Chapter 4

![]()

Amount (The Antideficiency Act)

Having covered purpose and time in the preceding two chapters, we come to the final tenet of appropriations law—amount. It is with this aspect of fiscal law that Congress exercises its ultimate control through the Antideficiency Act. Although purpose and time violations are in conflict with federal law, they carry no specific penalties and are often correctable without consequences to the agency or its personnel. However, when purpose or time violations result in an “amount” violation, or the agency creates an “amount” violation on its own, the Antideficiency Act comes into play. Penalties for violation of the Act can be severe. It is through the possibility of sanctions under the Antideficiency Act that Congress can fully exercise its power of the purse.

Before discussing the Antideficiency Act in detail, it is first necessary to lay the groundwork for its discussion by examining the relationship between an agency’s budget submission and its actual budget execution, the significance of congressional committee reports, lump sum versus line item appropriations, and how earmarks are handled.

BUDGET SUBMISSION VERSUS BUDGET EXECUTION

143. Congress appropriates budget authority largely based on the budgets submitted by agencies. Must agencies execute the appropriations provided by Congress exactly as proposed in their budgets?

Any restrictions on the use of an appropriation contained in an agency budget or in congressional committee reports are not legally binding on the agency unless specified in the appropriations act itself.1 Congress recognizes that priorities change between when a budget is submitted and when an appropriation is received and executed.

Although budgets and legislative history in committee reports are not legally binding, in practice the agency must not show complete disregard for such restrictions. The appropriations process happens annually, and an agency that shows a lack of regard for oversight or appropriations committee recommendations will likely be called to task in the next budget cycle and find its next appropriation reduced or severely limited by line item restrictions.2

Agencies must walk a fine line. The best advice is to first and foremost comply with the law and any executive orders. Then make sure you have complied with agency regulations. Finally, if any flexibility remains, keep the committees concerned happy.

LUMP SUM VERSUS LINE ITEM APPROPRIATIONS AND EARMARKS

144. How are lump sum appropriations different from line item appropriations?

A lump sum appropriation is created to cover multiple programs, projects, activities, or items.3 A line item appropriation is available only for the specific object described in the appropriation.4 A form of line item appropriation is an earmark, which is simply a line item appropriation contained within a lump sum appropriation.5

An example of a lump sum appropriation is Salaries and Expenses, provided for “employees’ salaries and all necessary expenses of the agency.” Most every agency has one or more lump sum appropriations.

Less common are line item appropriations. An example would be an appropriation to construct a particular building. Another would be funding for a new financial management system.

Earmarks are the most common form of line item funding. Congress provides the agency with a lump sum appropriation but then specifies that a portion of that lump sum must be spent in a certain fashion on a particular object.

145. Isn’t Congress trying to eliminate earmarks?

There is strong political pressure to eliminate earmarks or, as a minimum, identify their source within the Congress. This is because of the negative reputation attributed to earmarks that pundits and many in the public call “pork barrel spending”—earmarks intended to benefit a particular segment of the economy, usually within a particular congressperson’s district or state.

But not all earmarks are of that nature. Many of them are simply a convenient way for Congress to make its wishes known on how it wants a particular program administered. They could just as easily be converted into stand-alone line item appropriations. These would have the same effect as an earmark without technically being an earmark.

146. Is there more than one kind of earmark?

There are three basic kinds, usually referred to as ceilings, floors, and fences. Let me illustrate with a hypothetical appropriation:

For the purchase of motor vehicles, $1,000,000, provided that not to exceed $100,000 shall be used for limousines, provided that not less than $200,000 shall be used for ambulances, and further provided that $300,000 is exclusively for pickup trucks.

The first earmark, for limousines, is called a ceiling, and it uses the phrase “not to exceed” (or sometimes “not more than”). The agency may spend any amount from $0 to $100,000 on limousines, but not a penny more. Any portion of the $100,000 not spent on limousines may be used in the general appropriation for other motor vehicles.

The second earmark, for ambulances, is called a floor, indicated by the phrase “not less than.” Congress inserts floors into appropriations when it fears the agency will not spend enough on a particular object that Congress believes needs more, rather than less, funding. The agency is free to spend any amount greater than $200,000, within the confines of the appropriation, on ambulances. If for some reason (say, ambulances are in short supply) the agency is unable to spend the entire $200,000 on ambulances, any amount under-executed needs to remain available as an unobligated balance within the appropriation and be allowed to expire. For example, if the agency can obligate only $150,000 on ambulances, the remaining $50,000 must not be obligated for any purpose, thus bringing the total available funding in the appropriation down to $950,000. The agency would need at least $50,000 as an unobligated balance when the appropriation expires.

The last earmark, for pickup trucks, is called a fence. It contains the aspects of both a ceiling and a floor. When Congress uses the term “exclusively for” or “shall be available only for,” it wants the agency to spend exactly that amount on the particular object—no more, no less. Thus, we say that $300,000 is “fenced off” from the rest of the appropriation.

147. Do violations of earmarks carry the same Antideficiency Act implications as violations of the entire appropriation?

They do. Earmarks are considered to be appropriations in their own right. Overspending a ceiling or a fence is a violation. Underspending a floor or a fence and then obligating the money for something else is a violation.

148. One last question on lump sum appropriations: May an agency “zero fund” a particular program?

So long as the program is not statutorily mandatory and is not the subject of specific appropriations language, the answer is “yes.” The agency must also be careful to spend the funds on some other authorized object to avoid the complications of impoundment.6

As previously mentioned, however, if the agency’s oversight or appropriations committee has expressed an interest in a particular program’s being funded, the agency, though not legally bound to support it through obligations, must be careful not to annoy the committee members.

ANTIDEFICIENCY ACT

149. The Antideficiency Act has been mentioned several times in preceding chapters. Can you summarize the basic requirements of the Antideficiency Act?

GAO issued a decision in 1962 (42 Comp. Gen. 272, 275) that summarizes the requirements in one paragraph:

These statutes evidence a plain intent on the part of the Congress to prohibit executive officers, unless otherwise authorized by law, from making contracts involving the Government in obligations for expenditures or liabilities beyond those contemplated and authorized for the period of availability of and within the amount of the appropriation under which they are made; to keep all the departments of the Government, in the matter of incurring obligations for expenditures, within the limits and purposes of appropriations annually provided for conducting their lawful function, and to prohibit any officer or employee of the Government from involving the Government in any contract or other obligation for the payment of money for any purpose, in advance of appropriations made for such purpose; and to restrict the use of annual appropriation to expenditures required for the service of the particular fiscal year for which they are made.7

This summary has often been quoted in subsequent Antideficiency Act cases.

150. Can you break the Antideficiency Act down into its individual elements?

GAO has broken it down as follows:8

The law prohibits:

![]() Making or authorizing an expenditure from, or creating or authorizing an obligation under, any appropriation or fund in excess of the amount available in the appropriation or fund unless authorized by law (31 U.S.C. 1341(a)(1)(A)).

Making or authorizing an expenditure from, or creating or authorizing an obligation under, any appropriation or fund in excess of the amount available in the appropriation or fund unless authorized by law (31 U.S.C. 1341(a)(1)(A)).

![]() Involving the government in any contract or other obligation for the payment of money for any purpose in advance of appropriations made for such purpose, unless the contract or obligation is authorized by law (31 U.S.C. 1341(a)(1)(B)).

Involving the government in any contract or other obligation for the payment of money for any purpose in advance of appropriations made for such purpose, unless the contract or obligation is authorized by law (31 U.S.C. 1341(a)(1)(B)).

![]() Accepting voluntary services for the United States, or employing personal services in excess of that authorized by law, except in cases of emergency involving the safety of human life or the protection of property (31 U.S.C. 1342).

Accepting voluntary services for the United States, or employing personal services in excess of that authorized by law, except in cases of emergency involving the safety of human life or the protection of property (31 U.S.C. 1342).

![]() Making obligations or expenditures in excess of an apportionment or reapportionment, or in excess of the amount permitted by agency regulations (31 U.S.C. 1517(a)).

Making obligations or expenditures in excess of an apportionment or reapportionment, or in excess of the amount permitted by agency regulations (31 U.S.C. 1517(a)).

Bear in mind that the basic principles are really quite simple: Government officials may not make payments or commit the United States to make payments at some future time for goods or services unless there is enough money in the appropriation or apportionment to cover the cost in full.

151. Don’t violations of the purpose law and the bona fide needs rule constitute violations of the Antideficiency Act?

Violations of the purpose law (31 U.S.C. 1301) and time restrictions, including the bona fide needs rule (31 U.S.C. 1502), might result in violations of the Antideficiency Act—or they might not. The Antideficiency Act is violated only when the amount in an appropriation or other subdivision of funds is breached. Although many Antideficiency Act violations are caused by purpose violations or time violations, not all purpose and time violations create Antideficiency Act violations. The relationship between purpose and time violations and the Antideficiency Act will be discussed in more detail later.

152. What is the key provision of the Antideficiency Act?

The central provision of the Antideficiency Act is 31 U.S.C. 1341(a)(1), which states:

(a)(1) An officer or employee of the United States Government or of the District of Columbia government may not—

(A) make or authorize an expenditure or obligation exceeding an amount available in an appropriation or fund for the expenditure or obligation; or

(B) involve either government in a contract or obligation for the payment of money before an appropriation is made unless authorized by law.

In the beginning, this was the only provision of the Antideficiency Act. Congress subsequently added other provisions to ensure compliance with this basic prohibition.9

153. Am I to understand that the Antideficiency Act can be violated at the time of obligation, not just when the payment becomes due?

That is correct. The act of obligating the United States to make a payment is a violation if sufficient budget authority is not already in the agency’s account.10

154. Section 1341 states that a violation occurs when funds are obligated or spent in excess or advance of an “appropriation or fund.” Can you describe what is meant by “appropriation or fund”?

The phrase refers to appropriation and fund accounts held by the Treasury. An appropriation account is the basic unit of an appropriation that reflects each unnumbered paragraph of an appropriations act. Fund accounts include general fund accounts, intragovernmental fund accounts, special fund accounts, and trust fund accounts. Revolving funds, such as working capital funds, are likewise prohibited from overobligating available budget authority or overdisbursing their fund balances with the Treasury.11

Not every transaction using federal funds constitutes an obligation or expenditure, however. For example, section 1341 applies to Indian trust funds managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. But when the Bureau invested some of those funds in certificates of deposit with federally insured banks (which was authorized by statute), GAO determined that investing is not obligating or expending. Thus, even the act of overinvesting such trust funds does not violate the Antideficiency Act unless or until such overinvested funds are actually obligated or expended by the Bureau.12

155. Is year-end the only time I need to worry about Antideficiency Act violations? How about end-of-quarter or end-of-month?

An Antideficiency Act violation can occur at any time, not just at the end of a fiscal period. Although the end of a year or quarter is when an agency is most vulnerable, because of the lapsing of appropriation or apportionment balances, care must be taken to avoid an overobligation at any moment in time.

156. If the obligations recorded in my accounting system exceed my appropriation, have I automatically violated the Antideficiency Act?

Section 1501 of Title 31 requires agencies to promptly and properly record all obligations. Therefore, recorded obligations in excess of the available appropriation are prima facie evidence of a violation of the Antideficiency Act. However, this is not conclusive evidence that a violation has occurred.13 Agencies often make mistakes. They sometimes record as obligations transactions that are not truly obligations. They might overstate the amount of the true obligation when recording it. They might record transactions as obligations before the obligation actually exists. In all of these situations, if review and adjustment of the accounting records shows that the level of actual obligations never exceeded the available appropriation, then no violation has occurred.

On the other hand, agencies often make mistakes in the opposite direction when recording obligations. They sometimes fail to record an obligation or do not record it in a timely manner. They also might under-record the amount of the obligation. Or they might record it to the wrong account. In these instances, although the accounting records might show an available balance, when the obligations are eventually posted correctly, they might reveal that a violation has occurred. Failing to record an obligation or improperly posting one does not relieve the agency’s responsibility to report all actual violations.14

The point here is that an obligation or expenditure posted in the accounting records merely evidences the obligation or disbursement; it doesn’t create it. Funds are obligated or expended by authorized officials, such as contracting officers and disbursing officers. They exist regardless of whether they are posted as such in the agency’s books.

Therefore, whenever a violation is suspected, a thorough understanding of what constitutes an obligation, and when it occurs, is necessary. Agency officials must be familiar with the provisions of 31 U.S.C. 1501. Chapter 7 of the Principles of Federal Appropriations Law should also be consulted for guidance.

Indemnification Agreements

157. What is an indemnification agreement?

Under an indemnification agreement, one party to the agreement—the government, for Antideficiency Act purposes—promises to cover another party’s losses. The federal government has very deep pockets, so it is not surprising that contractors and state or local governments frequently ask that their risk of loss be covered.15

158. An indemnification agreement somehow seems like an extension of the federal government’s policy of self-insurance. What is wrong with the government’s also insuring against contractors’ or other government entities’ losses when they are doing work for the federal government?

The problem is that if the amount of the government’s liability is indefinite, indeterminate, or potentially unlimited, the Antideficiency Act will be violated because appropriations are finite sums. The potential liability is greater than any appropriation ever passed. Therefore, both GAO and the courts have consistently ruled that without specific statutory authority the government may not enter into such an unlimited agreement and that doing so automatically constitutes a violation of the Antideficiency Act.16

Purpose and Time Violations versus Antideficiency Act

159. What is the relationship between the purpose law and the Antideficiency Act?

This section will cover how to determine when and to what extent a purpose violation also violates the Antideficiency Act. 63 Comp. Gen. 422, 424 (1984) offers a useful starting point for this discussion:

Not every violation of 31 USC 1301(a) also constitutes a violation of the Antideficiency Act…. Even though an expenditure may have been charged to an improper source, the Antideficiency Act’s prohibition against incurring obligations in excess or in advance of available appropriations is not also violated unless no other funds were available for that expenditure. Where, however, no other funds were authorized to be used for the purpose in question (or where those authorized were already obligated), both 31 USC 1301(a) and 1341(a) have been violated. In addition, we would consider an Antideficiency Act violation to have occurred where an expenditure was improperly charged and the appropriate fund source, although available at the time, was subsequently obligated, making readjustment of accounts impossible.17

160. Why does it matter whether an agency breaks one law or two laws?

It matters because Antideficiency Act violations carry statutory reporting requirements and potentially severe penalties. Purpose law violations often arise from simple mistakes in posting obligations and are easily fixed by reversing the problem transaction—so long as the Antideficiency Act has not also been violated at the same time.

161. Can you summarize that Comptroller General decision (63 Comp. Gen. 422, 424 (1984) regarding the applicability of the Antideficiency Act?

The gist of it is that a purpose law violation doesn’t automatically violate the Antideficiency Act, so long as it can be determined, once the correct appropriation is charged and the purpose law violation fixed, that sufficient proper budget authority was available at the time of the obligation and was continuously available ever since. In other words, if the original mistake of charging the wrong appropriation had not been made, and the correct appropriation had been charged, would the Antideficiency Act have been violated? If the answer is “no,” because there would have been no question about funding availability if the correct appropriation had been charged, then no Antideficiency Act violation exists.

Another way to look at it is that the Antideficiency Act applies to only the amount available for obligation or disbursement. Purpose law violations (and time or bona fide needs violations) often lead to Antideficiency Act violations but do not by themselves constitute Antideficiency Act violations.

162. Can you provide some examples of purpose and time violations and how it is determined that an Antideficiency Act violation has occurred?

Suppose an agency charges an obligation or disbursement to the wrong appropriation account, either charging the wrong appropriation for the correct time period or charging the wrong fiscal year. If the appropriation that should have been charged in the first place had sufficient funds and has continued to have sufficient funds, allowing for adjustment of the accounts, no Antideficiency Act violation has occurred.

A 1994 decision (73 Comp. Gen. 259) documents a case in which an agency erroneously charged some furniture to the wrong appropriation but had sufficient funds in the proper account to support an adjustment correcting the error. GAO concluded that no Antideficiency Act violation had occurred.

On the other hand, a violation exists if the proper account does not have enough money to permit the adjustment, including cases in which sufficient funds were available at the time of the error but were not continuously available until the time of correction. This finding is supported by 70 Comp. Gen. 592 (1991) and B-222048, February 10, 1987.18

Other relevant cases involved grant funds charged to the wrong fiscal year, contract modifications charged to expired accounts rather than to current appropriations, and items that should have been charged to other operating appropriations charged instead to the General Services Administration working capital fund.19

163. If Congress specifically prohibits the purchase of a certain commodity, could such a purchase trigger a violation?

Absolutely. Prohibitions come from several sources. Sometimes authorization acts or other general statutes contain language forbidding the purchase of certain items or services.

The Employment Standards Administration (ESA), Department of Labor, reported a violation in FY 2007 that illustrates this concept. Federal law prohibits federal agencies from paying an employee who is not a citizen of the United States and does not meet certain exceptions. ESA paid over $29,000 to an employee who was a Mexican citizen. This violated 31 U.S.C. 1341 because the amount available for payment to non-U.S. citizens is zero.20

GAO decisions are another source of prohibitions against the purchase of particular commodities. Examples include gifts to employees, reimbursement for commuting to work in a privately owned vehicle, and greeting cards.

Finally, appropriations acts typically contain many prohibitions. These usually contain language such as “None of the funds provided under this or any other act shall be used for ….” The FY 2008 Consolidated Appropriations Act contains a host of prohibitions against paying for particular commodities, including:21

![]() Construction or repair of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) vessels in foreign shipyards

Construction or repair of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) vessels in foreign shipyards

![]() Promoting the sale or export of tobacco products

Promoting the sale or export of tobacco products

![]() Issuing patents encompassing a human organism

Issuing patents encompassing a human organism

![]() Supporting the use of torture by any United States government official or contract employee

Supporting the use of torture by any United States government official or contract employee

![]() Purchasing first class or premium airline travel in contravention of Title 41 of the Code of Federal Regulations

Purchasing first class or premium airline travel in contravention of Title 41 of the Code of Federal Regulations

![]() Sending more than 50 employees from a federal department or agency to, or paying for their attendance at, any single conference occurring outside the United States.

Sending more than 50 employees from a federal department or agency to, or paying for their attendance at, any single conference occurring outside the United States.

In all of these situations, obligating or disbursing federal funds for prohibited or unauthorized goods or services constitutes a violation of the Antideficiency Act. The Comptroller General stated this principle very clearly in a 1981 decision:

When an appropriations act specifies that an agency’s appropriation is not available for a designated purpose, and the agency has no other funds available for that purpose, any officer of the agency who authorizes an obligation or expenditure of agency funds for that purpose violates the Antideficiency Act. Since the Congress has not appropriated funds for the designated purpose, the obligation may be viewed either as being in excess of the amount (zero) available for that purpose or as in advance of appropriations made for that purpose. In either case the Antideficiency Act is violated.22

Examples of violations where agencies ignored a statutory restriction abound:23

![]() Use of funds in violation of a statutory prohibition against publicity or propaganda

Use of funds in violation of a statutory prohibition against publicity or propaganda

![]() Appropriations used for unauthorized technical assistance

Appropriations used for unauthorized technical assistance

![]() Violation of an appropriation rider prohibiting the use of funds to implement an OMB memorandum

Violation of an appropriation rider prohibiting the use of funds to implement an OMB memorandum

![]() Appropriation used to procure unauthorized legal services

Appropriation used to procure unauthorized legal services

![]() Unauthorized use of a Training and Employment Services Account appropriation

Unauthorized use of a Training and Employment Services Account appropriation

![]() Violation of a “Buy American” provision in an appropriations act

Violation of a “Buy American” provision in an appropriations act

![]() Reprogramming of funds for an unauthorized purpose

Reprogramming of funds for an unauthorized purpose

![]() An employee detail (temporary work assignment) that is contrary to a specific statutory prohibition.

An employee detail (temporary work assignment) that is contrary to a specific statutory prohibition.

164. When an illegal contracting document is issued (for example, for bottled water) and payment is subsequently made, who is named in the Antideficiency Act violation report—the funds-authorizing and contracting officials or the certifying officer?

It is up to the agency to determine who the culprits are. Although the acts of certifying and disbursing created the Antideficiency Act violation, most agencies will cite the funds-authorizing official on the front end of the transaction as the person who caused the violation. Had the funds-authorizing official not approved the use of the funds for the item, the certifying officer would not have been put into the position of certifying the transaction for payment.

Further, funds-authorizing officials tend to be of a higher grade than certifying officers and are thus expected to “know better.” In addition, the certifying officers have pecuniary liability to worry about, which is not a concern of the funds-authorizing official.

Exceptions

165. Are there any exceptions to the Antideficiency Act?

There are several, all based in law. The Act itself recognizes that Congress may grant exceptions. Section 1341 of Title 31 prohibits obligations or expenditures in advance or excess of available appropriations “unless authorized by law.” This is a clear recognition that Congress may authorize exceptions to the laws it passes.24

166. Can you provide some examples of exceptions to the Antideficiency Act?

A major category of exceptions is broadly described as contract authority, which is defined as the statutory authority to enter into binding contracts without the funds adequate to make payments under them.25 Contract authority is one of several types of budget authority described in OMB Circular A-11.

The term contract authority as used in this context must not be confused with the “authority to enter into contracts.” An agency does not need specific authority to enter into contracts. This legal authority to enter into contracts does not constitute an exception to the Antideficiency Act. To constitute an exception to the Act, a contract authorized by law requires the authority to enter into such contract without regard to the availability of appropriations. This authority must be provided to an agency by statute.

167. What is the value of a contract that an agency can’t make payments against?

Contract authority is extremely valuable in certain situations. A common use is to finance the purchase of inventory through a revolving fund. The idea is that contract authority allows the revolving fund to contract for large amounts of inventory without tying up its fund balance. The inventory purchased may have long manufacturing times, sometimes years. Rather than encumber very limited revolving fund balances for an extended period, contract authority is granted by Congress to enter into contracts for such inventory. Ultimately, the liquidations of the obligations incurred are financed by the revolving fund through the sale of the inventory to the revolving fund customers.

168. Is contract authority ever provided to agencies funded by direct appropriations, and if so, doesn’t that limit Congress’ future flexibility to decide how to appropriate funds?

Congress provides contract authority to direct-funded agencies on occasion. Contract authority does necessitate a commitment on Congress’ part to follow through with a liquidating appropriation at a later date.

Apportionment

169. What is apportionment?

Apportionment is a process by which, as the name suggests, appropriated funds are distributed to agencies in portions over the period of availability. OMB apportions funds for executive branch agencies. Appropriations for the legislative branch, the judiciary, the District of Columbia, and the International Trade Commission are apportioned by officials having administrative control of those funds.26 The term apportionment is officially defined as follows:

The action by which [the apportioning official] distributes amounts available for obligation, including budgetary reserves established pursuant to law, in an appropriation or fund account. An apportionment divides amounts available for obligation by specific time periods (usually quarters), activities, projects, objects, or a combination thereof. The amounts so apportioned limit the amount of obligations that may be incurred. An apportionment may be further subdivided by an agency into allotments, suballotments, and allocations. In apportioning any account, some funds may be reserved to provide for contingencies or to effect savings made possible pursuant to the Antideficiency Act. Funds apportioned to establish a reserve must be proposed for deferral or recission pursuant to the Impoundment Control Act of 1974 (2 U.S.C. 681–688).

The apportionment process is intended to (1) prevent the obligation of amounts available within an appropriation or fund account in a manner that would require deficiency or supplemental appropriations and (2) achieve the most effective and economical use of amounts made available for obligation.27

170. Is an obligation or expenditure in advance of or in excess of an apportionment a violation of the Antideficiency Act?

Yes. Section 1517(a)(1) of Title 31 prohibits such obligations or expenditures. GAO stated in B290600, July 10, 2002:

The Antideficiency Act prohibits … the making or the authorizing of obligations or expenditures in advance of, or in excess of, available appropriations…. An agency may obligate an appropriation only after OMB has apportioned it to the agency.

171. Is obligating or expending funds in excess of an allotment, suballotment, allocation, or other administrative subdivision of funds an Antideficiency Act violation?

OMB Circular A-11 is the controlling regulation for allotments and suballotments. It states that overobligation or overexpenditure of allotments or suballotments is always a violation.

Overobligation or overexpenditure of other administrative subdivisions is a violation only if an agency’s fund control regulations define them as such.28 OMB’s guidance is consistent with the language found in 31 U.S.C. 1517(a)(2) and 1514(a).

Voluntary Services

172. What does the Voluntary Services section of the Antideficiency Act say?

Section 1342 of Title 31 reads:

An officer or employee of the United States Government or of the District of Columbia government may not accept voluntary services for either government or employ personal services exceeding that authorized by law except for emergencies involving the safety of human life or the protection of property ….

173. Does the Voluntary Services prohibition tie in with the prohibition against augmentation?

Indeed it does. An objective of the Antideficiency Act was to keep an agency’s level of operations within the amounts Congress appropriates for that purpose. The use of voluntary services would permit circumvention of that objective because such a practice augments an appropriation.29 Funds not paid for such voluntary services are then available for other purposes. Receiving voluntary services is tantamount to receiving additional budget authority. Congress jealously guards its power of the purse and prohibits such external funding sources.

174. Are agencies also prohibited from accepting voluntary services from sources other than government employees?

The general answer is “yes.” Agencies should not accept the services of outsiders to accomplish tasks that should be done by government employees.30 Accepting outside services is another example of augmentation of an appropriation. However, a 1913 attorney general opinion made a distinction between voluntary services and gratuitous services. Only voluntary services are prohibited.

175. What is the difference between voluntary services and gratuitous services?

A 1913 attorney general opinion addressed whether a retired army officer could be employed as superintendent of an Indian school without additional compensation. The attorney general replied that the appointment would not violate the voluntary services prohibition of section 1342. The attorney general’s opinion discusses the distinction between the two terms:

[I]t seems plain that the words “voluntary service” were not intended to be synonymous with “gratuitous service” and were not intended to cover services rendered in an official capacity under regular appointment to an office otherwise permitted by law to be non-salaried. In their ordinary and normal meaning these words refer to service intruded by a private person as a “volunteer” and not rendered pursuant to any prior contract or obligation…. It would be stretching the language a good deal to extend it so far as to prohibit official services without compensation in those instances in which Congress has not required even a minimum salary for the office.

The context corroborates the view that the ordinary meaning of “voluntary services” was intended. The very next words “or employ personal services in excess of that authorized by law” deal with contractual services, thus making a balance between “acceptance” of “voluntary service” (i.e., the cases where there is no prior contract) and “employment” of “personal service” (i.e., the cases where there is such prior contract, though unauthorized by law).

Thus it is evident that the evil at which Congress was aiming was not appointment or employment for authorized services without compensation, but the acceptance of unauthorized services not intended or agreed to be gratuitous and therefore likely to afford a basis for a future claim upon Congress….31

The comptroller of the Treasury agreed with the attorney general’s interpretation. The comptroller, and subsequently GAO and the Justice Department, adopted this position and continue to follow it. The comptroller wrote:

[The statute] was intended to guard against claims for compensation. A service offered clearly and distinctly as gratuitous with a proper record made of that fact does not violate this statute against acceptance of voluntary service. An appointment to serve without compensation which is accepted and properly recorded is not a violation of [31 USC 1342], and is valid if otherwise lawful.32

Two main rules govern voluntary and gratuitous services. First, if compensation for a position is fixed by law, an appointee may not agree to serve without compensation or to waive that compensation in whole or in part. Actually, this portion of the opinion was not really new. The courts had already held that compensation fixed by law could not be waived. Second, if the level of compensation is discretionary, or if the relevant statute prescribes only a maximum but not a minimum, the compensation may be set at zero, and an appointment without compensation or a waiver, entire or partial, is permissible.33

176. Don’t some agencies routinely violate 31 U.S.C. 1342 by allowing employees to work extra hours without providing overtime pay or compensatory time off?

Most likely. Employees who are covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)—non–exempt employees—are entitled to payment for extra hours worked, or they may agree to accept compensatory time in lieu of payment. Federal managers must be very careful not to direct such employees to work overtime without compensation. They must be equally careful not to “suffer or permit” to work overtime eager non-exempt employees who are just trying to do a good job. The law is clear: Accepting such voluntary services constitutes a violation of the Antideficiency Act.

177. Has anyone ever actually reported a violation of 31 U.S.C. 1342?

Such a case was reported in 2005. U.S. Army National Guard civilians had worked on a weekend, without compensation, to deliver training to National Guard members.34

THE PROHIBITION OF AUGMENTATION

178. What is the rationale for the rule against augmentation of an agency’s appropriations?

The objective of the rule against augmentation of appropriations is to prevent an agency from undercutting congressional power by circuitously exceeding the amount Congress has appropriated for that activity. A recent decision (B-300248, January 15, 2004) put it this way:

When Congress establishes a new program or activity, it also must decide how to finance it. Typically it does this by appropriating funds from the U.S. Treasury. In addition to providing necessary funds, a congressional appropriation establishes a maximum authorized program level, meaning that an agency cannot, absent statutory authorization, operate beyond the level that can be paid for by its appropriations. An agency may not circumvent these limitations by augmenting its appropriations from sources outside the government. One of the objectives of these limitations is to prevent agencies from avoiding or usurping Congress’ “power of the purse.”35

179. Is there a specific statute forbidding augmentation?

There is no single statute that explicitly prohibits the augmentation of appropriated funds. The concept can be derived from several separate enactments:36

![]() 31 U.S.C. 3302(b), the miscellaneous receipts statute.

31 U.S.C. 3302(b), the miscellaneous receipts statute.

![]() 31 U.S.C. 1301(a), the purpose law, which restricts the use of appropriated funds to their intended purposes. Early comptroller of the Treasury decisions often used 31 U.S.C. 3302(b) and 1301(a) as a basis of support for prohibiting augmentation.

31 U.S.C. 1301(a), the purpose law, which restricts the use of appropriated funds to their intended purposes. Early comptroller of the Treasury decisions often used 31 U.S.C. 3302(b) and 1301(a) as a basis of support for prohibiting augmentation.

![]() 18 U.S.C. 209, which prohibits the payment of, contribution to, or supplementation of the salary of a government officer or employee as compensation for his or her official duties by any source other than the government of the United States.

18 U.S.C. 209, which prohibits the payment of, contribution to, or supplementation of the salary of a government officer or employee as compensation for his or her official duties by any source other than the government of the United States.

180. How are augmentation and the Antideficiency Act related?

If an agency augments its appropriation without statutory authority, and then obligates those augmented amounts, the agency would exceed its appropriated level. Hence, this action would constitute a violation of the Antideficiency Act.

One common example is the prohibition against transfers between appropriations without specific statutory authority. An unauthorized transfer is an improper augmentation of the receiving appropriation.37 Note that the transfer prohibition and the augmentation rule do not apply to reprogramming actions at the agency allotment level within the same appropriation. In these situations, the total amount available in a given appropriation remains constant. Transfers between appropriations, on the other hand, decrease the size of one appropriation and increase the size of another.

There is a rule that a general appropriation may not be used if a more specific appropriation for an object is available. If a specific appropriation is exhausted, agencies may be tempted to use a more general appropriation to continue operations. However, such a practice violates 31 U.S.C. 1301(a), using a general appropriation for an unauthorized purpose, and also improperly augments the specific appropriation.

Although the augmentation rule is related to the concept of purpose availability, it is most closely related to the availability of an amount of funds because it restricts executive spending to the amounts appropriated by Congress. In this respect, it is a logical and indispensable complement to the Antideficiency Act.38

Miscellaneous Receipts

181. What is the miscellaneous receipts statute?

The miscellaneous receipts statute is found at 31 U.S.C. 3302(b). It was enacted in 1849 and states:

Except as provided in section 3718(b) of this title, an official or agent of the Government receiving money for the Government from any source shall deposit the money in the Treasury as soon as practicable without deduction for any charge or claim.

Penalties for violation are found in 31 U.S.C. 3302(d). They allow for the violator to be removed from office and required to forfeit any money held, including such funds to which the violator might otherwise be entitled.39

182. What does the miscellaneous receipts statute mean in practice?

Any money an agency receives on behalf of the government from a source outside the agency must be deposited in the Treasury. This means that the money must be deposited into the general fund (“miscellaneous receipts”) of the Treasury, not into the agency’s own appropriation. The comptroller of the Treasury explained the distinction between the two in 22 Comp. Dec. 379, 381 (1916):

It [31 USC 3302(b)] could hardly be made more comprehensive as to the moneys that are meant and these moneys are required to be paid “into the Treasury.” This does not mean that the moneys are to be added to a fund that has been appropriated from the Treasury and may be in the Treasury or outside. It seems to me that it can only mean that they shall go into the general fund of the Treasury which is subject to any disposition which Congress might choose to make of it. This has been the holding of the accounting officers for many years. If Congress intended that these moneys should be returned to the appropriation from which a similar amount had once been expended it could have been readily so stated, and it was not.40

183. Once an agency deposits money received into a miscellaneous receipts account, is it then barred from taking the funds back out?

Yes. That is exactly why the miscellaneous receipts statute is so significant in ensuring that the executive branch remains dependent upon the congressional appropriation process. Recall the provision in article I, section 9, clause 7, of the U.S. Constitution: “No money shall be drawn from the Treasury but in consequence of appropriations made by law.” Once money is deposited into a miscellaneous receipts account, it takes an appropriation to get it out.41

184. Am I correct in assuming that depositing a miscellaneous receipt into an agency’s appropriation, rather than depositing it with Treasury, would constitute an augmentation of the appropriation?

Yes. Such an action would constitute an improper augmentation of the appropriation to which the money was deposited.

185. No-year appropriations seem to have much more flexibility than fixed-term appropriations. Does the miscellaneous receipts statute apply to these funds as well?

The statute applies even for no-year appropriations. The no-year status relates to the duration of availability of the funds, not to the amount.42

186. Are there any exceptions to the miscellaneous receipts statute?

Exceptions fall into two broad categories, statutory and nonstatutory.43

![]() An agency may retain money it receives if it has statutory authority to do so. In other words, 31 U.S.C. 3302(b) will not apply if there is specific statutory authority for the agency to retain the funds.

An agency may retain money it receives if it has statutory authority to do so. In other words, 31 U.S.C. 3302(b) will not apply if there is specific statutory authority for the agency to retain the funds.

![]() Receipts that qualify as repayments to an appropriation may be retained to the credit of that appropriation and are not required to be deposited into the general fund of the Treasury. These repayments may be further divided into two general classes, reimbursements and refunds.44

Receipts that qualify as repayments to an appropriation may be retained to the credit of that appropriation and are not required to be deposited into the general fund of the Treasury. These repayments may be further divided into two general classes, reimbursements and refunds.44

– Reimbursements are sums received as a result of commodities sold or services furnished either to the public or to another government account, which are authorized by law to be credited directly to a specific appropriation.

– Refunds are repayments for excess payments and are to be credited to the appropriation or fund accounts from which the excess payments were made. They must be directly related to previously recorded expenditures and are reductions of those expenditures. Refunds to appropriations represent amounts collected from outside sources for payments made in error, overpayments, or adjustments for previous amounts disbursed. Refunds constitute the non-statutory exception to the miscellaneous receipts statute. The rationale for this exception is to enable an appropriation account to be made whole by retaining a refund that was the result of an overpayment. GAO decision B-302366, July 12, 2004, states that crediting a refund to an appropriation “simply restores to the appropriation amounts that should not have been paid from the appropriation.”

187. What are the specific statutory exceptions to the miscellaneous receipts statute?

They are too numerous to list. Title 10 of the United States Code spells out several exceptions for DoD, including proceeds from agricultural and grazing leases, sale or lease of real property, hunting and fishing permits, and recycling programs.

Non-DoD examples include 42 U.S.C. 8287 and 8256, which allow retention of savings from energy savings performance contracts and rebates from utility companies for energy-saving measures.45

A major exception that applies to every federal agency is the Economy Act, 31 U.S.C. 1535 and 1536, which is discussed in more detail later in this chapter. The Economy Act allows agencies to collect reimbursement for work performed on behalf of another agency into their own appropriations. Without the Act, intragovernmental reimbursable work would not be possible; any money collected from a customer would have to be deposited into miscellaneous receipts.

Loss of or Damage to Government Property

188. May an agency retain money it recovers for loss of or damage to government property to pay for replacement or repair?

The general answer is “no,” but there are exceptions. Normally, funds recovered for the loss of or damage to government property must be deposited in the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts. The rationale is that appropriations provide agencies with funding to repair or replace damaged or lost property, regardless of how it was damaged or lost.

There are statutory exceptions to this general rule. For example, 40 U.S.C. 321 provides that GSA may credit recoveries for loss or damage to General Supply Fund property to the General Supply Fund. Likewise, under 16 U.S.C. 579c, the U.S. Forest Service is authorized to retain money received from a settlement for damage to land—for example, pursuant to a timber sale.46

Additionally, a recent GAO decision determined that damages recovered by revolving funds may be retained by the revolving fund and are not subject to the miscellaneous receipts statute. The idea behind this decision is that such loss or damage is a cost of doing business, and recoveries should make the fund whole for the losses incurred. However, any amount recovered that is beyond the cost of actual loss or damage must be deposited with Treasury as a miscellaneous receipt.47

189. May the person who lost or damaged government property simply replace it or have it repaired from his or her own funds?

GAO has consistently allowed this practice as a non-statutory exception, even though it seems as if the agency would be doing something indirectly that it may not do directly, thereby bypassing the statute.

It is permissible for a private party responsible for loss or damage to government property to agree to replace it in kind or have it repaired to the satisfaction of the agency and to make payment directly to the party making the repairs. The agency is not required to transfer an amount equal to the cost of the repair or replacement to miscellaneous receipts. This principle was first recognized in 14 Comp. Dec. 310 (1907), and it has been followed ever since. The exception applies even though the money would have to go to miscellaneous receipts if the responsible party had paid it directly to the government.48

190. Suppose one federal agency damages the property of another federal agency. Must the first agency pay for the damage, and may the agency that owns the property retain such payment?

The general rule under the interdepartmental waiver doctrine is that funds available to the agency that causes the damage may not be used to pay claims for damages by the agency whose property was damaged. This doctrine is based on the concept that agencies’ property is the property not of separate entities but rather of the government as a single entity, and there can be no reimbursement by the government for damages to or loss of its own property. Thus, under this rule, one agency may not make payment to another federal agency for damages it caused.49

However, there is a well-established exception to this rule. In B-302962, June 10, 2005, GAO explained it:

The interdepartmental waiver doctrine does not apply … where an agency has statutory authority to retain income derived from the use or sale of certain property, and the governing legislation shows an intent for the particular program or activity to be self-sustaining. 24 Comp. Gen. 847 (1945). Thus, where an agency operation is financed through reimbursement or a revolving fund, the prohibition does not apply. 65 Comp. Gen. 910 (1986). In such cases, the agency should recover amounts sufficient to cover loss or damage to property financed by the reimbursements or revolving fund, regardless of whether that damage is caused by another federal agency or a private party, and deposit those funds into the revolving fund. The rationale for this exception is that the revolving fund, established to operate like a self-sustaining business, should not bear the cost for “other than objects for which the fund was created.”50

Thus, funds recovered from another federal agency for damage to revolving-fund property may be retained by the revolving fund and are not subject to the miscellaneous receipts statute.

Fees, Fines, and Penalties

191. Federal agencies sometimes collect fees, which are designed to offset the cost of providing a service. An example is fees collected under the Freedom of Information Act. Are such fees credited to agency appropriations or to the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts?

Numerous GAO decisions all boil down to one basic rule: If an agency is to retain the fees collected in its appropriation and use them, the agency must have (1) statutory authority to charge fees for its programs and activities and (2) statutory authority to retain and use the fees collected.51

For example, collection of Freedom of Information Act fees is authorized, but they must be deposited as miscellaneous receipts. The rationale is that the government should be compensated for the significant costs associated with researching and copying documents in response to a FOIA request, but the agency is funded by appropriations to comply with FOIA requirements. Therefore, agencies may collect the fees but not retain them.52

192. How are fines and penalties received by the government handled?

Absent statutory authority to retain them, monies collected as a fine or penalty must be deposited in the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts under 31 U.S.C. 3302(b).53 The rule for fees also applies to fines and penalties. The agency must have the statutory authority to impose and collect a fine or penalty, as well as the statutory authority to retain such fines and penalties. Without both, fines and penalties go to the Treasury.

ECONOMY ACT REIMBURSEMENTS AND REVOLVING FUNDS

193. Does the Economy Act, which authorizes an agency to retain reimbursement for work performed on behalf of another agency, constitute a statutory exception to the miscellaneous receipts statute?

Indeed it does. In fact, were it not for the Economy Act and similar subsequent pieces of specific legislation, the concept of reimbursement within the federal government would not exist.

The Economy Act, 31 U.S.C. 1535 and 1536, authorizes the inter- and intradepartmental furnishing of materials or performance of work or services on a reimbursable basis. This statutory exception to the miscellaneous receipts statute authorizes a performing agency to credit reimbursements to the appropriation or fund charged in executing its performance.54

194. What sort of costs may the performing agency recoup for Economy Act work?

Although the allowable costs are normally agreed to in advance by the performing agency and the ordering agency, certain guidelines should be followed.

Agencies should “get what they pay for, and pay for what they get.” In other words, a reimbursement must be for actual costs incurred. If the performing agency charges more than its actual costs, its appropriation would be augmented. If it charges less than the actual costs, the ordering agency’s appropriation would be augmented. Thus, although there is some flexibility in determining costs, they must be reasonable to avoid an augmentation. Generally speaking, an agency should charge for only the incremental, or out-of-pocket, costs associated with fulfilling the agreement. General and administrative or other fixed costs should not be included.

Also, reimbursement may not be credited to an appropriation against which no charges have been made in executing the order because that would constitute an improper augmentation. An example would be crediting reimbursement for depreciation to an appropriation that did not bear any costs of the transaction. If a specific procurement appropriation had been used to purchase a piece of equipment, it would be improper to credit depreciation of that equipment to an operating appropriation that used the equipment to fill the customer’s order.55

195. May every agency use the Economy Act to get reimbursed for any work it does for another agency?

Although the Economy Act is available to every federal agency as a vehicle to be reimbursed for providing goods or services to another agency, the authority is not unlimited. Agencies may not use the Economy Act to obtain reimbursement for a service that is a normal part of the providing agency’s mission and for which it receives appropriations. For example:

![]() An agency acquiring land may not reimburse the Justice Department for the legal expenses incurred in the acquisition because these are the regular administrative expenses of the Justice Department for which it receives appropriations.

An agency acquiring land may not reimburse the Justice Department for the legal expenses incurred in the acquisition because these are the regular administrative expenses of the Justice Department for which it receives appropriations.

![]() Similarly, agencies may not reimburse the Treasury Department for the administrative expenses incurred in making disbursements on its behalf.

Similarly, agencies may not reimburse the Treasury Department for the administrative expenses incurred in making disbursements on its behalf.

![]() Federal agencies may not reimburse the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for services performed in administering the patent and trademark laws because the patent office is required by law to furnish these services and receives appropriations for them.

Federal agencies may not reimburse the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for services performed in administering the patent and trademark laws because the patent office is required by law to furnish these services and receives appropriations for them.

![]() The Library of Congress may not be reimbursed for recording assignments of copyrights to the United States.

The Library of Congress may not be reimbursed for recording assignments of copyrights to the United States.

![]() The Merit Systems Protection Board may not accept reimbursement from other federal agencies for the travel expenses of hearing officers to hearing sites away from the Board’s regular field offices. The Board receives appropriations for such travel. Further, the inability of the Board’s appropriation to fund such travel, whether due to inadequacy or exhaustion, does not permit another agency to pick up the costs.56

The Merit Systems Protection Board may not accept reimbursement from other federal agencies for the travel expenses of hearing officers to hearing sites away from the Board’s regular field offices. The Board receives appropriations for such travel. Further, the inability of the Board’s appropriation to fund such travel, whether due to inadequacy or exhaustion, does not permit another agency to pick up the costs.56

Economy Act orders tend to be voluntary, rather than mandatory, on the part of the providing agency. If the providing agency is required by law to perform a task and receives appropriations for it, then reimbursement would constitute improper augmentation of the providing agency’s appropriation (as well as a purpose law violation on the part of the buying agency).

196. Are revolving funds exempt from the requirements of the miscellaneous receipts statute?

Revolving funds constitute a statutory exception to the miscellaneous receipts statute. Their receipts are credited directly to the fund and are available, without further appropriation by Congress, for expenditures to carry out the purposes of the fund.57

This does not mean, however, that 31 U.S.C. 3302(b) never applies to revolving funds. The statute that chartered the revolving fund specifies the receipts that may be credited to the fund. Receipts that are not related to the operation of the fund must be deposited in the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts.58 A revolving fund established, for instance, to perform ship overhaul may not hold a bake sale or car wash to augment the fund. Only those receipts that relate to the statutory purpose of the revolving fund may be retained by the fund.

GIFTS AND DONATIONS TO THE GOVERNMENT

197. May the federal government accept gifts from outside sources, or is that an improper augmentation of appropriations?

It has long been recognized that the United States may receive and accept gifts. No particular statutory authority is needed. A Supreme Court ruling stated: “Uninterrupted usage from the foundation of the Government has sanctioned it” (United States v. Burnison, 339 U.S. 87, 90 (1950)). The gifts may be of real or personal property and may be made by living persons or through the wills of deceased persons. Monetary gifts to the United States go to the general fund of the Treasury and present no augmentation problem because there is no appropriation to augment.59

198. May a federal agency also accept gifts?

Although gifts to the United States do not require statutory authority, gifts to an individual federal agency are viewed differently. The rule is that a government agency may not accept for its own use (that is, for retention by the agency or to credit its own appropriation) gifts of money or other property unless it has specific statutory authority to do so.60

Thus, the acceptance of a gift of money or other property by an agency lacking statutory authority to do so is an improper augmentation. If an agency does not have statutory authority to accept donations of money, it must turn the money in to the Treasury as miscellaneous receipts.61

Agencies without gift retention authority must report gifts of property to GSA, and the property will be treated in accordance with GSA regulations. Gifts from foreign governments or entities must also be reported to GSA and treated in accordance with 41 CFR 102.36.420 and part 101–49.62

199. Can agencies that have gift-receiving authority get around the miscellaneous receipts statute by classifying some of their receipts as gifts?

If a receipt does not meet the definition above, calling it a gift doesn’t make it one. For example, in 25 Comp. Gen. 637, GAO held that a fee paid for the privilege of filming a motion picture in a national park is not a gift and must be deposited as miscellaneous receipts.63

200. May a federal employee accept travel-related promotional items?

Until 2001, the answer was “no.” But on December 28, 2001, President Bush signed into law a provision allowing federal employees to retain travel-related promotional items for personal use (5 U.S.C. 5702). The law specifically states that a federal traveler who receives a promotional item (such as frequent flyer miles, upgrades, or access to carrier clubs or facilities) as a result of using travel or transportation services obtained at federal government expense may retain those items for personal use. The item must be obtained under the same terms as those offered to the general public and at no additional cost to the government. The Federal Travel Regulation addresses promotional items in 41 CFR 301-53 (2005).64

Antideficiency ACT VIOLATION PENALTIES

201. What are the potential consequences or penalties if an employee violates the Antideficiency Act?

Violations of the Antideficiency Act are subject to penalties of two types—administrative and criminal. The Antideficiency Act is the only one of the 31 United States Code fiscal statutes to prescribe penalties of both types, which underscores congressional perception of the Act’s importance.65

Sections 1349(a) and 1518 of Title 31 state that an officer or employee who violates 31 U.S.C. 1341(a), 1342, or 1517(a) “shall be subject to appropriate administrative discipline including, when circumstances warrant, suspension from duty without pay or removal from office.” Employees have in fact been suspended, reduced in grade, or removed from government service for violating the Act.

In addition, per 31 U.S.C. 1350, an officer or employee who “knowingly and willfully” violates any of the three provisions cited above “shall be fined not more than $5,000, imprisoned for not more than 2 years, or both.”

202. Could someone actually go to jail for using the wrong “color” of money—that is, for citing the wrong appropriation or overspending an apportionment when there is still money left in the appropriation?

Although the statute allows for criminal penalties, no case has been documented in which anyone has been prosecuted for, much less convicted of, a violation of the Antideficiency Act.

It is unlikely that the criminal penalties will ever be invoked, for two reasons. First, the Justice Department will not normally go after an individual unless he or she has personally benefited from the transaction that gave rise to the violation. Justice normally relies on the agency to take administrative action against the perpetrator. If personal gain was involved, other criminal statutes (theft, fraud, conspiracy) carry far greater penalties than the penalty for violating the Antideficiency Act (a $5,000 fine or two years imprisonment).

For example, the Army augmented its appropriation by more than $1 million in 2001 when it used unauthorized credits to fund various rehabilitation and refurbishment projects using contractor employees. The government official found responsible for the violation was prosecuted for felony theft of government property for submitting or approving more than $33,000 in fraudulent travel reimbursement claims. The official was fired and placed under house arrest for six months.

In an Army Corps of Engineers case, four employees used their government purchase cards to make $186,000 of personal nongovernment purchases—a violation of the Antideficiency Act. Two of the employees were dismissed from federal service. One was sentenced to six months in federal prison, and the other received three years of probation. It is unclear from the report under which law they were prosecuted, but it is unlikely that it was the Antideficiency Act.66

Even if someone were indicted for knowing and willful violation of the Antideficiency Act, it would be difficult to get a conviction. Convincing a jury of 12, most or all of whom have no knowledge of appropriations rules, that using the wrong appropriation or over-obligating an apportionment when the underlying appropriation had additional funds warrants a conviction and jail time would be virtually impossible.

Given that criminal prosecution is a remote possibility, the threat of significant administrative penalties is sufficient to evoke compliance with the law.

203. Can an Antideficiency Act violation be avoided by simply not recording some valid obligations, so that the accounting records don’t show a shortage?

Posting an obligation to the accounting records merely evidences its existence. It does not create the obligation, and its absence in the records does not mean it does not exist. If obligations exceed budgetary authority, a violation has occurred, whether or not the accounting records are accurate.

Another caution here: The knowing or willful failure to record an obligation in order to conceal an Antideficiency Act violation is also a criminal offense!67

204. Are the circumstances surrounding a violation (e.g., good faith, lack of intent, minor nature of the violation, inadequate training) ever relevant in determining whether a violation has occurred and whether it should be reported?

All of those circumstances are irrelevant in determining whether a violation has occurred. Further, violations that occur are to be reported. However, these circumstances are usually relevant when assessing penalties against the violator. Such factors as intent, state of mind, workload, and lack of training or effective supervision may all be considered when the agency imposes its administrative sanctions.68

AGENCY REPORTING PROCEDURES

205. What must an agency do if it has violated the Antideficiency Act?

The first step is to determine whether a violation has actually occurred. In some cases—for example, purchasing a prohibited item for which there is no appropriation available—it is obvious that a violation has occurred. Not every situation is so clear-cut, however. For example, if your accounting records indicate that you over-obligated your apportionment by several thousand dollars during a particular period, the prudent course of action is to review the obligations recorded in the records to ensure they are in fact valid obligations and were actually obligated during the period of apparent shortfall. It is not uncommon for obligations to be posted before they are true obligations, and the level of obligations is often overstated. Refer to 31 U.S.C. 1501 for guidance in determining whether the documentary evidence requirement for obligations has been met.

Agencies often have their own regulations detailing the process to follow when a violation is suspected. This may entail appointing a preliminary investigating official to determine whether a violation has occurred.

206. Assuming the agency has determined that a violation of the Antideficiency Act occurred, what is the next step?

Sections 1351 and 1517(b) of Title 31 require the agency head to “report immediately to the president and Congress all relevant facts and a statement of actions taken.” The reports are to be signed by the agency head, and the report to the President is to be forwarded through the director of OMB. Further, the Consolidated Appropriations Act for 2005 amended the Antideficiency Act to add that the heads of executive branch agencies and the mayor of the District of Columbia must also transmit a copy of each report to the comptroller general on the same date the report is transmitted to the President and Congress.69 GAO then publishes an annual summary of all reports received.

207. Can the person named as the violator ask the comptroller general or the courts for relief from the violation?

Unlike pecuniary liability against an accountable officer, for which there is potential relief available from the comptroller general, the courts have ruled (Thurston v. United States, 696 F. Supp. 680 (D.D.C. 1988)) that there is no private right of action for declaratory, mandatory, or injunctive relief under the Antideficiency Act.70 The violation either happened or it didn’t. If it happened, the facts are reported. No relief is available.

208. What happens if OMB suspects an Antideficiency Act violation?

Whenever OMB determines that a violation of the Antideficiency Act might have occurred, it may request that an investigation or audit be undertaken or conducted by the agency. In such cases, a report describing the results of the investigation or audit will be submitted to OMB through the head of the agency. If the report indicates that no violation of the Antideficiency Act has occurred, the agency head will so inform OMB and forward a copy of the report to OMB. If the report indicates that a violation of the Antideficiency Act has occurred, the agency head will report to the President, Congress, and the Comptroller General as soon as possible.71

209. What happens if GAO reports a violation in one of its audits or reports?

Violations reported by GAO in connection with audits and investigations must be reported to the President, Congress, and the Comptroller General in the same manner as described above. In these cases, the report to the President will indicate whether the agency agrees that a violation has occurred, and if so, it will explain why the violation was not discovered and previously reported by the agency.72

210. What if the agency disagrees with GAO’s finding regarding a violation?

If the agency does not agree that a violation has occurred, the report of violation must still be made to the President, Congress, and the Comptroller General, but it will explain the agency’s position.73

211. What happens if the agency not only disagrees with GAO’s finding but also does not send in a report of violation?

Should an agency fail to make the required report within a reasonable period of time, GAO will advise Congress that the agency violated the Antideficiency Act but has not yet reported the violation. For example, GAO advised Congress that the Department of Energy had violated the Antideficiency Act in fiscal years 2006 and 2007 but had not reported the violations to Congress more than six months after GAO found the violations. Subsequently, two months after GAO notified Congress, the department made the required reports and provided copies to GAO.74

ANALYSIS OF ANTIDEFICIENCY ACT REPORTS75

212. How many violations were reported during the period 2005–2011?

A total of 141 reports were submitted. A few of the reports consolidated multiple dissimilar violations into one report, so there were actually 147 violations reported. Several reports cover multiple violations of a similar nature that occurred in the same time frame or were of a continuous nature. I have counted those reports as containing just one violation per report. For example, the Selective Service System consolidated 14 similar bona fide needs rule violations that occurred within a six-week period into one report. This counts as one violation in the following statistics.

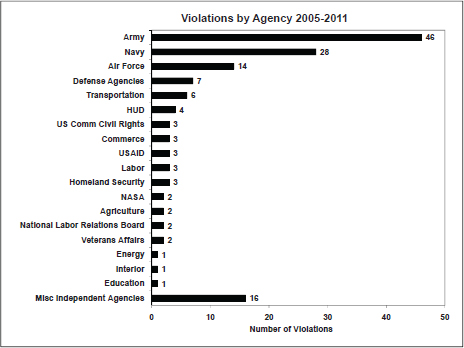

213. Which agency had the most violations during the period 2005–2011?

The number of violations reported by each agency is shown in Figure 4-1. The U.S. Army had by far the most violations, with 46. Collectively, DoD had 95, which represents 65 percent of all violations reported.

214. What was the nature of the violations during the period 2005–2011?

Figure 4-2 shows the types of violations reported.

There were 62 purpose law violations (42 percent of all violations). They are broken down into two categories—using the wrong appropriation for a lawful purpose and using any appropriation for an unlawful purpose (improper purchases). In the former category (38 violations), the wrong appropriation was cited at the time of the transaction, and when a correction to the accounting records was made at a later date, it was found that insufficient funds had been continuously available in the proper appropriation, resulting in an Antideficiency Act violation. There were 24 violations in the improper purchases category. These were purchases made for items for which there was no legally available appropriation. These purpose law violations are automatic violations of the Antideficiency Act.

Figure 4-1: Violations by Agency 2005-2011.

In 33 of the violations, the agency simply over-obligated or over-disbursed its appropriation or apportionment. These violations resulted from myriad circumstances, ranging from financial systems failure to confusion following 9/11 to failure to post obligations in a timely manner.

Another major cause of reported violations involved obligating or expending funds in advance of an appropriation or apportionment. There were 17 such violations. Similar in nature are bona fide needs rule violations, in that they involve obligating current funds for future years’ requirements. Twelve bona fide needs violations occurred.

The three broad categories just mentioned—purpose law violations, exhausting an appropriation or apportionment, and obligating in advance of an appropriation or a bona fide need—accounted for 84 percent of all reported violations.

Figure 4-2: Types of Violations 2005-2011.

215. How were violators during the period 2005–2011 disciplined?

Figure 4-3 shows the types of action the agencies took against the violators. The 147 violation reports identified 300 responsible individuals. The total number of disciplinary actions shown totals 307 because a few individuals were disciplined in more than one way.

In 128 (42 percent) of the cases, no discipline was taken, either because the employee had already left federal service (80 individuals, or 26 percent) or because the agency determined that no discipline was warranted due to the circumstances of the violation (48 cases, or 16 percent).

Oral and written reprimands, counseling, cautions, and admonitions collectively constituted 139 (45 percent) of all disciplinary actions.

Figure 4-3: Discipline Taken By Agency 2005-2011.

Five civilians lost their federal positions, and four military members were removed from their positions.

Fourteen of the reports indicated that discipline was taken, but the nature of that discipline was not reported.

PREVENTING VIOLATIONS OF THE ANTIDEFICIENCY ACT

216. How can I ensure my organization doesn’t incur any Antideficiency Act violations?

While there is no way to be absolutely certain a violation will not occur, there are a number of actions you can take to minimize the likelihood of a violation. Many fall under the umbrella of internal controls. You should have a robust internal control program that complies with the GAO Standards for Internal Control, OMB Circular A-123, and your own agency regulations. Your internal control risk assessments, vulnerability assessments, and annual reviews should include a specific focus on Antideficiency Act compliance.

217. What are some specific actions an agency can take to prevent Antideficiency Act violations?

Good training of funds control personnel is an excellent start. All employees who certify funds availability before obligation (e.g., those who work in your budget office or fiscal control office) should attend an appropriations law class to learn about proper use of federal funds. They should then attend refresher training at least every five years.