ONE

From Marketing as a Function to Marketing as a Transformational Engine

Markets always change faster than marketing.

IN The Practice of Management, Peter Drucker wrote, “The business enterprise has two and only two basic functions: marketing and innovation. Marketing and innovation produce results; all the rest are costs.”1 Today, many CEOs of major companies are disappointed over marketing’s inability to produce measurable results. Increasingly, they view their marketing department as an expense rather than an investment, and fewer marketers are rising through the ranks to become CEOs. While companies unabashedly declare their wish to get closer to customers, marketing is actually losing power to other functions in the corporation.

What happened? How did marketers lose their influence, and marketing its organizational relevance? More important, how can marketers capture the imagination of CEOs and marketing recapture its strategic role in the firm? Ironically, while the marketing function has been declining, the need for marketing has never been greater. However, to rescue themselves from the corporate obscurity that comes from responsibility for implementing tactics—the traditional four Ps of product, place, price, and promotion—marketers must start driving overall strategic change. They must help CEOs lead organization-wide transformational initiatives that deliver substantial revenue growth and increased profitability.

The Decline of Marketing

After the postwar 1950s boom, marketing quickly rose to power. Customers were trusting and abundant, distribution channels were fragmented and weak, new product launches were less frequent and more substantial, and prices were under little pressure.2 In such an environment, mass media, especially network television, was a powerful tool for reaching large numbers of homogeneous consumers. Marketing led both top- and bottom-line growth for companies.

Over the past two decades, marketing as the company’s growth engine has sputtered amid increased market fragmentation, strong global competitors, product commoditization, increasingly shorter product life cycles, skyrocketing customer expectations, and powerful channel members. As a result, the ability of marketing to deliver significant growth has been severely constrained and marketing productivity has declined. Not surprisingly, in many companies, doubts have begun to surface about the value of contemporary marketing.3

A study of 545 U.K. companies revealed that just 18 percent of executives rated marketing’s strategic effectiveness in their company as better than good while 36 percent rated it as fair to poor.4 Another study of senior executives indicated considerable dissatisfaction with the marketing skills of brand managers (overall effectiveness, 48 percent; strategic skills, 60 percent; innovation, 92 percent; risk profile, 48 percent; and speed, 56 percent).5 Ambitious marketers are therefore finding it difficult to reach the CEO position.

A 2001 study of the FTSE 100 index firms in the United Kingdom revealed that just thirteen chief executives had marketing backgrounds compared with twenty-six who rose through finance.6 The study also found that the number of CEOs from marketing backgrounds had declined over the past three years. Furthermore, even in consumer goods companies that presumably value marketing efforts, accountants outnumbered marketers as CEOs.

British Airports Authority CEO Mike Hodgkinson argued that his accountancy training offers two advantages over someone with a pure marketing orientation. “I can speak the shareholders’ language and the training gave me a disciplined approach to issues.”7 Marketers are often not considered capable of getting the company through tough times with their “spend” rather than “make-and-save” mentality. It is no wonder that Niall FitzGerald, head of Unilever, describes himself as “an accountant by training, a marketer by instinct.”8

True, some companies have had unrealistic expectations of marketing given the more competitive landscape. Still, many CEOs, unable to count on their marketing departments for results, have had to turn instead to operations and finance, cutting costs and reengineering the supply chain to increase profitability and mergers and acquisitions to grow revenues. Consequently, marketing’s share of voice at the corporate level has declined. Research now demonstrates that, at large companies, only 10 percent of executive meeting time is devoted to marketing.9

As the attention and imagination of CEOs have shifted to other functions, marketing academics have bemoaned marketing’s declining influence within the firm. Don Lehman, the director of Marketing Science Institute, a leading academic research think tank devoted to marketing, recently observed: “Marketing as a function is in some danger of being marginalized.... Some think that marketing people do little more than blue-light specials and coupons.”10 Fred Webster, a noted marketing professor, argued that marketing has surrendered its strategic responsibilities to other functions that do not systematically prioritize the customer.11

Numerous conferences have been organized to help reinvigorate the discipline. To earn the respect of CEOs and CFOs, the established academic marketing interest groups have launched a campaign to document the importance of marketing by attempting to demonstrate the return on investment (ROI) from marketing expenditures. The feeling is that, consumed by a focus on shareholder value, CEOs and companies are unable to see the value of marketing. Therefore, in this line of reasoning, marketers must find metrics that will document the positive impact of their activities on shareholder value.

The search to demonstrate the ROI of marketing misses the point and reinforces the perception that marketers still misunderstand their CEO’s expectations. Of course, CEOs want to increase the efficiency of current marketing activities, namely the tactical four Ps. However, CEOs really seek strategic leadership from marketers in exploiting new business opportunities, building strong brand and customer franchises, increasing the organization’s overall customer responsiveness, redefining industry distribution channels, enhancing global effectiveness, and reducing such risks as industry price pressures. It is about marketers doing better things rather than simply doing things better.

Getting Marketing Back on the CEO’s Agenda

In an annual survey of CEOs conducted by The Conference Board, nearly seven hundred CEOs globally were polled about the challenges facing their companies in 2002.12 CEOs identified “customer loyalty and retention” as the leading management issue ahead of reducing costs, developing leaders, increasing innovation, and improving stock price, among other issues. In the same survey, “downward pressure on prices” emerged as the top marketplace issue, rated ahead of challenges such as industry consolidation, access to capital, and impact of the Internet.

This survey clearly reveals that CEOs already see their most important challenges as marketing ones—they just don’t believe that marketers themselves can confront them. The marketing function may have lost importance, but the importance of marketing as a mind-set is unquestioned in firms.

CEOs know that their firms must become more marketoriented, market-driven, or customer-focused. But a true market orientation does not mean becoming marketing-driven; it means that the entire company obsesses over creating value for the customer and views itself as a bundle of processes that profitably define, create, communicate, and deliver value to its target customers. Only demonstrated customer value can assure firms of fair, perhaps even premium, prices and customer loyalty.

The Ubiquity of Marketing Activities

If one believes that everyone in the organization should serve the customer and create customer value, then obviously everyone must do marketing regardless of function or department.13 In fact, most of the traditional activities under the control of marketing, such as market research, advertising, and promotions, are perhaps the least important elements in creating customer value.

The accounting department is marketing when it develops an invoice format that customers can actually understand. The finance department is marketing when it develops flexible payment options based on different customer segments. The human resources department is marketing when it involves frequent flyers in helping to select in-flight crew. The logistics team is marketing when it calls on a major customer to coordinate supply chains. The operations department is marketing when its receptionists smile at guests during hotel check-in. In all these activities, what role does the marketing department typically play? None. And so, substantial reductions in the size of marketing departments may be simultaneously associated with a greater number of marketing activities performed and a higher market orientation throughout the company.14

With the activity of marketing dispersed across the organization, marketing is not the sole responsibility of the marketing department. For example, new product development in the automobile industry requires coordination among marketing (by defining the important attributes), product development (by designing a car that satisfies customer needs), purchasing (by providing realistic cost-benefit trade-offs when developing cars), manufacturing (by actually making the car), and external suppliers (who increasingly must deliver preassembled subsystems, not merely raw materials or parts).15 But who coordinates the activities across all of these functions to deliver a consistent customer experience?

The Networked Organization

Three mutually reinforcing changes are enabling faster and more coherent coordination of the customer value-creating activities within organizations.16 First, companies are thinking in terms of processes rather than functions. Second, they are moving from hierarchies to teams. Finally, they are substituting partnerships for arms-length transactions with suppliers and distributors. The tightly specified, vertical, functional, divisional, and closed organization is slowly becoming relatively loose, horizontal, flexible, dynamic, and networked.17

Ultimately, a customer receives the outcome of several cross-functional processes. Cross-functional teams break down silos and enhance critical processes such as new product development, customer acquisition, and order fulfillment. In these teams, formal leadership resides with the appointed team leader, but informally, leadership passes among team members based on their expertise and the problem at hand. Such teams actually do much of the work of organizations today.18

Marketing in the Networked Organization

The evolving networked organization demands that functional specialists and country experts learn how to communicate with other functions and nationalities. Consequently, organizations are emphasizing integration over specialization.19 But traditionally, marketing has systematically prioritized specialization over generalization, rewarding its academics and practitioners alike for knowing more and more about less and less.20

Nowhere is this excessive specialization more apparent than at business schools. Academic research in marketing typically attacks irrelevant, esoteric problems with highly sophisticated methodologies. To distinguish themselves from the strategy area, they are plunging deeper into tactical implementation issues. Anyone who attends an academic marketing conference will observe numerous papers presented on “promotions,” a euphemism for “price cuts.” What should have been a “field of dreams” has turned into a “field of deals.” Whereas marketing departments continue to churn out thousands of marketing undergraduates who find jobs mostly in sales, they have little to say that interests CEOs.

In all its specializing, marketing has not aspired to lead major transformational projects that involve cross-functional, multinational teams sponsored by the CEO. Other functions have rallied around transforming initiatives such as Total Quality Management (TQM) and reengineering led by operations, Economic Value Added (EVA) and Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) guided by finance, and the Balanced Scorecard driven by accounting.21 What, if anything, can marketing do?

Marketing as a Transformational Engine

For marketers to capture the imagination of their CEOs, they must break from the tactical four Ps and associate instead with organization-wide transformational initiatives worthy of the CEO’s agenda. Only initiatives that are strategic, cross-functional, and bottom-line oriented will attract the CEO’s attention, and only by leading such initiatives will marketers elevate their role in the organization. Marketing must never limit its scope to implementation issues.22 It must aspire to participate in those conversations that shape the firm’s destiny.

Since CEOs can focus on only a few major initiatives at any given moment, they usually choose those that require improvement on multiple dimensions simultaneously—greater service, lower costs, improved quality, greater customization, and more focused communications.23 So marketers should target problems that involve multiple products, countries, brands, channels, and/or functions. True transformational leaders think across multiple dimensions and levels of abstraction.

A cross-functional orientation requires marketers to understand the entire value chain thoroughly, including engineering, purchasing, manufacturing, and logistics, as well as the enabling functions of finance and accounting—and not simply advertising, promotion, and pricing.24 When experienced marketers ask me which executive marketing program would improve their skills, I direct them to a course on finance or operations. Only by deeply understanding all other functions can marketers guide activities across the entire value chain. Transformational marketing efforts should focus on initiatives that

- profitably deliver value to customers;

- require a high level of marketing expertise;

- need cross-functional orchestration for successful implementation; and

- are results-oriented.

As professors Sheth and Sisodia observe, despite being several times greater than capital expenditures in many companies, sales and marketing expenses do not receive the same level of rigorous evaluation that capital expenses do.25 The belief is that a finance person managing a brand would probably take more time to determine how much to spend to support it and how to measure the effects of the spending than a marketer, who would just ask for more money.26 Today, shareholders great and small are pressuring corporations and their CEOs to deliver against short-term profit and revenue objectives while maintaining the overall strategic direction. Marketing initiatives must have a substantial, demonstrated, top- or bottom-line effect to excite the CEO. Any lag between a marketing activity and its effect should not excuse marketers from measuring those effects whenever possible. Faithbased marketing is no longer an option.

The CEO’s Marketing Manifesto

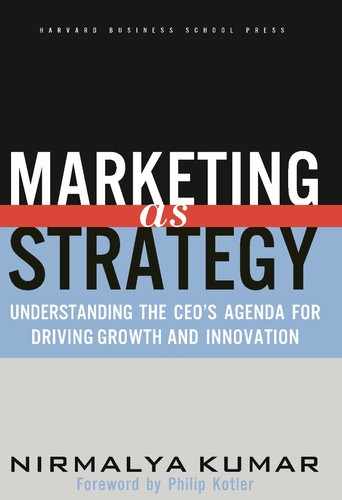

Figure 1-1 divides the CEO’s Marketing Manifesto into seven organization-wide transformational initiatives that marketers could lead. These initiatives pass the three tests outlined above: Each is strategic, cross-functional, and bottom-line oriented. While all seven transformations may not apply to all firms, at least one will apply to every firm. Current projects within a company may actually address one or two, in which case the respective chapter should help provide strategic and implementation tools. The firm may not have considered one of these initiatives before, and so this book will help managers to go beyond best practice to next practice.

The CEO’s Marketing Manifesto

From Market Segments to Strategic Segments

In the face of increasing price pressure and declining customer loyalty, more than anything what CEOs seek from marketing is differentiation, especially differentiation that is difficult for competitors to imitate. As Franklin D. Raines, chairman and CEO of Fannie Mae, observed: “People talk about mortgages as commodities. But . . . nothing has to be a commodity. Not even mortgages.... Indeed, our strategy is to transform mortgages from commodities.... We are not talking about mere branding, we mean creating real differentiation that consumers value.”27

Traditionally, marketing has relied on market segmentation and marketing mix to create differentiation. Market segmentation is the process of dividing the market into clusters of customers in such a way that each market segment is best reached through a unique marketing mix of the four Ps. However, creating differentiation across segments exclusively through the four Ps is too limiting. Instead, marketing needs a framework that inspires greater strategic insights, that examines the cross-functional implications of serving different segments of customers, and that allows an identification of where, deep in the organization, any differentiation is being created.

To meet this need, I propose the concept of strategic segments. To create meaningful differentiation through strategic segments requires dedicating unique value networks to serving individual strategic segments. A value network, sometimes also referred to as a value chain or business system, is the orchestration of all marketing and nonmarketing activities necessary to create value for the customer. Replicating a value network is more difficult than copying a marketing mix. Therefore, the concept of strategic segments helps identify opportunities for deep differentiation.

Chapter 2 will examine the transformation from market segments to strategic segments. Adopting the strategic segments framework will help marketing address CEO-level questions regarding segmentation such as, Can one organization serve two different segments? Where in the value network is differentiation necessary to serve the varied segments? When is differentiating on the four Ps enough? How can one distinguish between strategic segments versus market segments?

The segmentation dilemma at the CEO level is determining where in the value network the firm must build differentiation to effectively serve the different segments without losing the potential synergies of serving a portfolio of segments. If the value network segregation for the strategic segments is too shallow, then it will lead to customer dissatisfaction. On the other hand, too deep a segregation in the value network may destroy opportunities for economies of scale.

From Selling Products to Providing Solutions

In a global marketplace, customers are awash in supplier choices, and differentiation based on products is usually unsustainable. For example, Gillette spent almost a billion dollars and seven years to develop the triple-blade Mach 3 razor. The U.K. retailer Asda needed only two months to copy it. Given relatively undifferentiated products, consumers will pay more only for demonstrated value. CEOs want their companies to enhance customer loyalty and alleviate pricing pressures by offering customers solutions instead of products.

After attending presentations by the CEOs of Sun Microsystems, AMD, Microsoft, and others at COMDEX (the most prestigious trade exhibition in the technology world), a reporter observed that any of those CEOs could have uttered the following line from Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina’s keynote: “The latest and greatest [is] . . . not what you need most.... While point products are cool, what you need most are solutions . . . a partner who can help make all the pieces you’ve already got work better together, who can manage your systems seamlessly across global networks.” 28 Imagine that, from an industry famous for falling in love with its gizmos.

The traditional marketing technique of simply offering another standard product under a “brand name” is currently inadequate to lock in customers. Today, customers are time starved, impatient, and demanding. They presume product quality and demand solutions, personalization, meaningful choice, and easy-to-do-business-with companies. Companies as diverse as Baxter International, W.W. Grainger, Home Depot, and IBM have recognized these demands. For example, Home Depot’s research indicates that traditional “Do-It-Yourselfers” are evolving into “Do-It-For-Mes.” As a result, Home Depot is intensifying service and training personnel to ask potential shoppers, “What project are you working on?” rather than “What product are you looking for?”

Chapter 3 will study the transformation necessary within organizations that desire to move from selling products to providing solutions for customers. Solution selling creates many challenges that tend to land on the CEO’s desk. How can we move the company’s mind-set from developing “better” products to solving customer problems? How can we obtain company-wide coordination from the different parts of the organization that have traditionally competed against each other? How can we assess the value of solutions for customers, and then subsequently price such solutions?

Firms aspiring to provide solutions encounter challenging dilemmas in creating true customer solutions and maintaining profitability. At some stage, solution-selling firms have to confront the reality that impartially serving customer needs may sometimes demand incorporating competitors’ products and services into the solution. In addition, delivering solutions entails significant additional customization costs for the seller, while many solution customers believe they are entitled to volume discounts.

From Declining to Growing Distribution Channels

Distribution channels today are in flux. Many traditional channels are declining and innovative new ones are emerging. Dell in the personal computer industry and First Direct in the insurance industry have seized market leadership by adopting direct distribution strategies. In contrast, Charles Schwab developed the financial supermarket, concentrating on distribution in a traditionally vertically integrated industry. By offering a vast selection of mutual funds from a variety of suppliers, Schwab more effectively serves self-sufficient investors.

The Internet’s rapid development has accelerated the number and diversity of distribution channels by introducing concepts such as Amazon, eBay, ebookers.com, FreeMarkets, Kazaa, NCsoft’s Lineage, and priceline.com. Most of these new online and offline channels are technology intensive and their competitive advantage over existing channels usually involves superior efficiency and greater reach. In some extreme cases, such as music, the efficiency and reach of online distribution has disrupted the entire industry’s business model.

Traditionally, industries such as automobile and financial services as well as companies such as Caterpillar, Delta, and Compaq have stressed their loyalty to existing channels and have opposed changing their distribution structure. For example, consider the automobile industry, where products have changed dramatically over the past hundred years but distribution has remained essentially untouched. Furthermore, like many existing distribution networks, automobile dealers are protected by tight contracts.

Demands from CEOs for revenue growth combined with the greater efficiency and reach of new distribution formats make it impossible for companies to ignore these emerging high-growth channels. For example, even Levi’s, who has long spurned the advances of mass merchandisers such as Wal-Mart or Tesco and sued them for selling its jeans at discount prices, has decided that it can no longer ignore them. It is introducing a new line of jeans targeted specifically at such supermarkets and mass merchandisers.

Chapter 4 examines the challenge of transforming traditional distribution networks and positioning oneself in the growing channels of the future. Since distribution structure decisions are relatively long term and have legal ramifications, channel migration requires firms to confront a number of issues that pique CEO interest. Should the firm be an early entrant or a fast follower into new channels of distribution? How can it migrate into new distribution channels while managing existing ones? How can the firm manage the ensuing channel conflict? Which industry players are best positioned to exploit new channel opportunities?

New distribution channels present a dilemma for a company. During the transition period, despite the rapid growth in new channels, existing channels still account for the lion’s share of the industry and the company’s revenues. Moving too fast into the new distribution formats can unleash destructive channel conflict. On the other hand, hesitancy can lock companies into declining distribution channels and high distribution costs. Players in industries as diverse as entertainment, financial services, personal computers, and travel are still struggling to strike the right balance.

From Branded Bulldozers to Global Distribution Partners

Beyond new distribution formats, existing distribution channels have consolidated and become increasingly sophisticated. FMCG companies, including the most famous household names, have been taken aback by the dramatic reversal in their fortunes due to the retailers.29 Historically, retailers were local, fragmented, and technologically primitive, and as such, powerful multinational manufacturers such as Coca-Cola, Colgate-Palmolive, Gillette, and Procter & Gamble behaved like branded bulldozers, freely pushing their products and promotion plans onto retailers, who were expected to accept them subserviently.

Within a span of two decades, all this has become history. The largest retailers, such as Carrefour of France, METRO of Germany, Tesco of the United Kingdom, and Wal-Mart of the United States, have global footprints. The worldwide revenues of these retailers exceed those of the large branded manufacturers and the retail industry is still in the early consolidation stage. As retailers have bulked up, they have moved from a position of vulnerability to one of power relative to their suppliers. This shift in power and the global purchasing practices of retailers has brought enormous price pressure on the most sophisticated of all marketers—the leading consumer packaged goods manufacturers.

The brand management system that worked so well in the past seems ineffective in dealing with large, professionally managed retailers. The typical brand manager is too inexperienced, too narrowly focused on the brand, and too short-term oriented, as well as lacking the internal authority and resources to be a strategic partner with the purchasing counterpart at a global retailer. In response, companies have been forced to introduce category management (combining the management of all brands within a particular category to ensure greater coherence in strategy) and customer development teams (bringing together representatives from different brands, categories, functions, and countries to present a single face to a retailer). Unfortunately all of these changes have not helped the perception of CEOs that marketing departments are bloated with much duplication of functions at the brand, category, country, customer, and corporate levels.

Chapter 5 investigates the necessary organizational and cultural transformation of manufacturers as they move from being branded bulldozers to global distribution partners with powerful distributors. The volume sold through global retailers demands CEO participation in these partnerships. For example, Wal-Mart alone accounts for more than 17 percent of Procter & Gamble’s worldwide turnover. Developing global manufacturer–distributor partnerships raises many issues including how to generate trust, how to manage global retailer demands, and how to develop global account management structures that provide an efficient and an effective interface.

The global account management dilemma for manufacturers is that prices for their nearly identical products can differ by as much as 40 to 60 percent between countries. Global distribution partners make such manufacturer products and prices “naked” by demanding a single worldwide price. Unfortunately, for most manufacturing companies operating in numerous local markets, customer ignorance was their biggest profit center!30

From Brand Acquisitions to Brand Rationalization

Powerful distributors are using their tremendous negotiating clout against suppliers to aggressively push them into granting trade promotions, slotting allowances, and failure fees, besides, of course, the usual price concessions. As a result, marketers have increasingly diverted resources to various forms of promotions to move volume. In 1997, the percentage of total sales volume for select items in U.S. supermarkets that sold on promotions was 35 percent for fresh bread, 36 percent for diapers, and 62 percent for refrigerated orange juice. Similarly, marked-down products that accounted for just 8 percent of department store sales three decades ago have now climbed to about 20 percent.31

Even consumer durables and emotional products are not exempt. For example, for the big three U.S. automakers, incentives now amount to $3,764 per vehicle or 14 percent of the selling price of a vehicle.32 Without strong brands and competitive products, even short-term promotions may backfire, as happened in the fall of 2001 when the big three automakers furiously launched zero percent interest financing to draw American customers into their showrooms. It turned out that the customers came into the showroom, compared cars, and disproportionately bought Toyotas and Hondas even though these Japanese companies were not offering similar low interest rates. No wonder Chrysler CEO Dieter Zetsche, who is trying to wean Chrysler away from incentives, observed: “I see it as a drug. It might give you short-term relief, but long term it is extremely harmful.”33

CEOs are questioning why marketing efforts are being allocated primarily to short-term sales inducements rather than long-term investments in building brand equity. Why has distribution pushback onto manufacturers been so successful in obtaining price concessions? To a large extent the answer lies in mushrooming brands. Companies like Akzo Nobel, Electrolux, General Motors, Goodyear, and Unilever have until recently had too many brands in their portfolios, most of them obtained through acquisitions over the years. While each portfolio contains strong global brands, a significant number of the brands are both weak and local.

Distributors and retailers excel at playing weak manufacturer brands against each other and holding name-brands hostage. CEOs are demanding that marketers brutally examine the brand portfolio, and then delete, merge, or sell weaker brands to concentrate on the few truly differentiated brands.

Chapter 6 examines the transformation in brand portfolio strategy, moving from brand acquisitions to brand rationalization. How does a company decide which brands to delete? What is the role of each brand in the portfolio? How can brands be consolidated? Where in the organization should the locus of decision making for each brand reside?

The dilemma of brand rationalization is how to delete marginal brands without losing their associated customers and sales. Successful brand rationalization entails shrinking the brand portfolio while growing sales and profitability through greater focus on the remaining brands.

From Market-Driven to Market-Driving

At the top of every CEO’s agenda is growth through innovation. CEOs understand that, without innovation, companies risk their future growth and profitability, and so they devote considerable resources to launching new products. An estimated thirty thousand new products were launched in the U.S. last year in the packaged goods industry alone. Despite the $20 to $50 million average cost of a product launch, approximately 90 percent of new products fail.

Sadly, most of these launches involve incremental innovations such as new product lines for the company, line extensions such as new flavors, or improvements to existing products. Less than 10 percent of all new products are truly innovative or “new to the world.” Not surprisingly, between 50 and 80 percent of consumers in the United States and Western Europe believe that, in the past two years, no one has made any valuable innovation in many product categories (for example, housing, clothing, furniture) and service categories (for example, insurance, hospitals, education, government).34

Marketers unfortunately make two errors in pursuing the CEO’s innovation agenda. First, marketers tend to interpret innovation narrowly as simply new product development. Second, most marketers believe that new product development starts with consumer research, but this market-driven approach usually results in incremental product innovation rather than truly breakthrough business concepts.

CEOs are insisting that their organization think of innovation beyond new products, services, or even processes. More specifically, their mandate is to generate radical market-driving concepts, such as NTT DoCoMo’s i-mode, Sony’s PlayStation, Nestlé’s Nespresso, and Zara’s catwalk fashions at cheap prices—products that change an industry’s rules and boundaries. 3M is often a poster child of the incumbent that creates new customer needs through market-driving innovations (Post-it notes) rather than by satisfying expressed market-driven desires.

Chapter 7 explores the transformation from market-driven to market-driving. It asks questions essential to the CEO’s agenda of changing an industry through innovation. What processes encourage radical innovation? What marketing strategies do we need for market-driving innovations? How do we manage simultaneous incremental and radical innovation?

The dilemma with market driving is to strike the proper balance between satisfying current customer needs better through market-driven processes and creating new market demand through market-driving processes while not being too far ahead of customers.

From SBU Marketing to Corporate Marketing

Consistent with marketing’s historical focus on the tactical four Ps, in most organizations marketing has been consigned to the strategic business unit (SBU) level. Rather than being a partner for the CEO in developing strategy content, marketing’s role is being increasingly subjugated into responsibility for short-term demand stimulation.35 Therefore, few companies exist where the corporate marketing function or role is substantial.

Currently, many CEOs believe that marketing is failing at the strategic level because marketing efforts are not aligned with the strategic goals and overall strategy of the firm. In the face of pressure to perform and demonstrate results, as with many complex challenges, managers are frequently in search of quick fixes. Rather than build long-term value for consumers and enhance the company’s success formula, marketers try to raise market share and sales through dubious temporary tactics such as more promotions, greater salesperson effort, and pushing inventory onto distributors. It is a short-term, paint-by-numbers approach.36

Marketing’s lack of productivity is often blamed on overutilization of short-term tactics and an overemphasis on customer acquisition and market share gains, while paying inadequate consideration to the profitability of the customers acquired or shares gained. Moreover, CEOs are uncertain even about the marketing gains. As one CEO of a food ingredient company remarked to me: “We spend all this money on marketing and what do we have to show for it? Perhaps I would be happy if at least we were competing on price but now we are competing on costs.”

CEOs want marketing to become a strategic partner, and many companies appoint chief marketing officers (CMOs) because SBU-level marketers usually lack the clout needed to lead when organization-wide marketing transformations cut across several SBUs. Transforming efforts such as brand portfolio rationalization, radical market concept innovation, solution selling, or global distribution partnerships require corporate marketing as the engine.

Chapter 8 examines the transformation from SBU marketing to corporate marketing. It answers such questions as, How can marketing create value from the corporate center? What is the role of corporate marketing? What initiatives should the CMO sponsor? What opportunities for marketing synergies and leverage exist?

The dilemma for corporate marketing is the belief in many companies that all marketing is local. Marketers must demonstrate that they can create value from the corporate center and partner with the CEO while balancing the legitimate local interests of SBUs.

Cultivating Organizational Respect for the Customer

CEOs are not alone in their frustration. Behind closed doors, marketers will likely complain that their CEOs do not understand the marketing function and do not sufficiently engage in the sales and marketing processes;37 or that others see them as a big cost center, a means of keeping up with the competition;38 or that marketing is like a charity: well funded in good times but the first to be cut in the bad.39

Many marketers feel that CEOs have unrealistic expectations about what marketing can do and do not sufficiently elicit marketing’s input into corporate strategy. Promotions—that is, price cuts—often proliferate because marketing must sell whatever the factory produces. This is common in the automobile industry. The leadership at Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors has not addressed fundamental issues such as surplus manufacturing capacity, overlapping brands, and product differentiation. Without built-to-order systems, tension thickens between car salespeople who have to move current stock, and consumers who want exactly what they can imagine—not what stands on the showroom floor.

Some CEOs erroneously believe that hiring world-class marketers from other companies will turn their company into a market-driven one but they cannot simply graft marketing expertise into an organization that is not already market-oriented.40 Companies like Unilever and Nestlé have great marketers on staff, but their marketing succeeds because the whole company, including the CEO, focuses on customers.

CEOs Leading from the Front, Rather than the Top

Unfortunately, CEOs often lose touch with their customers. One CEO of a major car company had never bought a car at a dealership and therefore could not understand customer frustration. Contrast that with Henry Ford’s sensibility: “When one of my cars breaks down I know I am to blame.”41

To appreciate the customer experience, CEOs and top management must learn to lead from the front rather than from the top. At Southwest Airlines, senior executives must spend time regularly in customer contact areas to interact with and witness other employees’ interaction with customers. Stelios Haji-Ioannou, CEO of easyJet, frequently flies in his economy class–only planes. Top executives at Sony tried to set up their own VCRs using the accompanying instruction booklet. This exercise led to the development of an easier menu-based application. While one CEO of a chemical company frequently logs customer complaints against his own company to assess responsiveness, how many other CEOs can even find the customer service numbers for their products?

The CEO should be the customer champion, a quality controller who regularly tests the systems. Symbolic gestures communicate this role most effectively to employees. For example, if an executive of Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group observes a full ashtray while awaiting an elevator, he will empty it. On full flights, Cathay Pacific bumps its board members to provide seats to paying customers. At one point, different offices competed to see who could bump the most board members, thereby demonstrating their customer orientation.

Beware of Make-Believe Marketing Metrics

To get respect, some marketers have rushed to quantify each activity in terms of profitability and shareholder value. After all, what cannot be measured, cannot be managed, let alone add value, right? Yet, we must avoid make-believe metrics.42 We can more easily measure the effects of promotions on sales and profits than those of advertisements, but that does not mean that we should rely more on promotions. Coca-Cola would not be a globally recognized brand today without a century’s worth of advertising.

Everyone in the organization, including marketers, must be bottom-line oriented. If profits fall short, then the company cannot continue serving customers or attracting resources to serve even more customers. While sales and profits tell us how well the firm has performed in the past, we must add indicators—marketing metrics like brand equity, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty—that inform us about the company’s current health and its prospects.43 The CEO plays an important balancing role. Robert E. Riley of Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group notes, “As managing director, I take ultimate responsibility for the brand—as any CEO must.... In every organization, ultimately the CEO must decide on the final balance between short-term financial objectives and the requirement to build the brand with a long-term perspective.”44

By building and using metrics that matter, one can clearly connect investments in marketing to the ultimate goal of satisfying customers profitably. These marketing metrics should help address important questions about the company’s marketing effectiveness, such as: Are we servicing our customers better? Have we truly differentiated our products in a clearly visible way that matters to customers? Is our differentiation generating profits for us? Does our price premium reflect the additional value delivered to customers? Are we satisfying our customers better than our competitors? Are we exploiting market opportunities faster than others? Do our people understand how we create value for our customers? Must distributors carry our products to maintain legitimacy in the industry? These questions will help a firm understand how well marketing is performing.

Unfortunately, the executive suite usually fails to ask them. Most boards of directors devote precious little time to such marketing- and strategy-related questions and focus instead on past financial performance and proposed budgets, of which the latter rarely materialize. On the boards that I sit on, I have always argued that we should carefully review marketing metrics such as customer satisfaction, brand equity, and customer loyalty. Let us bring the customer into the boardroom.

Discovering Consumer Capitalism

The dot-com bust and the failures of Enron, Tyco, and Worldcom have helped to shift the organizational arena in ways that will potentially benefit marketing and the customer point of view. Real customer value creation—not share price driven—strategies are back in vogue. After the financial engineering of the late 1990s, companies will do well by rediscovering the purpose of the corporation conceived in the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1954, Peter Drucker noted that the customer determines what a business is and is the foundation of a business.45 A Harvard Business School professor, Ted Levitt, argued persuasively that the “purpose of a business is to create and keep a customer.” 46 Profit, he contended, was a meaningless statement of corporate purpose. Without a clear view of customers, and how to serve them effectively, there could be no profits.

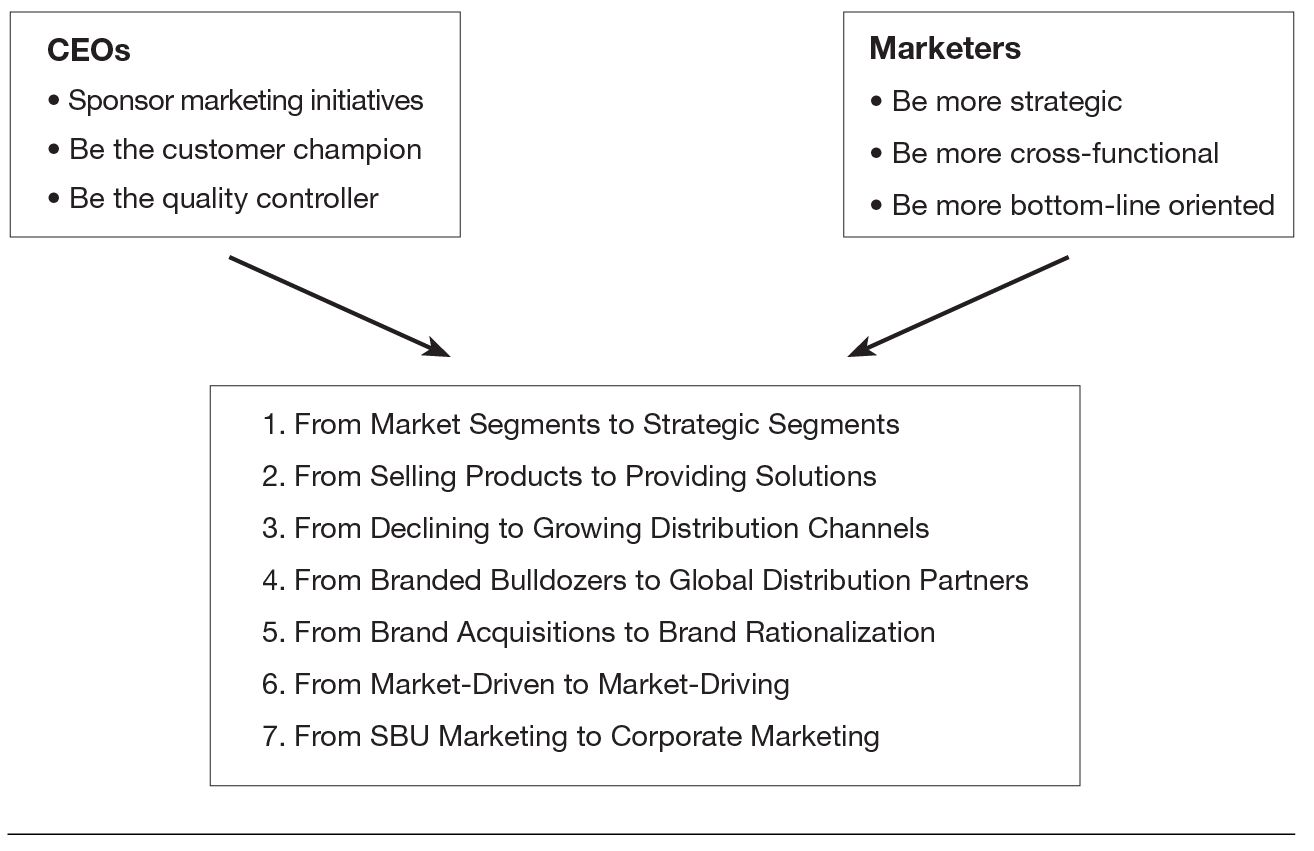

Sales Versus Marketing Orientation

In the 1960s, Philip Kotler popularized the marketing concept that profits are not the objective but the reward for creating satisfied customers (see figure 1-2). Whereas a sales-oriented company makes products and then seeks customers through sales and advertising, the marketing-oriented firm finds customer needs and then deploys an integrated marketing mix (made up of the popular four Ps) to satisfy them.47

We must reaffirm the fundamental purpose of a corporation: to serve customers over time and not to maximize shareholder wealth. I call this consumer capitalism, where companies generate a fair profit to reinvest in the business and to continue serving customers. Lee Scott, CEO of Wal-Mart, described Wal-Mart’s entry into financial services as an opportunity: “I’d like to do it more along the Wal-Mart way than other people’s. Rather than pricing off the market and [saying] if the market’s at 70 percent margin, we could be at 50 percent and make a lot of money and still be cheaper, I’d rather say, what is a fair return on doing that?”48 To illustrate, Wal-Mart plans to offer payroll check cashing at a flat $3 charge compared to its rivals’ 3 to 6 percent commission.

Consumer capitalism outshines North America’s shareholder capitalism (maximize shareholder value) or Europe’s more diffuse stakeholder capitalism (balance the needs of employees, shareholders, communities, and environment). Companies must rediscover mission statements like that of Aravind Eye Hospital in India: “To eradicate needless blindness by providing appropriate, compassionate, and high-quality eye care to all.” Johnson & Johnson has rallied around a one-page credo for over fifty years:

Our first responsibility is to the doctors, nurses and patients, to mothers and fathers and all others who use our products and services. In meeting their needs everything we do must be of high quality. We must constantly strive to reduce our costs in order to maintain reasonable prices. Customers’ orders must be serviced promptly and accurately. Our suppliers and distributors must have an opportunity to make a fair profit.49

The purpose of companies is to serve their customers’ needs and create value for them. Creating customer value requires the entire organization to function in a coordinated manner, not just the marketing department. If we consider the pathologies of power—seeking unilateral control, guarding turf, withholding information, and nonparticipation—with the many other problems of assigning ownership to a particular group, then we clearly see that responsibility and accountability for marketing belongs jointly to the CEO and the top team, senior line managers, and marketing specialists.50

Conclusion

Whereas the challenges facing marketing are many, the good news is that marketing has perhaps never had a more auspicious time to take leadership through organization-wide transformations that have top- and bottom-line impact. The forces altering the marketing landscape compel companies to strengthen their marketing efforts. As a former CEO of Procter & Gamble stated, “We are not banking on things getting better, we are banking on us getting better.”

Companies now realize that they increasingly draw value from intangible market-based assets, not physical ones. Which would affect Coca-Cola’s market value more: a loss of all its factories overnight, or the erasure of its brand name from human memory? Clearly, the latter would hurt more. Brands, customers, and distribution networks are the crown jewels in any company, and marketers are their main custodians.

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, marketers face the challenge of change. Power in organizations is moving away from those with marketing expertise tied to specific countries and industries. As industry and national boundaries are blurring, the ability to think across industries, transcend culture, and find universals is emerging as the new necessity.51 The demand from CEOs is for foresight rather than hindsight, for innovators, not tacticians, and for market strategists, not marketing planners. Marketers must learn to lead with imagination driven by consumer insight and not rely on market research for predictions. As marketers, are we ready to face these challenges? We have nothing to lose except hierarchies, national and functional boundaries, and, most of all, the four Ps.