8

GUIDELINES FOR

IMPLEMENTING AN

HR SCORECARD

DEVELOPING AN HR SCORECARD and actually implementing one are two different things. As our colleague Steve Kerr points out, any change effort has two generic elements defined by this equation:

Effective Change = Quality x Acceptance (or EC = Q x A).

Quality means that the technical aspects of the change have been clearly defined. In the previous chapters, we defined the technical elements of an HR Scorecard. We showed you how the Scorecard must link to your firm’s strategy, be congruent with the company’s HR architecture (HR function, HR systems, and employee behaviors), and pass validity and reliability tests. However a high-quality HR Scorecard is not enough to ensure success. Without acceptance, this change effort might begin with enthusiasm and excitement but will quickly fizzle out.

This chapter explains how to build the acceptance element of your HR Scorecard, that is, how to be disciplined in applying lessons of change management to the implementation of the Balanced Scorecard you develop. It serves less as a road map to what is on the Scorecard and more as a guide to implementing the Scorecard. This chapter gives those charged with implementing an HR Scorecard a blueprint for action.

GENERAL LESSONS OF CHANGE

Most efforts at change fall short of their goals. As Peter Senge and his colleagues report, many of their efforts to create learning organizations did not accomplish the intended results.1 Ron Ashkenas writes that only 25 to 30 percent of change efforts actually succeed.2 James Champy shares similar findings about his work on reengineering, reporting success rates of about 25 to 33 percent.3 Clearly, interventions—no matter how well intentioned and carefully thought out—are far more difficult to put into action than we may think.

Likewise, we have visited many companies that believe that HR measurement matters and that genuinely want to create and use an HR Scorecard. Often these companies express enormous initial interest in this approach, conduct a workshop or two about how to use Scorecards, begin to sort out which HR measures matter most, and track them once or twice. Soon, however, they discover that the commitment to the HR measurement work was more rhetoric and hope than reality and action. In most cases, the “Q,” or technical aspect, of the Scorecard is manageable. (Executives can identify the right measures and create indices to assess them.) But high-quality thinking about the HR Scorecard as a change program never occurs. These companies fail to apply change-management lessons to their implementation of the Scorecard.

Much has been written about how to ensure that desired changes actually happen. In work at General Electric, Steve Kerr, Dave Ulrich, and their colleagues drew on an apt metaphor for effecting successful change. They suggested thinking about change as a pilot’s checklist. Any pilot preparing for a flight rigorously follows a checklist to ensure that the aircraft is ready to fly. This checklist is not meant to be a teaching tool. Indeed, most of us would refuse even to climb into the airplane if we discovered that the checklist was teaching the pilot. In other words, the checklist should contain few surprises. In addition, the pilot should complete each and every action on the list, without fail, every time she or he prepares to go for a flight. Like seasoned pilots, most managers know from both experience and research how to make change happen. The challenge is to figure out how to turn what they know into what they do. At General Electric, Kerr and Ulrich created a “pilot’s checklist” for making change happen and then helped managers develop the equivalent of a pilot’s discipline to apply this checklist to change projects.

Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert Sutton picked up on this theme in their work on avoiding the “smart trap” (this very problem of not knowing how to translate knowledge into effective action).4 To avoid this trap a human resource executive who wants to implement an HR Scorecard should rigorously follow a change checklist. This will increase dramatically the probability that the company will not only design but also use the Scorecard.

Of course, extensive debate has arisen on how to define the critical features of successful change. Douglas Smith identifies ten characteristics of change leaders; John Kotter suggests eight keys to successful leadership of change; Michael Beer’s change model features five core factors.5 But we would argue that using a checklist—any checklist—is more important than choosing one particular checklist over another. Trouble in implementing change comes not from misunderstanding what to do, but from a lack of discipline about how to do what needs doing.

Because we have had experience with the change checklist used at General Electric, let’s use this list to sketch out some guidelines for creating and sustaining an HR Scorecard.6 A team of internal and external change agents designed the GE change checklist.7 They reviewed more than 100 articles and books on individual, team, organizational, and society change and then synthesized the findings into seven key factors. These factors have convergent validity in that they are consistent with the research on other change models; in fact, they are drawn from them. Moreover, these factors have face validity—in other words, managers at GE have confirmed that these factors help make change happen. Finally, the factors also have deployment validity. They have been used in their present or adapted form for thousands of change projects at hundreds of companies. Table 8-1 shows these seven factors and their definitions.8

The seven factors in table 8-1 have been applied in multiple settings and thus offer some general lessons for successful implementation of an HR Scorecard. First, the organization must attend to all seven factors in order for the Scorecard to succeed. The process of initiating and sustaining the Scorecard may be iterative, that is, you may need to cycle back through some of the earlier steps several times. But, in general, the process unfolds in the sequence shown in the table.

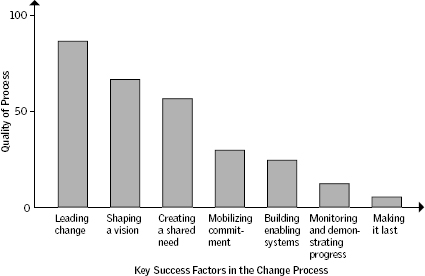

Second, you can use these factors to create a profile of your firm’s present capacity for change on any given project, not just the HR Scorecard. You can generate this profile by scoring the extent to which each of the seven factors exists, using a range of 0 through 100, and plotting those scores as shown in figure 8-1. We recommend that change leaders routinely assess the progress they are making on each of the dimensions of the change process using a simple profiling system such as the one illustrated in figure 8-1. During the planning phase, the profile could be used to inventory the strengths and weaknesses of your company’s current change process. When you consider past change efforts, where has the company been particularly effective and where have those efforts fallen short? This will give you a chance to concentrate on those areas where remediation is required.

Table 8-1 Keys and Processes for Making Change Happen

For example, the experience reflected in figure 8-1 is probably typical of many companies. There is a reasonably enthusiastic cadre of change leaders, but they are only modestly successful at creating a shared sense of urgency around the need for change and communicating a coherent vision of the future if the change is successful. The change leaders understand the need for change and what the future might look like, but they haven’t been effective at articulating that vision to the rest of the organization. Because the foundational elements are not as effective as they should be, the rest of the change process is undermined. It is very difficult to mobilize commitment to change outside the core group because the message for change is not persuasive. As a result, there is little support for changing other institutional levers, such as reward systems, that will reinforce and provide momentum for change. Not surprisingly, there are no early successes to demonstrate progress, and ultimately the change effort never really takes hold and becomes just another “flavor of the month.” Recommendations for successfully accomplishing each of the steps in the profile are summarized in table 8-2.

Figure 8-1 Profiling the Change Process

RATE THE QUALITY OF YOUR CHANGE EFFORT ON EACH DIMENSION.

Third, the change checklist provides a disciplined approach to monitoring the key factors that need more attention. For example, in many HR measurement initiatives, the reason for using the measurement is clear to a broad range of people (that is, the need is already high), but the vision of what the measurement will entail is vague. In these cases, instead of rolling out speeches, conferences, and workshops about the need for the measurement, the organization would be wiser to focus on clarifying and communicating the vision behind the HR Scorecard.

Finally, the change checklist can serve as a powerful new language for talking about how the company might actually implement its HR Scorecard. To illustrate, at General Mills, human resource professionals who work as change agents help their clients through the profiling exercise shown in figure 8-1 on an array of initiatives. In doing so, they familiarize these managers with a new way to think about and discuss change. They can then talk with these clients about how to ensure that good ideas translate into effective, enduring change.

APPLYING CHANGE MANAGEMENT LESSONS

TO THE HR SCORECARD

When a company conceives of its HR Scorecard as an initiative or project, it can apply each of the seven factors to improve the project’s chances. Let’s look at some hints for how to manage each factor.

Table 8-2 Guidelines for Implementing an HR Scorecard

Leading Change

Change is more likely to happen when leaders—in the form of sponsors and champions—support it. A sponsor advocates for the change, sees the value in the change, and commits resources to making the change happen. Often, an HR Scorecard has two sponsors. The primary sponsor is generally the head of HR. This individual calls for an HR Scorecard, assigns a task force to the initiative, ensures that the Scorecard aligns with business strategy, and allocates resources to the task force.

At GTE, executive VP for HR Randy MacDonald actively sought the buy-in of others and held them accountable for performance. He emphasized that the intent of the HR Scorecard was to develop highly effective processes in HR, rather than to identify poor performers. As the change leader, he modeled a commitment to deliver the best possible service to GTE employees, the customers of HR, as well as to increase the value of HR to the bottom line. MacDonald was able to use the HR Scorecard to drive the value proposition of HR within the business. He didn’t just have a seat at the table; he had influence on strategic planning for the business. In this way, senior executive support of the performance measurement initiative was key to the successful rollout of GTE’s HR Scorecard.

The secondary sponsor is often the head of the business or of a division. This person is highly focused on how the company can accomplish its business strategies and understands the important role that the HR architecture plays in strategy implementation. She or he knows that measuring a firm’s HR architecture will improve the firm’s chances of achieving its goals. Moreover, the secondary sponsor is concerned about the wise investment of HR resources. Given the scarcity of resources—in marketing, product design, or employee development—that many organizations face, a wise business leader uses the HR Scorecard to determine how much to invest in the HR architecture. This sponsor encourages the HR Scorecard initiative, uses the information collected to make decisions and public statements about the business, and holds other line managers accountable for delivering on the Scorecard.

The champion for the Scorecard has primary responsibility for making it happen. This person is generally a seasoned human resource professional with accountability for the development of HR. The champion often forms a team or task force to create the Scorecard. Sometimes the champion is responsible for other HR staff areas. For example, at General Mills, the champion is also the head of compensation for the company. And at Prudential, the chief learning officer has taken the lead role in the company’s creation of an HR Scorecard. At GTE, the champion is the director of HR Planning, Measurement, and Analysis. At other times, the champion is charged primarily with “HR for HR,” applying HR lessons to the HR function, and is responsible for governance of HR as well as the Scorecard.

The champion likely dedicates at least 20 percent of his or her time to the creation of the Scorecard. He or she often assembles a team comprising HR professionals from corporate staff and business lines, business leaders, and finance or accounting staff groups. This team builds the business case for HR measurement, crafts the HR scorecard, and oversees its application. The champion requires the strategy performance competencies outlined in chapter 7. He or she reports frequently to the senior HR team about progress on the Scorecard, tracks early adopters to assess successes and failures, and adapts the Scorecard to unique business requirements.

Creating a Shared Need for Change

Change is more likely to happen when a clear reason for it exists. Moreover, the reason for the change has to carry more weight than any resistance to the change. The reason for a change may be related to danger (“we’re in trouble if we don’t change”) or opportunity (“good things will happen if we do change”). Any change effort also offers both short- and long-term impact. It is important to share the reasons for change with those who will be affected.

Creating a shared need for an HR Scorecard requires understanding the importance of HR measures and how these metrics support the business’s strategy implementation. Investing in HR measurement because other companies are doing it or because it is popular will not make the Scorecard sustainable. As we’ve discussed throughout this book, HR measurement must be linked to business results. The HR Scorecard champion should thus be able to articulate the potential outcomes of investment in the initiative. These outcomes might include better allocation of time and money spent on HR, a higher probability of implementing the firm’s overall strategy, more productive and committed employees, a more competitive organization, and increased shareholder value. Sometimes, pointing to the need for an HR Scorecard means asking, “How do we know if we’ve done a good job in HR?” Without a Scorecard, this question often prompts vague answers based on respondents’ personal experience and assumptions about what “good” means. An HR Scorecard gives context and concreteness to these assumptions and personal perceptions, and anchors them in hard data.

Garrett Walker notes that GTE’s motivation to develop an HR Scorecard was primarily driven by accelerating changes in its business environment. Deregulation, the Telecom Act, emerging customer needs, global opportunities, price competition, and multinational reach were creating a new competitive landscape that highlighted a new emphasis on human capital and a new focus for HR. According to Walker,

The senior management team believed that the competitive ability of their workforce was a critical factor in determining their ability to compete effectively. In response to this situation, we developed a Human Capital Strategy that focused on matching employee capabilities with the needs of the business. The key elements of this strategy focused on talent, leadership, workforce development and customer service. We had a good mission statement and vision, an excellent strategy and no quantitative way of measuring how effective we were at executing on the strategy. Simply spending money and being busy were not part of the architecture of success for HR in our current business environment. We needed a way to focus on performance, clarify vision and reinforce business strategy while allowing for learning and change. 9

In clarifying the need to invest in an HR Scorecard, champions should avoid some common pitfalls that will create resistance to it. For example, if the Scorecard measures only part of HR’s effectiveness, it may leave line managers with distorted views of how value is created in the organization. These distorted views can in turn prompt unwise decisions. One company built a Scorecard based primarily on employee productivity and efficiency indices (e.g., revenue/employee, labor costs/revenue, and head-count/margin). Managers in this sales organization thus focused on employee efficiency, not competence. Accordingly, they decided to reduce headcount in order to control labor costs. As it turned out, their lack of attention to the quality of the people on staff ultimately hurt the business. Why? Because more seasoned and expensive employees would have produced more long-term revenue than the kinds of employees who survived the staff reductions. An HR Scorecard champion can avoid this sort of pitfall by using measures with a more effective focus.

Scorecard champions also face potential resistance from HR professionals themselves. As in any other function, some of these individuals don’t want their performance measured. Being in HR without measurement can be a safe, nonthreatening career. With measurement comes accountability, and some of these employees may lack the confidence or competence to be accountable for the work they perform. A Scorecard champion can overcome their resistance through extensive training and investment to ensure that they have the competencies to deliver against higher expectations.

With the trend toward outsourcing many HR functions, measurement of effective HR becomes even more important. The short-term efficiencies that outsourcing may yield might not be sustainable as the longer-term costs—such as single-source suppliers, lack of parity in outsourced HR work, and lack of unique capabilities within the organization—kick in.

For all these reasons, HR Scorecard champions need to build a cogent business case for initiating and implementing the Scorecard. Skillfully crafted, this business rationale will inform line managers, help HR executives make smart choices, and guide and inspire HR professionals throughout the firm.

Shaping a Vision

Change is also more likely to happen when the outcome of the change is clearly understood, articulated, and shared in both aspirational and behavioral terms. Aspirations energize and excite those affected by the proposed initiative’s outcome; definitions of behaviors communicate expected actions. Both become parts of a successful vision statement.

The vision for an HR Scorecard defines the desired outcomes of the Scorecard, states what will be measured, and describes the data-collection process. The desired outcomes are to make informed HR investment choices, identify high- versus low-impact HR practices, document relationships between the HR architecture and business results, and help implement strategy. These outcomes help line managers to accomplish business goals through HR, and human resource executives to govern the elements of the HR architecture.

At GTE, HR professionals responded to the imperatives of the New Economy by articulating a new vision for HR. The HR Scorecard developed by GTE’s HR both communicates and reinforces that vision to all HR managers. Garrett Walker summarized this vision as follows:

We see talent as the emerging single sustainable competitive advantage in the future. To capitalize on this opportunity, HR must evolve from a Business Partner to a critical “asset manager” for human capital within the business. The HR Scorecard is designed to translate Business Strategy directly to HR objectives and actions. We communicate strategic intent while motivating and tracking performance against HR and business goals. This allows each HR employee to be aligned with business strategy and link everyday actions with business outcomes. 10

A well-designed HR Scorecard collects and monitors the information needed to achieve these outcomes. In chapter 3, we reviewed both the administrative and value-creating measures that might make up an HR Scorecard. The HR Scorecard team should begin by identifying the business strategy outlined by the organization. Then, by selecting key items from the choices available in chapter 3, the team may begin constructing the Scorecard. As we’ve seen, the Scorecard generally includes indicators for all three components of the HR architecture: employee behavior, HR system, and HR function. It should be able to pass a simple, but robust test. Simply ask yourself two questions: To what extent does this Scorecard link HR performance to firm performance? Would senior line managers draw the same conclusions?

Mobilizing Commitment

Change is more likely to happen when those affected by the change are committed to it. Commitment comes when these individuals have information about the change process, participate in shaping the process, and behave as if they are committed. Research on commitment suggests that when people behave as if they are committed to an initiative, in a public forum and by choice, they actually become more committed to the initiative.11

HR Scorecards require commitment from both line managers and HR professionals. Line managers’ commitment intensifies when they see the alignment between the HR measures and the achievement of their own business goals. HR processes thus become early leading indicators of successful strategy implementation throughout the rest of the organization. Line managers’ commitment to the HR Scorecard also strengthens when they are held accountable for the measures tracked. An organization in turn can encourage accountability by tying a portion of the manager’s salary and/or bonus to the HR Scorecard. At Sears, employee attitudes, as measured by a commitment survey, accounted for 33 percent of managers’ bonuses. For managers who had the potential to make six-figure bonuses, compensation linked to indicators in the HR architecture captured their attention and changed their behavior. As another example, one restaurant chain began to track average tenure of employees after noticing that front-line worker seniority seemed to correlate with the quality of service that customers received. Managers in this organization were held accountable for their restaurant results and began to hire people who would be more likely to stay. These managers also focused on building more positive relationships with employees and sharpening their retention strategies.

At times, merely making HR Scorecard data public builds commitment from line managers. One consumer-products firm was having trouble keeping future brand managers. The leadership team decided that each of the fifteen members of the executive committee would become sponsors of five newly hired potential brand managers per year for five years. Over time, each of the fifteen senior executives had twenty-five relatively new employees whom they mentored. This strategy entailed meeting regularly with the employees, providing them with career advice and counsel, and paying attention to them. Although the mentoring program was not incorporated into the fifteen executives’ formal performance reviews, the managers provided annual reports on how many of their twenty-five charges left the firm each year. This informal pressure prompted each of the fifteen executives to reach out especially to those employees who would most likely leave the firm. These executives made a solid commitment to the HR Scorecard simply because its importance and visibility were crystal clear.

HR managers also must be committed to the Scorecard. If the items that it tracks are not central to the performance management of the HR professional, there is a problem with either the Scorecard or the performance management process. We tested this assumption with the head of HR in a high-tech firm. We asked her, “When your CEO engages you in serious conversation, what issues is he most worried about?” She responded that the CEO wanted her to help attract thought leaders in the business, build the next generation of leadership for the firm, and hold leaders accountable for results. We then asked her to show us her HR Scorecard and personal performance metrics. They matched the three strategies that she had cited. Clearly, she was personally accountable for what the CEO wanted from her HR function. The alignment of the CEO’s expectations, the HR Scorecard for her function, and her personal objectives ensured that her actions reflected and supported the firm’s goals.

The commitment to the HR Scorecard accelerated at GTE as HR managers learned more about the business strategy, how it translated into HR strategy, and how it ultimately linked to business outcomes. Using strategy maps and leading and lagging indicators, they were able to help employees “connect the dots” and think across the organization and the business. By communicating business value chains where HR actions are simply part of the transformation process, HR managers were able to understand more than their functional silos. They could see the big picture.

In spite of this attention to change management issues, some resistance is inevitable. Garrett Walker notes the following:

Much of the early resistance from HR came from the release of information. Information is power and losing that power coupled with the possibility of “looking bad” was a real obstacle early on. However, each quarter that the Scorecard was in place more information was available. The Scorecard exposed HR managers as well as business leaders to workforce issues outside of their expertise and illustrated linkages to other parts of the business. Now, HR professionals and line managers discuss organizational and workforce issues outside their immediate responsibility. The HR Scorecard has created a distinction, a common language, for communicating critical human capital issues.

We rolled the entire HR Scorecard out at once; however, we communicated and published information in a phased approach. We began with senior HR leaders and business leaders, introducing them to the concepts and measurement model. The senior HR leaders then communicated to their organizations. To supplement high level staff briefings the HR Scorecard team provided on-site briefings to departments focusing on linkages between the departmental actions and business outcomes (cause and effect mappings). We also had “lunch and learn sessions” where informal Q&A from the HR Scorecard team was supplemented with success stories from HR practitioners who had used the Scorecard to positively impact the business.

The Scorecard was also immediately tied to incentive compensation at all levels of the HR organization. This was somewhat controversial at the time, but certainly kept the organization’s eye on the ball. In hindsight, this action eliminated much of the resistance to the Scorecard. 12

Commitment from both line managers and HR professionals increases when a firm frequently tracks the indicators on the HR Scorecard and shares the information openly. For instance, a bank created an HR report card to measure the firm’s success at increasing its share of targeted customers. By sharing the report quarterly among all HR professionals and senior line managers, the firm ensured that the Scorecard influenced behavior.

Building Enabling Systems

Change is more likely to happen when a company makes the financial, technological, and HR investments required to support the change. The experience at Intel offers an apt example of financial support for the HR Scorecard. Patty Murray, the vice president of HR, invests in ongoing research to identify the key HR drivers of business success. She has an R&D function that is charged with identifying which HR practices are most critical to Intel’s future success. For example, as Intel moved into the Internet business, Murray’s R&D team identified the talents required for the firm to make this business transition. The team not only built a talent-acquisition strategy, but also designed measures for monitoring this strategy.

HR Scorecards also require technological investments to support the collection, tracking, and use of data. Cisco, for example, gathers employee attitude data through its intranet Web site. Organizations can also collect such data from a subset of employees monthly or quarterly and then quickly codify it to inform managers about employee commitment in subunits throughout the firm. Use of data-collection and analysis technology ensures that the Scorecard remains timely and accurate.

Building enabling systems also means that the results of the Scorecard need to be communicated widely throughout the business. GTE has developed a wide range of integrated tools to communicate its HR Scorecard and to help managers make good decisions using the data. At the heart of this system is an intranet linked to a data warehouse. Previously, GTE had seventy-five different information systems, which were combined into a single system at the outset of this process. This system now places timely and relevant data on managers’ desktops, which they can access using special software that enables them to set goals and track performance. GTE has also developed an interactive CD-ROM simulation that shows managers how to use the system to improve their decision making. Finally, GTE has prepared a wide range of reports and background material (available in hard copy or on the intranet) that employees can access at any time.

In the GTE HR Balanced Scorecard environment, there are different measures for major functions, such as staffing for each business unit, which are accessible via Internet technology. This makes the Balanced Scorecard a highly effective system for communicating strategic goals. HR leaders can view a virtual briefing book on their desktop computers that displays the performance results for the key peformance indicators they are most interested in. If they have a question about a measure or result, they can drill down by clicking on it to reveal more and more detail. Much of the detail comes from individual employees, who enter data and notes about what’s happening on the front lines into an HR Scorecard system. These desktop briefing books also tell them how their performance matches their goals. According to Garrett Walker,

The HR Balanced Scorecard helps our HR professionals react more quickly as a whole, from the executive suites to the front lines. Even more important in a business environment of rapidly changing markets and accelerating technology advances, it helps management teams anticipate workforce issues so they can plan rather than react. In our previous business environment we often had weeks to make decisions. The HR Balanced Scorecard system allows us to rapidly adjust to changes affecting our business in real time. 13

In essence, GTE uses its Scorecard as a teaching tool and as a key mechanism for helping to implement its strategy. And the level of resources and visibility devoted to the project help to demonstrate the firm’s commitment to the measurement project. The end result of these efforts is a much more effective HR measurement system and considerable visibility for the project—both inside and outside of the firm. At GTE, the Scorecard has helped to build internal and external credibility for both the HR function and the firm as a whole.

The HR Scorecard has also proved of considerable benefit in facilitating GTE and Bell Atlantic’s recent merger into Verizon. The HR Balanced Scorecard is an evolving and highly valuable tool for both the HR management team as well as the business leaders. Its key value in merger integration was to pull together the formerly separate management teams of Bell Atlantic and GTE. GTE human resources relied on a centralized model, which delivered HR products and services by a strong central staff. Bell Atlantic, on the other hand, relied on a more decentralized approach. The differences in style and approach naturally gave rise to tug of wars after the merger.

In the early days following the merger, the HR Balanced Scorecard provided a process for the Verizon human resource leadership team (HRLT) to focus on common objectives and the future of the new business. The primary focus of the HR Balanced Scorecard forums was to translate business strategy into HR strategy and actions. The process allowed the HRLT to overcome their differences in management style and come together as a team. A shared sense of HR strategy and focus emerged from the early meetings. The Verizon HR Balanced Scorecard emphasizes a core common focus on the customer, especially the need to improve service, to attract and retain talent, and to increase value created for the business.

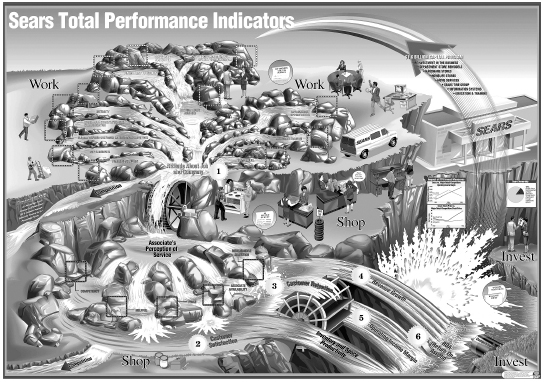

Building enabling systems also means helping to communicate the firm’s strategy map and resulting HR Scorecard to the workforce. Like many firms, Sears found that many employees did not completely understand the company’s strategy, business environment, or even key business processes. Sears responded by communicating its strategy to the workforce via “town hall” meetings and Learning Maps.14 Learning Maps are large (forty-inch-by-sixty-inch) image-laden depictions of a firm’s strategy or other key business processes. The figure in the center of the map is surrounded by a series of questions and learning objectives, on which employees work together in small groups in order to increase their understanding. Employees then go back into their work groups and repeat the process with a new group of employees. The authors of the Sears study describe the process as follows:

The goal of learning maps is economic and business literacy—but business literacy in the service of the larger goal of behavioral change. We want managers to change their behavior toward employees, to communicate the company’s goals and vision more effectively, and to learn to make better customer-oriented decisions, because we cannot do well financially unless we do well in the eyes of the customer. We want frontline employees to change their behavior toward customers—to become more responsive, take more initiative, and provide better service. 15

Sears has developed several Learning Maps to date, with more on the way. The company has found them to be a highly effective way to communicate with the workforce. Sears’s most recent map, “Ownership,” describes their total performance indicators (TPIs) and shows employees how measurement can help them to create value. Using the metaphor of water running downstream, the “Ownership” map shows not only the key business processes around Work, Shop, and Invest, but also how the TPI metrics map on to these processes (see figure 8-2).

Finally, HR Scorecards require investments in human resource systems. Hiring HR employees with the competencies we suggested in chapter 7, communicating the Scorecard throughout the organization, and weaving HR results into reward and recognition systems all help to sustain the Scorecard. Such systems should ensure that HR measures change behavior in the right ways. For example, an HR Scorecard could collect data on the cost of turnover and thus show the importance of retention. But if these data are not used as part of a manager’s performance review (in which questions such as, “What is the turnover rate of key people in your unit?” are asked), then the data is unlikely to change behavior. Or, if the data is collected but managers who have high turnover are consistently promoted to new positions, the HR Scorecard will lose credibility and impact. At Sears, fully one-third of a manager’s bonus is linked to his or her ability to manage people. Prudential ties 20 percent of managerial compensation to its HR Scorecard. Many other firms are beginning to use the leading indicators embedded in their HR Scorecards as a component of managerial compensation.

Figure 8-2 Sears Total Performance Indicators

Source: Reprinted with permission of Sears and Root Learning, Inc.

Monitoring and Demonstrating Progress

Change is more likely to happen when a firm monitors progress toward the change. We thus recommend creating—and sticking to—a plan for implementing your HR Scorecard. Dividing the plan into milestones can help; for example:

• Naming the champion. This will be the person who will lead the effort, invest time and energy in it, and ultimately be held accountable for success.

• Creating the Scorecard team. The team will likely include HR professionals from both corporate and field, line managers who bring the business perspective, financial and/or strategy staff who ensure that the measures are consistent with corporate goals, and possibly external experts who draw on experiences from other companies.

• Selecting targeted measures. Based on the process described in chapter 3, the Scorecard team may choose appropriate measures for all elements of the HR architecture. These measures should be keyed to the firm’s strategy implementation plan and reflect informed investment in HR practices.

• Validating the measures. Hypothesizing the right measures and testing their impact on business results require different skills. You can do some hypothesis testing retrospectively if historical measures of your firm’s HR architecture and business results exist. For example, Sears’s work showed relationships among employee commitment, customer loyalty, and firm performance, with twenty years of historical data collected at each store. This reservoir of data let managers test valid measures. Other validation may come from pilot tests, whereby you can collect data from limited sites to ensure that the selected measures will support desired business results.

• Collecting data. Once you validate your measures, you can collect the HR data you need to track key items. These data may come from employee surveys, existing corporate reports, or reports generated to track key indicators.

• Monitoring and updating data. As you collect data, you can track trends to create a longitudinal HR Scorecard that will highlight patterns and trends over time. With valid data, you can then assess the impact of HR and make decisions about which HR investments will help improve the firm’s business results.

Data need to be updated in accordance with their level of actual variability. Relatively stable data can be updated annually—more variable (or urgent) attributes should be updated quarterly, monthly, or even weekly, as appropriate.

Monitoring your progress at each stage of creating and using the HR Scorecard ensures that the project unfolds as planned. Periodically revisiting the Scorecard itself also helps you assess how well it is helping you improve HR investment decisions and how well it is supporting the organization’s strategy implementation efforts.

Making It Last

Change is more likely to happen when a change effort garners early success, builds in continuous learning about what is working and what is not, adapts to changing conditions, celebrates progress, and can be integrated with other work. To do all of this, you must make ongoing investments in your HR Scorecard. Here are some hints for making the scorecard last:

ENSURE EARLY SUCCESSES

Many companies face a dilemma: Should they invest in developing a complete, fully researched, and comprehensive HR Scorecard that takes months to develop? Or should they limit the effort to just those measures that let them evaluate critical capabilities right away, based on available data? We suggest choosing the option that lets you rack up some early successes, even if they’re relatively small in scope. For some firms, this might mean running simultaneous experiments to identify which HR data exert the most impact on business results. It might also mean experimenting with various tracking methods (e.g., should you measure employee commitment by a pulse check, retention, or productivity?) and seeing which method best predicts business results. Having internal case studies that specifically demonstrate which HR data influence business success builds credibility for the entire Scorecard process.

MAINTAIN INVESTMENT IN THE SCORECARD

Once they establish the HR Scorecard, the initiative team should remain intact. As the company continues to use the Scorecard, these team members will need to continue to update and modify it. In addition, the firm should make regular investments, in the form of data collection, people, and money in order to ensure that the Scorecard remains robust, up to date, and relevant.

INTEGRATE THE SCORECARD WITH OTHER WORK

The Balanced Scorecard works because it measures all the dimensions relevant to a firm’s success. Likewise, the HR Scorecard should be integrated with other measures of managerial success. To illustrate, a meeting in which participants examine the links among HR, customer, investor, and business process measures is far more valuable than one in which attendees focus only on HR measures. The more a company can integrate its HR Scorecard with existing and ongoing measurement efforts, the more sustainable the Scorecard will be.

LEARN FROM EXPERIENCE

With any change effort, you need to conduct periodic check-ups to examine what is and what is not working. Likewise, make a commitment to examine your HR Scorecard effort every six or twelve months. During these assessments, the Scorecard team should answer questions such as the following:

• What has worked in the HR Scorecard initiative to date?

• What hasn’t worked? What explains any lack of success? Were data not available, not collected, not tied to results, not monitored, not part of existing management practices?

• What can we do differently, based on our experiences so far with this initiative?

As you address these questions on a regular basis, the HR Scorecard will become increasingly ingrained in the management process.

SUMMARY: DOING IT

HR Scorecards are not panaceas. They will not cure a poorly run HR function. However, they do provide a means by which you can collect rigorous, predictable, and regular data that will help direct your firm’s attention to the most important elements of the HR architecture. Constructed thoughtfully, the HR Scorecard will help your organization deliver increased value to its employees, customers, and investors. By applying the seven steps we suggest in this chapter, you can integrate the thinking behind the HR Scorecard into every key aspect of your firm’s management.

Our book has laid out the theory and tools for crafting an HR Scorecard. Using these ideas and tools will help HR professionals become full partners in their firms. While much of the work of an HR Scorecard is technical, the delivery of the Scorecard is personal. It requires that HR professionals desire to make a difference, align their work to business strategy, apply the science of research to the art of HR, and commit to learning from constant experimentation. When you create the HR Scorecard, using the approach we describe, you are actually linking HR to firm performance. But you will also develop a new perspective on your HR function, practices, and professional development. In measurement terms, the benefits will far outweigh the costs.