CHAPTER 4

Fortifying the Idea Factory

If someone in your company has an idea, do they know what to do with it? And does your organization have a structured process in place, perhaps an idea submission portal on your company’s intranet site? Or do you leave it to chance?

InnovationNetwork, the global consortium of innovation consultants and corporate practitioners, surveyed their 8,000 members on this issue. They assumed that because their members were part of the innovation movement, they would hear of interesting programs. Instead, they received few well-defined responses and candid admissions that “my company’s efforts in this regard are woefully lacking.”

“We had some sort of program to solicit ideas,” said one respondent, “but I’m not sure what became of it.”

Despite the explosion of interest in innovation since that survey was conducted, I’m not so sure that things are much different today in most companies. But things certainly are changing in Vanguard firms. They know that without a system that solicits ideas from everybody and simplifies and streamlines the submission and selection process, there are ideas you will never even hear about.

In this chapter, I’ll show you how to fortify your firm’s idea factory by outlining seven distinct methods of idea management (as this arena of 78innovation is commonly referred to). And then I’ll give you seven suggestions to guide you in designing and implementing a system that is right for your organization.

What is An Idea Factory?

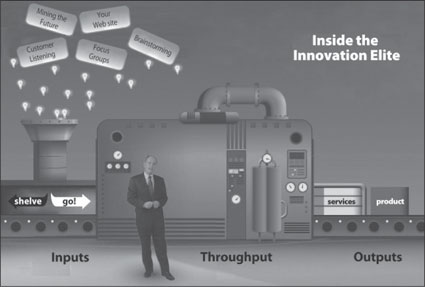

The idea factory metaphor is a way of describing a company’s approach to manufacturing results, whether new products, services, new ways of handling the accounts payable process, whatever. As you can see from the illustration below, every organization has an idea factory that turns inputs into outputs provided there is good throughput. Ideas are the inputs, the raw materials that enter the factory through an intake funnel and, through a process, get developed and transformed into finished goods—new products, new services, business models, and so forth.

If there is poor throughput—in other words poor execution, poor management of ideas—you won’t get output. Perhaps there’s no selection process in place to help you rationally sort the winners from the duds. Perhaps there’s no organized way for ideas to get funding to investigate their potential. Maybe there’s no funding for new ideas period. Without an ongoing, organized system to “process” ideas through the factory, you are at a severe disadvantage. Ideas bottleneck, projects stall, frustration and cynicism take over. Do ideas never get killed in your firm? Without the transparency that an idea management system provides, people with ideas may give up trying before they even begin.

What Vanguard firms are discovering is that with an idea management system in place, concepts move forth like widgets on a production line. Idea systems can help your firm make innovation a disciplined process—part of how you run the business. They can help make the hunt for new possibilities the responsibility of every department and functional area, rather than a select few. Your idea management process can help you gain broader participation from managers and employees.

To fortify your firm’s idea factory, we need to understand and think through and get organized about each phase of the process. We’ll look at how to supercharge the inputs and the number of raw ideas entering your factory in Chapter 6. The next phase is the successful throughput of ideas, which is another way of saying development and execution of ideas. And finally, in the output phase, new ideas come into your production line and get launched into the marketplace.

79

In this scene from the author’s online video “Inside the Innovation Elite,” note how the well-oiled idea factory receives a continuous supply of fresh ideas into the funnel, which then are either shelved or given the green light in the selection process. Once they enter the factory, they follow the development process found in Figure 5, page 145, before finally emerging as outputs. For more information on the video see www.innovationresource.com.

And of course as every innovator knows, the process doesn’t end there. What begins there is actually a whole new phase of marketing and successful commercialization to gain user acceptance. We’ll look at this critical need to build the buy-in for ideas in a later chapter, but let’s look at various models other firms have used. As you read about these models, make notes on the elements you might borrow in designing your own. Let’s begin with a system that is over a hundred years old.

The Idea Management Models

- The Suggestion System Model

- The Continuous Improvement Team Model

- The Open Door Policy Model

- The New Venture Team Model

- The Team Incubator Model

- The Top-Line, All-Enterprise Model

- The Innovation Team Model

Model 1: The Suggestion System

Suggestion programs provide employees an organized system through which to submit ideas and to have those ideas considered by a panel of dispassionate reviewers. The reviewers meet periodically to accept or reject ideas depending on pre-established criteria from management. As an incentive for suggesting solutions, they offer rewards of cash or other tokens. The impetus behind these systems is that rank-and-file workers are often in the best position to see where something could be improved.

Most often, the emphasis is on finding ways to cut costs.

Suggestion programs save companies $2 billion per year, or an average of $6,224 for each implemented suggestion. Popular with manufacturers, employee involvement programs, as they are also called, have been adopted by a wide range of service companies and government agencies as well. In a recent year, contributors received $165 million in cash, according to the Employee Involvement Association in Fairfax, Virginia. While some companies give employees points redeemable for merchandise, the standard award is ten percent of the amount saved during the first year of the idea’s implementation. Some programs pay a nominal fee for successful ideas that have no quantifiable payoff. Managers are usually exempted from the programs, although some firms reward them with bonuses if one of their subordinates turns in a winning recommendation.

American Airlines’ Suggestion Program

Kathryn Kridel, a lead attendant on American Airlines transatlantic flights to and from Europe, noticed that planes were stocked with 200-gram cans of caviar, an ample amount for the full complement of 13 passengers in the first-class cabin. But even when the cabin was almost empty, Kridel and her colleagues still had to open the large cans, which cost the airline $250 each, much of it going to waste. Kridel’s “a-ha”? Require vendors to supply caviar in smaller cans so that when the passenger load was light, less caviar would be wasted.

Kriedel’s idea, which she wrote up and submitted to the company’s suggestion program, was implemented shortly thereafter. It reduced American’s annual caviar consumption by $567,000, and Kridel was awarded a bonus of $50,000. Coworkers jokingly dubbed her the “caviar queen.”

Under American’s program, flight attendants, mechanics, and other 81rank-and-file employees (but not managers) can contribute ideas. Called “IdeAAs,” the program generates 17,000 ideas a year, of which 8,000 are seriously considered, and 25 percent of these are implemented. At the airline’s Dallas headquarters, a department of 47 full-time employees manages the suggestions and makes sure the best ones get implemented. In a recent year, the program saved the airline an estimated $36 million.

Alan Robinson and Sam Stern, in their book, Corporate Creativity: How Innovation and Improvement Actually Happen, examined American Airlines’ program in depth. They found the biggest source of proposals to IdeAAs has always been maintenance employees, and their ideas make up 47 percent of the system’s cost savings. Some mechanics have earned as much as $100,000 for their suggestions.

While interviewing one particularly entrepreneurial duo in American’s program, Robinson and Stern discovered their ingenious method of locating money-saving ideas. One employee who worked in accounting would periodically run a check of maintenance expenditures, scanning for expensive parts that were used in quantity. When he found any that fit the pattern, he would alert his coworker, a lead mechanic for the large jets. This worker would then pull these parts off the aircraft, examine them for patterns of wear or damage, and the two would brainstorm ways to reinforce them to prolong their usefulness. If the mechanic felt American was paying too much for the part, the team would search for less expensive alternatives.

Limitations of the Suggestion Model

Although such cost-cutting zeal is obviously useful to the airline’s bottom line, to these experts, it represents a giant missed opportunity, and points to a glaring limitation of the suggestion model: the potential additional employee creativity American could be tapping but isn’t. “The great number of ideas that people have but don’t pursue—because they don’t think that they will generate cost savings or don’t believe that the cost savings can be measured—are a limitation to all such programs that rely on monetary rewards to encourage cost-saving ideas,” note these researchers. “The more a firm focuses on cost savings, the less likely it is to pursue ideas whose cost savings are not immediately apparent.”

Suggestion programs have been around for over 100 years. They have proved that individual contributors have ideas that can help you cut costs, enhance safety, increase job satisfaction, and raise productivity. Because they 82have been used for so many years by a wide variety of companies, their track record as at least a rudimentary idea management model is proven.

The limitations of this idea management model are low participation rates, requirement of a staff to manage them, and the fact that most are confined to searching for money-saving process ideas. Most of these programs are not designed to stimulate ideas that can grow top-line revenue, such as customer service enhancements, product improvement suggestions, or the realm of strategy innovations discussed in Chapter 1.

Model 2: Continuous Improvement Teams

Similar to suggestion programs, the Continuous Improvement Model primarily focuses on cost savings. But here the scope often encompasses process improvements, product improvements, manufacturing efficiencies, and workplace and quality ideas rather than just cost savings. And unlike suggestion programs that focus on motivating individual contributors to come forward with their ideas, Continuous Improvement Model systems rely on team collaboration. Sometimes called Kaizen Teams, (kaizen is the Japanese word for continuous improvement), they mostly focus on incremental, rather than substantial or breakthrough process on product improvements. Nevertheless, when these seemingly small, continuous tweaks produced by firm’s rank-and-file workers are added up, they can be substantial in their bottom-line impact.

Dana Corporation’s Program

One company that has mastered the Continuous Improvement Model is Toledo, Ohio-based Dana Corporation, one of the world’s largest independent suppliers to vehicle manufacturers and the replacement parts market. The $16 billion company operates 320 facilities in 33 countries and employs more than 82,000 people.

Joseph M. Magliochetti, Dana’s former chairman, is credited with introducing continuous improvement to Dana in the 1980s. Magliochetti was proud of the wide participation of rank-and-file employees. He often shared with visitors how frequent team brainstorming sessions at the plant level generated more than two million ideas per year about how to improve quality, productivity, safety, and efficiency and how the company enjoyed an 80 percent implementation rate of submitted ideas. For example:

83- A Dana worker in the company’s Brazil plant takes continuous improvement so seriously he reported an average of two ideas per day.

- Workers at the Columbia, Missouri, plant came up with ideas that dramatically impacted the assembly process for Isuzu Rodeo rear axles.

- Workers at Dana’s Elizabethtown, Kentucky, frame plant came up with an idea involving a minor process change that allowed the automatic loading of steel sheets into a forming press. This effectively led to the reassignment of six workers and a quicker way of getting the product to the customer.

- A Dana assembly worker hatched the idea to install two bicycle mirrors opposite his work station so he could double-check an assembly without flipping over the 90-pound object, resulting in a 25 percent productivity gain, and a rather pleased employee.

“We believe our people, those doing the job day after day, are the true experts in their area,” Magliochetti once boasted. “It’s our duty to listen carefully, encourage their participation, and garner their support.”

Limitations of the Continuous Improvement Model

Dana’s program is based on the Japanese model, which has been used by Toyota and other manufacturers to create higher quality products while lowering costs. Toyota’s production system, of which the continuous improvement model is the centerpiece, enabled the company to become the world’s largest auto manufacturer. Dana’s embrace of continuous improvement wasn’t enough to counteract disruptive trends in the American automobile industry which was the company’s primary market. In 2006, Dana filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, joining a growing list of suppliers forced to make major restructuring moves because of the slumping U.S. auto industry.

If a company is “meeting its numbers” in the short term, it may be distracted from the critical need to study the big picture trends and undertake strategic changes whose reach is far beyond incremental improvement. If a company is preoccupied with internal efficiency-enhancement and cost-savings ideas, it may be distracted from the external environment. Dana appears to have assumed that incrementalism alone would ensure a bright future, rather than balancing incrementalism with being equally aggressive in going after new markets, diversifying its offerings, developing new 84business models, and inventing superior value-added products as Borg-Warner appears to have done.

To sustain growth, firms need to do more than continually, incrementally improve processes and products. They need idea management systems on an enterprise-wide scale that enable them to capture the passion and creativity in their ranks.

Model 3: The Open Door Policy

The Open Door Model, while widely varying in its practice, is generally one in which the leader, whether division or business unit head, chairman, or CEO, invites contributors to bypass the chain of command and come directly to him or her with any ideas they might have.

The Open Door Model has long being used by leaders who want to communicate the value they place on ideas and to provide a “court of last resort” for frustrated mavericks.

Many of the Innovation Vanguard firms studied for this book use it in conjunction with much more comprehensive idea management processes as yet another way of keeping the firm’s culture open to new ideas. “We have an open-door policy that any employee anywhere can go to any leader in the company that they feel would best address their issue,” says EDS’s Melinda Lockhart. But we’ll see that EDS’s methods are much greater.

Disney’s Gong Show

In his early years as chairman and CEO of Disney, Michael Eisner began hosting idea-pitching Gong Shows, named after a long-since-canceled television program on which amateur contestants would sing, dance, or tell jokes until one of a panel of judges banged on a huge gong, signaling that that person’s time was up. The show’s winning contestant was the one who performed the longest.

Disney’s version of the Open Door Model allowed any employees who thought they had a good idea (and their idea was outside the scope of their day-to-day job) to show up at thrice-yearly Gong Shows and attempt to sell the idea to representatives of top management. These sessions gave Disneyites a structured way to pitch potential breakthrough ideas. Disney lore has it that the idea for the firm’s retail shops (they’ve since been sold) was proposed at a Gong Show by individual contributor Steve Burke.

85

Pros and Cons of the Open Door Model

Open Door is best used in conjunction with other, more comprehensive idea-management programs. Open Door models provide a much-needed safety valve for creative persons with bigger-than-continuous improvement ideas to receive a forum. What is amazing is that this approach, while comparatively rudimentary and primitive compared to other systems companies are designing today, actually works as often as it does.

One type of company culture where Open Door seems to work well is in those where the leader is a maverick. Richard Branson, chairman of London-based Virgin Group, fits this description to a tee. In the past decade alone, Virgin has created nearly 200 new businesses, from entertainment superstores to theater chains, from a low-cost airline to radio stations, and from a passenger train service to a bridal planning chain.

This latter business was proposed to Branson by Ailsa Petchey, a Virgin Atlantic flight attendant. Petchey, soon to wed and strapped for time, decidedly didn’t like how she had been treated in her experience shopping for bridal products and services. She took Branson at his word that his door was always open and presented a whole new business: a one-stop wedding planning shop. Branson liked the idea so much he asked Petchey to become the founder of Virgin Bride, and he provided the seed money.

Model 4: New Venture Teams

The goal of the New Venture Team Model is decidedly not cost-saving ideas, not incremental improvements, and not process innovations. Rather, the goal is more apt to be surfacing (and funding) unconventional product, service, or strategy ideas that have the potential to be breakthroughs.

EDS’s New Venture Team Model

One of the leading practitioners and advancers of this model was Electronic Data Systems of Piano, Texas. EDS embraced new venture teams after cultural assessments indicated a number of deep-seated barriers were dampening new ideas before they ever got to first base. Among these barriers were: no formal recognition within the corporation that “thought leadership” was important; no clear vision or strategy; no investment commitment for new ideas that had no guarantee of payback; no investment governance; no 86channel for good ideas; no ability to go from idea to execution in a seamless systematic manner; an organizational structure that was complex and fragmented; and finally and most damning, no accountability for innovation leadership.

In short, “We rewarded stewardship, not entrepreneurship,” sums up Melinda Lockhart, EDS’s innovation maven. “Our culture was, ‘you take care of your people and you take care of your P&L and you nurture and be kind and we’ll reward and recognize you.’ But if you came up with great ideas, well, there was no compensation for that. In the culture that exists at EDS today, it’s not that we’ve stopped rewarding stewardship. Rather, it’s that these forces coexist and are better balanced.”

The centerpiece of EDS’s idea management system is a program called “Idea2Reality” It operated as an internal market, attracting ideas from employees and funding development of the most promising submissions. Idea2Reality is decidedly not a suggestion program; instead, it seeks growth-producing new products, which EDS terms “service offerings.” In addition, the program welcomes significant process improvements. In designing Idea2Reality, the team sought input from venture capitalists, as well as other companies that had previously introduced this approach to idea management. These organizations had already gained experience in the best ways to attract the attention of a globally dispersed employee base, and in how to select ideas for funding, support “intrapreneurs,” and otherwise manage the process.

To make it easy to submit an idea, EDS employees from Bangkok to Berlin to Piano are encouraged to submit ideas via the company’s intranet. Once an idea is received, a member of the 15-person Idea2Reality support staff then contacts the person to help scope, refine, and further articulate the idea. The Piano-based Idea2Reality staff is really a cross-functional team of business and technology experts dedicated to thinking through the idea and shoring up the business plan for that idea. The team also seeks feedback from appropriate EDS Innovation Fellows who have been awarded this title based on their prior contributions to the company’s top and bottom line.

Next, an executive team reviews the submission and decides whether to award seed funding. This team, which meets twice a month, is chaired by the chief technology officer who is also in charge of innovation corporate-wide. Initial funding can be as little as several thousand dollars. The suggesting employee 87is often invited to further develop the idea at an EDS incubator facility. There the funding goes toward software, market research, airplane tickets for convening focused discussions on the idea, and whatever else is necessary for the idea’s initiator to research the idea during a 30-day period. As with idea incubators that sponsor and assist start-up entrepreneurial firms, the initiator is freed from much of the administrative tasks, which are handled by the Idea2Reality support staff.

At the end of the development phase, the Investment Opportunity Team, a new venture-funding panel composed of key decision makers from EDS’s various business units, reviews ideas that have been submitted. At this juncture, the funding team might decide to reject the idea, award further seed funding, or fully fund the idea for full-scale accelerated development. For “white space” opportunities (those that don’t have an obvious home in a particular strategic business unit), a fourth choice is available. The innovator might be given the green light to seek a joint venture or licensing agreement with an outside firm, or, in rare cases, to establish a new business.

One final design feature of EDS’s approach is how this initiative coexists with the “normal innovation” service offering within each business unit. What Idea2Reality does is to serve as an extracurricular funding vehicle that can develop breakthroughs without the business units having to take a big hit on their P&Ls in order to fund riskier, longer-payoff-type ventures that might occur in the white space between business units.

Limits of the New Venture Model

The New Venture Model of idea management is often what comes out of an ad hoc, “let’s-do-something-in-a-hurry” approach to jump-starting revenue growth, and it can work. But if the new venture team tries to make end-runs around existing business units, or functional fiefdoms (e.g., research and development, marketing, etc.) without first addressing the cultural issues necessary to ensure acceptance of the team’s work, it will almost certainly fail. If a new CEO is appointed who does not support the New Venture Team Model, as was the case at EDS, all is lost, and the new venture team can be disbanded in all of five minutes, since innovative initiative and competence has not been made a part of the larger culture (the “way we do things around here”). Like so many others that have embraced the New Venture Model, EDS achieved initial results. But corporate politics, a change in leadership, and shifting priorities soon obliterated the team.

88Model 5: The Growth Incubator

The Incubator Model of Idea Management first gained prominence during the dot-com era of the late 1990s. When the boom went bust, the Incubator Model seems to have lost favor just as fast. Beyond the hype, the basic idea of incubators is not too different from the “Skunk Works” pioneered by Lockheed Corporation during World War II. Named after the L’il Abner cartoon popular at the time, the independent units were designed to rapidly develop and launch new aircraft by forming small, dedicated teams separate from the bureaucracy.

Xerox’s Blue Sky Incubator

Xerox’s famed Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) is an example of how the incubator model was supposed to help companies develop new ideas. The Palo Alto, California, center, one of seven labs owned by the company, was established with the mandate to do “blue sky” exploration of new technologies, even if they didn’t have an immediate relationship to the company’s current products. During a three-decade period, PARC did just that. Researchers there developed a number of exciting technological advances including the computer mouse, the graphical user interface on which all PCs rely.

But instead of benefiting Xerox, they benefited start-ups such as Apple Computer, Adobe Systems, and 3Com instead. The problem for Xerox was that existing business units in the company never commercialized PARC’s innovations for Xerox. Finally, in a desperate move for survival, Xerox attempted to sell PARC in 2002.

The idea behind PARC and other Skunk Works, is that the separate facility can come up with ideas, but that’s only half the battle. PARC was structured such that developers there, mostly engineers and technical people, were forced to toss their creations over the wall and hope the main organization had the chops to commercialize.

One invention that was the exception was laser imaging, a technology which made it successfully out of PARC labs to become a breakthrough new business for the company. Apparently it succeeded because the person who championed it in the laboratory also championed it in the company. Robert Adams, an engineer with uncommon passion and drive, single-handedly shepherded laser imaging’s development through design, engineering, manufacturing, marketing, and finally, sales.

89Model 6: The Top-Line, All-Enterprise Approach

Tom Terry, a lineman for Verizon Corporation in New York City, spotted a potentially dangerous situation and came up with a special tool to prevent it. Terry’s invention made its way to Verizon’s Champion Program, the company’s well-regarded suggestion system. And in a happy accident of circumstances, the tool eventually became CommGuard, a safety-related product that the company now markets to other telecommunications firms.

As companies challenge their bias that only senior level people can come up with revenue enhancing ideas, they are realizing the untapped potential of individual contributors like Tom Terry. People whose jobs in your company don’t have anything to do with new product or service development often “just happen to think up ideas” in the course of their daily lives. After all, they too are customers in their private lives, and often they use the products and services you produce. Their good ideas aren’t all process improvements, which is the underlying assumption of traditional suggestion systems. What to do with their ideas for new products and services that might just drive growth?

That’s what the Top-Line, All-Enterprise Model of Idea Management is designed to address. Its biggest distinction: this model doesn’t limit the scope of ideas from individual contributors; instead, it invites them, respects them, and gives everyone a place to take their notions, for the good of the firm.

Appleton Paper’s GO Program

Appleton Papers, in Appleton, Wisconsin, the world’s leading producer of carbonless and thermal papers, is one of the first companies to embrace this model of idea management. Their motive in revamping their innovation process? In a word: survival. The problem confronting the company was declining sales of one of its two main products: carbonless papers. Once used in everything from car rental forms to store receipts, you may have noticed how few forms of late you’ve been asked to fill out by hand that used carbonless paper. Appletoh’s other division operates in a growth market, because its thermal paper products are used in everything from bar-coded baggage tags to lottery tickets.

Out of desperation, Appleton created the GO Process, which stands for growth opportunities. “We already had a [suggestion] program for cost-savings ideas,” Dennis Hultgren, Appleton’s senior vice president told me 90during our interview. “With GO, we now regularly solicit ideas from everybody in the company. In one year we’ve gotten over 700 new product ideas from our 2,500 employees. These people are out there, they know our technologies and they are perfectly capable of thinking up new uses [for them]. What we’ve learned is that it’s important to bring everybody in on it. Everybody wants to contribute, but not everyone was being asked.”

Ideas generated by Appleton employees are evaluated by nine cross-functional teams, each led by a senior manager “spoke owner,” who is in charge of championing top prospects to become out-the-door new products. The teams meet several times a month to brainstorm, share insights gleaned from paying investigative visits to other companies, and to keep the momentum going. The nine teams respond to each idea with a “scorecard” that evaluates the idea and gives a detailed explanation of why the product fits or doesn’t fit company objectives and available resources.

Once a month, each team’s report is presented to the firm’s executive committee to determine the status of new product development.

While GO is a new approach, it’s already helping drive growth. A direct result of the GO process includes a new digital paper product that has been released in Germany, and the pipeline is filling with other promising new products as well. “People want to work for a company that is growing and is willing to try new approaches,” Hultgren commented. “This is a whole new way to operate for us.”

Limits of the Top-Line, All-Enterprise Model

The obvious limits of this model are the fact that it is so new and has yet to stand the test of time. It could become a “flavor of the month” approach that a company uses in a slack economy but is abandoned when conditions improve. By suddenly implementing an all-enterprise model without training, the danger is that the program generates a torrent of ideas, but then a bottleneck in sifting, sorting, and reaching consensus about which ones to pursue means that nothing happens.

To make the Top-Line Model pay off, you’ll need to devote attention to developing the entrepreneurial skills of your workforce, and especially your mid-level managers and even front-line supervisors. With even limited instruction in what your senior management is looking for in terms of “growth opportunities” (as Appleton calls them), it may be easier to discover and introduce new products and services and to develop new markets. Additional competence 91will certainly be needed to introduce new products to new markets. Despite these obvious challenges, the All-Enterprise Model has an appeal.

Model 7: Innovation Teams

The gist of this approach is to set up a company-wide network of people with demonstrated skills in innovation and give them very clear marching orders: Go out and find some new ideas that have promise.

Whirlpool’s Innovation Team Approach

Until Whirlpool Corporation adopted this unconventional new method of idea management, growth had come to a standstill, profits were falling, its stock price was at an all-time low, and another cyclical downturn was on the horizon. Management had already tried the usual cost-cutting measures, including the decision to trim ten percent of the company’s 60,000 workers.

Making matters worse, then arch-competitor Maytag had caught Whirlpool Corporation by surprise when it introduced its pricey front-loading Neptune washing machine and watched it win big with customers. Neptune was a wake-up call for the $10 billion firm, and the embarrassment combined with poor performance, was just enough to motivate the company leadership to fundamentally redesign its innovation process, not just come up with a me-too new washer.

The result was Whirlpool Corporation’s Innovation Team. The 75-member group—an international cross-functional collection of volunteers—was charged by senior management with scouring the world for ideas that could generate business growth.

“We had this internal market of people we weren’t tapping into,” explains Nancy Snyder, corporate vice president of strategic competency creation. “We wanted to get rid of the ‘great man’ theory that only one person—the CEO or people close to him—is responsible for innovation.”

The Innovation Team sought ideas from every employee, every region and functional area in the firm. It purposefully didn’t limit the types of ideas it was looking for. Next the team deliberated on what to do with ideas it received, which led to the group’s establishing evaluative criteria. Out of an initial 1,100 ideas gleaned, the Innovation Team identified 80 of the most promising, and out of those, they identified 11 to investigate further, finally winnowing to six to actively pursue.

92One of the six selected was Personal Valet, a new-to-the-world appliance that makes clothes ready to wear by smoothing away wrinkles and cleaning away odors. Another idea was Inspired Chef, which represents a strategy innovation for Whirlpool Corporation’s small appliances division, KitchenAid. Noticing that its many new products needed to be demonstrated to busy households (often time-strapped Baby Boomers), Inspired Chef is designed to do exactly that.

Taking a leaf from Tupperware’s distribution system, the Inspired Chef program contracts with chefs and culinary-school grads to host cooking class dinner parties in customers’ homes. The chef brings all the food and uses KitchenAid’s latest feature-enhanced, goof-proof, cooking appliances, from mixers to juicers, to whip up a meal for the dozen or so invited guests. Most importantly, a catalog full of KitchenAid merchandise is prominently displayed, and the chef takes product orders as well.

A year into implementation, Inspired Chef had a full-time staff of seven people, who coordinated 60 instructors teaching classes in six states. While its top-line revenue potential remains to be proven, the Innovation Team approach gives Whirlpool Corporation a continuous, sustainable vehicle for innovation that invigorates traditional processes.

Designing Your Firm’s Idea Management Process

Having looked at some of the approaches firms use to manage ideas, how might you establish a process that is right for your company? What are the dos and dont’s, and where best to start? Start by considering these issues:

- What do we want our idea management process to do for us?

- How do we expect that this design will enable us to meet those objectives?

- How will our idea management system embed innovation into our company such that it becomes “the way we do things around here”?

Here are ten guidelines to keep in mind as you consider how best to empower the process of idea management in your company:

• Assess how ideas are presently managed.

How satisfied are you that it is the best it can be? How often do employees

93Guideline for Your Own Idea Management System

- Assess how ideas are presently managed.

- The system should solicit ideas from everybody.

- The system must be easy to use.

- The system should have at least one full-time person to administer it.

- The system should give people permission to bypass the chain of command.

- The system should respond promptly to idea contributors.

- The system should have innovation-savvy people in place to review ideas.

- The system should involve the contributor whenever possible.

- The system should give recognition for the very act of contributing, regardless of what happens with the idea.

- The system should integrate different models to fit your firm’s unique culture.

leave to pursue an idea that might have benefited your firm if they’d been able to act on it? What’s working well in the many processes already in place?

• The system should solicit ideas from everybody.

The bottom line is this: If you want people’s ideas, you’ve got to ask for them. And then you have got to have processes in place to handle the ideas you get.

Innovation Vanguard companies realize that good ideas can come from anywhere, at any time. They can come from the sales force and the service technicians who are out talking and interacting with customers every day. They can come from suppliers who may have ideas that could benefit either you or your competitor, whom they also supply. They can come from your receptionist who’s asked questions by callers, and from front-line associates of all stripes. They can come from supervisors, mid-level managers, freelancers, researchers, and even temps (who have a real cross-functional and cross-company view).

They can also come from departing employees who may be disgruntled, and newly arriving employees who bring fresh approaches and insights. They can come from customers and, yes, they even can come from senior managers. Nobody can attach a meter to the basic idea and determine its potential—at least at first.

94

• The system must be easy to use.

For an idea management system to be accepted, ease of use turns out to be a critical success factor. Make your system accessible to people 24/7; when ideas happen, people want to do something with them in a hurry. Their passion is at its peak. Don’t make them wait until Monday. Capture them now.

• The system should have at least one full-time person to administer it.

An idea system only works if there is a reason for people to record the ideas in an effective way. If it is an additional responsibility for someone with a full-time job already, it will always be a secondary priority and won’t get done properly. Result: good ideas will be lost, and people won’t continue to use it.

• The system should give people permission to bypass the chain of command.

Your system should provide an alternative way for ideas to receive a hearing. Permission to bypass the normal chain of command is necessary because a particular employee’s “boss” may not see the efficacy of an idea or may not wish that employee to pursue it for fear of “losing” that employee. The manager may stifle an idea that the employee feels strongly about. Unless this safety valve is an accepted part of the system, employees will tend to pursue only those ideas they know will please their immediate managers. A perfect time to publicize this “rule” is when you are implementing your new idea management approach; that way, nobody takes it personally, yet everyone is put on notice that they are no longer the final say when an employee has an idea.

• The system should respond promptly to idea contributors.

The biggest cause of failure to any system is that it takes too long to get back to people. One system we learned about promises that if an idea hasn’t been acknowledged in 20 business days, it automatically goes to the president’s desk. A rapid response that says “thanks for the idea, here’s what you can expect to happen,” provides much needed feedback and encouragement.

• The system should have innovation-savvy people in place to review ideas.

The committee or team that reviews the ideas must understand that most new ideas seem like duds at first. If looked at through traditional ROI95 measures, few make sense. The most common mistake is to assess new ideas that need significant funding through the conventional metrics of financial projections and planning. If the idea is a potential breakthrough, it creates the future, rather than just extrapolates a future that is like the present.

If the idea is truly original, it solves a problem the customer may not even be aware of having or consider being a problem. The idea will create a new market, as we’ll see later in this book. That’s why you have to carefully select the people who will sit in judgment of ideas. They must have a feel for the future and be broad-based and diverse in experience. They must have experience in championing ideas, must be able to be imaginative, to boldly challenge industry assumptions and holy grails. They must themselves be able to imagine not just new products, but new markets as well. Choose carefully!

• The system should involve the contributor whenever possible.

It is critical how this team responds to ideas it can’t use right now. You’ll need to teach your people how to give and receive feedback on their ideas. If we reject some ideas out of hand without providing an adequate justification, we lose the goodwill and creativity of individuals.

If ideas are rejected in such a way that employees lose face, you lose not only them, but all the people around them.

If ideas are converted into reality without the idea-spawner being rewarded, this is apt to stifle future ideas. Supervisors need to be able to recognize good ideas when they see them and to access them when needed.

• The system should give recognition for the very act of contributing, regardless of what happens with the idea.

This recognition can range from a simple verbal thank-you or personalized email to naming people at staff or company meetings to plaques or certificates. Acknowledgement will increase the ideation rate.

• The system should integrate different models to fit your firm’s unique culture.

Finally, in designing your idea management system, you’ll want to borrow from the best, but invent your own. None of these models is perfect by any means, and the more you examine them, the more you’ll see how much they overlap. None is complete in itself, and they can be “mixed and matched” to produce a stronger overall approach.

96Most important, none of the systems we’ve looked at is “plug and play,” ready for implementation in another company. Benchmarking for the purpose of importing another company’s system into your own will not work. You and your colleagues will do well to develop your own. By addressing these, you’ll achieve an idea management process that will drive growth for years to come. And what’s more, you’ll be ready to actively search for opportunities, which is the subject of the next chapter.