CHAPTER SEVEN

Selecting and Developing Project Managers

The best leader is the one who has sense enough to pick good [people] to do what he wants done, and the self-restraint to keep from meddling with them while they do it.

THEODORE ROOSEVELT, AMERICAN IDEALS

Many people become project managers by accident. The usual path to the job is through expertise in a technical specialty. In the past, those with technical skill were told to run projects calling for those skills. The best systems analysts or programmers were put in charge of software development projects, and the best engineers were put in charge of product development projects. However, the technical part of a project is often the smallest and easiest part. Technical success does not necessarily lead to project success; it is necessary but not sufficient. Upper management needs to take the lead to put into place a system that selects and develops those people with the greatest potential to manage projects. This chapter covers the processes necessary to select and develop exceptional project managers.

The Accidental Project Manager

Accidental project managers are alive and well—or at least alive; many do not feel so good about themselves or the job they are doing. Asked informally during workshops to rate their job satisfaction on a scale of 1–100 (where 100 means they are totally enthusiastic, love their job, would still do it if they were independently wealthy, and are doing exactly what they want to be doing), very few project managers rate their satisfaction as 90 or higher. A small percentage are in the 70–90 range, many say 50–70, and some say less than 50. People below 50 are in trouble; it is very difficult for them to achieve outstanding results when their enthusiasm is so low. The star performers usually rate their satisfaction as 85 or higher. People with high enthusiasm and motivation find the energy, ideas, and resources to overcome the obstacles that block their path. Research by Baker, Murphy, and Fisher (1983) indicates that the personal ambition and motivation of the project manager is the most important success driver during the formation phase of the project.

When I (Graham) taught project management for the Wharton School executive education program, it consisted initially of project scheduling techniques and explanations of available scheduling software. It was a two-day course offered in various locations across the country.

The first program was in New York City, where most participants had technical backgrounds. Most had been appointed as project manager because of their technical expertise, and most of them had never managed anything. The next program was in Texas, where most participants were from the oil business. They told the same story of how they were appointed project manager. When they were done, I remarked that it seems that most of them became a project manager “by accident.” There was general agreement with that statement.

The next program was in San Francisco, where I opened with the question “How many of you were named project manager by accident?” There was general agreement that this was so. Because I heard the same thing all across the country, the term accidental project manager was born. A number of books and articles are now available, lamenting this phenomenon.

Most organizations want project managers who come from the ranks of star performers. Technology companies typically promote people to project manager on the basis of their outstanding performance as engineers. But do these people make outstanding project managers? Will they be enthusiastic about their new responsibilities? Do they have an aptitude for the requirements imposed on them to lead and manage projects? It is imperative to recognize that the skill set of project managers is different from the skills exercised in other professional disciplines. Managers who select and develop project managers are well advised to understand the competences required from these people and adjust selection criteria accordingly.

Aptitude for Project Managing

Box 7.1 tells the story of learning a lesson about how engineers do not naturally make good project managers. A big difference occurs when training, selection, and implementation process steps are added.

BOX 7.1 Trained Project Managers Make a Difference

In the early stages of developing a new computer system architecture that was to lead HP to market prominence in the 1990s, problems were detected in the development of new products such as interface boards that were ahead of the architecture definition. A massive effort was mounted to design a process to resolve these issues, drawing on a large group of technical experts from several divisions and multiple projects. Engineers were formed into study groups to investigate and propose solutions. Because architecture decisions are far reaching, the process had to include thorough reviews from all projects developing products. Resolution of issues also had to take differing organization priorities into account.

The first phase reached resolution seven weeks beyond a nine-week schedule. Too much time spent by too many people on a process that had many inefficiencies made management nervous. A retrospective analysis at that point highlighted the role of study group chairs who were lead engineers as an important area for improvement. A typical report at the weekly control group meeting was “We’re still working on the problem and need more time.” They maintained a low profile and did not ask for help. It turns out that these people had no training on project management; they were trying to approach problems with strictly technical solutions. The real problems, however, were not technical: there were two or three possible technical solutions, and each organization favored a different one. The problems were organizational: no clear decision-making processes or ways to assess impact when operating across organizations were evident.

For subsequent issue resolution phases, trained project managers were assigned as study group leaders. They did not need a great depth of knowledge in computer architecture. Their role was not to argue for a position but to concentrate on an effective and efficient process for bringing technical experts into consensus. When tough issues could not be decided, they were passed up to the control group and eventually assigned to functional managers who would make a business decision. Better estimation, scheduling, and communication techniques were also applied. Selecting leaders from people committed to exercising project management practices resulted in a shorter schedule met to the very day using fewer technical experts.

It would seem that the first requirement of a potential project manager is the desire to be one, including the desire to be a manager in general. It makes sense that the people who are selected and developed to do a particular job should really want that job. A colleague once described newly hired HP employees as “brilliant adolescents.” The company hires the best people it can, usually from the top ranks of technical graduates. And indeed, they have all the energy and enthusiasm of adolescents, applying themselves to many new opportunities, putting in long hours, going from one task to another with minimal guidance and even less formal training, and moving from project to project. Most learning is on the job. They enjoy the excitement of exploring new technologies. They know from the “next bench” that other engineers also love the esoteric products they develop. All that talent in a seemingly disjointed environment is the reason that some amazing products finally get released to the market.

MANAGEMENT TALENT

But management talent is not always obvious. The glamour of 25 percent yearly growth by high-tech companies in the 1970s and 1980s was evident in the youthful cadre of managers. Promotions came early for them, often before they developed much in the way of people skills. Project managers counted on their technical knowledge to make decisions, not on their ability to influence or motivate people.

Unfortunately, retaining an adolescent mentality in a growing organization is like carrying around a time bomb; it eventually explodes. The problem is exacerbated in difficult times, when stress levels run high. After a while, long working hours take their toll. Call it burnout. Disappointment sets in when customers do not purchase products according to optimistic forecasts. Projects are canceled after project teams expend dedicated effort on them for six months or a year or longer. The fast track up the management chain is very narrow or nonexistent. People are redeployed, as happened during the late 1980s, and must search around their company for other departments that need them. This was not supposed to happen to technical professionals, but it did. It happened again in the twenty-first century, with dot-bomb collapses and terrorist attacks. Violation of basic business fundamentals and loss of confidence in the economy put many people out of jobs.

And so, the adolescents grew up. The realities of highly competitive markets require maturity, and maturity means that people do not fight the same fire over and over; they learn from past mistakes. Market “misses” cannot be covered by charging a premium for top-of-the-line products, so mature people learn to fix the process, not the product. An opportunistic approach to launching projects still appears chaotic, but it features an overarching strategy as well as criteria for making decisions. Project managers prove their efficacy when ambitious projects produce delightful products, meet schedules imposed by tight market windows, and use a lean staff of dedicated professionals. At the helm are leaders who have an aptitude for producing results by working with people because they are trained in the practices of project management. It also means that organizations need skilled managers who get the right work done with fewer people.

In light of all this, appointing accidental project managers is no longer appropriate, if it ever was. Upper management needs to insist on and assist in the development of a process that selects and develops individuals with the best aptitude to become successful project managers.

A participant in a master’s program on project management stated,

Regarding the hiring process of a new PM, which often is not discussed, but it really is a huge part of building a successful team. I think especially so in technical projects, smart choosing of a PM is critical. They should be picked based more on skill rather than reward. Of course, one common dilemma in technical industries that I have encountered at a past job was that all project managers were really just technical engineers promoted to the managerial level. So, they certainly had the technical experience, but the organization did not make many efforts to train them in PM aspects. This caused many challenges, since many were lacking communication, leadership, or planning skills required for a successful project implementation.

I think the problem of insufficient resources is a fairly common one, and something that I am familiar with. It can pose quite an issue when people are all stretched too thin and no one is really capable of doing a quality job or keeping up with the workload.

ENGINEER’S DISEASE

The idea of “engineer’s disease” developed while I (Graham) was talking with a crew of project managers. I was talking about Legionnaires’ disease, and they thought I said “engineer’s disease.” They quickly began to discuss the signs of such a malady, such as “a permanent ink stain all over your chest,” “a pocket protector full of pens,” or “eye problems due to narrow vision.” It was amazing how fast the group could construct a list of negative attributes for people who suffer from this imagined disease.

A few weeks later I was talking with a different group of project managers and said, “Suppose someone on your team has engineer’s disease,” not having told them how the term originated. No matter, as they quickly enumerated the problems that engineer’s disease would cause, like “I’d guess we’ll have to hire an interpreter.” I exclaimed to the group, “You don’t even know what engineer’s disease is,” but they said, “Yes, we do.”

I continued to use that term to help project managers understand that we all have images of people from other departments in the organization. Of course, there will be people from other departments on the project team. The project manager and the project sponsor need to eliminate these negative images. I suggest doing this by having each team member tell other team members what he or she is going to contribute to the final product. This is best done during the first or second meeting so that all team members will be seen as valuable contributors to the final product, even if they do have “engineer’s disease.”

The Need for Alternate Career Ladders

Managing is not engineering. According to one project manager, “Someone once told me that management was a lot like engineering, except that you solve problems with people. Sure. And bow hunting for grizzly bear is just like target practice, except it involves real animals. The analogy entirely misses the raw adventure of the real thing.” He added: “A manager’s accomplishments are measured differently than an engineer’s.… I was creating an environment that allowed the engineers to succeed. When the engineers were successful, I was successful” (quoted in Platt, 1996). Another project manager once remarked, “Project management is too important to be left to amateurs.”

The first important criterion for project manager success is the desire to be a manager in general and a project manager in particular. Many organizations, however, force people into the position of project manager even if they are not adept at it and do not desire to become one. True, the project management position may be the only way to promotion beyond the job of technical specialist; the step from technical specialist to project manager may be the assumed progression when there is no way to move up a technical ladder. It is far better, however, if alternative upward paths exist: one through technical managership and one through project managership.

With dual promotional ladders, technical managers can stay in their departments and become core team members responsible for the technical portions of projects. They have many skills and interests, and they will work on project teams that include a variety of departments. They have to be able to see the whole picture, not just have a view of their own specialty. Dual ladders also allow progression through project management. Project managers need to be able to manage technical specialists while handling the behavioral and administrative tasks that motivate the specialists to do their best work. What path they take depends on motivation and the trust they can engender from others.

Project Manager Selection Criteria

Changing the project manager selection and development criteria is critical to the maturation process. Fortunately, studies and research are starting to identify the competences needed by project managers. An effective project manager is more than a brilliant engineer; research indicates that technical knowledge is not paramount to being a successful project manager even in a technical organization.

Research, plus personal experiences, point to the enthusiasm of the project manager as a key criterion for project success: the project manager not only must want to be a project manager but also must want to manage the project in question. Thus, part of the selection process, beyond finding people with the aptitude to be project managers, is matching them with projects that they are interested in managing.

David Packard (1995), a cofounder of HP, stated as part of the corporate objectives in 1961: “A high degree of enthusiasm must be encouraged at all levels; especially the people in important management positions must not only be enthusiastic themselves, they must be selected so they will engender this enthusiasm among their associates. There can be no place, especially among the people charged with management responsibility, for half-hearted interest or half-hearted effort” (p. 126).

One definition (Wheelwright and Hayes, 1994) says that an effective project manager is a “technological entrepreneur” who can do each of the following:

• Invoke the inner confidence to ask dumb questions and keep asking them, plowing through the jargon, implicit assumptions, and unstated relationships that often surround technology

• Thrive in the ambiguity that surrounds working in an unstructured environment without clear lines of authority or specific resources

• Operate through interpersonal ad hoc agreements and understandings, on the basis of personal credibility, goodwill, and mutual advantage rather than relying on organizational loyalty or rank in that organization

• React instinctively to opportunities and crises, and thus maintain the credibility of the project and keep it progressing inch by inch, rather than waiting for … (fill in any excuse)

• Identify the people whose support is crucial to the success of the project and win their allegiance

A keynote paper presented at the World Congress of Project Management (Gadeken, 1994) identified from research six competences that distinguish outstanding project managers from their contemporaries:

• Sense of ownership and mission. Sees self as responsible for the project; articulates problems or issues from broader organizational or mission perspective

• Political awareness. Knows who influential players are, what they want, and how best to work with them

• Relationship development. Spends time and energy getting to know project sponsors, users, and contractors

• Strategic influence. Builds coalitions and orchestrates situations to overcome obstacles and obtain support

• Interpersonal assessment. Identifies specific interests, motivations, strengths, and weaknesses of others

• Action orientation. Reacts to problems energetically and with a sense of urgency

These competences fall almost exclusively within the category of managing the external environment, which means managing relationships outside the project office.

To support the emphasis on managing the external environment, the same study compared importance rankings of the project manager competences with those of other professional specialties (Gadeken, 1994). Other professionals considered technical expertise (ranked 1 by them, 21 by the project managers), attention to detail (7 versus 22), and creativity (3 versus 15) as far more important than did the successful project managers. Key areas that project managers ranked higher than other professionals were sense of ownership and mission (ranked 1 by the project managers, 17 by other professionals), political awareness (4 versus 21), and strategic influence (14 versus 23).

These data support the idea that technical expertise is not the most important requirement for successful project management. The project managers ranked this aspect 21st out of 27 (it does show why technical expertise was so long considered the most important: other professionals rank it number 1). Clearly, the practice of promoting the best engineers to manage engineering projects was ill founded. This study indicates that a sense of mission, the sense of really wanting the project to succeed, and a political awareness of how to get things done are far more important. Technical expertise is necessary on the core team, but not necessarily by the project manager.

Gadeken (1994) goes on to say that “the transition from functional specialist to project manager may be conceptually quite difficult, mainly because project managers need external interface skills to a much greater extent than their counterparts in operational commands.”

One of Gadeken’s (1994) recommendations is especially striking: “The preferred alternative for project manager selection is to assess which candidates have or can more readily develop the critical leadership and management competencies. Training can then be provided or tailored in project management functional disciplines (knowledge areas) to augment the candidates’ prior knowledge and experience base.” We usually do it the other way around.

Another firm did a competency analysis to define a project manager (PM) model (Sarna, 1994). Results from surveys and focus groups were validated by firsthand observations and ratified by managers of project managers. Even before entering individual development planning and training strategies, project management candidates must fit this firm’s PM Competency Model by showing proficiency in the following areas:

• Business development

• Client relations management

• Communications skills

• Finance

• Monitoring and reporting

• Personal self-development

• Planning

• Problem detection and resolution

• Staff development

• Staff management

• Quality management

• Organizational utilization and support

Candidates with this profile are then eligible for training and development in curricula covering methodology, planning and control, client relations, project administration, staff management, and integrating workshops.

Keane Consultants employed a behavioral research firm to identify the key project management qualities that make the difference between average and superior performance (Edgemon, 1995). From this it developed the Project Manager Competency Model, which has four clusters:

• The problem-solving cluster, which includes competence in diagnostic thinking, systemic thinking, conceptual thinking, and information gathering

• The managerial identity cluster, which includes competence in strong project manager identity, self-confidence, and flexibility

• The achievement cluster, which consists of concern for achievement, results orientation, initiative, and business orientation

• The influence cluster, which stresses the importance of organizational and interpersonal astuteness, skill in the use of influence strategies, and team building, along with a client orientation and self-control

Continual studies on project manager competency sponsored by the Project Management Institute (www.pmi.org) largely support the diversity of skills needed for this profession. One focus on membership study (“Survey Reveals,” 2001) points out that the greatest challenge to the future of project management is public perception and acceptance of the profession and acceptance by top management. The top capabilities needed from project leaders are leadership skills such as vision and motivating others, people skills and getting along with others, and management skills for directing and managing others.

David Frame (2007b) used the guidelines he helped develop for the Project Management Institute to define the most important competencies for individuals, teams, and organizations. He concludes, “Higher levels of management should do everything possible to create an environment that enables their employees to shine. The key word here is support.… Moral support means that management creates a culture that encourages employees to excel in their tasks. High performance is encouraged and slacking of is seen as unattractive. One way to create a healthy environment is to empower employees to make a wide array of decisions. By being part of the decision-making process, employees incur an obligation to perform their tasks effectively. This is the essence of ownership” (p. 214). His list of essential project manager competencies is shown in Figure D.5 in Appendix D.

Reward based on performance and promote based on ability, advise Hammer and Champy (1993, p. 74): “Advancement to another job within the organization is a function of ability, not performance. It is a change, not a reward.” Managing is a particular skill. Too often people are promoted to project management as a reward for past performance; these are accidental project managers. Changing to a project management organization means assessing the potential of a candidate to perform the project management role based on competence in the skills that job requires. Often these candidates will not have distinguished themselves as individual contributors or in technical roles, because these are not their greatest skills. But put them in project management and they shine!

Belbin’s research (1996) on successful management teams singled out effective leaders as those who are trusting, accept people as they are, have a strong and morally based commitment to external goals and objectives, are calm and unflappable in the face of controversy, are geared toward practical realism, possess basic self-discipline, are naturally enthusiastic, and have a capacity to motivate others while being prone to detachment and distance in social relations. The successful team leader is tolerant enough to always listen to others but strong enough to reject their advice. Such individuals show approval of people who accomplish their goals, like people who are lively and dynamic, know how to use resources, never lose their grip on a situation, and reach their own judgments. They are adept at drawing out the potential of the group and get high marks on skill in consultation, delegation of work, and firmness of decisions. Belbin reports that leaders of project teams appointed on the basis of this profile rather than on the basis of experience and seniority achieve more favorable outcomes and the most reliable results. Belbin, who observed these leaders play an important part in teams that encountered the usual difficulties but overcame them to finish strong, also cautions: “It is quite difficult to identify individuals with this gift for it belongs to some deceptively ordinary people.”

Technical ability is not an overriding indicator of the effective project manager. It certainly provides increased credibility on the job in a high-technology environment but has been elevated in importance beyond what it deserves.

Project managers need to have leadership potential. Some do have this potential; others are followers. A manager who is a follower simply takes the assignment from upper management and passes it along to the team. A leader develops a personal vision about the assignment that includes a vivid description of the significance or the value-added contribution to be made by the team. These leaders are able to inspire team members to share the vision and get excited by it.

An upper manager who successfully brought complex programs to completion shared that effective project managers need three things: vision, focus, and resources. If they have those, they possess immense power to get things done, and unfortunately may therefore be perceived as threatening by other managers. Organizations may respond by not giving such people control of the resources they need and requiring that they manage multiple projects. What they cannot take away, however, is personal vision. Project managers need to cultivate a personal vision of a desired future state associated with project success. The ability to create motivating visions is perhaps their most powerful project management tool.

Pulse of the Profession Findings

The Project Management Institute regularly conducts research and publishes it in an annual report titled Pulse of the Profession. One insight from the 2018 report states: “Project professionals will broaden their skills and learn in new ways” (PMI 2018b, p. 12). Research reinforced that the role of the project manager is expanding to:

• Strategic adviser: plans, executes, and delivers

• Innovator: acts as product owner and developer

• Communicator: is always clear and concise—no matter the audience

• Big thinker: is adaptable, flexible, and emotionally intelligent

• Versatile manager: has experience with all approaches—waterfall, Scrum, Agile, lean, design thinking

The report elaborates: “How project professionals prefer to acquire those skills will also change. Demand is increasing for faster, more flexible, and easier-to-learn project management methodologies and approaches. The constantly-changing technical landscape—from social media, to web-based tools, to learning management systems— will present tremendous opportunities for exploration and experimentation. The shift toward on-demand, customized, and problem-specific learning will grow. Innovations in learning will continue to make it possible for the new worker to learn anything, anytime, and anywhere” (p. 12).

Another insight from the report states: “Organizations will rely on their project professionals to take advantage of disruption—not just react to it.… Failure to acquire, train, and retain project managers can have catastrophic consequences. Research tells us that skilled, trained, and experienced project managers increase the likelihood of project success, meeting original goals, and delivering on business intent. As the value of project management to an organization’s ability to implement strategy becomes more apparent, project managers will increasingly serve in more high-profile and strategic roles and will be even better positioned to usher their organization through the impending disruption” (p. 13).

As organizations navigate new frontiers,

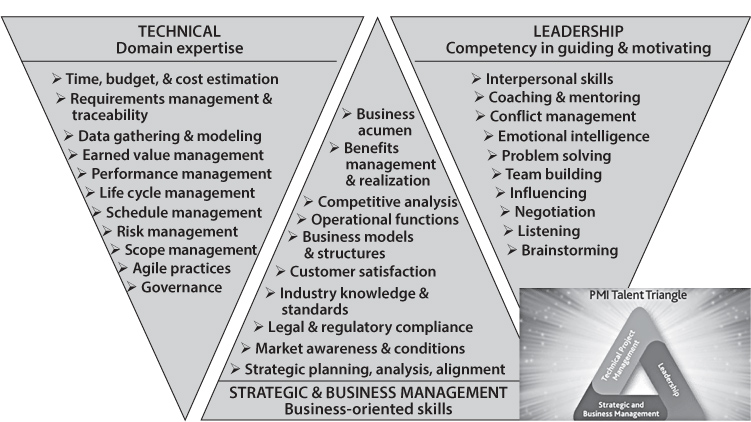

success in this new environment requires combining traditional project management skills with an understanding of today’s marketplace, a deep knowledge of the organization’s products and services, and how those products and services are being used by customers. We have long advocated for a blend of technical skills, leadership skills, and strategic and business management skills—as outlined in the PMI Talent Triangle®.

While technical skills are core to project and program management, PMI research tells us they’re not enough in today’s disruptive environment. Companies are seeking added skills in leadership and business intelligence— competencies that can support longer-range strategic objectives that contribute to value delivery. We recognize that these skills include an understanding of the impact of evolving technology on both major internal change projects and external customer deliverables. (p. 15)

Figure 7.1 articulates skills in each area of the talent triangle.

Top Five Criteria for Competent Project Managers

The results of research and experience so far seem to point to five characteristics possessed by people who make successful project managers.

They Have Enthusiasm. The most important criterion is the desire to do the job. This means that the person knows what the job entails or is willing to learn and wants not only to be a manager in general but to be a manager in a project environment and on specific projects. Make determining the level of enthusiasm part of the interview and selection process. Potential project managers can take a transitions course to ensure that this job is what they want to do. If the enthusiasm and aptitude are there, they can be trained in the skills of the job.

They Have High Tolerance for Ambiguity. Project managers need to be ready to work with very ambiguous authority. People who need clear-cut authority do not do well as project managers. They often need to be ready to work in situations where absolute authority is nonexistent, roles and responsibilities are uncertain, and measures of success depend on customers who constantly reevaluate their expectations. They also need to be comfortable with the ambiguity that exists at the beginning of a project and possess the ability to turn that ambiguity into concrete deliverables. They can seek out opportunities in ambiguities.

They Possess High Coalition and Team-Building Skills. The project manager needs considerable skill in building coalitions of external stakeholders and teams of internal members and in translating the vision of the project to all. The power to get a job done is granted by external stakeholders, and the ability to get the job done lies mainly in the project team. Project success depends heavily on the project manager’s ability to build coalitions and teams, thereby earning legitimacy. This often involves being more proactive than reactive, as well as moving people from divergent to convergent thinking.

They Have Client-Customer Orientation. Although coalitions and teams make it possible for projects to get done, the final measure of success is the satisfaction of customers. Customer expectations and problems continually change, so the better the project manager understands the customer situation, the better the chance that the final product will solve customer problems. The project manager must be able to take customer needs and craft them into a vision that can be used to motivate and direct members of the project team.

They Have a Business Orientation. According to Collins and Porras (2004), an inclination toward business is a highly important factor in building a sustainable and visionary business. Project managers need to understand the business of the organization; they will make many decisions that will affect many parts of the organization, so they need to know the effects of those decisions. In addition, they will make decisions affecting the final profitability of the final product, so they need to understand how the organization makes and maintains a profit. Business orientation will determine the final success of the project. The project needs to meet strategic objectives of the organization, help the final customers and end users solve their problems, and make a profit.

Englund and Bucero (2019) expand on project management competencies in the context of becoming more complete by expanding skill sets and drawing on multiple disciplines. A summary of these skills is depicted as an organic molecule in Figure D.3 in the Appendix D.

A Project Manager Selection Process

How do you find good potential project managers? The first step is to know what you are looking for by using the criteria just outlined. The next step is to use a critical behavior interview process where candidates are asked what they would do in given situations. Situation-based tests might also be used to get similar results. For both, the responses are best evaluated by successful project managers. Of course, people do not always do what they say they would do, so an extra validation would be to watch the results of experiential exercises and behavioral simulations.

A recent graduate was interviewing for various positions but disappointed that more experienced candidates were selected. Persevering, he got a call one day from a director of engineering. He noticed the interviewer’s questions were directed more toward learning about his critical thinking, his approach toward working with people in different time zones, his collaborative attitude, and his personality—not toward the technical spectrum. The interviewer concluded by saying, “Technology comes and goes; the technical skills we acquire are just temporary, and they become obsolete sooner or later. But who we are, how we behave in a team environment, and what we do for the team are the most important qualities an individual can have. Technical skills are complementary to the position, and they can be acquired through training, no big deal.”

Few candidates will be proficient in all five of the top criteria for competent project managers. But remember that the key is to discover the candidate’s potential. Successful candidates may then be assisted in putting together a development plan. However, potential is very difficult to ascertain and to judge. It might help to ask the candidates what obstacles they overcame to get where they are and how they did so. Their responses would give some indication of enthusiasm and tolerance for ambiguity.

Having a process for project manager selection is very important. In one highly effective interviewing process, an open requisition is posted on the electronic notice board. The hiring manager interviews respondents by phone and (based on a set of questions prepared in advance or simply on visceral reactions) selects a few for in-person interviews. Peers and team members who will work with the winning candidate conduct the interviews; the candidate who receives the job offer must not only be competent for the position but also fit in with the group or provide talents that do not currently exist within it.

Each interview avoids duplication of effort by covering different ground. Each interviewer is assigned specific job areas to cover, such as teamwork, goal setting, conflict resolution, work style, and technical proficiency. This process is inherently more inferesting to candidates, as they do not answer the same questions repeatedly. Because team members who do the interviewing are involved in the process, they take more accountability for the decision. The group also appears much better organized to the interviewee.

Each interviewer fills out an evaluation form after the interview, and all meet to discuss their perceptions. These discussions provide a forum to bring to the surface subtle feelings that one person may be hesitant to write down or bring up alone. When such a concern is shared, someone else may recall the same or another area of concern. The group decides if the concern is relevant and important. Further research may be needed; the candidate may be interviewed further, or associates of the candidate may be interviewed. There must be a consensus decision for an offer to be made. Sometimes the final set of candidates is so compelling that a process similar to prioritizing a project portfolio is followed (see Chapter Two).

This process consumes a lot of time and may involve people in discussions that make them uncomfortable, but it greatly reduces the risk of bringing in someone who will not be a good fit. No person alone could detect all the positive or negative qualities of the candidates, but group discussion makes it clear whether one candidate stands out. If no such candidate stands out, a gap in the credentials of an otherwise excellent candidate may be bridged by training or by reassigning responsibility for a function to somebody else. The group may choose to pick the best from the group of candidates or to keep looking.

As the project management profession has advanced and more people are entering the profession, additional avenues for selection become available. Consulting firms and contract workers may fulfill part-time project management positions. A key element remains to find a person that fits within the organizational culture. A fine line exists to ensure that contractors are not perceived as taking away a potential job from an established employee within the organization.

Project Manager in a Minute is an exercise that I (Graham) developed to help teach new project managers that the conflicting goals of project stakeholders will be a problem as they attempt to manage the project. It begins by selecting a new project manager from the audience and getting four people to represent four stakeholders. One person plays the project accountant, who wants to stay within budget. To achieve this, the accountant wants fewer features in the final product because more features costs more money. So, the accountant’s role is to say to the project manager “fewer features.” The person who represents the systems area asks for “more time.” The person who represents the finance department wants the final product to have a “high price” in order to make more money. The fourth person represents the customer. Of course, the customer wants “more features,” in “less time,” and at a “low price.”

The four stakeholders stand in a square with the project manager placed in the middle. The stakeholders continually yell out what they want while the project manager is spun around and around by the shoulders. It often gets quite loud, and the project manager usually ends up dazed and confused. At the end, I ask the project manager which stakeholder he or she heard the best. It is never the customer.

This one-minute exercise represents a “Welcome to the world of project management.” It helps potential project managers realize that they are being painted as a target.

Transition to Project Manager

The project management initiative at HP assisted the selection process by offering a course to potential project managers called Transitions to Project Management. The course explains to candidates what project management requires of the individual, how being a project manager differs from being a project contributor, and how the ability to lead projects can be developed.

In this one-day course, participants learn the many elements of managing and leading projects. The intention is to develop awareness of the differences between individual contributors and project managers. The course explores the transition from individual contributor to the roles and responsibilities of project management in environments where flattened work groups predominate, with fewer management positions and increased number of direct reports.

It also identifies key attributes of successful project managers and provides a forum for participants to discuss best practices with successful project managers from their site. It does not explain how to define, plan, or manage projects; these are covered in another course on project management fundamentals. It is, however, designed for people from all functional areas and may benefit current individual contributors who are taking on more responsibilities, as well as new or aspiring project managers or leaders.

The objective of such a course is for participants to learn to do the following:

• Identify key issues new managers face when making the transition from individual contributor to project manager

• Identify and discuss new personal perspectives and realizations about project management

• Refer to a participant guide to identify available on-site management workshops, courses, and consulting that can strengthen management skills and project team functioning

Course delivery is classroom based and features guest project manager presentations and stories, facilitated interaction, case studies, questions and answers, and discussion. Announcements of course dates are sent out periodically by internal email.

The comments of course participants are generally positive (for another experience, see Box 7.2):

“This course has caused me to think about which career path I really want to pursue: project management or technical contributor.”

“I highly value the opportunity we have in the course to hear from successful project managers.”

“I never really appreciated the scope of project leading and how difficult it can be.”

“I really resonate with the job of the project manager. It’s definitely what I want to do.”

After taking the course, some people decide they do not want to be project managers. This is a positive response; the alternative may be promotion to project manager, a year or two of hell for everyone involved, and an eventual return to the role of individual contributor. Much more productive is preventing that scenario. This also indicates again the importance of the dual career path; the technical career path offers an alternative to the management path, which is preferable for those who do not want to be project managers. It also helps organizations not lose the technical contributions these people make. If a dual path is unavailable, these people may elect to leave the organization; or they may stay and become ineffective project managers.

Another testimonial came from one site where interviews were conducted for a project manager position. Interviewers commented that the quality of persons applying for the position and the interview discussions were much more impressive because the interviewees had attended the transitions course.

I (Graham) remember well my own version of the transition course. I had received my degree in systems analysis and was running a small computer center at the time. The next step would have been to run larger computer centers in larger and larger organizations. To check out the possibilities, I went to a conference of computer center directors in St. Louis. There I learned just how much management was involved, how extensive were the politics involved, and how much emphasis was put on installing and maintaining ever-larger computer systems. The knowledge made me physically ill, which I interpreted as a sure sign that I did not want such a job. It gave me the impetus to complete my doctorate, go to the University of Pennsylvania, and get a job that I absolutely wanted. My “transitions course” saved me and many others a lot of grief.

During occasional presentations at the course, I (Englund) shared my belief that project managers should have an aptitude for managing projects. My career included doing service calls as a field service engineer on medical equipment. Later, as a sales development engineer, I responded to calls from the field about sales opportunities for computer systems. Each day brought new problems to solve, but I was in a reactive mode. My performance was adequate but not outstanding; I needed something different. As far back as I can remember, I am most alive when doing projects—functioning in a proactive role.

I try to explain aptitude by describing what I am doing when I feel I am making a significant contribution. Although I was trained as an engineer, I am not happy digging deep into technical complexities or doing maintenance tasks. People make things happen. To me, a good day at work includes helping a team of experts solve organizational problems. Behavioral issues affect organizational effectiveness far more than technical problems. My contribution may be to refocus efforts on the real problem, remove obstacles, or design a process. I need to identify important challenges, prepare a plan, adapt and execute that plan, and produce concrete results. Then I look around for a larger project to tackle.

Managers of project managers need to search for people with this aptitude wherever they exist in the organization, for these are the ones who should be in charge of projects. Availability alone is not a skill set.

A Project Manager Development Process

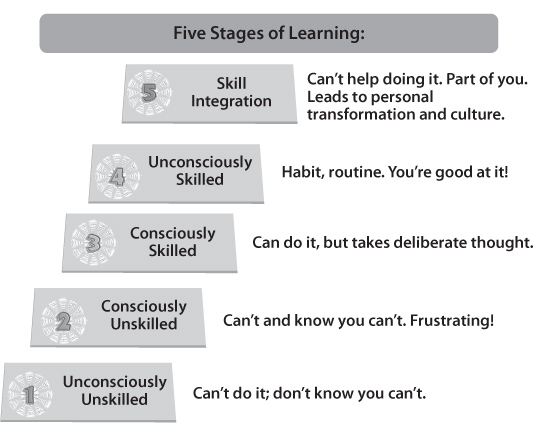

Project manager development follows the basic model outlined in Figure 7.2. At stage 1, a person is unconsciously unskilled and does not even know there is such a thing as project management. One day, however, this individual is appointed (perhaps accidentally) as a project manager and is abruptly at stage 2: the person now knows that project management exists but does not have the ability to do the job and knows that too. This consciously unskilled person, with any luck, is able to begin a development plan by taking some courses and applying the lessons learned to the job. Now the individual is at stage 3, consciously skilled, applying the learning but with deliberate effort.

FIGURE 7.2 The Progression Path of Development as a Project Manager

Developing truly seasoned project managers takes much development effort, but unfortunately, many development efforts stop at this point. People at stage 3 need to move beyond deliberate effort into habit, perhaps by taking on larger projects and talking over problems and experiences with a mentor. They work at becoming stage 4 project managers, who are unconsciously skilled and carry out best practices through habit. The final step is skill integration, where best practices are integrated into their complete work life. Stage 5 is best reached by discussing experiences with peers and by teaching others, becoming part of a network of project managers; attending and presenting papers at company and external conferences; attending best practice forums; seeking outside certification; and becoming a project mentor.

All the following may be components of a good development plan for project managers:

• Taking courses for skill development

• Entering a mentor program

• Becoming part of a network through email connections, company conferences, outside conferences, and the web

• Attending forums on specific practices and gaining the ability to share best practices

• Obtaining certification from the Project Management Institute, which helps the individual and is becoming a standard for experienced project managers (a number of universities also offer graduate project management certification programs)

Additionally, organizational awareness is the ability to read the currents of emotions and political realities in groups. It is a competence vital to the behind-the-scenes networking and coalition building that allows individuals to wield influence, no matter what their professional role. Unlike IQ, emotional quotient, or EQ, may be developed. Various tools and assessments are available, as well as using small group discussions to share best practices and recommendations for improvement. See Figure D.6 in Appendix D for a grid depicting “what I see” and “what I do.” The Complete Project Manager’s Toolkit includes an assessment tool set (Englund and Bucero, 2019).

COURSES FOR SKILL DEVELOPMENT

Most project management development curricula cover the following five topics for skill development:

• Project techniques. Normally a project management fundamentals course teaches basic project planning, estimating, and risk analysis techniques. When participants finish this course, they know how to put together a project plan.

• Behavioral aspects of project management. This course covers such areas as team building, motivating team members, developing effective project teams, and dealing with upper managers, contributing department managers, and other stakeholders.

• Organizational issues. This course covers techniques for managing across organizations when the project manager has all the responsibility and little authority. It teaches participants how to get projects done in spite of the rest of the organization.

• Business fundamentals. Many project managers have a technical background but lack basic business knowledge. This course teaches the business of the organization, how decisions affect the bottom line, and how to run a project as if it were a business. David Packard (1995, p. 44) says he learned much about running a business from courses outside his engineering major: “I gained a lot from two classes I took at Stanford: business law and management accounting. I had signed up because I thought they might be of some use in our new business. Looking back, they were among the most important courses I ever took.” To have project managers think about projects as a business, business fundamentals courses are important.

• Marketing and customer issues. In the end, there needs to be a market and a set of customers for the final product of the project. This is true even of internal projects. This course focuses on the techniques of defining and developing a market, as well as understanding the needs and desires of the project’s customers and end users.

A PROJECT MANAGER MENTOR PROGRAM

In The Odyssey, when Odysseus, king of Ithaca, goes off to fight the Trojan Wars, he leaves behind his trusted friend Mentor to look after his son, Telemachus. The word mentor—meaning a wise and trusted friend—has been part of the vocabulary of relationships ever since. A mentoring relationship involves seeking or giving advice to help the mentee—the person being mentored—grow, develop specific competences, and tap the experiences of others. New project managers often find themselves in highly stressful situations as they try to make the transition from technical contributor to team leader. Many successful project managers say that this was the most difficult time in their careers. A newly appointed project manager may encounter informal mentoring spontaneously or through luck; historically, this was a primary means for learning from those who had gone before. A more formal program strengthens the mentoring process by guiding and supporting volunteers who want to improve their mentoring relationships and increase the benefits they give and receive.

Facilitated mentoring can be defined as a structure and series of processes designed to create effective mentoring relationships, guide the desired behavior change of those involved, and evaluate results for the mentees, the mentors, and the organization. The reason to begin a mentoring program for project managers is to reap the advantages of a sustained one-on-one support activity. A mentoring program improves the performance of persons responsible for managing projects and increases the opportunities for cross-organizational networking.

A mentor’s role is to provide guidance or advice, or both, but does not substitute for or replace the management role. There is a distinct difference between mentoring and managing: a mentor does not sit in judgment on a mentee and is not involved in performance appraisals of the mentee. Ideally, the mentor is in another organization and has no direct impact on the mentee’s job position. Mentors can give advice from their perspective, but the mentees must ultimately judge the value of this counsel for their particular environment and have the option to take it or leave it. A good mentoring program has advantages for both parties:

Benefits for the Mentor

• The chance to help someone acquire skills

• An opportunity to help someone achieve results

• Self-esteem enhancement

• Job enrichment

Benefits for the Mentee

• Higher performance and productivity ratings

• More pleasure in work and greater career satisfaction

• More knowledge of the technical and organizational aspects of the business

• Unbiased advice to solve specific problems

• Access to impartial perspective on issues

A successful mentoring program has these ingredients:

• People who volunteer to be mentors and to describe their areas of expertise

• Potential mentees who ask to be mentored and are willing to identify their coaching requirements

• Mentees calling mentors to establish a relationship

• Conversations that are positive experiences for both parties

• A central organization that facilitates connections and monitors results

• Complete confidentiality between both parties

Not all mentor programs need be as formal as described here. Upper managers can encourage informal contact and exchange between new and veteran project managers, and individual project managers should seek out mentors.

ELEMENTS OF A PROJECT MANAGER NETWORK

In addition to learning basic skills in class and from a mentor, project managers continue to develop by networking with each other. This network can take on several forms:

Email connections, where every project manager is connected to every other project manager through an email folder. A project manager who has a question or wants to know if others have experienced a similar problem can ask others in the network.

Company conferences, where all project managers in the organization can get together in person to discuss mutual problems of project management. (See Chapter Nine for a full discussion of how this was done at HP.)

Outside conferences, such as those of the Project Management Institute (PMI) and the Product Development and Management Association, give project managers a chance to meet and listen to others in the same profession. Society membership is also an important source of information.

The internet and the web, which provide additional opportunities for interaction.

Case Study

This story describes a project manager development opportunity, how it was structured for maximum learning, and how failure to get complete closure after the project affected the motivation of its participants.

A professional association sponsored a major event that involved the participation of all chapters within the region. The planning of the event followed most steps required in the project management process: a vision was created and agreed upon; speakers who were known to have a valid and compelling message that fit with the event’s established theme were invited; sponsors were signed up; the event was well publicized, with promotional email materials citing key messages that would be covered; and weekly status meetings with all project participants were held. Key documents were posted and available to all on a SharePoint website. The project manager drafted a “day in the life of” scenario that allowed planners to step through all details of the project to ensure all tasks were complete. Enthusiasm was high, response was equally high, the event happened as planned with attendance at maximum capacity for the site, and financial returns for the association were bountiful.

I (Englund) was the content and program director for the event. Drawing from previous experiences where calls for papers from unfamiliar contributors provided marginal to negative results, I was able to influence the up-front design of this project. I designed a single track so that all participants heard all messages, and I invited known speakers with proven messages instead of putting out a call for papers.

While the event provided maximum learning for all involved, the problem came after the event concluded. As volunteers who put much time into this project, we wanted to ensure that the reasons for our project’s success were clear, establish that we had met all our goals, and know that our work was recognized. Surveys of attendee reactions were conducted, but the results were not shared among the team. The final numbers from accounting were known to only a few. A set of resourceful and productive volunteers was assembled but then dispersed. Lessons learned or best practices applied were not captured. Subsequent events did not replicate key factors that made this event so uniquely successful, and those later events did not generate the same level of participation as this event.

I was not able to get the project manager and sponsoring organization to schedule a follow-on project review. We all got busy after the event, and a review date was missing from our original plan, so it never happened. The result was that some individuals felt this was an incomplete experience, that all the hard work was for naught.

People want closure, especially after a successful project. We learned from each other and had fun together, but I sensed that this event was not regarded with the same level of high regard that I felt about it, simply because there was no forum for sharing those feelings. It seems like no news is bad news. I believe we “stretched the rubber band” about how to conduct an event like this, but the organization snapped back to how it always operates. We lost the opportunity to make a longer-term impact in our community and build on messages generated by the event.

As a project team member, I was accountable for our not achieving the desired closure. I also realized how dependent we were on the project manager to guide us through this stage. We needed someone to urge us to complete unfinished tasks. Since that did not happen, we were left with unexplored feelings.

This experience underscores how influential a project leader is with regard to all aspects of projects, from beginning to end. If the ending—meaning the cathartic process of debriefing what went well, what we should do again, and what we should revise— is not complete, people will be less motivated to apply their best efforts to future work. Because people’s attention during the closing stages naturally shifts to the next activity, it is imperative for the project manager and the project sponsor to exert significant effort in ensuring that closure happens. Failure to do so is a lost opportunity to influence perceptions—about doing work together in the future, about the importance of projects to the organization, about making it a priority to learn together and apply those learnings to future projects, and about rewarding people for their best work.

Project Management Forums

Company-wide forums for practicing project managers are often half-day sessions devoted to a specific project management topic. Specific issue forums allow for more advanced discussion of topics and the opportunity to share experiences among practicing project managers. Virtual seminars may also be conducted over the web and audio conferences, allowing people to get more exposure to good ideas.

One of the simplest, and least expensive, ways for project managers to learn from each other is through regular, such as once a month, noontime forums—“brown bag luncheons.” Anybody may organize these forums, and anybody may be a speaker. There may be a topic for discussion, or it may be open ended. Questions are asked, best practices are shared, and innovative solutions are discovered. Some organizations establish book study groups to regularly discusss business management topics and also require summaries of training sessions attended be shared with colleagues. Upper managers are wise to encourage and support such forums. When interesting ideas surface, be willing to adopt, adapt, and apply new practices.

Project Management Professional (PMP) Al Gardiner participated in a Creating an Environment workshop and shared efforts he was part of at his company to help project managers learn from each other: “As you know, [my company] is in the middle of a major cultural shift. We have not been able to hold the Friday Learning and Sharing (L&S) sessions for the past eight months or more. However, I can elaborate on the benefits we gained when we were doing them.”

Here are his responses to our questions:

• Can you describe a specific benefit they have brought, either to individuals or the organization? “The L&S sessions were specifically designed to gain knowledge of industry practice in various areas of Project Management. The benefits were many including understanding new methodologies and tools, enhancing soft skills, and gaining a deeper understanding of our own capabilities. The L&S session also included a period of PMP prep study. The attendees would step through a learning tool (in this case, PMIQ’s CD) and do practice questions. Wrong answers were researched, and an explanation of the correct answer was distributed to the team.”

• Who organizes them? “My group [IT Service Delivery] was responsible for the logistics. This is essentially having a conference room and teleconferencing capability, preparing material, researching answers, and distributing communications.”

• How do you communicate about them across the organization? “Via e-mail. First, my team was required to attend (and present articles) as part of their performance measurement. Through our contacts with other PM organizations in [our company], we invited others to attend.… While I am no longer in a position to arrange these sessions, the Director of the IT Project Management organization may be interested in doing something. Our CIO’s [chief information officer’s] strategy seems to be geared towards a projectized organization, so he may be interested in your work.”

Project Management Certification

Some organizations now use PMI’s project manager certification process as a way to ensure that their project managers are exposed to a broad array of topics and subject areas. In the process of obtaining this certification, the candidate encounters a wide variety of project managers from a spectrum of organizations. Obtaining certification does not guarantee that people can manage projects, but it does mean that they have studied and passed a test on fundamental and advanced project management practices. Certification is not always required by organizations in order to become a project manager; it is often recommended for those who wish to pursue a career in the field and usually required to manage projects for clients. Increasingly, we find PMP certification or a university master’s certificate listed in job requirements.

The Upper Management Role

The project manager selection and development process described in this chapter probably cannot happen without direction and support from upper managers. A project management council could run it, but with little chance of success. A group similar to the HP Project Management Initiative or a project office (Chapter Nine) could be formed to develop and oversee the process. Perhaps it could be assigned to an existing department such as human resources, but this is not recommended unless someone very knowledgeable about project management is in that department. The recommended approach is for a project management initiative or project office to see that the program is properly developed, implemented, and staffed to develop a cadre of trained project managers.

If upper managers do not understand, believe in, or support the project management process, it becomes very difficult for the organization to achieve excellent results from projects. It is far better for these leaders to adopt a mind-set about the positive value of project management and the attendant role of project, program, and portfolio managers. Then adapt a selection and development program to the needs and culture of the organization. Apply these concepts consistently and enthusiastically. Believe in continuous learning, both for self and others. Reap the benefits from this leadership model as applied by its followers.

The successful complete upper manager:

![]() Stops the appointment of accidental project managers

Stops the appointment of accidental project managers

![]() Develops a dual career ladder to allow people to stay in technical positions

Develops a dual career ladder to allow people to stay in technical positions

![]() Determines proper project management selection criteria for the organization

Determines proper project management selection criteria for the organization

![]() Develops and installs a project manager selection process

Develops and installs a project manager selection process

![]() Supports the creation of a course on transition to project management

Supports the creation of a course on transition to project management

![]() Supports and oversees a project manager development process

Supports and oversees a project manager development process

![]() Serves as a role model for continuous learning

Serves as a role model for continuous learning