THREE

From Selling Products to Providing Solutions

Customers buy holes, not drills.

IN MANY INDUSTRIES, especially in business-to-business (B2B) markets, suppliers of “products” struggle to withstand commoditization. Competitors rapidly copy new features, effectively destroying product differentiation, and sophisticated buyers refuse to pay any brand premium—at least not a premium that would cover the required additional marketing costs to build and maintain it.

Companies confronting commoditization have few strategic options. They can become a low-cost provider in their industries, but that requires relentless cost-cutting, generally by moving production overseas to low-cost locations, trading low margins for (hopefully) higher volume, revealing cost structures to customers, and favoring sales over any real marketing function. In the commodity business, purchasing agents tend to drive customer interactions and as customers hold the power; sellers have little pricing flexibility. In response to this pressure, many companies instead aspire to become solution providers, by integrating bundles of their products with services for the customer. The business imperative for providing solutions is relatively clear. Compared to products, solutions include a large service component and therefore are less comparable. Over time, the seller masters the customer’s business processes. This makes changing suppliers difficult and costly for the customer and thereby increases customer loyalty. Furthermore, since selling solutions usually requires integrating a large number of products and services, the typical sale generates larger revenues.

Not surprisingly, the growth and profit mantra of industries as diverse as chemicals, financial services, health care, information technology, logistics, pesticides, telecommunications, and travel is to become a problem-solver for the customer, not simply a producer of products. Even Sun Microsystems, whose CEO Scott McNealy once said that service is what companies sell when they cannot sell products, now claims, “Sun’s Internet expertise, combined with innovative yet reliable end-to-end solutions and professional consulting services, makes Sun the ideal partner for delivering IP-based services!”1

Transforming the organization into a solutions provider is tricky. Few executives truly comprehend the enormity of the challenge, let alone what “solution provider” really means. But some companies are well on their way. Notably, IBM has successfully made the transition from mainframe giant to PC maker to end-to-end IT solutions provider.

The Turnaround of IBM by Selling Solutions

After leading the market for years, IBM hobbled into the 1990s.2 The company could no longer command price premiums as its competitors narrowed the gap in perceived quality. Between 1991 and 1993, IBM recorded losses of $16 billion; in 1993 alone it lost $8.1 billion on sales of $62.7 billion. Wall Street pressured IBM to spin off undervalued divisions as its stock price tumbled and losses mounted.

On April 1, 1993, Lou Gerstner became chair and CEO of IBM, after stints at RJR Nabisco and American Express, both quintessential marketing outfits. Many observers in and outside IBM doubted whether IBM’s first outsider could succeed, especially without a technology background. Some computer publications even polled their readers: “Do you think Lou Gerstner is the right man to lead IBM’s turnaround?”3

Gerstner soon identified IBM’s destructive practices, unnoticed when it was the technology leader with growing revenues. In R&D, IBM strove for the new and disdained outside technology. A classic sales-driven organization, sales reps pushed whatever R&D gave them. Over the years, many of IBM’s strengths, such as employee loyalty and a sales-driven culture, became its weaknesses. The company’s culture had grown insular, and the “IBM way” to do everything stifled experimentation. Worse, IBM’s people knew how computers worked but not what they did for customers. Gerstner, who had authorized purchases of IBM equipment at American Express, had a good understanding of this difference.

Gerstner made customer contact a priority, frequently going on the road himself to listen to customers without the IBM bureaucratic filter. He also wanted all employees to do the same. The IBM corporate office buildings symbolized the company’s insularity, bureaucracy, and lack of cost control. Gerstner saw the two IBM skyscrapers in New York and Chicago, designed by I. M. Pei and Mies van der Rohe respectively, as more suited to lawyers or investment bankers than an industrial giant like IBM. He emptied them and issued laptops so that employees could work from home or in the field.

What Gerstner heard was that customers lacked the expertise and the resources to integrate their hardware and software. They wanted solutions to their problems, but were stymied by the shortage of IT professionals and the rapid rate of technological change.

In response, Gerstner quashed plans to dismantle and sell IBM’s different businesses. IBM’s value, he argued, was in delivering vertically integrated products and services to the customer. IBM had products in every corner of the networking world—large-scale mainframe systems that hosted massive databases, high-performance servers, and application software. He changed IBM’s focus from selling hardware products to bundling hardware with software and service into a total technology solution. No other company could do what Team IBM could do.

In 1996, to demonstrate that services were now IBM’s strategic priority, Gerstner formed IBM Global Services (IGS) to deliver customer solutions by connecting and improving information flow among different businesses. By 2002, IGS had become a $36.4 billion business, a major contributor to IBM’s 2002 revenues of $81.3 billion and profits of $3.6 billion.

To communicate his new mandate, Gerstner’s speeches emphasized customer service and identifying what customers wanted. Accustomed to hearing about the “great IBM technology,” this message left many long-standing IBM employees cold. In response, Gerstner reasoned, “Technology changes much too quickly now for any company to build a sustainable competitive advantage on that basis alone.... [What matters is how] you help customers use technology.”

Transforming the Three Vs to Sell Solutions

IBM’s success has led other companies, including Cisco, Compaq, Sun Microsystems, and Unisys, to attempt similar transitions to selling solutions. Even Microsoft, the ultimate product company, claimed in a presentation to the banking industry, “Our goal is not to sell software products but to sell solutions to help the banking industry better serve its customers.”4

Despite some success, none of these imitators has managed the transformation as well as IBM. Why is the transition so challenging? Table 3-1 employs the three Vs model articulated in the previous chapter to show that becoming a solutions provider requires a significant modification of each element of the marketing concept.

The Products-to-Solutions Three Vs Transformation

| Product Focus | Solutions Focus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valued Customer | Almost all customers | Segment focus | |||

| Value Proposition | “Better” products with service | End-to-end solutions that reduce customer costs and risks or increase revenues | |||

| Value Network | |||||

| R&D | • | New technology focus | • | Customer problem focus | |

| • | Stand-alone products | • | Modular products | ||

| • | Proprietary products | • | Open, standards-based | ||

| Operations | • | In-house manufacturing of products | • | Partner with best providers and be product agnostic | |

| • | Limited supplychain complexity | • | Many interdependent partners requiring high coordination | ||

| Service | Cost center, bundled free with products | Profit center, unbundled from products | |||

| Marketing | • | Cost-plus product pricing | • | Value-based pricing | |

| • | Product sales | • | Multiyear service contracts | ||

| • | Salesperson as order taker | • | Salesperson as consultant | ||

| • | Geographical coverage | • | Industry experts | ||

| • | Volume-based commissions | • | Service-based commissions | ||

| Distribution | Products sold through many channels | Become a value-added reseller (VAR) | |||

Target Customers Who Will Pay for Solutions

In its 2000 annual report, the networking company 3Com stated, “There are products, and there are solutions. A product performs a function. A solution fulfills a human need. People want solutions.”5 Obviously, people prefer solutions rather than products—but not everyone will pay for them. The critical difference between customer needs and customer demands is that demands are needs that customers are able, and willing, to pay for. Since providing solutions requires customization and is therefore costly, a company aspiring to sell solutions must be meticulous in defining the valued customer for a solution.

Selecting the valued customer requires a thorough understanding of a solution’s value proposition. A solution involves more than simply bundling together related components and is not just a fancy name for cross-selling one’s own products and services. A true solution is defined by and designed around the customer’s need, not around an attempt to sell more of the supplier’s current products.6 Solution selling, therefore, requires a high degree of collaboration between the supplier and the customer in defining the customer’s need. After that, products and service components are integrated into a distinctive offering.

Given a set of products and competences, the customers and problems that will be served through solutions can be tightly specified. For example, IBM’s global services are focused on three areas: (1) front-end systems, to help redesign the customer interaction process through automation; (2) plumbing, which integrates systems since customers often have products from different vendors; and (3) outsourcing, where IBM runs the entire system. Because of the need for an in-depth understanding of the customer’s business operations and systems—which can be expensive and time-consuming to acquire—these services primarily target large customers.

To outsource an activity is usually a general management, or sometimes even a top management, decision. Therefore, the decision to purchase a solution is usually made by general managers rather than purchasing agents. Resistance is often encountered from the traditional buyer of “products,” the IT professionals, who fear that their jobs will be outsourced to IBM.

For example, in 2002, American Express signed a seven-year, $4 billion contract that shifted 2,000 IT professionals and computers to IBM.7 Rather than the standard outsourcing contract, American Express agreed to pay IBM only for the technology used every month. Consequently, American Express expects to save hundreds of millions of dollars over the life of the contract; and with IBM running the system, it expects to upgrade its technology five times faster.

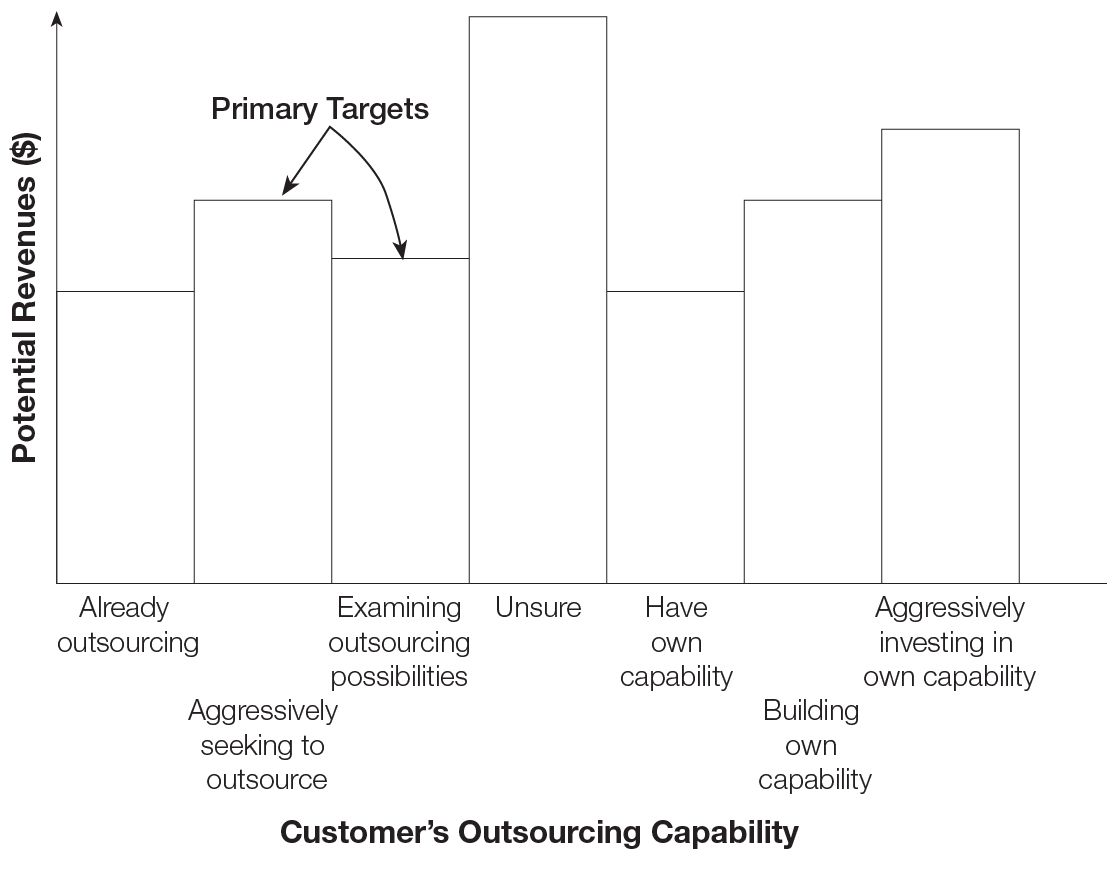

Customers rarely develop budgets for purchasing solutions. Therefore, the seller must convince the client’s top management that the firm needs a particular solution and that managers should budget for it. As shown in figure 3-1, the best prospects for purchasing a solution already want to outsource or are exploring possibilities. In contrast, customers who are already outsourcing have committed to a supplier and therefore may be more difficult to win. Solution selling also needs a salesperson different from the usual “order taker.” The solutions salesperson must be more of a “consultant,” able to interact with general managers, and capable of convincing the buyer to purchase a whole solution, not just a product or service.

Identifying Prospects for Solutions

Create Customer Value Through Three Types of Solutions

The “right” customer for a solution will derive value from faster deployment, seamless operations, a focus on core activities, fewer up-front costs, reduced support costs, and decreased use of internal resources. Solutions providers create customer value by: (a) helping customers increase revenues; (b) assuming customer risk and responsibility for part of the business; or (c) reducing customers’ total costs of consuming the product or service. While some powerful solutions tend to perform on all three dimensions, most solutions have one of these dimensions as the primary motivation.

Enhance Customer Revenues Through Solutions. Hendrix Voeders BV, an operating company of Nutreco, had an 8 percent market share of the Dutch animal feed market for pigs, poultry, sheep, cattle, and milk cows.8 While most companies competed on price, Hendrix Voeders priced its feed about 10 to 15 percent higher and competed instead on services. Its 150-person consulting force—separate from the sales force—provided services that helped deliver either an incremental animal weight gain of 5 to 10 percent or an increase of 4 to 5 percent in live births.

Delivering this productivity gain required a sophisticated data management system that allowed farmers and consultants to monitor the animals’ progress. Each animal was individually numbered and its feed consumption and weight gain was tracked daily. This precision allowed microadjustments in nutrients, medicine, and physical environment. For example, as a result of its sow monitoring system, Hendrix can help a sow that usually produces 18 to 24 piglets a year produce one or two more. The additional 10 percent price premium for Hendrix’s feed becomes relatively trivial.

Over the years, Hendrix Voeders has developed 1,500 feed products to meet animal nutritional needs through each phase of life. They have moved from being a supplier of bulk feed to providing a complete service to the farmer. For example, during an animal’s early growth phases, Hendrix can provide most of the essential supplies, from feed, milk substitutes, vitamins, and mineral mixes. At the other end of the cycle, it would arrange for the slaughter and sale of animals and the processing of meat. Its slogan? “If the farmer does well, Hendrix does well.”

Decrease Customer Risks Through Solutions. Quarries have traditionally used packaged explosives, usually sausageshaped, for blasting.9 To set up a blast, workers drill holes on the rock face over several days. On the day of the blast, they spend about five hours loading these holes with the packaged explosives, often racing to complete their work during the permitted hours. The process blasts rock far away from the site, then large backhoes and trucks harvest and transport it to the crusher, where the rock is broken into smaller, more uniform pieces. The rock is then stored according to grade, and is ready for sale to the customer.

Drilling and blasting costs were a significant portion of a quarry’s total operating costs. With strict controls on the storage and handling of explosives, quarries typically ordered just enough explosives for one blast, and had them delivered on blast day. The labor-intensive process allowed only a few quarries to compete in the industry, which is noted for large overcapacity.

A well-designed blast, however, could break the rock face into a pile of more uniform pieces—avoiding the large boulders that required secondary breakage before crushing—and would not throw rock more than thirty meters from the face, a danger as well as a waste of explosives. The rubble would then be much more easily harvested by the backhoes.

In 1985, ICI Explosives in Australia started supplying emulsion explosive in bulk from the back of a truck, rather than in the usual sausage packaging. After a customer placed an order, a Mobile Manufacturing Unit (MMU) containing intermediate chemicals arrived at the quarry, mixed the constituent chemicals on site, and delivered the resultant bulk emulsion explosive down predrilled blasting holes.

ICI also converted blasting from an empirical art to a precise science through laser profiling of the rock face and better blasting geometries. The improved consistency of the emulsion explosive and the detailed rock profiling reduced drilling time, thereby trimming overall drilling costs. Through better blast performance, ICI improved rock yield and reduced downstream processing costs.

ICI then began offering service contracts of “broken rock” to quarry customers, billing for their services based on the amount of broken rock of a certain defined size (as measured by the weighbridge), not for the amount of explosive supplied. The benefits for both the customer and ICI Explosives included:

- making the explosive part of an overall service, not a commodity;

- enabling ICI to make unconstrained deliveries to quarries since the component raw materials were nonexplosive until mixed; and

- giving the customer a fully charged set of blast holes, without excess explosive to store until the next blast.

Reduce Customer Costs Through Solutions. W.W. Grainger, the largest U.S. distributor of maintenance, repair, and operating (MRO) supplies with over five hundred thousand MRO products and sales of $5 billion, established Grainger Integrated Supply Operations (GISO) in 1995 in response to requests from customers (primarily manufacturing companies) for materials-management expertise and consulting.10 Grainger Integrated Supply Operations was aimed at businesses seeking to outsource their entire indirect materials management process, to reduce costs related to process, product, and inventory. Grainger employees work on-site, managing different services related to indirect materials for the clients, such as business process reengineering, inventory management, supply chain management, tool crib management, and information management.

At first, GISO was available only to customers who ordered a minimum of $1 million of product per location per year. For such customers, the savings resulting from Grainger managing the procurement process for indirect materials was substantial in absolute terms. Consequently, Grainger could more easily earn an adequate return on investment on large clients like AlliedSignal, American Airlines, General Motors, and Universal Studios. Over time, it has reduced the threshold for participation.

To be a solution seller, W.W. Grainger established a technological platform of extranets, intranets, and private networks that allow GISO employees to access twelve thousand suppliers and over five million products. They use these networks to communicate with suppliers and to evaluate prices, product availability, and technical data. They can thus reduce redundancy and improve efficiency in the supply chain, thereby cutting costs. Companies who outsource their entire MRO process to GISO report cost reductions of 20 percent, a 60 percent decrease in inventory, and process-cycle phase improvements of between 50 and 80 percent. Additionally, this means customer employees who normally managed these MRO processes are now free to focus on core business. GISO has documented that this increases employee productivity as well as reduces defects for the customer.

Solution-selling strategies that are based on reducing customer costs take a holistic view of total customer costs rather than focusing simply on product costs. W.W. Grainger does not compete by reducing the prices of the products that the customer purchases. Instead, it focuses on lowering the customer’s total costs (for example, products, handling, inventory, waste, and labor) of consuming MRO supplies.

Similarly, IBM promises significant costs reduction to those clients who sign multiyear contracts and outsource most of their IT operations to IBM. For example, in March 2002, IBM won a $500 million contract to provide the IT backbone for Nestlé’s Globe project. 11 Nestlé, the world’s biggest food company, is planning to centralize more than one hundred IT centers around the world into just five, as part of a plan to cut costs by $1.8 billion over five years. IBM will provide servers, storage systems, and database software for the five Globe data centers: two in Bussigny, Switzerland, and others in Sydney, Frankfurt, and Phoenix.

The IBM contract is part of Nestlé’s attempt to set up a common IT platform that will allow it to consolidate and standardize its global business processes without losing its decentralized management structure. Over the years, Nestlé has duplicated IT and marketing support functions in most of the countries it operates. One of the main aims of the Globe project is to harmonize supplier, customer, and product data for Nestlé worldwide.

The Globe project, launched by CEO Peter Brabeck, could boost Nestlé’s EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) by more than a quarter to 15.2 percent by 2006, for a compound growth in earnings per share of 15.1 percent between 2003 and 2006.

Design Products for Service

To support the new value proposition, top management must reevaluate almost every component of the value network. As a product-driven organization, IBM was focused on selling products, with services being a tactical weapon employed as needed to close sales. As a solution-driven company, service is the “product” that the customer is purchasing and the products are bundled in as needed.

For IBM to become a true solutions provider meant that its historical pride in developing the best quality stand-alone products became less critical for success. Instead, companies wishing to sell solutions have to concentrate on helping customers solve problems by integrating different products. Hence, solution sellers focus on product modularity and develop “plug-and-play” products that can easily integrate with their own, complementary, and even competitors’ products.

To deliver on the promise that the system will perform seamlessly, companies must design products with ease-of-service in mind, since the solutions provider often supervises the system’s operation on site. 12 If the products are expensive to service, then the contracts may become unprofitable. This is in stark contrast to the product-driven company, where servicing and replacement parts can generate considerable profits.

Select an Appropriate Product-Agnostic Posture

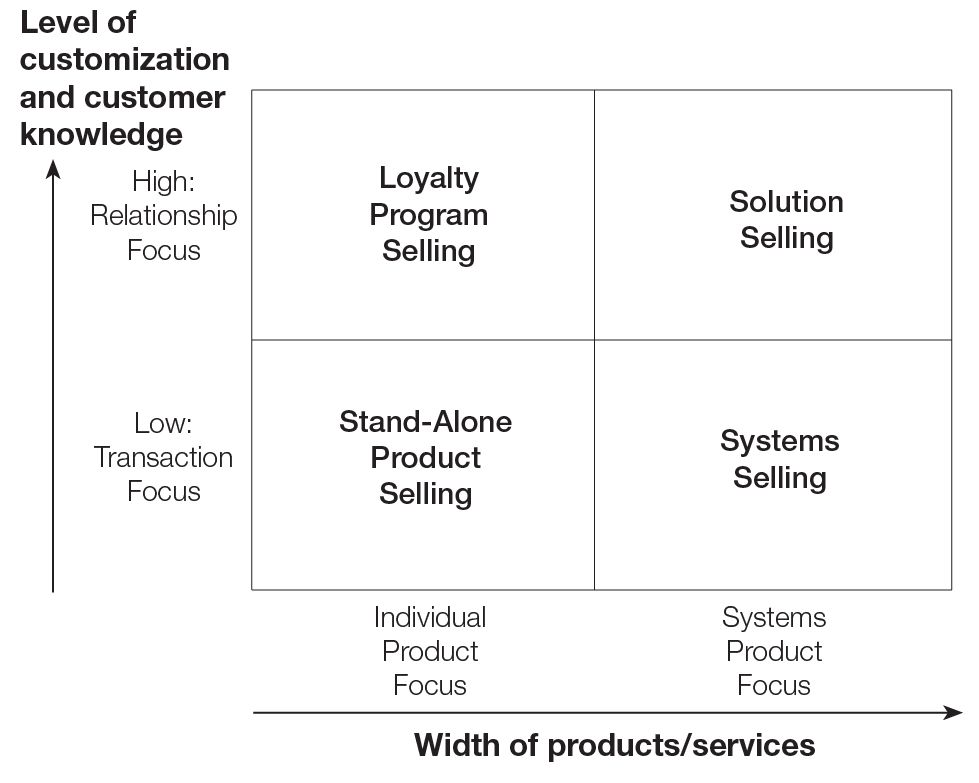

IBM and other companies often combine their previously incompatible products and services to create seamlessly operating systems that they market as “solutions.” They then look for customers with problems that might fit their proprietary solution. In contrast to such systems selling, real solution selling involves working with a customer to uncover their problems and then designing a customized solution (see figure 3-2). The pre- and post-sales efforts are considerable and require a strong relationship with the customer.

No company can maintain a technological advantage in all the products necessary to complete solutions. In addition, customers may have their own brand preferences, based on legacy systems. For proud product companies, the most gut-wrenching change is to become product agnostic, allowing the customer to specify any brand of hardware, even competitors, as part of its solution.

Solution-Selling Matrix

A company that recommends its own products even when they are not optimal for a particular application or customer reverts to selling products and systems rather than solutions. For example, a London department store chain that features home furnishings decided that consumers desired solutions to their home decoration problems. Therefore, the store deployed personal shopping assistants to help consumers. Unfortunately, the personal shopping assistants could recommend only furnishings in the store, which greatly reduced the assistants’ efficacy.

Those people assigned to the solutions-selling unit in product-oriented companies often must choose between product logic and solution logic.13 In client interactions, they need to assume a consultant identity to act in the client’s best interest first, and in the product division’s second. However, product divisions often expect the solutions unit to maintain a staff identity, demonstrating loyalty to the company brands. If the product logic dominates the solution logic, then the firm loses its ability and credibility to provide customer-centric solutions.

Product-Agnostic IBM? IBM has attempted to make IGS hardware agnostic by blending technology from different sources like Sun or Hewlett-Packard and recommending the best for each application. In 1999, all IBM executives signed a “business partner charter” in which they pledged to bundle IBM products and services with competitors’ superior products. Today, IBM boasts the “industry’s most extensive Business Partner network”—seventy-two strategic software partners, including SAP and Siebel Systems. Its marketing and distribution muscle make it an attractive integrator for smaller software companies.

Partnering allows IGS to access more potential customers and provide a more complete palette of services to existing customers. Bob Timpson, general manager of IBM developer relations, summed up the partner rationale: “In the current world, you can’t have just your own hardware, software, and sales force. You have to be part of a larger ecosystem.”14 Of course, one must always raise questions about brand integrity and performance guarantees on competitors’ products.

Product agnosticism has lent credibility to IBM as a technology expert. As a solutions provider, IBM actively discussed how customers could leverage technology to improve their operations, innovation, and distribution channels. By blending technology from different sources, IBM built systems that responded to specific customer business needs. This product-agnostic customer focus has built trust between IBM and its customers.

Becoming a solutions provider is a journey, not a destination. IGS is still not truly agnostic regarding other hardware and software brands. If the customer wants a different platform, IGS will provide it, but reluctantly. Furthermore, IBM will keep its pledge to bundle products from competitors that are better, but only if that competitor is an approved IBM Business Partner, which is not an easy status to achieve. To help, IBM has instituted an incentive system for its consultants whereby their bonuses depend less on selling IBM products and more on meeting goals within the services business.

Does Having Great Products Hinder Solution Selling? Following IBM’s success, Hewlett-Packard (HP) has made at least three unsuccessful attempts to adopt a similar customer solutions strategy by integrating its vast range of products and undoubted technical capabilities.15 Hewlett-Packard’s merger with Compaq is its latest crack at becoming a more effective competitor against IBM.

Besides its highly decentralized culture, part of the problem for HP is its great engineering background and all the wonderful products it has created as a result of that. A culture of great engineering can become a handicap in making the transformation to solutions, since the company often falls in love with its products instead of its customers and their problems. In fact, one may argue that it is preferable for a solutions provider not to have proprietary products as it forces the firm to create customer value purely through integration.

Accenture, formerly Andersen Consulting, is an example of an information technology solutions provider with no products of its own in the classic sense. Instead, Accenture consultants look at the customer, map out the customer’s processes, and then reengineer and automate them. The consultants spend their time understanding the client and its work practices instead of trying to sell products. When the time comes to select the hardware, Accenture can be relatively neutral. In fact, most customers do not specify a particular brand of hardware. Since usually more than one box can do the same function, Accenture buys from the most appropriate vendor for the deal. Accenture’s only products are concepts and methodologies—this makes it particularly powerful as a solutions provider.

Price to Capture the Value of Solutions

Unlike products, setting the appropriate price for a solution is difficult, especially since no two solutions are identical. Even if the solution is identical, its value to different customers may differ considerably. The price must be delicately balanced between the value of the solution to the customer and the cost of providing it for the supplier.16 If the price is too high, the customer may decide to buy individual components and develop their own solution. If the price is too low, then the supplier will not be adequately compensated for the effort that went into delivering it.

To avoid pricing solutions too low, the valued customer and value proposition must be clear. The value of the solution for the customer must be greater than the cost of its discrete components. The value should not lie in a quantity discount achieved by consolidating sales with one vendor. Solutions providers earn greater margins because the price of the whole package exceeds the prices of the discrete components.

Part of the value created for the customer accrues from the different pricing options offered by the solutions provider. Since most solutions deliver value over time, customers may differ considerably in how they pay for the value created based on their financial and risk profile. The options vary from a one-time, up-front payment (turnkey solution), a series of payments as the value is delivered (pay per use or milestone payments), a recurring monthly or yearly charge (periodic payments), or even revenuesharing and equity participation.17 In addition, there may be all types of fees for service, maintenance, operating, license, and consulting. These pricing strategies may be used separately or in combination and are a far cry from the dollars per box, pound, or ton mentality in most business markets.

Move from Free to Paid Services

There are several different ways to perceive the role of services in companies. Traditionally, in product companies, services are bundled free and are therefore a cost center. For example, companies often ask Cisco to provide information on becoming more e-business oriented and Cisco does not charge any fees for such advice. It believes that the equipment orders that result from sharing their expertise far outweigh the cost of providing such consultancy services.18

At IBM in the 1960s and 1970s, the margins on mainframes were so high that IBM could bundle all its services in them. As it became a solutions provider, IBM started unbundling the services and charging individually for them. One of its most successful strategies has been pursuing large multiyear service contracts, which has become a model for competitors such as HP.19

As the Cisco and IBM examples demonstrate, companies take different positions along the following continuum regarding the role of services: (1) provided free in support of products; (2) partial cost recovery; (3) full cost recovery; (4) independent profit center in support of products; or (5) an independent business unit that supports and utilizes competitors’ products.20 Solutions providers fall into the final category. Companies usually do not jump from free services to solutions; instead they tend to go through one or more of the intermediate stages.

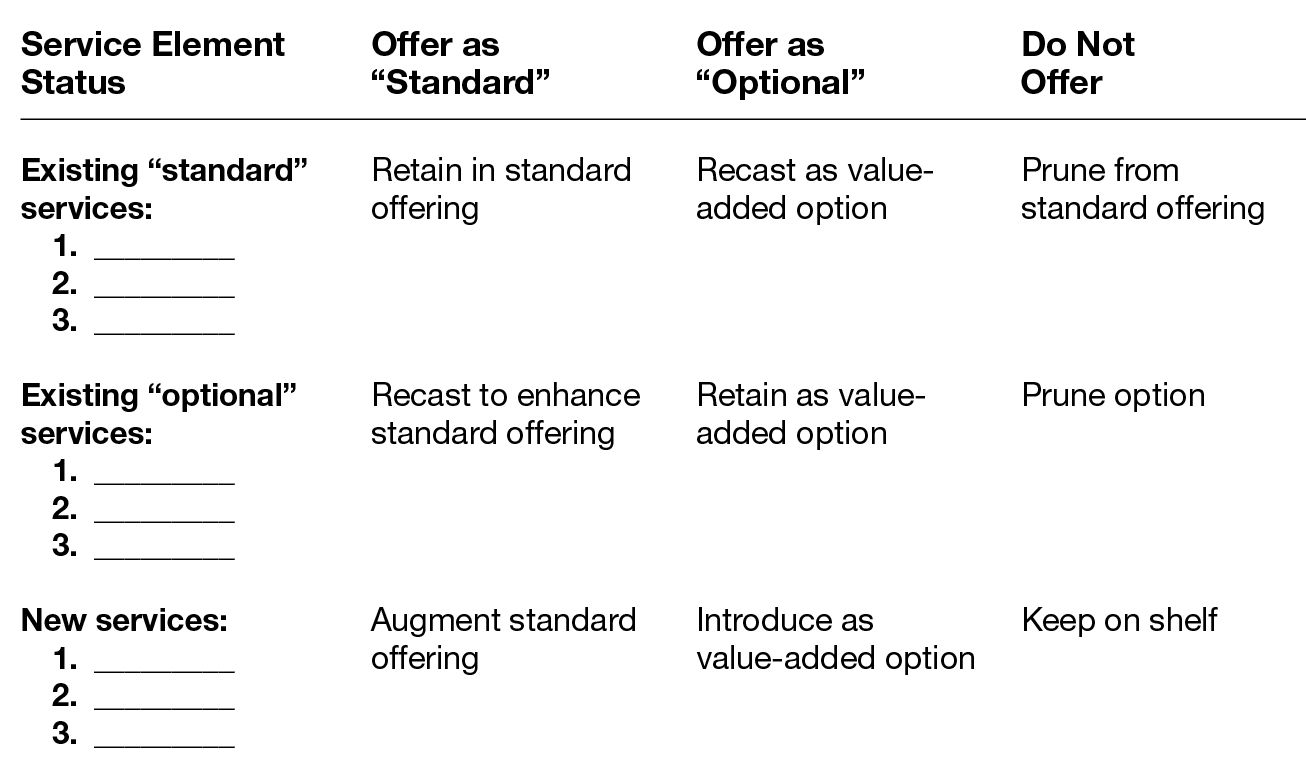

Making the transition from free to paid services is difficult because companies struggle to make customers realize the value and the costs of the free services that they receive. Part of the difficulty lies in the fact that all customers do not equally value these free services. Some customers consume significant amounts of free services while others barely use them. Consequently, charging for these previously free services is an effective way to segment customers, as heavy users of services now have to pay for them whereas those customers who do not consume services receive more competitive prices. Yet, convincing heavy users to start paying for services is not easy, as Internet business models—which are based on providing free services to end users in exchange for ancillary revenue streams such as advertising (Yahoo!, for example) —have discovered.21 The best way to approach this problem is by using the matrix in table 3-2 developed by two professors, James Anderson and James Narus. The process begins by selecting a segment and then listing under each heading in the first column the services currently offered to that segment as a standard (that is, for free), those offered as options for additional fees, and the new services that the company is contemplating offering. For each standard, optional, or potential new service, one should then ask whether this service should be: (a) offered for free (that is, “standard”) because most customers place a value on it; (b) offered as an option because only some customers place a value on it; or (c) removed from the offer because very few customers place any value on it or the cost of providing it outstrips the value for customers. Once this decision has been made, the matrix suggests how each service should be managed.

Service Offering Matrix

Source: Adapted from James C. Anderson and James A. Narus, Business Market Management: Understanding, Creating, and Delivering Value (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999), 176. Reprinted by permission of Pearson Education, Inc., Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Given the difficulty of persuading customers to pay for existing free services, it is easier to begin the process by innovating and developing new services, which are offered for a fee as a way of conditioning customers into paying for services. Simultaneously, one can send phantom invoices (usually with the words “do not pay” ) to unprofitable customers whenever they consume a free service so that they begin perceiving the value thereof. Companies that find ways to communicate value can convert freeloaders of services into paying customers over time. Finally, one can also develop two versions of a service: a free one and an enhanced version for a premium. For example, Hotmail accounts with limited functionality are free, whereas paid accounts come with full functionality.

For many product companies, services now account for a significant, fast-growing portion of their revenues.22 Of Otis Elevator’s $5 billion revenues, two-thirds come from service and maintenance fees. ABB Service manages more than 100 large, full-service contracts worldwide for maintaining its or competitors’ equipment.

Build Solution-Selling Capabilities

Effective solution selling requires developing new capabilities and significant investments of scarce resources such as time, people, and money. The lack of these requirements has stalled many firms in their transition from selling products to providing solutions.

Change the Mind-Set to Take Responsibility for Customer Outcomes

An agonizing change in mind-set is necessary in order to transition to solution selling. In a product-driven company, everything begins and ends with the existing product and its functions, and a constant search for new applications and new customers. If the product is not ideal for some customers or applications, then the firm either adds a new product feature or develops a new product.23 Regardless, the company can solve only those problems that correspond with the company’s own products.24 In contrast, a solution-driven company starts with a customer problem and guarantees the desired customer outcome, which usually requires taking responsibility for the entire process at the customer’s site.

For example, instead of selling gallons of paint to car manufacturers, one paint supplier manages the painting process and charges the automakers a fixed fee per painted car. In the earlier approach, the more paint that was wasted in the car manufacturing process, the greater the profits for the supplier since it meant that it sold more paint. But after taking over the painting process, waste in the painting process meant lower profits for the paint supplier since paint was now a cost in its capacity as a solution provider.

Map the Entire Customer Process

Solution sellers often create value by sparing the customer the hassle and cost of dealing with multiple suppliers, as well as by reducing the ordeal of integrating the components and services. To understand the value of seamless operations, for example, consider the following scenario of a customer attempting to resolve a problem. The software provider says the problem is in the hardware, the hardware provider says the problem lies with the network connection, the network support company says the problem is the phone line, while the telephone company says the problem is with the software. Solutions providers instead provide one contact point.

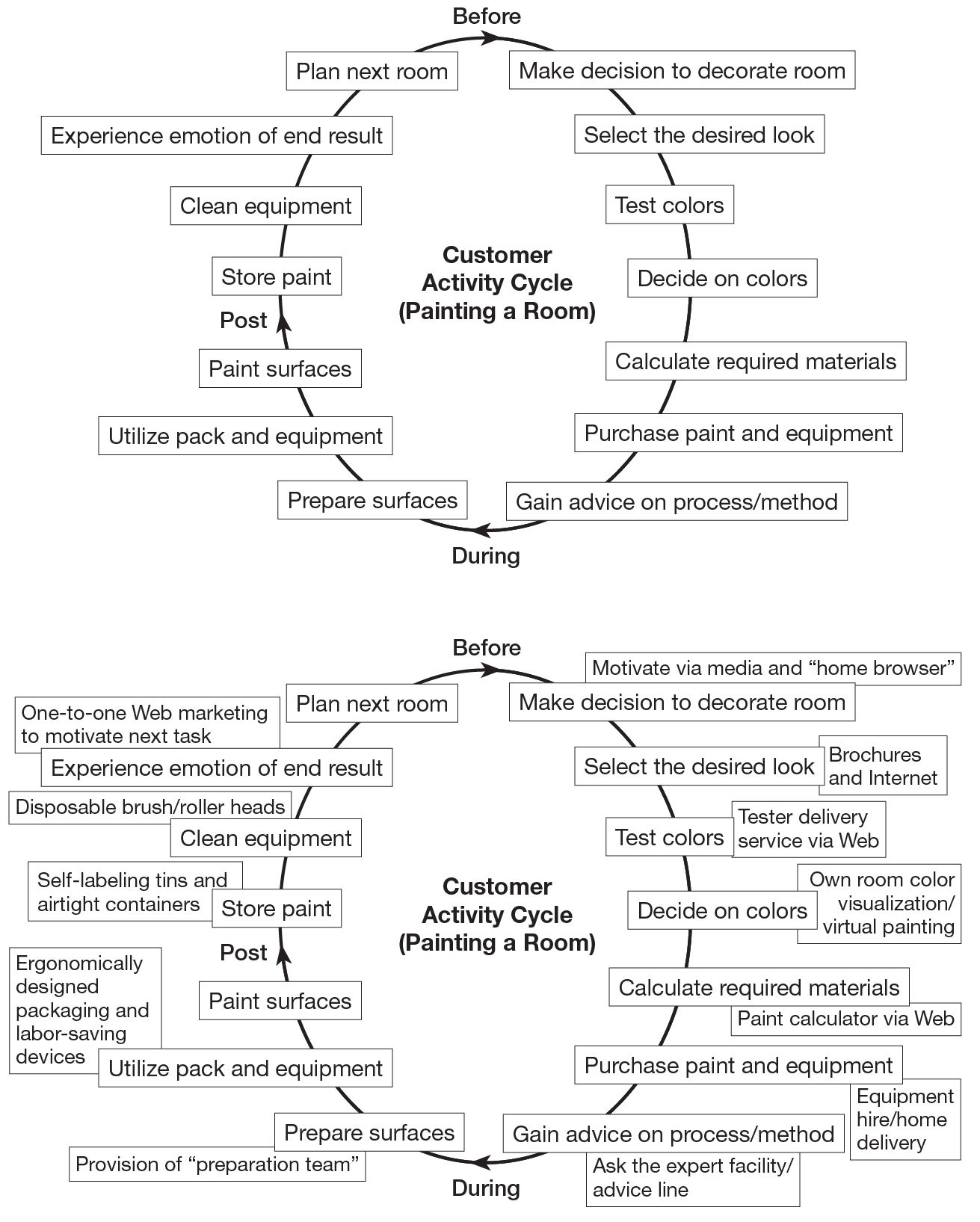

Providing a seamless solution for the customer requires mapping out the entire business process for the customer and developing a solution that makes it easier for the customer to consume the product. The seller’s process must fit with the customer’s process, and each customer may have a different process. Rather than focus on the product, the entire customer activity cycle related to consuming the product must be articulated.25 As an example, figure 3-3 elaborates the process that a do-it-yourself painter must go through to paint a room.

Assess Customer Total Cost

As the Hendrix-Voeders, ICI Explosives, and W.W. Grainger examples demonstrate, solution sellers must thoroughly understand the operating economics of their customers. In addition to taking responsibility for the customer’s outcome and mapping the customer’s process end to end, the solution seller must document the customer’s total costs of consuming the product.

Articulating the total costs requires outlining all the different acquisition costs (price, prepurchase evaluation, shopping time, paper work, expedition of the order, mistakes in order, and travel costs), possession costs (interest, taxes and insurance, storage, installations, handling, shrinkage, obsolescence, and quality control), and usage costs (downtime, parts and supplies, training, user labor, product longevity, replacement, and disposal).26 Discussing this with a customer widens their focus from just the product price.

Consider Airbus’s success over Boeing. Airbus can provide a fleet of different aircraft with the same cockpit design and similar flying traits.27 Such similitude lowers costs since Airbus users do not need to retrain pilots whenever they switch aircraft, and airlines can schedule pilots to fly various planes. While Boeing can offer extremely attractive prices, the initial capital cost of a plane represents only a small part of the cost of each flight hour.

C. C. Tung, chairman of Orient Overseas Container Line, remarks, “We are training our staff to function more as logistics consultants than service providers . . . to avoid competing on price alone.... [Transportation] is a relatively small part of the our major customers’ total logistics expenditures, so we are . . . helping them in other ways, such as reducing interest costs through minimum stocking [and] improving cash flow through speedy and error free documentation.”28

Educate Customers About Total Costs

Unfortunately, customers are often unaware of the operating economics of their own business processes. Consequently, the solution seller must educate the customer. For example, Douwe Egberts, part of Sara Lee, has developed a freshly brewed coffee solution called Cafitesse for professional food service operators in Europe. A modular system incorporates high-speed brewing (a cappuccino in nine seconds) and reduced cleaning and maintenance, while producing little waste in terms of coffee, filters, or coffee remains. The coffee-brewing market, as one would expect, is extremely price sensitive, and focus is often on the price per kilogram of coffee. The coffee used in the Cafitesse solution does not compare favorably on a price per kilo basis but coffee by itself accounts for only about 20 to 30 percent (up to 40 percent in some cases) of the total costs of making a cup of coffee. The remaining elements are usually forgotten by, or hidden from, the customer, leading to erroneous cost comparisons between different coffee brewing solutions.

To help educate the customer, Douwe Egberts developed an extensive and transparent Excel spreadsheet. It calculates the current cost per cup for the customer using their existing solution and then compares that with the cost per cup using the Cafitesse solution. The comparison considers many different elements including cleaning time, depreciation, filters, power, water usage, waste of coffee brewed, and so on—elements that all are part of a cup of coffee, no matter how the customer chooses to brew it. The high-speed and lower-waste features of Cafitesse help reduce the cost per cup. As an example of waste, consider that 98.5 percent of a “normal” cup of coffee is water. If 20 percent of the brewed coffee is wasted when using a conventional coffee system, both coffee and water are important elements in the waste equation. By supplying the customer with a system that reduces waste, pricing turns into something more than just “per kilo” prices.

Customers are often surprised when confronted with the costs of their existing brewing method. The spreadsheet makes them more open to listening to Cafitesse’s arguments. Looking at the total cost per cup of coffee, where Cafitesse compares rather favorably, changes the conversation with the customer from price to taste.

Similarly, W.W. Grainger conducts a detailed analysis for large companies to demonstrate that in consuming indirect materials, process costs account for approximately 70 percent of a product’s total cost. One of its advertisements—“It took seven people to buy this hammer. The hammer costs $17. Their time costs $100”—helps educate purchasing agents that most of the monetary savings do not lie in pushing the supplier to lower product costs.

Develop Knowledge Banks

Solution selling is information intensive. To sell solutions, a company must have extensive information on each customer and their business processes, as well as the ability to slice the data in multiple ways. For example, as part of its customer relationship management (CRM) process, IBM maintains up-to-date estimates of the needs of its thousand largest customers.29 These estimates include both current requirements as well as projections of their future needs. Customers are then ranked according to their growth rates and estimated lifetime value to IBM.

Often, companies sell a high level of customized information bundled around the original product. By becoming an expert in the consumption process through benchmarking across customers, the seller can deliver knowledge on how best to apply the product. The knowledge that Hendrix Voeders, IBM, ICI Explosives, and W.W. Grainger ultimately sell to their customers becomes the true distinguishing—and constantly growing, if well managed—core competence of the organization. The more a firm uses it, the more powerful it grows in the marketplace, and competitors cannot easily copy it.

To sell solutions effectively, a company must have a system that provides companywide access to otherwise isolated pools of expertise. IBM is investing in an online inventory of its knowledge so that the IBM intranet can function as a collaborative portal for its solution sellers. One feature is an “expertise locator” which could, for example, help an employee find a software engineer who can build a Linux database.

Transforming the Organization for Solution Selling

Solution selling clearly has critical implications for the organization. If the organization does not morph, then the solutions strategy will atrophy, especially in large companies. Consider IBM’s transformation.

Corporate Fault Zones

Effective solution selling requires the salesperson to quickly diagnose the critical issues facing the client and then craft a customized and complete solution that fits the customer’s requirements. To succeed, the salesperson must have a keen insight into their company’s capabilities, as well as the ability to deeply understand the business of the customer. This may mean hiring outsiders, perhaps from the customer’s industry, who have an extensive knowledge of the customer’s business processes and costs.

IBM realized the challenge that a salesperson faced in selling a computer to a bank one day, to a retailer the next day, and to an oil and gas company on the following day. The only way a salesperson could accomplish this was by being an expert in the products rather than being an expert on customer problems. If the sales force were to evolve from being order takers to becoming consultants to customers, they needed to become industry experts.

If the IBM salesperson sold an IT solution to a large multinational customer, then delivery required mobilizing several country and product divisions. In a sense, the solutions provider guaranteed that many parts of many different units would collaborate.30 But the seats of power in IBM belonged to product chiefs and especially the geographic heads. If you were the president of IBM France, it was like an ambassadorship. You had a huge organization with lots of staff work, secretaries, and bureaucracy. Thus, IBM’s organizational structure impeded providing solutions to customers, while system integrators, who put together products from different vendors to solve customer problems, were gaining influence at IBM’s expense. In response, Gerstner designated fourteen industry sectors for IBM to dominate (for example, financial services and retailing) and appointed individuals to lead each one.

Many of the new IBM industry heads were outsiders selected on the basis of having the personality and power to go head-to-head with the IBM geographic and product chiefs. The product and country heads became internal suppliers to these industry heads as the latter attempted to create customer solutions. A few country managers resisted reporting to the industry heads and some of them ultimately left the firm. Creating solutions for large multinational clients required coordinated efforts that cut across multiple products and countries. The firm reorganized the geographically assigned sales force along industry lines and developed new coordinating processes, such as transfer pricing to allow product units to sell internally, and structures, like strong regional leadership, to allocate resources to solutions.

The Transition Process

While it looks revolutionary in its implications, the change from a product company to a solutions company is an evolutionary process. It takes time and effort to convert product customers into solution buyers. During this period, the current as well as the future business models must be managed. Managing on these two levels presents a complex management challenge.

The traditional product- and country-based business units must continue to perform while the new team-based organization responsible for customer solutions floats on top of them. Dedicated customer solution teams will draw together elements from different business units to deliver on particular projects. During the transition, the previous clear-cut accountability, hierarchy, lines of authority, and dedicated resources will be under stress from the new business units, which are organized around fluid teams and opportunities, and managed by project owners who lack direct control over the necessary resources.31

Employees who will be providing customer solutions need expertise from relevant product groups, industry consultants, and country specialists to implement integrated solutions. For them, the company must function as a portfolio of resources, not business units.32 But the traditional proprietors of these resources—the product and country managers—will view such sharing of scarce resources as unrequited costs and worse, as they lose their best customers to solutions teams.33 Compensation committees must review incentive systems so that compensation plans for top managers stress contributions to the company, relative to their business units.

Transformational Leadership

To transition to solutions selling, companies need the type of transformational leadership that Lou Gerstner provided at IBM. Gerstner cut costs, overhauled the culture, and instilled the customer-centric mind-set. While revenues had been consistently high, IBM’s internal fiefdoms made the costs of doing business even higher. Gerstner reportedly remarked when he first took over, “We’re making $64 billion a year. By far, the most money spent in the information technology business is being spent with us. The problem is that it’s costing us $69 billion to do it. ”34

Gerstner’s transformational leadership played several important roles in IBM’s turnaround. First, he brought his external viewpoints to an inward-looking, myopic culture. A former IBM customer, he understood market and industry issues enough to make IBM a much better partner to its customers. By focusing on customers rather than technology, he amassed a vital intellectual power over the rest of the organization.

Second, Gerstner realized that IBM needed senior management with no loyalty to IBM’s past winning concepts and practices. He sought experts who could understand customers and cut costs.35 Breaking precedent, he chose his vice president of marketing and vice president of communications from outside IBM, and then hired Chrysler’s Jerry York as CFO to cut costs in a tough environment.

Third, since Gerstner appreciated IBM’s brand strength and potential impact on the market and marketing process, he kept the company intact rather than divest underperforming units. Keeping the company intact was the single most valuable decision he made for shareholders.

Fourth, as an ex-McKinsey consultant, Gerstner recognized the importance of aligning structure with strategy and worked tirelessly to harmonize the various IBM units and minimize the turf wars. Gerstner’s early successes endeared him to the IBM troops fairly rapidly.

Samuel J. Palmisano, IBM’s current CEO, remarked, “The DNA of the IBM company is what it always stood for. But get rid of the bad in the DNA—rigid behavior, starched white shirts, straw hats, company songs . . . that caused us to become insular, focused on ourselves. Beating up your colleagues was more important than winning in the marketplace. Lou [Gerstner] did a lot to knock all that down.”36

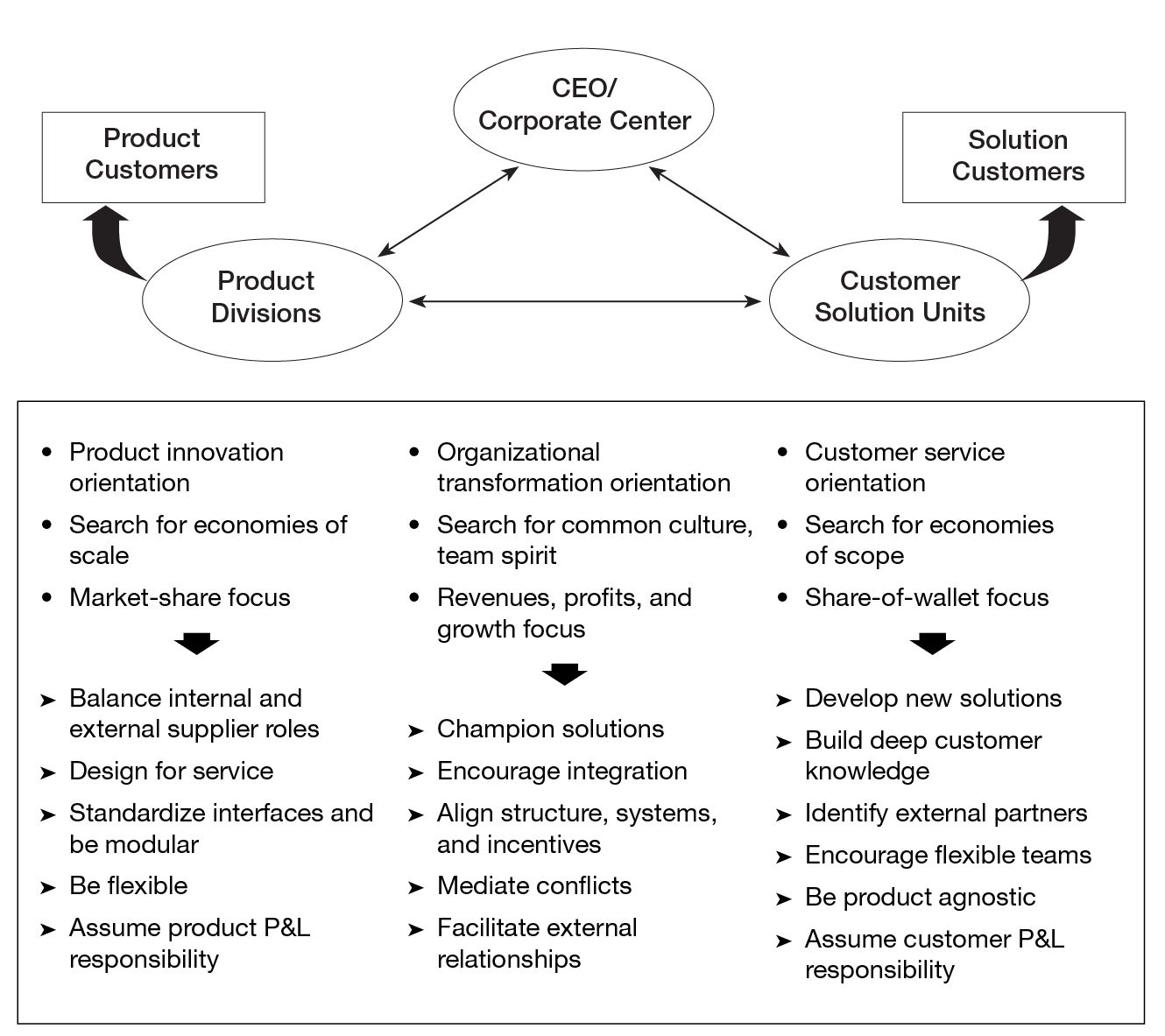

FIGURE 3 - 4

A Solutions Organization

Source: Adapted from Nathaniel W. Foote, Jay R. Galbraith, Quentin Hope, and Danny Miller, “Making Solutions the Answer,” McKinsey Quarterly 3 (2001): 84–93.

With help from the corporate center, CEOs play an important role in championing the case for customer solutions. They must help with the collaboration process, to iron out the conflicts that rise to their attention. They may have to sponsor initiatives to change the resource allocation process within the company. Projects need to be ranked to ensure that the most valuable resources are chasing the most valuable solution-selling opportunities. Figure 3-4 summarizes the organizational architecture supportive of solution selling.

Solutions Checklist

Valued Customer and Value Proposition

- Have we defined criteria to identify customers who are willing to pay for solutions?

- What is our primary value proposition to solution customers—increase revenues, lower total costs, or reduce risk?

- Do we offer customers various payment options such as pay per use, revenue, or cost savings sharing?

- Do we guarantee customer outcomes instead of product performance?

- Are we product agnostic?

- Do we truly make money off integration (charge more than the prices of the products bundled in the solution)?

Solution Capabilities

- Are we focused on developing modular products that interface easily with our own and competitors’ products?

- Do we have the capability of guaranteeing system performance at customer sites?

Conclusion

Jack Welch of General Electric noted: “The winners will be those who deliver solutions from the users’ point of view. That is a big part of Marketing’s job.” However, as a company attempts to transform itself from a seller of products to a provider of customer solutions, it will observe that many of its strengths, such as a decentralized organization, great technology, and strong product divisions, become precisely those things that stop the firm from making an effective transition.

- Have we developed effective tools to assess customer value?

- Have our salespeople developed consulting skills and deep customer industry knowledge?

- Can we articulate customers’ total costs and operating economics?

- Do we have the industry’s best customer information and knowledge bank?

- Do we have strong project management skills?

Organizing for Solutions

- Do our product and country organizations support solution selling?

- Is the CEO championing the solutions initiative?

- Have we developed effective processes to allocate resources to solution projects?

- Does the organizational incentive system support the delivery of solutions to customers?

- How good are our coordinating mechanisms (for example, transfer pricing) for serving solutions to customers?

Developing customer solutions entails having a thorough understanding of the customer activity cycle and customer total costs. Information on the differential economic benefits that each customer will receive from the solution provided is critical. To deliver the customer solution requires a broader skill set, the risk profile to take greater responsibility for performance at the customer site, more flexible operations and organization, and the ability to manage numerous partnerships with suppliers and competitors. Additionally, capturing the value of solutions delivered to customers requires offering flexible pricing options. The box “Solutions Checklist” provides a checklist for solutions. Considerable investments are needed to capture the learning acquired from each project. A proprietary database that is continuously updated with data on each customer, implementation process learning, and solution technology is essential.

The successful solutions company is a networked company. It has the ability to integrate diverse production skills and multiple streams of technology from a variety of companies, including itself. It must quickly see new opportunities to solve customer problems and exploit them through flexible structures and declining transactions costs. The ideal solutions provider has an organization that is people-, knowledge-, and process-intensive but asset-light. Its focus is on knowledge—learning about customers, collaborative learning with partners, and learning to leverage network partners’ resources and competences. Instead of filling capacity or assets, it focuses on using knowledge to leverage its primary asset—people. This is what allows it to earn higher margins than its competitors.

To achieve all of this requires, most of all, a change in mind-set. Without a focused effort from the top of the organization, the move to selling solutions is doomed to succumb to the overwhelming corporate inertia that haunts most large organizations. For the transformation to succeed, someone, most likely the CEO, must stake his or her career on it.