Chapter 7

Step 5: Learn from Your Best

![]()

Human beings, who are almost unique in having the ability to learn from the experience of others, are also remarkable for their apparent disinclination to do so.

![]()

Practically every executive pays lip service to the value of top employees. But from a performance standpoint, very few organizations realize how to leverage the talents of their best performers effectively, especially as catalysts to improve everyone's performance. In fact, many managers tend to penalize good employees—by dumping more work on them—and thus actually discourage good performance.

Most organizations take the view that the key to good performance is just to accumulate talented people. As earlier chapters have shown, this approach doesn't lead to better results because it ignores the importance of the organization for performance. In short, a bad process can easily overwhelm good people, and capable individuals don't operate in a vacuum—instead, their performance is shaped by organizational constraints (Rummler and Brache 1995).

What Makes an Employee Exemplary?

![]()

Each honest calling, each walk of life, has its own elite, its own aristocracy based on excellence of performance.

![]()

An exemplary or top performer is someone who consistently does a great job at something specific that the organization values. It's important to clarify this point. Ask most managers who their top performer is and they'd likely point you to someone who is perceived as being a good role model for others or someone who appears to be good at almost everything.

This chapter refers to an “exemplar” as someone who is very good at achieving a specific result or performing a distinct task. Being an exemplar does not mean being a model employee. It also does not mean that someone acts like the manager wants people to act. Nor does it mean that an exemplary performer is someone who is good at getting results but is a terrible person or an individual who walks over other people to get the best numbers. Exemplars are employees who are good at accomplishing at least one specific result and are good enough at this that they are potentially worth studying in attempt to apply lessons to the rest of the workforce. With a workforce that consists of a typical bell curve, exemplars are likely to fall into the upper 10 percent in accomplishments and/or results (with some exceptions, noted below).

One especially misleading belief is that someone can do their job well yet fail to be a good performer. Typically, this refers to a supposed star employee—like a leading salesperson or brilliant manager—who is also abusive to others or fails to work well on a team. It's a contradiction in terms to have someone who is achieving everything they're supposed to yet isn't living up to expectations or setting a bad example. It is indeed possible for someone to be an outstanding performer in one but not all aspects of their work—such as a salesperson who is an excellent closer but is poor with prospect follow-up.

But if someone is regarded as doing their job effectively, this should mean that the performer is very good at what the organization values. If management feels that someone is doing their job well yet is a poor performer—such as someone who pays strong attention to detail, so mistakes are low, yet also hits sales quotas while cutting corners—then the problem is that the organization has done a bad job defining what this employee is accountable for.

To put this another way, it's impossible for an employee to meet all of his or her standards yet be a poor employee—unless the organization has failed to define what constitutes good performance. Using the example given just above, if the organization wants sales that aren't unethical, the individual or unit goals need to be structured so they account for all elements that the business values.

It is possible for someone to be exemplary at just one element of the work. In fact, when an organization examines employees to identify the exemplary performers, it's possible that the true exemplars may not stand out. Consider a hypothetical example involving a sales representative. Generally speaking, a good salesperson should be strong at closing sales, identifying prospects, following up on sales to existing clients, and acquiring market knowledge. Each of these is a separate accomplishment; and in combination, they should result in many sales. It's also possible that someone could be very strong in one area yet so weak in others so his or her overall results aren't impressive.

How to Recognize and Leverage Exemplars

![]()

I think you can learn more from extraordinary groups than the run of the mill.

![]()

Exemplars are valuable because they can be studied to determine why others aren't as good or for ways to improve the performance of the rest of the workforce. Thus, it's possible that the true exemplars in a hypothetical sales force may consist of none of the top salespeople. But in examining performance details, someone in the middle of the pack may have a closing rate 30 percent higher than everyone else yet lag in total sales because of their inability to prospect, research, and provide good follow-up. Another salesperson may be superb at prospecting but not be able to close at all—thus hiding their results at prospecting.

Therefore, in looking for exemplary performers, it's important to remember two key points:

• No single employee may be outstanding in all elements of the work.

• Apparently ordinary workers, and even those perceived as poor performers, may actually be exemplary in some elements or subsets of their job in ways that could benefit the rest of the workforce.

![]()

timtowtdi—there's more than one way to do it.

![]()

Typically, most managers don't know who their exemplars are and also misunderstand the concept of an exemplary performer. Because so many organizations evaluate performance on the basis of behavior rather than accomplishments, if you go to most managers and ask who their best employee is, you'll probably be referred to the person who smiles the most, shows up on time, and never misses meetings. In short, there is a tendency to confuse the type of personality with the concept of an outstanding employee or top performer.

There is also a tendency to assume that all exemplars need to look alike. The reality is that several people doing the same work may approach it differently but each successfully. As Marcus Buckingham points out, “If you are clear about the outcome that you want, instead of standardizing the qualities and steps that you think are required to get to that outcome, you should honor that fact that [human] nature is irreducibly unique—rather than wasting time and money wishing that it weren't so” (quoted by LaBarre 2001). This complicates the process of studying and learning from exemplars because it's not enough to just copy successful people or to assume what works for one will work for all.

Even when organizations don't suffer from this confusion, they often fail to see the value in knowing if someone significantly outperforms the rest of the field. As a result, most organizations not only don't know who their best performers are; they're also likely to be misguided in what to even look for in determining excellence.

I had the opportunity to do consulting work for a call center. The client asked me to do two things: identify ways to reduce the wait time for customers phoning into the call center, and find a way to improve one employee's performance. This employee had a couple of performance issues, according to her managers. First, she was guilty of being too informal with callers. Rather than referring to customers using the titles “Mr.” or “Ms.,” she would call them “Honey” or “Dear.” Second, her average call lasted longer than those of her peers. Because the client wanted to reduce the amount of time callers spent on hold, they wanted employees with longer call times to reduce these averages. My client indicated that the particular employee who took too long was a sweet person, but they would have to dismiss her if she didn't improve.

This example highlights a common mistake organizations make in attempting to both assess performance and identify exemplars. The woman working for the call center who was in danger of being fired because of poor performance actually turned out to be the exemplar for her organization. Assessed by her behavior, she was a poor employee—she didn't follow protocol on how to address customers, and her calls lasted longer than those of her peers. But customer data showed her to be one of the people at the call center whom callers perceived as especially respectful and a strong listener. The clincher was that even though her average call took longer, she was more likely to resolve a problem during the first call—whereas customers talking with other call center representatives required an average of 2.8 calls before the problem could be put to bed.

This was a case of managers failing to recognize their real exemplar because they hadn't actually identified exactly what constituted good performance. They were thrown off by some of her behaviors (how she addressed customers and average call length), and they failed to focus on her accomplishments or the purpose of these behaviors (to ensure that customers felt respected and listened to, to efficiently solve the problem).

Not all organizations have top performers or exemplars. For instance, just because someone leads a firm in sales does not mean that this sales rep is an exemplar—the salesperson just happens to be better than the rest of the pack. And it's important to understand how these sales were achieved. If the salesperson got higher numbers by cherry-picking accounts, then there has been no exemplary performance.

Conversely, some truly elite organizations are full of outstanding performers that would exceed the upper 10 to 15 percent of the typical bell curve. Although a bell curve usually describes most organizations (with a few poor performers, a few outstanding performers, and the bulk falling in the middle), it doesn't describe all of them. Therefore, when identifying exemplars within a business, it's important to not assume that a normal bell curve applies. This also means, contrary to how it may seem, that the people with the best results aren't necessarily exemplars. And workers with apparently ordinary results may be exemplary at some specific roles or tasks.

How to Leverage the Value of Exemplars

![]()

Good management consists in showing average people how to do the work of superior people.

![]()

Generally speaking, most managers understand that having top performers on staff is a good thing. But most organizations don't realize the potential value that exemplary employees provide. First, the gap between the exemplary performers and the mass of ordinary performers is typically huge. The psychologist Dean Keith Simonton examined exemplary performers in several fields and concluded:

No matter where you look, the same story can be told, with only minor adjustments. Identify the 10 percent who have contributed the most to some endeavor, whether it be songs, poems, paintings, patents, articles, legislation, battles, films, designs or anything else. Count all the accomplishments that they have to their credit. Now tally the achievements of the remaining 90 percent who struggled in the same area of achievement. The first tally will equal or surpass the second tally. Period. (Pfeffer and Sutton 2006, 87)

Although the fields Simonton examined may seem a bit beyond the traditional work product of most employees, studies of more conventional types of work show similar performance gaps between exemplary performers and those in the middle of the pack. Pfeffer and Sutton noted that

a less dramatic but still large difference was uncovered by industrial psychologists Frank Schmidt and John Hunter, who analyzed all published studies spanning 85 years that measured or counted the amount of output for difference employees. They found in comparing superior workers (at the 84th percentile) with average workers (at the 50th percentile) that superior workers in jobs requiring low skill produced 19 percent more than average workers, superior workers in jobs requiring high skill were 32 percent more productive, and, for professionals and managers, superior performers produced 48 percent more output than average performers. (Pfeffer and Sutton 2006, 87)

Clearly, exemplary performers don't just do better than the rest of the workforce—they do dramatically better. The traditional response for most organizations has been to try to hire many top performers based on the assumption that having a lot of talented individuals will result in a strong organization. As noted above, the assumptions embedded in this approach are wrong.

Another variation has been for management to focus primarily on the best performers, trying to keep them happy while letting the rest of the workforce mostly take care of themselves. But the real value of exemplars is not just in the outstanding performance that they deliver to the organization; it's that these accomplished performers can provide practical ideas for how to boost the performance of everyone else in the organization. Analyzing the performance of exemplars thus can provide insight into the causes of performance gaps. And it also can reveal shortcuts for boosting results more effectively than most strategies organizations try.

This process of using exemplars to improve the performance of other employees can be easily misused. The key is understanding what exactly the exemplar is doing that contributes to his or her outstanding performance. It's not enough to just copy what the exemplar is doing—because some of what the exemplar does may not provide value.

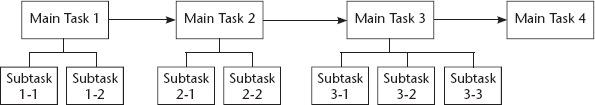

This ability to distinguish between the critical versus the trivial is a function of an effective task analysis as well as a good understanding of how the job functions. To be sure that you don't gloss over critical steps within a job when doing a task analysis, look for ways to capture all the details. Figure 7–1 shows what a diagram of part of a task analysis would look like. (See chapter 5 for more on task analysis.) And it's also important to recognize that as jobs increasingly require discretion and thus defeat efforts at standardization, just taking what one successful performer does and requiring everyone else to mimic that performer is not likely to be as effective.

Figure 7–1. Example of Part of a Task Analysis

How Exemplars Differ from Other Employees

Of course, the initial way to identify top performers is through their accomplishments. But research into top performers shows nine things that they are likely to do differently from other employees and that can explain their outstanding performance (Fuller and Farrington 1999). All these things are not just ways that they become top performers—they are also ways of identifying exemplars. Thus, someone interested in spotting the exemplars in an organization can look for these nine indicators:

• Eliminates steps.

• Adds an extra step.

• Takes advantage of available information.

• Creates job support aids.

• Possesses information others don't have.

• Accesses better tools.

• Has a different motive.

• Gets better guidance.

• Gets different incentives.

Of course, these indicators vary from exemplar to exemplar and in particular situations. To take just the first two indicators above, obviously not all employees who eliminate or add extra steps are exemplars. But looking for these indicators is a quick-and-dirty way to spot employees who are doing things differently, which makes them potential candidates for exemplary performance. The ultimate criterion for whether someone is an exemplar of course will be their accomplishments. That said, let's look briefly at each of the nine indicators.

Eliminating Steps

Top performers find ways to shorten processes or stop doing things that don't give value added. Too often, the “official” way of doing things involves tasks that aren't necessary. Exemplars discover quicker or better ways of doing things. Often, this elimination of steps occurs without official approval. This is an important insight, because sometimes a top performer may have to behave differently (by using the official process) when management is around and then use the more efficient method the rest of the time. This can make it difficult to identify what non-value-adding steps are being eliminated because the revised process ends up being undercover.

Adding an Extra Step

Exemplars often do an additional task that gives them a competitive edge or sets them apart from the competition. This task might entail something like adding extra material to a sales package or doing additional prep work before delivering a product to a client. This is usually a case of taking initiative and doing what makes sense, even when the company doesn't specify it. In these instances, instead of just doing their job, the exemplars are focusing on how to excel or perform as well as they can. Service-based organizations famously look for extra measures that will provide a competitive edge (such as a hotel doing turndown service and putting a chocolate on the pillow).

Taking Advantage of Available Information

Most information within organizations is rarely utilized, or employees don't even know it exists. Why? Because most people are too busy doing their job or don't think it's necessary to seek additional data. But a top performer often roots around for data or searches for more information than the briefings and reports that management already provides.

For instance, a top-performing manager might read through exit interviews or retention reports that are available to everyone but are generally ignored. A top-notch mechanic might comb through the past six months' worth of breakdown reports to identify trends and improve predictive ability on what parts are more likely to be defective. In part, this happens because of curiosity—an outstanding performer may be dissatisfied in not having a complete picture of how things work or why some results occur. Sometimes this is also a function of a top performer understanding the potential implications of the data and how it may be used—while others don't see the value in it.

Creating Job Support Aids

Workers with high standards don't wait for the business to give them what they need. They often develop job aids to help them remember or reduce the chance of error (so they get the right sequence, for instance). These memory aids may be rough or impromptu, yet they are usually very effective and tend to demonstrate the exemplar's unwillingness to wait for the larger organization to provide a solution when individual action can provide an answer. Self-generated job aids also reflect the exemplar's ability to problem solve at work and come up with solutions to bridge issues that otherwise tend to fall between the cracks of standard work processes.

Possessing Information Others Don't Have

Exemplars may analyze data—and thus gain additional insights—that the rest of the organization sees little value in even gathering. Often, this may involve information outside the organization's official resources (such as trade association reports or competitors' reports). Exemplars may establish their own information networks—not to exclude others, but because they feel the existing information they get is inadequate. For instance, they may spend extra time asking customers questions in their desire to understand the intricacy of a problem. They may follow up after a project ends to identify lessons learned when everyone else is too busy with new work. This quest for information may also involve going outside their work unit to talk with others in the organization to get a different perspective or see the big picture.

Accessing Better Tools

Exemplars often bring in or purchase better tools than what their company provides. It's not uncommon to see exemplars with upgraded versions of software, more precise instruments, or equipment with higher ratings that they bought with their own money. Usually this is because these exemplars are intolerant of the less capable company-issued equipment. In some cases, exemplars may insist on more precision because they pay more attention to detail. Exemplars may also adapt existing tools to perform better on the job.

Having a Different Motive

Top performers tend to have internal motives that may differ dramatically from those of the rest of the workforce. Whether it's a desire to get promoted, competitive fire, fear of failure, or something unique to their makeup, the best performers typically have their own reasons for paying greater attention to detail or caring more about the results more than their peers.

Getting Better Guidance

Some top performers work for managers who do a better job coaching. These managers provide feedback and encouragement that lead to better performance. In short, some people excel over their peers because they end up working for better managers. An additional factor here is that top performers often interact with managers in ways that encourage more or better guidance. These performers may seek extra feedback from managers, ask more questions, or interact with managers in ways that encourage better coaching.

Getting Different Incentives

In large organizations, there are tremendous disparities in what gets rewarded and how. Incentives don't have to consist entirely of tangible rewards—some could involve appeals to pride or self-esteem. Some performers are fortunate enough to get managers who are skilled at using rewards and recognition to bring out the best in people. Also, the nature of many organizations can mean that two workers are doing the same job yet receiving different benefits (such as government versus trust fund employees, or tenured versus probationary workers). Thus, it's actually quite common to have people doing the same work yet being rewarded differently.

![]()

Excellence is a better teacher than mediocrity. The lessons of the ordinary are everywhere. Truly profound and original insights are to be found only in studying the exemplary.

![]()

Anders Ericsson is one of the leaders in the study of expert performers. He has spent decades studying what makes some people outstanding in their work. He provides a particularly illuminating example of exemplary tactics being applied:

Here's a typical example [of an exemplar]. Medical diagnosticians see a patient once or twice, make an assessment in an effort to solve a particularly difficult case, and then they move on. They may never see him or her again. I recently interviewed a highly successful diagnostician who works very differently. He spends a lot of his own time checking up on his patients, taking extensive notes on what he's thinking at the time of diagnosis, and checking back to see how accurate he is. This extra step he created gives him a significant advantage compared with his peers. It lets him better understand how and when he's improving. In general, elite performers utilize some technique that typically isn't well known or widely practiced [by their peers]. (quoted by Collier 2006)

The technique that isn't well known or widely practiced could be any one of the nine identified by Fuller and Farrington. In the instance cited here by Ericsson, it involves adding an extra step. The technique that isn't widely known is not because exemplars are typically secretive—it's rare for a top performer to refuse to share work insights. Instead, it's more likely to be a function of people who work concurrently but don't have an opportunity to observe their peers—or of employees who don't assume there is much value in observing others. And often the exemplar just assumes that the approach being used is so obvious that everyone else must have thought of it as well.

Encouraging Exemplars to Flourish

The typical response of most organizations once they identify the degree to which exemplars outperform the rest of their workforce is to focus on retaining or hiring more outstanding performers. As noted in earlier chapters, however, this approach generally fails. First, organizations typically do a bad job of identifying what is an exemplar and what makes that employee so outstanding. So when the organization seeks to hire away elite performers from other companies, managers are often focusing on the wrong factors. This is a particular problem when managers are focusing on behavior rather than performance to determine who is elite.

The environment also helps to produce the outstanding performer—so someone who is great at company X may not be able to produce the same results when hired at company Z. Managers need to recognize that good performance is much more than just collecting talented people.

There are also tremendous misperceptions about talent and performance. When it comes to talent and ability, most people tend to assume that some people are “naturals” or are blessed with a particular skill or aptitude. This assumption has critical implications for understanding exemplars as well as how organizations and even society go about developing people's skills and abilities. It drives temperament tests used in personnel selection, it serves as a fundamental principle for many educational systems, it helps to determine who ends up in what career track or is eligible for particular lines of work, and it influences how management assesses performers. This basic idea that some people have specific natural gifts that predispose them to be more successful than others is embedded in much of our society (Collier 2006).

In contradiction of this assumption, however, analyses of a number of different professions is now coalescing to form some very clear conclusions about outstanding performers. There is no such thing as a targeted natural talent—people are not predisposed with certain gifts or abilities that enable them to be more successful. It's true that some individuals may be more intelligent, more motivated, or have personality traits that give them potential advantages. But none of these elements (personality, intelligence, or motivation) would constitute natural talent, and in fact motivation may often be used by an apparently less-talented individual to surpass others who appear to have more ability. The idea that some individuals were born to be good at something is wrong.

The idea that there are no natural gifts is an important one for analyzing outstanding performers in the workplace. First, it means that it is a mistake to attribute success to something that is natural to that worker. If an exemplar appears to be a natural at something or a particular task comes easily to that individual, it's because they worked at it. Second, when a performer attributes success to individual talent—as in “I guess I was just born to do this”—it's a misperception that probably reflects the exemplar's inability to explain the performance.

This inability to understand what contributes to elite performance also helps explain why so many organizations bungle efforts to produce better results. Ericsson, probably the world's leading researcher on how experts and geniuses develop, notes that “the traditional assumption is that people come into a professional domain, have similar experience and the only thing that's different is their innate abilities. There's little evidence to support this. With the exception of some sports, no characteristic of the brain or body constrains an individual from reaching an expert level” (quoted by Collier 2006).

Research into outstanding performers and geniuses has looked into how they develop. It's not because of talent or innate ability. Instead, outstanding performers are made. More specifically, besides the environmental factors within the organization that influence people's ability to do great work (such as management support, resources, access to information, and appropriate resources), outstanding performers practice their trade—over and over and over. Those individuals—and this includes so-called child prodigies, such as Tiger Woods, Bobby Fischer, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart—who turn out to be incredible performers at the highest levels are those who practice longer and harder than their peers.

But it's not enough to just practice at something—whether it's facilitating meetings, developing a project timeline, composing music, driving a golf ball, or making financial projections. The type of practice is important. Ericsson and others have identified an approach to practice and work that allows performers to continue to strengthen their abilities while their peers stagnate. According to Ericsson, “Elite performers engage in what we call deliberate practice—an effortful activity designed to improve individual target performance” (quoted by Collier 2006).

Deliberate practice is work that is designed to intentionally improve one's ability by using specific goals that are modestly above one's current performance levels. Examples of deliberate practice might include the following:

• A technical writer might try responding to an imaginary proposal as a way of improving writing style and clarity.

• An exemplary technical writer would do the same activity but set a target of writing a scope-of-work response that is responsive to the work request but 20 percent shorter (and thus more concise) than the previous proposal.

• An outstanding project manager might set a personal growth goal for the next project of reducing total meeting time for all personnel by 15 percent—even if it's not expected as part of the project.

As Geoffrey Colvin (2006) notes, “The evidence, scientific as well as anecdotal, seems overwhelmingly in favor of deliberate practice as the source of great performance.”

Of course, the other aspect to point out about all these examples is how rarely most white-collar professionals actually practice anything other than PowerPoint presentations. This is ironic, because most business skills can easily be practiced (Colvin 2006). Even wisdom can be acquired—the rationale for using case studies and simulations is to improve decision making and insight. So a key point for employees is that becoming a top performer isn't just about working hard but also about practicing. Elite performers, however, not only take a deliberate practice approach but also practice consistently. Without consistent repetition to work on improvement, it's no wonder that many organizations produce genuine exemplars haphazardly.

The irony is that given the existing knowledge about exemplary performers, organizations should be able to consistently develop employees to very high levels of performance. But instead, it's easier for individuals and managers to believe that good performance comes from gifted people. As Colvin (2006) observes, “We are not hostage to some naturally granted level of talent. We can make ourselves what we will…. People hate abandoning the notion that they would coast to fame and riches if they found their talent. But that view is tragically constraining because when they hit life's inevitable bumps in the road, they conclude they just aren't gifted and give up.”

Organizations interested in getting more exemplary employees need to change their approach. It's not about hiring more talent. Only by gaining an understanding of what an exemplar is and how an employee becomes one will organizations be able to consistently and intentionally develop their employees so that the numbers of top performers grow dramatically.

![]() Performance Solution Notebook

Performance Solution Notebook

![]()

Through the 1980s and into the 1990s, health care organizations, much like many other American organizations, have been going through a sort of new management “fad of the week.” But trying to change a complex system from above carries with it great difficulties.

![]()

The concept of learning from exemplary performers has particular application for the problem of health-care-acquired infections (HAIs). Many health care organizations have instituted programs to address infections, yet the HAI rate varies tremendously from facility to facility. What accounts for the successes? Looking at exemplary performers (whether individuals, units, or entire facilities) can provide some insight for organizations still struggling to lower HAI rates. And learning from accomplished performers can be both a faster way of implementing change and also less fraught with resistance issues, because the initiative has a chance of being seen as organic rather than coming from the outside.

A more common problem for HAI programs has been the sustainability of results. “Traditional educational hand-hygiene programs comprise in-services, behavioral modification/intervention and observation components. Experts say that while these methods trigger initial success and improvement [in lower HAI rates], they are short-lived” (Pyrek 2006). Copying from other organizations without understanding the nature of their success can lead to results like this. And examining organizations that show sustained success in lowering HAI rates can provide insight into why so many facilities see only short-term positive effects in the fight against HAIs.

In addition, smart organizations realize that sometimes the exemplary example resides not only outside their organization but even outside their industry. Too often, a not-invented-here syndrome prevents organizations from learning from top performers in other fields. Yet it's often possible to find top performers in unexpected places. As one doctor concluded when looking at HAI issues, “Another industry in which cleanliness is paramount—computer-chip manufacturing—may be able to teach us [in the health care field] something about this issue” (Goldman 2006, 122).

Hitting the Mark

![]()

A number of lessons can be gained from this chapter:

• The fastest way to improve performance and reduce gaps is by identifying the exemplars or accomplished performers. Outstanding performers can provide clues for quick ways to improve performance.

• You can then use the lessons learned from the exemplars to improve the overall work quality of the rest of the workforce. Even if the majority of employees (the largest part of the bell curve—typically 60 to 80 percent of staff) never reach the level of your best people, if that many employees boost performance by 5 to 10 percent due to insights gained from studying the exemplars, then the company will see tremendous improvements across the board.

• Most managers do a poor job of defining and identifying exemplary performers. Remember, someone is an exemplar based on accomplishments, not behavioral traits, intelligence, or congeniality.

• Exemplary performance may be hidden. You may have an apparently average worker who is extraordinary at some tasks. Rather than look for just superstars, identify critical tasks and then measure to see who consistently gets great results doing that work.

Learning from exemplary performers is one of the best ways to improve performance in an organization. These exemplars make it possible to clarify performance gaps numerically, and they provide insights on how to boost performance. Yet most businesses happen to do poorly at leveraging exemplars to enable them to understand and improve results. The next chapter looks at the importance of information. Ironically, at a time when most organizations are drowning in data (if you doubt this, just check your email inbox), most employees are starved for the information they need to perform effectively.