Chapter 5

Assembling the Team

Teamwork Basics

With the paperwork in order, the job budgeted and scheduled, and the creative brief in place, it’s time to design. The question is, if it hasn’t already been answered in the planning process, who exactly will be working on this project? Sometimes, this question is moot: For a solo designer or a small firm, the choices are limited. However, larger design firms may have multiple teams who can collaborate and who possess complementary skills—such as writers, web programmers, and photographers—to fulfill a project’s requirements. It’s a good way to boost expertise, but it also opens the door to complications, from financial to temperamental, which may need to be addressed. These are not insurmountable problems; they’re just more details to be managed properly.

All design teams, large or small, require these things for optimum performance:

▸ Clear goals and objectives

▸ Unambiguous scope of work

▸ Well-defined expectations

▸ Delineated roles and responsibilities

▸ Relevant information and background for the project

▸ Sufficient time in which to work

▸ Appropriate technological tools

▸ Effective collaboration

▸ Ongoing communication

▸ Meaningful recognition and reward system

▸ Oversight and management support

▸ Consistent processes, from creative to communication

▸ Agreed-upon chain of command and functional authority

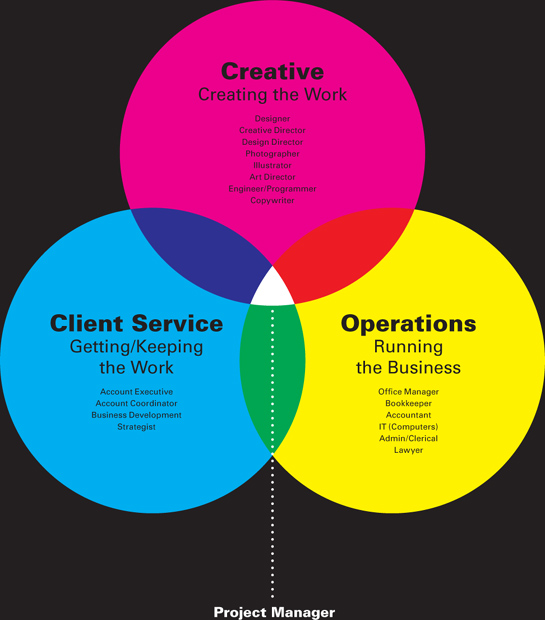

Team Composition

Typically, a project has a core design team consisting of a creative-focused and a client-focused professional. In many instances, more designers are added—some to take a hands-on creative role and some to provide more of a production or finishing capability. In addition, team members with a particular skill set may be added—for example, an illustrator or a print production manager. When a design firm gets larger, not only does the team expand, but there is also the option of adding administrative management personnel to help run the firm. They work to directly support creative and client service because they provide financial and administrative duties that make projects and the firm run better and more smoothly.

For any design team to work well together, each person needs to recognize that his or her performance affects the entire group in its ability to solve problems, develop creative, and satisfy the client. The more they understand what their contribution is to the project, the more attainable great results can be. When things are fuzzy and undefined, it’s easy to believe it’s someone else’s responsibility to handle a certain task. Poor team performance often is the result of poor communication and an ineffective collaborative environment.

The Creative Mix

Selecting the right creative people for a team can be challenging. Just because someone has relevant experience and a great portfolio doesn’t ensure a wonderful fit. There are a variety of subjective factors to consider when choosing creative talent:

• Chemistry: Do you like this person?

• Style: Does this person fit in with the group?

• Attitude: Is the person positive or negative, cynical or enthusiastic?

• Design sensibility: Is it the same or different from ours?

• Professionalism: Is the person as buttoned up (or as loose) as the rest of the crew?

• Sense of humor: Does the person have one? (A little humor goes a long way in a stressful situation.)

• Temperament: Is it even-keeled? Will we have harmony with this person?

• Speed: Is the person used to a fast-paced or a slower environment? What’s the person’s approach?

Team Work Flow

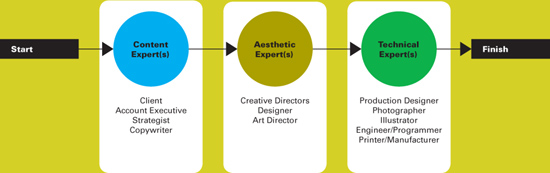

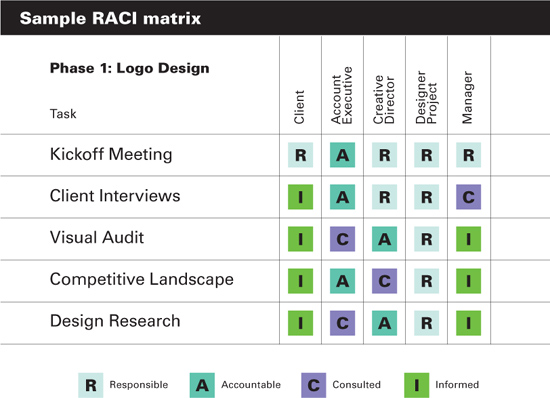

Besides these personality-related factors, design teams need the right mix of skills and abilities. Design projects move from big-picture concepting to the highly detailed finished piece. This is achieved through a kind of “relay race,” handing the project from content experts to aesthetic experts to technical experts, as the job moves from kickoff to completion (see chart below). Often, the only person constantly participating in the project is the project manager, who is involved in monitoring every aspect.

Every design team needs to be aware of and constantly be working to improve their teamwork, some aspects of which include

• Reliability

• Cooperation

• Knowledge sharing

Teams have obligations to each other and to the project they are working on. Project managers should bridge gaps and facilitate communication and work flow among team members. Project managers are the conduit that helps ease the difficulties of disparate personalities, expertise, and working styles.

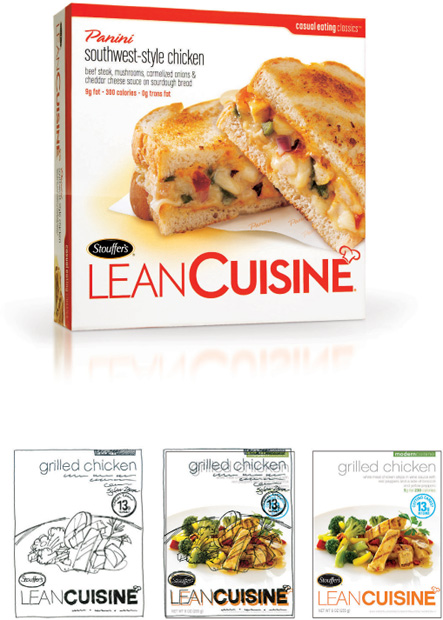

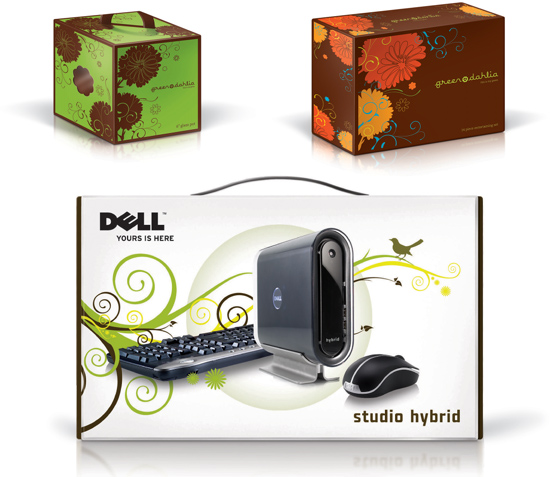

Dunkin’ Donuts is an international coffee and baked goods retailer that was founded in 1948 in Quincy, Massachusetts. It serves about 2.7 million customers per day at approximately 8,800 stores in thirty-one countries, including approximately 6,400 Dunkin’ Donuts locations throughout the United States. Dunkin’ Donuts is well known for its advertising, especially in its home region. Wallace Church worked with the brand to create special winter holiday promotional packaging.

Wallace Church used the well-established brand language and visual iconography to create the special winter holiday packaging. Donut boxes and coffee cups—the primary way customers experience the brand—were designed with bright circular graphics following Dunkin’ Donuts’ identity system.

“When in doubt: ‘Think big, go small. Be smart, be simple.’”

—Rob Wallace, managing partner and strategic director, Wallace Church

Six Characteristics of Successful Design Teams

Virtual Teamwork

Not all design teams comprise members of the same firm collocated in the same office. Lots of design teams consist of people across several geographic locations, time zones, and even companies. Technology makes it possible to bring together interesting combinations of talented people. It’s an exciting possibility, but like every other aspect of the design process, virtual teams require management.

In some ways, managing a virtual team is like managing people face to face, but a few things must be adjusted to make it work smoothly:

• Launching a project with a face-to-face meeting, if possible, is great for setting the proper tone and helping to facilitate a sense of personal connection among team members.

• Written forms of communication, such as email, can easily be shared and subsequently referred to later if necessary.

• Use of technology, especially web-based project management software, is a given.

• Being able to create virtual “war rooms” (i.e., collections of discovery materials held in one location) where people can review visual material and documents is essential.

• At some point, real-time viewing and discussion of work in progress must be facilitated.

• Some activities, such as brainstorming, may be better accomplished with shared physical proximity. Distance may slow certain processes, if not completely impede them.

• Camaraderie in design must be facilitated. Many elusive creative moments come from being in proximity to other creative people. Alternative scenarios need to be provided for this type of interaction to occur in some way.

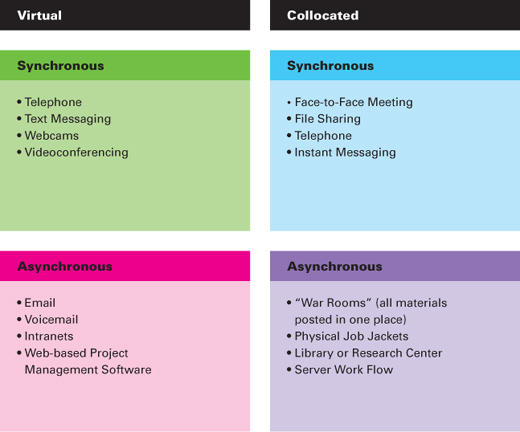

Technology Tools for Teamwork

Synchronous means working at the same time, while asynchronous means working at different times. Virtual teams are dispersed, while collocated teams are together in one place. This chart offers some ideas for tools that can help facilitate teams, no matter what their configuration.

• Verification of information must be pursued. Not everyone understands text-based messages. Voice inflection, as well as nonverbal communication, can often change the meaning of words. Managers need to make sure the team gets the right message.

• Teams that represent a variety of cultures—based on everything from ethnicity to geography to expertise in allied but different industries—can present a challenge, especially when none of their work time is face to face. Barriers come down when people can interact personally.

• Shared processes and agreed-upon work methods will bond the group. Having a team code of conduct will diminish misunderstandings and make the team more cohesive.

An asynchronous environment, in which team members and the client are not viewing and discussing the work simultaneously, can lead to lots of misunderstandings. Managing reactions and feedback becomes challenging in that context. Certain meetings, review sessions, and conferences should occur with all team members logging in or calling simultaneously. This is particularly important for initial creative concept presentations. Having the design team and the client participate directly with each other will allow real-time discussion, timely input, and group resolutions.

Useful Questions for Screening Creatives

Whether you are hiring a staff designer or selecting a temporary collaborator for a project, you need to interview this person. Many design firms make hiring decisions based solely on portfolios. A lot of relevant information is contained in a portfolio: Style sensibility, attention to detail, quality, and experience are all obvious. But what else can you uncover about the person behind the work that would help you make an informed choice? Here are some openended questions to ask:

▸ What was your last project? What did you learn from it? What did you like and dislike about it?

▸ Describe your work process on a typical project. How do you approach design?

▸ Which pieces in your portfolio are you most proud of? Why?

▸ What kinds of clients do you prefer to work with? Why?

▸ Which clients in your portfolio were like this? Which ones were not?

▸ What kind of creative direction did you have on this particular project? How do you like to be supervised? What make a good boss?

▸ What are your professional goals? Where do you see yourself in five years? What do you think are your strong and weak points? What are your plans to improve your deficiencies and enhance your strengths?

▸ What organizations or activities do you pursue that enrich you as a designer? What professional societies are you a member of and how have they helped your career?

Remember that these questions are meant to aid in discussions that reveal more about the person you are interviewing. However, it is against the law in many countries to discriminate on the basis of gender, age, ethnicity, region, sexual orientation, skin color, or national origin, so steer clear of any conversations that touch on those topics.