TWO

From Market Segments to Strategic Segments

If you went out of business, would anyone miss you?

MARKETING’S BASIC MISSION is to create a difference between a company’s offering and that of its competitors on an attribute important to customers. To create differentiation, marketers use segmentation, targeting, and positioning, or STP. Market segmentation is the process of dividing the market into homogeneous groups of customers who respond similarly to a particular marketing mix of the four Ps—product, price, place, and promotion—the essential tactical tools for positioning the firm’s offer to the targeted segment. Not surprisingly, any marketing practitioner can comfortably converse in terms of market segments, target markets, and positioning.

One of the biggest frustrations of CEOs is their marketers’ inability to create such perceived differentiation among offerings. The tactical orientation has led marketers to rely too heavily on the marketing mix, which has limited how deeply they can differentiate in strategic segments. This deeper differentiation is critical to create distinguishing benefits that are sustainable and avoid commoditization.

In contrast to the relatively shallow market segment differentiation created through the exclusive use of the four Ps, deep differentiation is achieved by building the firm’s source of competitive advantage into the value network that serves a particular strategic segment.1 The value network—the cross-functional orchestration of activities necessary to effectively serve the chosen segment—includes differentiation based on the four Ps.2 But it also goes beyond marketing, to encompass differentiation on other functions such as R&D, operations, and service.

This chapter begins by describing how marketers view segmentation. The remainder of the chapter, however, will be devoted to advancing a new way to conceptualize segments based on the distinction between market segments, which require unique four-P constellations, and strategic segments, which require unique value network configurations. This distinction between market and strategic segments has far-reaching consequences for an organization and its source of competitive advantage.

To address the cross-functional implications of serving strategic segments, rather than limit themselves to the tactical four Ps, marketers must think more broadly in terms of the valued customer, value proposition, and value network, which I refer to as the three Vs. Conceptualizing strategic segments and using the three Vs model makes marketing more malleable and able to address important questions such as: How does a firm create sustainable differentiation? What are the cross-functional implications of serving a particular segment? What positive or negative synergies exist in serving combinations of different segments? Where should the value network be sliced to serve different segments? How unique is our marketing concept? What are sources of our differential advantage in terms of competences, processes, and assets? These are the strategic issues with respect to segmentation and differentiation that are going to excite CEOs, not the tactical four Ps that marketers traditionally focus on.

Market Segments: Divided by the Four Ps

Let us start by examining how marketers have traditionally conceptualized market segments and used them in practice. Conceptually, marketers begin by identifying market segments, then selecting the appropriate segment(s) to target, and finally positioning the company’s offer within the targeted segment(s) using the four Ps. Of course, in practice, segmentation is a messier process.

Market Segmentation

Customers within any market rarely have similar needs and expectations. To uncover the various segments into which customers fall, the segmentation process identifies variables that will maximize the differences between segments while simultaneously minimizing the differences within each segment. Creative segmentation can help a company get closer to its customers by developing the appropriate differential marketing mix for each segment, through changes in one or more of the four Ps.

The ultimate segmentation scheme from the customer’s perspective is mass customization, where each customer is a distinct segment. A popular example of mass customization is Dell Computers. Dell has the ability to configure each of its personal computers in response to an individual customer’s needs. For many other companies, the adoption of flexible production systems, quick-response supply chains, and shorter product development cycles has resulted in a relatively low cost for variety, enabling these companies to get closer to the ideal of mass customization. Competitive pressures are also forcing companies in this direction. As the CEO of a European company remarked a few years ago: “In the 1980s we looked for the customer in each individual. In the 1990s we must look for the individual in each customer.”3 However, most companies still must trade off between the company’s logic, where economies of scale push for larger and larger segments, and the customer’s logic, which drives companies toward recognizing the unique needs of the individual customer.4

The variables on which segmentation can occur are potentially numerous. In this sense, segmentation is an art. It is a lens through which to view the population of customers in an industry. Markets must be continuously segmented and resegmented to arrive at a scheme that delivers actionable segments. Actionable segments share three characteristics: (1) distinctiveness, that is, different segments respond differentially to the marketing mix; (2) identity, that is, the ability to reasonably profile which customers fall within which segment; and (3) adequate size, so that the development of tailored marketing programs for individual segments is economically viable for the firm.

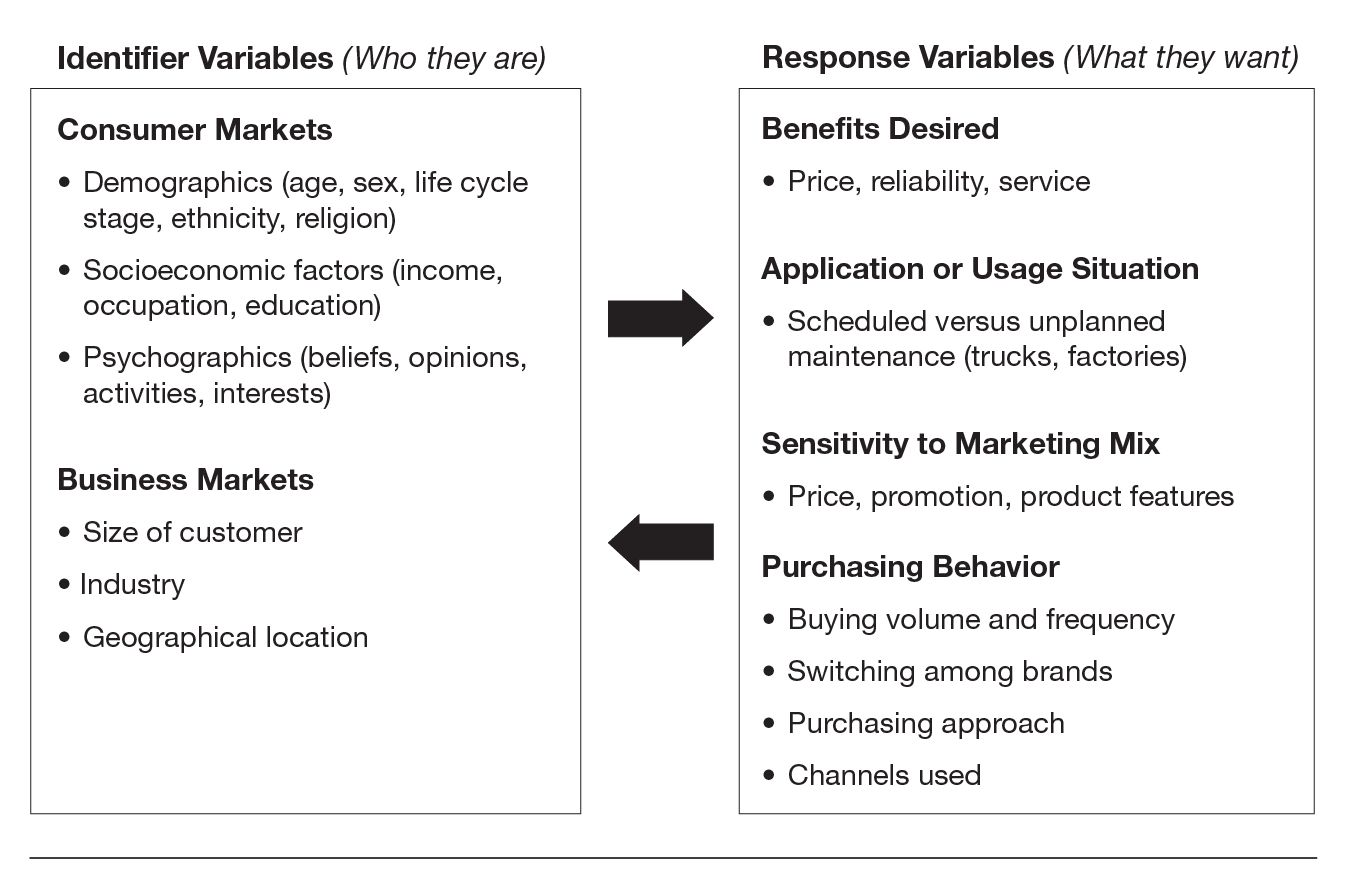

Segmentation variables can be broadly classified into two categories : identifier and response. Identifier variables begin by segmenting the market based on who the customers are, in the hope that the resulting segments behave differently in response to marketing mix variables. This is called a priori segmentation. Examples include segmentation schemes that are based on sex, age, education, and income in consumer markets, or size of firm, industry, and geographical location in business-to-business markets. In contrast, post hoc segmentation starts by using response variables to divide the market on the basis of how customers behave, and then hopes that the resulting segments differ enough in terms of customer profiles to enable identification. An example would be segmenting telecommunication customers based on those whose primary concern is price versus those who are fixated on reliability or service quality. Figure 2-1 lists some commonly used segmentation variables.

In practice, managers need both a priori and post hoc processes to fine tune their understanding of market segments. Unfortunately, many firms frequently rely too heavily on a priori segmentation variables. For example, size of the firm is a popular means of segmenting customers in business markets. However, the resulting three segments of small, medium, and large firms, while easy to profile, rarely differ enough in terms of their needs or behavior. Some small firms are looking for the same benefits as some large firms, and vice versa.

Common Market Segmentation Variables

Targeting

Targeting or target market selection is the process of deciding which market segments the company should actively pursue to generate sales. Firms choose between adopting undifferentiated, differentiated, or concentrated targeting strategies. An undifferentiated strategy attempts to target all customers with the same marketing mix. The most famous example is Henry Ford’s alleged 1908 declaration about the Ford Model T: “You can paint it any color, as long as it is black.” While this seems like an anathema to the marketing concept, there are conditions under which it is appropriate. If standardization lowers the cost of delivering the value proposition to unprecedented levels and opens up the industry to large numbers of new customers, then an undifferentiated strategy can be powerful.

A differentiated strategy simultaneously targets several market segments, each with a unique marketing mix. For example, Ford Motor Company today has a portfolio of brands, including Aston Martin, Ford, Jaguar, Land Rover, Lincoln, and Volvo, to attack various segments in the automobile market.

Finally, a concentrated strategy selects one segment and concentrates on serving it, as Porsche has historically done with its over-forty, male, college graduate, with income over $200,000 per annum segment. However, Porsche subsegments using psychographics : Top Guns are driven, ambitious types who expect to be noticed and care about power and control; Elitists are old-money blue bloods who consider a car to be transportation, not an extension of one’s personality, no matter how expensive; Fantasists are Walter Mitty types who escape through their cars and feel guilty about owning one; Proud Patrons consider ownership an end in itself, a trophy for hard work; and Bon Vivants are worldly jetsetters and thrill seekers whose cars heighten the excitement in their already passionate lives.5

Positioning

Positioning is about developing a unique selling proposition (USP) for the target segment. A company’s unique selling proposition should be both unique, that is, differentiated from other competitors, as well as selling, that is, appealing to the target customers. It is the reason that the firm exists in the marketplace and why consumers would miss the company if it ceased operations. A well articulated USP should be capable of being briefly communicated by completing the sentence: “You should buy my product or service because . . .” In completing this sentence, the answer should be driven by customer benefits, not product features. Much of the disappointment of CEOs is rooted in the failure of marketers to answer this question in a compelling manner. The inability to do so results in either a price negotiation with the customer or a loss of the sale.

Volkswagen in the United States targeted a younger, more educated, more affluent demographic, and an adventurous, confident psychographic of customers who enjoy driving and even disobey speed limits. It positioned itself rationally as “affordable and German engineered,” and emotionally as a “different driving experience more connected to the road and world.” Compared to Nissan, Honda, Mazda, and Toyota, customers perceive VW to be more drivable, more substantial, more individual, and more spirited. Compared to BMW, Saab, Mercedes-Benz, and Volvo, VW is more approachable, more likeable, a better value, and more human.6 The point: Companies must be very specific in terms of their intended positioning or unique selling proposition if they are to have any hope of being able to stand out among the clutter of choices confronting customers.

Complex Segmentation: Midas Style

Symptomatic of marketing’s tactical orientation is the received wisdom on segmentation summarized above. The concept of market segments is about determining how to change the marketing mix, the four Ps, to serve different segments. Market segmentation helps the marketing manager determine which marketing mix to deploy to serve each unique segment.

Segmentation in companies is a more complex and messy process than in textbooks. To reveal how market segments operate in practice, let us examine Midas and the automobile repair business. 7 Midas offers consumers walk-in service for repairs on brakes, mufflers, and exhaust pipes. It segments its customers using three identifying variables: (1) age of the car, because the older the car, the more likely the customer will need Midas; (2) size of the car, since the bigger the car, the higher the value of the sale and the higher the margin; and (3) sex of the driver, since women are more likely to buy additional services. In response to this segmentation, it changes its marketing mix based on the customer and the characteristics of his or her car.

The market segmentation at Midas does not stop there. It has also discovered two service segments of customers, car lovers and utilitarians, based on service expectations and needs. The car lovers see their car as a prized possession, while the utilitarians tend to view their car as merely a means to take them from one place to another. Both segments want the same basic value proposition from Midas: fast, reliable, one-time repair. However, to completely satisfy both segments, Midas varies the additional services that surround this value proposition.

The service personnel interacting with the car lover focus the discussion on the car, offer opportunities to observe the repair while the car owner is waiting, provide old parts in the packaging of the new parts to show tangible evidence that the parts have been changed, and follow up with phone calls every six months to remind the customer that it is time for another check-up. The utilitarian would consider all of these services to be annoying. Instead, the service personnel talk to these customers about their lives, offer them a newspaper or a game to play while waiting, reassure them that the little noise is now gone, and guarantee the car for X number of miles without the problem recurring.

Strategic Segments: Divided by the Three Vs

Market and service segments such as the above, which only require changes in the marketing mix, can be distinguished from strategic segments. Strategic segments are those segments that require distinct value networks, rather than just changes in the marketing mix. For example, Midas caters to the strategic segment that wants “fast mechanical repair” in the auto repair business, as opposed to the “guaranteed repair” offered by factory-authorized car dealers, “specialty repair” offered by the independent workshops, “heavy-duty accidental repair” performed by body shops, or the “do-it-yourself repair” for the automobile enthusiast. Each of these strategic segments is associated with a unique set of key success factors.

The identification of strategic segments helps the business unit manager determine which value network to deploy. If a company wishes to serve two different strategic segments, then it must develop two unique value networks. Instead of simply aligning the four Ps, as is the case with market segments, serving different strategic segments requires the alignment of other functions such as R&D or operations. As a result, instead of the four Ps, I find it more appropriate to think in terms of the three Vs—valued customer, value proposition, and value network.8

Let us use the airline industry to illustrate in greater depth the concept of strategic segments and the three Vs model. In Europe, the leading low-cost airline is easyJet, which is modeled after Southwest Airlines in the United States.9 EasyJet has seen extraordinary success since November 1995, when it offered to fly travelers from London to Glasgow for a one-way fare of £29 with the slogan: “Fly to Scotland for the price of a pair of jeans!” Under the colorful leadership of its founder Stelios Haji-Ioannou (who prefers to be addressed by his first name only), easyJet has become a thorn in the sides of the traditional European Flag Carriers such as British Airways, Air France, KLM, and Swiss. Comparing the Flag Carriers and easyJet on the three Vs highlights the power of strategic segments.

Valued Customer—Who to Serve?

On the first V—valued customer, or who to serve—the traditional Flag Carriers like KLM and Swiss target everyone; however, their most valued customers are business travelers. In contrast to business travelers who pay from other people’s pockets, easyJet targets those customers who pay from their own pockets. While these tend to be predominantly leisure travelers, there are business people such as entrepreneurs and small business owners who also pay from their own pockets. Altogether, this is a large segment in Europe and one that was unhappy with the industry offerings until low-cost airlines such as easyJet and Ryanair emerged. These two segments are strategic segments because serving them effectively requires distinct value networks, rather than simply a differentiation of the marketing mix.

Value Proposition—What to Offer?

Value proposition, or what to offer to the valued customers, reveals stark differences between the two segments. Business travelers, whose bills are paid by their companies, are demanding, both in terms of services, such as seat comfort and business class, as well as freebies, such as free newspapers, meals, and frequent flyer miles. More legitimately, they also need seat selection, travel agents, and a worldwide network to save time, make seamless connections, and have the flexibility to change flights to accommodate their hectic schedules.

In contrast, while leisure travelers may enjoy the above services, when given the choice, they will forgo all of them for a lower price. Four questions developed by Professors Kim and Mauborgne provide a framework for understanding the creation of easyJet’s value proposition, and should be addressed by every company.10

- Which attributes that our industry takes for granted should be eliminated? This question forces companies to reflect on whether each of the attributes offered creates value for their valued customers. EasyJet’s conclusion was that free meals and travel agents could be eliminated. Instead, it sells snacks on the plane and 95 percent of its seats are sold through the Internet, while the remaining 5 percent are processed through their call center.

- Which attributes should be reduced to below industry standards? This question pushes companies to consider whether the industry has overdesigned its products and services for their valued customers. EasyJet concluded that it could reduce flexibility in flight changes and seat selection offered to passengers. All fares at easyJet are nonrefundable. However, if another flight is available, passengers may change flights by paying a penalty of £10 per leg plus the difference in fares between the two flights. Seating is on a first-come, first-served basis. At check-in, passengers get a group boarding number tag, such as 1–25 or 26–50, so that they will arrive early for a good seat. Then, when boarding is announced for the passengers’ group tag, they take any available seat, thereby accelerating the boarding process. At other airlines, aircraft often wait for passengers with preassigned seats who lack incentive to board quickly.

- Which attributes should be increased to above industry standards? This question presses companies to understand the compromises that the industry currently forces its customers to make. For example, compared to the rest of the industry, easyJet strives for lower prices, greater punctuality, and a younger fleet of airplanes.

- Which new attributes should be created that the industry has never offered? This question forces companies to think about what new sources of value creation exist within the industry. On this dimension, easyJet decided to offer only one-way fares, refunds if there is a delay of four hours or more, and ticketless travel.

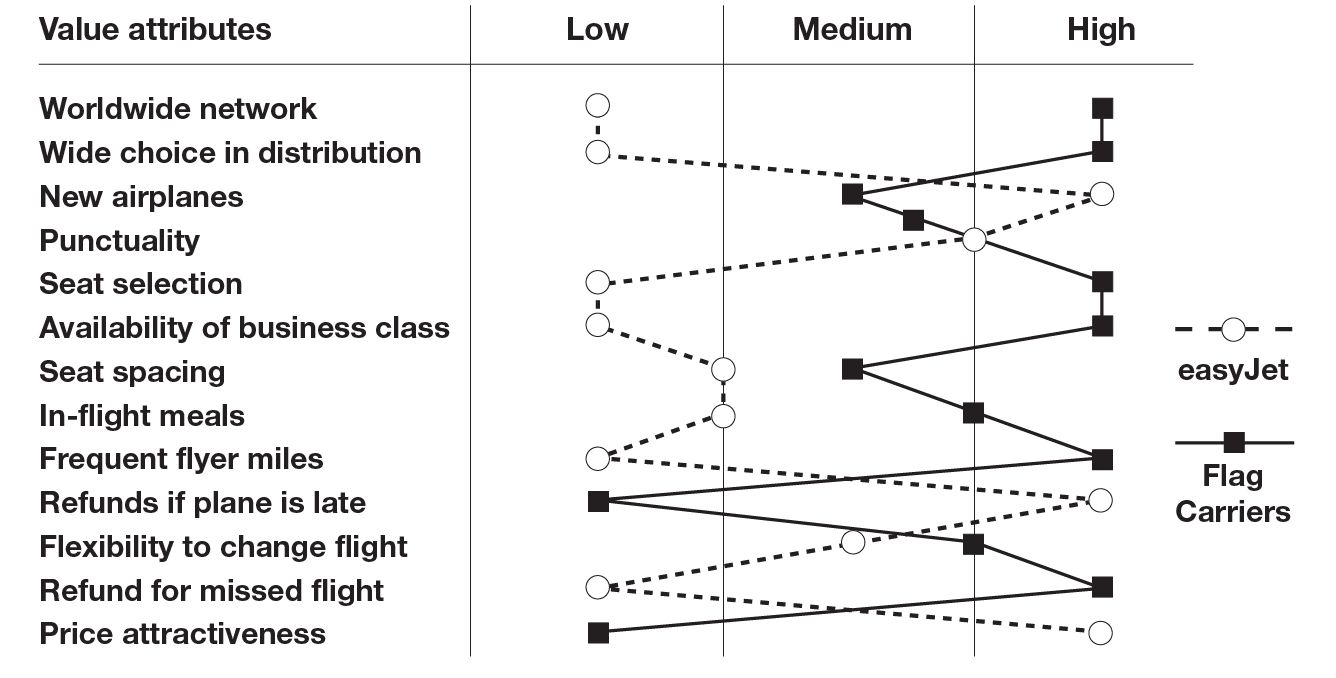

The value proposition of easyJet can be graphically contrasted with that of the Flag Carriers using a tool called the value curve. 11 As can be seen from the value curves in figure 2-2, the Flag Carriers are superior to easyJet on almost every dimension. But consider the attributes that are most important to air travelers. First, they want to reach their destination safely. The low price of easyJet raises particular concern in this respect. How can easyJet make safety, which is an intangible benefit, tangible? New planes are the obvious answer. Second, they want to arrive on time. By offering refunds if the plane is more than four hours late, which is rather difficult for the short hauls that they operate on, easyJet makes punctuality a perceived benefit. Along with these two benefits, it offers low prices and in return asks its customers to trade off all other attributes that they may get from a full-service airline. It has stripped the value proposition to its bare bones, beating the competition only on the absolutely necessary dimensions of the value proposition for its valued customers.

Value Curves of easyJet Versus Flag Carriers

Value Network—How to Deliver?

On the third V—value network, or how to deliver the value proposition to the valued customer—easyJet has systematically redefined each component to deliver low prices at a profit. It achieves distribution savings of about 20 to 25 percent over other full-service carriers by not using travel agents, encouraging Internet sales, not participating in industry reservation systems such as Sabre, and not issuing paper tickets. Ten percent of its budget is spent on marketing, but it gets a much bigger bang for its buck by having in-your-face, attention-grabbing, opportunistic advertising that generates loads of free publicity. In addition, through the use of a sophisticated yield management tool it can maximize the revenues for each flight based on dynamic matching of supply and demand. As demand for a flight goes up, prices increase, and vice versa.

While the transformations in the marketing and distribution components are important, much of the savings in its value network is generated through radically streamlined operations (see figure 2-3 for a comparison of the value networks of easyJet with those of Flag Carriers). EasyJet’s operations are optimized for low costs through fast turnaround (the amount of time the plane is on the ground between flights) and greater utilization of airplanes. The exclusive use of a single type of airplane, the Boeing 737, reduces spare parts inventory, as well as training costs for pilots and maintenance personnel. It increases flexibility in interchanging planes, strengthens bargaining power with the vendor, and makes the yield management system easier to operate since the configuration of each plane is identical. The elimination of the kitchen and business class enables it to fit 149 seats on a Boeing 737 compared to 109 for the competition. The lack of preassigned seating increases punctuality and turnaround time.

Value Networks of easyJet Versus Flag Carriers

Reinventing the Value Network. At a more abstract level, there are five cost principles behind the construction of easyJet’s value network:

- Avoid fixed costs whenever possible. For example, there are no secretaries in the organization. Even the CEO, Ray Webster, must open his own e-mails!

- If there are any fixed costs, make them work harder than the rest of the industry. For example, easyJet planes are in the air for 11 hours a day, compared with the 6.5-hour average for the industry.

- Eliminate generally accepted variable costs whenever it makes sense, such as travel agents.

- Keep any variable costs to a minimum, such as airport fees.

- Examine whether variable cost factors associated with services can be converted into revenue generators, as easyJet has done by selling snacks on the plane.

While perhaps not as applicable as they are for easyJet, these are principles that all firms could adopt.

Drive Growth and Innovation Using the Three Vs

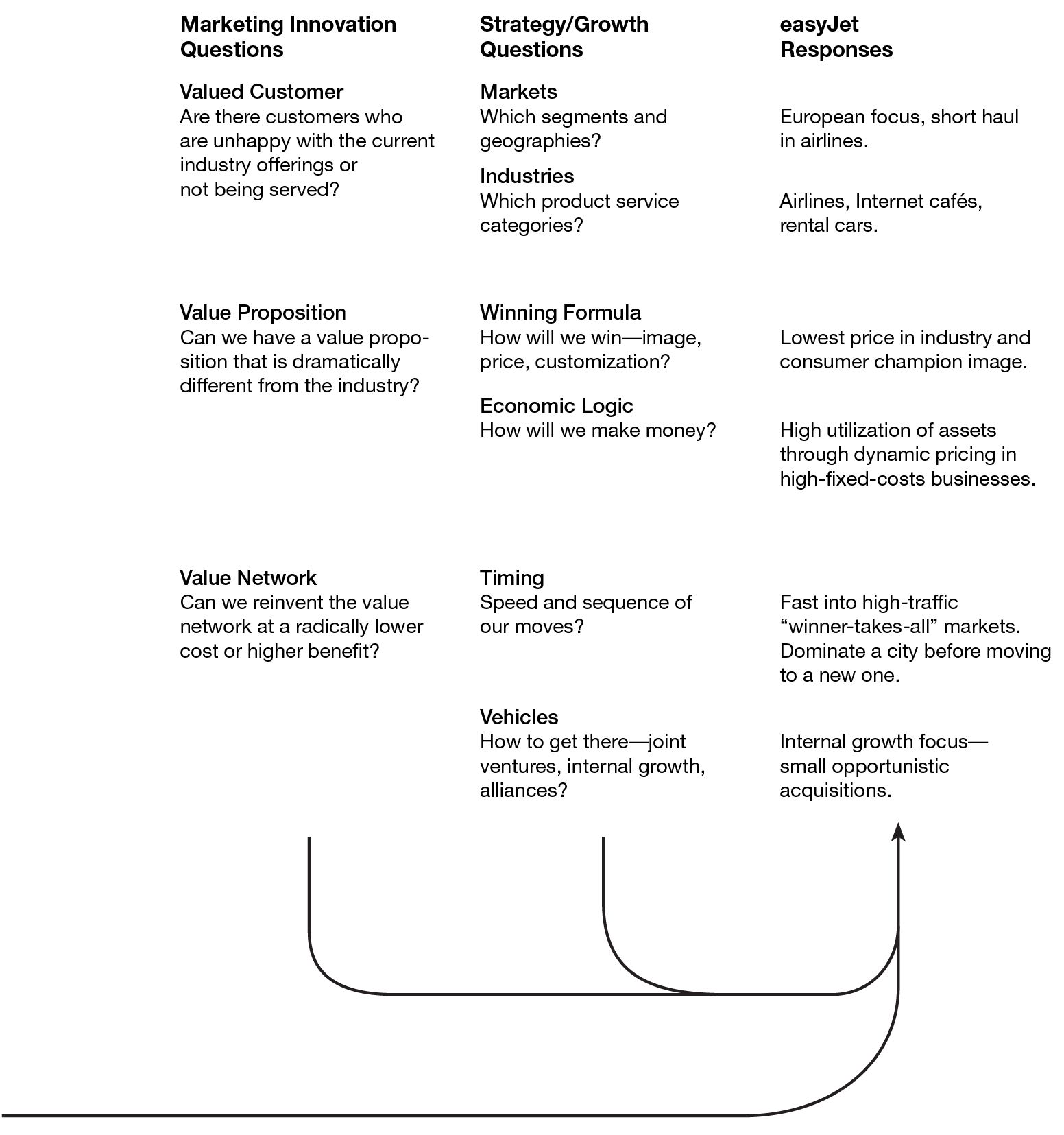

Comparing easyJet and the Flag Carriers along the three Vs generates several interesting propositions related to strategic segments (see table 2-1).

easyJet Versus Flag Carriers on the Three Vs

| Flag Carriers | easyJet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valued Customer | Everyone, especially business class | People who pay from their own pockets and some who don’t typically fly | ||

| “Who to Serve?” | ||||

| Value Proposition | • | Flexible | • | One-way fares |

| “What to Offer?” | • | Full-service | • | No frills |

| • | High prices | • | Low prices | |

| Value Network | ||||

| “How to Deliver?” | ||||

| Purchasing | Integrated | Outsourced | ||

| Operations | • | Multiple types of planes | • | Single type of plane |

| • | Short- and long-haul routes | • | Short-haul routes | |

| • | Worldwide network | • | Select destinations | |

| Marketing | • | Segmented customers | • | Treat all customers the same |

| • | Varied meal services | • | “Focused” | |

| • | Frequent flyer program | |||

| Distribution | Travel agents/all channels | Internet/direct sales only | ||

Differentiate Deeply Based on the Value Network

Much of the competitive advantage of each type of company lies in distinct value networks. British Airways may try to offer easyJet’s low fares, but it will never make a profit doing so. So it launched GO, a low-price subsidiary, to compete with easyJet and Ryanair. However, when GO was part of British Airways (BA), the temptation was to constantly seek synergies in the value chain. Because these two airlines were serving different strategic segments requiring divergent value networks, any attempt to exploit synergies hurt both subsidiaries. The so-called synergies, or shared portions of the value network, were neither optimized for the low costs necessary for GO, nor the full service necessary for BA. As a result, BA divested GO and let it try to survive as an independent firm until easyJet eventually acquired it. In contrast, if one is serving two market segments, then much of the value network may be shared.

Firms need to align the three Vs. One cannot serve easyJet’s valued customers with the easyJet value proposition and have the value network of the traditional full-service airline company. The margins would simply be too small to generate a profit. Alternatively, one could not offer the full-service value proposition of the traditional airline with the value network of easyJet. The customer expectations with respect to service would never be met. When developing the three Vs, a company should ask: (1) To what extent does our marketing concept differ from others in the industry? (2) To what extent do elements of our marketing concept mutually reinforce each other?12

Unlike decisions to serve new market segments, entering a new strategic segment requires a new value network, and is thus a major decision for the company often requiring the approval of the board of directors. For example, KLM operated its low-cost carrier, Buzz, as a separate subsidiary and even looked for outside investors to help fund the expansion of Buzz. Yet, because there were no synergies between KLM and Buzz, Buzz was ultimately sold to Ryanair, despite the fact that low-cost air travel is the fastest growing and only profitable segment in the European airline industry.

Explore Different Value Network Options for Unique Segments

Many companies are struggling with the question of where to slice the value network to serve different segments. Consider the major food companies such as Danone, Nestlé, and Unilever, which sell famous branded products like Danone yogurt, Nescafé coffee, and Magnum ice cream through retailers. The increasing power of retailers combined with time-starved, affluent consumers has eroded grocery sales of branded products from 52 percent to 33 percent of the total consumer spending on food from 1982 to 1990 in the United Kingdom.13 On one hand, private labels pushed by powerful retailers have increased their share from 33 percent to 46 percent. On the other hand, time-impoverished consumers with greater disposable income have helped increase the share of eating out from 15 percent to 21 percent.

In response to these consumer patterns, the multinational food companies have begun manufacturing private labels for major retailers as well as launching into the food service business by developing products and packaging specifically targeting hotels, restaurants, and cafeterias. As food companies try to serve the consumer segments that buy private labels or eat out, the issue of value network segregation is constantly raised.

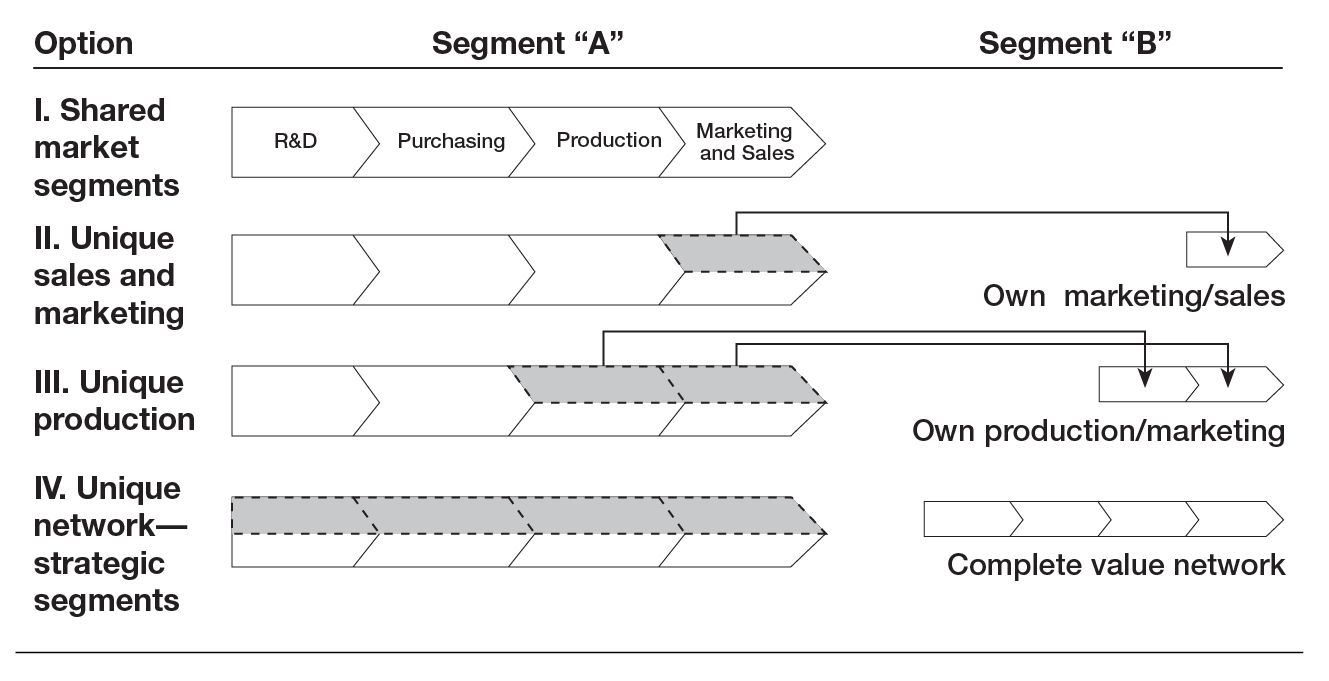

Within these companies, the executives responsible for managing food service often complain that their business has completely different research and development needs and does not receive adequate attention from the firm, despite being the high-growth sector in the company. They argue that the food service business is a strategic segment requiring a unique value network. Other executives in the same companies argue that the food service business is a market segment that can be managed effectively in combination with the branded products business. Their perspective is that each should have a dedicated sales force and unique packaging, but R&D and manufacturing should be shared between the two. As this example demonstrates, there is a continuum between strategic and market segments. Figure 2-4 shows the different value network options for market versus strategic segments.

Value Network Options for Market Versus Strategic Segments

Analyze the Financial Implications of Serving Segments

Similar, but in my experience more heated, arguments occur on whether the private labels and branded businesses represent strategic segments. The issue is more difficult here as both the branded products and the private labels are usually sold to the same retailers. Thus the incentive to share logistics, sales force, and marketing is significant. However, the value network for profitable private labels differs significantly from that of branded products.

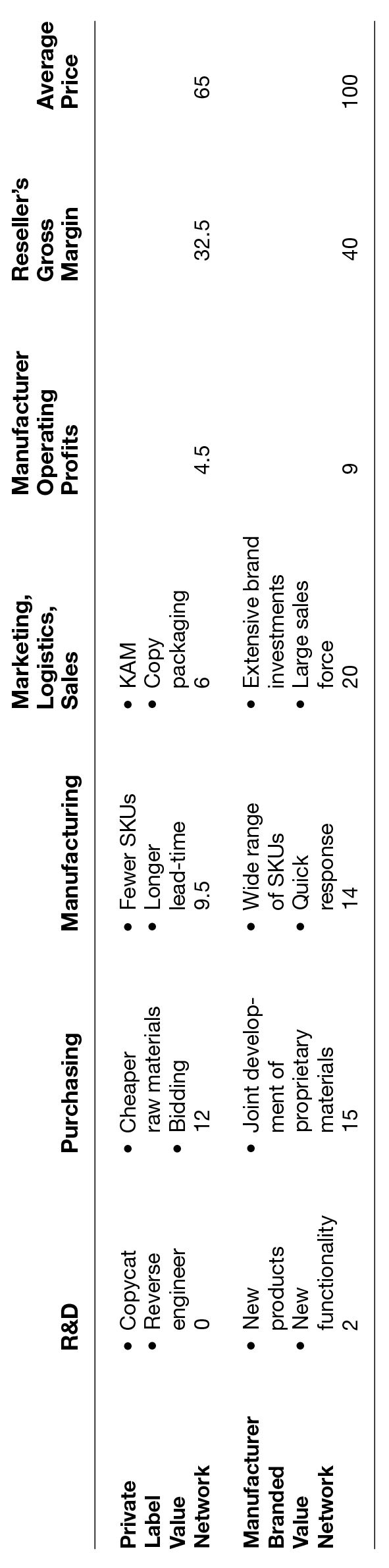

Table 2-2 offers a disguised example from the consumer packaged goods industry benchmarking the value networks of the most successful private label manufacturer against the leading branded manufacturer. Both companies were focused, that is, the branded manufacturer did not engage in manufacturing private labels for retailers and the private label manufacturer did not sell any products under proprietary brand names. On average, the price for the end consumer of the private label product was 35 percent lower (hence the consumer price index of 65 for private labels versus 100 for branded manufacturer).

Compared to branded products, the average retailer margin on private labels was larger in terms of percentage (50 percent versus 40 percent) but smaller in terms of absolute dollars ($32.50 versus $40). Both the private label manufacturer (4.5/32.5) and the branded manufacturer (9/40) had operating profit margins of around 15 percent on sales. However, they achieved this by optimizing the value network in completely different ways.

The private label manufacturer had almost no research and development and instead relied exclusively on copycat innovations. It utilized cheaper raw materials and aggressive buying practices. Since it supplied only a few very large retailers, the number of stock-keeping units (SKUs) were relatively small and the rather transparent purchasing pattern of its customers allowed longer lead times in manufacturing. This helped run an efficient supply chain that lowered costs significantly. In addition, all the retailers were served through a single key account manager (KAM), and few resources needed to be devoted to developing packaging as they adopted me-too packaging.

Value Networks of Private Label Versus Branded Business

The branded manufacturer invested in research and development to generate new products and functionality for consumers that sometimes required partnering with suppliers to develop proprietary materials. It had an expensive manufacturing system that was set up to produce a wide range of SKUs to satisfy the many different retailers and target segments served. Differentiation was also built into the system through quick response capabilities. However, the largest additional cost was in building the brand through expensive advertising and promotional campaigns as well as a large, well-educated sales force.

In contrast to these two value networks, a third company’s sales were derived equally from private labels manufactured for major retailers and its own manufacturer brands. Many of the latter were among the leading brands in their respective countries. Unfortunately, because its value network was integrated, the company was actually just about breaking even, despite being among the largest players in the industry.

Sharing the value network compromised the integrity of the branded product since retailers were extremely savvy at transferring benefits (quality, innovations, packaging) from the branded line into their private label, while paying the private label price. However, in continuous process industries such as toilet paper or aluminum foil, value network separation at the level of purchasing and manufacturing would severely compromise production efficiencies.

Given the distinct nature of the two value networks, the company was advised to choose among the following three options:

- Concentrate exclusively on being either a branded or a private label player.

- Become primarily a branded player, but accept private label manufacturing only under very strict criteria: meet a hurdle rate of return on sales, use only excess plant capacity, and do not “borrow” packaging or recently introduced innovative features of the company’s branded product.

- Completely separate the private label business from the branded business and let each optimize its own value network.

After much debate, the company chose the last option rather successfully.

Over and over again, in the face of nimble new competitors such as Charles Schwab, Dell, easyJet, Hennes & Mauritz, and Wal-Mart, companies must confront the issue of slicing the value network after analyzing the financial implications. Usually, they cannot change because their corporate mind-set clings to the old value network. British Airways, Continental, Delta, KLM, and Lufthansa all chose to divest their low-cost airlines, despite the latter competing in the faster growing, more profitable, and ultimately higher market capitalization segment.

Drive Marketing Innovation Using the Three Vs

Marketing innovation can be conceptualized using the three Vs model by asking three questions:

- Are there customers who are either unhappy with all of the industry’s offerings or are not being served at all? Through posing this question, one can find tremendous opportunities to exploit. Think of all the HIVPOSITIVE people in Africa. The value networks of the major multinational pharmaceutical firms—characterized by sophisticated R&D, expensive insurance reimbursement–driven pricing practices, high marketing costs, and large profit margins—will never be able to generate a solution for them. Instead, these patients are waiting for a visionary to develop an “easyJet” value network that will deliver effective treatment to them. Or consider Progressive Insurance’s successful focus on high-risk individuals whom no other insurance company will cover.

- Can we offer a value proposition that delivers dramatically higher benefits or lower prices, compared with others in the industry? Virgin’s ability to pamper its passengers with massages and manicures is an example of a strategy driven by higher benefits. Or consider Zara’s strategy of copying catwalk fashions and offering them to customers faster and cheaper than the designers themselves can bring them to the market. The value curves are a clever way of clearly differentiating one’s value proposition. A graphic value curve is hard to fudge, forcing one to confront whether, and where, the firm’s value proposition is truly differentiated.

- Can we radically redefine the value network for the industry with much lower costs? Dell in the personal computer business, Formula 1 in the hotel industry, and IKEA in furniture retailing are diverse examples of companies that have achieved this.

The four value proposition questions presented previously and the three questions above help conceptualize opportunities for marketing innovation in the industry. And using the three Vs to generate innovation clarifies that innovation is not the exclusive territory of technical R&D and product development people. Rather, marketers and strategists can contribute to innovation by discovering underserved or unhappy segments, offering new value curves, and reinventing industry value networks.

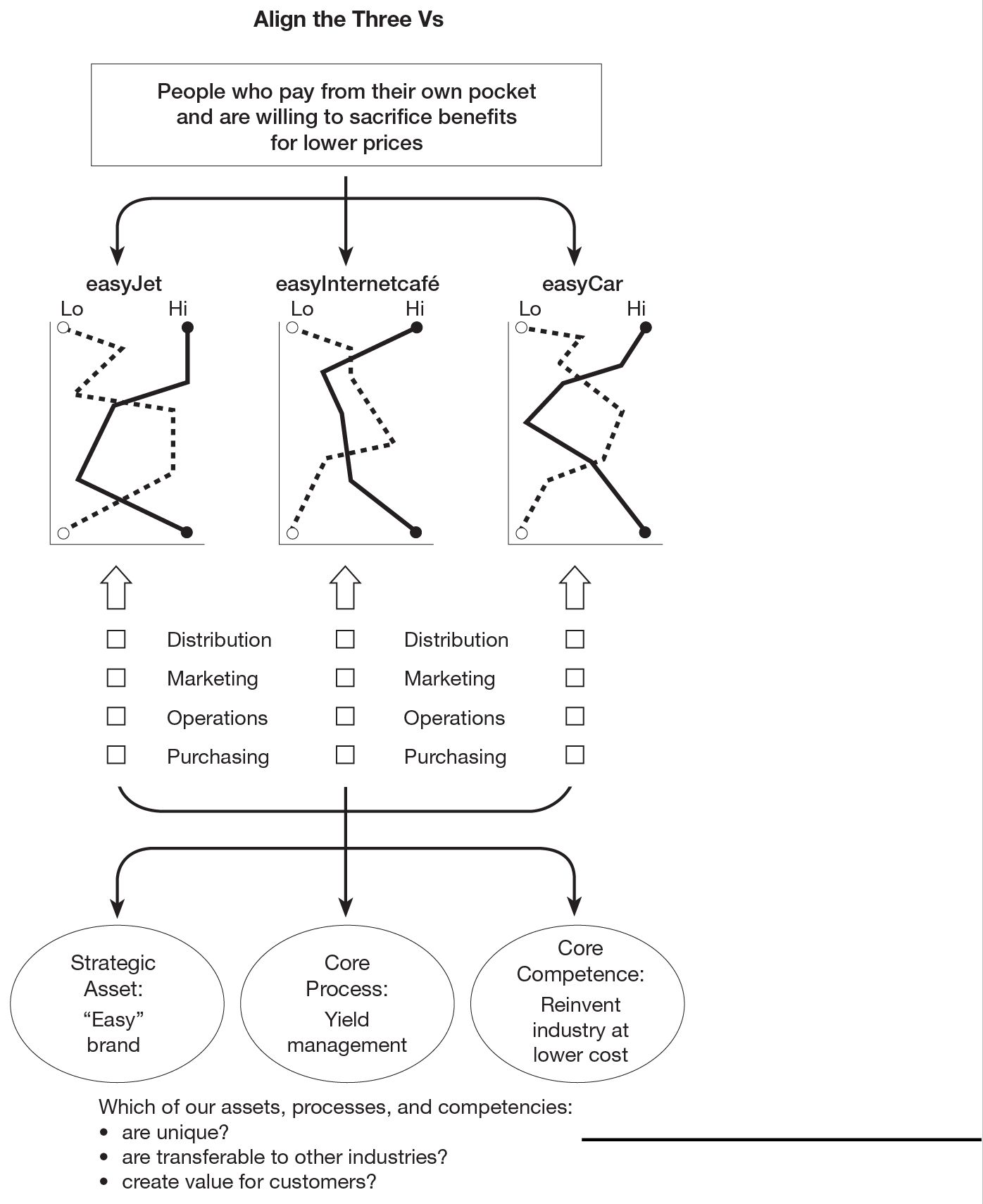

Exploit the Three Vs–Related Growth Opportunities

By combining the three marketing innovation questions from the previous section with an in-depth understanding of a company’s three Vs model, the company’s strategic growth map can be developed.14 Understanding where customers are not being served helps determine which markets and industries the firm should operate in or “who to serve.” Clarity in the winning formula and economic logic create the potential to offer dramatically different value propositions and help determine “what to offer.” Finally, the value network, or “how to deliver,” explicates the timing (when to move into which markets) and vehicles (how to get there) that will help enable the firm’s growth moves (see figure 2-5).

Stelios Haji-Ioannou has innovated and diversified into at least two new businesses since starting easyJet. EasyInternetcafé is the first chain of large Internet cafés in the world.15 These cafés, open twenty-four hours a day and located all over Europe (as well as one in New York), allow consumers to surf the Internet on flat screens using high-speed connections for about £1 an hour. EasyCar is an Internet-reservation-only rental car company, which offered, at least initially, Mercedes A-class vehicles exclusively, for a price as low as £9 per day.

Of course, Stelios has incorporated many of the ideas from easyJet into his two new businesses by constantly asking: What are our core competences (things we know), strategic assets (things we own), and core processes (things we do)?16 The core competence of easyGroup is redefining the value chain of an industry at a significantly lower cost. Its strategic asset is the “easy” brand as a consumer champion. Its core process is yield management–based pricing systems. All of these are unique to the company, create value for the consumer, and can be transferred to other businesses.17 They are the platforms for exploiting growth and diversification opportunities.

easyGroup Diversification

Checklist for Marketers on the Three Vs

Valued Customer

- Who are our valued customers?

- Are there customers who are unhappy with all the current offerings of the industry?

- Are there customers who have a need but are not being currently served by the industry?

- Are we trying to reach customers who are unaware that they need our product? If so, how are we going to create the need?

- Who is the user? The buyer? The influencer? The payer? What are the preferred criteria of each and their power in the buying decision?

- Is the target segment large enough to meet our sales objectives?

- What is the growth rate of the target segment?

Value Proposition

- What are the core needs we are trying to address with our value proposition?

- Does the value proposition fit the needs of our valued customers?

I have used the easyGroup of companies to illustrate the idea of strategic segmentation versus market segmentation and how to use the three Vs model for innovation and growth. This is not to imply that the easyGroup is without its challenges. EasyInternetcafés are still struggling to find a profitable business model. EasyJet is in the process of assimilating the GO acquisition. In addition, both easyJet and easyCar have moved away from the single type of aircraft and car models. Having a single supplier made the firm a hostage when it came to purchasing additional capacity. Thus Stelios is willing to trade off somewhat higher operating costs for lower aircraft or vehicle acquisition costs. The implications of this decision will not be known for some time.

- What benefits are we actually delivering to the customers?

- Is our value proposition differentiated from the competitors or are we positioning in a crowded space?

- Are our value proposition claims reinforced by underlying product and service features?

- Are we positioning on attributes that we can defend against competitive attacks?

- Are we positioning on too many benefits to be credible?

Value Network

- Can we serve the valued customers with the value proposition at a profit?

- Do we have the necessary capabilities to deliver the value proposition? If not, could we acquire or partner with them?

- Would serving the valued customers have negative consequences on our existing customers or businesses? If so, how are we going to control for this?

- Which high-cost or low-value-added activities could be eliminated, reduced, or outsourced in our value network?

- Where are the advantages of scale in our value network? Can we maintain scale while not losing flexibility?

- How different is our value network from the rest of the industry?

- What is our break-even point? Could we lower it by slightly varying the value network?

Conclusion

CEOs often fault marketers for not clearly communicating the value proposition of the firm and how it differs from that of the competition. The value curve tool and the three Vs approach can help marketers by constantly forcing them to ask the hard questions regarding segmentation, targeting, positioning, and the business model for delivering the value proposition. (See “Checklist for Marketers on the Three Vs.”)

Understanding strategic segmentation and then conceptualizing and responding to it using the three Vs model helps illuminate critical issues facing many companies. As companies enter and operate in related segments of businesses, are they facing strategic segments or market segments? How far back in the value network should they separate the two businesses? Is it enough to separate marketing, or should marketing and distribution be segregated? Or does one need a completely distinct value network for the new segment? How can marketing be used to generate innovation and growth in the industry? These are challenges related to segmentation that are currently on CEOs’ agendas. The resolution of these questions has strategic, cross-functional, and bottom-line implications. By using the three Vs lens to answer these questions, a company can find new strategic segments, build deep differentiation, and drive innovation and growth while transforming industries at the same time.