3

CREATING AN

HR SCORECARD

AS WE’VE SEEN, an HR Scorecard lets you do two important things: (1) manage HR as a strategic asset and (2) demonstrate HR’s contribution to your firm’s financial success. Although each firm will depict its Scorecard in its own way, a well-thought-out Scorecard should get you thinking about four major themes: the key human resource deliverables that will leverage HR’s role in your firm’s overall strategy, the High-Performance Work System, the extent to which that system is aligned with firm strategy, and the efficiency with which those deliverables are generated.

We discuss these dimensions of the HR Scorecard in more detail later in this chapter. However, to begin to understand what building an HR Scorecard requires, let’s look at that process in a company we’ll call HiTech. For the sake of illustration, we’ll focus on HiTech’s R&D function and explore HR’s potential role in this unit’s strategy implementation model. As in many business units, R&D at HiTech has profitability goals that hinge on both revenue growth and productivity improvement—two important performance drivers. To build an HR Scorecard for just this unit, we need to understand the role that HR plays in these two dimensions of the R&D strategy map. We could describe this role as follows:

• Revenue growth ultimately derives from increased customer satisfaction, which in turn is boosted by product innovation and reliable delivery schedules, among other things.

• Product innovation strongly depends on the presence of talented staff with significant company experience. Through competency-based selection methods and retention programs, HR contributes to stable, high-talent staffing in R&D.

• Reliable delivery schedules in part hinge on the maintenance of optimal staffing levels in manufacturing. Even if turnover in manufacturing is low, the company must fill vacancies quickly. By reducing recruiting cycle time, HR supports optimal staffing levels.

• Productivity improvement has links to the maintenance of optimal production schedules, which in turn depends on the maintenance of appropriate staffing levels. Again, HR recruiting cycle time drives staffing levels.

DEVELOPING AN HR MEASUREMENT SYSTEM

Now let’s “walk through” a few steps in the HR Scorecard approach in order to illustrate how HiTech might begin developing its human resource measurement system.

Identifying HR Deliverables

There are two HR deliverables in this example. The first is stable, high-talent staffing in the R&D function. This deliverable has several dimensions. For one thing, the R&D staff must have the unique competencies defined by HiTech and must demonstrate those competencies at the highest levels. These competencies combine cutting-edge technical knowledge with the specialized product demands found in HiTech. Thus they are not influenced by in-house professional-development efforts. Moreover, because these competencies are specific to HiTech and require several years of firm experience to develop, the company must keep its R&D staffing turnover very low.

The second HR deliverable is optimal staffing levels in the manufacturing unit.

Both of these deliverables have clear implications for HiTech’s overall performance. One contributes to revenue growth, while the other influences productivity growth.

High-Performance Work System

Once the HR deliverables have been clearly defined, we can begin to identify and measure the foundational High-Performance Work System elements that help to generate those deliverables. We term these elements a High-Performance Work System to represent the fact that they have been selected specifically with the intent of implementing strategy through the HR deliverables. In the case of HiTech, this means designing and implementing a validated competency model linked to every element in the HR system, and providing regular performance appraisals to all employees. As with all of the other elements of the HR scorecard, there are a variety of ways that these data can be represented. The most common approach is to present the proportion of achievement on each element, although it is also possible to indicate whether or not each element is either up to standard or below standard with a toggle indicating red (below standard), yellow (marginal), or green (meets standard).

Identifying HR System Alignment

What HR system elements need to reinforce one another so as to produce the two HR deliverables? In the case of stable, high-talent staffing in R&D, we can assume that the firm has developed a validated competency model. At HiTech, selection into these positions must correspond to the existing competency model, and the quality of the hires should be at the highest levels. These alignment goals would strongly influence the particular sourcing decisions needed to produce those results. However, the sourcing decisions do not have to be part of the HR Scorecard. The assumption is that since you are measuring the outcomes of those sourcing decisions and since “what gets measured gets managed,” then sourcing decisions will be guided by the need to achieve these outcome goals.

HiTech also needs to enact the kinds of retention policies that build experience in the R&D unit. Note, though, that understanding that retention policies are a key leading indicator is more important than the actual selection of policies, which are unique to each firm. At HiTech, a carefully chosen range of HR activities and policies, from supervisory training to unique benefit packages, might be in order. The key thing is that seemingly irrelevant HR “doables” have a clear strategic rationale.

To achieve optimal staffing in manufacturing, HR must keep its recruiting cycle time short. The appropriate alignment measure—for example, a fourteen-day recruiting cycle time—would reflect progress toward that objective.

Identifying HR Efficiency Measures

In this simple example, HiTech could identify cost per hire as a strategic efficiency measure. For both deliverables, cost per hire will probably be higher than average. But, the benefits of those hiring processes will also be well above average. The HR Scorecard that HiTech develops should highlight these links between important costs and benefits.

Figure 3-1 gives you a basic idea of how HiTech’s R&D HR Scorecard might look. Of course, an HR Scorecard for the entire company would include many more entries. This diagram represents a concise but comprehensive measurement system that will both guide HR strategic decision making and assess HR’s contribution to R&D’s performance. More important, the scorecard is presented in such a way that it reinforces the “causal logic” or strategy map of how HR creates value at HiTech.

THE THINKING BEHIND THE HR SCORECARD

Why have we chosen the identification of HR deliverables, the use of the High-Performance Work System, HR system alignment, and HR efficiency measure as essential elements of the HR Scorecard? We believe that this arrangement reflects a balance between the twin HR imperatives of cost control and value creation. Cost control comes through measuring HR efficiency. Value creation comes through measuring HR deliverables, external HR system alignment, and the High-Performance Work System. These last three essential elements of the HR architecture trace a value chain from function to systems to employee behaviors.

In the following two sections, we outline a way of thinking about cost control and value creation. Again, it is more important that managers understand the reasoning behind the Scorecard than narrowly follow the particular format we have selected. The value of the Scorecard diagram itself lies in the thinking that goes into it and its power as a decision-making tool once it’s constructed.

The Bottom-Line Emphasis:

Balancing Cost Control and Value Creation

Like most HR managers, you are probably under constant pressure to help your organization “drive out costs.” Indeed, many line managers consider much of what HR does as overhead. In many instances, these managers are correct, which puts even more responsibility on HR to find efficiencies wherever possible. We acknowledge these demands and believe that every HR Scorecard should include a dimension that captures the efficiency of the HR function. The problem is that, in organizations that view HR as nothing more than a cost center, efficiency of the HR function tends to be the only bottom-line metric in the HR measurement system.

Yet despite this imperative to measure HR efficiency, the HR function does not have a strategic significance for the organization. HR efficiency has the same value as any other accounting-focused form of cost control, but it doesn’t generate unique, intangible assets over the long run. Recall our analysis in chapter 1 of how the structure and alignment of the HR system contribute to shareholder value. We made no mention of HR efficiency in that discussion, because it is not typically a source of value creation. And in chapter 2, where we discuss the research behind making the business case for strategic management of HR, we did not mention efficiency.

Figure 3-1 HR Scorecard for HiTech’s R&D Function

Why have we put so little emphasis on this theme? First, efficiency in the HR function simply can’t generate enough cost savings to substantially affect shareholder value. Second, whatever competitive advantage such efficiencies might offer is very likely lost as other firms adopt such practices. In other words, most HR functions are fairly adept at providing efficient HR processes; this capability doesn’t distinguish the successful from the unsuccessful firm. Therefore, these sorts of measures will play a limited role in determining HR’s strategic influence.

There’s a crucial difference, however, between cost control and efficiency within the HR function and HR’s contribution to cost saving and efficiency in line operations. For example, most balanced performance measurement systems contain metrics assessing both revenue growth and productivity or efficiency. “Efficiency” will often be represented by a financial lagging indicator, such as “reduce unit costs.” A number of performance drivers will map onto that indicator (the arrows in your strategy map), but many won’t. When HR enablers affect the “efficiency” component of those drivers, they are actually influencing the efficiency of line operations. In the HiTech example, there is a clear line of sight between efficient HR recruiting processes and the firm’s bottom line through HR’s contribution to improved operating efficiency. This point was also illustrated by our example in chapter 2 of GTE’s traditional narrow focus on HR efficiency. Their efforts to reduce hiring cycle as an efficiency measure ultimately resulted in business problems that were much more significant than the original efficiency gains.

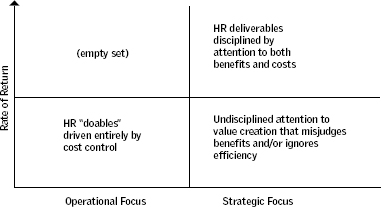

Still, the HR Scorecard needs to emphasize HR’s value creation, tempered by attention to efficiency. Only in this way can the human resource management system strengthen HR’s strategic influence in the organization overall. That is why most of the Scorecard should focus on the value created through HR’s contribution to strategy implementation. Figure 3-2 illustrates this perspective.

As this figure suggests, if HR managers are measuring what matters, they are measuring those HR decisions and outcomes that get the highest rate of return. For example, the operational side (the traditional focus of HR) focuses largely on doables (HR efficiency) and generates a limited rate of return. Though exceptions exist, we consider the operational-high-return outcome an “empty set.” There are so few high-return opportunities on this side of HR that they probably are not worth exploring at length here. At the same time, blindly focusing on “strategy” doesn’t guarantee high returns either. In fact, this “tunnel vision” led to much of the frustration in the early years of “strategic” HR. During that time, human resource managers devoted too much effort to getting a seat at the strategic planning table and overlooked the greater opportunities available in strategy execution. They weren’t developing a strategically focused HR architecture that is the key to HR’s value as a strategic asset. These HR managers were operating in that lower-right-hand corner, exchanging one low-return philosophy for another.

Balancing cost control and value creation measures helps HR managers to avoid another mistake as well: the tendency to focus on the benefits of HR’s strategic efforts while ignoring the costs of those benefits. The highest rates of return for HR come from a disciplined strategic focus. HR deliverables, rather than doables, are the source of these benefits, but only if the HR system is managed efficiently. Remember doables tend to be cost-focused; deliverables, benefits-focused. In practice, many HR processes that comprise the doables are the costs associated with generating the deliverables. It’s not that doables are unimportant; it’s just that you need to gauge how well they translate into deliverables with value. You must keep both in mind when evaluating HR’s overall rate of return.

Figure 3-2 Balancing Cost Control and Value Creation

Let’s revisit the HiTech example to see how this works. In that scenario, HR’s ability to reduce recruiting cycle time improved operational efficiency in the R&D unit and would ultimately boost financial performance for the entire firm. But reducing recruiting cycle time from, say, fifty-two to fourteen days might well have required special investment in staff or technology. Managers focused only on efficiency may have recoiled at the additional cost and rejected the decision to invest. Even HR managers who understood that this was the right decision may have had only a vague sense of whether the benefits would truly justify the cost. An appropriate measurement system would have shown them in concrete terms that the decision to invest in reduced recruiting cycle time could pay off.

This example illustrates another advantage of understanding the balance between cost control and value creation. Many HR managers work for firms that pride themselves on being “lean and mean.” Such organizations keep HR thinly staffed, so as to control overhead as much as possible. This policy can be shortsighted if HR is truly to serve as an intangible asset. As we saw in chapter 1, high-performing firms had more than twice as many HR professionals per employee as did low-performing firms. Even more frustrating, many organizations now expect HR managers to play a strategic role—but with no increase in resources. Under these circumstances, most managers are almost doomed to fail. The only way they can pass this test is to demonstrate, through their measurement system, how resources allocated to HR might actually create value.

The Architectural Emphasis:

Which HR Value Chain Elements Go into the Scorecard?

Since the primary focus of HR’s strategic role is value creation, thinking about HR architecture means taking the broad view of HR’s value chain. Just as a corporate scorecard contains both leading and lagging indicators, the HR Scorecard must do the same. Of the four HR architecture elements that we recommend including in the Scorecard—High-Performance Work System, HR system alignment, HR efficiency, and HR deliverables—the first two are leading indicators and the second two are lagging indicators for HR’s performance.

Measuring the High-Performance Work System lays the foundation for building HR into a strategic asset. A High-Performance Work System maximizes the performance of the firm’s employees. The problem is that the performance dimension tends to get lost in the attention most firms give to issues of efficiency, compliance constraints, employee relations, etc.—none of which is part of HR’s strategic role. This is a mistake. The performance dimension needs to have prominence if a firm wants to enjoy the financial benefits that the Scorecard approach makes possible. Therefore, every firm’s HR measurement system should include a collection of indicators that reflects the “performance focus” of each element in the HR system.

As we’ve seen, measuring HR system alignment means assessing how well the HR system meets the requirements of the firm’s strategy implementation system, or what we have called “external” alignment. We have also mentioned “internal” alignment, defined as the extent to which each of the elements worked together rather than in conflict with one another. We do not give equal emphasis to internal alignment in our measurement system because, if the HR system is uniformly focused on strategy implementation, the elements should tend toward internal alignment. In other words, if HR managers can manage external alignment, then internal misalignments will tend to disappear. A focus on internal alignment becomes more appropriate as an initial diagnostic for those firms that have not adopted a strategic HR perspective. Internal misalignment, therefore, is much more likely to be a symptom of an operationally focused HR system.

HR efficiency reflects the extent to which the HR function can help the rest of the firm to generate the needed competencies in a cost-effective manner. This does not mean that HR should try to simply minimize costs without attention to outcomes, but neither should they “throw money off the balcony.” The metrics included in this category should reflect that balance.

And finally, HR deliverables are the key human-capital contributors to implementation of the firm’s strategy. They tend to be strategically focused employee behaviors, such as the low turnover rates in the HiTech example.

How does this simple illustration in figure 3-3 help us in understanding the appropriate structure of an HR Scorecard? While we will develop these ideas in more detail later in the chapter, there are some organizing principles to keep in mind. The structure of a strategic HR measurement system depends on striking the correct balance between efficiency and value creation, while being guided by a broad strategic rather than a narrow operational perspective on HR.

It is important to understand that proper positioning on both dimensions (see figure 3-3) provides the basis for synergies between HR management and the measurement system. In other words, for HR to be able to demonstrate a significant impact on firm performance, the HR architecture must be designed as a strategic asset and the HR measurement system must be designed to guide the management of that strategic asset.

CONSTRUCTING THE HR SCORECARD

Now that we’ve talked about the four dimensions—HR deliverables, the High-Performance Work System, external HR system alignment, and HR efficiency—that should go into the HR Scorecard and the reasoning behind including them, let’s move on to how you might actually use them to construct your Scorecard. First, we will take a closer look at each dimension.

The High-Performance Work System

HR’s strategic influence rests on a foundation of high-performing HR policies, processes, and practices. However, given the conflicting demands that HR managers typically confront, these professionals need a set of measures that keep the performance dimension of those HR activities at the forefront of their attention. Such measures don’t reflect what is as much as they remind managers of what should be. Therefore, they can be represented on the HR Scorecard as simple toggles, indicating “unsatisfactory” or “satisfactory.” Or, they can be included as metrics along a continuum.

Figure 3-3 The Synergy of Measurement Structure

For an illustration of the kinds of broad questions we include in our HPWS survey, see the sidebar “Examples of High-Performance Work System Measures.” As you can see, these questions are not designed to test whether an organization is current on the very latest HR fad or has added another ten degrees to its performance-appraisal system. Rather, they work through each HR function from a “macro” level and highlight the performance orientation of each activity.

EXAMPLES OF HIGH-PERFORMANCE WORK SYSTEM MEASURES

• How many exceptional candidates do we recruit for each strategic job opening?

• What proportion of all new hires have been selected based primarily on validated selection methods?

• To what extent has your firm adopted a professionally developed and validated competency model as the basis for hiring, developing, managing, and rewarding employees?

• How many hours of training does a new employee receive each year?

• What percentage of the workforce is regularly assessed via a formal performance appraisal?

• What proportion of the workforce receives formal feedback on job performance from multiple sources?

• What proportion of merit pay is determined by a formal performance appraisal?

• If the market rate for total compensation would be the fiftieth percentile, what is your firm’s current percentile ranking on total compensation?

• What percentage of your exempt and nonexempt employees is eligible for annual cash or deferred incentive plans, or for profit sharing?

• What percentage of the total compensation for your exempt and nonexempt employees is represented by variable pay?

• What is the likely differential in merit pay awards between high-performing and low-performing employees?

Jeffrey Pfeffer has developed a similar set of high-performance characteristics that he associates with a firm’s ability to transform people into a source of competitive advantage.1 He includes selective hiring, high pay, incentive pay, employee ownership, information sharing, and an emphasis on training and development. But in addition, he cites several dimensions designed to provide more employee equity in organizational processes and outcomes. Among the latter, he mentions employee participation and empowerment, narrower pay differentials across the firm, symbolic egalitarianism, and greater employment security. For your reference, we’ve listed more High-Performance Work System metrics in table 3-1.

HR System Alignment

The next component in the HR Scorecard encourages you to gauge the alignment of the HR system with drivers of the firm’s strategy implementation process. To transform a generic High-Performance Work System into a strategic asset, you need to focus that system directly on the human-capital aspects of those drivers.

Choosing the correct alignment measures is relatively straightforward, if you begin with the process discussed in chapter 2. This process helps you understand the exact HR deliverables required to create value in the organization, which in turn indicates specific elements of the HR system (leading indicators) that must reinforce one another in order to produce those deliverables. Therefore, specific alignment measures will be linked directly to specific deliverables in the Scorecard. Connecting them in this way highlights the cause-and-effect relationships needed to support HR’s contribution to firm performance.

Table 3-1 High-Performance Work System Measures

| Average merit increase granted by job classification and job performance | Percentage of employees whose pay is performance-contingent |

| Backup talent ratio | Percentage of employees with development plans |

| Competency development expense per employee | Percentage of total salary at risk |

| Firm salary/competitor salary ratio | Quality of employee feedback systems |

| Incentive compensation differential (low versus high performers) | Range (distribution) of performance-appraisal ratings |

| Number and quality of cross-functional teams | Range in merit increase granted by classification |

| Number and type of “special projects” to develop high-potential employees | |

| Number of suggestions generated and/or implemented |

To select the appropriate alignment measures, focus on those elements of your HR system that make a definable and significant contribution to a particular HR deliverable. These differ for each firm, but the experience at Sears described in chapter 1 is a good example. Identifying these measures requires you to combine a professional understanding of HR with a thorough knowledge of the value-creation process in your own firm. Remember that the alignment measures will follow directly from the “top-down” process. Based on the larger “strategy map” (Step 3 in our seven-step model), you will identify your HR deliverables, which in turn will point to certain elements of the HR system that require alignment. Therefore, there are no standard alignment measures that can be provided as examples. Instead, we emphasize the need for a standard process by which each firm will develops its own set of alignment measures.

Much like the High-Performance Work System measures, the external HR system alignment measures are designed largely for use within a firm’s HR department. They too can be represented as toggles on the Scorecard, indicating alignment or nonalignment. The key issue is that they prompt HR managers to routinely think about alignment issues and highlight areas requiring action.

HR Efficiency: Core versus Strategic Metrics

As an HR professional, you doubtless have access to a wide range of benchmarks and cost standards by which you can measure HR’s efficiency. We show a number of these in table 3-2.2 All of these metrics encourage cost savings and are the kinds of measures you would find in the first level of our measurement pyramid (figure 2-9 in chapter 2). But unless you want HR to be treated like a commodity in your organization, you should beware of building your measurement system unthinkingly on these generic benchmarks. Instead, separate out the costs associated with HR commodities such as employee benefits transactions and policy compliance, and the unique investments required to create HR’s strategic value in your organization. (These choices will differ for each organization. Part of our rationale for including such a long list of potential metrics is to highlight the importance of choosing key metrics carefully using the process we have described. Otherwise, it is possible to become overwhelmed by the potential choices). Benchmarking is fine for the HR commodity activities, but it has no significant influence on your firm’s ability to implement its strategy.

Table 3-2 HR Efficiency Measures (Doables)

| Absenteeism rate by job category and job performance |

| Accident costs |

| Accident safety ratings |

| Average employee tenure (by performance level) |

| Average time for dispute resolution |

| Benefits costs as a percentage of payroll or revenue |

| Benefits costs/competitors’ benefits costs ratio |

| Compliance with federal and state fair employment practices |

| Compliance with technical requirements of affirmative action |

| Comprehensiveness of safety monitoring |

| Cost of HR-related litigation |

| Cost of injuries |

| Cost per grievance |

| Cost per hire |

| Cost per trainee hour |

| HR department budget as a percentage of sales |

| HR expense per employee |

| HR expense/total expense |

| Incidence of injuries |

| Interviews-per-offer ratio (selection ratio) |

| Lost time due to accidents |

| Measures of cycle time for key HR processes |

| Number of applicants per recruiting source (by quality) |

| Number of hires per recruiting source (by quality) |

| Number of courses taught by subject |

| Number of recruiting advertising programs in place |

| Number of safety training and awareness activities |

| Number of stress-related illnesses |

| Number of training days and programs per year Offer-to-acceptance ratio |

| OSHA audits |

| Percentage of and number of employees involved in training |

| Percentage of correct data in HR information system |

| Percentage of employee development plans completed |

| Percentage of employees with access to appropriate training and development opportunities |

| Percentage of new material in training programs each year |

| Percentage of payroll spent on training |

| Percentage of performance appraisals completed on time |

| Response time per information request |

| Sick days per full-time equivalent per year |

| Speed of salary action processing |

| Time needed to orient new employees |

| Time to fill an open position |

| Total compensation expense per employee |

| Total HR investment/earnings |

| Total HR investment/revenues |

| Turnover by recruiting source |

| Turnover costs |

| Turnover rate by job category and job performance |

| Variable labor costs as percentage of variable revenue |

| Workers’ compensation costs |

| Workers’ compensation experience rating |

Source: Adapted from Dave Ulrich, “Measuring Human Resources: An Overview of Practice and a Prescription for Results,” Human Resources Management 36 (Fall 1997): 303–320.

We thus recommend that HR managers divide their key efficiency metrics into two categories: core and strategic. Core efficiency measures represent significant HR expenditures that make no direct contribution to the firm’s strategy implementation. Strategic efficiency measures assess the efficiency of HR activities and processes designed to produce HR deliverables. Separating these two helps you evaluate the net benefits of strategic deliverables and guides resource-allocation decisions. To see how this works, consider the following HR efficiency measures:

• benefit costs as a percentage of payroll

• workers’ compensation cost per employee

• percentage of correct entries on HR information system

• cost per hire

• cost per trainee hour

• HR expense per employee

The first three measures on the list would typically go in the core efficiency category. While certain benefit costs might give a firm an edge in recruiting high-talent employees, above-average benefit costs or workers’ compensation payments are legitimately considered expenses rather than human-capital investments. Likewise, transactional accuracy marginally improves employees’ work experience, but it has little strategic significance.

Now look at the last three measures. Notice that these expenditures can each be thought of as investments that would yield considerable strategic value. To determine their value, you would go through the seven-step process described in chapter 2, tracing the links between a strategic efficiency measure and the subsequent elements in the HR value chain. Again, the HiTech example of reducing recruiting cycle time applies. Tightening this cycle may well raise “cost per hire,” but in fact this practice is the first step in producing an HR enabler (stable staffing in R&D) that is essential to a key performance driver (R&D cycle time) in the firm’s strategy implementation process. This is a good illustration of how a firm might attend to both the benefits and costs of an HR deliverable (see the upper-right box in figure 3-2).

HR Deliverables

HR deliverable measures help you identify the unique causal linkages by which the HR system generates value in your firm. They are not necessarily expressed in terms of firm performance or dollars, but they should be understood broadly to influence firm performance. The test of their importance is that senior line managers understand their significance and are willing to pay for them.

One challenge in measuring the impact of such “upstream” drivers is to avoid measure proliferation. It is easy to think that everything is important, but if you do this, soon nothing is important. For measurement to matter, you have to measure only what matters. HR deliverable metrics that cannot be tied directly to your firm’s strategy map should not be included in the HR Scorecard. Once again, the process outlined in chapter 2 ensures that your HR measurement process has the proper foundation.

Choosing the appropriate HR deliverable measures depends on the role that HR will play in strategy implementation. At one extreme, HR deliverables could be characterized as organizational capabilities.3 Such capabilities would combine individual competencies with organizational systems that add value throughout the firm’s value chain.

Note, though, that a capability is so central to successful strategy implementation that it cannot be linked to just one performance driver. We know of a major international consumer-products firm that wanted to dramatically restructure its leadership capabilities. In management’s view, the firm with the best leadership talent would win in the marketplace, and this company intended to cultivate the best leadership talent in its industry. To achieve this goal, the management team developed its own competency model, which it considered proprietary. Next, it brought the executive search function in-house so that executive sourcing would reflect the proprietary competency model. Finally, the team added a powerful staffing-information system that would enable managers throughout the world to rapidly and effectively identify available managerial talent. No single element of this effort would constitute a strategic asset by itself, but taken together, these elements helped the firm develop a new organizational capability that senior line managers consider a key to the organization’s future success.

Thinking about HR deliverables in terms of organizational capabilities has a distinct appeal for human resources managers interested in underscoring HR’s strategic value. This is because such capabilities seem to offer a competitive advantage so compelling that other managers can’t help but acknowledge their strategic value. The problem is that without clear validation of that strategic value from the senior executive team, HR managers will have a difficult time making the case post hoc. Viewing HR deliverables as organizational capabilities is thus an appropriate but limited measure of HR’s strategic value. Identify this potential where possible, but also recognize that much of HR’s strategic value lies elsewhere. Most important, don’t try to puff up every HR initiative as a potential organizational capability. This kind of posturing will only undermine HR’s legitimate strategic contribution.

In short, we are talking about taking a different perspective on HR’s influence on firm performance. One approach is to focus on comprehensive people-related capabilities (such as leadership and organizational flexibility). It’s easy to imagine how such capabilities contribute to organizational success in general, and perhaps even in your own organization. They are also appealing because they immediately allow HR managers to recast what they are doing in “strategic” terms. While we don’t dismiss this approach out of hand, we encourage HR managers to understand its limitations as well. Most important, an approach that thinks only of HR deliverables in terms of organizational capabilities tends not to link those deliverables concretely to the strategy implementation process. In other words, the valuation of those deliverables requires much the same leap of faith that has historically undermined HR’s link to firm performance.

In contrast, with our seven-step model, measuring HR’s contribution does not require a direct leap from HR deliverable to firm performance. Instead there is a “causal logic” between HR and other non-HR business outcomes (such as R&D cycle time in HiTech), which line managers consider credible.

For this reason, as you structure the “HR deliverables” section of your Scorecard, you should focus more on HR performance drivers and HR enablers than on potential organizational capabilities. These measures represent the human-capital dimensions of discrete performance drivers in the firm’s strategy map. Their individual effects on firm performance are much smaller than that of an HR capability, but there are so many of them that, cumulatively, they represent a significant source of value creation. Table 3-3 shows a list of potential HR performance-driver measures for purposes of illustration.4 However, we would never recommend selecting a measure without following the earlier steps in our model.

Ideally, the “HR deliverables” section of your Scorecard will include some measure of the strategic impact of the deliverables you’ve identified. This could include estimates of the relationships between each deliverable and individual firm-level performance drivers in the strategy map. Or, in a more elaborate system, you could link the effects of the deliverables through the performance drivers and ultimately to firm performance. We saw this approach in the Sears story.

At this point, you will have defined the constituent elements of HR’s strategic impact on your organization. Yet even the HR deliverables represent just the hypothetical strategic influence of HR. Where possible, we encourage human resource managers to try to establish the actual impact of these deliverables on firm performance. This is the last piece of the sophisticated HR measurement system described in chapter 2. It allows you to confidently make precise statements such as “HR deliverable a increased x by 20 percent, which reduced y by 10 percent, which in turn increased shareholder value by 3 percent.” We discuss this aspect of designing your HR measurement system in more detail in chapter 5.

BASING THE HR SCORECARD ON THE HR FUNCTION

Our approach to HR performance measurement has been to adopt as comprehensive a definition of HR as possible, hence our emphasis on what we call the HR architecture. This has involved both a somewhat different perspective on “HR” in the firm and some new ideas about the important dimensions of HR’s performance. Making the leap from little or no performance measurement for HR to the concept of measuring the performance of the HR architecture can be daunting. Some firms may be more comfortable developing a Scorecard for the HR function as an interim step in this process. While we believe that the benefits of a more broadly focused Scorecard are compelling, some very good examples of HR Scorecards in practice have been organized around the HR function.

Figure 3-4 illustrates a graphical depiction of GTE’s HR Scorecard. Here the HR function is viewed as an organizational unit that can be analyzed in terms of the leading and lagging indicators associated with a Balanced Scorecard. In this approach the “Operations” and “Customers” are not the larger operations or customers of GTE, but rather the operations or customers of GTE’s HR function. This choice makes it more difficult to explicitly link HR to strategy implementation through the Scorecard, but it is a reasonable decision given that, at the time, the larger organization had not developed a strategy map as part of a corporate-wide “balanced” performance management system.

Table 3-3 HR Performance-Driver Measures

| Access to business information to facilitate decision making |

| Adherence by the workforce to core values, such as cost consciousness |

| Average change in performance-appraisal rating over time |

| Change in employee mind-set |

| Climate surveys |

| Consistency and clarity of messages from top management and from HR |

| Customer complaints/praise |

| Customer satisfaction with hiring process |

| Degree of financial literacy among employees |

| Degree to which a “shared mind-set” exists |

| Diversity of race and gender by job category |

| Effectiveness of information sharing among departments |

| Effectiveness of performance appraisal processes for dealing with poor performers |

| Employee commitment survey scores |

| Employee competency growth |

| Employee development/advancement opportunities |

| Employee job involvement survey scores |

| Employee satisfaction with advancement opportunites, compensation, etc. |

| Employee turnover by performance level and by controllability |

| Extent of cross-functional teamwork |

| Extent of organizational learning |

| Extent of understanding of the firm’s competitive strategy and operational goals |

| Extent to which employees have ready access to the information and knowledge that they need |

| Extent to which required employee competencies are reflected in recruiting, staffing, and performance management |

| Extent to which employees are clear about the firm’s goals and objectives |

| Extent to which employees are clear about their own goals |

| Extent to which hiring, evaluation, and compensation practices seek out and reward knowledge creation and sharing |

| Extent to which HR is helping to develop necessary leadership competencies |

| Extent to which HR does a thorough job of pre-acquisition soft-asset due diligence |

| Extent to which HR leadership is involved early in selection of potential acquisition candidates |

| Extent to which HR measurement systems are seen as credible |

| Extent to which information is communicated effectively to employees |

| Extent to which the average employee can describe the firm’s HR strategy |

| Extent to which the average employee can describe the firm’s strategic intent |

| Extent to which the firm shares large amounts of relevant business information widely and freely with employees |

| Extent to which the firm has turned its strategy into specific goals/objectives that employees can act on in the short and long run |

| Extent to which top management shows commitment and leadership around knowledge-sharing issues throughout the firm |

| Percentage of employees making suggestions |

| Percentage of female and minority promotions |

| Percentage of intern conversion to hires |

| Percentage of workforce that is promotable |

| Percentage of repatriate retention after one year |

| Percentage of employees with experience outside their current job responsibility or function |

| Percentage of retention of high-performing key employees |

| Perception of consistent and equitable treatment of all employees |

| Performance of newly hired applicants |

| Planned development opportunities accomplished |

| The ratio of HR employees to total employment |

| Requests for transfer per supervisor |

| Retention rates of critical human capital |

| Success rate of external hires |

| Survey results on becoming “the” employer of choice in selected, critical positions |

Source: Adapted from Dave Ulrich, “Measuring Human Resources: An Overview of Practice and a Prescription for Results,” Human Resources Management 36 (Fall 1997): 303–320.

The “bubbles” in figure 3-4 represent HR’s objectives for each level of the Scorecard. These in turn are linked to measures at both the enterprise and SBU level (see table 3-4). Table 3-4 links the HR Scorecard at the SBU level with the HR Scorecard at the enterprise level. The directional arrows correspond to a strategy map for the HR function and tell the story of how GTE HR will implement its functional strategy. This HR linkage model does not have the kind of direct linkage to strategic performance drivers that would be possible if a larger Balanced Scorecard existed for the entire enterprise. Nevertheless, there are at least three points where the HR function Scorecard would tend to connect with the larger organization’s strategy implementation efforts.

First, recall from chapter 2 that GTE HR developed five strategic thrusts for its HR strategy after close consultation with the organization’s business leaders. The foundational role of these five strategic thrusts is reflected by their location at the bottom of the HR linkage model (see figure 3-4). Second, the HR function Scorecard focuses on more than efficiency goals. The two objectives (maximize human capital and minimize HR costs) in the financial category are an effort to capture both value creation and efficiency as drivers of firm performance. Finally, at the customer level the HR Scorecard identifies strategic support for business partners as a key objective. This too should have the effect of improving the alignment between the efforts of HR managers and the business problems faced by line managers.

We began this chapter with the observation that a well-developed HR Scorecard should allow HR managers to do a better job of managing HR as a strategic asset, as well as provide a better demonstration of HR’s contribution to firm performance. In organizations that have not gone through the systematic development of a strategy map describing strategic performance drivers and opportunities for HR, it becomes more difficult to aggregate the relationships that easily describe HR’s impact on firm performance. However, as GTE’s HR Scorecard demonstrates, even a functionally oriented Scorecard can serve to refocus the management decisions of HR professionals. GTE HR credits its Scorecard, and the associated change in perspective, with dramatically improved relations between HR and business unit managers.

Likewise, while our emphasis has been on measuring HR’s “strategic impact,” HR professionals have multiple roles, as Dave Ulrich has pointed out: strategic partner, administrative expert, change agent, and employee champion.5 If HR professionals want a Scorecard that broadly touches on each of these roles, the functional emphasis illustrated by the GTE Scorecard is a good starting point.

Figure 3-4 GTE HR Linkage Model

Source: Reprinted with permission of GTE Corporation.

Table 3-4 Measures for GTE HR Scorecard, by Objective

BENEFITS OF THE HR SCORECARD

In constructing an HR Scorecard, avoid the temptation to merely “fill in the boxes.” The key question to ask is, What would you like this tool to do for you? Or, put another way, How would you like managers outside of HR to think about your measures? We believe that the Scorecard offers the following benefits:

It reinforces the distinction between HR doables and HR deliverables. The HR measurement system must clearly distinguish between deliverables, which influence strategy implementation, and doables, which do not. For example, policy implementation is not a deliverable until it creates employee behaviors that drive strategy implementation. An appropriate HR measurement system continually prompts HR professionals to think strategically as well as operationally.

It enables you to control costs and create value. HR will always be expected to control costs for the firm. At the same time, serving in a strategic role means that HR must also create value. The HR Scorecard helps human resource managers to effectively balance those two objectives. It not only encourages these practitioners to drive out costs where appropriate, but also helps them defend an “investment” by outlining the potential benefits in concrete terms.

It measures leading indicators. Our model of HR’s strategic contribution links HR decisions and systems to HR deliverables, which in turn influence key performance drivers in the firm’s strategy implementation. Just as there are leading and lagging indicators in the firm’s overall balanced performance measurement system, there are both drivers and outcomes within the HR value chain. It is essential to monitor the alignment of those HR decisions and system elements that drive HR deliverables. Assessing this alignment provides feedback on HR’s progress toward those deliverables and lays the foundation for HR’s strategic influence.

It assesses HR’s contribution to strategy implementation and, ultimately, to the “bottom line.” Any strategic performance measurement system should provide the chief HR officer (CHRO) with an answer to the question, “What is HR’s contribution to firm performance?” The cumulative effect of the Scorecard’s HR deliverable measures should provide that answer. Human resource managers should have a brief, credible, and clear strategic rationale for all deliverable measures. If that rationale doesn’t exist, neither should the measure. Line managers should find these deliverable measures as credible as HR managers do, since these metrics represent solutions to business problems, not HR problems.

It lets HR professionals effectively manage their strategic responsibilities. The HR Scorecard encourages human resource managers to focus on exactly how their decisions affect the successful implementation of the firm’s strategy. Just as we highlighted the importance of “employee strategic focus” for the entire firm, the HR Scorecard should reinforce the strategic focus of human resource managers. And because HR professionals can achieve that strategic influence largely by adopting a systemic perspective rather than fiddling with individual policies, the Scorecard further encourages them to think systemically about HR’s strategy.

It encourages flexibility and change. A common criticism of performance measurement systems is that they become institutionalized and actually inhibit change. Strategies evolve, the organization needs to move in a different direction, but outdated performance goals cause managers and employees to want to maintain the status quo. Indeed, one criticism of management by measurement is that people become skilled at achieving the required numbers in the old system and are reluctant to change their management approach when shifting conditions demand it. The HR Scorecard engenders flexibility and change because it focuses on the firm’s strategy implementation, which constantly demands change. With this approach, measures take on a new meaning. They become simply indicators of an underlying logic that managers accept as legitimate. In other words, it’s not just that people get used to hitting particular sets of numbers; they also get used to thinking about their own contribution to the firm’s implementation of strategy. They see the big picture. We believe that that larger focus makes it easier for managers to change direction. Unlike in a traditional organization, in a strategy-focused organization, people view the measures as means to an end, rather than ends in themselves.

SUMMARY: TIPS FOR MANAGING WITH THE

HR SCORECARD

Building an HR Scorecard should not be considered a one-time or even an annual event. To manage by measurement, human resource leaders must stay attuned to changes in the downstream performance drivers that HR is supporting. If these drivers change, or if the key HR deliverables that support them change, the Scorecard must shift accordingly. In building an HR Scorecard for your own company, you therefore may want to include a component indicating how up to date the HR deliverables are.

The same strategic perspective that guides the construction of the HR Scorecard should also guide the management of HR. In particular, human resource staff should keep line managers continually informed of the status of HR deliverables. Feel free to also invite line managers to identify potential deliverables on their own. This is all part of forging a powerful new partnership.