Chapter 4

Step 2: Focus on What Matters

![]()

Being busy does not always mean real work. The object of all work is production or accomplishment…. Seeming to do is not doing.

![]()

Today, when organizations are facing more and more competition (and even non-profits and government are outsourcing functions), there is tremendous pressure to get it right and perform well. Yet at the same time, ironically, there is a tremendous focus on things that are comparatively less important.

How can this be? You would think that managers would have the sense to emphasize what is most important and measure what matters. But the reverse tends to be true. In the vast majority of organizations, managers monitor and measure people on issues that are typically not that valuable to the business while deemphasizing what matters most.

The Mistake of Focusing on Behavior

![]()

Perfection of means and confusion of ends seems to characterize our age.

![]()

The most common mistake when it comes to performance is to focus on behavior (Harless 1989). Most managers hire, monitor, and fire or promote based on how employees behave. And this is a critical mistake for organizations that want to be effective.

Let's define behavior in a broad sense—as not only people's actions but also their attitudes. And most organizations put a tremendous amount of importance on actions and attitudes. Managers go to great lengths to make sure that employees behave in a particular way. Many books, executives, and consultants swear that if only you get people with the right skills, the right behavior, or the right attitude, you're guaranteed to be successful. Some organizations swear by particular temperament tests or design behavioral profiles for ideal workers.

If you doubt that most organizations focus on attitude and behavior, just look at a copy of your most recent performance appraisal. It probably assesses you on things like your communications skills, ability to work with others, leadership skills, and knowledge of your job. Although none of these is irrelevant, none assesses how well you performed or helped your organization get closer to its key objectives. Just because you have talent doesn't mean you performed well. As Pfeffer and Sutton (2006, 86) conclude in their analysis of evidence-based management, “the best evidence indicates that natural talent is overrated, especially for sustaining organizational performance.”

This problem is compounded by the tendency of organizations to focus not only on irrelevant things but also on the wrong things. The business and management literature is replete with arguments about how if only people would behave a particular way, organizational success would follow. But if you go into an organization and ask who is a team or department's best employee, you'll often get an answer about the person who shows up on time, greets everyone in the hall, works hard, brings bagels to meetings, and is helpful to others. Although this sounds like a really nice person, it's a definition of “best” that says “we want everyone else to behave this way.” Except for some departments like Sales that tend to be very focused on the bottom line (Who had the biggest customer volume this week?), too many organizations operate this way. Instead of focusing on employees' abilities to generate results, they focus on their behavior or attributes.

The basic assumption behind this focus on behavior is that if an organization has talented people with the right attitudes, knowledge, and skills doing the right things, good performance will follow. This premise is wrong. According to Pfeffer and Sutton (2006, 90), “Despite claims in The War for Talent, Topgrading, and numerous other books on hiring the best people, the talent mind-set is rooted in a set of assumptions and empirical evidence that are incomplete, misleading, and downright wrong.” Plenty examples illustrate how flawed this talent assumption is—just look to sports all-star teams, collections of great players who may not play well together against a less-talented but better-organized and efficient team.

The belief that a good organization is primarily a collection of talented individuals ignores the reality of organizational dynamics. How an organization functions has more of an impact than the talent level of its employees. Pfeffer and Sutton note one example (2006, 96): “NASA's space shuttle program provides a painful illustration. It is a classic case of smart, hardworking and well-meaning people trapped in a system with such ingrained flaws that even a horrible accident, the Challenger shuttle explosion in 1986, didn't change it much. That is the conclusion reached by the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, a blue-ribbon panel charged with determining why the shuttle Columbia disintegrated upon reentry on February 1, 2003.”

This does not mean that individual talent is irrelevant or that building employees' skills is a poor investment. But it does mean that collecting talented people doesn't mean the organization's overall performance will reflect their individual talents. Many variables make up organizational performance. An organization's systems have the most impact on how well it performs (Pfeffer and Sutton 2006).

![]()

We're all very good at faking things that we have no competence with.

![]()

Behavior does matter. But in the vast majority of cases, it matters only to the extent that it contributes to the results the organization wants. This is not an argument for allowing workers to behave any way they want. Part of the problem with focusing on how employees behave is that, inadvertently, managers start to act as if behavior was the goal, when it usually is really only a way to help achieve a particular result. And it's very hard to fake results but pretty easy to fake knowledge or behavior.

![]()

If you've stopped breathing, who do you want to show up? Paramedic 1: “I know how a resuscitator works.” Paramedic 2: “I know how to work a resuscitator.” Or Paramedic 3: “I have accomplished resuscitation before.”

![]()

On an average day, you can survey the employment ads online or in the newspaper and run across more than a few that ask for a job applicant who is a “self-starter.” Leaving aside the subjective question of what exactly is a self-starter, it's important to ask what is the value of a self-starter to any organization.

For instance, imagine that you had hired someone who was a self-starter or exhibited whatever positive behaviors and attributes that you associated with a self-starter. This self-starter employee of yours would possibly be someone who takes initiative, doesn't need a lot of direction, has confidence, demonstrates energy at work, works hard, and can work alone. On the face of it, that sounds like a pretty good employee. Now imagine that your self-starter exhibits all these behaviors and yet doesn't execute or perform. You may be thinking that such a scenario is impossible, because any self-starter would be productive.

But this scenario is true, even for different characteristics—say, hustle. What organization wouldn't want an employee who hustles, especially one who outhustles everyone else? But imagine that this employee outworks everyone else yet accomplishes less. There are many plausible explanations: Effort doesn't equal performance. The employee could be inefficient. The employee may be omitting key steps necessary to get results. So the company ends up with an employee who outworks everyone else but has nothing meaningful to show for it.

Now, most managers would insist that if you had an employee who hustled, this employee would be more productive—getting more reports written or more boxes filled. But here the manager is confusing what he or she wants (reports or filled boxes) with behavior (hustle) and assuming that if the manager gets the hustle, the results will naturally follow. And this simply isn't true.

Furthermore, even if hustling were always associated with getting more done, it would make more sense to track what gets done rather than hustling behavior, because it would be simpler and more direct to measure what the organization values (Gilbert 1978). An employee's real value to the organization is his or her performance—the additional reports finished or extra boxes filled. And this performance is what the employee should be managed to do, and how his or her performance should be measured.

This concept is true even if we consider knowledge or attitudes instead of behavior. For instance, an employee might have a PhD, implying expertise in a particular subject. But clearly, just being knowledgeable (or credentialed) about something does not guarantee that this individual will be a strong performer. Some knowledge is necessary for good performance and it's better to have smart employees, but it doesn't necessarily follow that smarter employees will get better results. In many instances, smart employees who know how to perform well don't—because they don't care, lack support, or have insufficient resources. And given the high cost of training (because of downtime away from work), training often has a negative return on the organization's investment.

As for attitudes, a retail sales organization might look for associates with a positive attitude and a friendly nature so customers will find them easier to deal with. But if the sales staff is very friendly and positive yet fails to get any sales, would their managers be OK with that? Of course they wouldn't. In this instance, the managers are focusing on the sales associates' attributes with the assumption that their friendly, positive nature will lead to sales. Although these behaviors of course can contribute to sales, it doesn't follow that people with them will automatically generate many sales (Gilbert 1978).

Accomplishments versus Behavior

![]()

The secret of achievement is to hold a picture of a successful outcome in mind.

![]()

Instead of focusing on how employees behave or their attributes, the smart manager focuses on what employees can accomplish (Gilbert 1992). An accomplishment is something the organization values that the employee provides. For instance, many call center managers listen in on conversations between the call center staff and customers. This is often done to check behavior and make sure that the employees are following standards and behaving courteously (such as calling customers by “Mr.” or “Ms.”). What is the purpose of the staff behaving courteously? Logically, so the customers will feel they are being treated with respect.

But here it is a fallacy for the managers to focus primarily on the behavior of the call center's employees. The employees could follow the behavior standard and still fail to accomplish the result—customers who feel respected—because either the behavior isn't sufficient or other employee actions (interruptions, failure to understand the caller, not answering the call quickly enough) are offsetting the behavior. Instead, the managers should judge their employees' performance by checking with their customers—using a survey or focus group—to determine if they felt respected. Listening in and tracking the employees' behavior won't tell if the desired result—customers who felt respected—has been achieved.

![]()

Hell! There ain't no rules around here! We're trying to accomplish something.

![]()

Furthermore, too many products have production processes that allow multiple ways to achieve the same final result. This is especially true of intellectual and service work (Pepitone 2000). Analysis, decisions, and internal approaches all can vary yet often still produce a similar result. So, for today's service and brainware workforces, it is often counterproductive to insist that everyone behave the same way.

Therefore, in assessing performance, focus first on employees' accomplishments rather than their behavior (Harless 1989). Here are several easy tests to help you determine what is or is not an accomplishment:

1. Can you assess the possible accomplishment when the employee isn't working or has gone home? To assess attributes, attitude, knowledge, and behavior, you almost always need to observe the employee doing something. But the vast majority of accomplishments can be measured or assessed even after the employee has left. How many sales were made? Is the customer satisfied? Is the power washing complete? Is the database accurate and up to date?

2. Does the possible accomplishment have value for the organization? For instance, an employee's hustling is usually only valuable because of what the hustle is supposed to produce. But the organization is really seeking what follows the hustle—more accounts serviced, more clients satisfied.

3. If the organization got this possible accomplishment and nothing more, would it be satisfied? To elucidate this point, consider these comparisons: first, approaching the customer to determine if they have any questions versus, second, closing a sale with the customer; first, a programmer who knows the contacts at various Internet software security firms versus, second, a secure corporate website; and first, an administrative assistant who knows Microsoft Word and PowerPoint and is willing to work through lunch versus, second, a report that is accurate and on time. In each instance, the only reason the organization cares about the first is because it can potentially produce the second.

![]()

Throughout school I was always told what I needed to know or be able to do but never for what purpose.

![]()

Try it for yourself. Identify a couple of your actions at work—attend the meeting on the status of the project, review field reports from the client, answer a call from senior management. What would the accomplishments be for those actions? The ultimate desired result would probably be something like “a successful organization” or “increased sales.” But to achieve these goals, interim results must be produced. So if you listed “attend the meeting” as one behavior, then the accomplishment for it is probably “a team informed about the project status and in agreement on next steps.”

Think of the implications for this. Most people in practically all organizations rail on about the amount of time wasted in meetings. And for most organizations, meetings are about the behavior—calling a meeting, attending the meeting. But imagine what it would be like if organizations primarily focused on a meeting's results rather than on scheduling and attending it? When the focus is on the activity (scheduling the meeting, being at the meeting, following the schedule or agenda), you get organizations that hold many meetings because that is what, in part, the organization is measuring. But when you instead focus on the accomplishments, you change what you end up with. There is indeed some truth to the claim that you get what you measure.

Remember, an accomplishment is something that the organization finds valuable (Gilbert 1978). Hustle by itself is rarely something that is truly valuable to a business. Communicating well, by itself, is rarely valuable to an organization, in the sense that it isn't an end. Smiling at customers, by itself, rarely is worth anything. These behaviors matter mostly to the extent that they result in something useful to the organization (such as more work done, faster results due to clarity of instructions, or great customer retention)—as shown in table 4–1.

However, sometimes how an employee behaves might itself be an accomplishment. For instance, if a group of workers is always on view to customers, then appearing busy (or hustling) could come close to being an accomplishment—not because you expect the employees to get more done, but because you want the customers to perceive the employees as being busy and active. Thus, here the accomplishment is that the customers perceive the workforce to be hard working and dedicated to their jobs. It hardly matters if the employees produce anything; their purpose is to create the perception of hard work.

Thus, the means sometimes are the ends. If a proposal is put out to bid within a government agency, the most critical result is probably that the agency has followed contracting procedures (or the proposal will likely be rebid). Therefore, the accomplishment would be a bid award that complies with contracting regulations. If this sounds confusing, remember that the defining element of any accomplishment is its value to the organization. Most behaviors or attributes have no value by themselves; only the outcome of that behavior produces an accomplishment.

Table 4–1. Examples of Behaviors versus Accomplishments

| Behavior | Accomplishment |

| Calls client about status of order | Client is aware of order status |

| Directs dock crew to follow loading instructions | Container is loaded by deadline, contents match checklist, no products damaged |

| Answer all incoming calls professionally and with a pleasant demeanor | Caller feels respected and listened to |

| Manages time well and works hard | All assignments are complete, on time, and to standard |

| Asks all callers for name and company information | Accurate log of all incoming calls |

| Reviews lines of code within program to identify conflicts and gaps | Bug-free program that does not crash |

| Reviews project plan schedule and resources requirement | Accurate and realistic project plan |

| Prepares materials before marketing visit and anticipates possible objections | A sale |

The Rationale for Focusing on Accomplishments

Accomplishments, of course, are what has value to the business—this is probably the best reason for focusing on them. If you want to perform as a company, then at a minimum you want people who can accomplish all they can individually. You're not going to get results when the organization is filled with people with the right behavior but failing to produce. Yet there are other reasons why focusing on accomplishments instead of behavior is critical.

The Error of Seeing Only One Right Way

Some managers and executives insist that a particular behavior is vital to achieve a specific accomplishment or that the behavior and result are so closely linked that it makes perfect sense to track and manage the behavior. For these managers, it's critical to focus on behavior because there is only one right way to do something or to achieve the result they want. This argument is wrong because in today's workforce, with the multifaceted nature of most work, it is becoming harder and harder to specify the behavior that employees must follow (Pepitone 2000).

To illustrate, consider this story: A mother happened to watch from her living room window as her teenage son mowed the front lawn. What should have been a relatively uneventful activity was actually turning into the evening's entertainment. After the son had completed a few passes with the lawnmower, the father intervened. The son wasn't mowing the lawn the way the father had been taught to mow the lawn, and good old dad started showing the son the correct way to cut the corners. Being a teenager and in high school, the son was somewhat resistant to what he perceived as micromanagement by his father.

After the son completed a few more passes on the lawn, dad made another appearance to show the son the error of his ways. What should have been a relatively straightforward assignment turned into a series of arguments and recriminations, and both parties (father and son) were convinced that the other was stubborn, had refused to listen, and didn't know what he was talking about. The mother's comment afterward was “As far as I was concerned, I wanted him to make the tall grass short with no one getting hurt and nothing getting damaged.”

This little story illustrates the problem with focusing on behavior at the expense of results. Managers tend to focus on behavior because they are convinced that there is one correct way to do a job, when in reality the managers are only seeking to have people do work they way the managers themselves were taught to do it.

Beyond Scientific Management

In the late nineteenth century, Frederick Taylor coined the term “scientific management” in part because of his approach to designing more efficient means of working. During that day and age, when many Americans worked in manufacturing and did primarily blue-collar work, it made a tremendous amount of sense to design jobs that specified how they were to be done and what tasks in what sequence. After all, it doesn't work to have everyone on the assembly line freelancing or doing things differently each shift. Taylor's work helped create the study of ergonomics.

But most jobs have changed since Taylor's day. Although everyone is not in the service economy or working in a white-collar job, most jobs (including blue-collar and manufacturing ones) require more and more decision making and discretion from employees. Why does this matter? The more elements of a job that require mental processing (such as making decisions about what to do next or determining if something meets standards, or adapting to the circumstances), the more variability there is to the work. As the performance consultant James Pepitone (2000, 77) notes, “Taylor's strategies for improving the efficiency of machine-like factory labor in the 1920s have already proven themselves ineffective with today's more sophisticated workforce…. The very different nature of this work…is based more on acquired intelligence, cognitive ability, relationship skills, and discretionary effort.”

Example of Technical Writing

![]()

There are many ways to successfully accomplish the result I want.

![]()

To get a better understanding of what this means, look at the example of technical writing. If you were to identify the very best technical writers in your organization and then assess how each one managed to write so effectively, you'd probably discover that each writer had a different approach. One writer used extensive outlines and did amazing amounts of advance planning and detailing. Another relied on time pressure and waited until the last possible moment to begin writing. A third wrote best in a group setting with lots of conversation and give-and-take from contributors so the final result was absolutely a team-produced effort. A fourth was more of a lateral thinker and would brainstorm ideas on Post-it notes on a wall and then form a coherent sequence. Perhaps you most identify with one of these approaches, or you have yet another way of writing.

What this illustrates is how several people can do an outstanding job of writing a clear, accurate, and persuasive analysis in several different yet effective ways. This is because good technical writing requires much thinking, internal decision making, and individual thought. To phrase this one other way, technical writing can be done successfully in a number of ways, and different individuals can end up with the same successful product with different approaches and steps.

Critical Implications

One critical implication of this is to avoid fixating on exactly how employees must behave because this is not the key element—the accomplishment is. Another is that to work well, employees likely will need to be flexible in how they work. As Pepitone (2000, 141) notes, “Worker discretion is precisely the way knowledge and service workers achieve effectiveness.” This is a crucial point because it involves a sea change in what organizations typically focus on in managing employees. And although workforces and the nature of work around the globe have now been evolving for decades (to more of a knowledge-worker model—even assembly lines now require more decision making), management approaches have often failed to keep up with this evolution.

Learning from the Importance of Accomplishments

In many organizations, there is a tremendous amount of internal measurement and data collection about employees and their performance. The popularity of 360-degree assessments as a performance management tool can result in much feedback for each performer. Although performance reviews and annual evaluations are almost universally dreaded (and some organizations implement them inconsistently), the majority do use them. Organizations may track customer feedback about particular employees, note disciplinary actions and letters of reprimand, or track feedback from work on specific projects. Generally, a great deal of measurement in organizations purports to focus on employees' performance. But just because something is being measured doesn't mean it's worth measuring—especially when evaluating performance and people.

![]()

Don't rate potential over performance.

![]()

When it comes to performance, many organizations focus on and measure the wrong things. One particular industry is cataloged brilliantly in Michael Lewis's (2003) book Moneyball, which looks at professional baseball teams. More specifically, Lewis examined the question of how rich teams like the New York Yankees could spend $126 million in player payroll while the Oakland Athletics could spend only $40 million and yet end up with similar success. Lewis looked at the As' general manager, Billy Beane.

According to Beane, most baseball teams are built by focusing on the wrong things. Baseball scouts and talent evaluators have often emphasized behavior or, more specifically, appearance. Scouts can talk about how some player has the right “body” or carries himself like a major league ball player. Lewis, writing about Beane's approach to picking performers notes, that “a young player is not what he looks like or what he might become but what he has done. As elementary as that might sound to someone who knew nothing about professional baseball, it counts as heresy here. The scouts even have a catch phrase for what Billy [Beane] and Paul [DePodesta, the assistant general manager] are up to: performance scouting. Performance scouting in scouting circles is an insult. It directly contradicts the baseball man's view that a young player is what you can see him doing in your mind's eye. It argues that most of what's important about a baseball player, maybe even including his character, can be found in his statistics” (Lewis 2003, 38).

Although this example is specific to baseball, it applies equally to almost all organizations and managers today. Managers too often focus on behavior, on intelligence, and on attributes, and they treat these as what the organization values most, when in reality it's the accomplishments that are critical and require their initial and primary focus. An organization cannot be consistently good at getting results if it fails to focus on the results for which employees are responsible.

![]()

An acre of performance is worth a whole world of promise.

![]()

Accomplishments are measurable and can be counted. Behavior, on the other hand, is often very subjective (Gilbert 1978). The service associate smiled when she greeted the customer, but was it a friendly smile? When the tech representative was troubleshooting the hard-drive crash, he was listening—but did it come off as insincere? It's tricky to measure how many times someone smiled or if they intended it to be sincere.

On the other hand, it's not that difficult to assess if customers felt welcomed or listened to. It's almost always easier to measure accomplishments than to measure behavior. And measuring accomplishments is almost always more objective and fairer, while measuring behavior is almost always more subjective. Although these points may seem very self-evident, they're about using evidence and data to make decisions rather than operating on biases, hunches, rules of thumb, and assumptions.

Part of the reason there are so many quotations from athletic coaches and managers in this section of the book is that the nature of a game is to have a winner and a loser—and thus, at least on a team level, performance results are usually very obvious. And although plenty of teams and managers still focus mostly on behavior, the most successful ones are ruthlessly clear about the difference between potential and effort and between behavior and the final score or the team's performance.

Accomplishments and Performance Gaps

Managers look at what they call performance gaps all the time. You probably hear phrases at work like “John needs to do a better job answering customer objections” and “Joan has to improve her negotiation skills.” But these really aren't about performance gaps. A performance gap must be able to be phrased in terms of accomplishments. Stating performance in terms of accomplishments means that, likewise, the gap is expressed by results—the gap between where we are versus where we need to be. It's not a statement about how people behave and how they need to behave faster or better. It's a statement about a result.

Thus, instead of “John needs to do a better job answering customer objections,” which is pretty subjective, it's better and more useful to say “John has a sales closing rate of 20 percent, and it needs to be 40 percent.” The performance gap in this case is the difference between the actual accomplishment and the target results. Answering objections isn't the performance gap; it's the behavior that must change if John is going to close this gap.

Behavior's Relevance for Accomplishments

This focus on accomplishments does not mean that behavior is irrelevant. Again, behavior does matter, but not as the end the organization seeks or the result it values. Think of behavior as a series of tasks that an employee does to achieve a particular accomplishment. A smart organization first focuses on accomplishments. If a performer is exemplary and generates outstanding results, then it makes sense to look at what that person does to learn how other employees can also do it. Does she add a step? What is it that she does that makes her so good?

At the same time, when employees underperform, then once the performance gap is clear (so there is a measure of what things need to change to achieve results), it's valuable to look at tasks to see what the underperformer is doing wrong or not doing. This process of first starting with the result or accomplishment and only then looking at the behavior is not only a way of maintaining focus on the right priority. It's also a way of adjusting to individual differences in performance and recognizing that what you do to get a result may not be the same thing that others—who are equally effective—do.

![]()

When I evaluate players, I first look at what they accomplish in their role on the field. There is lots of pretty play that produces nothing, lots of talented individuals that fail the team. There will be a place to look at individual skills and aptitude, but first I want to know if they can perform.

![]()

Why does this approach conflict with the way that managers currently operate (by focusing on how employees behave)? Why can't looking at behavior generate good performance? Don't both approaches ultimately end up in the same place—by looking at behavior? When managers focus first on the behavior, they become guilty of equating the behavior with the desired outcome or result. Those two (the behavior and the accomplishment) are not the same. To start by focusing on behavior allows the manager to be misled. Emphasizing the behavior (whether it's what people do, what they know or their attitudes) makes it nearly impossible for the manager to distinguish between what behavior is critical to the result versus which behavior is just desired or a function of the manager's bias (that is, the way the manager was taught to do that job).

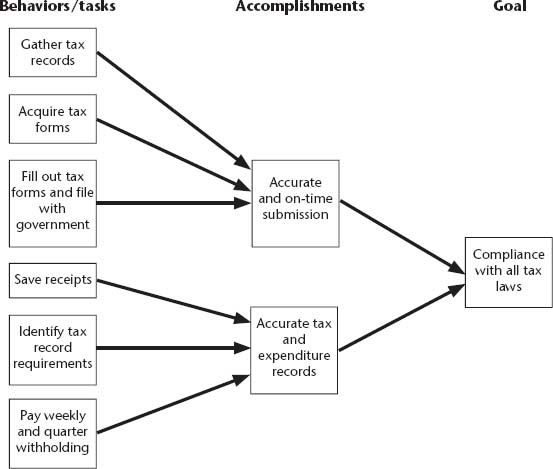

Figure 4–1 illustrates the relationships between behaviors/tasks, accomplishments, and the results of performance. The figure looks at the simple example of meeting the goal of “compliance with tax requirements.” How to achieve this goal involves a number of accomplishments with behaviors (or tasks) that occur in order to produce each accomplishment. In the figure, for brevity's sake, some behaviors have been combined or simplified—one can only dream that filling out taxes was so simple!

Figure 4–1. An Example of the Relationship of Behavior to Accomplishments and Results: Meeting the Goal of Compliance with Tax Requirements

Performance Solutions Notebook

![]()

Health-care-acquired infections (HAIs) are a good example of how executives focus on wrong elements of a problem while neglecting critical performance measures. The measurement of HAIs and the availability of data have often been issues. Some health care facilities have not felt the need to focus on measuring infection rates, arguing that conscientious and caring staff would be good enough to deal with the problem. Some have even argued initially that because of their level of expertise and commitment to healing, it would be condescending to imply that medical caregivers were causing harm (Gawande 2007).

However, this ignores the reality that performance problems don't have to be deliberate and can involve unintentional and competent individuals. Asking highly trained medical professionals to self-monitor isn't enough, because it's easy for behavior to inadvertently change just enough to affect results. “Behavior can become so automatic in healthcare you don't notice yourself slipping across that very thin margin of error” (Brennan 2006, 7). Specifically, with HAIs, this can mean that practitioners who forget to wash their hands a couple of times between patients on a busy shift can subtly become a means of transferring infections. Or in some cases, it may mean that hand washing still occurs but is hurried and not as thorough as it needs to be. This is part of the reason why it's critical to measure accomplishments (of which HAI rates are one) rather than just look at behavior. As Terri Gingerich of HA noted, “Once you start measuring, you realize there is a big difference between what your perception of your performance is, and what your performance actually is” (Beaver 2007). Gathering infection rate data and comparing it across facilities can serve as a useful means for identifying potential problems or examining against baseline numbers. Yet “one reason that the issue (HAIs) has been underreported until recently is that in most states, the rates of infections in hospitals are kept secret” (Dowling 2007). This is in part a function of an approach to performance issues that is often rooted in blame, scapegoating, and affixing responsibility for liability rather than improving performance (Goldman 2006). Although this potentially reduces possible liability risks, it makes it difficult for facilities or policymakers to identify those facilities or areas of practice with performance gaps, let alone improve their performance.

Hitting the Mark

![]()

Organizations need to focus on accomplishments, not behavior, to get results. As logical as this seems, very few organizations and managers clearly focus on the accomplishments or outcomes they expect from employees and instead focus on how people act and what they do. To focus on what really counts, draw on these key lessons from this chapter:

• Understand that focusing on behavior alone can be deceptive. Behavior can be faked, and it's hard to measure accurately. Furthermore, focusing on behavior implies that it is the ultimate result (rather than the outcome the behavior is supposed to produce). It's important for managers to avoid focusing on behavior or assuming that a particular behavior will produce particular results.

• Focus, instead, on accomplishments and results. Accomplishments, the work products that companies value in and of themselves, are the best means to understand and measure performance. For instance, a company wouldn't value politeness in an employee by itself, but polite behavior might indeed produce a happy customer (which the firm would value).

• Measure employee performance against accomplishments, not behavior. For modern work, especially in the service or information sectors, it is almost impossible to specify just one correct method or way to do the work. Such work almost always has multiple ways of producing the correct result, so a focus on accomplishments will be fairer and more appropriate.

Behavior does matter, but not as the primary means of evaluating performance or assessing productivity. Ultimately, behavior can provide clues to why accomplishments aren't being achieved. The next chapter looks at how to figure out what is causing the performance gap.