Key 5

Find High Meanings

In exploring key 5, we need to know the answer to four questions:

- How do we gain the respect of others?

- How do we begin to involve others?

- How do we see opportunity from others’ eyes?

- How do we find the high meanings that will inspire others to change?

Let’s look at each of these questions.

How Do We Gain the Respect of Others?

When the great achievers didn’t respect the power of others, they paid a dear price— as in the case of the next visionary. His story begins in a courtroom years ago, as he was ushered in.

The Trial

A bearded old man, he walked unsteadily, his deep-set eyes piercing the room. He was fearful. In his 70 years, he had never been on trial before. His doctors had told the court that he would die if removed from his sickbed, but the court had ordered him to appear anyway.

The prosecutor, a thin, heavily wrinkled man, robed in red and purple, was seated at a small oak table. For him, this was a must-win trial. Far more was at stake than the crime; both the law and the system were on trial. The defendant had to be stopped. The prosecutor rose and, without facing the defendant, began his examination: “Do you have anything to say?”

The old man sighed deeply. “I have nothing to say.” In contrast to his thin, clean-shaven opponents, the old man was a large, swarthy man with an immense beard and a bald head that stretched far behind a deeply furrowed forehead (figure 5-1).

The prosecutor narrowed his eyes as he turned toward the old man. “Do you hold or have you held that the sun, not the earth, is the center of the universe?”

The defendant knew what he had to say to save his life: “I hold the opinion the earth is the center of the universe.”

His thoughts drifted back to the beginning. It began when he built a telescope so powerful that he could see ships 50 miles out on the Aegean Sea. When he invited members of the Venetian Senate to look through his telescope, they were amazed. Overnight, the military and commercial world fell at his feet.

The prosecutor scowled. He lifted a copy of the old man’s book, Dialogue, from the table. “Do you hold the opinion the earth goes around the sun?” He slammed the book to the table. “Tell the truth!”

“I did not write the book because I hold that opinion,” the old man replied.

“I repeat. From the nature of the book, you have held the opinion the earth moves about the sun.” The prosecutor’s voice rose to a shout. “Tell the truth! Otherwise, we will torture!”

The old man slumped in his chair. He knew that, a few years earlier, a Franciscan friar, Giordano Bruno, had been brutally tortured and then burned alive for heretical beliefs.

“I am here to obey,” he said, with what appeared to be all his remaining strength.

The old man’s thoughts drifted again. If only he’d been content to view ships at sea. But he had improved his telescope until he could see what no one had ever seen: moons rotating around other planets. He remembered being frozen to the eyepiece. What he saw contradicted Aristotle’s theory that all heavenly bodies rotated around the Earth.

The long silence in the courtroom ended when the prosecutor returned from his huddle with the inquisitor. He said that the trial was over. The old man was led back to his cell.

The next day, he knelt before his inquisitors and said in a weak voice, “I, Galileo Galilei . . . swear that I’ve always believed, I believe now, and, with God’s help, will always believe all that is held and preached by the Holy Catholic Church.”

Galileo was sentenced to house arrest for life and barred from ever expressing his views. He had to publicly apologize. His book was forbidden, and his condemnation read to professors and students of science in Italy.

He was angry. Why had they done this to him? With his telescope, he had shown them that Jupiter had four moons circling it. He was sure that they’d marvel at the power of the Creator. But they refused to “see.” Eight years later, he died a prisoner in his villa in Arcetri, just outside Florence. For more on this story, see the source for this synopsis: Galileo by James Reston Jr. (New York: HarperCollins, 1994).

For centuries, people have debated whether Galileo got a fair trial. There are good arguments on both sides. Put yourself in the church’s position. Suppose you believed that the splendor you saw above you on a dark night was heaven. Galileo was asking you to believe that you were seeing just more suns and planets. If Galileo were right, the Earth would be revolving at 1,000 miles an hour, and we’d be orbiting the sun at 67,000 miles an hour. The winds would blow us over, and we’d be flung off. A ball thrown into the air would not fall straight down. But we’re not flung off, the winds don’t blow us over, and a ball does fall straight down. It’s obvious that we’re standing still and that the heavens revolve about us.

Of course that view is wrong, but you’ll never be able to lead where others can’t lead until you learn to respect the expertise of those who have different views of the world. We’re not saying that you should condone the view of the church at that time. But you can respect and appreciate it. In his book, Galileo made fools of those who believed that the Earth was the center of the universe. These included the Pope. A leader must have more than the truth; he must know how to help others see it. When some visionaries become frustrated with those who oppose or resist their vision, they attack them. They make war and they get war; there’s a winner, there’s a loser. And when they underestimate the relative power of the resisters, they’re the losers.

Of course ideas like Galileo’s are always going to elicit opposition. The theory of evolution that Charles Darwin proposed was also highly controversial. But Darwin welcomed the challenges of others and openly questioned his own work. Darwin respected the power, expertise, and viewpoints of others. He, in turn, was so respected that many colleagues who disagreed with him did not attack him.

The Lesson of the Stone

The type of marble that Michelangelo sculpted David from is pure white marble, the finest in the world. It has been mined in the Alpi Alpuan Mountains near Carrara, Italy, since the time of the Roman Empire. This marble has the least impurities of all marble, but even it will shatter if struck in the wrong place. It’s unforgiving. The stone will not forgive a lack of expertise in carving. One wrong blow from the hammer and the stone will shatter and the sculpture will be ruined. The sculptor must not only expertly visualize the final image inside the stone but must also know where to strike the stone so it will willingly yield the final image.

Michelangelo knew the lesson of the stone. His mother died when he was a baby, and he was sent to the wife of a stonecutter to be wet-nursed. All his life, Michelangelo remembered the reverence of the old stonecutters toward the stone and their mystical words of caution: “The power lay in the stone, not in the arms or the tools. If ever a mason came to think he was master, the stone would oppose him.” For more on Michelangelo, see The Agony and the Ecstasy by Irving Stone (New York: Signet, 1961).

Great leaders know the lesson of the stone. They approach each new mission with the humility of a sculptor. They know that if they put themselves above people, people will oppose them.

As we studied great failures, such as Galileo’s, we found that leaders often failed when they thought they were superior—when they didn’t respect the expertise and power of those who opposed them. In the mid–eighteenth century, the king of England imposed stiff new taxes and laws on the American colonies without their consent. He thought they had no choice but to comply. You know the rest of the story.

Great leaders mobilize support by first respecting the expertise and power of others.

How Do We Begin to Involve Others?

Leaders who don’t see opportunity from the eyes of others make many common errors: The first error is to fail to identify and involve others early enough in the process. The second error is to not know or care about the needs and wants of others— as Galileo did. The third is to overestimate the acceptance of others, and the fourth is to underestimate the power of the opposition. To avoid common leadership errors:

- Identify and involve others early.

- Know the needs and wants of others.

- Don’t overestimate the acceptance of others.

- Don’t underestimate the power of the opposition.

Let’s discuss each of these briefly.

Identify and Involve Others Early

To identify whom to involve, a leader must imagine what the future will be like once the opportunity is seized. Two groups of people must be identified: those whose help is needed to seize the opportunity, and those whose lives will be changed by seizing the opportunity. Here’s a checklist for identifying those who must be involved:

- Who stands to gain the most from seizing this opportunity?

- Whose time, expertise, and resources are needed to seize the opportunity?

- Who are the power insiders that must be involved to seize the opportunity?

- Who needs to change what they are doing to seize the opportunity?

- Which employees, customers, or suppliers will be affected significantly?

- Who will oppose seizing the opportunity?

Know the Needs and Wants of Others

Even the great achievers sometimes lose sight of the needs and wants of others. Early in the 20th century, Henry Ford’s ability to see that his customers wanted an affordable, durable automobile made him a giant in the automobile industry. But, in 1925, General Motors introduced car buyers to variety, style, yearly model changes, and financing. At that time, Ford had lost touch with the needs and wants of his most important customers. He continued to build only one model and denounced financing as evil. By 1927, his firm had lost most of its customers. After suffering huge losses and being threatened with ruin, Ford changed his mind and provided variety, model changes, and financing.

Winning customers back was costly for Henry Ford. Research has shown that it’s much more expensive to win a new customer than it is to keep an existing one. So it’s important to know your customer’s real wants and needs.

Certainly, there are times when a leader must do what’s right, no matter what others may think they need. However, a leader will get less opposition if he or she explains the reasons for unpopular changes, because this shows people that the leader respects their needs. People still may not like it, but many will understand that it’s necessary for the long-term benefit of them and the organization.

Don’t Overestimate the Acceptance of Others, and Don’t Underestimate the Power of the Opposition

The most successful people are energized by the visions they create and are stimulated by change. On the one hand, these are great strengths. On the other hand, they’re sometimes so passionate that they can’t see a vision through the eyes of those affected by the vision. See the sidebar for how Abraham Lincoln made this mistake.

Some leaders leave the opposition out until they are sure they can seize the opportunity. All may go well in the beginning, but when the opposition hears about it, they feel left out, and the leaders lose their trust. The opposers then exaggerate rumors of changes and job cuts or whatever is at stake. Then the leaders have a battle on their hands.

Abraham Lincoln was a master of human relations. But during the Civil War, he had an ex-member of Congress, Clement Vallandigham, jailed after an antiwar speech and he revoked the writ of habeas corpus so that all critics of the war could be jailed indefinitely. He then shut down the Chicago Times because of its antiwar views. All over the nation, speakers rose to condemn the arrests, the war, and an unjust draft that allowed the rich to hire people to take their places. In New York City, police and marines couldn’t stop the mobs when they rioted against the draft. Hundreds were killed.

Lincoln’s staunchest supporters pleaded with him to back off. Lincoln, surprised by the reaction, freed the critics, allowed the Times to publish again, and reinstated the writ of habeas corpus. Even a great leader like Lincoln sometimes overestimated the acceptance of others.

Visionaries know that there is great opportunity above because they see it from below. Or, having been to the top, they know that the journey is worth it. But others may see just a few steps ahead. In general, it is a mistake to assume that others will follow. Great leaders know that others are more willing to follow when they “see” what is at the top and find personal meaning in climbing to reach it.

The best leaders identify those who should be involved early. Then, to get them to willingly invest their time, expertise, and resources, the best leaders try to see the opportunity from their point of view.

There may be no one who is better able to “see what others see” than the next master.

How Do We See Opportunity Through Others’ Eyes?

In 1976, the WJZ-TV newsroom in Baltimore received a call from a reporter at the scene of a fire. The reporter said that the station should not do a story on the fire because it was too horrifying. The news desk ordered her to cover it. Obediently, she interviewed a woman who had lost seven children in the fire. She cried with the woman as the camera rolled.

That evening, after the film was aired, the reporter apologized on the air for crying. Co-workers criticized her for her loss of control and considered her apology unprofessional. She was told that she didn’t have the “right stuff” for big-city reporting. The station gave her a second chance as a news co-anchor but quickly removed her.

Then a new manager decided to create a morning talk show to run opposite the popular Phil Donohue show. The ex-reporter was selected as a co-host. Most believed that the show had a slim chance of success, but the ex-reporter had something the odds-makers didn’t know about. She was a genius at finding the human-interest side of a guest’s story and asking questions that the audience wanted to ask. She won the respect of guests because she gave them respect and was genuinely interested in them. For example, guests knew that if they had been abused or unsuccessful with dieting, she understood. Soon, all Baltimore was talking about her, and the show ratings climbed. She said to herself, “This is what I should be doing. It’s like breathing.”

Of course, we’re talking about Oprah Winfrey. Oprah had found a career she had a passion for, one in which her apparent weakness—her ability to see from others’ points of view—was valuable human expertise. For more on this story, see the source of the material above: The Uncommon Wisdom of Oprah Winfrey by Bill Adler (New York: Carol Publishing, 1997).

These days, The Oprah Winfrey Show is seen by 20 million viewers a week. People invest hundreds of millions of dollars in the products she supports. Oprah used her leadership and business expertise to build a billion-dollar business. She has a lesson to teach all of us: When we learn to see from others’ points of view, we show our respect for them and we gain their respect.

The Customer’s Point of View

Intuit Corporation, the maker of popular personal and small-business accounting software, continually searches for what existing customers “see.” All Intuit employees, including the CEO, are required periodically to staff the customer service telephones and respond to and solve customers’ problems. Customer thank-you letters are posted on the company’s walls for all to see. At company meetings, the first items on the agenda are customer service trends, problems, and victories. This tells the employees what the customers “see” and what the employees are doing to please the customers. For more on this approach, see Extreme Management by Mark Stevens (New York: Warner Business Books, 2001).

Seeing from the customer’s point of view has created breakthrough marketing approaches. See the sidebar for examples.

The Employee’s Point of View

Finding what it takes to energize employees to give more than what the job requires is an important leadership function. Employees may want more training or increased responsibility in their jobs. They may want to have a say in how the work is done. They may want to be part of a mission with a high purpose. They may want more job security. It is important to see the world from their points of view.

Dozens of patents were awarded for safety razors around the turn of the 20th century. Among them was one by King Gillette. His razor was different from, but not superior to, many of the others. It cost a dollar to produce his razor—more than he could sell one for. But Gillette figured out the shaver’s point of view. The shaver would buy his razor if it were priced at 55 cents, well below the competitors’ prices. After that, the shaver would willingly pay 5 cents each for the blades. As a blade cost less than 1 cent to make, Gillette could afford a big loss on the razor while making a profit on sales of blades. He made money on the shave, not on the razor. Xerox did a similar thing by placing expensive copiers in offices and charging 5 cents a copy. These and other stories are related by Peter F. Drucker in The Essential Drucker (New York: Harper Business, 2001).

How Do We Find the High Meanings That Will Inspire Others to Change?

Great leaders search for the high meaning that will inspire others to give their minds and hearts. In 1940, personal survival was on every British citizen’s mind. At that time, Great Britain stood alone in Europe against a mighty German war machine that had swept through Poland, Czechoslovakia, and France. It was clear that Hitler would soon attack the British homeland. As concerned British citizens huddled around the radio, the prime minister, Winston Churchill, spoke in the clipped and inspiring tones he was famous for:

HITLER KNOWS HE WILL HAVE TO BREAK US ON THIS ISLAND OR LOSE THE WAR. IF WE CAN STAND UP TO HIM, ALL EUROPE WILL BE FREE, AND THE LIFE OF THE WORLD MAY MOVE FORWARD INTO BROAD, SUNLIT UPLANDS. BUT IF WE FAIL, THE WHOLE WORLD, INCLUDING THE UNITED STATES, INCLUDING ALL WE HAVE KNOWN AND CARED FOR, WILL SINK INTO THE ABYSS OF A NEW DARK AGE. . . . LET US THEREFORE BRACE OURSELVES TO OUR DUTIES AND SO BEAR OURSELVES THAT IF THE BRITISH EMPIRE AND ITS COMMONWEALTH LAST FOR A THOUSAND YEARS, MEN WILL SAY, THIS WAS OUR FINEST HOUR.

Churchill’s speech roused the spirit of the people, elevating them above their fear, above their self-interest. In the darkest hour of the 20th century, he stood like a shining light. He knew what influenced human action. The quotation above is from The Penguin Book of Historic Speeches, edited by Brian MacArthur (New York: Penguin Books, 1996). The context in which the speech was given is from Churchill: A Life by Martin Gilbert (New York: Henry Holt, 1991).

There are many theories about what influences our actions. Some of the most respected theories are:

- Meanings are programmed in us for survival and adaptation.

- Our culture greatly influences our adaptive behavior.

- There is a hierarchy of human needs.

- We all have a need for meaning.

Let’s look at each of these basic theories.

Meanings Are Programmed in Us for Survival and Adaptation

Some anthropologists theorize that humans are programmed to survive and adapt by rewarding two opposite behaviors: caution and adventure. It’s as if we are pulled in two opposite directions:

- The adventurous pull rewards us for exploring, risk taking, discovering, pushing our limits, and fighting.

- The cautious pull rewards us when we rest our minds and bodies, conserve our energy and resources, preserve ourselves, and flee from danger.

One opportunity may have very different meanings for different people. The cautious individual may see danger in the opportunity, while the adventurous individual sees excitement and rewards. Most leaders are on the adventurous side, and they often are impatient with those on the cautious side. They prod others to explore, to take risks, to set unimaginable goals, and to make changes.

Our Culture Greatly Influences Our Adaptive Behavior

The Chinese were the first to make paper, to make silk, to use block letters to print, to invent gunpowder, to create the first water-driven machine for the spinning of hemp, and to use coal and coke in blast furnaces. Although they found all these opportunities, the opportunities all were seized and turned into huge enterprises by the Europeans.

In Why Are Some So Rich and Others So Poor? (New York: W. W. Norton, 1998), the researcher David S. Landes says that not only did the ancient Chinese lack free markets and property rights, they didn’t seize these opportunities because they valued tradition, and the leaders wanted to keep the power in their hands. They were cautious, whereas the Europeans were adventuresome. The Chinese culture today is becoming more adventuresome and more successful.

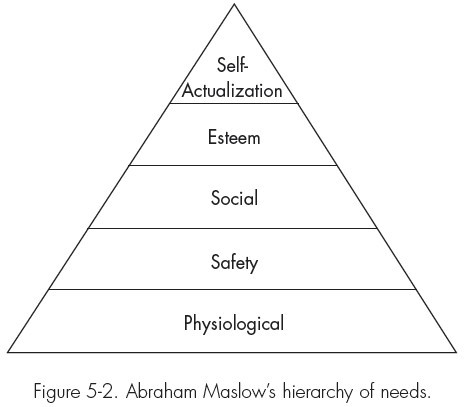

There Is a Hierarchy of Human Needs

Another popular theory is the psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs; see his Maslow on Management (New York: Wiley, 1988). According to Maslow, basic needs at the bottom of the hierarchy must be satisfied before higher needs become important. Maslow said that whatever needs a person is experiencing affect the person’s motivations, priorities, and behaviors. Unsatisfied needs create the motivation to satisfy them. People need to satisfy the needs at each lower level—at least partially— before they can move on to a higher level, ultimately self-actualization. Together, these needs form a pyramid (figure 5-2).

Many people in industrial countries today are not focusing on mere survival. Thus, they can focus on creating new products and developing themselves. In the more advanced countries, each year, more work requires innovation, and those who can innovate are functioning higher on Maslow’s pyramid. Leaders in advanced countries who help people move toward the top of the pyramid will get them to give more than what is required.

Some behaviorists say that the higher the purpose, the higher the meaning. People do volunteer work partly because they believe in what they’re doing. If they are asked to do work that they don’t enjoy doing for a good cause or a higher purpose, many would probably do it, even though that wouldn’t necessarily be the best use of their expertise. Others might resist. It isn’t enough for an organization to have a high purpose to get people to dedicate themselves to its mission. The best volunteer organizations we studied discover a volunteer’s expertise and place the volunteer in a job where the person will be challenged to use that expertise to the fullest. Many volunteers were more enthusiastic about their unpaid work than about what they did for a living.

The more freedom of choice and opportunities people have, the more they must work to find ways to make their willing contribution to achieving the mission. The most progressive of today’s leaders treat all people they lead as if they’re volunteers.

As the amount of available knowledge increases rapidly, businesses must acquire knowledge more rapidly and more effectively to remain competitive. This means that a worker’s knowledge and ability to use it are vital resources. Therefore, knowledgeable people have to be managed as if they were volunteers.

We All Have a Need for Meaning

Another relevant theory is about humanity’s need for meaning. Meanings are powerful beams of light in the worst darkness. In Man’s Search for Meaning (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), Viktor Frankl, who survived German concentration camps, says that those who survived had meaning that made the brutal conditions tolerable. Some felt that they needed to take care of loved ones or that they still had unfinished work. Others felt that surviving was a way of winning against their hated captors. Frankl proposed that the highest meanings are those for which people will endure any difficulty and choose to survive when death would be easier. He believed that meaning is the best motivator for development, improvement, and change. The meaning that something or someone has for us includes:

- the value, moral or psychological significance, need, or importance to us

- what we stand to lose by its or the person’s absence

- what we stand to gain by acquiring it or having the person in our lives.

In general, no matter what theory of human behavior they were inclined to believe, the great leaders always searched for higher meanings when they were trying to influence others to change.

Converting People Into Investors

Our research team found that great leaders influenced others in a way we couldn’t put into words. Traditional words, such as ownership, participation, and involvement, didn’t describe how they led. Then one of our researchers suggested that great leaders convert people into investors.

Initially, no one agreed with her. But she said that the team members were thinking too narrowly about the word “investor.” She asked them to think of broader definitions of invest, such as “devote time or provide ideas to a purpose” or “contribute effort to something in the hope of future benefit.” For example, if someone on your staff willingly proposes a better way to do a job, she’s an investor. However, if she thinks you won’t listen to her, or that she’ll lose if her idea fails, she may not invest. If one of your engineers willingly works unpaid over a weekend to test a new product, he’s an investor. The time you willingly give your children is an investment.

Our researcher said that thinking of people as potential investors of their time, ideas, and resources greatly improves how we approach them for their help. In time, we all agreed that converting people into investors is the best way to describe what great leaders did to mobilize people to seize opportunities. We decided that, from that point on, we would define an investor as “any person or group that willingly gives time, ideas, or resources to seize an opportunity, in the hope of future benefit.”

So, to mobilize support, we should first identify those who should be involved and then learn what meanings influence their behaviors. We are then prepared to convert them into investors with the help of the next three keys: co-creating with the eager ones, selling the cautious ones, and negotiating with potential opposers. It’s important to be skilled in the use of these keys. It’s also important to know which key will be most effective with each group.

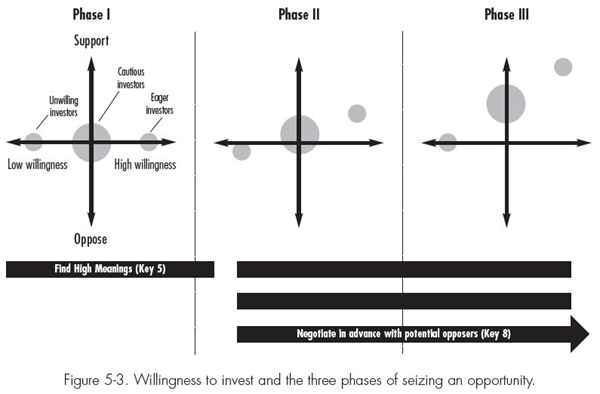

Willingness to Invest

When an opportunity for success is first introduced, people’s willingness to invest varies widely. As shown in phase I on the left side of figure 5-3, people can be divided into three groups, according to their willingness to invest and what has the most meaning for them.

These three groups can be described this way:

- A small group of people, the eager investors—sometimes called early adopters or pioneers—is looking for opportunity and is willing to change. Seizing the opportunity has high meaning for them.

- A much larger group, the cautious investors, wants to keep things the way they are, because keeping things the way they are has high meaning for them. Many of them are pragmatic, however, and can be sold on the opportunity.

- Another small group, the unwilling investors, initially may oppose the opportunity, either because the individuals believe that the opportunity is against their interests or because they’re championing other opportunities that compete for the same resources. Blocking the opportunity has high meaning for them.

Figure 5-3 shows the three typical phases of how you can seize an opportunity. In phase I, you apply key 5 to identify investors and what meanings influence their behavior. You search for their higher meanings.

In phase II, you apply keys 6, 7, and 8 to gain support from eager and cautious investors while keeping potential opposition from unwilling investors in check. Note that the leftmost circle, which represents unwilling investors, moves down and becomes an opposing force. This is the typical reaction from this group, and only continued use of good technique can bring them up to a more neutral position.

Phase III shows that the proper implementation of keys 6, 7, and 8 will typically result in a distribution where maximum support is achieved from eager investors, strong support is achieved from cautious investors, and the opposition from unwilling investors is mostly neutralized.

These techniques, as outlined in figure 5-3, are covered in detail in keys 6, 7, and 8. In key 6, we’ll first consider how to best get the willing support of eager investors.

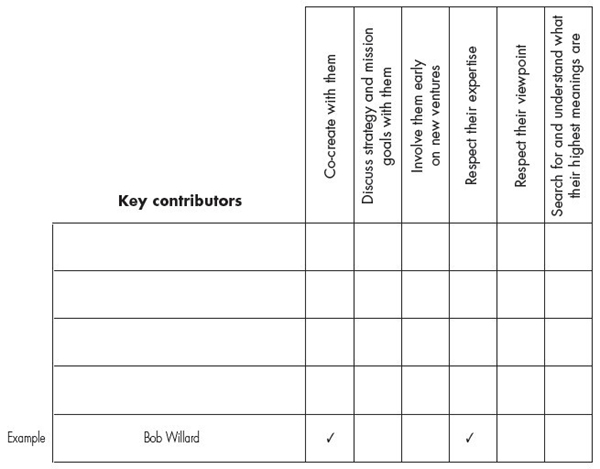

Self-Evaluation Exercise: Maximize Support for Pursuit of Opportunity

List the key people most important to your business or personal goals and opportunities in the left-hand column below. Check the boxes that most accurately reflect how you interact with them.

Look for any opportunities in the above list to create investors and volunteers from your key contributors.