Chapter 2

Project Setup

Getting Design Off to a Good Start

All design engagements generally follow this encapsulation of the designer’s work flow:

▸ Listen to a problem.

▸ Think about it.

▸ Form ideas.

▸ Sketch some design solutions.

▸ Present/sell the design.

▸ Get it approved.

▸ Make finished artwork.

▸ Possibly hand it off to others to produce.

▸ Deliver it.

▸ Bill it.

Although their projects may vary in complexity and duration, designers perform these activities over and over throughout their careers.

Organizing and Persuading

Effective use of organization and persuasion skills determines whether a design project succeeds or fails. In design and project management, to organize means to create a workable structure and prepare for the design team’s activities. It means taking responsibility for the orderly progression of the work required.

In project management, persuasion concerns the designer’s ability to cause someone—whether it is the client or members of the design team—to do something required during the project. Setting the stage for empowerment and having the stakeholders in a design project agree upfront to be managed is critical. In this way, persuasion begins the moment the designer takes on a project.

Basic and Broad Strokes First

Laying a good foundation is an important first step for any design project, large or small. Start by answering these simple questions that lead to forming a creative brief:

• Who is the client? What is their problem/need?

• What are we doing for them? What is our known list of deliverables?

• When is it due? What are the project milestone dates?

• Who do we want to work with on this job (internal /external team members)?

• What is our budget? How will we allocate it?

The importance of obtaining this information and summarizing it in a creative brief cannot be stressed enough. You should write a creative brief at the beginning of each project. The creative brief allows design concept work to be initiated, and continues to guide project management during design implementation.

Contracts Assist Project Management

The creative brief is just one of the tools that guides designers in their work. Another vital document is the contractual agreement between the designer and the client. This agreement—sometimes called a proposal, estimate, or deal memo—is a formal contract for design services to be rendered to a client for a set fee.

Never Practice Design without a Contract

No designer should begin work on a project without a legally binding agreement. Why? Because it is one of the most important tools for

• Establishing the professional nature of the design engagement

• Defining the work to be done, including the number of revisions

• Outlining the process by which the work will be accomplished

• Formalizing the working relationship between the designer and client

• Building trust and, ultimately, acceptance of the designer’s work

• Acting as a powerful communication vehicle for both designer and client to visualize how work will progress

• Ensuring that the designer is not taken advantage of and the client gets what they expect

• Providing a substantiating document that will stand up in court or in legal arbitration if the designer–client relationship turns bad

Although a well-written and signed designer–client agreement can stand up in a court of law, nine times out of ten, the most important role of the designer–client agreement is as a communication tool. It is a means for the designer and the client to discuss and define the scope of work the designer will provide, and the compensation the designer will receive, for a project they are about to work on together. Once agreed to, it becomes an excellent reference point to guide all design work and project management thereof.

Designer–Client Agreements

Understanding that there are both perils and advantages in describing the SOW on a design project before a designer truly understands what needs to be done, what, then, is the best approach? Covering a few basic details will suffice.

Include the following when scoping:

• A brief summary of the project’s goals and objectives.

• A list of the component deliverables—for example, an identity package comprising a logo, tagline, and basic business papers, including letterhead, envelope, and business card.

• In some cases, a simple definition of the component deliverables’ structure or size—for example, the number of pages in a brochure or on a website. Often, until the design concept is developed, the precise structure is unknown.

• Delivery media. For example, is it an online project? Will the designer post it or simply provide files? For a print project, will the designer buy printing or hand off artwork to the supplier?

• Glaringly obvious services that are not included in the agreement. If such things as photography, copywriting, or manufacturing are relevant to the project, they should be included. These and other expense items might be purchased by the client, or perhaps the designer will estimate them later once the design concept is approved. Whatever the circumstance, make it clear.

Tools for Organizing Design

Along with the basic structural blueprints—the creative brief, designer–client agreement, SOW, and process outline—designers can also employ some specific tools to help them organize project work flow. The main objective here is to provide constant communication and oversight of the project. Everyone involved in the design—both the designer’s team and the client’s—needs to have the project’s scope, vision, and goals at hand.

Typically, there are hundreds of details to consider, respond to, incorporate, and handle. Each team member tends to focus only on his or her own piece of the project, so someone has to keep the overall picture in mind. This is the role of the project manager.

Because design firms are often small businesses, it is common to have only one project manager who is responsible for all projects. Therefore, it is not unusual to have a design manager who is sweating the details of specific projects as well as monitoring the firm’s overall work flow. Details on top of details present themselves and must be considered and prioritized in a kind of constant triage.

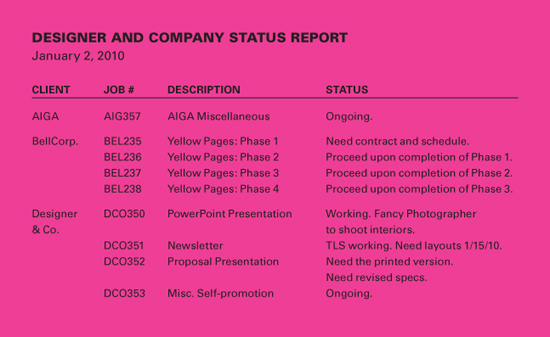

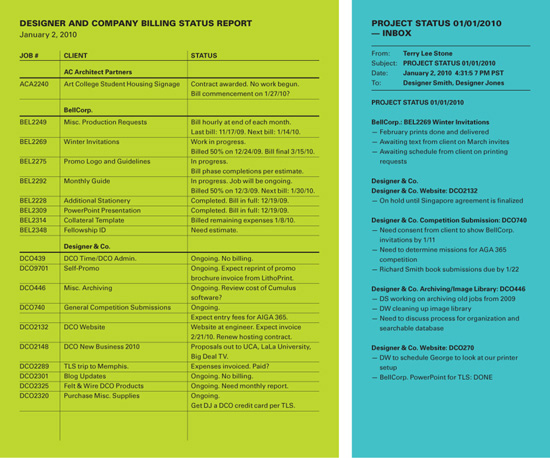

These charts illustrate three versions of a design firm’s status report. The top one is a simple job list with minimal information about the status of work. The bottom right version, which is emailed to the design team, acts as more of a to-do list with more detailed tasks broken down. The bottom left chart is a billing status report in which a project manager provides a bookkeeper with billing information. Any and all of these documents can be used effectively to keep work flowing through a design firm.

The Advantages of Time Sheets

Another essential tool that well-run design firms use is the time sheet, which records how designers spend their workday. By breaking the workday into fifteen-minute increments, recording the tasks done, and assigning this time to an open job number, designers provide managers with important information that affects the project, and the firm’s overall health and wealth.

Time sheets

• Tell designers how they spent their time

• Record actual work on jobs

• Help determine profitability

• Assist in accurate billing

• Give employers an understanding of the staff’s efficiency

• Allow employees to justify their salaries

• Alert project managers to time/budget issues on jobs

• Inform hiring decisions and capacity planning

• Provide a means of more accurate scoping and pricing on future projects

Persuasion and Project Management

Every design project requires a guide who will be responsible for making sure the design team delivers on the client’s expectations. This role passes through several phases, and requires different skills depending on the project’s status:

• Leader: commanding the respect of the client and design team

• Manager: actively participating in and guiding the process

• Monitor: overseeing and being accountable for the project’s status

• Mentor: advising, counseling, and maybe even training team members

• Enforcer: compelling compliance and ensuring that things happen as required

Another important aspect of setting up a design project is empowering the person acting as project manager. Typically, a project manager is not the team members’ actual “boss.” Even if the entire team agrees in theory, in practice, they aren’t always easy to manage. Powerful persuasion skills used right from the start, and then applied throughout the project lifecycle, is critically important for any project manager.

Because the project manager is a functional lead in terms of getting the work done, and is often speaking to the various stakeholders, including the client, on a near-daily basis, the project manager needs to persuade people to trust him or her.

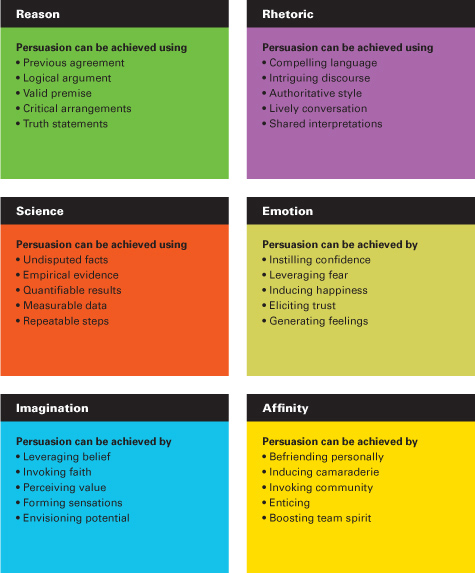

METHODS OF PERSUASION

This chart provides six methods of persuading people. You can use these concepts on your design team to manage projects, or with clients to manage the working relationship, particularly for getting approval on design solutions.

25 Tips for Design Project Managers

Salesmanship

One important aspect of persuasion in design is sales. Whether it’s receiving approval on a design solution or securing a deadline extension, getting your way may take a bit of selling. Of course, one element of salesmanship is all about showmanship: a dazzling and compelling performance. However, the best salesmanship in design occurs in the form of quiet persuasion, when the client doesn’t feel you are selling them something. Rather, your suggestions seem to be a logical, inevitable, and desirable outcome.

Any designer can learn from a great salesperson. Here are some things that effective salespeople do that might help a design manager:

• Have a clear objective.

• Do their homework.

• Have good timing.

• Stay in the moment.

• Use relevant triggers.

• Present persuasively.

• Listen and respond.

• Enjoy negotiating.

• Connect with others.

• Use visual aids.

• Aren’t afraid to use charm.

• Keep their eyes on the prize (the clear objective).

• Don’t take things personally.

• Know when to call it quits.

• Rise up and do it all over again.