Key 1

Differentiate Yourself

It is not enough to have a good mind. The main thing is to use it well.

—René Descartes

For years, a German clerk worked by day at a patent office in Zurich as a patent reviewer because no one would give him a job in physics, his chosen field. After work, he returned to his drafty, one-room apartment in Zurich to spend his evenings studying the mysteries of time and motion. In 1905, this unknown clerk published papers on Brownian motion, the photoelectric effect, and the Theory of Relativity. The paper on the photoelectric effect eventually won him a Nobel Prize. The paper titled “The Special Theory of Relativity” changed the face of physics forever.

This clerk, Albert Einstein, suffered from dyslexia and, up to the age of seven, had difficulty speaking, having to repeat words to himself slowly. As a child, he was mentally slow and failed mathematics in his early school years. His teacher advised his father that he needn’t concern himself with choosing a line of work for his son, because the boy wouldn’t amount to anything. Until his research papers catapulted him to international fame, he was an outsider and ignored by his peers in science (figure 1-1).

By the age of 20, Einstein had obtained a degree in physics from the Swiss Polytechnic School, with a B average. His professors gave him poor evaluations, saying that he was rebellious and skipped classes. With poor evaluations, he couldn’t get a teaching post or a job in physics, so he took the job as a clerk.

The research team for this book struggled with Einstein. Some said that lessons learned from geniuses don’t apply to the average person. Then one researcher asked, “If Einstein had chosen to be a great patent reviewer, would we consider him a genius today?” The other researchers agreed that the answer was “no,” because Einstein had no passion for patent review, he was not exceptional at it, there was no opportunity in it to do something revolutionary, and he had little chance of great rewards. His passion, talent, and potential rewards were in physics, and that’s where he searched for opportunity.

The Gateway Key to Success

The “great achievers”—the great leaders who are the source of the 10 keys—knew where to focus their life work to achieve success. They focused on three basic factors:

- where they had passion for their work

- what they did far better than others

- where there were potential rewards for their work.

The great achievers thus chose to work where their passions, their abilities, and their potential rewards were all high. For example, the young Thomas Edison chose to be a telegraph operator because he loved it, was good at it, and the telegraph was the Internet of his time.

But what about Leonardo da Vinci? If he had been allowed to follow the field of his ancestors and became a notary, would we consider him superhuman? We suspect he would have become a great notary and businessman, and he would have been admired and respected in his times. However, it’s hard to imagine that we would think of him as superhuman today.

Finding Where to Search Late in Life

Some people spend years searching for opportunity where the rewards will never be there for them. But the great achievers never stop searching. Colonel Harland Sanders is a good example. All his life, he moved from sales job to sales job, living from paycheck to paycheck. At the age of 65, he finally found his opportunity when he moved to Corbin, Kentucky, to run a gas station. To increase sales at the station, he started serving fried chicken made from his special recipe. Business boomed.

Then a new interstate highway bypassed Corbin, and the business failed. Devastated, Sanders assessed his life. He decided that he knew how to fry chicken better than anyone else, loved to cook, and loved to sell. So he traveled around the country calling on restaurants. He would cook a batch of chicken for each owner, and then sell a franchise. By the age of 75, he had more than 600 franchisees. He never settled until he found a way to differentiate himself from the crowd and, when he did, he found great opportunity.

Organizations Change How They Are Differentiated

The noted researcher Jim Collins found that great organizations can also change late in life if they realize that they no longer can be the best at what they do. He uses the example of Abbott Laboratories, which knew in 1964 that its competitors like Merck had powerful laboratories that made them the best in the world at creating drugs.

Although Abbott’s core competence and principal source of revenue was drug production, its leaders knew that it couldn’t continue to be the best in this field in the long run. So they searched for what Abbott could do best. They decided to create products that make health care more cost-effective, products that help a patient regain strength quickly after surgery, and diagnostics that improve a physician’s ability to find the correct causes. Today, Abbott continues to be successful in the health care field. For more, see Collins’s book Good to Great (New York: HarperCollins, 2001).

Not only do great organizations differentiate themselves, but they are also led and managed by individuals who had to learn to differentiate themselves personally. That’s why this book begins with how individuals have used the 10 keys to leadership.

Great organizations like Abbott Laboratories have been able to change how they are differentiated when one of their three success factors is no longer at the optimum. Often, however, organizations and individuals keep doing what they are best at and passionate about despite overwhelming evidence that what they are doing is no longer driving their economic and creative engines. For an example, see the sidebar on IBM.

Three Key Questions

Some people and organizations choose where they search for opportunity by weighing available alternatives—as if they were solving problems. But the great achievers have taken a better approach, analyzing areas of opportunity and asking themselves:

- What am I most passionate about?

- What can I do far better than others?

- What can bring me the highest rewards?

Each of these questions captures one differentiating factor. Let’s consider each question in the light of a modern success story.

What Am I Most Passionate About?

In 1968, two boys, Bill Gates and Paul Allen, were intrigued with a computer terminal that had been installed in their high school. They began to devote long hours learning to operate it. Within a year, the 12-year-old Gates had written a small computer program to play tic-tac-toe. Although it took longer to play than it did with pencil and paper, Gates was fascinated with the program.

Within a few years, the boys had learned enough to make money doing small programming jobs for local firms. They invested the money they made into more computer terminal time. Both of them had so much passion for computer programming that they spent all their free time doing it (figure 1-2).

IBM went through an agonizing period in the early 1980s, when the computing power of small, low-cost computers began to rise rapidly, and other companies were providing integrated solutions to their customers. IBM’s leaders had a passion for building large, mainframe computers, and they did it better than anyone else. So they continued to focus nearly all their resources on mainframes. They didn’t transform IBM into an integrated-solutions provider until it suffered large financial losses.

What Can I Do Far Better Than Others?

During those early days at the high school computer terminal, Gates realized he was not only good at computer programming; he could be far better at it than anyone else. Like him, most of the great innovators and achievers have discovered from experience what they do well and what gives them uniqueness and a competitive advantage compared with others.

Recent research by Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman indicates that the most successful managers focus on discerning what their staff members do better than others and then placing them where they’ll perform best. This research analyzed 80,000 interviews with managers, conducted as part of a Gallup Poll; it’s reported in Buckingham and Coffman’s book First, Break All the Rules (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999).

What Will Bring Me the Highest Rewards?

In 1972, Gates and Allen bought one of the early microprocessors and tried unsuccessfully to program it to run the computer language BASIC. So they programmed the microprocessor to measure traffic data. The traffic machine worked but was not a commercial success. Through these failures, they began to believe that they could make money in the computer business if they just found the right application. Then, in January 1975, they discovered that Altair was advertising a small $400 computer. They feared that the computer revolution had started without them.

But they noticed that the advertised computer had rows of switches on its front plate that had to be programmed by hand, meaning that it didn’t come with any useful programs. They immediately told Altair that they had a BASIC program that would run on its machine. Then they worked around the clock to prove they could actually do it. Gates wrote the BASIC4 program while Allen found an ingenious way to test the program on a large mainframe computer.

Then Allen flew to Altair’s headquarters in Albuquerque, New Mexico. In the presence of the owner of Altair, he held his breath as he loaded the program. When the teletype printed the word “ready,” he typed in “print 2 + 2.” Immediately the teletype printed the answer “4.”

All those watching knew that they’d just witnessed the birth of a personal computer. Altair’s owner was ready to make a deal. Gates and Allen were in on the ground floor.

They chose where to search for opportunity based on what they could be rewarded for doing, what they had a passion to do, and what they could do better than anyone else. Allen quit his job at Honeywell, and Gates dropped out of Harvard. They named their new company Microsoft.

Life Purpose Is Woven Into Each Differentiating Factor

Purpose is a powerful driver of passion. People who find high purpose in their work also have high passion for the work. People who can do something far better than others often find high purpose in sharing their talents and expertise with others. When you are rewarded highly for what you do,

- you are able to support your family

- you can contribute to the lives of others

- you can use your resources to influence important community and world events.

The great scientist Marie Curie was driven early in life with the purpose of obtaining a Ph.D. at a time in Europe when no woman had ever been awarded one. Knowing what she was up against, she differentiated herself by choosing physics, a field for which she had a passion, in which she was far better than others, and in which she thought she might be able to get a PhD. Later in life, when she had been highly rewarded, she made it her purpose to cure cancer.

Collins found that corporations that had great performance over a 15-year period chose where they did business based on three factors:

- what they could be best at

- what they had a passion for

- what drove their economic engines.

These are the same success factors that great individual contributors have used to choose their fields of work.

The great achievers have focused first on doing the right things for success. Then they have focused on doing things right.

After determining where they have the best chances of finding success, the great achievers have devoted a great part of their time to learning the most valuable knowledge and skills in the fields or markets in which they chose to work. In doing that, they have discovered some very powerful learning processes. In other words, after they have decided where to search, their next key was to find what was best to learn and how to best learn it. The exemplary great achiever described in the second key was an exceptional learner. He used powerful learning processes to create the largest corporation on earth.

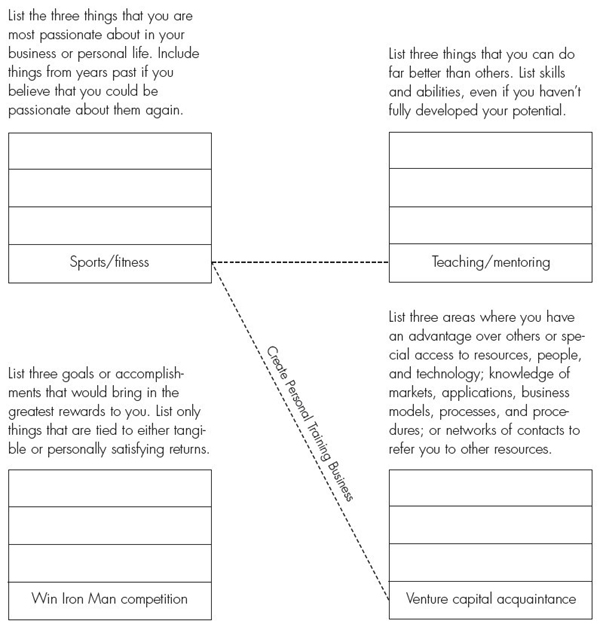

Self-Evaluation Exercise

Self-Evaluation Exercise

Next, draw lines between all the above differentiators in each of the four categories that are related or could be combined in the pursuit of opportunity. (Note the example of personal training given here.) Then, on the lines between any two differentiators, write an opportunity that could be pursued by taking each of these distinguishing features and discovering an activity that combines both. If an opportunity can be pursued that connects three or more categories, the potential for extraordinary results is increased.