Introduction

I was seven years old when my mother showed me her most treasured jewels. Taking my hand in hers, she walked me through the giant oak doors of our town library where she showed me the Orange Books, biographies of historical men and women of achievement. Certainly, there were far fewer books of women than men, but there they were—women of achievement on the library shelves, books of the same size, same covers, different stories. My mother's most treasured gift for me was the library card that allowed these stories to be mine—stories which I continue to hold in my memory to this day—Amelia Earhart, Clara Barton, Marie Curie and Jane Addams, to name just a few.

I've been fortunate to have learned from a host of women leaders: teachers, primarily, but also advisors, colleagues, peers, caretakers, authors, friends, and relatives. A few women have inspired me even though I have never met them or have only “met” them through e-mail.

As an adult, I was directed by a friend to the powerful stories of twenty-five women of achievement in Written By Herself: Autobiographies of American Women: An Anthology by Jill Ker Conway. I still recall the story of the woman who told her brother, a medical school student, to return home each night and teach her everything he learned each day because women were neither accepted in medical school nor certified as doctors.

A woman corporate director pointed me to the stories in another book, The Door in the Dream: Conversations with Eminent Women in Science by Dr. Elga Wasserman, consisting of interviews with eighty-six women who had been elected to the National Academy of Sciences (five percent of the total membership by 2000).

The common thread, guiding my own career and experience, is that there are many women leaders who inspire us, many women of achievement whom we might follow, many women into whose “tall heels” we might step.

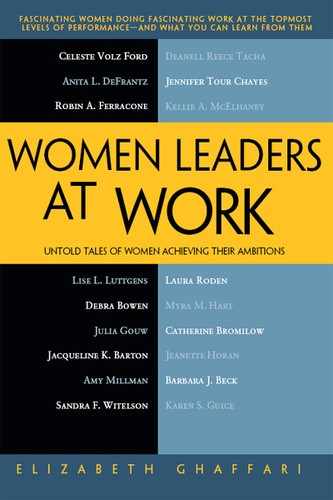

This book was motivated by the question, “Are we hearing about the women who are in leadership, today?” By our tunnel-vision focus on a few media headliners, we miss the thousands of talented, competent, and outstanding women of achievement in myriad other public and private companies, in science, medicine, law, venture and investment entities, government and politics, academia and education, and in major philanthropic endeavors.

Our challenge is to expand the writing, reporting, and interviews with these very interesting women. That's what this book is about—telling stories, learning lessons, experiencing the wonder, once again, as I did once before when my mother, walking through the great doors of our town library, shared with me the joy of intellectual curiosity. Enjoy with me, once more, the wonderful true tales of women leaders at work, succeeding in their own very special way at whatever they choose to accomplish.

What are the lessons that these women provide? First, they are everywhere. It was easy to locate talented women in leadership and to research their backgrounds and careers.

In the example of aerospace engineer, Celeste Volz Ford, CEO/chair of Stellar Solutions, I found enthusiasm for her career and the contagion of her personal choices. Women like her often wanted to talk less about themselves as leaders or their success and more about their companies or organizations as the vehicles for their leadership and proof of their success. I had heard her speak about the innovations of her company's benefit program before I knew much about her multi-company creations—Stellar Ventures, Stellar UK, and Stellar Foundation.

The women didn't always follow a straight line to their current position. They tended instead to find the niche of opportunity, the best route available, the unfettered path to success. They followed “their gut” and believed in their own intuition. Laura Roden, founder and managing Director of VC Privé, LLC, for example, began in corporate marketing, then finance, traversed the nonprofit and trade association world that related to venture investment before founding her own investment boutique bank.

Women in leadership weren't discouraged by their exceptional status. They didn't let being among a small headcount translate into being a small thinker. That was true of many of the women, but especially Deanell Reece Tacha, newly named dean of the School of Law at Pepperdine University and formerly judge of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in an era when women in law were more scarce than rare.

Consistently, the women demonstrated “possibility thinking.” It was something more than open mindedness. It was the capacity to think outside of the silos of professional, academic, or scientific limitations. They showed an ability to understand complementary disciplines and what those other perspectives might add to their own development or career. They were intrigued by the different ways their profession might grow and benefit through contact with other similar or dissimilar professional interests. That describes Dr. Sandra Witelson—professor, Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Inaugural Albert Einstein/Irving Zucker Chair in Neuroscience at the DeGroote School of Medicine, McMaster University (Hamilton, Ontario)—who developed “The Brain Bank” for comparative analysis of the brain's structure. It also describes Dr. Jennifer Tour Chayes, distinguished scientist, mathematician, co-founder, and managing director of Microsoft's NERD Center (New England Research & Development).

Those among them who chose to have children are extremely proud of their families and their individuality. Achieving the chimera of “work-family balance” was accomplished through the help of, and active delegation to, a valued support team. Not all first choices made the cut to a long-term relationship, because spouses are seen as equal partners who both deserve an appropriate amount of support and from whom an equal measure of support is essential for a successful career—personally and professionally.

Many women leaders at work include very creative professionals who have designed careers and fields of endeavor that did not exist before they came this way. Variations on traditional entrepreneurship, executive compensation, investment, corporate responsibility, and a host of other modern fields of endeavor happened because these women designed new products and services inside and outside of traditional professional parameters of their careers. Examples include Dr. Kellie A. McElhaney, Alexander Faculty Fellow in Corporate Responsibility, who essentially created the Center for Corporate Responsibility at the Haas School of Business, University of California at Berkeley in the face of “doubting Thomases” from faculty and business. This also describes Robin A. Ferracone, founder and executive chair of the executive compensation advisory firm Farient Advisors LLC, and chief executive officer of RAF Capital LLC, which invests in new products and services to support corporate human resource functions.

These are women of courage, plain and simple. Some saw rights that needed to be asserted, while others saw that appropriate protections ought to be put into place. These would include Anita L. DeFrantz, who challenged a president in our courts, advocating on behalf of athlete rights, and then became president of the LA84 Foundation and president and director of Kids in Sports, advocating on behalf of young athletes after the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, California. It would include Debra Bowen, currently secretary of state of California, who demanded that electronic voting systems provide the protections that a democratic electorate required.

Many took on significant challenges that might have cowered others, including Lise Luttgens, chief executive officer of the Girl Scouts of Greater Los Angeles, who took over the helm just as it consolidated six separate legacy councils on the eve of the organization's one-hundredth anniversary. It would also include Amy Millman, president of Springboard Enterprises, whose organization educates, sources, coaches, showcases, and supports high-growth, women-led entrepreneurial companies as they pursue equity capital for expansion. Not only did Julia Gouw, president and chief operating officer of East West Bank, lead that company to financial heights, but she also led peer executive women to invest in pilot programs benefitting women's health programs at a major university medical center.

All of these women are inspirations to other women who would become leaders. Two in particular have pushed the envelope in the advancement of women in academia by educating and facilitating the progress of young women faculty, women entrepreneurs, and women from business returning to re-career. They are Dr. Jacqueline K. Barton, Arthur & Marian Hanisch Memorial Professor and Chair, Division of Chemistry & Chemical Engineering at the California Institute of Technology; and Dr. Myra M. Hart, professor (retired) of entrepreneurship at the Harvard Business School at Harvard University. Dr. Barton has mentored young women in science who are now taking on top faculty positions in chemistry and chemical engineering at our major universities. Dr. Hart has trained and educated countless women in business through the vehicle of business-case development and her creation of MBA, executive education, and extension courses directly advising women in how to handle the challenges of re-careering.

In today's economy, it is a challenge to find individuals who marched up the corporate ladder, acquiring ever-increasing levels of responsibility all the way to the top. Certainly they mentioned mentors and coaches along the way, but usually they defined mentors as challengers, people who pushed them to test their wings and discover themselves. Not every step of advancement came with ease—sometimes they had to take more than one time at bat and at other times they had to step out of their comfort zone in order to stretch, grow, and reach their ambition.

The fascinating career of Jeanette Horan, CIO of IBM, highlights all of the major twists and turns of the technology industry over the past few decades. Catherine Bromilow, partner at PwC LLP, began her career in accounting in Canada and later helped to define the corporate governance area of emphasis in the US. Barbara J. Beck, CEO of Learning Care Group, provides interesting perspectives on the prerequisites for advancement—especially in this new global economy. Dr. Karen Guice, Principal Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, US Department of Defense, tells of her circuitous journey through medicine, to academia, and on to public policy positions, yet weaves a clear consistency throughout.

All of the women interviewed candidly shared their advice and insights for the next generation of women who might aspire to leadership. They truly wish those women success. Their enthusiasm and optimism was contagious, even as they recognize the challenges of today's more difficult economy. Some of these women have been through times that were far more adverse than today.

There are women in leadership who ran the gauntlet of being “The Only Woman” to take on a job, an education, or a career choice. Been there–done that. Most young women do not have to face those extremes today because the bridges have been built, thank heaven. What is required now is different from what had to be accomplished back then. Now, we can celebrate, and learn from, the achievements of talented women in just about every field of endeavor. That is why this book was written.