SIX

From Brand Acquisitions to Brand Rationalization

Don’t advertise the brand, live it.

IN THE KNOWLEDGE AGE, CEOs realize that the value of their firms is determined less and less by the tangible assets they own, such as factories or inventories, and increasingly by intangible assets such as competences, customer base, distribution networks, employees, and brands. Of all the intangible assets owned by a company, brands are perhaps the most prized. This has led to a dramatic change in how CEOs view their companies, their sources of competitive advantage, and their notion of the firms’ strategic assets. In 2000, Niall FitzGerald, cochairman of Unilever, declared: “We’re not a manufacturing company anymore. We’re a brand marketing group that happens to make some of its products.”1 This from a company that until the mid-1970s derived more than half its profits from its African operations, which included retailing, shipping lines, and trading, as well as plantations producing bulk vegetable oils for margarine and washing powder!

Branding should be the differentiating mechanism, separating the company’s products and services from those of its competitors. If done correctly, it allows the seller to escape the commodity magnet, where price and product features are the primary differentiators. A strong brand helps generate greater sales and price premiums. Brand equity should be a rich reservoir of goodwill for the company, making it easier to attract customers, dealers, employees, and investors. As custodians of the brand value, nothing should be as sacred, as precious, to marketers as the brands they manage.

Buying a brand and its market share is often much cheaper and faster than building it. Companies such as Akzo Nobel, Cisco, L’Oreal, and Nestlé have been consolidating their positions by acquiring smaller players. In addition, there have been many megamergers between large companies within the same industry, such as Citigroup-Travelers, DaimlerChrysler, Exxon-Mobil, or Hewlett-Packard and Compaq. As a result of these brand mergers and acquisitions, many companies find themselves with large brand portfolios. In 1998 in Europe alone, Akzo Nobel sold paint under thirty-seven different brand names including Astral, Berger,

Casco, Crown, Marshall, Nordsjö, Sadolin, and Sikkens.2

Assessing their brand portfolios, top managers worry that many of their brands are serving only small niche segments with few customers, thereby generating insignificant revenues or profits. Consider the following:

- Of its 250 brands, P&G’s top ten brands, including Pampers, Tide, and Bounty, account for half of its sales, more than half of its profits, and almost two-thirds of its growth over the past decade.3

- The bottom 1,200 brands in Unilever’s 1,600-brand portfolio accounted for only 8 percent of the company’s total sales in 1999.4

- The vast majority of Nestlé’s profits come from a tiny percentage of more than 8,000 brands worldwide.

In the face of such large brand portfolios, companies are now killing off famous names rather than acquiring and extending brands, as was the rage over the last two decades. Many famous brands are dead or dying. GTE and Bell Atlantic are now Verizon; General Motors has finally retired Oldsmobile; Merrill Lynch has dropped the Mercury brand; and Citibank—now Citi—has deleted Schroders and Solomon. In the consumer packaged goods industry, historical brands such as La Rouche-aux-Fées yogurt in France, Treets candy in the United Kingdom, and White Cloud toilet paper in the United States have received their pink slips. Such firms as Akzo Nobel, Diageo, Electrolux, P&G, and Unilever have rationalized or are actively rationalizing their brand portfolios. And more companies keep jumping on this bandwagon. For example, Shiseido recently announced plans to cut its brands from 140 to 35 by 2005. The dilemma for companies is to prune their brand portfolios without losing the customers and sales revenue associated with the brands that are to be deleted.

Brand Proliferation Is Costly

Finer market segmentation clearly warrants some brand proliferation. However, mergers and acquisitions, as well as uninhibited brand propagation aimed at alleged market and growth opportunities, account for a fair share of the mushrooming. To justify its existence, each brand in the portfolio must link to a specific target segment and have a unique positioning. The cost of maintaining each individual brand in the portfolio must be less than the revenues that it generates through greater segmentation. The ten questions presented in the following box help managers to determine whether their company has too many brands.

Managing mammoth multibrand portfolios, especially within the same product category, presents the following major problems.

Does Your Company Have Too Many Brands?

- Are more than 50 percent of our brands not featured amongst the top three brands in terms of market share?

- Are there brands for which we are unable to match competitors on marketing and advertising expenditures because we lack adequate scale?

- Are we losing money on our smaller brands?

- Do we have different brands in different countries for essentially the same product?

- Are there brands in our portfolio that display a high degree of overlap on target segment, product lines, price bands, or distribution channels?

- Does the analysis from image tracking surveys, closest competitor studies, and consumer brand switching matrices demonstrate that customers see our brands as directly competing with each other?

- Are retailers only agreeing to stock a subset of our total relevant brand portfolio?

- Are there brands in our portfolio where an increase in marketing and advertising expenditures in support of one of the brands decreases the sales of another brand in the portfolio?

- Do we spend an inordinate amount of time discussing resource allocation decisions across brands?

- Do our brand managers see each other as competitors?

Score 1 point for each question answered with a “yes.”

0–2: Minimal brand rationalization opportunity.

3–6: Considerable brand rationalization opportunity.

7–10: Brand rationalization should be an immediate priority. Alert top management.

1. Insufficient Differentiation

The greater the number of brands within a particular category, the more challenging for the firm to position each one uniquely. Only so many distinctive combinations of benefits and attributes will attract substantial numbers of customers. How well has, say, General Motors differentiated the product lines and brand images of its car brands: Buick, Cadillac, Chevrolet, Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Opel, Saab, and Saturn?

Not surprisingly, the larger the number of brands in the company’s portfolio, the greater the overlap of brands on target segments, positioning, price, distribution channels, and product lines. The overlapping results in cannibalization of sales and duplication of effort. If managed poorly, many of the brands in the portfolio may end up competing with each other rather than with competitors’ brands.

2. Inefficiency

Invariably, a larger brand portfolio means lower sales volumes for the individual brands as the total market divides among them. Without scale economies in product development, supply chain, and marketing, firms cannot support each brand at competitive levels. For example, developing a new model in the automotive industry takes almost a billion dollars in development costs and production investments. Without adequate resources to refresh each brand’s product line, companies such as General Motors and Volkswagen share product platforms across brands. While this practice increases efficiency, it lowers perceived product variety. According to critics, Volkswagen’s sharing of product platforms across brands (for example, the chassis shared between the Volkswagen Beetle and the Audi TT) has diluted the more prestigious brand and reduced differentiation.

Similarly, companies must spend a minimum amount annually on marketing and advertising each brand to attract customer attention, and this amount has been rapidly rising over the years. For example, in 1995, three television advertisements could reach 80 percent of women in the United States; today a company must buy ninety-seven spots to reach the same audience .5 Thus, small brands sweat to remain competitive. As Unilever’s FitzGerald observed, “You need to get through the clutter of communication with consumers and if you spread your budget over all your brands, it doesn’t get through. We will have to swing our resources behind a smaller number to achieve higher growth rates for them.”6 Managers often allocate the multibrand firm’s brand budget suboptimally, thereby reducing the corporate return on brand investments.

3. Lower Market Power

The rise of powerful mass merchants such as B&Q, Barnes & Noble, Best Buy, Carrefour, Home Depot, and Wal-Mart has triggered brand consolidation perhaps more than anything else. The retailers’ tremendous negotiating power, especially against weaker brands, forces manufacturers to critically evaluate their brand portfolios.

Large retailers have also developed top-quality store brands that currently account for one in five units sold in U.S. stores and about twice that in Europe. Retailers have used these store brands to play manufacturers off each other. Many retailers will carry only the top two or three manufacturer brands in a category plus their own private label. Weaker manufacturer brands either lose their shelf space to store brands or else pay dearly to retain it. Hans Straberg, CEO of Electrolux, stated, “Our aim is to become a reliable and trusted partner with our customers and retailers. That means we need a few strong brands. We can’t support too many.”7

4. Management Complexity

Finally, brand proliferation pressures management to coordinate the complicated and larger portfolios of products, package designs, R&D projects, marketing plans, and distributor relationships. Marginal brands end up consuming a disproportionate amount of a company’s time and resources, and exacerbate tensions between the narrowly focused brand and country managers. In annual marketing strategy and budget meetings, top managers find themselves focusing internally on resource allocation across the different brands, rather than externally on battling competitors and serving customers.

The Forces Behind Brand Consolidation

| Past | Future | |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate | Acquisitions and mergers | Search for synergy |

| Search for top-line growth | Search for profitable top-line growth | |

| International expansion | Global strategy | |

| Brand-management structures | Category-management structures | |

| Power of country managers | Corporate HQ resistance | |

| Competition | Copycat strategies | Need for differentiation |

| Worldwide deregulation and mushrooming media outlets | Emergence of global media giants | |

| Channel/ Consumer | New distribution channels | Consolidating distribution channels |

| Demand for exclusive products and shelf space productivity | Demand for category management | |

| Desire to avoid channel conflict | Growth of private labels | |

| Multiple consumer segments | Cross-national segmentation | |

| Local marketing | Emergence of global consumers | |

| Growing Brand Portfolios | Shrinking Brand Portfolios |

CEOs are distressed to discover that their most valuable asset, the burgeoning brand portfolio, is devouring company profitability and hampering growth. Moreover, the surge in global media, global segments, and international distributors all reduce the logic behind many brands that were unique to single countries (see table 6-1). CEOs see the wisdom in fewer, larger, and more global brands and realize that brand rationalization provides a critical path to higher profitability and growth.

The Challenge of Brand Rationalization

Deleting brands is easy, but retaining their sales and customers is not. Therein lies the managerial dilemma: How can brand portfolios be pruned without losing the customers and sales revenue of the doomed brands?

Overwhelmingly, firms lose market share, sales volume, and customers to their competitors during brand portfolio rationalization. To stem such losses, managers often try to merge two brands instead of deleting one. Still, studies indicate that only one in eight attempts to consolidate two brands ever delivers the original market shares of the two brands. Consider the following failures:

- Kal Kan and Crave, two of the three leading brands in the U.S. cat food business in the 1980s, merged in 1988 to create a new brand called Whiskas .8 Five years later, Whiskas had still failed to reach the combined market share of Kal Kan and Crave. To salvage sales, Kal Kan Foods, Inc., finally reintroduced the Kal Kan name on the Whiskas packaging but with limited success.

- In 1987, Mars, Inc., merged the brand Treets, a European candy quite unlike M&Ms, into the M&Ms brand without warning customers.9 M&Ms suddenly came in two packages, containing very different products, neither of which enticed British and German palates. Sales dropped 20 percent in the first year. In 1991, Mars reintroduced Treets in Germany, as M&M’s Treets Selection.

- In 1996, Rite Aid Pharmacies acquired the 1,000 Thrifty/ PayLess drugstores, a western U.S. regional chain, and converted them all to Rite Aids. To raise local awareness about the new brand, Rite Aid invested several million dollars in advertising the rebranded chain. However, Rite Aid executives underestimated the value of Thrifty/ PayLess’s walk-in business, attracted by a product mix that included “award winning” ice cream, beach balls, cosmetics, and magazines. Rite Aid struggled to recapture former Thrifty/PayLess customers who did not equate pharmacies with such impulse buys. Immediately after the rebranding, the acquired stores’ sales started declining 10 percent monthly. In 2000, Rite Aid hired two former Thrifty/PayLess executives to manage its western region.

- In 1999, Hilton International acquired four-star U.K.based Stakis (fifty-four hotels and twenty-two casinos) for £1.5 billion and then killed the Stakis brand. The overnight name change confused and disappointed Hilton International guests, who found that some of the newly acquired hotels did not meet their expectations of the Hilton brand. Despite claims of spending £100 million to upgrade standards to unify its hotels under the Hilton brand, sales fell 6.6 percent in 2000. So, in 2001, when Hilton acquired Scandic’s 154 hotels in the Nordic region, it wisely retained the Scandic brand and rebranded only twenty of the properties under the Hilton name.

Brand rationalization hurts. Remember that even weak, money-losing brands have devoted channel members, customers, and prospects—not to mention brand and country managers—who will vigorously defend them. A proposed brand deletion could endanger a distributor’s or employee’s livelihood, if not a lifetime of commitment to the brand. What will that familyowned Oldsmobile dealership do if General Motors does not offer a replacement brand from its portfolio?

Brand rationalization is neither straightforward nor well understood. No one can easily determine which brands to retain, merge, sell, or delete altogether in a portfolio, and no marketing textbook covers the decision-making process. Without clear methodology and an actively engaged CEO, strategy sessions will likely suffer from politics and turf wars. Antony Burgmans, cochair of Unilever N.V., observed in a meeting with top executives, “Focusing the brand portfolio is the single biggest issue facing Unilever today. This is not something we can delegate to others. It is too important. We have to do it ourselves—quickly.”10

The Brand Rationalization Process

Based on the experiences of several successful firms, a shrewd brand rationalization process has four essential steps: (1) Conduct a brand portfolio audit; (2) determine the optimal brand portfolio; (3) select appropriate brand deletion strategies; and (4) develop a growth strategy for the survivors. Managers who plunge directly into brand rationalization (steps 2 and 3) without preparing the organization (step 1) or outlining a growth strategy (step 4) will fail.

Conduct a Brand Portfolio Audit

To succeed, a brand rationalization program must win the support of front-line managers. Managers, especially of the brands targeted for deletion, often fear brand rationalization because they fear losing their independence and drowning in the larger company. This anxiety leads them to overstate the downside of eliminating the brand. To enable an unbiased decision, the brand rationalization program should first conduct a brand portfolio audit.

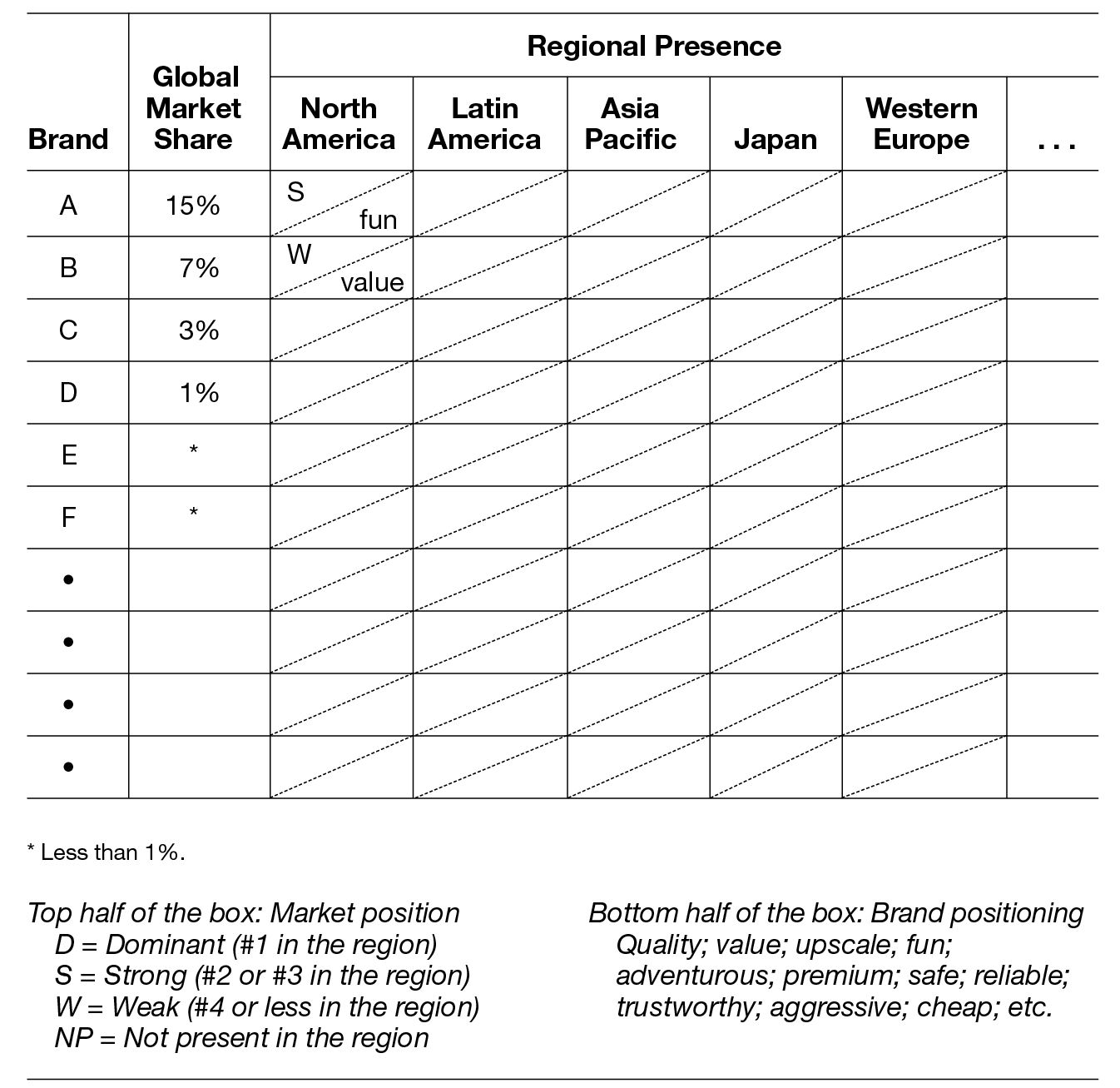

The brand portfolio audit objectively exposes managers to the corporate perspective on the portfolio. The audit raises issues concerning positioning overlap, synergies, and benchmarking, which help country and brand managers see the big picture. Without such an audit, these managers could make a case to justify the existence of every brand. But the goal is to optimize the portfolio, rather than optimizing each brand in the portfolio. Table 6-2 provides a template for a brand portfolio audit. Initially, groups of managers complete the audit independently, and then pool their data. The audit identifies the brands and their global market share. Geographic or other segment markets fall along the columns. For each brand in each market, managers enter two pieces of information: (1) the market position—characterized as “dominant,” “strong,” “weak,” or “not present in the region”—to denote brand strength in the specific market, and (2) a single-word description of the brand positioning to indicate the brand’s value proposition. Examples of frequently used words appear in the exhibit, but participants are usually quite creative when completing this column.

Brand Portfolio Audit

Managers can add columns that track the percentage of corporate profits that each brand generates and whether the brand is a cash generator, cash neutral, or a cash guzzler if data are available prior to the exercise. Without hard data, however, these additional two columns can spark long internal debates that detract from the process. Better to use best guesses and verify data later. Remember, brand deletion is an art, not a science.

Obtaining detailed brand-level profitability numbers requires complex allocations of fixed and shared costs, and thus the validity of the resulting data is uncertain. The current profitability of a brand is not the ultimate indicator of which to delete. More important, the brand rationalization decision is strategic: Managers must consider what could occur, not what is actually occurring . They must imagine the profit and loss for the firm and each surviving brand after the purge of marginal brands and the adjustment of the marketing mix for survivors.

Frequently, the results of the data pooling surprises managers: Very few of the company’s brands in any category enjoy global market shares greater than 1 percent. Group discussion generally moves through various reasons for sparing pet brands to more balanced observations that many brands in the corporate portfolio

- have small market shares,

- suffer from poor or negative profitability,

- consume rather than contribute to cash flow,

- lack support from important channel members,

- exhaust disproportionate amounts of managerial resources, and

- add little strategic value to the firm.

The audit makes the need for brand portfolio rationalization apparent, impersonal, and broad-based. Top management can use it to outline the remaining three steps of the rationalization program.

Determine the Optimal Brand Portfolio

Companies utilize two complementary processes—the overall corporate portfolio approach and the needs-based segmentation approach—to determine the optimal portfolio.

The results of the brand portfolio analysis feed directly into the overall corporate portfolio approach, a relatively top-down process that sets the overall objectives and direction for the rationalization program. It broadly attacks the company’s brand portfolio using a few simple figures such as minimum sales, market share position, growth rate, and geographical reach. The outcomes of this process usually address the following critical questions:

- How many brands should we retain and how many should we delete? For example, the top managers of one company decided that they would delete all brands that were neither number one or two in terms of market share. Unilever determined that it would scrap the bottom 1,200 of its 1,600 brands—accounting for only 8 percent of the company’s sales within five years.

- What is the role of our corporate brand? For example, Electrolux decided to develop its corporate name into the master brand—the brand that would ultimately account for 70 percent of the group’s revenues.

- Which brands are core to our company? For example, P&G’s “core” brands are the twelve that each generate more than a billion dollars annually in sales.

- Does our portfolio contain any potentially global brands? Unilever, for instance, designated forty brands as core global brands.

- Should our company exit any category wherein all our brands are poorly positioned?

Answers to these questions should help articulate a vision of where, in terms of geographies and businesses, the company wishes to compete.

The needs-based segmentation approach examines the number and types of needs-based segments that exist within each individual category in which the firm competes. The results of this analysis complement the overall objectives and direction of the brand rationalization program identified by the corporate portfolio approach. Since a company must position every brand against a unique segment of consumers, this bottom-up process helps managers to determine the optimal brand portfolio in terms of individual categories and implementation.

Consider these questions:

How many distinct brands can we support in a category?

Which segments should the company cover with its brands?

Which brand should we match against which segment?

Which brands should we merge?

Since one could begin with needs-based segmentation to determine the number of brands to retain and the number to delete, this approach works well for companies where managers want to rationalize a group of brands that compete in the same category. It also helps companies that compete in many categories to select which brands should remain in particular categories where they have too many brands. For example, P&G rationalized its laundry detergents portfolio and consequently decided to merge Solo with Bold.

On the other hand, if companies with complex brand portfolios—that is, hundreds of brands across multiple categories— tried to rationalize their entire brand portfolio at once, then the data gathering and objective setting of the bottom-up approach would take too long. Better to start with the corporate portfolio-based approach to determine the overall objectives and direction and then move to the needs-based segmentation approach.

Select Appropriate Brand Deletion Strategies

Four possible scenarios exist for the doomed brands: sell, milk, delist, or merge. Companies should sell non-core brands that will not likely become competitors but could offer value to others. For example, in 1999, Diageo sold Cinzano vermouth and Metaxa brandy to concentrate on nine core brands that yielded 70 percent of its profits.11

Companies should milk for profits those brands that have some customer franchise but are neither core to the firm’s direction nor valuable to others. Milking entails stopping all but the absolute minimal marketing support, thereby increasing profits in the short run (by cutting costs) as sales slowly decline. When they finally die, the company delists them.

Companies can safely delist, or eliminate, minor brands with poor sales that grapple futilely for shelf space. To migrate loyal customers, a company can issue them coupons or samples for the most adjacent surviving brand in the portfolio.

Finally, companies can merge two brands into one if the lesser brand is still maintaining significant sales in a core category. Merging, sometimes referred to as brand transfer or brand migration, reduces the number of brands without losing sales because marketing migrates the associated customers to the surviving brand.

Depending on competitive and corporate pressures, companies choose between adopting a “quick change” versus a “gradual brand transfer” strategy. A quick change with a new brand name works when managers want to break cleanly from the past, as was the case for Sandoz and Ciba-Geigy, now called Novartis. After a painful merger, a completely new name can signify egalitarianism, resilience, and fresh opportunity. It can also convey to customers the availability of new capabilities.

Instead of developing a new name, the merged companies can quickly drop one brand, as the two Swiss banks UBS and SBS did in becoming UBS. This move works when global competition requires speed and control over customers for easy migration or when one brand is significantly stronger than the other and can extend its equity while internally signaling the direction of the new enterprise.

If both brand names have strong brand franchises, then one can adopt a gradual brand migration strategy by subbranding or dual branding during the transition before eventually dropping the weaker name. For instance, Dulux Valentine dropped Valentine, and Philips Whirlpool dropped Philips. Gradual brand migration works when markets are stable or customer loyalty to the brands is strong, as long as companies have mapped a careful migration path from the doomed brands to the survivors.

Consider Vodafone, a company formed through acquisition of equity stakes in disparately named mobile operators in various countries. In 2000, it launched a global brand migration plan to switch its constituent operating companies to its master brand by early 2002. It managed the migration in two steps. First, the individual country brands converted to dual branding, such as D2 Vodafone in Germany, Omnitel Vodafone in Italy, Click Vodafone in Egypt, and Europolitan Vodafone in Sweden, to raise brand awareness for Vodafone through the name recognition of the local brands. Next, over two years, it phased out the local prefixes in advertising campaigns and sponsorship programs. Brand tracking studies helped marketers to time the switch from the dual brand to the Vodafone master brand, country by country, when Vodafone recognition reached a certain height. For example, Portugalbased Telecel Vodafone converted to Vodafone three months ahead of schedule because of its successful dual branding program. By adopting a single brand, Vodafone’s European subsidiaries obtained cost synergies on brand advertising, media buying, global product/service branding, and advertising, while making it easier to increase customers’ usage of Vodafone products and roaming services.

Develop a Growth Strategy for the Surviving Brands

Brand deletions are risky. Without a strategy to grow the remaining brands, all the firm ends up with is a cost reduction program and a smaller top line because of the sales lost from the deleted brands. As part of the process, managers must identify opportunities to build fewer, stronger brands though enhancements and investments.

Brand enhancement involves migrating useful characteristics from the deleted brands to the remaining ones. This can be done in several ways: (1) The deleted brand may have one or two unique or attractive products that could do well under a surviving brand’s product line. (2) Some attribute of the deleted brand could resurface in a surviving brand to augment the latter’s value proposition. (3) Surviving brands may lack presence where a deleted brand was sold. Replacing the defunct brand with a survivor in that locality will expand its geographical footprint.

Brand investment purposefully redirects the resources freed from the discontinued lines to the surviving brands. By merging brands, companies can generate substantial savings through greater economies of scale in supply chain, sales, and marketing. A more streamlined product line and better inventory optimization may reduce cost of goods sold, and combining the brands’ respective sales forces and customer service teams may cut sales and administration expenses. Finally, focused marketing and advertising can generate greater bang for the buck. For example, by concentrating on the fourteen of the three-hundred-odd brands that account for more than half of P&G’s sales, A. G. Lafley, the current CEO, increased turnover in ten, including Crest toothpaste, which grew by more than 30 percent.

Bottom-Up Segmentation-Based Approach at Electrolux

Electrolux, based in Sweden, is one of the world’s leading consumer durable products companies. Its products include white goods, such as refrigerators, cookers, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and outdoor equipment like mowers, trimmers, and chain saws. Over the past twenty-five years, the company has made between three and four hundred acquisitions, resulting in a very large brand portfolio.

Under CEO Michael Treschow, the company cut costs with modest success through plant rationalization and a reduction in the number of product platforms. In 1998, Electrolux examined its portfolio of over seventy brands. It discovered that, in almost every country, one of its brands was among the top three, but it was never the same brand across borders. Not surprisingly, the company’s fragmented marketing efforts could not achieve economies of global scale or scope.

The brand portfolio’s complexity raised a fundamental question about Electrolux itself: Was it a manufacturing company that should just let retailers and others build brands, or was it a branding company? Ultimately, the firm’s board of directors favored the latter, and the firm launched a brand rationalization project to create fewer but stronger brands.

The name of the company, Electrolux, would become the master brand. By phasing out weak local brands and having Electrolux endorse strong local brands, executives resolved to generate two-thirds of the company’s sales from its master brand by 2007. Within this overall rationalization program, Electrolux’s effort in one category—the professional food service equipment business—richly illustrates the bottom-up segmentation-based approach.

In 1996, Electrolux had a 4.2 billion Swedish Kroner (SEK) business selling food service equipment across Europe to professional kitchens in hospitals, restaurants, airports, and cafeterias.12 The European food service equipment market was highly fragmented, with fifteen to twenty-five competitors per country, and little overlap among the players across countries.

Over the years, Electrolux bought several small individual companies, each of which had a brand and a factory. By 1996, more than fifteen different Electrolux brands (including Molteni in France, Senking in Germany, CryptoPeerless in the United Kingdom, and Nordton in Italy) clamored for Europe’s food service equipment business. Only one brand, Zanussi, had a pan-European profile. Given so many local brands, Electrolux ran a decentralized business. The small size and weak coverage of the fifteen individual brands meant that Electrolux was losing money overall with operating losses of 1.3 percent in its food service equipment business in 1996. An Electrolux survey demonstrated that leading brands generate higher price premiums. Hence, brand rationalization in food service equipment became central to restoring profitability and sustaining the company’s overall strategic direction: Reduce the number of brands and strengthen the remaining few.

In order to eliminate brands, Electrolux had to decide how many brands it should have in food service equipment. It conducted a major cross-national, needs-based segmentation study to inform this decision. Similar to many other professional markets, the food service equipment industry segmented the market into “low,” “medium,” and “high” according to price and product specifications. Brands tended to target one of these segments by claiming to be good, better, or best. Electrolux positioned its brands across these three price bands and segmented further by customer profile, such as hospital, canteen, bar, school, convenience store, restaurant, and hotel.

This study pinpointed two problems with the conventional industry approach to segmentation:

- Customer type did not really predict customer needs. For example, restaurants varied significantly in terms of needs; lumping all restaurants within one segment made little sense. No institution was “average.”

- Each customer sought the best solution for that customer’s needs. Why should customers want a good or a better brand rather than the best for their purposes?

Electrolux realized that developing the best solution for each customer required starting from customer needs. The pan-European needs-based segmentation study revealed four distinct segments across countries. Furthermore, each of the four segments had different customer types, product specifications, pricing indexes, distribution needs, and contexts in which customers used the equipment.

The “performance specialization” segment, comprising firms such as airlines, five-star hotels, and hospitals, produced large volumes of meals under circumstances that involved complicated logistics. Customers needed high performance, integrated systems, and a price index of 100 compared to the other segments.

The “basic solution, fast return on investment” segment, consisting of firms such as pubs and convenience stores, used catering as an auxiliary activity geared to generating fast ROI through basic menus. Customers sought conformity with legal and sanitary regulation and very low prices (price index of 25).

The “gastronomy partnership” segment, comprised of firms such as staff canteens, family restaurants, and elderly homes, produced fewer than two hundred meals daily in a normal environment and had low technical competence. Customers required modular solutions, close supplier relationships, and proven technology at reasonable prices (price index of 50–75).

The “prestige gourmet” segment, consisting of gourmet restaurants, independent or within five-star hotels, with celebrity chefs who produced signature dishes. Customers wanted to create a prestigious kitchen—with a very reliable stove—as a status symbol (price index of 200–300).

Electrolux decided that, in the short run, it would forgo the second segment because of the prevailing low prices, fragmented customer base, and lack of an appropriate product range. Instead, it would target the other three segments with unique brands that focused on fulfilling the particular segment’s needs. Since it needed only three brands, Electrolux chose the brands Electrolux, Zanussi, and Molteni to serve the performance specialists, gastronomic partners, and prestige gourmets, respectively. Managers arrived at these three brands based on scale and proximity to the desired positioning of the respective target segment.

After the segmentation and deletion, division managers decided that each of three brands should invest in building a brand image appropriate to the target segment. Electrolux used a fivelayer brand pyramid to examine each brand’s personality, values, rewards, functional benefits, and features.

Thanks to its brand rationalization program, Electrolux now has three pan-European brands smartly positioned as the best for each needs-based segment. Two of the remaining twelve brands, Juno and Therma, had pockets of strength and were temporarily converted into subbrands of Electrolux, while the other ten brands were eliminated.

Three robust pan-European brands instead of fifteen local brands enabled Electrolux to centralize brand management. For consumers to perceive each brand as the best solution for their target segments, Electrolux developed a number of international marketing and communication tools including new advertising concepts, Internet and extranet sites dedicated to the brands, customized commercial documentation, newsletters, road shows, and exhibition and showroom concepts. Most local brands could not have developed these tools due to the costs and competence requirements.

Since managers understood the needs-based segments explicitly, they could develop fewer but more appropriate products for customers. Twice a year, about twenty of the one hundred designers and engineers from the European product development centers work three days alongside restaurant staff in hospitals, hotels, and office canteens.13 This on-site research unearths useful insights, such as simpler ways to clean the equipment. The needs-based segmentation has also helped the division to redefine itself from an engineering company to an “orchestrator of gastronomic events.” In fact, Electrolux insists that all divisions use a needs-based segmentation approach to new product development.

The resulting economies of scale and scope have turned the fortunes of the professional food service equipment business at Electrolux. Its operating income has increased by almost 10 percent, from negative 1.3 percent in 1996 to positive 8.1 percent in 2001—an increase in the bottom line of 390 million SEK.

Electrolux has largely managed to retain sales at 4.2 billion SEK between 1996 and 2001 despite deleting twelve brands. Its next challenge involves increasing revenues by investing substantially in marketing these three brands and targeting the initially ignored fourth segment with a new brand, Dito.

Top-Down Portfolio-Based Approach at Unilever

In 1999, Unilever, the Anglo Dutch consumer products giant, suffered its third straight year of declining revenues. After a 6 percent increase in 1996, revenues had declined by 11, 9, and 0.2 percent respectively in 1997, 1998, and 1999 to a worldwide total of £27 billion. In the 1990s, the underlying annual sales growth of 3 to 4 percent was below the firm’s aspiration of 5 to 6 percent. Operating margins at 11 percent, while healthy, were still unacceptable to management. The pending acquisition of U.S.-based Bestfoods in 2000 would bring additional brands such as Hellmann’s and Knorr.

On examining its worldwide portfolio of 1,600 brands, the top management discovered that the 400 core brands generated 75 percent of the firm’s revenues; the other 1,200 brands contributed only 8 percent. Managers agreed to pursue radical steps.

Unilever embarked on a five-year program, “Path to Growth,” that would stress the 400 core brands and, more dramatically, dispose of, delete, or consolidate the remaining 1,200 marginal ones. This strategy had two objectives: (1) increase annual sales growth to the 5 to 6 percent range and operating margins to 16 percent plus by the end of 2004, and (2) generate earnings per share growth over the period of the plan in the low double digits.

First, Unilever developed a process for identifying the 400 core brands. It set the following three selection criteria:

- Brand scale: The brand must have adequate scale and margins to justify further investment in communication, innovation, and technology at competitive levels.

- Brand power: The brand must have the potential to be number one or two in its market and be a must-carry brand to drive retailers’ store traffic.

- Brand growth potential: The brand must have the potential for sustainable growth based on current consumer appeal and ability to meet future needs. Unilever favored brands that tapped into global consumer trends (for example, health and convenience) and could potentially stretch across categories. For example, it repositioned Bertolli from Italian olive oil to Mediterranean-inspired food.

Managers established an iterative process whereby each regional brand team proposed candidates for inclusion in the core list, then negotiated with the corporate center. Through this process, the core 400 brands were identified. Since different brand names in different geographies sometimes had similar positioning and innovation, these 400 actually occupied only 200 distinct brand positions. In other words, Unilever had only 200 core brands, 40 of which were global—such as Dove, Flora, Knorr, Lipton, Lux, and Magnum. Another 160 brands, such as PG Tips and Marmite, became “local jewels,” strong in a particular region or country.

Brand rationalization efforts succeed only when companies grow the top and bottom line by focusing intensely on the remaining brands. On its “Path to Growth,” Unilever had to invest disproportionately in the core brands on four fronts—advertising and promotion, innovation, marketing competence, and management time—financed through two sources. First, it reallocated resources from the 1,200 non-core brands to the 400 core brands. For example, Unilever reassigned innovators and brand marketers once responsible for non-core brands to the core brands, and redirected more than 500 million euros of annual advertising and promotion money to the core brands. Second, Unilever attacked costs. Brand rationalization sparked a restructuring plan that entailed closure of 130 of its 380 factories worldwide; 113 have already been shuttered. Unilever also set out to reduce the 330,000-person global workforce by 10 percent in five years. When combined with the additional savings from consolidated purchasing power and shared services, annual savings through procurement (1.6 billion euros) as well as supply chain restructuring and simplification (1.5 billion euros) yielded approximately three billion euros.

Unilever directed some savings toward improving the bottom line to meet the operating margin target. However, Unilever decided to increase the marketing and promotion expenses from 13 to 15 percent of sales—more than a billion euros a year of additional marketing support—during the five-year period. Combined with the 500 million euros redirected from non-core brand marketing, the core 400 would get more than 1.5 billion euros of additional annual investment by 2004. Given the high levels of marketing support that most brands receive in the consumer packaged goods industry, managers determined that only such a substantial shift in resources would discernibly affect the marketplace.

For each of its core brands, Unilever systematically searched for, and continues to seek, unexploited growth opportunities. It begins by reviewing current positioning as well as related competitive intelligence and consumer insights. It seeks avenues for growth by asking how the brand can:

- reach new customers,

- launch new products and services,

- develop new delivery systems,

- penetrate new geographical markets, and

- generate new industry concepts.

As figure 6-1 illustrates, identifying growth entails a significant switch from a category to a brand mind-set. Knorr can springboard across categories from its dry soup brand heritage.

In some cases, such as with Dove, managers conducted brand growth sessions and dubbed the results “three horizons of growth”:

- Extend and defend core business—to achieve within the next two years (for example, moving Dove into eighty-four countries)

- Build emerging business—to occur in the two- to three-year time horizon (for example, launching Dove deodorants)

- Create options for the future—usually to accomplish in the three- to five-year time horizon by setting up a new team and developing competences currently lacking at Unilever (for example, the creation of Dove spa)

Each of the 1,200 non-core brands, designated the “tail,” were sentenced to one of the following four strategic fates:

- Sell the brand. Unilever put up for sale those brands in categories outside its core. In 2000, it sold the Elizabeth Arden cosmetics and fragrance business to Miami-based FFI Fragrances; in 2002, it sold Mazola corn oil and eighteen related brands to ACH Food Companies, Inc., a subsidiary of Associated British Foods plc. By 2003, Unilever had divested eighty-seven businesses for 6.3 billion euros.

- Milk the brand. Unilever allowed non-core brands with sufficient brand equity to linger so that it could “milk” them by sacrificing sales growth for greater profits. These brands received in-store marketing only, no advertising, and its marketers were reassigned to the core brands.

- Delist the brand. Managers eliminated small brands such as Rosella Ketchup in Australia and Dimension Shampoo in Brazil while reallocating their shelf space to more profitable brands in the portfolio. Category managers helped to develop a program to migrate their customers to similar brands in the Unilever portfolio so that Unilever would retain its overall market share in the category.

- Migrate the brand. The attributes of non-core brands that could enrich a core brand were carefully migrated to the target core brand. As Antony Burgmans reminded Unilever, “You are not migrating brands, but migrating consumers.” Besides communicating the change to consumers, marketers developed a promotional plan encouraging a trial of the updated brand—an expensive strategy, deployed discriminately.

For example, Unilever positioned Surf, a core-brand laundry detergent with a 6 percent U.K. market share, as “good-hearted, down-to-earth, cuddly, affectionate, and quirky.” Unilever’s U.K. brand portfolio also included Radion, a non-core brand with a 2 percent share slated for elimination. However, research indicated that consumers clung to Radion’s “sun fresh” highly fragrant scent. So Unilever deleted Radion and migrated its scent to Surf by launching a new and improved Surf “with Sun Fresh.” This improved brand exceeded the 8 percent combined share of old Surf and Radion within six months.

Now, three years down its five-year “Path to Growth,” Unilever has met its operating margins and earnings per share growth targets. Although the sales growth is not yet in the 5 to 6 percent target range for 2004, the overall revenue for 2002 increased by 4.2 percent while the core brands grew 5.4 percent. So Unilever is making progress.14

The portfolio has already shrunk to 750 brands. The leading 400 that accounted for 75 percent of sales in 1999 now occupy 200 brand positions and account for 90 percent of sales toward the objective of 95 percent by the end of 2004. Of these, the 40 global core brands alone account for 64 percent of total sales.

Conclusion

With growing retailer power and more global customers, companies cannot sustain weaker brands and must embark on brand rationalization. Since deleting brands usually lowers the firm’s revenues in the immediate short run, brand rationalization is a top management concern. Few divisional, country, or brand managers will risk shrinking the firm. Senior executives must approve the financial objectives of the brand rationalization and the timeframe by which managers should achieve them. This program is geared to deliver long-term benefits, not an immediate earningsper-share increase.

Brand Rationalization Checklist

Brand Portfolio Audit

- Does our brand portfolio hinder us from obtaining adequate scale and scope in our marketing efforts?

- Which brands are contributing to our profits?

- Which brands have scale?

- Which brands are well positioned from consumer and competitive perspectives?

- Which brands have multinational footprints?

- What needs-based segments exist in each category?

- How have we positioned these brands against these needs-based segments?

- Which are our core brands and our non-core brands?

- How much sales revenue would we risk by deleting the non-core brands?

- After brand deletion, will we grow faster, innovate more, and be more profitable?

Brand Rationalization Program

- Which non-core brands could we comfortably sell to others?

- Which non-core brands deprive core brands of valuable shelf space? Should we delist them?

- How can we migrate the customers of delisted brands to core brands?

- Which non-core brands have attributes that would add value to the core brands?

- How can we migrate these attributes to the core brands?

- Which of our non-core brands could we milk for profits?

- How can we move our remaining core brands to better positions against customers and competitors?

- Where can we grow each of our core brands in terms of new customers, geographies, delivery systems, products and services, and concepts?

- Have we explicitly specified financial targets and timelines for the brand rationalization program?

- What is the role for the corporate brand?

Implementation Issues

- In what time frame will we rationalize brands?

- Do we need a quick change or a gradual brand migration?

- Do we have top management’s commitment for that time period?

- Should we adopt a flagship brand or a hierarchical brand approach?

- How will we reallocate resources from non-core brands to core brands?

- How will our product platforms interact with the brands?

- What product roles does each brand need?

- How will we realign local and global responsibilities for the brands?

- Where can we test the viability of our brand rationalization strategy?

- How will we articulate our program and strategy to important stakeholders such as media, analysts, investors, and employees?

Major brand consolidation programs, involving large numbers of brands or multiple categories, may take up to five years. Generally, the profit payoff comes early as unproductive marketing expenditures, inventories, and complexities are rapidly reduced. However, recouping the revenues and market share losses associated with the deleted brands takes time. Top management must be realistic and give managers adequate time to implement the program and demonstrate results (see “Brand Rationalization Checklist”).

Brand rationalization is profitable. It can catalyze broad-based restructuring that ruthlessly removes marketing support for marginal brands, rationalizes the supply chain, purges unprofitable products, and reduces organizational complexity and redundancy.

Imagine a brand portfolio where every brand is smartly positioned with a unique role to play. Only then will disproportionate investments of resources, talent, and innovation in the surviving brands deliver top-line growth.