CHAPTER 13

The Truth-in-Negotiations Act (Public Law 87-653)

Congress passed the Truth-in-Negotiations Act (TINA) on December 2, 1962, as Public Law 87-653. TINA requires that contractors disclose to the government details about costs they expect to incur during the performance of a contract awarded through negotiated procurement. This disclosure is intended to enable the government to negotiate a price based on a realistic and fully knowledgeable assessment of a contractor’s cost expectations.

The focus of the law is not on the ultimate accuracy of an estimate. If an estimate is “bad” and a contractor benefits with increased profits, this is not a violation of TINA. An “excessive” profit is not evidence of defective pricing, and a contract with a loss (i.e., negative profit) does not mean that defective pricing did not occur. The focus of the law is to require a contractor to disclose (i.e., share with the government) any information that could impact the parties’ agreement on price. Thus, it is vital for a contractor to ensure that relevant data is disclosed before agreement on price.

Violations of TINA are commonly referred to as defective pricing, TINA, PL 87-653, and post-award reviews. The TINA and Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) provisions on defective pricing have been strengthened over the years. Fundamentally, TINA requires contractors to disclose their cost or pricing data and to certify that the data are current, accurate, and complete as of the date of agreement on contract price. To the extent that this certification is not true (i.e., the data were not current, accurate, and complete), the government, under a price reduction clause, is entitled to a lower contract price even on firm-fixed-price contracts subject to TINA.

The objective of TINA is to place government price negotiators on equal footing with contractors by requiring disclosure of cost and pricing data. However, while the contractor is required to disclose data, the contractor is not required to use the disclosed data in developing its price proposal. A contractor may select from available data and exercise judgment in estimating costs and developing a proposed price. However, the nondisclosure of relevant data that were reasonably available, even if the contractor did not consider them in the pricing, is considered defective pricing.1

COVERED CONTRACTS

TINA’s defective pricing provisions apply to the following pricing actions: (1) negotiated prime contracts more than $700,000 in value; (2) prime contract modifications or changes more than $700,000 in value; (3) negotiated subcontracts more than $700,000 in value at any tier, if the prime contractor and each upper-tier subcontractor have been required to furnish cost and pricing data (unless waived); and (4) subcontract modifications or changes over $700,000 at any tier, if the prime contractor and each upper-tier subcontractor have been required to furnish cost and pricing data.

For contract and subcontract modifications or changes more than $700,000 in value, the provisions apply not only to negotiated contracts but also to contracts that were initially the result of sealed-bid procedures. This is necessary, because the government does not have adequate assurance that competitive forces will generate a reasonable price for a contract modification under sealed-bid conditions. When a contractor is undertaking a contract modification, no real competitive forces can be brought to bear, so the government seeks the additional assurance of price reasonableness provided through the disclosure of cost or pricing data.

The $700,000 threshold for contract modifications is determined by adding the upward price adjustments and the downward price adjustments. For example, if a contract modification consists of a downward price adjustment of $400,000 and an upward price adjustment of $400,000, the total modification amounts to $800,000; thus, the modification is subject to the provisions of the act.

Exemption for Adequate Price Competition

A price is based on adequate price competition if: (1) two or more responsible offerors, competing independently, submit priced offers that satisfy the government’s expressed requirement; (2) an award will be made to the offeror whose proposal represents the best value where price is a substantial factor in source selection; and (3) there is no finding that the price of the otherwise successful offeror is unreasonable.

Adequate price competition also exists when there is a reasonable expectation that two or more responsible offerors, competing independently, would submit priced offers in response to the solicitation’s expressed requirement, even though only one offer is received from a responsible offeror. However, in practice some agencies and departments, particularly the Department of Defense, do not readily accept this FAR-based concept. Instead of accepting the concept, an agency or department may require a contracting officer to resolicit to obtain more bidders or to require cost or pricing data from the one bidder.

Consideration must also be given to reflect changes in market conditions, economic conditions, quantities, or terms and conditions under contracts that resulted from adequate price competition. For example, if cost or pricing data were furnished on previous production buys and the contracting officer determines that those data—when combined with updated information—are sufficient, an exception may be granted.

Exemption for Commercial Items

An acquisition for an item that meets the commercial-item definition is exempt from the requirement for cost or pricing data. According to FAR 2.101, commercial item means any item, other than real property, that: (1) is of a type customarily used for nongovernmental purposes; (2) has been sold, leased, or licensed to the general public; or (3) has been offered for sale, lease, or license to the general public. A commercial item is also any item that evolved from and through advances in technology or performance and that is not yet available in the commercial marketplace but will be available in the commercial marketplace in time to satisfy the delivery requirements under a government solicitation. Many government departments and agencies do not look favorably on the classification of items as commercial despite these FAR provisions. The reason for this is that many government reviewers do not consider that anything sold to the government is commercial. Thus, market prices are not acceptable under any condition and the only way to ensure a price is reasonable is to know how much profit the contractor might make.

Waivers

The head of the contracting activity may waive the requirement for submission of cost or pricing data in exceptional cases. This official may consider waiving the requirement if the price can be determined to be fair and reasonable without submission of cost or pricing data.

SPECIAL SUBCONTRACTING CONSIDERATIONS

The government’s right to lower a prime contract price extends to where it had been increased because a subcontractor furnished defective cost or pricing data. The FAR rules governing submission of data require the prime contractor to submit cost or pricing data for subcontracts that are: (1) $12,500,000 or more in value or (2) both more than $700,000 and more than 10 percent of the prime contractor’s proposed price, unless the contracting officer believes such submission is unnecessary.

A contracting officer may request that the contractor or subcontractor submit to the government, or cause submission of, subcontractor cost or pricing data for subcontracts between $100,000 and $700,000 in value that the contracting officer considers necessary.

When a subcontract exceeds the $700,000 threshold, subcontractor cost or pricing data are to be current, accurate, and complete as of the date of price agreement or, if applicable, an earlier date agreed upon by the parties and specified on the contractor’s certificate of current cost or pricing data. The contractor will update the subcontractor’s data appropriately during source selection and negotiations.

The same exemptions that apply to prime contractors also apply to prospective and actual subcontractors. Data are required only from the most likely subcontractor for each component, as long as the prime’s subcontract estimate is based on that subcontractor’s data. These requirements flow down (i.e., are passed on or included in the subcontract provisions) to all tiers; the data of a first-tier prospective subcontractor must include data from the most likely second-tier subcontractors whose proposals are either: (1) over $10 million or (2) over $700,000 and over 10 percent of the first-tier subcontract’s price.

The prime contractor and the upper-tier subcontractors all have a responsibility to review and evaluate the prospective and actual subcontractors’ cost or pricing data that they send to the government as part of the prime contractor’s cost or pricing data submission.

The FAR requires a prime contractor to flow down this standard contract clause in its subcontracts to obtain cost or pricing data from all actual subcontractors before any subcontract expected to exceed $700,000 is awarded and before the pricing of any subcontract modification involving aggregate increases or decreases in costs (plus applicable markup or fee) expected to exceed $700,000, except where an exemption exists. Under the FAR, a prime contractor is responsible for defective data submitted by a subcontractor. To protect itself, a prime contractor may want to include an indemnification clause for defective pricing in its subcontracts. The inclusion of such a clause is a matter of negotiation between a prime contractor and a subcontractor.

What happens when a prime contract is negotiated before the subcontract price is negotiated? Under a flexibly priced prime contract, the government has a continuing and direct financial interest in subcontractor prices that is unaffected by the agreement on the prime contract price. However, when the prime contract is firm-fixed-price, defective data in an actual subcontract submitted and negotiated after the prime contract price has been finalized have no effect on the prime contract price. No audit recommendation for price reduction is appropriate.

A different question arises when subcontracts are awarded before prime contracts. Examples are letter contracts and unpriced change orders. Then, the contract clause requires the subcontractor’s data to be complete, accurate, and current as of the date of the subcontractor’s price agreement rather than the prime’s certification date.

Some agencies will attempt to decrement undefinitized subcontractor prices when negotiating the prime contract price. This decrement is based on previous negotiated reductions in subcontractor prices. In practice, this decrement factor is often not valid because the comparisons of subcontract price versus subcontract proposal often contain changes in the scope of work as well as price reductions. Often the government office doing this analysis excludes any subcontracts where the price increased compared to the proposal. The decrement factor may be based on an assumption that the same reduction can be obtained from all vendors and for all items, but this is a fallacy; a decrement factor should be focused on the item and vendors actually involved in a specific price proposal.

PROVING DEFECTIVE PRICING

The government has the burden of proof to show entitlement to a price cut under the price reduction for defective pricing clause of the contract. Basically, the government must prove five elements:

1. The information provided by the contractor fits the definition of cost or pricing data and it existed before the agreement on price.

2. Current, accurate, and complete data were reasonably available to the contractor before the agreement on price.

3. Current, accurate, and complete data were not submitted to the contracting officer or one of his or her authorized representatives and the government did not have actual knowledge of the data.

4. The government relied on the defective data in its negotiations with the contractor.

5. Defective data caused an increase in the contract price.

Based on FAR Part 15, a contractor cannot depend on these bases for defending an allegation of defective pricing: (1) it was a sole-source supplier, (2) it was in a superior bargaining position, (3) the contracting officer should have known that the data were defective, (4) the agreement was based on total cost and not individual cost elements, or (5) the contractor or subcontractor did not submit a cost and pricing certificate.

Cost or Pricing Data

The government must prove that the alleged defective data submitted are, in fact, “cost or pricing data” before their lack of disclosure can be used to require a price reduction. FAR 2.1 defines cost or pricing data as:

… all facts that, as of the date of price agreement or, if applicable, an earlier date agreed upon between the parties that is as close as practicable to the date of agreement on price, prudent buyers and sellers would reasonably expect to affect price negotiations significantly. Cost or pricing data are data requiring certification in accordance with 15.406-2. Cost or pricing data are factual, not judgmental, and are verifiable. While they do not indicate the accuracy of the prospective contractor’s judgment about estimated future costs or projections, they do include the data forming the basis for that judgment. Cost or pricing data are more than historical accounting data; they are all the facts that can be reasonably expected to contribute to the soundness of estimates of future costs and to the validity of determinations of costs already incurred. They also include such factors as: vendor quotations; nonrecurring costs; information on changes in production methods and in production or purchasing volume; data supporting projections of business prospects and objectives and related operations costs; unit-cost trends such as those associated with labor efficiency; make-or-buy decisions; estimated resources to attain business goals; and information on management decisions that could have a significant bearing on costs.

Although the FAR definition of cost or pricing data relates to factual information rather than to contractor estimates and judgment, factual data are broadly interpreted, and the distinction between facts and judgments may at times be difficult to determine. For example, a contractor’s judgmental analysis involving estimates is factual, and although the government cannot allege defective pricing based on the accuracy of these estimates, it can do so based on the concealment or misrepresentation of judgments.

The definition of cost or pricing data also states that the data must be material enough to affect price negotiations significantly. The question has often been asked: what is significant? Significance is not necessarily based on relative value. The Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals (ASBCA) has ruled2 that approximately $21,000 on a $15 million contract was significant. The ASBCA stated that whether or not the undisclosed data were significant depended on their effect upon the negotiation of a fair price and not upon their percentage dollar effect on the whole contract.

Consider the following example as a more practical illustration of what is and isn’t defective pricing. First, assume that a contractor tells the government that last year’s direct labor rate was $10.00 per hour. This is a fact; if incorrect, this is defective pricing. Second, assume that a contractor tells the government that the estimate for the direct labor rate for next year is $11.00 per hour. This is a judgment; if the eventual rate is $10.80, this is not defective pricing.

Third, assume that the contractor tells the government that the estimated direct labor rate for next year is $11.00 based on last year’s rate of $10.00 and planned escalation of 10 percent. The $10.00 per hour rate is a fact that could be subject to defective pricing. The 10 percent is a judgment; if the eventual escalation is only 5 percent, this is not defective pricing.

Fourth, assume that a contractor tells the government the same statement as in the third scenario but has budgetary data, board of directors minutes, or other documents that indicate that the planned escalation is 5 percent. The 10 percent is judgment; however, if there are additional data that are not disclosed that would have influenced the government’s acceptance of the 10 percent, this is defective pricing.

Fifth, assume the same facts as in the fourth scenario, but the contractor tells the government that the 5 percent is an objective that may not be attained. This disclosure obviates any defective pricing.

Vendor/Subcontractor Quotes

Vendor quotations and subcontractor proposals obtained by prime contractors are specifically included in the FAR’s definition of cost or pricing data. Common questions in this area include: What is the prime contractor’s responsibility to require submittal of, and actually review the adequacy of, cost or pricing data submitted by subcontractors? What if the prime contractor or upper-tier subcontractor did not rely on quotes in pricing its data? Do subcontractor prices settled after the prime has certified its data and negotiated with the government have to be disclosed? Each of these areas is discussed in the following paragraphs.

Subcontractor Data and Prime Contractor’s Responsibilities

Prime contractors are responsible for obtaining and reviewing cost or pricing data from subcontractors. FAR 15.404-3 states that the prime contractor or subcontractor is to: (1) conduct appropriate cost or price analyses to establish the reasonableness of proposed subcontract prices; (2) include the results of these analyses in the price proposal; and (3) when required, submit subcontractor cost or pricing data to the government as part of its own cost or pricing data. Any contractor or subcontractor that is required to submit cost or pricing data must also obtain and analyze cost or pricing data before awarding any subcontract, purchase order, or modification expected to exceed $700,000, unless an exception applies to that action.

Specifically, FAR Part 15 states:

The contractor shall submit, or cause to be submitted by the subcontractor(s), cost or pricing data to the Government for subcontracts that are the lower of either (i) $12,500,000 or more or (ii) both more than the pertinent cost or pricing data threshold and more than 10 percent of the prime contractor’s proposed price, unless the contracting officer believes such submission is unnecessary. The contracting officer may require the contractor or subcontractor to submit to the Government, or cause submission of, subcontractor cost or pricing data below the thresholds covered in (i) and (ii) that the contracting officer considers necessary for adequately pricing the prime contract.

Subcontractor cost or pricing data must be submitted in the format provided in Table 15-2 of 15.408, Instructions for Submitting Cost/Price Proposals When Certified Cost or Pricing Data Are Required, or the alternative format specified in the solicitation. Subcontractor cost or pricing data must be current, accurate, and complete as of the date of price agreement or, if applicable, an earlier date agreed upon by the parties and specified on the contractor’s certificate of current cost or pricing data. The contractor must update the subcontractor’s data, as appropriate, during source selection and negotiations. If there is more than one prospective subcontractor for any given work, the contractor need submit to the government cost or pricing data only for the prospective subcontractor most likely to receive the award.

Depending on the circumstances, the prime contractor and upper-tier subcontractors may conduct these cost or price reviews in a number of ways, ranging from simple desk reviews (particularly in situations involving relatively low dollar value combined with high reliance on the subcontractor’s data) to comprehensive analyses and audits of the subcontractor’s cost or pricing data. For example, the prime contractor or upper-tier subcontractor may have in its files a significant amount of current cost information about the subcontractor that history shows to be highly accurate.

Often, the government’s contracting officer and the prime or upper-tier subcontractor request an assist audit from a government audit agency such as the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA). The contracting officer conducts these reviews if he or she believes that doing so is necessary to ensure reasonableness of the total proposed price. Also, a prime contractor or upper-tier subcontractor may request that an assist audit be conducted, especially if the contractor cannot conduct these reviews or the subcontractor refuses access to its books and records. Procedurally, the request for an assist audit should be made to the requesting contractor’s administrative contracting officer, who will in turn contact the subcontractor’s administrative contracting officer, who will issue the request to the cognizant audit agency.

When it comes to the prime or upper-tier subcontractor’s responsibilities for subcontract cost or pricing data, the question of what types of information must be disclosed to the government often arises. When dealing with identifiable, actual subcontractors (e.g., the price has been negotiated before the prime contractor’s certification with the government), the prime contractor must disclose all cost or pricing data and related results of cost or price analysis to the government and must flow down the subcontract cost or pricing data contract clause. The FAR requires that actual data obtained from prospective subcontractors need not be submitted to the government unless certain dollar and other threshold criteria are met. However, the prime contractor still must disclose to the government the results of subcontract reviews and evaluations as part of its own cost or pricing data submission.

What constitutes results of subcontract reviews? Disclosure is a double-edged sword for contractors. Too much disclosure may be construed as negatively affecting the contractor’s negotiating ability with the government. However, too little disclosure may end in a finding of defective pricing. Generally, a contractor must disclose to the government any factual data that are significant in determining price. This includes the results of fact-findings, audits, and miscellaneous analyses. In ensuring compliance with TINA, however, the government does not require that the contractor use all, or any, of the data in determining its cost or price.

Disclosure to the government of a range of possible subcontract prices or costs by element, based on analysis, is necessary for complying with TINA. The contractor may state, if applicable, that it does not rely on certain areas of that range in developing its price. In this way, some of the prime contractor’s negotiating strategy may be salvaged and compliance maintained; that is, disclosure is accomplished, but judgment is maintained in the estimation process.

A contractor is also responsible for updating the cost or pricing data of its prospective subcontractor. Any subcontractor data that a prime contractor submits to the government must be current, accurate, and complete as of the final price agreement—that is, the date specified on the prime contractor’s certificate of current cost or pricing. Often contractors are misled into believing that on the date of prime contract price agreement the subcontractor data must be updated by the subcontractor. That is not the case—read carefully! The first sentence of this paragraph does not mention timing at all. The second sentence is limited to subcontractor data that a prime contractor submits to the government. A prime contractor is not certifying that as of that date it has the totality of data for the subcontractor.

Contractor Reliance on Quotes

Questions about the need for disclosing data relating to vendor quotes or subcontractor proposals often arise if the prime contractor or upper-tier subcontractor does not rely on the quote or proposal at all in its pricing. In other words: would the data then qualify as cost or pricing data? The safest rule is to make full disclosure and identify the degree of reliance placed on the data. Anything short of this runs the risk of a proposal’s being ruled defective pricing.

Judicial decisions in this area have been somewhat inconsistent, and the resolution of the cases has truly been based on the facts and circumstances of each case. By and large, the facts must be clear enough to show that the data in question were in no way considered by the contractor in developing its price. Furthermore, there should be evidence that the government would not have relied on the data either.

Subcontract Prices Negotiated After Prime’s Price Agreement

TINA requires that all cost or pricing data be current, accurate, and complete as of the “price agreement date” between the prime contractor and the government. As a practical matter, the contract execution date often falls after the price agreement date. The question then arises: Are updated data such as negotiated subcontract prices received after a price agreement date but before a contract execution date to be considered cost or pricing data that should be disclosed? The answer is no. The ASBCA has ruled that the government’s right of recovery to overstatements is limited to “data not current as certified on the contractor’s certificate of current cost or pricing data (that is, effective as of the price agreement date).”3

Notwithstanding the nonapplicability of TINA to data updated after the price agreement date, other problems may come up. For example, if government reviewers determine that a contractor is regularly delaying its finalization of price with subcontractors until after price agreement with the government, they may decide that the contractor’s estimating system is inadequate. This is especially true if the prime contractor consistently negotiates a lower price with the subcontractor than was initially proposed to the government. Trying to resolve this perceived problem, reviewers will often develop a decrement factor to apply to proposed subcontract costs. The decrement factor generally is based on historical trends of average lower negotiated subcontract prices realized by the prime contractor. Often referred to as price-reduction techniques by contractors, the concept of a decrement factor is used by reviewers to question costs in their proposal recommendation to contracting officers.

Nonrecurring Costs

Nonrecurring costs generally involve specific start-up activity and materials that are required on a one-time basis. FAR Part 15 recognizes nonrecurring costs as cost or pricing data needing disclosure to the government. Such costs are often based on engineering estimates. These estimates and related analysis constitute factual data and therefore must be disclosed to the government. Engineering estimates should be well-documented on a rational and overall judgmental basis. In addition, contractors must be careful to identify and disclose any updates to the nonrecurring costs before the price agreement date with the government (e.g., due to changes in scope of work or engineering adjustments to estimating rationale).

Changes in Production Methods or Purchasing Volume

Changes in production methods used or in purchasing volume are factual data that could potentially affect a negotiated price, and the FAR therefore classifies them as cost or pricing data. However, a question arises: When does the change become cost or pricing data and therefore disclosable in forward-pricing proposals? Is it when management makes the decision to change or when the change actually goes into effect? The answer depends largely on the individual facts and circumstances. Generally speaking, whenever management has finalized its decision to initiate a change, that change becomes cost or pricing data as long as the change could reasonably affect price negotiations.

For example, assume that management finalizes a decision to switch its existing manual engineering drawing system over to an automated computer-aided design system. Expected labor productivity improvement is that direct labor will be reduced by 75 percent, but the equipment will not be obtained until approximately one year later. When should this information be disclosed to the government? At a minimum, the contractor would be obliged to disclose its anticipated change on any proposals involving length of performance extending beyond the equipment’s anticipated acquisition date. In addition, the potential productivity improvement factor is a critical factual item that must be disclosed.

Data Supporting Projections

Factual data supporting projections are considered cost or pricing data. Assuming that the data are reasonably available to a contractor and are significant enough to affect price, the data must be disclosed to the government. In reviewing cost rates, government reviewers and contracting officers often want to review the buildup of supporting data. Information such as budgets, accounting records documenting historical material costs, and cost accounting methods used in estimating, accumulating, and recording costs are commonly requested. For forward-pricing rate agreements, the current regulations require that such an agreement be identified each time a new proposal is certified. In addition, the contractor must disclose any change in circumstances or any new data that affect the accuracy of the previously established rate. A contractor’s failure to disclose such changes may constitute defective pricing.

Controversy occasionally arises between the government and contractors in determining the level of detail and type of data that must be disclosed as cost or pricing data supporting projections. For example, government reviewers often want to obtain all budgetary information at all levels within a contractor’s organization, including data referred to as motivational budgets or profit plans. Contractors often take exception to releasing overly detailed information to reviewers on the basis that such data are not necessary for the reviewer’s review of rates.

Unit-Cost Trends

Unit-cost trends are included in the FAR Part 15 definition of cost or pricing data. Common examples of these trends are experienced labor and material costs incurred on previous buys or similar contracts. Such historical data need to be disclosed to the government, notwithstanding actual reliance by the contractor in pricing the proposal.

A contractor need not use a learning curve to prepare an estimate. If a learning curve is used, it should be disclosed. If data for construction of a learning curve are not disclosed, this could be deemed defective pricing. However, a contractor is not obligated to perform a learning curve analysis to avoid defective pricing. Boards of contract appeals decisions stress that TINA requires disclosure of existing data but not the creation of analyses or formats that the government would like to see.

Make-or-Buy Decisions

Make-or-buy decisions qualify as cost or pricing data as they relate to forward pricing on proposals. Such decisions may be made informally or formally, in accordance with the requirements of the FAR. One of the common problems in determining what decisions are cost or pricing data has to do with the contractor’s categorization of the decision as a must make, must buy, or can either make or buy decision. For example, if a contractor proposes that an item is a “must buy” but information reasonably available within the organization suggests that a make is possible, and such data are not disclosed, the contractor could be faced with a ruling of defective pricing.

Management Decisions Affecting Costs

Management decisions affecting costs could qualify as cost or pricing data. Such circumstances can arise in numerous ways. A proposed change in an accounting practice is a common example. Clearly, once management has decided to make the change—for example, alter an allocation method or redefine a cost as direct or indirect—such data must be disclosed to the government. The impact of the change must be reflected in pricing the proposal from the anticipated change date forward.

Reasonably Available Data

The regulations require that data be accurate, complete, and current on the date of agreement on price. The terms accurate and complete are reasonably self-evident. The meaning of current, however, raises questions of lag time in corporate communications and the reasonable availability of certain types of data. The regulations say that the contractor must disclose all significant and relevant data reasonably available at the time of negotiations. Unfortunately, there are no formulaic rules that can be applied to the definition of significant and relevant.

The contractor’s responsibility is not limited by the personal knowledge of its negotiator if the undisclosed facts were known at a reasonably high level in the company. In one Board decision, the fact that neither the contractor’s negotiators nor the person who signed the certificate was aware of an engineering analysis of the subcontractor was not important. The ASBCA determined that the data were reasonably available because some management executives, including negotiators of the subcontract, were aware that the subcontractor’s proposal was excessive. The ASBCA stated:

The appellant is obligated to furnish accurate, complete, and current cost and pricing data to the extent that the data are significant and reasonably available. This obligation cannot be reduced either by the lack of administrative effort to see that all significant data are gathered and furnished the government, or by the subjective lack of knowledge of such data on the part of appellant’s negotiators or the person who signed the certificate.4

A second major lag-time problem concerns updating cost or pricing data at the price agreement date. It is vitally important for a contractor to establish a procedure to update data right up to the point of a negotiated agreement. To ensure that this happens, some contractors have an internal certification process. After agreement on price—but before signing the government’s certificate of current cost or pricing data—a contractor might have key individuals within the estimating system conduct an update analysis, commonly referred to as a data sweep, to certify that all information is current, accurate, and complete. If new data were found, those data would be disclosed to the government. Only then would the certificate be signed.

Given the significance of a defective pricing allegation, the contractor should have an ironclad system of written policies and procedures and associated internal controls so that cost or pricing data can be updated properly. A contractor’s procedure should cover such subjects as changes in make-or-buy decisions, submission of updated forward-pricing rates, changes in escalation factors, updated vendor quotes or purchase orders, anticipated alterations in production methods, and availability of residual materials from previous contracts.

A practical illustration of how to determine the presence of available data is presented in the following situation. A contractor was awarded a contract for fueling hoses. The materials expected to be used were expensive and therefore influential in negotiating the contract price. After the contract was signed, the contractor’s engineers discovered a means to reduce the material content of the hose and increase profits. The key issue in determining whether this is defective pricing is when the company (not the company negotiators) knew that the material could be reduced. If this happened before the date of price agreement, this is defective pricing. If this happened after the date of price agreement, this is not defective pricing.

The FAR formerly required that cost or pricing data be submitted on a Standard Form 1411.5 Although this form is no longer required by the FAR, the same information must still be submitted in accordance with FAR 15.408. During negotiations, the contractor must either (1) submit all documents with a possible bearing on overall costs by physical delivery to the government or (2) specifically identify the documents available to the government even though not physically delivered. The mere availability of these records to the government is not sufficient; specific identification and an indication of availability are required.

Reliance

As a condition of its application, the defective pricing clause requires that the contractor’s submission of defective data caused an overstated price. This requirement depends on proving that in negotiating the contract price, the government relied on the defective data: Had it known the data were defective, the government would have negotiated a lower price. In asserting that the defective data caused a higher contract price, the government need not reconstruct specific amounts attributable to the defective data.

A critical document that may offer valuable information in determining reliance, or the lack thereof, is the price negotiation memorandum (PNM). The PNM, as used by government contracting officers, summarizes the results of negotiations between the government and the contractor. The contracting officer is required to prepare a PNM at the conclusion of each negotiation. The memorandum is then included in the contract file. The FAR requires that the PNM contain these elements:

1. Purpose of the negotiation

2. Description of the acquisition

3. Name, position, and organization of each person representing the contractor and the government in negotiation

4. Current status of the contractor’s purchasing system when material is a significant cost element

5. If certified cost or pricing data were required, the extent to which the contracting officer relied on the cost or pricing data submitted and used them in negotiating the price and recognized as inaccurate, incomplete, or noncurrent any cost or pricing data submitted; the action taken by the contracting officer and the contractor as a result; and the effect of the defective data on the price negotiated

6. If cost or pricing data were not required for price negotiations over $700,000, the exemption or waiver used and the basis for claiming or granting it

7. If certified cost or pricing data were required for price negotiations under $700,000, the rationale for such requirement

8. Summary of the contractor’s proposal, the field-pricing-report recommendations, and the reasons for any substantial variances from them

9. Most significant facts or considerations controlling the establishment of the prenegotiation price objective and the negotiated price, including an explanation of any significant differences between the two positions

10. Basis for determining the profit or fee prenegotiation objective and the profit or fee negotiated.

A contractor should have its negotiators take notes, similar to the Price Negotiation Memorandum (PNM), during negotiations with the government. Negotiation participants should be instructed in the key types of information requiring special attention, such as any updated information disclosed, statements by government negotiators pertaining to reliance or its lack, and disclosed data not relied on by the contractor in cost estimating. As a practical matter, it may be beneficial to consolidate the notes taken by contractor participants into a single document to avoid future confusion; the PNM is a good information source that contractors can use to establish the basis for their compliance with TINA.

Many contracting officers include a statement in each PNM that declares that the government relied on all information provided by the contractor. The intent of this statement is to establish reliance on any data that are subsequently found to be defective. However, a mere statement to this effect may not be sufficient to establish that the government relied on the data. The Boards of Contract Appeals and courts tend to look at the facts; an example of this is the following decision.6

A contractor had proposed a scrap factor based on a previous production model. The contractor disclosed the limited scrap data for the model being priced. However, because the scrap data for the new model were considered limited and not reliable, the contractor elected to price scrap based on the previous production model. The government reviewer would not use the data on the previous model, but instead used the limited data despite the contractor’s objections. Negotiations were held on this basis. Subsequently, defective pricing was found in the scrap data for the previous model, because the data presented to the government was inaccurate. The government demanded a price adjustment, but the ASBCA concluded that the government pricing position did not rely on the defective data.

Price Increase

The government has the burden of proving that the defective data actually increased the contract price and the dollar impact. However, courts and Boards of Contract Appeals decisions have effectively shifted this burden to where there is now a rebuttable presumption that the defective data increased the contract price.7 The principle of natural and probable consequence was apparent when the ASBCA concluded,8 without any specific evidence about the effect of nondisclosure on the negotiated target cost, that it must “adopt the natural and probable consequences of the disclosure as representing its effect.” The ASBCA then computed the price reduction on the basis of the overestimates not disclosed plus related burden and profit.

In the context of defective pricing, setoff means that a contractor’s monetary liability for the defective data that increased the contract price may be decreased or “set off by the amount that other defective data decreased the contract price. The application of setoffs is guided by these parameters:

1. Setoffs apply only within the same pricing action (that is, a contract or its modification) and defects cannot be offset between different pricing actions even on the same contract.

2. Within the same pricing action, setoffs are allowable within the various line items of the cost or pricing data as certified. For example, understated labor can be set off against overstated labor, material, indirect cost, and so on.

3. Setoffs can be applied only against overstated defective data and cannot exceed that overstated amount. A contractor cannot increase the price of the contract through the use of setoffs.

LETTER CONTRACTS

Letter contracts and subcontracts should be avoided by contractors. Under a letter (sub)contract, the contractor proceeds with the work, with price to be negotiated later. Under these conditions, the buyer has a distinct advantage in pricing. First, a letter contract will have a ceiling that, no matter what happens, the price will not exceed. Next, as the price is being negotiated, TINA requires that actual cost data be disclosed for negotiations. If actual costs are less than estimated costs, the buyer can more readily reduce the price during negotiations. (If the actual costs are greater, there is an upside limit for the buyer.) Then, to add insult to the injury already suffered by a contractor, most government profit guidelines reduce the profit level for work already performed on the basis that the risk is now a known, rather than unknown, factor.

How do you avoid letter (sub)contracts? Many sellers do not want to lose a sale and reluctantly agree to a letter (sub)contract. Some sole source contractors refuse on the basis that management does not permit work to be performed without an agreed-to price.

If you must proceed with a letter (sub)contract, try to limit the access to actual cost data. This could be done by having an agreed-to cut-off date for current cost and pricing data of a specific date after signing of the letter (sub)contract (i.e., 90 days after signing). This prevents the most abusive situations where a buyer delays the process until the entire job is complete. Another tactic is to obtain agreement that if price cannot be established within X days, the parties agree to a termination for convenience.

Government rules attempt to prevent these situations, but clever procurement personnel find (create) loopholes. For example, one rule is that a contractor can be paid only up to 75 percent of the contract value if the price is not definitized. An agency might accept a proposal (but does not finalize the price) with a 25 percent profit level (price equals 125 percent of the estimated cost). Thus, the contractor can be paid about 94 percent of the estimated cost (75 percent of 125 percent) before the price must be negotiated. Hardly a deterrent.

PREVENTING DEFECTIVE PRICING

Several actions can help a contractor avoid allegations of defective pricing.

Pre–Price Agreement Cut-Off Dates on Data

A contractor should attempt to negotiate an agreement for a cost or pricing data cut-off date set before the date of price agreement. This earlier date is permitted by law and regulations but is greatly resisted by buyers. This action reduces the risk by limiting the amount of time data must be updated.

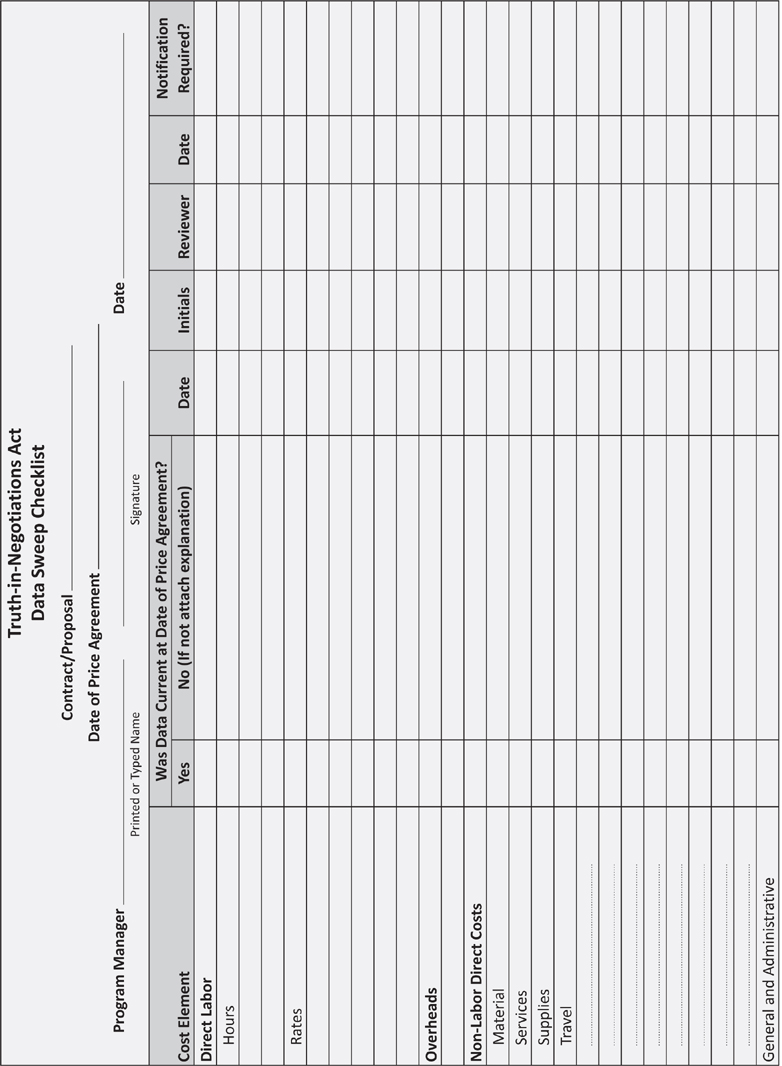

Data Sweeps

The most important action for the contractor is performing a data sweep before signing a certification. After a price agreement, a contractor should not immediate sign the certificate of current cost or pricing data. Instead, it should review its records to ensure that all current data were provided through the negotiation period. If all data were provided, the certificate can be signed; if all data were not provided, the data should be submitted to the buyer with the signed contract, signed certificate, and a cover letter explaining that the data do not significantly impact the price and no further price reductions are being offered. In practice, contractors invariably conclude that the amount is insignificant. If a contractor believes the impact is significant, the contractor should either offer a price reduction or offer to reopen price negotiations.

Illustration 13-1 shows a typical form used to document that a data sweep has been conducted; Illustration 13-2 shows the wording of the certificate of current cost or pricing data.

A contractor might even request departmental or individual sign-offs attesting that a data sweep for the most current data was made. This encourages employees to be diligent in searching for more current data before signing a certificate. This requirement may result in delays in signing contracts, because these employees may prioritize their time toward submitting new proposals rather than verifying that data are current on concluded negotiations.

ILLUSTRATION 13-1: Truth-in-Negotiations Act Data Sweep Checklist

ILLUSTRATION 13-2: Certificate of Current Cost or Pricing Data

Disclaimers

When certain costs or estimating techniques are a known potential risk, a contractor should include uniform protective language in a proposal. Some examples of such routine disclaimers that might be used to help protect the contractor from liability in these areas are:

• Make-or-buy decisions. “We have an ongoing review of make-or-buy decisions. This proposal is based on finalized decisions and does not include the impact of any make-or-buy decisions that are currently under consideration.”

• Location of work. “We have alternative locations for performance of this work. This proposal is based on where we currently believe the work will be performed. At the time of actual contract performance, the location could change due to workload conditions at that time.”

• Residual materials. “We may have residual materials that could be used on this contract. This proposal is based on pricing of new materials only because at this time no residual materials are expected to be used. Any existing residual materials could be used before contract performance, could be deteriorated before contract performance, or could be disposed of surplus materials.”

• Combined quantity buys. “This proposal does not combine quantities of materials from other work in estimating material prices because we do not intend to combine actual purchases. [And, if applicable:] This proposal does not combine quantities of materials within the contract in estimating material prices because we intend to purchase materials in quantities less than the total requirements for this contract.”

• Labor category (time-and-materials contracts only). “We priced direct labor based on our best estimate of the labor category that will be utilized for this work. At the time of actual performance, due to workload conditions, alternative categories may be used.”

• New manufacturing equipment or methods. “We have an ongoing assessment of manufacturing equipment and methods. This proposal is based on finalized decisions and does not include the impact of any new equipment or methods that may currently be under consideration.”

Other Safeguards Against Defective Pricing

The following methods not only protect against allegations of defective pricing but make good business sense.

• Document data submissions. Whenever data are submitted to the government during negotiations, these data submissions should be formally documented.

• Price negotiation memorandum. Contractor participants should maintain good negotiation notes and prepare good price negotiation memoranda. If specific price reductions are made during negotiations, these should be identified in the PNM.

• Consistency. Procedures should exist to ensure consistency in proposals.

• Master list of negotiations. A master list of current negotiations should be maintained so that when accounting changes occur the contractor is aware of what proposal might need updating.

• High-risk areas. A contractor should analyze high-risk areas and address these in the proposal. For example, if residual materials are often an issue, the contractor should state the assumptions and facts related to residual materials.

• Potential and routine issues. Maintain a list of routine issues; a contractor position on these issues should be made known to all contractor negotiators. For example, what is the company practice on uncompensated overtime?

• Record retention. A contractor should retain records based on a consistently applied policy. The appearance of selective retention is not favorable to a contractor if a dispute arises.

• Proposal/contract file. Contract and proposal files should be consistently accumulated and retained.

• Prenegotiation meetings. Contractors should hold prenegotiation meetings to prepare the negotiation team for negotiations.

• Postnegotiation meetings. Postnegotiation meetings should be held to reconcile any conflicting observations by individuals.

Notes

1. For a more comprehensive discussion of the Truth-in-Negotiation Act, see Chapter 9 of Oyer, Darrell. Pricing and Cost Accounting: A Handbook for Government Contractors. 3rd ed. Vienna, VA: Management Concepts Press, 2011.

2. American Bosch Arma Corp., ASBCA No. 10305, 65-2 BCA ¶5280 (1965).

3. Paceco, Inc., ASBCA No. 16548, 73-2 BCA ¶10119.

4. Aerojet-General Corporation, ASBCA No. 12264, 69-1 BCA ¶7664 (1969).

5. FAR Table 15-2 now requests the same information contained in the Standard Form 1411.

6. General Dynamics Corp.. ASBCA No. 32660, 93-1 BCA ¶25378 (1992).

7. Sylvania Elec. Prods, Inc. v United States, 202 Ct. Cl. 16, 479 F.2d 1342 (1972).

8. American Bosch. Arma Corp., ASBCA No. 10305, 65-2 BCA ¶5280 (1965).