missed some good movies as a result), but it worked well enough for my ancestors that I am here typing this chapter today.

However, the great virtues of having the emotions direct behavioral responses to our environment—their simplicity and predictability—are also what make them less reliable when that environment changes, as well as susceptible to manipulation by others. A rule of thumb that worked well in the hunter-gatherer environment of our ancestors may be quite unsuitable for our modern environment: finding warriors sexy was once a way for a woman to increase her chances of survival and reproductive success, but in many cities it is now more likely to give her a drug dealer for a boyfriend. More important, a simple rule of behavior that makes us predictable invites others to exploit our predictability. Chief among the manipulators are advertisers: when they realize what kind of advertising we respond to, they make more of it.

Predictability may be a liability, then; but it also facilitates certain transactions. Those who advertise to us are usually not just trying to exploit us but are typically trying to persuade us to do something that is in our interests as well as in theirs (admittedly, on terms favorable to them). Such exchanges can be mutually beneficial, but each party will invest time, energy, and resources in an exchange only if the other party can be relied on. Predictability can sometimes signal reliability—an argument first developed by the economist Robert Frank and now the subject of a growing scientific literature.4 The display of emotion can therefore persuade others of our trustworthiness in a manner that surpasses the abilities of our consciously calculating brain. Suppose, for instance, that you think I am making friendly overtures to you because I have calculated that it is in my interests to persuade you to trust me. You may respond positively if you think we have interests in common. But you are right to remain wary: any change in our circumstances may upset that calculation, and then all bets are off. If instead you think I am making friendly overtures to you because I really like you, wish you well, and want to spend time with you, you may be much more confident about trusting me. The emotions can be frustratingly difficult for our rational capacity to master, granted; but sometimes for that very reason they have a persistence that is quite foreign to the foxy, calculating brain.

The fact that my emotions are removed from my conscious control is, paradoxically, a strength when it comes to persuading others to trust me. If that's true of ordinary friendships, it's even more true of human sexual relationships, which offer vast gains from cooperation. Those gains will depend on investments made by both parties, and it may not be worth embarking on the relationship at all without an assurance of some commitment. A visibly emotional attachment to you may be a much more credible assurance that your partner will stay around after you've had sex than any amount of reasoned argument on his part. Before the invention of contraception, the risk of pregnancy meant women bore a significant cost in embarking on sexual relationships without some assurance of commitment from men; men, in turn, might balk at such commitments without an assurance of paternity from women. Emotions as signals of commitment could therefore have powerful adaptive value.

Managing emotions so that they are simple enough to be trusted by those who want to cooperate with us but complex enough not to be easily manipulated by those who want to cheat us is a difficult balance for natural selection to get right. And the balancing point would have changed as the arms race between cheaters and honest signalers became more sophisticated over time. The result is that many of our emotional responses are a baffling mixture of the solid and the inscrutable. The solidity explains why we can be faithful and loyal but also why we so often engage in insidiously repetitive behavior with those to whom we are sexually attracted—why we can be so slow to learn that it's time to move on. The inscrutability is the fruit of our continual effort to project ourselves as better (stronger, cleverer) than we are, and it explains both the charm and the frustration of so many exchanges of sexual signals, their playful quality, the fact that nothing can be taken for granted. Why does she give him the come-on only to draw back? Why does he seem to signal his steadiness and loyalty and then behave in completely unreliable ways? Both seem to want to signal their attraction but are afraid of being taken for the wrong sort of ride, afraid of seeming to sell themselves too cheap.

The inscrutability of so many of our sexual signals creates an ideal environment for cultural models to influence our behavior, guiding us toward some interpretations of what others may be signaling to us and steering us away from others. Stendhal describes in The Red and the Black the confusions of his young hero, Julien Sorel, and the object of his affections, the innocent Madame de Rênal, the wife of the mayor of a small provincial town in western France whose children Sorel is tutoring:

In Paris, [their] situation would rapidly have been simplified; but in Paris, love is the child of novels. The young tutor and his shy mistress would have found in three or four novels and even in the poems learned in school the clarification of their position. The novels would have set out a role to play, shown them a model to copy, and Julien's vanity would have forced him sooner or later, whether he felt pleasure in it or not, to follow the model…. In a small town in the Aveyron or the Pyrenees, the smallest incident would have proved decisive because of the fiery climate…but under these grey northern skies, an impecunious young man, who is ambitious only because his heart needs some of the joys that money can bring, spends every day in the company of a thirty-year-old woman who is truly modest and busy with her children, and never uses novels as an example to follow. Everything happens slowly in the provinces, it's all more natural.5

Novels were considered dangerous reading for young ladies in many nineteenth-century households precisely because even fictional stories could offer previously innocent women a set of methods for decoding sexual signals that might lead them astray. Nowadays, in small provincial towns, even people who read few novels are likely to take their examples from cinema. (Diego Gambetta reports that Italian mafiosi have been highly influenced in their signaling behavior by the Godfather movies, so that the mutual imitation of life and art has become in this example entirely circular.)6 The behavior of courting couples in American romantic comedies and television sitcoms has influenced styles of behavior all over the world.

It's important to understand that the confusion and opacity in the way we signal to each other, and which these cultural models help us try to decode, do not represent some kind of inexplicable dysfunction in the process. On the contrary, the process of signaling has evolved to be confusing precisely because there are many incentives to project misleading signals, and opacity and complexity are the price to pay for signals that can credibly mean anything at all. Transparency isn't a realistic ideal: even the fact that we have nothing to hide can be something we have good reason to hide.*

To see why inscrutability may be a feature rather than a bug in the human emotions, consider what Sherlock Holmes might have called The Curious Incident of the Female Orgasm, recalling the famous dog whose significance for the case was that it did not bark. One possible evolutionary explanation for the nature of orgasm in the human female (a phenomenon rare, though not unknown, in other animals) makes its legendary unpredictability part of its point.7 According to this explanation, the female orgasm developed out of the basic physiology that also enables the male orgasm. But rather than being subject to selective pressures to make it occur more predictably, it remained elusive and unprogrammable as a way of screening males for reliability.8 This must obviously have happened during a period in our evolution when it was common for women to mate with multiple men (and in which women could exercise choice over their longer-term partner or partners based on the quality of earlier encounters).9

Female orgasm, according to this view, came to be associated with hormonal changes (notably the release of the hormones vasopressin and oxytocin) that increase trusting behavior and are associated with emotional commitment.10 But like all screening mechanisms, it had to be discriminating. If the woman's orgasm could be induced only by the most attentive, considerate, and trustworthy males—the kind for whom it was worth transforming a one-night stand into a longer-term relationship—it could help her to ensure that she didn't make her own emotional commitment too easily and therefore be too easily manipulated. A woman who climaxed with more or less any male she had sex with would be either too vulnerable to manipulation (if the orgasm were accompanied by the appropriate emotional changes) or unable to use her emotions to make commitments (if it were not). From natural selection's point of view, a woman who climaxed too easily would be engaging in the sexual equivalent of grade inflation. Men don't have this problem—but then the diplomas they issue have never been worth much anyway.

It doesn't follow, of course, that the female orgasm had to perform this screening function: other mechanisms could have been found, both for screening and for encouraging commitment, and it may have been an accident that natural selection hit on this particular one. It may have had additional evolutionary advantages.11 But a physiological mechanism for screening and encouraging commitment would have conveyed a useful adaptive advantage. Unfortunately, though, natural selection has no foresight: a woman's sexual sensitivity may be calibrated to the kinds of men her female ancestors knew, but this notoriously doesn't mean it will be calibrated to the partner(s) she happens to be with at the moment.

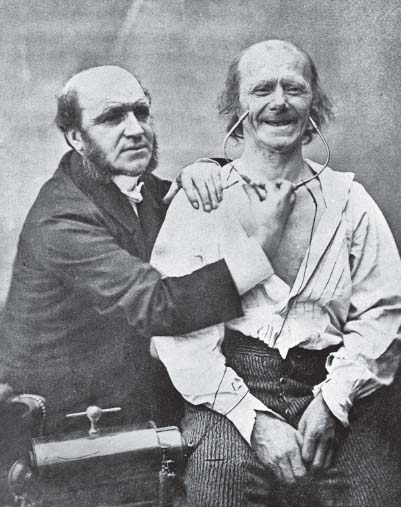

A woman's capacity for orgasm may be a form of screening males for reliability, but it is (fortunately) far from being the only skill at her disposal. She exercises other talents long before orgasm becomes even a theoretical possibility. In fact, the more closely we look, the more evidence we find in our daily lives of this interplay of ardent signaling and skeptical screening, with men and women playing both roles. Take smiling, something most of us— even economists—do hundreds of times a day. It's not used only in sexual flirtation, of course, but it plays a very important role there: a melting smile is reported by many women to be one of the sexiest things they notice about a man.12 One theory about the origins of smiling is that it evolved to signal trustworthiness.13 Flashing a “genuine” smile is difficult (though easier for some people than for others), and for nearly all of us, it is much easier to do if we are genuinely feeling relaxed and warmly disposed to the person at whom we are smiling. Furthermore, a genuine smile stimulates warm feelings in others and a willingness to trust the smiler—which would be a dangerous form of susceptibility if the smile were not a genuine signal of trustworthiness.

Smiles Are Signals Too

Together with colleagues from the Toulouse School of Economics in France and the Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Plön, Germany, I have recently been trying to test this theory of smiling in the laboratory.14 We do this using a well-known form of experiment called a trust game. One person is given a sum of money and has to choose whether to keep it or to send it to a second person, whom we can call a trustee. If the money is sent, it is immediately tripled. The trustee then has to choose whether to keep the money or to send some of it back to the original subject, the “first player.” You might think this would lead to an obvious outcome: trustees would always keep the money. But they don't always do so. If they did, and if that were what everyone expected, none of the first players would ever send the money, and the experiment would always end boringly at the first stage. It's now well known that some first players do send the money, and trustees return money often enough to justify the optimism of the first players. This outcome has been corroborated with scores of trust experiments in many different settings; in our own version, a little under 40 percent of first subjects sent money, and around 80 percent of trustees returned money.

The novelty in our version of the experiment is that before the game starts, we give our trustees the chance to make a short video clip in which they introduce themselves to the first players. We say nothing to our subjects about smiling, but almost all the trustees try hard to project a convincing smile to their viewers. Their success at doing so turns out to make a difference to how much the first players are willing to trust them by sending the money: those whose smiles are rated by viewers as in the “more genuine” half of the group receive money just over 40 percent of the time, while those who are rated as being in the “less genuine” half of the group receive money around 35 percent of the time.15 The difference, a little over 5 percentage points, is not huge, but it's big enough over time to make quite a difference to the success of the genuine smilers.16

Still, showing that genuine smiling encourages people to send you money doesn't prove that smiling is a signal of trustworthiness. Pointing a pistol at them might have the same effect. So what makes smiling a signal rather than just a way to manipulate the gullible? It turns out that those who smile more convincingly are the ones whom it pays to trust: they really do return more money overall. And there's an interesting twist to this: they return more money not just because they do so more often but also because they have, on average, more money to return (so they have more to smile about). A smile is a reliable signal not just of a person who's more disposed to share their pie with you but also of a person who has a bigger pie to share. This result suggests that the ability to be charmed by a smile was not just some dangerous susceptibility for our ancestors but offered an adaptive advantage.

In our experiments, we've found, too, that the ability to smile convincingly doesn't just come as a package with a more generous disposition, something that either you have or you don't. When subjects play for larger stakes, they put more effort into their smiling, and it shows. (Think what happens when you have an important job interview: you put a lot of mental effort into developing the frame of mind in which you can behave charmingly to your interviewer.) In short, it's difficult to smile convincingly if you don't have a reason to do it. As with most difficult activities, people make a bigger effort to smile if they see a larger gain from doing so. And natural selection seems to have rewarded them for that effort, since those who make the effort get better results than those who don't.

The nineteenth-century French psychologist Guillaume Duchenne using electrical stimulation to induce artificial smiles, thereby demonstrating that “genuine” smiles use more than the muscles around the mouth. © Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis.

Like other kinds of signaling, then, smiling has evolved as a way for people to decide (faster than if they had to work it out explicitly) whom they can afford to trust. Smiling plays an important part in sexual flirtation, but, like so much else about sex, it's also part of a much bigger story about human cooperation at all levels. Cooperation requires choosing partners. Competing against others to be chosen by the most desirable partners stimulates advertising. In a species as cooperative as our own, advertising is everywhere: in every gesture, every movement, every utterance. To succeed, it's essential to stand out somehow, and standing out often requires being different from the background. That helps us to understand the origins of the astonishing variety of human cultural behavior.

A World Saturated with Advertising

Some advertising tries to be attractive to everyone, trumpeting generally valued attributes like reliability or value for money. But often it signals particular qualities that only some people care about: design, taste, or style. This kind of advertising is not necessarily less cost-effective: it concentrates on a smaller audience to make its pitch more intensely. Sexual signaling is no less protean in its purposes: some of it is about advertising qualities that most people would find attractive in a mate: health, wealth, or intelligence, for instance. One theory of the evolution of the peacock's tail suggests that it advertises the superb fitness of its bearer because only a really fit peacock could possibly get away with the ridiculous metabolic expense of growing such an absurd appendage and bearing the insane handicap it imposes on its chances of escaping predators (this is known as the “handicap” principle).17 As with the Claudia Schiffer car advertisement, or the bread and circuses of the Roman emperors, the expense of the display is—according to this theory—not an incidental cost but the whole point. Of course, it's not the handicap in itself that is attractive: it's the underlying high quality of the signaler, who, by showing that in the presence of the handicap he can do at least as well as this rivals, inspires the belief that the underlying quality more than outweighs the handicap.18 And the handicap may not have been at the origin of the display's attractiveness: the first peacocks' tails may have been eye-catching enough to appeal to an existing sensitivity to bright colors on the part of females, and it may only have been once they grew substantially that the handicap began to count.

Other kinds of advertising signal “niche” qualities that only some audiences find attractive: while (almost) everyone might prefer an intelligent mate, not everyone prefers an intellectual one. Height in a partner might be a sign of health, but it's attractive only up to a point: taller people usually prefer taller mates, and shorter people prefer shorter ones. So an alternative theory to explain the evolution of the peacock's tail is that it started out not as a signal of greater fitness but as a niche taste. Large, bright tails simply appealed to the kinds of female that preferred large, bright tails.* Once such females were around in sufficient numbers, their taste itself became adaptive because females who shared it would have male offspring that would appeal to other similarly inclined females. This is known as the “sexy son” hypothesis,19 and it's not incompatible with the handicap principle: peacocks' tails might have arisen from both advantages. There has been independent confirmation of this suggestion from experiments showing that female birds who are initially indifferent to a particular male may become attracted to him suddenly if they observe him apparently surrounded by other admiring females.20 You can confirm this tendency yourself in the species Homo sapiens: in public spaces such as trains, airports, and restaurants, both men and women go to great trouble to signal, through ostentatious use of their smartphones, just how popular they are: they clearly believe this stimulates interest in them rather than discourages it, and they seem afraid of being thought of as losers if their mobile devices are not continually chirping and bleeping.21 The fact that it's a relatively low-cost strategy means, of course, that it's likely to be heavily overused.

Charles Darwin, who developed the theory of sexual selection in his book The Descent of Man, was the first scientist to realize that specialized advertising could explain rapid, divergent evolution in the characteristics of closely related populations.22 It's striking how different from each other many closely related bird species look, such as different species of bowerbirds or birds of paradise. The reason is almost certainly that the parent species clustered into subpopulations according to the tastes of the females who were selecting between types of masculine display. The females with one niche taste bred with one group of males, while those with a different niche taste bred with a different group of males. The resultant reproductive isolation—due to the females' choice, not to geographical separation— led the subpopulations to diverge rapidly into distinct species. What stops Homo sapiens from likewise separating into subspecies based on, say, tastes in rock bands is the fortunate fact that most children never inherit their parents' taste in music.

Darwin was also aware that on even shorter timescales, sexual selection might lead to striking variations in superficial characteristics between otherwise very similar subpopulations of the same species. This observation had an important application to human society, where there are conspicuous differences in hair and skin types across geographical regions. Darwin realized that if sexual selection could explain why human populations from different continents could look so different when, as he believed, they were so closely related to each other, there would be an important political as well as a scientific implication. Adrian Desmond and James Moore have argued that Darwin was strongly motivated by his detestation of the institution of slavery, which he had seen at close hand during the voyage of the Beagle.23 He reacted in particular against those defenders of slavery who argued that the black races were a different species from the white races. Darwin hoped that if it could be shown that all the human races were descended from a single human ancestor, the case for mistreating the members of what he called the savage races would be much weaker. In order to do that, he had to explain why the black races and the white races and the brown races looked so different when they were really so similar. Sexual selection came to be crucial to that explanation: the fact that dark people might prefer on average to mate with dark people, tall people with tall people, and so on could lead to rapid divergence in the superficial and visible characteristics of human populations even if their more fundamental characteristics remained very similar.

It's worth emphasizing the importance of Darwin's theory of sexual selection for explaining human diversity, because substantially divergent evolution between closely related populations is surprising unless those populations are physically isolated (like the Galápagos finches on different islands). Not only do most closely related species show strong resemblance, but it is striking how often natural selection has even produced convergent evolution: that is, it has found functionally similar solutions to the same problem on multiple occasions. Thus birds and bats have both evolved wings. Arctic and Antarctic fishes have both evolved a way of stopping their blood from freezing in the cold waters by synthesizing antifreeze proteins, but they do so using different proteins and with quite different genes that encode for them.24 Anteaters in Australia and South America have developed long snouts, but they are not at all related, and their common ancestor almost certainly didn't have such a snout.25 The gene for lysozyme, an enzyme that is part of the immune system, has evolved convergently in different cellulose-digesting mammals.26 Garter snakes and clams have independently evolved a very similar mechanism that gives them resistance to toxins in their prey.27

So there are several examples in which natural selection in a reasonably static environment has implemented the same functional solution to a problem in two or more different anatomical ways. Sexual selection, in contrast, is about the coevolution of the characteristics of an individual with those of somebody else, a mate or a rival: as the behavior of the mate or the rival changes, so does the way in which it's best for the individual to respond. Sexual selection is trying to hit a moving target, and two closely related populations can move the target in quite different directions. Again and again we see examples of divergent evolution between closely related species, in spite of their similar habitats and similar histories.

This coevolution is also the source of sexual conflict, which, as we saw in chapter 1, occurs even over when and how to mate: each modification in the strategy of males poses a new challenge to females, and vice versa. It underlines something about the often strikingly wasteful character of sexual selection. There is wasteful advertising: wouldn't it be easier if peacocks found a simpler way to signal their fitness? There is wasteful investment in male strategies to subdue females and female strategies to escape persistent males. There is wasteful competition between rival males, which takes all forms from the battles of dominant sea lions to the slaughter of young men in military campaigns (this doesn't mean that any individual male is behaving irrationally, just that competition makes all collectively worse off). Darwin himself famously wrote, “What a book a devil's chaplain might write about the clumsy, wasteful, blundering, low and horribly cruel work of nature.”28 For people who have seen how admiringly Darwin wrote about the beehive and about some of the perfectly formed organs of the animal body, it can sometimes be a surprise that he was completely aware of the more rebarbative results of evolution by natural selection. But he was as lucid about the horrors of the natural world as he was enchanted by the beauties of its design.

Advertising and Enchantment

Many of the achievements of our civilization started out as ways for men and women to impress each other. Whether you call them wasteful depends on your perspective. The cosmetics industry is in some sense a vast waste of money: if the purpose of cosmetics is signaling, why don't we all just get DNA tests to signal our genetic qualities directly? The answer is that even if signaling may be the reason why cosmetics increase someone's sex appeal, natural selection has shaped us to respond to the signal and not to the underlying reason. Characteristics that seem sexy in a potential partner don't become less sexy when we reflect that they originally attracted our ancestors because they signaled something else, such as fertility. The knowledge that someone is vasectomized or on the pill need not diminish their sex appeal one bit. Conversely, a certificate of your DNA profile will not evolve to look sexy on less than a geological timescale, which is longer than most people are prepared to wait to find a sexual partner.

Competitive sports are also a form of signaling. Inciting young men to compete to kick footballs through goalposts sounds like the most fatuously wasteful occupation ever invented, yet the delight it brings to the millions of spectators around the world suggests that “waste” is never quite what it seems. And this is as true of “high” culture as of the mass-market kind; poetry and song both started out as instruments of display, whatever elaborate reasons we may give for their effect on us now. When Shakespeare writes that “love is not love / Which alters when it alteration finds,” his readers should not be fooled. He may be writing a sonnet, but he is not engaging in careful factual description of people's feelings. He is not commending a psychological hypothesis—certainly not one so overwhelmingly at odds with the evidence accumulated over centuries. He is not developing an objective thesis on the human condition out of a wish to advance our knowledge or the search for the Platonic form of beauty. He (or at least his narrator) is signaling: pleading to be taken seriously, pleading all the more urgently because deep down he has doubts about his own constancy too.29

The enchantment woven by love is no less real for being elusive and ineffable: its elusive and ineffable nature serves powerful biological needs precisely because it bypasses the explicit reasoning of the calculating brain. Indeed, the reluctance we sometimes feel to look too closely at the hidden sources of that enchantment is exactly what you'd expect a sophisticated process of advertising to encourage. Manufacturers of perfumes never show you the pipes and pumps in their factories, and most upmarket restaurants would never allow the diners anywhere near the kitchen. I once saw a sign on a small furniture store in east London that read: “We buy junk and sell antiques.”* It was funny not because it was false but because it was a truth other stores would never acknowledge, just as in politics, according to the journalist Michael Kinsley, “a gaffe is when someone accidentally tells the truth.”30 The vendors of some of the most potent sexual attractors of all, cut diamonds, go to enormous lengths to disguise the fact that they are basically buyers of pebbles and sellers of dreams. The alchemy by which the former are transformed into the latter is less charming the more you know about it. As their customers, we don't necessarily want to know any better: if an engaged couple really believes that the exchange of one type of pebble gives their relationship more staying power than another type of pebble, only a very heartless observer would want to disabuse them. “Know thyself,” said the inscription in the temple of Apollo at Delphi, but it is a counsel of perfection, and perfection can be the enemy of the good. If you've been given the placebo in the randomized double-blind trial of a drug that could save your life, you'd rather never know.

If we sometimes have good reasons for not trying too hard to untangle the deceptions practiced on us by others, at other times even active self-deception may be in our interests. The biologist Robert Trivers has suggested that self-deception may be a natural by-product of features of brain organization that help us deceive others. It's easier to hide from others evidence that is inconsistent with what you say if you also keep that evidence out of your own conscious mind, whose processes are more visible to the outside world. Some recent experimental evidence supports this theory, suggesting that various self-serving biases in people's beliefs tend to weaken when their attention is given a heavy cognitive load to process.31 This finding pushes to its logical conclusion a quite reasonable preference we all have at times for what might be called minimal communication under stress: sometimes you'd rather have an uncomfortable discussion over the telephone or by e-mail rather than in person, because it reduces the effort you have to invest in mastering your feelings and trying not to reveal too much. Self-deception is the most minimal communication of all, because you hide from your own conscious awareness the things it would be costly to reveal to others, things it would cost you continued effort to suppress if you acknowledged them.32

Indeed, self-deception flourishes in precisely the areas of life where these costs matter most: in business, in politics, and in love. The most effective salespeople are often those who really love their product, whatever natural tastes they may have had to suppress to reach this state. Many politicians, whose every utterance is scrutinized for the consistency of its logic and body language, find it easier to persuade themselves of the truth of various conveniently self-serving beliefs before they start to promote them to others. That's why it may not always make sense to ask whether a politician is lying or is sincere: the answer may be “Both.” The nineteenth-century British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli memorably captured the attractions of this strategy when he described his opponent William Gladstone as “a sophistical rhetorician, inebriated with the exuberance of his own verbosity.” Disraeli's pairing of the characteristics of sophistry and inebriation is at first surprising—you'd expect the latter to make the former impossible— but as the logic of self-deception has shown, it's absolutely accurate. And any lover will be more ardently convincing if he has already silenced whatever internal doubts he may have about the extravagance of his declarations. Before deciding whether to propose marriage to someone, you should read everything you can find about divorce statistics, but once you've decided to go ahead and make the proposal, you should forget everything you've read.

In short, there are good reasons for our reluctance to dwell too closely on the underlying biology of our emotional commitments: natural selection has made us that way because the commitments are more effective when we and our partners lack the lucidity to unravel their origins.* But these reasons, persuasive as they are, don't make the biology go away. Love can weave enchantment that, like all magic, fosters in the enchanted the illusion that the present moment is inexplicable and ineffable, beyond all purpose outside itself. To a person in love, the irreplaceability of the loved one is unarguable and its origins in our endocrine system an irrelevance. To those whose lovers have left them, the memory of abandonment, even years later, can be evoked by the cadence of a forgotten voice, by a half-caught aroma of jasmine or by a whisper of silk. Even so insubstantial a reminder can leave them emotionally sandbagged, in a state that language seems wholly inadequate to describe.33 We often don't even want to understand why we feel that way: we fear that understanding would leave us forever unable to succumb to enchantment again.

Nevertheless, once we ask ourselves the question, we should be lucid about the answer: if we are susceptible to enchantment, natural selection has had its reasons for making us so. When John Donne writes of the passion that makes “one little room an everywhere,” or Jacques Brel sings of a love that drapes in beauty the ugliness of the suburbs, inviting the enchanted to admire, it is because the act of doing so makes the enchanted stand still. If you can make a man think one room is everywhere—especially a man with as much testosterone as John Donne—you dampen his urge to wander elsewhere. The very lives of your children may depend upon it.

Both the magic and the menace of sexual love have become so elaborate in the human species because cooperation is central to our social life, and because making children and preparing them for life demands a degree of long-term commitment surpassing anything else seen in nature. It's a commitment that sets up unprecedented tensions between the long-term and the short-term interests of the partners and complicates dramatically the nature of the signaling between them. In chapter 4 we look at why and how our ancestors came to develop that particular model of social behavior, which took us in a very different direction from the other social primates who are our closest natural cousins. It meant that our capacity for sustained teamwork had a much larger influence on our survival and reproduction than it has done for any other mammals (social insects such as ants, bees, and termites are great cooperators too, but males play a much smaller part in the team, and these insects' sex life has little to make us envy them).

You might think that our massive dependence on sustained teamwork would have led to strong selective pressures to make us nicer or more dependable. There's an element of truth in that: when successful and sustained teamwork matters, natural selection may favor qualities such as generosity and loyalty. But it may also, and simultaneously, favor the talent for manipulating others, for benefiting from the contribution of others while minimizing your own. Above all, it has favored the talent for subjecting the behavior of others to the sharpest and the most unforgiving scrutiny. Enchantment and suspicion have entwined themselves together around the solid trunk of human social life.

The Birth of Suspicion

Suspicion is born out of the richness of the signals that human sexual partners send to each other and the ample opportunities they create for confusion and manipulation.34 Their behavior is a continuation in more elaborate form of a simple interaction that is everywhere in nature. To understand it, we need to examine what it shares with the behavior of other species as well as what makes it different. Vast and various though it may appear in the natural world, the range of strategies used by males to gain access to females amounts in the end to a series of elaborate variations on only two themes: defeating rival males through force or cunning, so that the victor has the choice of females to himself, and impressing the females so they choose him over rival males. If the victor has the choice of spoils, that's a setting that favors flamboyance and risk taking among the males. Aristocratic strategies will always thrust aside the prudent and bourgeois virtues: being good enough is never quite good enough. In this world, suspicion is a guy thing: males are each other's rivals and the objects of their most intense mutual scrutiny; females largely take what they can get. But even when persuasion rather than force is the weapon of choice, the only thing that impresses the females, in many of the species where they get to choose, is the quality of a male's sperm, which is all he will ever contribute to the partnership. However elaborate the signaling, it is always aimed at communicating that one attribute.

Given how cheap sperm is to produce, and how many females the most successful male can inseminate, this criterion of female choice creates a strong incentive to aim at being the very best; there's no reason why females should settle for second best, any more than music lovers should settle for listening to a second-best recording when the best is also available and can be easily reproduced. They have a strong incentive to scrutinize and select the males, but once the deal is done, there's no need for further vigilance.

But man cannot live by sperm alone, and nor can a good number of other species. A number of males offer food or protection along with their sperm. In some species—in the dance fly, for instance, and even more spectacularly in those species of cannibalistic spiders we met in chapter 1—the food and the sperm are delivered together. The male has an obvious interest in making sure the link between the two offerings is unbreakable: from natural selection's point of view, the investment of food is worth making only if it really is his sperm that fertilizes the female. In others—in many birds, for instance, as well as in human beings—the food and the sperm are not delivered simultaneously but can arrive in a series of interleaved deliveries over quite a long period. Because the female now has an interest in ensuring that these deliveries are really made as advertised, suspicion about the quality of the male's promises is now a natural and adaptive psychological trait. But suspicion goes both ways: the male's interest in ensuring that only his sperm gets to fertilize the female in whom he is investing his food remains un-diminished, and he can now no longer rely on simultaneous delivery to ensure that. This isn't just a matter of accident: natural selection sets the females' interests subtly in opposition to his own. Since the emergence of pair bonding, it has occurred to females of a number of species to wonder whether the two things—food and sperm—absolutely have to come as a package deal. Perhaps the food could come from one male and the sperm, or at least some of the sperm, from another.

To put it more accurately, it is natural selection that, by transmitting the restlessness in a woman's loins to her daughters and her granddaughters, has been doing the wondering for all of them. That restlessness first made itself felt many millions of years ago, but already the countdown to Anna Karenina had begun.*

*Carrying a camera can be dangerous in authoritarian countries, even in the most unexpected places: the fact that there are no military secrets worth photographing at a certain site may itself be a military secret.

*As this hypothesis indicates, scientists can launch successful careers on the enunciation of tautologies: the trick, obviously, is not to stop there.

*There's even a website called Webuyuglyhouses.com. In case you wonder what they sell, the answer seems to be “luvly” houses.

*Scientific hypotheses can be enchanting too: as Fernando Pessoa put it, “Newton's binomial is as beautiful as the Venus de Milo, but fewer people realize it” (Pessoa 1987, 238, my translation).

*Novels are notoriously unreliable as a source of evidence, since novelists are fascinated by the exceptional, but they can aptly express certain ideas that are amply corroborated from other sources. Stendhal, writing in 1830, has a sardonic description in which Julien Sorel imagines himself loving a sophisticated woman in Paris: “He loved with passion, and he was loved. If he left her for a few moments, it would be to cover himself with glory and to deserve her love all the more.” But Stendhal adds that any young man who had actually been “brought up among the sad realities of Parisian society would have been woken at this point in his novel by a cold irony, and his grand actions would have disappeared, along with any hope of achieving them, to be replaced by the wellknown maxim: leave your mistress's side and you'll be cuckolded—alas—two or three times a day” (Stendhal 1962, 68– 69). A century later, Joseph Keller wrote of his novel Belle de Jour (published in 1928 and later made by Luis Buñuel into a film starring Catherine Deneuve) that “what I tried to do was to show the terrible divorce between the heart and the flesh, between a true, vast and tender love and the implacable demands of the senses. With a few rare exceptions, every man and woman who loves for a long time bears this conflict within. It may be felt or not, it may slumber or it may tear, but it exists” (Keller 1928, 10, my translation).