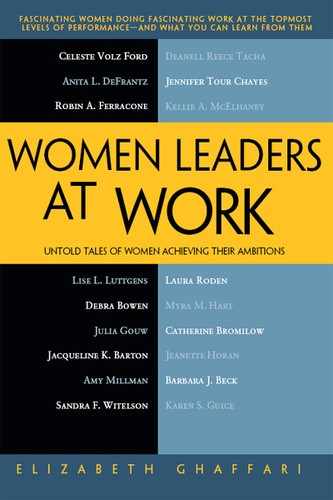

Laura Roden

Founder and Managing Director, VC Privé, LLC

Born in Los Angeles, California.

Laura Roden is founder and managing director of VC Privé, LLC, a boutique investment bank that, since its establishment in January 2007, has raised money for high-quality, alternative asset funds such as venture capital funds, hedge funds, and distressed debt funds. Her firm specializes in marketing funds to private investors, including high-net-worth individuals, family offices, foundations, endowments, and independent financial advisors. Ms. Roden holds Series 7, 66, and 79 licenses to sell securities and provide investment advisory services.

Previously, Ms. Roden was managing director of The Angels’ Forum, a leading association of individual and corporate early-stage investors, and was president and CEO of the Silicon Valley Association of Startup Entrepreneurs (SVASE), the largest nonprofit in Northern California dedicated to helping technology entrepreneurs. At both entities, she was responsible for dramatic increases in membership, deal flow, events, volunteers, sponsorship, and service offerings. During this period, she was also a lecturer in the Department of Accounting and Finance at the College of Business at San Jose State University (2001–2004).

Earlier in her career, Ms. Roden spent a decade in key executive-management roles at several emerging technology companies, including PowerTV (1997–2001) as chief financial officer and vice president of finance and administration; Whalen & Company (1996) as director of operations for the Western Americas; Vicarious, Inc. (1994–1996) as chief financial officer; and US Media Group (1992–1994) as co-founder and principal.

Ms. Roden began her active involvement in new technologies at Chronicle Publishing Company (1985–1992), where she spent seven years as CFO of the television broadcasting division and general manager of the cellular telephone group.

Earlier, she was a senior management consultant at Touche Ross & Co. (now Deloitte), an associate product manager for new products at HP Hood, and an assistant director of media and market research at Hill Holliday.

Currently, Roden is active in the Harvard Business School Angels and the Angel Capital Association. She is on the steering committee of the San Francisco Jewish Community Federation’s Business Leadership Council (BLC) and on the Northern California Education Committee for 100 Women in Hedge Funds.

She was named as one of the “most influential women in Silicon Valley” by the San Jose Business Journal. In August 2011, Ms. Roden was appointed to the board of directors of Heritage Bank of Commerce and its parent corporation, Heritage Commerce Corp., headquartered in California.

Ms. Roden received her undergraduate degree in English Language and Literature from Harvard University (1979) and her MBA from Harvard Business School (1983).

Elizabeth Ghaffari: Can you tell me a little about your early years? Where were you born?

Laura Roden: I was born and raised in Los Angeles and lived there through high school.

Ghaffari: How did you come to go to Harvard?

Roden: I had always heard that Harvard was the best place for an education. I saw an advertisement for a summer school program there, so I went to summer school there and just loved it. I worked in the Boston area in between college and business school, and I stayed for business school.

Ghaffari: How did you get your first job?

Roden: It was a chain of introductions. The year before I graduated from college, I worked in New York during the summer for an ad agency, Compton Advertising. I got that job through a friend who knew that I wanted to work in advertising. There, I met a number of people who were able to give me referrals after I graduated and was looking for a career position in advertising.

One referral was to HP Hood, a big dairy-products company in Boston. They needed someone to do market research for consumer products—leading focus groups, designing questionnaires, and analyzing results. It was not long after they lost their research manager, and they only needed a few projects done, but I did the work well enough that they recommended me to their ad agency, Hill Holiday Advertising, which also was looking to hire market research people. I spent a few months working there, but a large portion of my time was on the Hood account, so Hood hired me back full-time just to work for them on market research.

My first jobs in market research were very helpful—it’s a great background for every business.

Ghaffari: What made you decide to go back to Harvard Business School after the HP Hood assignment?

Roden: I had already been accepted under the deferred admission program, which is a fairly typical route into Harvard Business School for those applying directly out of college and who have not yet established prior work experience.

Ghaffari: What was your first job after business school and how did it come about?

Roden: While I was at Hood and, later, while in the business school, I became very interested in food companies and the food industry. I read an article about a company called Williams-Sonoma that was going into the food business. At the time, they were into housewares only, but the owner had become enamored with the food business. He had acquired US rights to Il Fornaio, the Italian bakery concept, and he was starting to open a chain of restaurants. They began as bakeries and then blossomed into restaurants.

I contacted the owner, Howard Lester, because I was very excited about that concept. I asked if I could come and work with him on that.

He hired me for a summer job in San Francisco. He also had me do some projects for Williams-Sonoma. One job in particular was doing a logistics analysis, studying the movement of goods from warehouse to stores. They ended up hiring Touche Ross & Co. to implement a solution, including a whole new software system. I got to know Touche Ross through the process of helping transition my work to their system. At the end of that project, Touche Ross invited me to come back to work for them in their San Francisco office, which I did for two years.

Ghaffari: How did you get your next job at Chronicle Publishing?

Roden: I was hired by the CFO of the broadcast group at Chronicle Publishing, initially as vice president of planning. And then after a couple of years there, he left, and I became chief financial officer of that group. Then the general manager of the cellular telephone business left, and I took over that job as well.

Ghaffari: So, a little bit of serendipity. Were there any mentors in that evolution of your employment?

Roden: Yes, I would say that both of the people for whom I worked directly definitely were mentors. The CFO of the broadcast group was very helpful and supportive. And then when he left and I was promoted to CFO, the person to whom I reported, the president of the broadcast group, also was very supportive.

Ghaffari: Can you tell me a little about US Media Group and how you came to that position?

Roden: I had been at Chronicle for seven years when the CEO of the broadcast group—to whom I reported—decided to leave. He invited me to join him in starting a new media company. US Media was a content company for interactive television, providing user information content for distribution via interactive television. Three of us left Chronicle to start US Media.

The closest thing, by comparison today, would be what you see with My Yahoo!—where you sign up with Yahoo! to get information on several topics that interest you. You set up your own channel for news and information to be sent to you via the internet. We had an idea to do a similar thing over television.

Ghaffari: What happened to the company?

Roden: This was 1992 to 1994, and we were very much ahead of our time and the technology. We were developing content, but the distribution channels were not yet viable. The actual interactive television infrastructure, the hardware, wasn’t available to carry the content we had developed. We ended up shutting the company down after two years.

For the next couple of years, I worked as the chief financial officer of another start-up company called Vicarious, Inc., which was the closest thing to interactive television—educational and entertainment content for interactive CD-ROMs. That was the cutting-edge technology for interactivity at that time.

Ghaffari: Do you consider yourself a leading-edge kind of person?

Roden: Actually, yes. I was going to qualify that by saying “after Chronicle,” but at Chronicle I was very deeply involved in the cellular telephone business, which was also very leading edge back then. It was brand-new.

Vicarious was in Silicon Valley. We ended up shutting that company down as well. Too early again.

So I did some CFO consulting for PowerTV, and then The Whalen Group hired me full-time. They were a wireless telecommunications project-management company located in the East Bay of the San Francisco area, but involved in projects all over the world. My responsibility was western North America, including both the western United States and western Canada, and South America. That’s where I traveled a lot and gained some global experience.

About six months after I joined Whalen, they sold the company but offered me the job of divisional CFO. Meanwhile, PowerTV was offering me the job to come back and be full-time CFO there. I decided to go back to PowerTV.

Ghaffari: What was the technology at PowerTV? Was it embedded technology or was it content development?

Roden: It was an operating system embedded in set-top boxes. PowerTV was sold to Scientific Atlanta, which was later acquired by Cisco. I was the CFO and VP of finance and administration.

After we sold PowerTV, I made a commitment to Silicon Valley Association of Startup Entrepreneurs to run that organization for a year. At the same time, I started doing some teaching—just for fun—as a lecturer in the finance and accounting department of the business college at San Jose State University. I ended up doing both of those for about four and a half years.

Ghaffari: How did you get that SVASE position?

Roden: I was on the e-mail list for the Forum for Women Entrepreneurs, which had posted an ad for the CEO position at SVASE. I had been one of the founding board members of FWE—which is now called Watermark.

I ended up being CEO/president of SVASE for the next four years. It was a big change to run a nonprofit where a major part of your job is fundraising. That taught me that I was both good at, and enjoyed, fundraising because I understood the customer and believed in the product.

Ghaffari: Was your primary responsibility there in an executive director role? What were some of your key accomplishments?

Roden: Yes. Regarding accomplishments, we tracked several metrics. First of all, sponsorship was an important performance metric. When I started, SVASE was bringing in about $10,000 a year in sponsorship. When I left, it was $300,000 a year. Another key metric was the mailing list. When I started, we had about two thousand people on our e-mail list. When I left, it was about twenty thousand people. When I started, we had about twenty volunteers. When I left, we had about two hundred and fifty volunteers, meaning people actively engaged in running parts of the organization. At the beginning, we were doing two or three events per month. When I left, we were doing ten to twelve events per month.

So, SVASE grew in every way. They had never had an advisory board before, so we created a thirty-member advisory board.

Ghaffari: Would you say that SVASE was the place where you really first started to get involved in meeting the combination of venture capitalists, investors, and entrepreneurs? Did you like this experience? Was it interesting?

Roden: Yes, I would say so. The most important part of this experience, for me, was my exposure to fundraising, which essentially was sales. That was the big difference for me. Before this, I had been an entrepreneur. I had participated in raising money from venture capitalists. Obviously, I connected with venture capitalists on a much broader scale, in terms of the number of interfaces, at SVASE. But the really big difference from anything I had ever done before was what I call sales experience—actually being on the front line raising money. Before that, I had always been in a role that faced internally—counting the money as a CFO. At SVASE, I was down on the front line facing the community and asking for money. That was the really major change.

Ghaffari: That’s a very tough job. How did you figure out how to do it well? What were some key factors of your success?

Roden: I think that the key was in really understanding the value proposition for the customer. I understood the value to the entrepreneurs. I understood the value to the banks, to the attorneys, to the accountants. I understood the value proposition to each constituency we were addressing because I had been in their shoes before. So, it was a very natural transition to be able to explain why they should be involved. If it had been in an area where I really didn’t understand the value proposition, it would have been impossible. I never could have done it. But it was really based on the experience I had already acquired. I understood why we were offering something valuable.

Ghaffari: Why did you switch to The Angels’ Forum?

Roden: One of my advisors when I was at SVASE was a woman who founded The Angels’ Forum—Carol Sands. She recruited me for more than a year to come run The Angels’ Forum because she had seen the success we had had at SVASE. She thought The Angels’ Forum would benefit from that kind of performance improvement. Eventually, she convinced me to switch. It interested me as another new challenge, something different. I had been at SVASE for about four years—they were fairly stable and it was a nice time to try something new. I was managing director there for about two years.

Ghaffari: And tell me some of the metrics of that experience.

Roden: There were two jobs there. My first job was running The Angels’ Forum, which had been around for a long time but had gone through its ebbs and flows in popularity. The first goal was to rebuild the membership of the group, meaning the number of angel investors. My second job was to improve the deal flow, meaning the number of quality deals presented to the group. Those two metrics go hand in hand. If you don’t have good deals, members won’t come, and if you don’t have members, deals won’t come. So those were my primary goals, and we made very significant improvements in both areas.

We ramped up the number of deals. When I came in, they were having trouble ensuring that members would see at least one interesting new deal per week. When I left, we had four new deals every week, as well as a waiting list. So the deal flow was ramped up.

There were a lot of things we implemented that improved deal flow, but the visible result was that there were more than enough really quality deals to keep everyone quite busy and engaged.

On the membership side, we had a declining number of members when I started—down to the high teens. The goal of the group was twenty-five members, but I rebuilt it to over thirty members with a waiting list.

Ghaffari: What did you do that was of significance to enhance the number of deals and the membership?

Roden: I would say there were two different things. One was pure process improvement, which kind of goes back to my business school and Touche Ross consulting experience. We had problems just with our basic processes. People would apply with deals they wanted to be seen, but their applications would be lost. Deal proposals wouldn’t be read by the right people or on a timely basis. Or they wouldn’t be read at all. Improvements to those kinds of basic logistical questions made the whole application process flow better. That was just the pure and simple administrative stuff.

The other side of it, the angel side, suffered from the simple fact that there was no one in charge of rebuilding the membership. No real effort had been made. The processes that we put into place first asked for referrals for potential members from existing members. Then we followed up on those referrals and put into place a process to explain The Angels’ Forum and its value. We developed a lot of new marketing materials to explain the group to potential members.

Another important piece—partly process, but partly content—involved improving the quality of the experience for members. We put in some guidelines, rules that were targeted at involving people much more deeply in the process, to ensure that every screening committee had a diversity of members on it and that no one was left out of the process. We standardized our term sheets so that there was less confusion. As a result, people felt more empowered to negotiate a deal.

In essence, almost all of our changes were process-oriented, but more importantly, we looked at all the different things that had become impediments to a positive deal experience there. We just removed those obstacles.

Ghaffari: Sometimes it looks logical after you’ve fixed it. What made you decide to go off on your own and create VC Privé. What triggered that decision?

Roden: A lot of members were interested in investing in venture capital funds, and a lot of people that I interviewed to be potential members were interested in investing in venture capital funds. Even though there was enormous interest, it became apparent that it was very difficult to find out which venture capital funds were available, how to perform due diligence on them, how to invest in them, how to connect with them.

Initially, we thought we might form our own venture capital fund. But, I decided that the real need in the marketplace was for a channel between private investors and venture capital funds. Very much like The Angels’ Forum, which was a channel between private investors and individual company deals, VC Privé would be the vehicle to help private investors get into venture capital funds. That was the idea for VC Privé, and the name VC Privé captures that idea because it’s a bridge between VC, venture capital funds, and private investors.

I was very excited about the concept. I knew a lot of investors by that time who were very interested in it, so that’s why I started it.

Ghaffari: In any of your SVASE or Angels’ Forum or VC Privé experience, did you have a large number of women investors or was it mixed gender? Was it dominantly men?

Roden: In terms of investors, there were almost no women.

Ghaffari: How has your business evolved since you founded it?

Roden: When VC Privé first started, our focus was pretty narrow. It was just the bridge between the angel investors, private investors, and VC funds. But once I started doing that, then other funds started calling and saying, “Look, if you raise money for VC funds, why don’t you raise money for my fund? I’m a hedge fund, or I’ve got a real estate fund, or a debt fund.” Ultimately, many different kinds of funds came to us, and bit by bit we said, “Okay, that’s reasonable” or “No, thank you,” but we expanded the variety of funds we represent. And then, on the investor side, when we started all the relationships with private investors, they started introducing me to their money managers, and then the money managers started introducing me to foundations and endowments. So, that side expanded as well in terms of the number and variety of investors we reach out to. But the core original concept is simple. It was just that we are a bridge between investors and funds.

Ghaffari: So you really have grown through reputational expansion because individuals like what you’re doing and others want to be part of this relationship.

Roden: Yes, that’s exactly how we grew.

Ghaffari: What motivated you at the beginning? Is it different from what motivates you now?

Roden: I have always been motivated by interesting opportunities where I can add special value, make money, and keep intellectually and creatively challenged. Starting VC Privé in 2007 was a new and different challenge. It was the first time I headed a business that I conceptualized, founded, structured, and built, instead of joining a preexisting team. It was the culmination of all my prior years’ experiences coming together to help me identify a market need that was not being filled. I started VC Privé with a clear understanding of needs, values, and customers.

Ghaffari: I’ve seen different numbers that describe the range of your typical investment at VC Privé. How would you describe it?

Roden: One measure is the size of the investment that a typical single investor might put into one fund—that would range from $500,000 to $5 million. That’s the size of an individual check, so to speak, that someone might write.

The other measure is the fund size, the total fund, once you get all the investors together. The smallest fund we’ve represented was $10 million, while the largest fund we've represented was $3.5 billion total fund size.

Ghaffari: How did you build your advisory board?

Roden: That was an interesting process in and of itself because, first of all, I started building the advisory board by selecting people who were experts in the private fundraising industry. But, I was completely turned down by those I invited.

Then I went to a mentor of mine, a friend who gives me good advice. He suggested that I was going about it all wrong—that I shouldn’t plan an advisory board of people in my industry because they would feel that they were, in essence, competitors. Instead, I should develop an advisory board of people who were experts in the types of investments we’d be representing. So, I changed that direction and found that it pulled together very rapidly. It was a very good change in approach. We ended up with a lot of very talented expertise to advise us.

Ghaffari: I noticed references to Viant Capital and EB Exchange Funds on your web site—are those examples of the kinds of funds with whom you do business?

Roden: In my business, everyone needs to be licensed by The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority while the Securities Investment Protection Corporation protects investors by providing insurance for brokerage accounts if a firm fails or goes bankrupt or unauthorized trading is suspected.

There are different levels of licenses. I’m licensed at the registered representative level. Viant Capital is licensed at the broker level. Eventually, if VC Privé becomes large enough, we’ll be licensed at the broker level, too, but right now it doesn’t pay to do that. The cost-effectiveness of that is such that you need to be much larger to have your own brokerage license. Viant has the brokerage license, and we’re affiliated with them. That’s specifically a regulatory relationship.

EB Exchange Funds was my first client in this business. We raised one of their funds for them. EB Exchange runs a series of private equity exchange funds.

Ghaffari: You call yourself a “boutique investment bank.” How large is that industry?

Roden: There are quite a few—maybe a hundred thousand? They go by a number of different names. Many call themselves boutique investment banks, most of whom raise money for companies rather than funds. Each boutique has its niche, and our niche is specifically representing private funds. There are very few that do that.

Ghaffari: You said one of the challenges you faced was being in the middle of a divorce, having a toddler, and managing your career. At what point did you go through that?

Roden: That was right when I was leaving Chronicle to start US Media Group, so it was right in the middle of my first start-up. I had my daughter the last year I was at Chronicle. She was an infant then and then a toddler during the time I was doing the start-ups.

Ghaffari: Any insight as to how to manage that kind of a transition?

Roden: Getting really good help is key. We had a couple living with us, our nanny and her husband, for the first five years of my daughter’s life, so it was like having an extended family—almost like having grandparents living with us. It was invaluable.

Ghaffari: Are you married now? Is your husband involved in the company?

Roden: I’m married, but no, he has a completely different career.

Ghaffari: How do you manage family expectations or commitments?

Roden: Generally speaking, I set the expectations and commitments. I am an alpha-dog type, but if a family member wants to do something that I don’t want to do, that’s fine. I don’t try to control or monopolize other people’s time, just control my own environment.

Ghaffari: What do you tell your family about your vision, goals, and business interests?

Roden: They hear about them incessantly.

Ghaffari: How do they react?

Roden: Great! The more they understand what I’m doing, the more they feel we have in common. Since I work 80 to 90 percent of the time, if they didn’t have this commonality, we would be pretty remote.

Ghaffari: What are the most inspiring positive responses?

Roden: My daughter wanting to get an MBA and pursue a career in finance. My husband and daughter wanting to create businesses together with me.

Ghaffari: How did you address negative reactions, if any?

Roden: Usually if there is a negative reaction, it’s because I was too brusque or impatient in communications. I apologize a lot.

Ghaffari: Let’s go back to VC Privé. What were some of the key initial strategy decisions you made in starting VC Privé?

Roden: First, the decision to create an “institutional” rather than “sole proprietorship” structure, culture and image, including the decision to not name the company after me. Second, taking the time up front to get the securities licenses in place. Third, investing in a polished web site and marketing materials. All of those helped immensely, plus the decisions not to take outside capital from investors and to build an advisory board of industry experts.

Ghaffari: What keeps you up at night? Did you ever want to quit? What kept you going?

Roden: The main issue that concerns me is that there is always so much more to do, with every day and every minute. Our opportunities are huge. There is a constant urgency to prioritize time and resources, moving forward as fast as possible. The market may change, the economy may change, the competition may change—and we need to be ready to take advantage of every moment.

The second thing I’m concerned about is the burden of counterproductive, destructive, misconceived regulatory issues that harm our industry at all levels, for both large and small firms.

Ghaffari: How would you describe your relationship with investors? Or partners? Or colleagues?

Roden: There are no external investors in VC Privé as a company. I have not taken outside money, although there were two offers. I believe service firms such as ours can and should be successfully bootstrapped. They do not need capital to grow. I have no partners. With colleagues, the important issue is always finding a shared strategic vision. How big do we want to grow? Do we want a flat/regional or pyramid/centralized structure? What kind of clients do we want—are we Tiffany’s or Wal-Mart?

Ghaffari: How do you view your competition?

Roden: I’d describe my approach to competitive challenges as “disciplined.” I evaluate the strength of the competitor and the importance of the challenge critically. Most challenges fail on their own accord, so the ultimate decision is to just keep our eyes focused on our priorities and excellence in execution. Sometimes a challenge opens our eyes to a new way of doing business that we should be considering. In either case, competitive challenges are never ignored.

Ghaffari: What is your view from your current position? Where are you going to be in the next five to ten years with this company?

Roden: You know, I don’t want to jinx anything, but at some point I anticipate we’ll sell the company. That’s typically what happens to companies in this industry. They get bought by larger companies. That might be what could happen—what most likely will happen.

Ghaffari: You also are involved in other outside interests, such as Harvard Angels, Angel Capital Association, and 100 Women in Hedge Funds. Are those the primary ones where you are currently involved?

Roden: Those are the primary ones that are directly related to the investment industry. I’m also very involved in a nonprofit called the Business Leadership Council, which is more philanthropic.

Ghaffari: That’s the San Francisco Jewish Community Federation?

Roden: Yes, and their mission is to enable those leaders who are already in business to come together and inspire each other to do more philanthropy.

Ghaffari: In your business, are there many women of wealth who are private investors?

Roden: No, because primarily we deal in a niche that is very much risk capital—alternative assets. The term “alternative assets” refers to investments that are unusual, not mainstream publicly traded stocks and bonds. They are types of investments that are not broadly known or understood. In my experience, the people who invest in these kinds of assets are very comfortable making independent financial decisions. They’re very confident in their own ability to assess investments. They are comfortable investing in things that are not mainstream. And those people are almost always men, typically men who are entrepreneurial and who have built their own businesses. These are people who have had success in their lives doing things that are unusual, taking risks, and relying on their own judgment. They feel comfortable applying the same values to their investing.

The women investors that I talk to are much more comfortable dealing with mainstream investments, almost always dealing with financial advisors, and especially some of the businesswomen I know turn over all of their financial decision-making to their husbands because they just don’t want to deal with it.

Ghaffari: Would you consider yourself a risk taker? Where are you on the risk spectrum, yourself?

Roden: Yes, I would say I have become much more comfortable with risk, particularly since 1992 when I was in the first start-up—which was a big decision point for me. Ever since then I have been much more comfortable with risk.

Ghaffari: Would you say your business is risky in and of itself in these economic times?

Roden: I don’t think my business is particularly more risky in these economic times compared to others. I don’t think it’s riskier than other businesses. Every new business has to make its own success. Certainly, running an entrepreneurial business is a riskier job than being part of a big company, but I don't see that this business is any riskier than any other small, growing business.

Ghaffari: You’re also involved in 100 Women in Hedge Funds. What is the nature of your involvement in that?

Roden: I’m on the education committee for the Northern California region. So, 100 Women in Hedge Funds is like a trade association for women involved in the hedge fund industry. Each region has an education committee that designs and operates the various regional activities.

Unlike The Angels’ Forum, which was something like operating a business, 100 Women in Hedge Funds is a trade association more like SVASE, which is all about putting together events, speakers and membership activities.

Ghaffari: Have you continued your involvement with the Forum of Women Entrepreneurs and Executives?

Roden: Not right now, no. I was on the board for many years, but I haven’t been on the board for many years. Occasionally I go to an event, but I don’t have any other role.

Ghaffari: How would you describe your decision-making style?

Roden: I think I am a very good decision-maker. First, I evaluate the importance of the decision. A decision about “what do we want for lunch?” has very low importance. “Should we hire this sales person” has much higher importance. I allocate a proportionate amount of time to collecting and considering the pros and cons. If I spend more than sixty seconds on a lunch decision, that’s too much. If it’s a key decision, I may consult many outside data sources, physically write down an outline of the ramifications, sleep on it for a few days, etc.

One shortcoming I have is that once I make a decision, I am very loath to change it. This can be a strength but also a real weakness.

Ghaffari: How do you define success?

Roden: If you feel satisfied with your accomplishments.

Ghaffari: How do you define your position as a leader?

Roden: I think a leader inspires others to action, whether for profit or nonprofit, whether for my mission or their own.

Ghaffari: Would you do anything differently if you were starting out today?

Roden: I would have taken voice lessons to improve the depth and gravitas of my delivery—a key weakness among many women.

Ghaffari: How do you advise women today who face the kinds of challenges you did? How can they work their way through or around them?

Roden: Persevere, persevere, persevere. Do not allow yourself to admit the possibility of defeat. Stay fit and sharp. Try to think six steps ahead on every move—yours and others. Don’t take your foot off the dock until you have identified a secure stepping stone.

Absolutely everyone goes through very tough times, so empathize with them. Ask people’s advice, but trust your own decisions. Share enough of your difficulties to solicit help, but not so much that it hurts your credibility.

Very importantly: If you really can’t afford the luxury of failure, there’s a much higher chance you’ll succeed.

Don’t waste time. Use every moment, either for business or for pleasure, intentionally. Lose your TV. Lose the YouTube URL. Have your assistant update your Facebook with your vacation pictures.

Save every contact that is at all meaningful, with notes on when and how you met, any key points of common interest, etc., in a database you can search by keyword.

If your spouse or partner is unsupportive, stop trying to fix them or blame yourself or deceive yourself or others as to why the relationship isn’t happy. You need and deserve support. Make this the ultimatum: “support me or lose me.” You would, presumably, do as much for them as well. If you’re not supportive of your spouse/partner, you’re doing them an injustice.

Ghaffari: What advice, especially, do you have for young women?

Roden: You have much more power than you think. Understand it, learn how to use it as quickly as possible, and find a female mentor who can train you in this.

Ghaffari: What do you see as the areas of greatest opportunity for young women professionals?

Roden: Anything where you are indispensable. The easiest way to get power, money, and position is to do the jobs that other people can’t do well—finance and sales. Avoid soft, non-measurable jobs like marketing, business development, human resources, PR, etc. You will be totally disposable and under-appreciated. Management may love you now, but management is subject to change without notice, and unless the metrics are there, you are dust.