Corporate Policies and Trust

Trust is a central theme in many aspects of security and must be foremost in your mind when discussing security policies. In a perfect world, there would be no issues with trust; you would trust everyone, and they would always do the right thing. Unfortunately, that is not realistic, nor does it take into account other factors, such as bugs in network resources. Again, trusting the resources on your network would be great, but remember that buggy hardware and software is commonplace in networking.

A security policy can be written with the belief that no one in an organization is to be trusted; however, that would not likely work. It is a well-known fact that users circumvent policies that are too restrictive. For example, in my organization we run an R&D lab, and the overarching posture is one of restriction and lockdown. It just so happens that the individuals doing our R&D are Ph.D.s and big types who continually circumvent the policy so that they can do things such as testing and downloading of the latest and greatest and coolest “gadgets.” It is frustrating from an information assurance (IA) position and from the position of having to enforce and reiterate to these developers why they cannot do what they want. There needs to be a balance between trust and securing the network. This balance is different for each organization, but the need for security does not change. To begin this journey into trust and balance and defining what is acceptable from a risk perspective, let us first look at the importance of having policies that reflect current threats. That is, make your security policy pertinent and continually update it. The second aspect you need to look at is the importance of user awareness and education.

Relevant Policies

Many times I have sat down in a new organization and asked the “CXO” in charge (that is, COO, CFO, CEO) to review his/her current security and IT policy letters, and the answer is, nine times out of ten, “...we haven’t reviewed it since we wrote it X years ago or we are working on that—it’s in flux....” Not having a current policy set is unacceptable and opens your corporation to significant risk from a business and technical perspective. If you are reading this and do not know what the date of your last policy is, make a note to yourself to check it in the morning. With the number of new standards coming out, the threat of new network incursion, and the potential threat of lawsuits, you cannot afford to let this be a nonissue. If worse comes to worst and you need to be held accountable, like the TJX corporation you just read about, and you don’t have a current enforced policy, you will find yourself on the losing end of the lawsuit.

Notice I say enforced. If you have a policy and do not enforce the application of the policy, the policy does you no good. It is but clanging brass and cymbals. The first part of enforcing a policy is end-user education.

User Awareness Education

Congratulations! You and your IT staff have spent hours cooped up in a hot conference room, wading through hours of arguments, jockeying for position, and fighting for industry best practices to meet in the middle...you have achieved balance, the zen of IT security policy, your opus! You and your team pat each other on the back, wrap it up neatly in a three-ring binder, and hand it off to the boss; and there it sits, flaccid and dormant, doing nothing more than gathering dust on a shelf. You need to implement the policy, and you begin by having training. You must educate your end users about proper security awareness. If you use a PKI smartcard for logging in to the organization’s computer systems and you are implementing a policy in which the users are required to remove the card from their keyboards when they leave their office/cube, you need to tell them; otherwise, they won’t know, and how are you to enforce the policy if something happens?

Part of your security policy should reflect training; if it doesn’t, look at your IT security policy again. Make yearly refresher training compulsory, and follow up the yearly training with a publication. The time and overhead that you spend tending to this detail will be offset by the confidence that your personnel, IP, and networks are protected. Find creative ways to get the word out. A few good examples are a security awareness day, voice messages, video messages, and succinct email campaigns and posters.

And lest I forget, being a victim of this oversight myself...your IT staff needs training, too. Don’t expect to implement an IT security policy, expect your employees to adhere to it, and expect your IT staff to know and understand what the latest threats and newest designs for protection are. They will not. The industry and threats evolve too rapidly. Too many times the staff implementing the policy cannot enforce it, but not due to apathy. No! This inability is due to ignorance. Don’t expect your staff to accurately implement your security requirements if they do not understand them.

Coming to a Balance

When considering the level of trust to write into a security policy, consider the following items and keep them in mind as your policy is being developed:

• Determine who receives access to each area of your network based on their roles by using role-based access control (RBAC).

• Determine what they can access and how (RBAC).

• Balance trust between people and resources (segregation of duties).

• Allow access based on the level of trust for users and resources (RBAC).

• Use resources to ensure that trust is not violated and the risk is managed and measured.

• Define the appropriate uses of your network and its resources (Network Admission Control [NAC] or Group Policy Object [GPO]).

You need to consider many other things beyond this short list, including your company’s politics and users’ reactions. A security policy cannot account for every consideration, but you need to understand the reactions that a security policy brings out in people—your team needs to be business enablement focused, and there will be compromises for both of your teams along this long road and partnership.

Corporate Policies

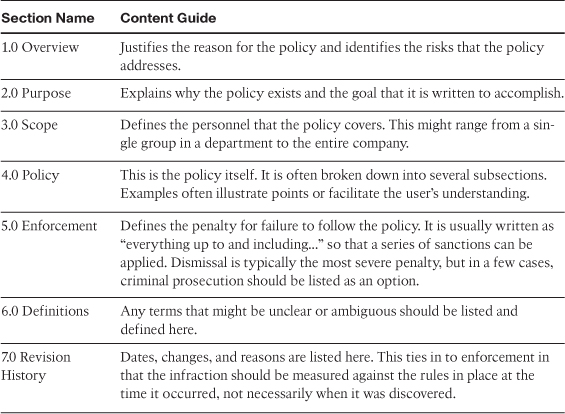

According to the SANS Security Policy Project, security policies should emphasize what is allowed, not what is prohibited; where appropriate, supply examples of permitted and prohibited behavior. This way, there is no doubt—if not specifically permitted by the security policy, the behavior in question is prohibited. The security policy should also describe the ways to achieve its goals. Table 2-2 lists the security policy sections and describes their content.

Table 2-2 Generic Description of a Security Policy’s Contents

Your security policy defines the resources or assets that your organization needs to protect and the measures you must take to protect them. In other words, it is, collectively, the codification of the decisions that went into your security stance. Policies must be published and distributed to all employees, owners, and other users of your systems. Management should ensure and champion by support that everyone reads, understands, and acknowledges their role in following them and in the penalties that violations can bring.

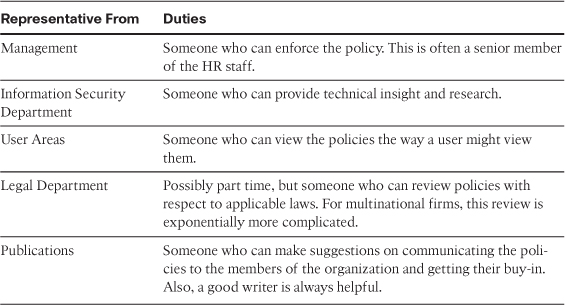

As stated previously, you can trust everyone or trust no one; neither option works effectively when trying to balance productivity and security. Users all have differing views as to a network’s security needs, and they all have a certain level of inherent fear. Users fear that their jobs might be more difficult as a result of security or that they might be punished if they make a mistake or forget to do something. Ultimately, people at any level do not like to feel restricted when they are trying to work. These kinds of attitudes are normal, emotional reactions, so they must be understood and appropriately managed for the security policy to provide balanced protection for your company. Building involvement, or “buy-in,” in security policy development by including representatives from the areas listed in Table 2-3 is highly recommended.

Table 2-3 Members of the Policy Review Team, Council, or Board (Partially from the SANS Security Policy Project)

You can avoid the personal minefield if you ask the involved groups for their input as part of the policy development process. This enables you to do a little social engineering for the good folks by allowing these groups to participate in the process; they will more readily accept increased security restrictions in this case.

The following section reviews some actual security policies that we’ve used in the past and helps define how we write a security policy.