FOUR

From Declining to Growing Distribution Channels

Let us keep the cannibals in the family.

AS A NEW CHANNEL, the Internet complicated distribution not only by facilitating the delivery of digital goods and services like news and music but also by enabling dynamically priced transactions for just about any physical good or service—among perfect strangers. Electronic marketplaces have proliferated for business-to-business (B2B) sales (for example, FreeMarkets), business-to-consumer (B2C) retail, resale, and referrals (for example, Amazon), and consumer-to-consumer (C2C) resale and services (for example, eBay).

The Internet is but one of several technologies affecting distribution, and new channels inevitably startle managers at large, established firms. Should they rapidly develop new competences and exploit these emerging channels to reach new customers, often at lower costs, or should they wait until the format matures? Will they cannibalize current revenues or jeopardize long-standing reseller partnerships?

Such incumbent dithering allows upstarts like Amazon, Charles Schwab, Dell, Direct Line, easyJet, and IKEA to seize advantage and disrupt industry leaders through channel inflexions, or disruptions that overturn industry channel structure, in industries such as entertainment, financial services, communications, computing, publishing, software, and travel. Charles Schwab has developed the financial supermarket model by concentrating on distribution in a traditionally vertically integrated industry. Citigroup has aggressively shifted customers and transactions to ATM machines, while Direct Line has become the largest automobile insurance company in the United Kingdom by using telephonebased selling. Dell and easyJet have developed cost-efficient business models based on selling directly to consumers while disintermediating traditional retailers and travel agents, respectively. Michael O’Leary, CEO of Ryanair, notes, “Four years ago we sold 60 percent . . . through travel agents, who charged us about 9 percent of the ticket price. Then computerized reservations added about another 6 percent. So we were paying about 15 percent for distribution. Today, 96 percent of our sales are sold across Ryanair.com, and the cost is about a cent per ticket.”1

Observing the success of these new entrants, incumbents are finally realizing the strategic role of distribution and the need to adjust their channel strategies. Under pressure to generate top-line growth in a tough economic and competitive environment, senior executives cannot overlook innovative channels that reach new segments and significantly cut costs.

But channel migration from the old to the new rarely happens without turmoil and top management support. Line marketing managers will simply not challenge entrenched internal and external constituencies without top management’s support. Reconfiguring channels demands a CEO like O’Leary: “British Airways says you can’t upset the travel agents.... Screw the travel agents! . . . What have they done for passengers over the years?”2

Channel Migration Strategies

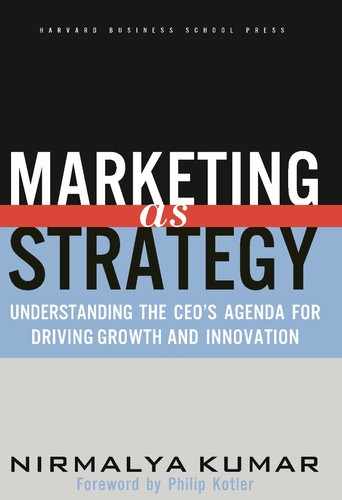

When a new distribution channel emerges, managers must ask two essential questions: (1) To what extent does the new channel complement or replace existing industry distribution channels? (2) To what extent does the new channel enhance or devalue our existing capabilities and value network? The answers should help pinpoint the necessary channel migration strategy, the level of internal resistance, and the external channel conflict that one should anticipate, as well as provide insight into the migration process (see figure 4-1).

Channel Migration Strategies

Replacement Versus Complementary Effects

Supermarkets that displaced “mom-and-pop” stores in the United States illustrate the replacement effects of new distribution channels.3 The supermarket’s value proposition of a better assortment, one-stop shopping, and substantially lower prices for a little more travel surpassed that of mom-and-pop stores. Consequently, the absolute number of mom-and-pops and their relative market share both declined.

In contrast, television and home video extended the distribution channels of the motion picture industry. When television first appeared in the 1950s, Hollywood studio market values fell dramatically. The same happened with cinema companies when home video first appeared. In each instance, managers and analysts overlooked two important issues.

First, the value proposition of the new distribution channel (television and home video) was different from, but not superior to, the existing channel (cinema theatres). Home video, for example, offers greater assortment, time flexibility, informality, and lower prices, whereas cinemas are venues for a “date” or “an evening out.” The two distribution channels have clearly delineated value propositions for distinct customer usage segments and can therefore coexist.

Second, home video allowed consumers to watch movies when tired, dressed down, wanting solitude, or homebound by babies or illness, or when cinemas were closed or no longer running a particular film. Television and video expanded the market for motion pictures and provided substantial additional streams of revenues for the industry. Producers no longer relied solely on cinema revenues to break even. For example, in 2002, U.S. box office revenues were $10.1 billion, but combined sales and rental of VHS tapes and DVD discs exceeded $25 billion.4

Whether a new distribution channel complements or displaces existing distribution channels highlights the nature of channel migration. In replacements, the existing customer segments buy from the new channels of distribution and abandon the existing channels. In contrast, complementary distribution channels open up new segments of customers or new value propositions for existing products. Cannibalization, channel conflict, and resistance to change obviously occur more in replacement situations.

Replacement channels force incumbents to abandon existing channels and focus on new channels of distribution. The ability to purchase airline tickets or book hotel and car reservations over the Internet will not likely increase the number of vacations or business trips consumed. Instead, with the necessary information accessible online, many customers will simply not need a travel agent. No wonder three hundred storefront travel agents are closing per month, and the share of U.S. domestic airline reservations booked through independent travel agents has declined from 80 percent to less than 50 percent.

Replacement effects also obligate managers to determine which channels and segments are affected. For example, leisure consumers for airline travel are migrating faster to Internet channels than business travelers. Based on the firm’s competitive position in each segment, one may decide to accelerate the migration, as easyJet does by offering discounts to customers who book on the Web, or decelerate by refusing to accommodate the new channel.

In contrast, complementary effects compel companies to move certain types of transactions and customers to the new channel of distribution. New channels add to the existing value network without substantially lowering the value of existing distribution outlets. Marketers must communicate these economics to distribution members who may irrationally fear any new outlet. Sharing independent market research demonstrating the complementary effects works especially well in reducing channel member anxiety.

Turning Core Capabilities into Core Rigidities

The emergence of a new type of distribution channel usually generates considerable excitement as companies see the potential for increased coverage, lowered costs, and/or greater control. Unfortunately, innovative new distribution channels also aggravate industry incumbents. Established companies often fear that new, especially radically new, distribution channels will harm them by obsolescing competences, devaluing their distribution network assets, ossifying their core capabilities, and eroding their industry leadership positions. To illustrate these repercussions, let us examine the channel transitions in the PC industry.

Channel Migration in the PC Industry. In 1981, almost 80 percent of personal computer sales were through a combination of a direct sales force serving the large accounts and full-service PC dealers reaching the rest. Currently, direct sales and PC dealers account for less than 40 percent of the industry sales with the remainder flowing through a multiplicity of channels including value-added resellers (VARs), direct response pioneered by Dell, mass merchandisers dominated by Wal-Mart, warehouse clubs like Price Club/Costco, consumer electronic superstores populated by Best Buy and Circuit City, computer superstores led by CompUSA, and office product superstores such as Staples. In addition, there are numerous Internet operations of brick-and-mortar and pure play retailers. During the intervening years, channel transitions have played a major role in determining the changing fortunes of PC manufacturers such as Compaq, Dell, and IBM.

COMPAQ VERSUS DELL. Today, the worldwide PC market leaders are Compaq and Dell. However, as table 4-1 demonstrates, the business models of the two companies differ significantly. Compaq has a value network typical of branded products:

Business Models of Dell Versus Compaq

| Dell | Compaq | |

|---|---|---|

| Value Customer | Knowledgeable customer buying multiple units | Multiple customer segments with varied needs |

| Value Proposition | Customer PC at competitive price | “Brand” with quality image |

| Value Network | ||

| R&D | Limited | Considerable |

| Manufacturing | Flexible assembly, cost disadvantage | High-speed, low-variety, low-cost manufacturing system |

| Supply Chain | Made-to-order; one week, primarily component inventory | Made-to-stock; one month, primarily finished-product inventory |

| Marketing | Moderate sales response advertising | Expensive brand advertising |

| Sales and Distribution | Direct | Primarily through third-party resellers |

relatively high R&D expenditures; low-cost, low-variety, largerun manufacturing systems; one-month finished products inventory; and third-party resellers. In the early 1990s—when IBM, with its large direct sales force, was ambivalent about third-party resellers—Compaq dedicated itself to PC sales through resellers, thereby endearing it to resellers, whose subsequent push catapulted Compaq into market leadership in 1992.

Dell primarily targeted corporate accounts but with built-to-order, customized PCs at reasonable prices. It invented a radically different value network combining minimal R&D expenditures, made-to-order, flexible manufacturing systems (which give Dell a slight manufacturing cost disadvantage compared to Compaq), one-week parts inventory, and an efficient direct distribution system. In the early 1990s, this direct distribution system took orders through toll-free telephone numbers and delivered through various courier services.

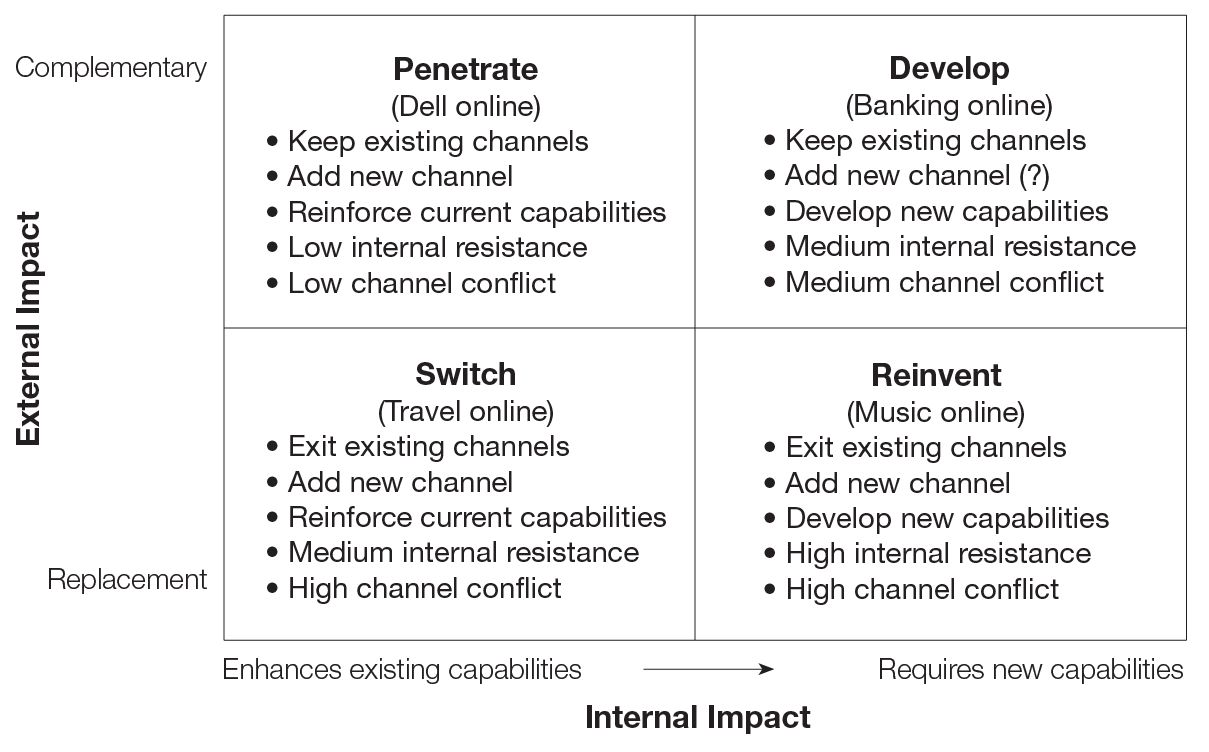

DELL’S RETAIL EXPERIENCE. As the value curves in figure 4-2 indicate, the value proposition of serving customers through Dell Direct differs from that through retail stores. In 1991, to reach those small business customers and individual consumers who preferred to shop at retail outlets, Dell decided to expand its distribution to retailers such as Business Depot in Canada; CompUSA, Sam’s Club, and Staples in the United States and Mexico; and PC World in the United Kingdom.5 However, unlike the customization option available through the Dell Direct channel, since selling through retail stores required Dell to build for inventory, only a limited number of preset PC configurations could be offered in the indirect channel. Despite this limitation, channel expansion to retail stores brought immediate and impressive sales gains for Dell as revenues rose from about $900 million in 1991 to more than $2.8 billion in 1993.

Unfortunately, the sales gains through the retail channels did not result in additional profits. Dell’s internal cost of selling fell from 14 percent in the direct channel to 10 percent in the indirect channel as retailers took responsibility for some channel functions. However, this did not fully offset the 12 percent margin that retailers had to be given for their sales efforts. As a result, it was 8 percent more expensive for Dell to sell through indirect channels. Given that its operating income was only 5 percent in the Dell Direct channel, it was losing 3 percent in the indirect channels. And the more volume Dell pushed through the retail channels, the more money it lost. In 1993, Dell posted its first loss of $36 million. By mid-1994, Dell decided to exit the retail channel and concentrate on direct distribution. This decision turned profits around to $149 million in 1994.

Value Curves: Dell Direct Versus Retail

Beyond the economics, Dell sidelined many of its core capabilities and advantages when sales went through retail. Michael Dell explained,

Our direct model . . . turns inventory 12 times, while our competitors who sell through retail only turn their inventory 6 times. Even though customization increases our costs by 5%, we [can] get a 15% price premium because of the upgrades and added features. But for the standard configurations we offered through retail, we [could not] get any premium in the market.... Compaq, not us, got a 10% price advantage.6

COMPAQ, DELL, AND INTERNET DISTRIBUTION. In the mid-1990s, Compaq and Dell explored how to exploit the Internet. What made the Internet so exciting was the opportunity to have a one-to-one dialogue with the customer (interactive capacity) and then to respond with a unique, customized offer (responsive capacity).Thanks to its value network, Dell exploited the unique features of the Internet, and sales through the Internet were a natural extension of the “Dell Direct Model.” It launched its Web site in July 1996.

Compaq, on the other hand, struggled to exploit the Internet, because to do so would force it to customize PCs and bypass dealers. However, delivering customized products at competitive prices with high-volume, low-variety manufacturing systems is tricky. How could Compaq promote sales through the Internet without upsetting its resellers and jeopardizing its historically strong relationships with them?

Compaq lagged Dell by almost three years in adopting direct sales through the Internet. To limit direct competition, Compaq initially designed a new line of PCs, Prosignia, for direct online sales. When retailers objected, it offered this line through retail channels as well. The Internet channel had turned Compaq’s core competences and distribution network assets—low-cost manufacturing systems and strong relationships with third-party resellers—into core rigidities. By 1999, Dell overtook Compaq as the U.S. market leader with online PC sales of $30 million daily.

Regardless of whether a new channel complements or displaces existing distribution channels at an industry level, it will likely affect the core competences and distribution network assets of existing players in different ways. Therein lies a large part of the disruptive nature of new distribution channels: New channels may help some companies leverage their core competences and distribution assets, while it hinders other companies within the same industry. How competences and assets are affected depends on how a company competes within an industry. But the need to develop new capabilities usually generates considerable internal resistance as it devalues the power of those within the organization who run the existing value network.

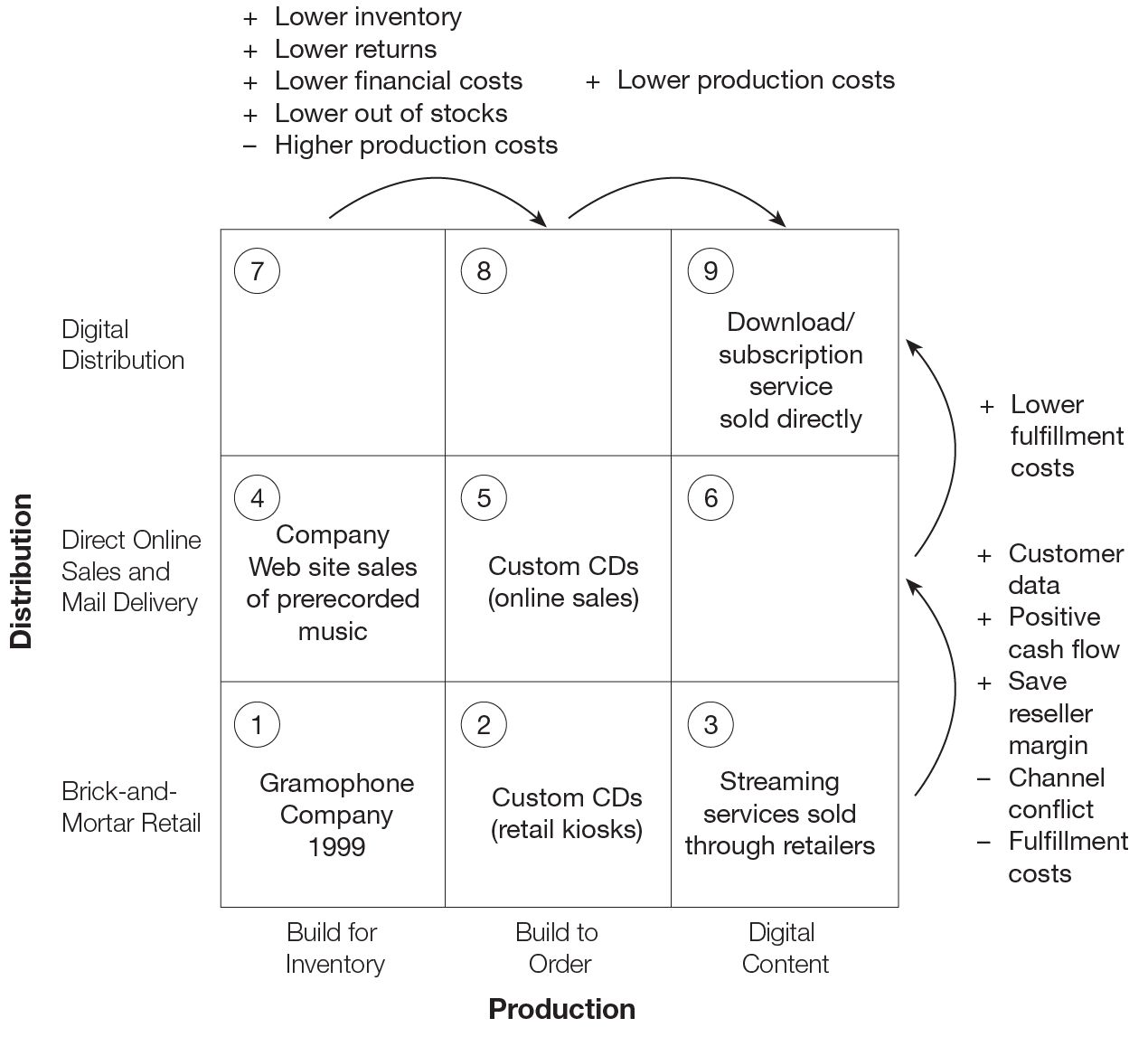

The Reinvention of Music Distribution Business Models. As illustrated in figure 4-1, the most difficult channel migration strategy is to reinvent distribution channels. Reinvention is necessary in the face of both replacement effects and the need to develop new capabilities. In such cases, the importance of business model transformation cannot be overestimated. New distribution channels that are convenient and attractive from the consumer’s perspective can languish without profitable business models. This situation currently pervades online distribution of digital products like movies, music, games, books, and software. In particular, online distribution of music is having a potentially dramatic, and some would say destructive, impact on existing industry business models.

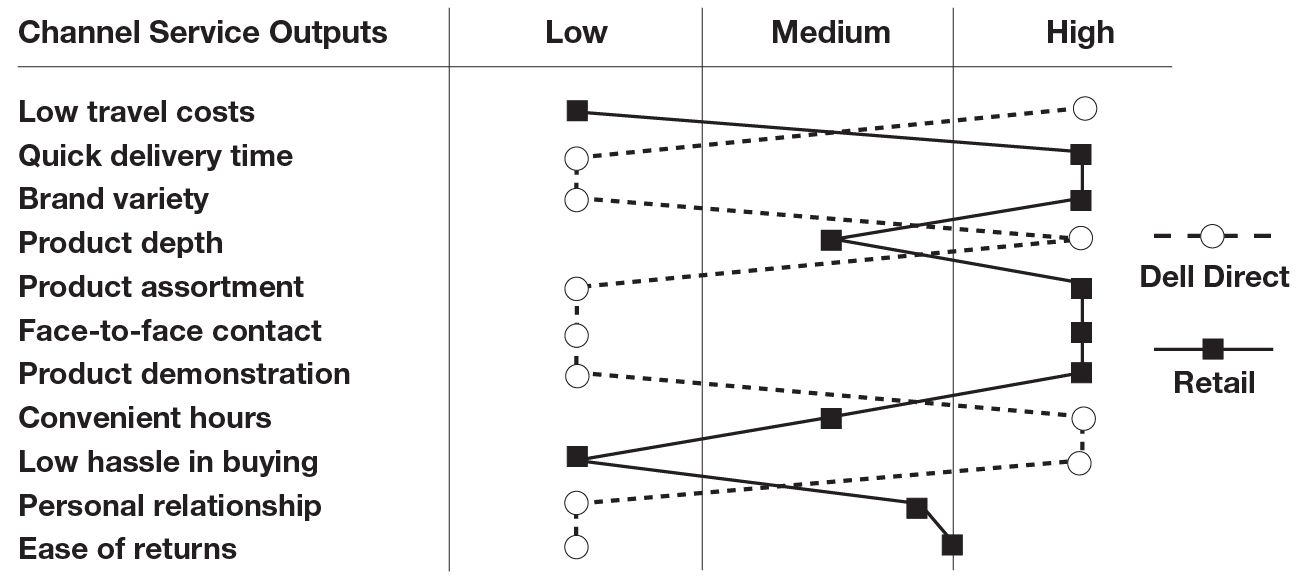

THE MUSIC INDUSTRY COST STRUCTURE. The average prerecorded music CD sells in the retail store for about fifteen dollars. Figure 4-3 attempts to break down its cost structure. Two things are particularly relevant when examining the industry’s traditional value chain. First, distribution-related costs account for a relatively high proportion, 40 to 50 percent, of the total price. Second, predicting which products will be a “hit” is a relatively difficult proposition for the industry. So music companies guarantee retailers the right to return unsold product for full credit. Some 15 to 25 percent of the product comes back. The absolute costs of handling these returns, included in distribution and logistics, are enormous.

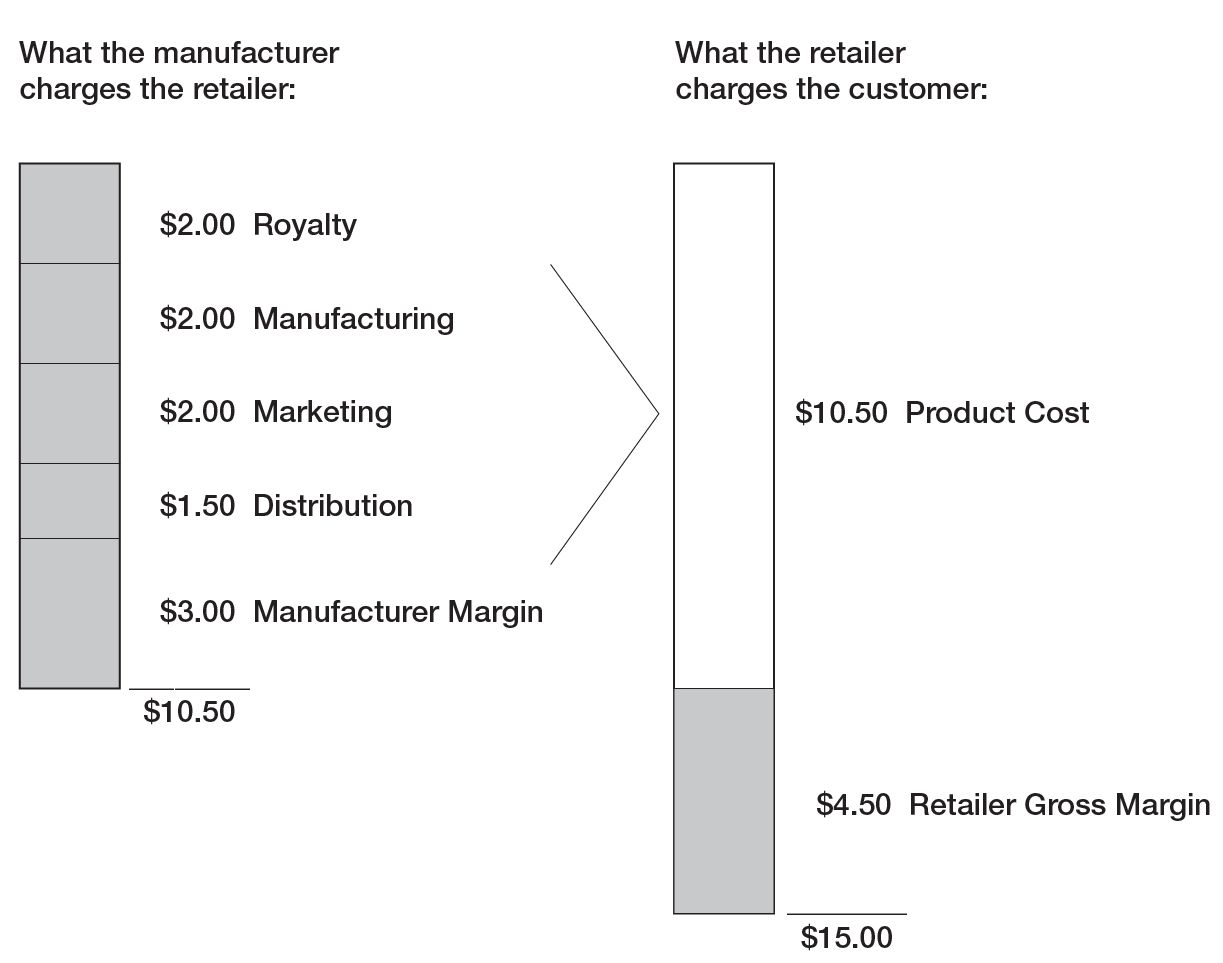

GRAMOPHONE COMPANY OF INDIA. Given the cost structure of the CDs, and a similar situation in the book publishing industry, online sales is a rather attractive opportunity for these manufacturers. Consider the Gramophone Company of India, the largest music publisher in India .7 Gramophone owns the rights to forty-five thousand albums or 50 percent of all Indian music ever recorded. However, it is only economically viable for the company to rerelease an old album and keep it in print if the demand justifies a production run of five thousand copies. As a result, between years 1995 and 2000, only 17 percent of the album catalog was being exploited, or in industry jargon, was in print. Sales were through brick-and-mortar retailers with about 15 percent of sales being returned as unsold stock. In terms of distribution, Gramophone Company, like other music companies, was squarely in the lower left-hand corner (box 1) of the distribution matrix of figure 4-4.

Cost Breakdown for a Compact Disc

The emergence of the Internet brought with it the opportunity to sell directly to consumers and move to box 4. Since the Indian music retail industry is highly fragmented, mostly populated by mom-and-pop stores, channel conflict was not a major concern. For the music manufacturer, selling online had the benefits of not having to pay the retailer’s margin, greater customer knowledge, and positive working capital. Since the mailing costs for CDs and cassettes were not high and consumers would pay some additional shipping costs, the fulfillment costs did not overwhelm the advantages of online sales. Expanding into direct online sales was easy.

Online Music Distribution Opportunity Matrix

A special division called HamaraCD investigated customized CDs where consumers could select songs from the manufacturer’s Web site (box 5) or at a retail kiosk (box 2). The manufacturing costs of a custom CD were somewhat higher than a prerecorded CD but the additional benefits of no inventory, fewer returns, and allowing the entire catalog to be offered (no out-of-stock situation) more than compensated for this. Furthermore, consumers place a 50 percent higher value on custom CDs, allowing the manufacturer to charge a higher price.

THE SEARCH FOR A DIGITAL DISTRIBUTION MODEL. Broadband Internet has opened up an entirely new, completely digital form of music distribution. By allowing customers to directly download or stream music off a server, both production and distribution costs decline dramatically (boxes 3 and 9). Suddenly, the music, an information product, is freed from the tyranny of the plastic CD box, a physical product, and the problems that come with managing physical manufacturing and supply chains. Unfortunately, worried about piracy and faced with the need to develop new business models, music companies were too slow to exploit digital distribution.

Time is now running out for music companies to find that new business model. The global recording industry has shrunk for the sixth consecutive year (down from 785 million CDs and cassettes in 2000 to 681 million in 2002), while the sales of recordable CDs have more than doubled between 1999 and 2001.8 In fact, 2001 was the first year when more blank CDs than recorded CDs were sold.9 Artist David Bowie observed, “The absolute transformation of everything that we ever thought about music will take place within ten years, and nothing is going to be able to stop it . . . you’d better be prepared for doing a lot of touring because that’s really the only unique situation that’s going to be left.” 10

While music executives and artists launched lawsuits against online music swapping, Apple Computer launched the iTunes music store in 2002. iTunes allows consumers to download music at 99 cents per track and burn it onto CDs or transfer it among three specified computers. In the first two months, customers downloaded over 5 million songs, proving that a simple, reasonably priced online service can attract consumers. When broadband is readily accessible and reliable, a subscription service that streams music to consumers anywhere, anytime becomes a viable business model. For the price of perhaps one CD a month, companies could offer unlimited music to consumers off a central server. This capability could change the music business from a packaged goods industry to an electronic distribution industry. However, to succeed requires transforming the existing industry business model.

The Channel Migration Process

Channel transitions, even for the better, are usually traumatic and difficult to reverse. Therefore, prior to launching into channel migration, it is prudent to do one’s homework. Successful channel migration is composed of the following four-step process.

Step 1: Conduct a Distribution Strategy Audit of Existing Channels

Given the delicate interdependence that exists between the new and existing distribution channels, a company should assess how well it is performing in its current channels prior to entering any new ones. Why rush into new channels without understanding and developing strategies to resolve conflicts in the existing distribution network? Unfortunately, many companies see the new channels as a way to overcome or avoid problems. For example, consumer packaged goods firms initially thought that the Internet would allow them to bypass the powerful traditional retailers that controlled access to consumers.

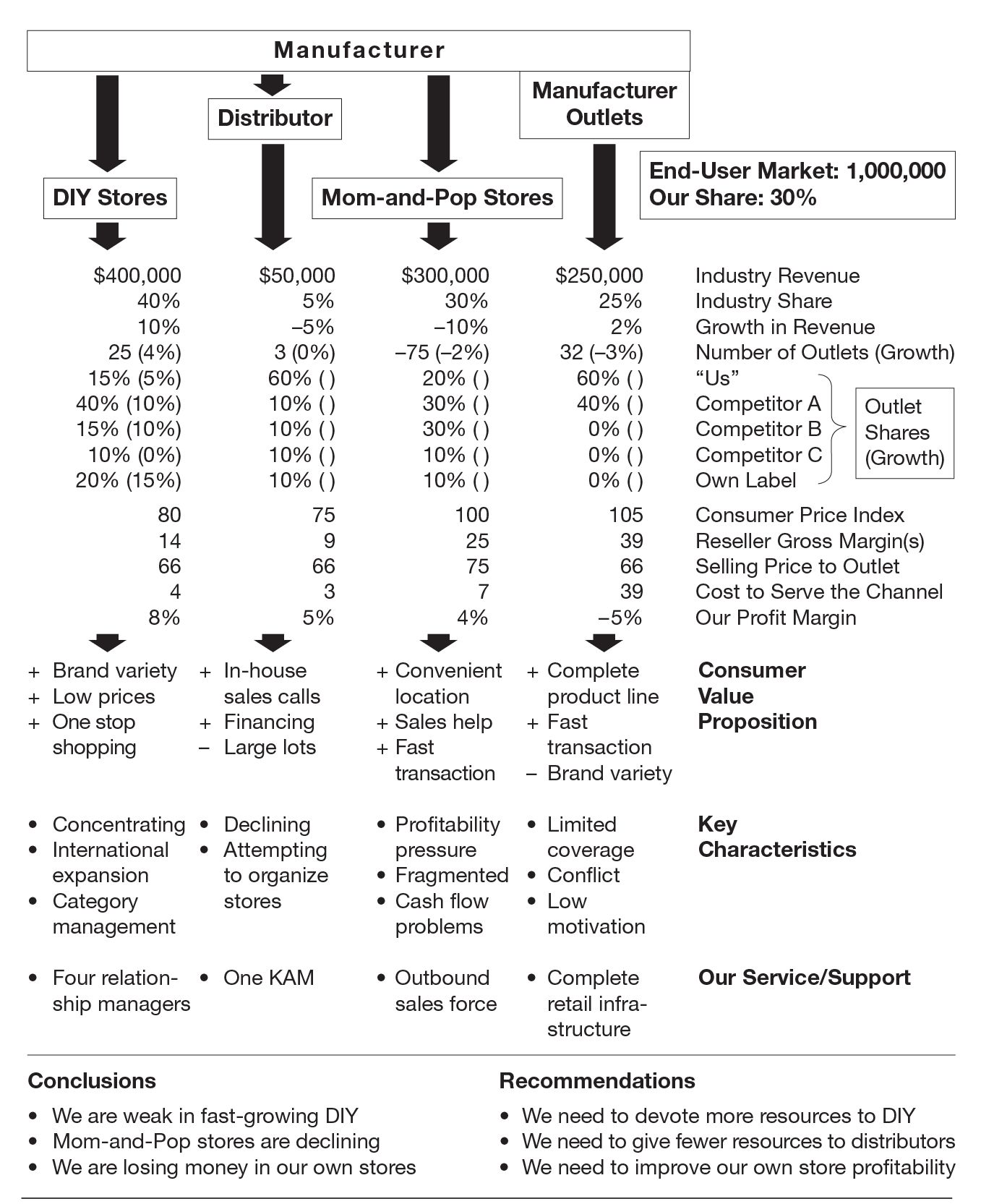

Figure 4-5 demonstrates my distribution strategy audit tool that many companies have effectively used. It assesses the company’s distribution network from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives.

To fully exploit this tool, companies must have implemented some level of activity-based costing (ABC). Activity-based costing helps get more precise estimates of the cost of serving through each channel. In one fast-moving consumer goods company in Brazil, the managers complained constantly about the price pressure that the large retailers were exerting. However, on conducting a relatively simple ABC analysis, they discovered that the manufacturer profitability was highest in sales through large retailers. In fact, the manufacturer was actually losing money on sales through mom-and-pop stores despite the fact that these stores were paying the highest prices. The difference was in the manufacturer’s cost to serve to the two channels. The mom-and-pop stores had to be supported with high levels of outbound sales efforts and service. In contrast, the large retailers were assigned only key account managers, purchased in large volumes, did not permit any in-store manufacturer help, and had their own inbound logistics service.

Distribution Strategy Audit: Consumer Durable Goods Firm, Do-It-Yourself Sector

Step 2: Articulate the Strategic Logic for Channel Migration

A well-articulated strategic logic for entering a new or emerging channel of distribution is the bedrock of any channel migration decision. The following six questions are helpful in evaluating the opportunity presented by the new distribution channel.11

- How attractive is the value proposition that the new distribution channel offers to our target segments?

- Is the proportion of our target segment attracted to the new channel large enough to demand our attention?

- Do we have a differentiated value proposition or an operational advantage in serving customers through the new channel?

- Is our cost structure and value network optimized to serve customers through the new channel?

- What can and will competition do with the new channel?

- How will the new distribution channel change consumer channel preferences and strategies of existing channel members?

To understand the attractiveness of a new channel of distribution, managers should plot the value curves for each of the channels, ideally with some market research data from consumers. The value curves usually reveal that no “best” channel of distribution truly exists. Rather, each channel has its strengths and weaknesses, and a segment for which it is best suited. For example, in figure 4-2, Dell Direct is better for patient price buyers whereas retail is better for those who want to test products and get local service.

The first three questions look relatively obvious but new channel enthusiasts often miss them. Much of the misplaced optimism about the Internet resulted from such management zeal. Consider Priceline.com, a company that sells flights, hotel rooms, and rents cars on its Web site.12 Priceline.com allows customers to name their own price for a flight on a particular date and then either accepts or declines the offer. Customers cannot specify the airline or the time of departure. Consumers benefit by getting very low prices in return for sacrificing some flexibility, and airlines benefit by selling excess capacity at prices above marginal costs. In 1999, Priceline.com decided to extend its model to groceries.

Despite the widespread belief at the time that many products would eventually be sold online, the grocery venture failed. To buy an airline ticket at a discount, once or twice a year, is worth waiting for acceptance of one’s offer. Moreover, most major airline seats and services are identical; any airline will do. But in groceries, consumers treasure certain brands and replacements are not considered equal. Furthermore, computing a desirable discount price for a different basket of desired products on each purchase occasion was too much of a hassle. Given the high marginal costs and the ability to inventory most groceries, major brand manufacturers had little incentive to participate. The target segment and the related value proposition were too small.

Exploit Online Channels When Network Effects Exist. Now that the Internet hype is over, one can take a more dispassionate look at where online selling can create value for consumers and marketers. The Internet’s most important attribute is that it dramatically reduces transaction costs, or the cost of connecting people and businesses to one another. It adds the most value when connecting large numbers of consumers, sometimes referred to as P2P (person to person) or network effects. It’s no wonder that eBay, the online auction site, is one of the most successful Internet business ideas. eBay’s business model would not be as effective or as efficient without the Internet.

Other profitable businesses that capitalize on network effects of the Internet are massive multiplayer games (MMPG) and various matchmaking services. One example is Sony’s EverQuest, where more than 432,000 subscribers pay $12.95 per month to indulge in a medieval role-playing fantasy against other online gamers.13 Similarly, the Korean NCSoft has four million customers who play games such as Lineage that can involve hundreds of thousands of people at the same time. No more having to be a lonely kid!

Given the costs of fulfillment, it is hard to create profitable online models for physical goods where the costs of shipping are relatively high compared to the price of the product. Furthermore, there are many products that consumers wish to see, touch, and feel, and where online selling will have a limited impact. However, even here if network effects matter, such as when sending gifts to family and friends who live far away, online sales can be significant. Thus, while online sales in 2002 accounted for only 2.5 percent of the U.S. retail industry, U.S. consumers spent more than 17 percent of their year-end holiday shopping budgets online.14

Consider Cost and Competitive Moves. The importance of the fourth question on cost structure and value network is emphasized by the earlier example of the differential effects of channel transitions on Compaq and Dell. The online music sales example also underlined the importance of examining the effects of new distribution models on costs and value chains.

What competition can and will do is an important consideration in developing strategy toward the new distribution channels. Voices within the organization will lobby for letting competitors move first, since early entrants usually bear the brunt of the backlash from existing channels. For example, when Delta initiated online selling and reduced travel agent commissions, many independent travel agents vowed to boycott them.

Insights from game theory in economics, which models interactions among independent players, can be particularly useful here. For example, suppose a manufacturer is considering direct online sales to consumers. It must balance the potential for additional sales and margins with the risk of upsetting its existing dealers. The optimal approach depends on two factors: (1) what management expects the major competitor to do with online sales and (2) the level of online sales expected.15 Both of these require judgments since no one can accurately predict the level of sales through a new channel in the initial stages.

If online sales turn out to be small, then the firm should stay out of this channel and hope that its competitor initiates such sales. The competitor would suffer channel repercussions, and the firm could exploit this backlash to enhance its own position with existing channels. But if online sales turn out to be significant, then the competitor would gain important first-mover advantage. Of course, one must consider a whole host of other factors, such as the speed of change. If online sales take off slowly, then the second mover may still enter without significant volume loss while letting the first mover work out all the political and technological kinks.

Finally, distribution innovations such as the Internet change consumer shopping patterns. The ideal service outputs demanded by consumers from the distribution channel evolve over time, especially regarding channel discontinuities. Managers should periodically ask several key questions: (1) How well are existing channels serving the needs of existing customer segments? (2) How will consumer preferences for channels change, potentially warranting a different segmentation? (3) How will the strategies of all channel members and of competitors change? (4) How should we alter our distribution channel strategy to enhance our value network?

Step 3: Mobilize Support for Channel Migration

A strong strategic logic for channel migration can fail in the face of the powerful inertia that plagues most companies. Consider the example of Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company in the United States in 1992.16 Goodyear had historically sold its tires to the replacement market through a network of wholly owned outlets and independent dealers. Goodyear did not distribute through service stations, mass merchandisers such as Sears and Wal-Mart, or warehouse clubs like Sam’s Club. Its main competitor, Michelin, distributed aggressively through all channels.

Unfortunately, Goodyear’s independent dealers were increasingly unable to compete against the buying power of warehouse clubs and mass merchandisers. As a result, an increasing share of the branded tire market migrated to these clubs and merchandisers. Since Goodyear was absent in the latter two channels, it had large coverage gaps in the branded tires marketplace. The decision of whether Goodyear should sell tires through Sears, Sam’s Club, or Wal-Mart faced remarkable internal and external resistance.

The point is that new channels threaten both the sales volumes in the existing channel and the managers within the company who are responsible for them. Often the compensation of these executives is linked to the volumes in existing channels. But beyond the compensation issues, a rich personal network of relationships emerges between managers and their counterparts in existing channels. These friendships and associated levels of personal loyalty often lead to a desire to protect the existing channel members from any potential loss of volume. To succeed, firms need a well-thought-out implementation plan for channel migration. Such an implementation plan should address the following five questions:17

- Is there a shared understanding of the problem or opportunity?

- Is there a top management mandate for change?

- Is there adequate bottom-up involvement?

- Are there clear timetables and milestones?

- Have we addressed the human problem of change?

Sharing the results of a distribution strategy audit and constantly communicating the strategic logic behind the channel migration builds shared understanding. Managers will more likely generate shared understanding by asking those with a stake in the decision to participate in the audit. As far as possible, however, one should have market research behind the conclusions to focus the discussion on facts rather than unsubstantiated opinions and passions.

If a change in distribution channels threatens the volume in the existing channels, then the new channel champion will face stiff resistance from managers of the existing channels. It helps channel migration efforts if such resisters have heard top management’s mandate for change. The CEO should never declare existing distribution institutions sacrosanct. For example in 1996, Donald V. Fites, then chair and CEO of Caterpillar, publicly proclaimed, “We’d sooner cut off our right arm than sell directly to customers and bypass our dealers.”18 If consumer buying behavior, competitive environment, or the nature of the company’s products change significantly, such statements reduce future degrees of freedom and lock the managers into particular types of distribution institutions rather than selling in those channels where consumers wish to buy.

Once a company has decided to exit or enter certain channels, managers should ask for suggestions about implementation to create broad bottom-up involvement. Furthermore, a major change in channel structure will affect the job descriptions and careers of managers interfacing with existing channels. To help these people cope with change, top management should adjust compensation, make training available, and offer new job assignments.

Finally, since channel migration may take several years, managers should use a timetable with milestones that plot how the company’s sales should migrate across the various channels over time, to track progress and suggest course corrections.

Step 4: Actively Manage Channel Conflict

The addition of a new distribution channel, whether it is the Internet, an emerging low-cost indirect channel, or a new manufacturer sales force, brings with it the potential for additional sales volume, but at the cost of greater channel conflict. Channel conflict occurs because the existing channels perceive the new distribution channel to be chasing after the same customers with the same brand.

As happened at Compaq, the fear of channel conflict can paralyze a company. But some amount of channel conflict is healthy.19 The lack of channel conflict in a company’s distribution network is usually a sign of market coverage gaps. In fact, much of what channel members call conflict is healthy competition. Therefore, the objective of conflict management should not be to eliminate channel conflict but rather manage it so that it does not escalate to destructive levels.

From the manufacturer’s perspective, channel conflict becomes destructive when the existing distribution channels reduce support or shelf space for the manufacturer due to the emergence of the new channel. For example, when Estée Lauder set up a Web site to sell its Clinique and Bobbi Brown brands, the department store Dayton Hudson reduced shelf space for Estée Lauder products. In extreme cases, an existing distributor may even drop the brand, as happened when Gap decided to stop stocking Levi’s and concentrate on its own brands after Levi’s began expanding its distribution.

Channel conflict becomes particularly destructive when parties take actions that hurt themselves in order to hurt the other party. In 2002, Albert Heijn, the largest Dutch supermarket chain, boycotted some of Unilever’s brands to retaliate against the manufacturer. While this was resolved quickly, Albert Heijn could have lost brands such as Bertoli mayonnaise and Cif cleaning products, which have very high brand loyalty amongst Dutch consumers.

While none are a panacea, several channel conflict management strategies exist, which can help avoid destructive conflict during, and after, channel migration. These are part of the arsenal of any multichannel marketer.

Position Channels Against Segments. Since different channels have unique value curves, they reach distinct segments. Thus the rationale for having multiple channels should always be built on a clear end user segmentation strategy. For example, when Avon, which has traditionally used half a million direct sales representatives in the United States to sell its line of cosmetics, opened retail kiosks in malls, it found that 90 percent of the customers buying at these kiosks had never purchased from Avon before.20 The kiosks were reaching a new segment.

When the convenience store complains to the manufacturer about the prices at which Wal-Mart is selling its products, the manufacturer must explain that a convenience store cannot compete with Wal-Mart on prices for the price-seeking customer. Instead, the convenience store must compete on saving the consumer time on travel, shopping, and transaction processing, all at a reasonable price premium. They serve two different segments and each should specialize in its target segment. Of course, the brand owner should balance the number of distribution points within a particular distribution channel with the size of the segment that the channel reaches.

Dedicate Products and Brands to Channels. A popular method of managing channel conflict is to dedicate parts of the product line to different channels of distribution. Many designers have managed the conflict with their existing retailers by developing special products for their factory outlet stores in order to reduce the conflict with department stores. Similarly, many luxury brand companies, like Camus Cognac and Guylian chocolates, offer special pack sizes and products that attract travelers at dutyfree airports to minimize the conflict with their regular main street retailers. On the Internet, manufacturers can offer the SKUs that retailers are usually not willing to carry. At the extreme, some manufacturers dedicate different brands to different channels, sometimes referred to as channel brands. For example, MyTravel, a tour operator in Sweden, formerly distributed its Ving brand directly and developed the Always brand for travel agents. Likewise, Merrill Lynch allowed third parties to sell only Mercury funds while Merrill funds were restricted for in-house sales.

While having unique channel products or brands is sometimes seen as a resolution to the channel conflict problem, it is often unsustainable. Unless the product or the brand is targeted only to those customers buying in a particular channel or is unpopular, other distribution channels will quickly demand access to them. It took many years of pleas by travel agents before the highly successful Ving brand was offered to them. The expansion of Ving to travel agents brought an immediate increase in volume, and research indicated that 80 percent of those customers buying Ving through travel agent had never purchased Always or Ving previously. Similarly, in 2003, Merrill decided to close down the Mercury brand by consolidating those funds within Merrill Lynch.

Expand Channels and Sales Simultaneously. Having a new “hit” product helps facilitate channel migration. Goodyear managed the migration to the mass merchandisers with only a reasonable amount of conflict by restricting the distribution of its new Aquatred tire to the independent dealers. This allowed the independent dealer to protect their profitability and sales volume through the higher margin, higher value Aquatred tire. Expanding channels when revenues are growing is easier as existing dealers are less likely to see absolute declines in sales and profits.

Adopt Dual Compensation and Role Differentiation. To lessen channel conflict, some manufacturers agree to compensate the existing channels for sales through the new channel. While it may be perceived as just buying off the support of the existing channels for the channel migration, it can be useful if the existing distribution is given a role to perform in supporting the new channel. For example, when Allstate started selling insurance directly off the Web, it agreed to pay agents a 2 percent commission if they provided face-to-face service to customers who got their quotes off the Web. However, since this was lower than the 10 percent commission that agents typically received for offline transactions, many agents did not like it. Yet, it did help lower the negative backlash.

Many manufacturers will be unable to avoid selling on the Internet directly as consumers are seeking that distribution solution. Yet, they lack the logistical ability to fully satisfy the consumers. Using the existing channel partner can be a useful complement. Maytag, for example, joined forces with its retail partners to offer online sales. After the consumer decides on an appliance, she is shown the availability and pricing information from a local dealer who provides the fulfillment and installation. Similarly, Levi Strauss discovered that handling online returns was too costly, and that consumers preferred returning products to a physical store anyway. Consequently, it discontinued sales from its Levi’s and Dockers Web sites and let J.C. Penney and Macy’s sell Levi’s on their sites.

Avoid Overdistribution. The temptation for manufacturers is to expand the number of distribution points to increase sales. However, generally, the greater the number of points distributing a brand, the less support each distribution point will give to the brand. Thus, manufacturers, especially of prestigious goods requiring a high level of service, must be careful not to overdistribute their products. Having too many channels chase too few consumers can have a deleterious impact on sales.

Bang & Olufsen (B&O), a major Danish high-end player in the electronics industry, easily distinguished by its distinctive Bauhaus-inspired designs, was on the verge of bankruptcy in the early 1990s. It had too many retailers selling B&O products next to rival brands, and as a result, the focus was frequently on price. Unable to make adequate margins, retailers lowered their service in support of B&O products, which further weakened the brand’s position as a luxury lifestyle product. Between 1994 and 1997, B&O cut a third of its dealers in Europe and dropped from 200 to 30 dealers in the United States. It then invested in improving the remaining dealers by setting up partially owned and franchise boutiques dedicated solely to B&O. Greater control and more dedicated retailers helped reposition B&O as a top-of-the-line audiovisual brand and sales rebounded despite having fewer dealers.

Treat Channels Equitably. Notwithstanding all of the above, in the face of multiple channels typically selling at different price levels, there will be channel conflict. Some retailers will be upset that the prices they pay the manufacturer are higher than those charged to other retailers or to the direct sales force. They will often feel that the manufacturer is favoring other channels at their expense. While they may never fully overcome these concerns, the best antidote is to treat channels equitably and in a transparent manner. If the manufacturer’s prices differ across channels, it should be based on how the particular channel member performs. Tesco and Wal-Mart do receive lower prices, but it is because they engage in practices (buying large quantities, allowing electronic transactions, not demanding in-store help and promotions) that lower the manufacturer’s cost to serve them.

Conclusion

The emergence of a new distribution channel raises several questions regarding the company, its competitors, the existing channels, and customers (see “Checklist for Channel Migration”). Any robust channel migration process must address them.

Innovation in distribution channels typically promises some combination of opportunities for serving overlooked customer segments, offering new value propositions, or the use of a more cost-efficient business model. For example, office superstores like Office Depot found a niche because of the poor service that other office product dealers were giving to small business customers. Priceline offered a new value proposition of cheaper airline fares for those who were willing to relinquish brand and departure time preferences.

Focused on defending existing distribution assets and value networks, established companies tend not to counterattack when a new innovative distribution channel challenges them.21 When industry distribution structures change, traditional industry leaders repeatedly neglect the fastest-growing market segments. New distribution opportunities rarely fit the way the industry approaches the market, defines it, or organizes its value network to serve it. Therefore, innovators in distribution have a good chance of being left alone for a long time. The problem confronting managers of established firms is that they must cannibalize their own profitable businesses for questionable returns from emerging channels. But if they don’t do it, their competitors will, and it is always better to have all the cannibals in the family.

Checklist for Channel Migration

Customers

- What service outputs will the new channel provide?

- Which segments will the new channel target?

- Which markets will the new channel operate in?

- How much additional industry volume will the new channel generate?

Channels

- How will the relative importance and power of existing channels change?

- How will existing channels react strategically to the new channel?

- What level of conflict will the new channel generate?

Competitors

- Which competitors will enter the new channel?

- What changes in channel incentives to existing members will competitors try?

- How will relative market share positions change?

- What are the competitive implications of being the leader, fast follower, or laggard in the new channel?

Company

- Which products and services will flow through the new channel?

- What will be the cost to serve through the new channel?

- What new competences do we need to enter the new channel?

- How will we manage channel conflict?

In evaluating the urgency for channel migration, one must consider the speed at which channels are changing. The internal rate of change in distribution strategy must match the external rate of change in consumer channel preferences. Channel migration within established firms only happens when the CEO is willing to sign off on it. The engine must be consumer shopping patterns and preferences but the CEO must grease the wheels. As one CEO in the process of changing channels remarked to me, “We have finally decided to stop selling where we want to and instead have begun to sell where customers want to buy.” History suggests that most companies cling too long to declining distribution networks.