CHAPTER 3

WHAT SCIENCE TELLS US

WE’RE ALL FAMILIAR WITH President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Depression-era assurance that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” Roosevelt understood how fear can paralyze, demoralize, and divide individuals and groups who need to pull together in the face of a collective threat.

When it comes to feedback, it’s not a collective threat we’re facing; it’s a collective opportunity to open new doors that lead to bigger and better outcomes. However, fear has long limited the important role that feedback should be playing in our working lives. And that fear is the result of feedback gone wrong. It’s paralyzed the flow of good, helpful communication; it’s demoralized well-intentioned people and, by extension, entire organizations; and it’s too often produced divisions instead of healing them. Why do we fear it, and how do we fix it? The answers to both these questions lie in understanding the evolutionary legacy that dictates our biological responses to intense physical or emotional situations. Armed with an awareness of the complex set of defense mechanisms we employ to avoid or escape those encounters, we can then retrain our minds and rethink our ways of interacting to take the fear out of feedback once and for all.

YOUR BRAIN ON FEEDBACK

Meet Steven, a smart, thoughtful, and talented fellow, and Mira, his equally capable and caring manager. One morning, Mira says, “I’ve got some feedback for you, Steven. Would you step into my office?” Hearing this sets Steven’s heart racing. His palms begin to sweat as his numb legs carry him toward Mira’s office. A series of questions, all negative, flash through his brain: Why me? What the heck is this about, anyway? Did I mess up or forget something? Is she out to get me? Is everyone in the office out to get me? Am I getting fired???

Steven and Mira have always had a cordial (if superficial) working relationship, and he has no logical reason to suspect her of ill will. So why is his reaction so extreme, so immediate, and so overwhelmingly negative? The answer can be found in the past—not only Steven’s, but all humankind’s as well.

Not everyone will react to a simple offering of feedback as dramatically as Steven has, but the fact is that most of us will experience some variation of his distress. Like too many of us, Steven’s brain has been conditioned to go into “fight, flight, or freeze” mode at the mere mention of the word “feedback.” Some of Steven’s previous experiences with feedback have been rough, so this moment sets off a powerful and rapid fear response in his amygdala (what we’ll call the “primitive brain”), which triggers his sympathetic nervous system to activate a powerful cocktail of stress hormones and neurotransmitters that prompt his body to go into hyperdrive.

This “fight, flight, or freeze” response is an evolutionary adaptation that was essential to the survival of the human species when massive predators and other existential threats were abundant. Your face flushes and your mouth dries out as blood flow is diverted from surface tissues to your arms and legs, and your muscles tense and tremble in anticipation of confronting or escaping the source of the threat. Your heartbeat and breathing accelerate, pumping oxygenrich blood through your system to fuel quick action. Your hearing sharpens, and your pupils dilate as a kind of tunnel vision kicks in, creating a hyperaware, highly reactive state.

It’s an extreme response shaped by eons of extreme circumstances. The problem is that our brains have evolved much more slowly than our society has. Sure, this acute stress response still serves its purpose if you’re escaping a burning building or taking fast action to avoid a car accident. But it can also be triggered when the threat is emotional and not physical, since the brain doesn’t always register them as different types of threats. And when our primitive brains respond to emotional triggers by prioritizing physical strength and narrowing our focus on survival over reason and emotional control, we’re liable to lash out, run for proverbial cover, shut down, or resort to appeasement (become a “pleaser”) in order to relieve the emotional discomfort that’s built up inside us. In any case, there’s a disconnect between who we’d like to be in that moment and who we show up as.

Not surprisingly, this disconnect spells disaster for Steven and Mira. Here’s what results:

ZERO TRUST. Since Steven feels threatened, his “fight, flight, or freeze” response kicks into high gear, so he’s not inclined to trust Mira. This creates a powerful, negative emotional imprint of this response. His brain stores this encounter for future reference, meaning the results of his next feedback experience might be even worse.

ZERO TRUTH. Stuck in this state, Steven will fail to see, appreciate, or process any legitimate feedback Mira tries to convey.

ZERO PERSPECTIVE. Steven may catastrophize. The human brain tends to make one thing into everything, especially when it comes to negative input. A suggestion on improving performance becomes Uh-oh, my career’s in trouble. A rejected idea is quickly translated into They don’t value me here.

Is there anything we can do to bring our calmest, most collaborative selves to the feedback table? As a matter of fact, there is, though the answer may seem counterintuitive. In order to free our minds to fully engage, we must calm the stress response. We will never be entirely free of it, but we can manage it in order to optimize our responses to feedback and the opportunities it presents. Look at it as getting out of our brains and into our bodies for a while. That means developing a keener awareness of our physical responses in the moment and learning how to influence them.

Each time we participate in a challenging conversation with greater calm and heightened self-awareness, we create or reinforce neural pathways in our brains that will allow for more positive responses under stress in the future. The better we get at handling our fear (in this case, the fear of feedback), the less threatening these situations become.

When you feel yourself getting caught in an emotional vortex, the goal is to shift as much of your attention as you can to your body and your senses for at least 10 seconds or for three full breaths. Easing fear, anxiety, and anger (common emotions when the primitive brain is fired up) by becoming consciously aware of your physical sensations requires that your prefrontal cortex (also known as the “wise brain”) be engaged. Science tells us that you can’t be “located” in both of these parts of the brain at once. In other words, you can’t simply think yourself out of the stress response. You must shift your awareness to your physical body in order to ease the stress response and allow your wise brain to regain control. Training our brains to build these new pathways and ingraining new, healthier habits doesn’t happen at the snap of a finger, so stay patient and positive as you explore the following suggestions for mitigating the “fight, flight, or freeze” response:

FEEL YOUR FEET. Flatten them hard into the floor. Feel your toes touching the ground. How do your feet feel? Soft? Numb? Warm? Tingly? Keep feeling the physical sensation as you slowly breathe in and out a few times.

LISTEN TO THE SOUNDS AROUND YOU. Shift your focus to the sounds around you. Can you hear the click of computer keys, or the murmur of traffic or chirping of birds outside? Listen. Focus your attention on these sounds and try to keep it there for 10 seconds.

RINSE AND REPEAT. You can groove new neural pathways by turning to these exercises anytime you feel stressed. With practice it should get easier and easier to shift your focus and clear your mind.

Shirzad Chamine, Stanford University professor and author of Positive Intelligence, calls practices like these “Positivity Quotient reps” and suggests we practice them for 10 seconds, 100 times a day. (Sound too daunting? That’s only about 15 minutes.)1

DON’T FORGET TO BREATHE

Here’s a slightly more complex exercise that may help you tamp down the agitating effects of the stress response. 4-7-8 breathing is a simple relaxation practice developed by Dr. Andrew Weil. Working from the lungs outward, techniques like 4-7-8 can rebalance the flow of oxygen in your body. This can come to your aid in a stressful feedback moment, and also provide daily relief from the accumulated stress and anxiety that can keep you from being at your best when taking in or giving feedback.

1. Rest the tip of your tongue against the roof of your mouth, right behind your teeth. Allow your lips to part.

2. Exhale completely through your mouth.

3. Next, close your lips, inhaling silently through your nose as you count to 4 in your head.

4. Then, for 7 seconds, hold your breath. (This may seem like a long time at first!) Holding your breath slows your heart rate and causes your body to relax and your mind to slow down.

5. Exhale through your mouth (go ahead, make it loud) for 8 seconds.

6. When you inhale again, you start another round.

Of course, the long-term solution for taking the stress response out of the feedback equation lies in the success of our movement to create a world where feedback is no longer a source of such anxiety. That’s not going to be easy, since fear finds so many opportunities to sink its claws into every member of the feedback ecosystem.

WHAT WE REALLY FEAR

Feedback is far from a life-or-death proposition. So why does it trigger such extreme reactions? What is the big F’ing deal about feedback, anyway? What exactly is the threat that lurks in the feedback shadows, firing up our primitive brains like a crouched saber-toothed tiger ready to pounce?

When we peel back the layers and look closely at what frightens us about feedback, it boils down to this: identity and connection. Yes, at the heart of our fear is our identity, and how that identity is shaped and reinforced by our connections to and affiliations with the rest of the world. What we truly fear are isolation, ostracism, and abandonment. And while isolation meant almost certain death for our ancestors, today the physical implications are considerably far less dire. Yet, for most of us, the desire to belong is a prime motivator. Humans are social beings; we instinctively want to be included and valued. The need to stay connected with and accepted by our communities drives our actions without our intellectual complicity.

So, what do we do? We seek protection.

We protect ourselves through avoidance, and we protect ourselves through distortion. We take false comfort in believing that what we don’t hear or don’t say can’t hurt us. We avoid seeking insights that we might not want to hear. We avoid sharing perspectives that might damage connections with those we hold in esteem (like our boss, for example, not the guy who just cut us off on the freeway). We avoid fully assimilating what’s been shared so we can manage the risk that it might challenge our ideas of who we are and how we’re perceived by the crowd or those whom we value. And often we distort what we hear to better fit our own frameworks and views, again with the aim of preserving our self-image and our connections. These behaviors or reactions are especially true when we’re unprepared for the critical feedback that comes our way.

Interestingly, this self-protective behavior prevents us from extending feedback at least as much as it prevents us from seeking it. Most of us don’t want to hurt those we care about, so we tend to delay or even completely avoid sharing a thought or an idea that we suspect might upset the recipient and potentially damage our relationship.

Let’s revisit our friends Steven and Mira, but this time, let’s consider Mira’s dilemma. What Steven doesn’t realize is that Mira has avoided this conversation for as long as she could. A recent project postmortem called out the shortcomings of Steven’s work on the project. The postmortem participants asked Mira to make sure Steven received the feedback. Intellectually, Mira knows that if she gives him this coaching it will help him be more impactful to the new project he’s working on. At the same time, she wants to maintain her status as a smart, savvy, and likable manager in the eyes of both her peers and Steven. So, though she’s the one who initiated this interaction and would appear to be in the driver’s seat, she’s confronting her own proverbial sabertooth. As the meeting draws closer and closer, the negative chatter in her head escalates: Am I sure that what I’m going to tell him is true and fair? What exactly did they want me to say again, anyway? I’m afraid this is not going to go well. What if he gets angry ? What if he quits? Maybe I’m not that good at managing people after all.

Fear and anxiety are clouding Mira’s judgment, so by the time she sits down with Steven, she’s made a set of assumptions that will make her ill-equipped to have a conversation that welcomes give-and-take and exploration. She’s considering one of two paths at this point:

• On Path One, she’s ready to “yell, tell, or sell” her way through the conversation and get out quickly. She’ll exit feeling a little adrenaline rush for getting that off her list and meeting her commitment to her peers. Steven, on the other hand, will leave smarting.

• On Path Two, she gives Steven some love, timidly slides in the feedback she wanted to share, then returns to more positive topics before wrapping up the conversation. She’ll leave hoping he got the message and relieved that she avoided any conflict. Steven will walk away perplexed over exactly what she was trying to get across and why.

Both paths lead to a lose-lose outcome. Steven and Mira each enter this interaction in fear’s grip, and fear wins out, creating a poor experience for both that will ultimately diminish any trust that may have existed between them. Because both are focused on avoidance, the main thing they end up avoiding is a healthy, productive dialogue. What occurs instead is a fiasco that reinforces their tainted notions of what feedback is.

WHY DO WE GO POSITIVELY NEGATIVE?

There’s plenty of science that explains why both Steven and Mira seem so resigned to listening to the worst version of their inner voice.

Here’s what we know:

• Our brains process negative information faster than other stimuli.

• Negative information has more influence in evaluations than positive information.

• We weigh negative impacts or outcomes more heavily than equivalent positive outcomes (e.g., we react more dramatically to losing 20 dollars than we do to finding 20 dollars).

• We’re more motivated to avoid bad definitions of ourselves than to seek good ones.

• Negative information gets far more processing time than good information.

• We form negative opinions more rapidly and are slower to let them go.

• We remember negative events far longer than we remember positive ones.

• In nearly every situation, research tells us that bad is stronger than good.2

It all boils down to this: events we perceive as bad produce more emotion, have bigger impacts, and longer-lasting effects. Why? It’s human nature, that’s why. Again, our instincts for self-protection play a big role. Our ancestors’ survival was dependent on their awareness of and speed at responding to negative signals, triggering them to take defensive action and seek self-preservation. Research also links our negativity bias to factors beyond our evolution, like the ways in which humans process and react to trauma, how we learn, and our impulse to adhere to social pressures. For our purposes, we don’t need to debate the causes. What’s important is to build our awareness of this phenomenon and understand how this knowledge can help us fix feedback.

Each of us can easily and quickly recall feedback that left us licking our wounds. This is often our negative bias at work. Overall, it’s likely that we’ve been on the receiving end of an equal if not greater amount of positive feedback, but those experiences are harder to recall. Just recognizing this natural human tendency is powerful in itself. It helps us understand why we’re great at inflicting pain on ourselves when we overweigh, overprocess, and generally spin on input we perceive as negative. This recognition can also help us tune into our own negative biases when considering how to deliver feedback to others, or whether or not we should risk the possible pain of seeking it out.

Here’s an example of negativity bias at work: Let’s say you received a 5 out of 5 on your performance review in June. (Again, I’m no fan of ratings or performance reviews, but they’re useful components of this example.) That 5 is supposed to be cause for celebration, isn’t it? Then why is it you left that review feeling let down? Was it the suggestion made by your manager that you could have handled that situation back in February a little better? Has your mind been churning on that comment ever since? Have you spent too many lunches complaining to your coworkers about how your manager completely missed the context of February’s situation? Did the praise you heard get forgotten? In fleeting moments of clarity, you might remember that you did receive the highest rating, that your pay increase was at the top of the band, and that your new assignment reflects the confidence your manager has in your abilities. But that negative feedback still rankles. If you’ve ever walked away from a review or any other generally positive experience with a piece of negative feedback stuck in your craw, then you need to tune in and consider that negativity bias may be impairing your ability to take in the good and accurately assess what’s been offered.

IT’S ONLY TEMPORARY

Are you an optimist or a pessimist? Do you realize it’s a choice? Interestingly, this choice plays an important role in how we engage with perceived negative input. When we hold on to the negative for too long, or even worse, forever, it limits our potential and strips us of the inner strength to move forward. In his book Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life, Martin Seligman (the father of positive psychology) warns us against making negative events “permanent, personal, or pervasive.” People who are more pessimistic are likely to hear feedback in a way that feels permanent (I’ve always been this way), pervasive (I suck at everything), and personal (Why am I the guy who always gets the negative feedback?). If we can change our listening and our thinking to be more optimistic, then we can improve our ability to hear the feedback as “temporary” (Well, I’ll do better next time), situational (That was a pretty tough environment to succeed in), and specific (Okay, this one attempt did not go well).

It’s within your power to choose.

MINDSET MATTERS

The seminal work of Dr. Carol Dweck, a Stanford psychologist, concluded that mindset matters when it comes to performance and learning. Her work, synthesized in Mindset: The New Psychology of Success,3 is an inquiry into the power of our beliefs, both conscious and unconscious, and how changing even the simplest of them can have a profound impact on nearly every aspect of our lives. A mindset, according to Dweck, is a self-perception or “self-theory” that people hold about themselves. When describing how humans approach life, challenges, and performance, Dweck coined the terms “fixed mindset” and “growth mindset.”

According to Dweck, “In a fixed mindset, people believe their basic qualities, like their intelligence or talent, are simply fixed traits. They spend their time documenting their intelligence or talent instead of developing them. They also believe that talent alone creates success—without effort.” Alternatively, “In a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment.” To bottom-line it, mindset is a key factor in influencing our potential to grow and improve.

Research has shown that individuals with a growth mindset (those who believe their talents can be developed) tend to achieve more than those with a more fixed mindset (those who believe their talents are innate gifts). Dweck’s research4 found that several factors influence this higher achievement outcome. Some of the notable behaviors are summarized in the table below:

FIXED MINDSET VS. GROWTH MINDSET

|

Fixed Mindset |

Growth Mindset |

Challenges |

Avoids challenges |

Embraces challenges |

Obstacles |

Gives up easily |

Persists in the face of setbacks |

Effort |

Sees effort as fruitless or worse |

Sees effort as a path to mastery |

Criticism |

Ignores useful negative feedback |

Seeks out feedback and learns from criticism |

Success of others |

Feels threatened by the success of others |

Finds lessons and inspiration in the success of others |

Understanding the difference between a fixed and a growth mindset is crucial to our fixing feedback movement. As you scan the comparisons between growth and fixed mindsets, it’s vividly clear why: growth-mindset people embody the behaviors needed for better feedback experiences, while those individuals with a fixed mindset do not. Here’s an idea that may seem a little less obvious: for feedback to serve as the catalyst to help us change, shift, grow, and improve, both parties, those offering and receiving, need to be operating from a growth mindset.

GETTING YOUR GROWTH MINDSET ON

As is true of nearly all things in life, mindset is not a black and white proposition. All of us have a mixture of both growth and fixed mindsets, and the blend between the two evolves over time based on our experiences. We may have a fixed view related to one dimension of ourselves (I can’t do small talk), and a growth mindset for others (I don’t know much about business strategy yet, but I’ll bet I can get up to speed on it pretty quickly). Our parsing of these self-perceptions is influenced by our life histories: what we were told by our parents, teachers, coaches, bosses, or friends, influential experiences, stereotypes we buy into, and more.

The good news is that we can shift ourselves and others from a predominantly fixed mindset to a predominantly growth mindset. However, as with the other brain shifts we’ve looked at, it takes focused effort and repetition.

TUNE IN

The important thing for those of us who want to grow and learn is to continually monitor our mindset. That requires us to tune into our inner voice. For example, when facing a new challenge, is your mind sending you fixed mindset messages? If so, evaluate your language and work toward switching it to a growth mindset, as in the following examples:

HOW WE SEE OURSELVES IN A FIXED OR GROWTH MINDSET

Fixed mindset |

Growth mindset |

I can’t do this. I’m a failure. |

I don’t know how to do this yet. |

I’ve never been good at details. |

Up until now, I haven’t been good at details. I wonder what a quick web search on “how to get good at details” might reveal. |

If I had Sara’s people skills, I could close this deal. |

I suspect some better people skills might help me close this deal. I think I’ll talk with Sara to get her advice and see what I might learn. |

I’m probably not up to this task. |

I’m not feeling up to this task right now. But let’s see how I feel after I spend a few minutes breaking the task down into subtasks. |

Once you become more consistently aware of your own fixed mindset and more skilled at switching to a growth mindset, see if you can make the same shift in the way you think about others. If you often find yourself thinking and saying things that are rooted in judgment about people’s potential, then you’re likely operating from a fixed position. When we hold fixed mindsets about others’ abilities to learn and grow, we unconsciously set limits. This may cause us to pass them over for challenging assignments that could expand their abilities and other professional learning opportunities. Here are a few examples of fixed ideas we might hold about others compared with how we might see them from more of a growth mindset:

HOW WE OR SEE OTHERS IN A FIXED GROWTH MINDSET

Fixed mindset |

Growth mindset |

Jim will never be good at this. |

Jim’s not good at this yet. But he’s learned new things before and can do it again. |

I’d have to give Mary that assignment because Jen simply couldn’t handle it. |

I’m pretty sure Mary could handle that assignment more easily than Jen. But it would be a good learning opportunity for Jen. I could offer to help get her started. |

Tom will freak out if I’m honest with him about his work on that project. |

I want to share some feedback with Tom about his work on that project. But I also need to emphasize my confidence in his ability to correct his mistakes and do better in the future. |

Whether it concerns how we view our own abilities, limitations, and potential or those of others, thoughtfully tuning in to our inner voice helps us nip those fixed mindset patterns in the bud. Once we really hear the fixed mindset messages we’re sending ourselves, we can make a habit of reshaping them into messages that spur growth instead of stunting it.

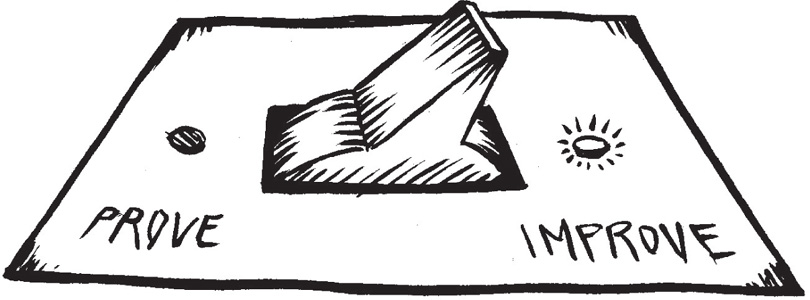

SHIFT FROM PROVE TO IMPROVE

When I painfully reflect on moments in my life when I’ve pegged the “jerk meter,” I realize it is almost always when I’m trying to prove something to someone else or myself. You know what I’m talking about, right? Those times when we’re busy being right, smart, talented, funny—whatever the aim, we’re focused on that and not on being open and tuned into the needs and perspectives of others. I wish I could tell you that behavior is in my past now that I’m at a more wise, mature, and informed stage of life (or so I tell myself), but I’d be lying to you. What I can honestly tell you is that today I’m far more aware of when I slip into “prove” mode. Not only do I know it, but I’m also better at catching it and making an intentional switch to “improve” mode. When we flip the switch from prove to improve, we shift into a growth mindset and open ourselves up for so much more opportunity.

Because we humans long for connection and validation, I believe we’ll always have to fight the tendency to pound our chests to prove our value and worthiness. That said, I trust that together we can rise above our egos and spend more of our time in improve mode. When receiving feedback, the greatest gift you can give yourself is to shift your mind into growth mode and openly consider what comes your way from the lens of how it can help you improve. Doing so saves you from performing the mental gymnastics that result from perceiving feedback as a threat to your identity. When offering feedback, we can use the idea of shifting from “prove” to “improve” to test our intent. In other words, are we extending this information to help the person improve or because we have something to prove? Switching from one to the other is an idea that can dramatically improve the quality of our feedback conversations.

PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT

Our troubled relationship with feedback has much to do with the way we humans are wired, and we have the power to change this relationship. Fear, negative leanings, and an often-distorted view of our place in the world are all part of what makes us human. But when left unexamined and unchecked, these triggers cripple our ability and willingness to pursue, offer, and accept feedback, even if it’s perceived as being positive.

Fortunately, information is power, so recognizing these tendencies allows us to work toward freeing ourselves of their hold on us. And the more we practice doing so, the better we get. Every time we observe our fear, recognize it, and choose to keep it in check during a feedback conversation, we build new pathways in our brains that gradually replace the old, suboptimal choices (e.g., defend, deflect, cave in, or run away), overwriting bad habits with good.

In scientific terms, this is called neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity is proven science that shows that we are continually shaping our brains through our everyday experiences. In simple terms, we can use our minds to change our brains. We’re creating new pathways with each experience. Neural pathways become established by repetition in much the same way that hiking trails are gradually grooved into the forest floor by many feet treading the same path.

Creating new pathways with repetition and practice is a rather simple idea, but executing it takes determination, time, and plenty of practice. Hey, I never said that creating a movement would be easy!