FIVE

From Branded Bulldozers to Global Distribution Partners

No company is an island.

HISTORICALLY, POWER IN distribution channels has rested upstream with brand marketers such as Philip Morris and Sara Lee, manufacturers such as Ford Motor Company and Caterpillar, or franchisers such as McDonald’s and PepsiCo. In contrast to these multinational suppliers, most retailers, dealers, and franchisees were local and fragmented. There was within each country a large owner-operated sector in distribution, which in retailing is romantically referred to as “mom and pop.” Retailing, and more generally distribution, therefore acquired an image of being a simple, unsophisticated business, undeserving of attention from superior trained minds, be they academics or M.B.A.’s from prestigious schools.

In such an environment, supplier organizations were optimized for trade relations with small, vulnerable, and local distribution partners. In terms of structure, manufacturer and franchiser organizations typically coalesced around products and countries. And in terms of policies and practices, these suppliers were predisposed toward utilizing their superior coercive power over resellers in order to achieve distribution objectives.

Over the past two decades, there has been a remarkable shift in power downstream from suppliers to distributors and retailers. The increasing power of resellers has been driven by the rise of horizontal buying alliances, megaformats such as category killers and superstores, as well as mergers and acquisitions. Some of the most significant M&A activity has been cross-border mergers. The worldwide revenues of the largest retailers such as Ahold, Carrefour, and Wal-Mart now exceed, or at least compare favorably with, those of the leading branded manufacturers.

With distribution consolidation, fewer customers now account for a large proportion of the manufacturers’ sales. A study of thirty-seven consumer packaged goods manufacturers in 2000 indicated that, on average, the top five international customers accounted for 32 percent of sales, up from 21 percent five years ago and expected to increase to 45 percent over the next five years.1 When the five largest global retailers account for almost half of a supplier’s business, they have tremendous negotiating clout over their suppliers.

Since manufacturer prices for the same product can vary by as much as 60 percent among countries, global retailers are increasingly demanding uniform worldwide prices, much to suppliers’ dismay. John Mentzer, president and CEO of Wal-Mart’s international division, declared, “We are using global sourcing to get the best products worldwide, to have the best stock worldwide, to leverage our supply chain and to get what we call transparent pricing worldwide. Transparent pricing to us is the same pricing adjusted for freight, duty, and local differences.”2

The retailer’s adoption of a global pricing policy can dramatically affect the manufacturer. For example, Carrefour, the secondlargest retailer in the world, which operates in thirty-three countries, insisted that a leading packaged goods company use the lowest price in any country as the global price for each international SKU. The consumer packaged goods firm estimated that if Carrefour was allowed to pick the lowest price for every international SKU, it would lower their annual revenues from Carrefour by 7 million euros on a turnover of 100 million—and most consumer packaged goods firms hardly make a 7 percent after-tax return on sales.

Serving end users through powerful international distributors or retailers requires manufacturers to reorient their organizations around customers and relationships, not countries and products. As this chapter reveals, using global retailers effectively demands transformation in strategy, organization structure, information systems, human resource management, and, above all, a fresh mind-set.

Predictably, managers who attempt such changes themselves face stiff external and internal resistance. CEOs of major manufacturing and franchising companies often cannot fathom their channel partners’ perceived lack of trust in them. Furthermore, the necessary organizational changes tend to disrupt the delicate power equilibrium between individuals and divisions within the firm. The current CEO of a packaged goods company articulates this transformation challenge well: “The fact that we are a multidivisional, multifunctional, multinational, multiproduct and multiplant company is not the customer’s problem.”

To transform the organization, the company needs ample resources and a committed change leader, often the CEO or someone whom the CEO openly supports. Today, CEOs themselves often wrestle with global retail issues because of the aforementioned price pressures threatening the overall bottom line.

The Challenge from Global Retailers

The growth of global retailing has been substantial. For example, Ahold, Carrefour, and METRO each operate in more than twenty-five countries; Aldi, Auchan, Rewe, Tesco, and Wal-Mart operate in ten or more. While most of these examples feature the packaged goods industry where changes have been the most traumatic for suppliers, we can see these trends—distribution consolidation, increased globalization, increasing point-of-sale power, and value migration downstream—in industries as diverse as apparel, chemicals, entertainment, financial services, paints, and personal computers. Consider the following cross-border examples:

- Global retailers who operate under their own name include Amazon, Toys “R” Us (with over 1,600 stores in 27 countries), Hennes & Mauritz in fashion retailing (with 840 stores in 17 countries), and IKEA in furniture (with over 150 stores in over 30 countries).3 Outside the United States, Blockbuster video has more than 2,600 stores in 27 countries and Starbucks Coffee has 900 stores in 22 countries.4

- The British retailer Kingfisher, an emerging global retailer that has grown through acquisitions, operates a portfolio of brand names. In the home improvement sector, Kingfisher has about 600 stores in 15 countries including B&Q in the United Kingdom, Castorama and Brico Dépôt in France, Réno-Dépôt in Canada, NOMI in Poland and Koctas in Turkey. It also owns about 650 electrical retail stores in 7 countries including Darty and But in France, Comet in the United Kingdom, New Vanden Borre in Belgium, BCC in the Netherlands, ProMarkt in Germany, and Datart in the Czech and Slovak Republics.5

- Tech Data Corporation’s 1998 acquisition of Germanbased Computer 2000 AG created a Fortune 100 company. It generated annual sales of $15.7 billion in the fiscal year ending January 31, 2003, distributing microcomputer related hardware and software products from vendors such as IBM and Cisco to more than 100,000 technology resellers worldwide.6

The Retailer Challenge to Manufacturers

The emergence of global players has transformed retailing into a sophisticated, technologically intensive, and systems-driven business enviable by NASA’s standards. Not satisfied as mere merchants, retailers have developed quality store brands.7

Powerful global retailers are demanding more from their branded multinational suppliers—gains from scale, synergies, and speed. This translates into demand for differentiation through unique offers and distinctive marketing concepts; efficiency gains through standardized back office functions; and gains in knowledge from branded suppliers like Nestlé or Unilever that have relatively greater multinational expertise in new business development in emerging markets.

In every part of the world, global customers expect coverage, speed, consistent and high-quality service, as well as extraordinary attention. This expectation requires manufacturers to provide a single point of contact, uniform terms of trade, as well as worldwide standardization of products and services.

The retailers’ global procurement strategies push manufacturers into offering price concessions and enhanced fees such as trade promotions, slotting allowances, and failure fees. For example, one small Chinese supplier of bedding to Carrefour complained, “We must pay 4 percent of our annual sales each year just to keep our contract. On top of that are so-called holiday fees of around Rmb 2,000 each five times a year [and] a flat Rmb 10,000 fee called ‘running the store fee.’”8

Global customers hate to learn that they were not offered the lowest prices. They demand more uniform, more transparent global prices. However, under the pretext of local cost or competitive considerations, multinational manufacturer prices for the same or similar products differ dramatically across countries, leading to amusing, if not awkward, situations. For example, in 2000, Tesco, then about a $30 billion dollar retailer, acquired a small thirteen-store supermarket chain in Poland called Hit, which was obtaining better prices from its suppliers than Tesco was. Pity the poor supplier representatives who had to explain the logic of their worldwide pricing structure to Tesco management.

The Challenge of Global Integration for Retailers

Historically, retailers, especially food retailers, have subscribed to the view that all retailing is local. Daniel Bernard, Chairman and CEO of Carrefour, observed, “Retail is the image of the country in which it lives. You must adapt your food and other products to the local culture.”9 Because of this decentralized view, global food retailers are still learning to leverage their global operations. While they may make more decisions centrally on private labels and category management, for example, their actual level of global integration is quite low. Most global food retailers have not yet centralized worldwide purchasing functions. Currently, they fancy overriders—basically a percentage kickback from the supplier to the retailer’s headquarters on the supplier’s worldwide sales to the retailer.

Carrefour, like many other global retailers, is attempting to integrate its global operations. Yet, as of today, it cannot provide detailed benchmarking data across all thirty-three countries. At last count, the data was available for only twenty-three countries. In terms of purchasing, Carrefour has integrated its nonfood merchandise but still handles food sourcing locally.

Regrettably for manufacturers, retailers recognize that global integration is their key challenge. The chief executive of Ahold observed, “In the next three years, the various supermarket chains must find more synergies. Their sourcing will be completely centralized, with one center for procurement of perishable goods, which connects with the foodservice operation.” The ubiquity of this view among global retailers means that life will only get tougher for brand manufacturers.

Developing a Relationship Mind-Set

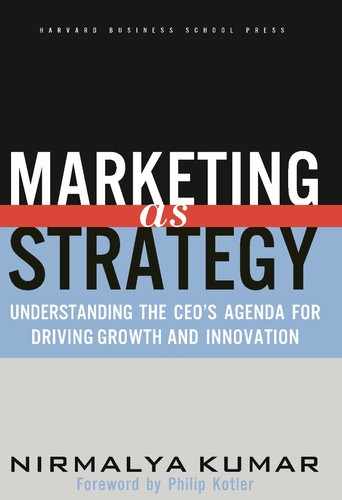

To implement global account management, suppliers and their global retail partners must develop a shared relationship-building mind-set. Unfortunately, human nature leads us to exploit our relative power over other players. As figure 5-1 indicates, when suppliers are strong and resellers are weak, the former tend to bulldoze the latter. Historically, manufacturers have done just that, pushing their brands and promotion plans onto retailers for implementation. But as retailers have become powerful and adversarial, they have turned vulnerable manufacturers into shelf-space bidders.

Manufacturer-Reseller Relationship Matrix

Source: Adapted from Peter M. Freedman, Michael Reyner, and Thomas Tochtermann, “European Category Management: Look Before You Leap,” McKinsey Quarterly 1 (1997): 156–164.

Clearly, the relationship between retailers and manufacturers must change to reflect this new reality. Using the framework of figure 5-1, powerful manufacturers have moved from being “branded bulldozers” to a “tug-of-war” relationship with retailers. The challenge is to ultimately change this relationship into a “strategic partnership.” The relationship between Procter & Gamble (P&G) and Wal-Mart is an excellent example of how a relationship evolves through these three phases.10

Two Tough Companies Learn to Dance Together

Word has it that P&G and Wal-Mart are two tough negotiators. Historically, P&G has wielded its enormous sword to dominate the trade, using its comprehensive consumer research to secure increased shelf space for its brands. Before retailers developed sophisticated point-of-sale systems to generate their own data, they could not dispute P&G’s findings. Over the years, P&G established its reputation as a “self-aggrandizing bully of the trade.”11

For its part, Wal-Mart asked its suppliers for rock-bottom prices, extra service, and preferred credit terms. In 1992, it instituted a policy of dealing directly with manufacturers, and only those that invested in customized electronic-data-interchange technology and put bar codes on their products. Manufacturers that depended on the volume and growth that Wal-Mart delivered played by the policy.

As one might expect, P&G initially dictated to Wal-Mart how much P&G would sell, at what prices, and under what terms. In turn, Wal-Mart threatened to drop P&G merchandise or give it poorer shelf locations. There was no sharing of information, no joint planning, and no systems coordination. Prior to 1987, no corporate officer of P&G had even contacted Wal-Mart. According to Sam Walton, the founder of Wal-Mart, “We just let our buyers slug it out with their salesmen.”12

In the mid-1980s, this adversarial relationship began to change. On a now-legendary canoe trip, Sam Walton and Lou Pritchett, P&G’s vice president of sales, agreed to reexamine the relationship between the two companies. They gathered the top ten officers of each company for two days to develop a collective vision of the future. Within three months, they established a team of twelve people from different functions in each company to convert that vision into an action plan. It examined how the companies could use information technology to increase sales and lower costs for both parties.

The result was a sophisticated efficient consumer response (ECR) partnership. This partnership enables P&G to manage Wal-Mart’s inventory of any given product, such as P&G’s Pampers diapers. Procter & Gamble receives continuous data via satellite on sales, inventory, and prices for different sizes of Pampers at individual Wal-Mart stores. This information allows P&G to anticipate Pampers sales at Wal-Mart, determine the number of shelf racks and quantity required, and automatically ship orders. Electronic invoicing and electronic transfer of funds complete the transaction cycle. The short order-to-delivery cycle enables Wal-Mart to pays P&G for the Pampers soon after the consumer buys the merchandise.

This partnership has created great value for consumers in the form of lower prices and more availability of their favorite P&G items. Through cooperation, the two giants have eliminated superfluous activities related to order processing, billing, and payment; reduced the number of sales calls; and dramatically reduced paperwork and opportunities for error. The orderless order system also lets P&G produce to demand rather than to inventory. Furthermore, Wal-Mart simultaneously reduced its inventory of Pampers and the probability of stock-outs, thereby avoiding lost sales for both parties. By collaborating, the two have turned a win-lose into a win-win proposition of reduced costs and greater revenues for both parties. Today, Wal-Mart is P&G’s largest customer, generating about $7 billion in sales, or greater than 17 percent of P&G’s worldwide revenues.

Over the last fifteen years, these two giants have developed a partnership based on mutual dependence: Wal-Mart needs P&G’s brands and P&G needs Wal-Mart’s access to customers. Naturally, the relationship has undergone the trust-building growing pains that are a benchmark for manufacturer-retailer symbiosis: Wal-Mart trusts P&G enough to share sales and price data and to cede control of the order process and inventory management. Procter & Gamble trusts Wal-Mart enough to dedicate a large cross-functional team to the Wal-Mart account, adopt everyday low prices (thereby eliminating special promotions), and invest in a customized information link. Instead of focusing on increasing sales to Wal-Mart, the P&G team concentrates on increasing sales of P&G products through Wal-Mart, maximizing both companies’ profits.

Create Trust, Not Fear, in Distribution Relationships

The P&G and Wal-Mart partnership illustrates that exploiting power in distribution channels pays in the short run but not in the long, for three reasons.13 First, extracting unfair concessions will burden a firm as power positions change over time. For instance, when Migros, a supermarket chain in Switzerland, was founded, the large branded manufacturers refused to supply it rather than upset their traditional mom-and-pop retailers. Without branded products, Migros adopted an exclusively private label format. Today, Migros is the largest retailer in Switzerland with private labels accounting for 90 percent of its total sales volume. Most major brands, such as Coca-Cola and Nescafé, can’t be found on its shelves.

Second, when companies systematically exploit their advantage, the victims ultimately resist by developing countervailing power. For example, by banding together, automobile dealers and franchisees successfully lobbied lawmakers in Europe and the United States to pass particularistic legislation that restricts franchisers like Ford or McDonald’s from sanctioning or sacking them. Apparel designers such as Giorgio Armani, Hugo Boss, Liz Claiborne, and Donna Karan opened their own outlets to escape bulldozing department stores that unilaterally returned products, took discounts off manufacturer invoices, and delayed payments.

Third, only by developing mutual trust and collaborating closely can manufacturers and their resellers deliver the greatest value to end users. While managers frequently use the word trust in distribution channels, they often fail to define it precisely. Trust involves dependability and faith.14

A dependable distribution partner is honest and credible. For example, one manufacturer signed onto a retailer’s global promotion that cost more than a country-by-country promotion would have.15 However, the retailer then failed to execute the promotion effectively in all its stores around the world.

Dependability alone does not suffice. Someone who promises to punish his partner and then does so is honest and credible, but not trusted. In trusting relationships, the parties believe that each cares about the other’s welfare and will take into consideration the effects of its actions on the other party—that both will act in good faith.

Dealers and retailers who trust the manufacturer are less likely to seek alternative sources of supply, more likely to produce sales, and more forgiving of the manufacturer.16 For example, in the consumer durable industry, dealers who trusted their manufacturers generated 78 percent more sales for the manufacturer.17

Given the benefits of trust, even those suppliers who can potentially behave like branded bulldozers should attempt to build trusting relationships with resellers. However, managing distribution relationships based on trust instead of power requires a leap in mind-set and culture (see table 5-1).

The Power Versus Trust Game

| The Power Game | The Trust Game | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modus Operandi | Create fear | Create trust | ||

| Guiding Principles | • | Pursue self-interest | • | Pursue what’s fair |

| • | Win-lose | • | Win-win | |

| Negotiating Strategy | • | Avoid dependence by playing multiple partners off against each other | • | Create interdependence by limiting the number of partnerships |

| • | Retain flexibility for self but lock in partners by raising switching costs | • | Both parties signal commitment through specialized investments, which lock them in | |

| Communication | Primarily unilateral | Bilateral | ||

| Influence | Through coercion | Through expertise | ||

| Contracts | • | “Closed,” or formal, detailed, and short-term | • | “Open,” or informal and long-term |

| • | Use competitive bidding frequently | • | Check market prices occasionally | |

| Conflict Management | • | Reduce conflict potential through detailed contracts | • | Reduce conflict potential by selecting partners with similar values and by increasing mutual understanding |

| • | Resolve conflicts through the legal system | • | Resolve conflicts through procedures such as mediation or arbitration | |

Source: Adapted from Nirmalya Kumar, “The Power of Trust in Manufacturer-Retailer Relationships,” Harvard Business Review (November–December 1996): 92–105.

Adopt Fairness Principles in Relationships

To develop trust, the more powerful party must treat the weaker one fairly. Fairness encompasses two distinct types of justice: distributive justice, or fairness of outcomes received, and procedural justice, or fairness of policies and practices.18

Distributive Justice. Distributive justice refers to a party’s perception of the fairness of earnings and outcomes that it receives from the partnership. It refers to “pie sharing” or the division of benefits and burdens between partners. Compensating channel partners appropriately by allowing them a fair return can have long-term benefits that are not immediately apparent. For example, a few years ago, Buick cars consistently received higher customer satisfaction ratings than Oldsmobile, even though they were built at the same General Motors plant. Why? Buick was paying its dealers fifteen dollars per hour more for warranty work than Oldsmobile. When customers visited Oldsmobile dealers with a small problem, the dealers responded, “All cars do that;” Buick dealers fixed it. How dealers treat the customer factors into customer satisfaction.

Procedural Justice. Procedural justice refers to “due process” or the fairness of a party’s procedures and policies regarding its vulnerable partners. Procedurally fair systems in distribution rest on six principles:

- Bilateral communication is the willingness of the firm to engage in two-way communication with its channel partners. The more powerful companies in the distribution channel tend to listen less to the other members in the system. Companies that develop trust establish practices that solicit input from channel partners. For example, at Anheuser-Busch Companies, the chairman meets with the fifteen-member wholesaler panel at least four times a year, to hear suggestions and complaints.

- Impartiality is the consistency of the company’s channel policies across all channel partners. While every channel partner can’t be treated identically, partners can be given equitable opportunities.

- Refutability is the ability of the smaller or more vulnerable partners to appeal against the more powerful party’s channel policies and decisions. Manufacturers such as Caterpillar, DuPont, and 3M have dealer advisory councils at which dealers can air their concerns.

- Explanation is providing one’s partners with a coherent rationale for channel decisions and policies. It calls for greater transparency.

- Familiarity is an understanding of the local conditions under which channel partners operate. Before Marks & Spencer enters into a relationship with a new manufacturer, it visits the manufacturer’s plants several times and hosts meetings among its buyers, merchandisers, and designers.

- Courtesy is treating a partner with respect. After all, relationships between companies are actually relationships between teams of people. Managers who recognize this fact are changing how they assign personnel to various accounts. Sherwin-Williams, the paint manufacturer, lets managers from Sears, Roebuck and Company help select the Sherwin-Williams people who will handle the Sears account.

Distributive justice and potentially large returns usually attract companies to a relationship, but procedural fairness holds the relationship together. Retaining partners by giving them higher margins than what they get from competitors is expensive because competitors quickly match them. Developing procedurally fair systems requires greater effort, energy, investment, patience, and perhaps even a change in organizational culture, but will more likely lead to sustainable competitive advantage.

Implement Efficient Consumer Response (ECR) Initiatives

ECR is a strategic initiative in which the retailer and manufacturer work closely together to eliminate excess costs and serve the consumer cheaper, faster, and better. In 1992, supermarkets and their suppliers embraced ECR as a powerful tool to optimize the supply chain and compete better against discounters such as Wal-Mart in the United States and Aldi in Germany.19 ECR included quick response models, continuous replenishment, cross-docking, electronic data interchange (EDI), and vendor managed inventory systems.

Kurt Salmon, a retail-consulting firm, was commissioned to document the potential savings. It found that ECR could reduce costs in the supermarket distribution chain by 11 percent, which translated into $30 billion in the United States and $50 billion in Europe. As a cross-functional program, the sources of savings came from better capacity utilization in production, reduced promotion expenses and fewer new product failures in marketing, lower administration costs in purchasing, increased utilization of warehouses and trucks for the logistics systems, less clerical and accounting staff in administration, and higher sales per square foot at the store level. It was anticipated that 54 percent of the benefits would flow to manufacturers while 46 percent of the savings would go to retailers. Not surprisingly, manufacturers and retailers shared great enthusiasm for ECR.

Despite its widespread adoption, ECR has disillusioned CEOs of suppliers. The CEO of one of the largest packaged goods companies remarked, “If there was a dollar to be made from ECR, I haven’t seen it.”20 My study of the suppliers of Sainsbury’s, one of the United Kingdom’s two largest retailers, revealed that with greater levels of ECR implementation in their relationships with Sainsbury’s, suppliers achieved higher levels of profitability, turnover, and growth.21 However, they also reported feeling less equitably treated. These findings explain the prevailing perception of supplier CEOs: that they do not benefit from ECR. Objectively, suppliers do obtain a payback from ECR, but these benefits are perceived to be relatively small compared to what the retailer is perceived to be receiving. Consequently, suppliers feel that that they do not profit from ECR. Yet despite the current disenchantment, suppliers should adopt ECR while accepting the reality that their shares of the returns will be small compared to global retailers.

Customer-Centric Global Account Management

Whereas some companies are moving fast on global account management, most manufacturers have been reactive rather than proactive. What prevents them from reorganizing for global customers is a myriad of internal constraints. Historically, the power in decentralized companies such as Unilever and Nestlé has resided with country managers. In more centralized companies like P&G, most of the power rests with business unit managers (usually organized around product divisions).

Customer-centric global account management requires a single strategic interface for each global customer, which is supported and reported to by business units and country organizations. Delivering an integrated solution requires a greater understanding of the individual retailer worldwide and greater coordination among the supplier’s sales and supply chain operations around the world.

Marketing plans and supply chains must become customer-centric instead of country-centric. Implementation involves shifting responsibilities and thereby changing power balances. It necessitates resolving conflicts between what is best for the global customer and what is best for the supplier’s local country organization. 22 The ensuing power struggles over who owns the account, how to assess performance, and appropriate incentive systems may seem wasteful but they are real. Companies must move fast, cede control to the center, and resolve their internal problems. To deliver on global retailers’ demands for efficiency and lower prices, manufacturers must restructure to decrease potential losses through complexity of organization, work processes, and information.

The transformation challenges discussed within the context of the grocery retailing industry are also being confronted by other industries serving global accounts. Global account management is prevalent in many industries including advertising, airline, audit services, automotive components, hotel, insurance, petroleum, software services, and telecommunications. Examples include:

- IBM firing over forty different advertising agencies worldwide and consolidating the group’s entire $400 to $500 million account with Ogilvy & Mather.23

- Gates, a leader in belts, supplying General Motors plants worldwide with automotive equipment.

- Deloitte, Touche, and Tohmatsu auditing the accounts of several multinational companies.

Serving global customers is especially problematic when local offices of global account suppliers are independent (for example, audit, advertising, or consulting firms). The transformation required in multinational companies—into an organizational form and process whereby one person or team coordinates the worldwide activities serving a multinational customer—is a Herculean task.

In most companies, half-hearted steps to establish global account management alongside country and product organizations are not delivering the required integration. The situation will only worsen, especially if retailers set up global supplier teams to mirror the supplier’s global customer teams. For manufacturers to respond to the challenge of global retailers, changes are required at several levels including strategy, organization structure, information systems, and human resource management.

Strategic Transformation

Nothing is as useful as a well-developed, well-articulated strategy for global accounts. It guides key account managers and customer development team leaders when they are face-to-face with global retailers and under tremendous pressure to cede to everything the retailer demands. A clear strategy gives them the confidence to say to important global accounts, “No, we don’t do that,” with the knowledge that they have top management support and are following the corporate mandate.

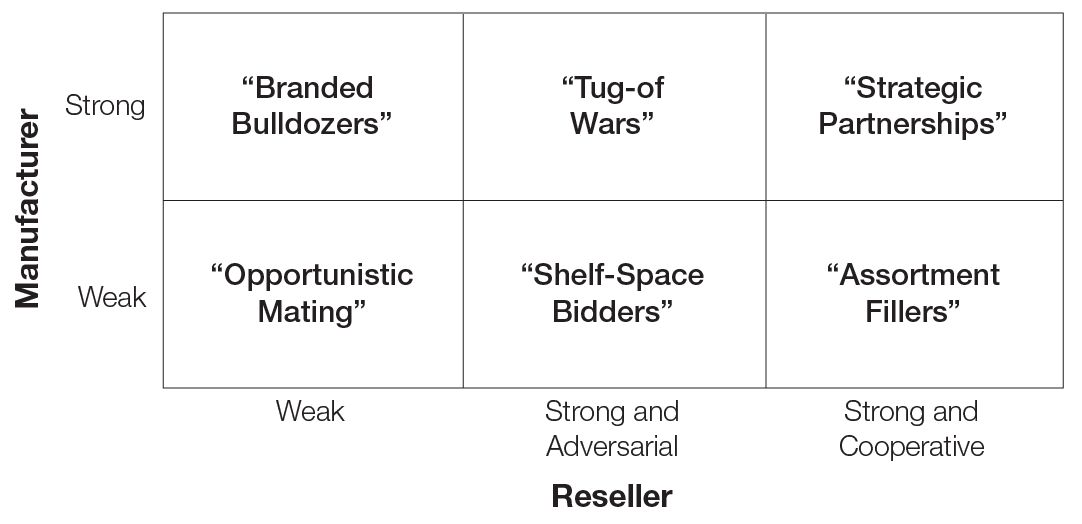

Developing the strategic vision and thrust for the global accounts—perhaps ten customers, accounting for 25 to 50 percent of the firm’s total business—must be the responsibility of the CEO and top management. The stakes are too high for the CEO not to be actively involved in this process. Figure 5-2 shows one manufacturer’s attempt to understand its top twelve global retail accounts on the two dimensions of attractiveness of retailer for the manufacturer (for example, growth, attitude toward the manufacturer), and how coordinated the retailer is with respect to its international operations. Two managers on customer business development teams at one manufacturer noted the benefits of a well-articulated strategy:

Those that get that [strategy] right upfront and do the hard work to get it right tend to be almost always more successful than those that don’t.

I believe the single most important thing to do in team effectiveness is to get very clear directions. I don’t think you can get clear on roles, clear on your structure or get clear on your relationships if you are not clear on the direction.24

Manufacturer’s Global Retailer Portfolio

Common Policy. What is needed is a common policy on how to deal with global accounts.25 Is the company going to be proactive or reactive to their demands? Perhaps the appropriate stance toward global retail accounts depends on the position of the manufacturer.26 Manufacturers with strong brands and geographies should aspire to category captain positions through partnerships with global retailers. Those manufacturers with strong brands but weak geographical coverage may wish to use global retailers to expand into markets where they are currently underrepresented. Perhaps companies with weak brands but strong geographical coverage will turn into private label suppliers to global retailers, while those with weak positions may have no choice but to exit the category or customer segment.

Brand Portfolio Rationalization. Some strategic imperatives result from global consolidation and fewer accounts. Global retailers push global brands and use private labels to displace weaker local brands. Consequently, as discussed in chapter 6, manufacturers must take a long, hard look at brand rationalization. The logic for continued support of weak or local brands is becoming harder to defend. It only pushes the relationship between the supplier and the retailer into the “shelf-space bidder” and “assortment filler” boxes of figure 5-1. Consequently, P&G has eliminated many “also-ran” brands including Aleve painkiller, Lestoil household cleaner, and Lava soap.

SKU Rationalization. Global retailers deploy sophisticated category management systems that spew detailed results on which SKUs are performing. Suppliers cannot push weaker SKUs onto retailers and should delete those SKUs that are sub-par. Almost every major branded manufacturer has embarked on an SKU rationalization program over the past five years. For example, P&G has reduced its number of SKUs by 25 percent. Even the product line of a leading brand such as Head & Shoulders shampoo has gone from thirty-one to fifteen SKUs.

Transparent Pricing Strategy. Most retailers now recognize that the demand for uniform global pricing is mostly a negotiating strategy since there are few uniform global products (except Gillette razors or Marlboro cigarettes, for example). Furthermore, comparing net prices across countries is difficult. Typically, the list price in each country is subject to

- quantity discounts (based on volume purchased),

- logistics discounts (based on whether the retailer orders truckloads, pallets, or cases),

- various behavioral discounts (for example, retailer’s use of EDI, cash payment, or continuous replenishment),

- marketing allowances (for approved promotions and joint, or “cooperative,” marketing activities), and

- performance-based incentives (for example, retailers achieving certain share for manufacturer in the category).

Global retailers have legitimate concerns about the transparency of manufacturer global prices and the standardization of terms and conditions. While prices may differ across countries, manufacturers could harmonize their pricing structures. Discounters like Aldi and Wal-Mart have performed well because they prefer a simpler low net price—no discounts. This preference allows manufacturers to simplify their systems, use a single IT platform, and standardize invoicing, thereby cutting considerable costs that add little value for the end user.

Procter & Gamble has adopted more straightforward, logical, and relatively transparent pricing policies. It withholds actual prices across customers but shares the logic of its pricing structure so that it will not find itself in a situation where it cannot justify its prices across different retail customers or countries.

Globally Competitive Supply Chains. Finally, as global retailers push for global pricing, manufacturers will need to restructure their operations into globally competitive cross-border supply chains. Many “national” factories and warehouses, especially in Europe, will lose their rationale for existence .27 Again, these tough decisions affect multiple stakeholders and require top management to champion the process.

Organizational Transformation

Companies tend to choose one of three organizational orientations to global accounts.28 First, some companies give primacy to the country organization. For example, Coca-Cola started and subsequently disbanded its European account management because the independent bottlers in individual countries operate autonomously. Second, and probably most pervasive, is a balanced approach where the local account manager reports to both the local country manager and the global account manager. A third, more recent structure, in cases where the company organizes around powerful global customers, assigns power to global account managers, not to local sales.

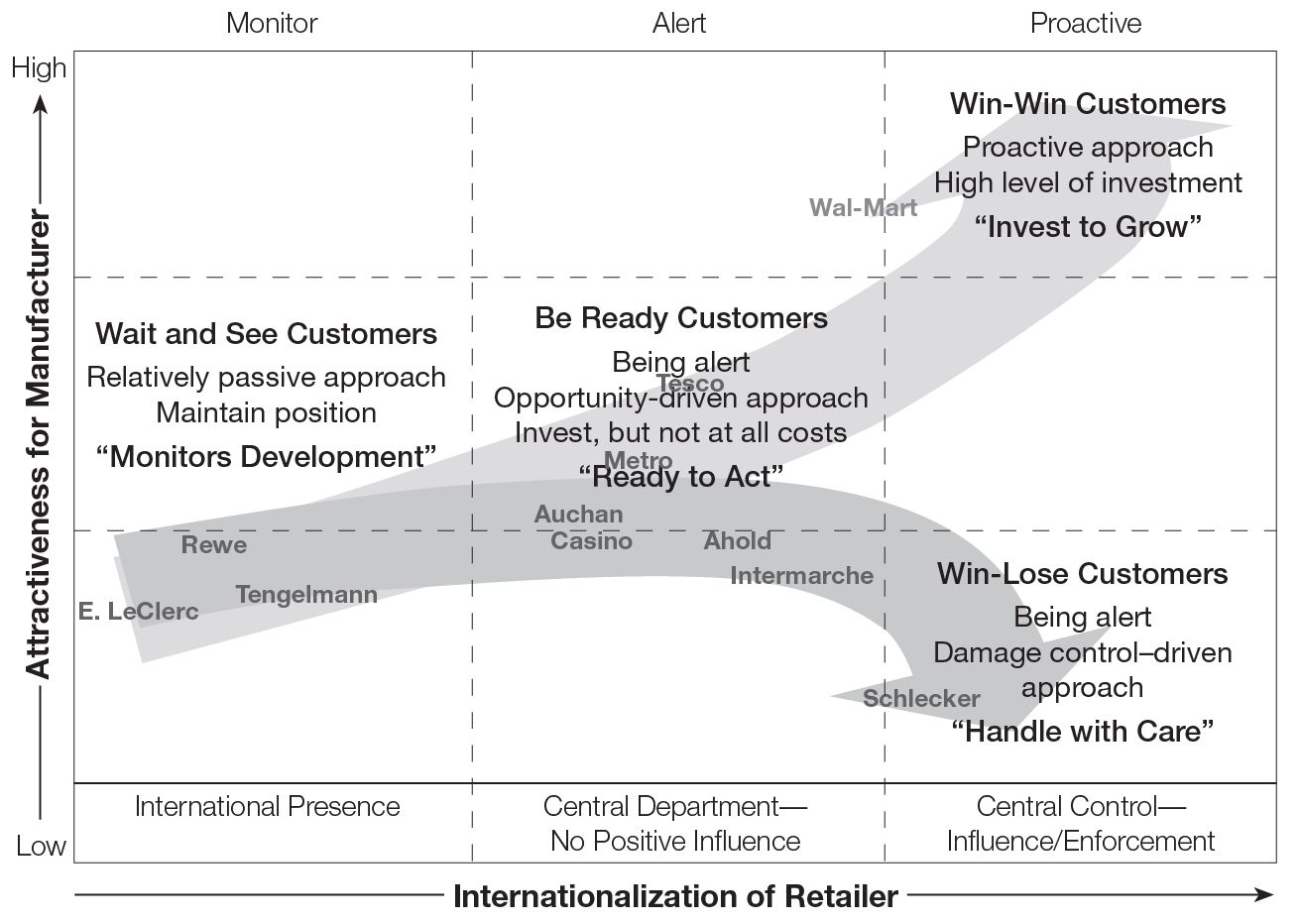

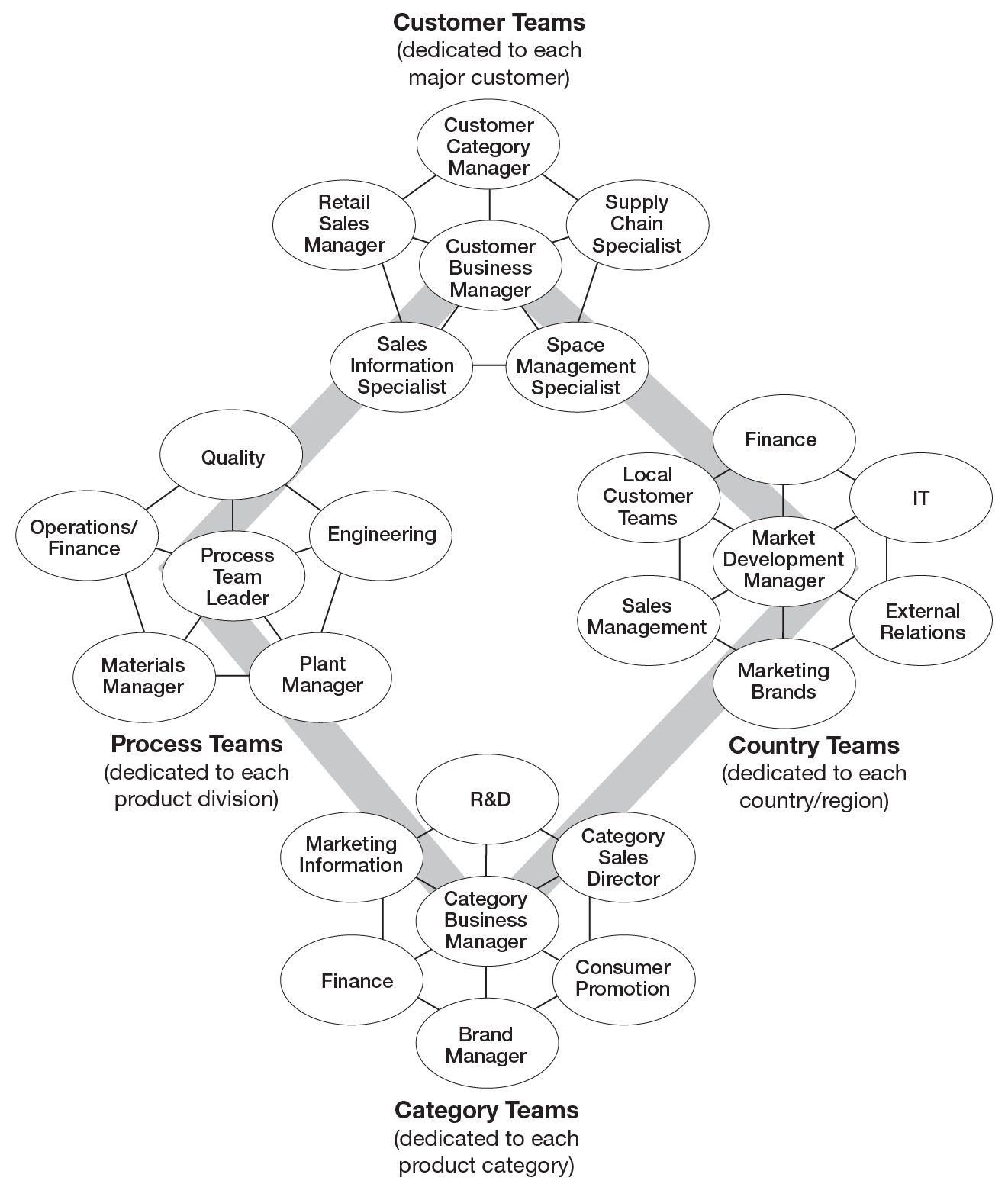

To present a single face to the global customer despite multiple points of contact, regardless of orientation, most firms are establishing global customer development teams, a P&G innovation illustrated in figure 5-3. These global customer teams run parallel to global business units and country organizations, yielding an intricate matrix organization.29

The Structure of P&G’s Global Customer Development Teams

Global Business Units. Procter & Gamble split its global business unit (GBU) organization along the major lines of business such as food and beverages, fabric and home care, health and beauty, and family care. Each GBU must articulate its strategy and ensure adequate development of the brands and products in its portfolio by driving product innovation and supporting global brands. Managers develop business unit plans and have worldwide responsibility for achieving the sales and profit objectives at this megacategory level.

Country Organizations. The traditional regional and country organizations are accountable for the country-level revenues and profits. They must understand the local consumers in their area, manage the local stakeholders, and serve local retailers. However, they must also translate the global business unit and global customer plans into local programs that will satisfy retailers and consumers, grow sales, and reduce costs. In addition, they provide input on local conditions for GBU strategies and plans. Recently, P&G began consolidating its country organizations into market development organizations for greater efficiency. Thus, Austria, Switzerland, and Germany are grouped, while the Benelux market organization covers Belgium, Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

Customer Business Development Teams. Finally, dedicated global customer business development teams coalesce to manage the relationship with each global retailer. With representatives across functions, business units, and countries, these teams must understand the global retail customer’s strategy, develop the joint P&G/customer business plan, and coordinate with the GBUs and the country organizations to deliver on the agreed joint customer plan. As figure 5-4 indicates, the overall team-based organization can grow complicated quickly.

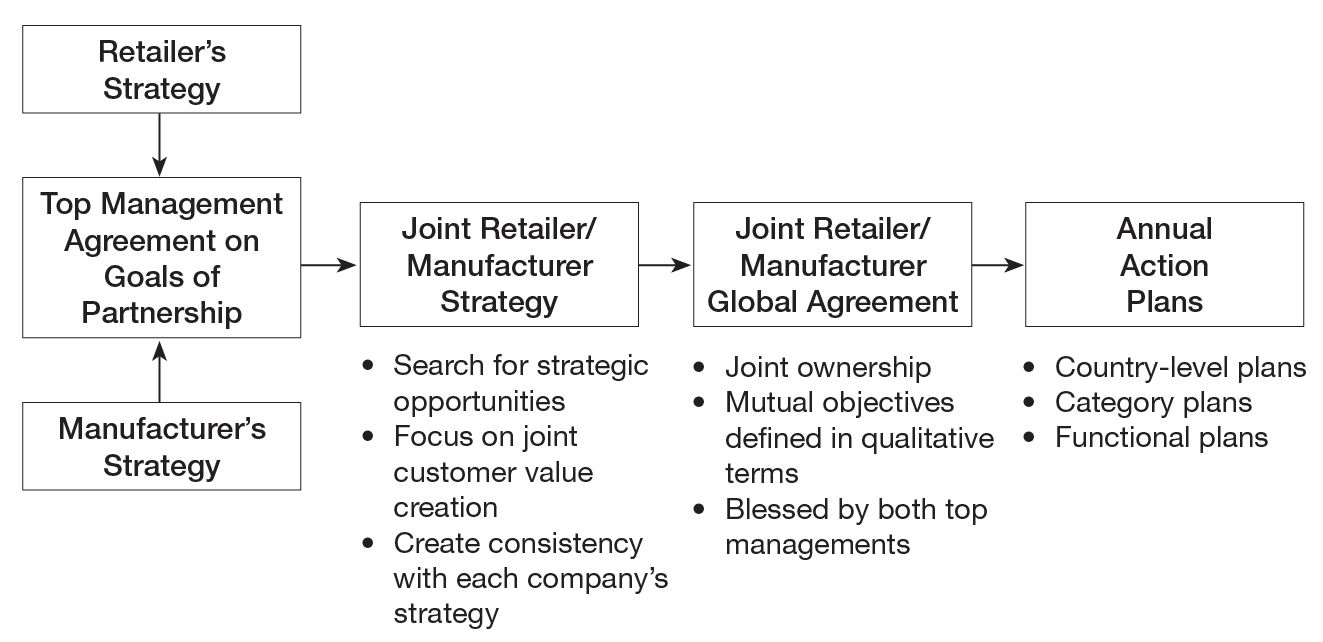

Joint Planning Processes. Planning processes in most multinational organizations still follow the traditional Army approach. The top of the organization develops strategies on brands and products, plans promotions, and presents those plans to retailers who can “take it or leave it.” With increasing retail consolidation, this top-down planning process obviously fails. Instead, manufacturers must engage retail customers in the planning process and strategy conversations, primarily to understand the goals of each other’s strategy and create a mutually agreeable joint strategy.

The planning process with a major global customer may look like figure 5-5. The global customer team must identify the three to four critical actions or initiatives that will drive business at a particular retailer, then explain these initiatives to the country organizations so that their local organizations will deliver on them.

To manage the interfaces among the customer development teams, business unit organizations, and country organizations, the manufacturer must identify and assign responsibility for all vendor activities around the global account. It must also specify which actions will be globally coordinated, partially globally coordinated, performed locally with some global coordination, or left exclusively to local organizations.30

The Organizational Structure for Global Account Management

Source: Adapted from Michael George, Anthony Freeling, and David Court, “Reinventing the Marketing Organization,” McKinsey Quarterly 4 (1994): 43–62.

Manufacturers who effectively manage global retailers do a lot of homework before their joint strategy meetings with retailers. One consumer packaged-goods company holds a two-day internal customer assessment workshop to prepare. For their Carrefour account, the workshop kicks off with thirty-three country presentations on what the company has achieved with the retailer over the past year, potential opportunities, and problems encountered. Then attendees conduct a SWOT analysis for Carrefour before engaging in an emotional discussion of what the company’s overall strategy regarding Carrefour should be over the next three years. The outcomes of this meeting are projected profit and loss statements for Carrefour at the global, country, and brand level. Thus, the global account manager can meet Carrefour armed with an internal agreement on the objectives by country and by brand.

Joint Planning Process with Global Retailers

The most effective win-win partnerships stem from mutually agreed-upon performance objectives that bind both parties. Both parties must explicitly agree on a joint scorecard that identifies the key performance indicators. For example, the manufacturer may care about penetration, average ticket, frequency of purchase, sales growth, and margin growth, while the retailer may watch out for stocks, inventory turns, margins, complete orders, sales, and shelf space management.

Usually, both parties commit to quantitative and qualitative goals. Quantitative goals typically focus on increasing the sales of all the manufacturer’s brands in their respective categories. Qualitative goals may include an international promotion, such as an in-store display, of a few brands across all countries. In return, the manufacturer may promise certain margins and support. Then, depending on the magnitude of the business, the manufacturer and retailer usually meet once a month or once a quarter to share data and monitor progress on these performance indicators.

Information Systems Transformation

In one of my earliest encounters with global retailing, I witnessed the CEO of a major multinational manufacturing company go crazy because his people could not tell him, with any degree of accuracy, how much profit they generated globally on sales to a global retailer who had just requested a single global price. According to one study, only 11 percent of manufacturers can assess the true cost of serving international retailers, despite rather sophisticated, expensive information systems.31 Most companies that measure global account profitability use standard cost allocations rather than activity-based costing, and so they cannot generate a reasonably accurate profit and loss account for a global customer.

Since then, I have interacted with a major worldwide supplier to Carrefour. The global account manager had to negotiate a worldwide deal with Carrefour but could not determine his company’s worldwide sales to Carrefour. The manufacturer’s systems yielded numbers by country and by product line, but not by customer across product lines and countries. He could have compiled the revenue numbers manually but in a couple of African countries the manufacturer sold to Carrefour through agents who would not share sales data by customer with the global account manager. So he relied on Carrefour for data on the manufacturer’s worldwide sales to the retailer. How can one negotiate if one does not have basic reliable information? It is like flying a plane without an altimeter.

Even at a sophisticated firm like P&G, the information system can provide aggregate volume data for a customer but one must manually calculate worldwide sales by customer in dollars—and only at list prices. To obtain the worldwide net sales in dollars for a customer would necessitate a rather painstaking manual compilation. Some companies like Hewlett-Packard, however, are investing in systems that can generate profit and loss statements for each global customer.32

The inability of marketers to provide financial information on marketing initiatives continually frustrates CEOs. Only 22 percent of companies in a survey monitored the effectiveness of trade promotion spending at the event level.33 As joint planning with retailers increases, information about the profitability of events is critical in establishing account-specific objectives. Information systems that support global account management should monitor worldwide sales to the retailer, calculate the global profitability of the account, provide internal forums for global account managers to share learning, and help monitor and implement specific reward and evaluation systems.

Human Resource Transformation

Four human resource issues are related to how customer business development teams dedicated to global accounts function: coordination, co-location, composition, and compensation.

Coordination. The coordination demands on the supplier’s global customer team are extremely onerous. Companies must synchronize the various functions, business units, and country organizations through common goals, information, and compensation—and that’s on top of harmonizing their marketing, sales, and service organizations to present an integrated face to local customers. Managers must not only reallocate resources across countries, product lines, and types of promotions, but also learn to collaborate internally.

Co-location. Companies often debate where to locate the global customer development team. The 150-person P&G team for Wal-Mart is located in Bentonville, Arkansas, the home of Wal-Mart. Among the advantages of such proximity to the customer’s global headquarters is the access to real human beings who can form individual relationships that roll up into a stronger partnership between the supplier and customer. One customer business development manager remarked, “Some of our teams are co-located, and some aren’t. The ones that are co-located tend to do much better [in] adversarial kinds of situations because they can communicate. When everything you touch turns to gold, you can be almost anywhere.... But when things . . . get a little rockier, co-location matters.”34

Co-located supplier teams can also focus on the customer at hand, not on other accounts and company politics. Overwhelmingly, formal and informal conversations within co-located teams are usually about the customer. Co-location fosters esprit de corps, and teams tend to develop a culture that is neither the supplier’s nor the customer’s. However, sometimes teams living near customers “go native” to the detriment of the supplier’s corporate objectives.

Composition. The composition of global account management teams is an important issue that managers often overlook. Who should lead the team? Who should participate? What skills matter? Most companies have excellent models for allocating resources to investment opportunities, but are still learning how to allocate people to teams. Currently, companies tend to select the leader from the same country as the retailer’s headquarters. For example, the leader of a team working with Carrefour would be French and have considerable experience with the retailer. However, firms are evolving on this issue. At one consumer packaged goods company, the Ahold team leader was changed from a Dutchman to an American because most of Ahold’s sales currently come from the United States.

However, many suppliers mistake customer business development teams for “sales teams” and therefore fail to incorporate logistics, marketing, finance, and other functions, as well as representatives from different countries and business units into customer business development teams.35 Sometimes companies under-resource such teams without realizing that worldwide sales to a global customer may exceed those generated by many country subsidiaries.36 For example, P&G operates in 140 countries with 300 brands. However, its six top customers, Wal-Mart and Costco (United States), Carrefour (France), Ahold (the Netherlands), Tesco (United Kingdom), and METRO Group (Germany), currently account for more than 30 percent of P&G’s sales. Its largest fifty customers account for 55 percent, and it expects that its top ten accounts will deliver 50 percent of P&G’s sales within five to ten years.

Compensation. Most companies still link customer team compensation to revenue and volume, because they can not calculate account profitability and do not care about the profitability of their customers.37 Increasingly, global retailers are asking their suppliers to take some responsibility for the retailer’s margins and profitability on the supplier’s products. One customer business development manager observed, “It’s important to recognize our accountability to customer’s measures. For years we used to say, ‘margins are not our problems, they are your problems.’ . . . Now we are saying, ‘we are accountable for that.’”38

The best way to ensure accountability is to link part of the team’s compensation to retailer profitability on the supplier’s products. In addition, suppliers are linking the team’s compensation to customer service and account profitability.

Since customer business development teams exist alongside more hierarchical country and business unit organizations, team members need specific career and development tracks, clear reporting relationships, and agreement on compensation.39 For example, the local manager managing the Wal-Mart relationship for P&G in Germany reports to P&G’s global account manager for Wal-Mart as well as the local P&G country manager. If the person does not report to the global account manager, then the company might as well not have a customer business development team. On the other hand, failing to integrate the local organizations within the global teams can lead to overall failure. So should P&G attribute sales to Wal-Mart in Germany to Germany or to the global account manager for Wal-Mart? Most companies resolve this through double counting where both managers get credit.

In non-retail contexts such as advertising or audit services, conflicts arise over compensating independent local offices for their work on global accounts. What is fair when wages vary tremendously around the world? Justifying the payment of diverse rates for the same work, for the same account, may turn into a political and cultural minefield. Companies differ in their approach: Grey Advertising sets interoffice billing rates annually, and British Telecom negotiates all local compensation before signing a global client. Other companies eliminate interoffice billing and distribute the revenues based on the percentage of each office’s work.

Companies that fail to resolve this—or any of the remaining Cs—risk alienating their most valuable long-term customers. For example, a few years ago, Citibank discovered that its country managers refused to serve multinational corporations adequately. 40 Citibank’s country organizations made relatively low margins from working on multinational accounts and country managers were evaluated on their country’s profitability. However, multinational companies represented Citibank’s best opportunity for growth by selling them high-margin global services. To solve the problem, CEO John Reed took profit responsibility away from country managers and instead rewarded them for services provided to multinational clients.

Conclusion

As distribution channels consolidate worldwide, the pressure on upstream suppliers will only increase. Their survival will likely depend on their ability to work with powerful global members of the distribution channels. Clearly, the best approach is to develop in-demand brands that distributors simply must stock and support. However, even suppliers of such strong brands must continually innovate and diligently manage their distribution channels. Suppliers in trusted reseller relationships will increase the potential for creating value for the end user by reducing superfluous processes.

Global Account Management Checklist

- Customers: Have we identified our most valuable clients on a worldwide basis?

- Strategy: Do we have a clear strategy for global accounts?

- Structure: Does our structure promote cross-border, crossdivision collaboration with global customers?

- Relationship: Are there single points of contact for global customers?

- Culture: Do we accept global account managers as advocates for global customers?

- Incentive systems: Do our compensation and incentive systems align with serving global clients?

- Talent: Do we have enough people who can serve on global account teams?

Suppliers cannot adopt a one-size-fits-all approach with distribution channels. Some retailers will work together in partnerships, while others prefer adversarial relationships. Firms must simultaneously optimize the power and trust games with different retailers. Similarly, suppliers will have both global accounts and traditional accounts, but those that develop real competence in global account management will observe reductions in cost of sales, revenue growth, higher cross-selling of products from weaker divisions, greater sales force efficiency, easier launch of new products, and increased responsiveness to customer-specific needs at the account level.

- Process: Have we synchronized our processes with those of global customers?

- Competence: Can all of our country organizations perform at global service levels?

- Supply chain: Have we optimized our supply chain for global efficiency?

- Marketing: Have we successfully implemented brand and SKU rationalization initiatives?

- Pricing: Have we harmonized prices/pricing structures?

- Accounting systems: Do our customer-level worldwide profit-and-loss statements go beyond standard cost allocations?

- IT systems: Do our IT systems generate the needed data on global customers?

- Knowledge management: Are we effectively utilizing global customer data to develop new products and improve weak positions in existing products?

Adapted from Christopher Senn, “Are You Ready for Global Account Management,” Velocity, no. 2 (2001): 26–28.

Managers who answer “no” to any of the questions in the “Global Account Management Checklist” need their CEO’s support to effect the necessary changes. Consider Electrolux, a company that has assembled a vast brand portfolio through acquisitions over the years. Suspicious business unit managers are hampering efforts to coordinate across different units to serve global customers such as hotel chains or Shell Oil.41 Similarly, the more entrepreneurial ABB struggled to serve global clients until Goran Lindahl became CEO and underscored the importance of global account management.

Over time, global customers will start to account for a majority of the supplier’s sales with their own global customer development teams. As companies organize around customers, they will consolidate sales and marketing functions, eliminate national offices, and cut back or downgrade central marketing departments. These customers’ teams will increasingly perform more of the marketing activities, and their leaders will likely report to the CEO, or a Chief Customer Officer, who reports directly to the CEO. Anyone still called the Director of Marketing or the Director of Sales will probably report to the Chief Customer Officer.

The ultimate Chief Customer Officer is the CEO, who will serve as ambassador to the large global accounts and intervene on issues that the team leaders cannot resolve.