CHAPTER 4

MORE THAN TINKERING AT THE MARGINS

We are told routinely that the first priority must be a strong economy. Yet, we know now that we should seek first a strong society, strong nature, and a strong democracy. Today’s economy offers little help in these regards. We must move beyond it. We need to reinvent the economy, not merely restore it.

JAMES GUSTAVE SPETH, FORMER ADMINISTRATOR, UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME

When economic failure is systemic, temporary fixes, even very expensive ones like the Wall Street bail-out, are like putting a bandage on a cancer. They may create a temporary sense of confidence, but the effect is solely cosmetic.

Unfortunately, even influential pundits who recognize the seriousness of the environmental and social dimensions of the current economic crisis generally limit their recommendations to a tune-up of the existing system. It is rare indeed to hear establishment voices call for a redesign of our economic institutions.

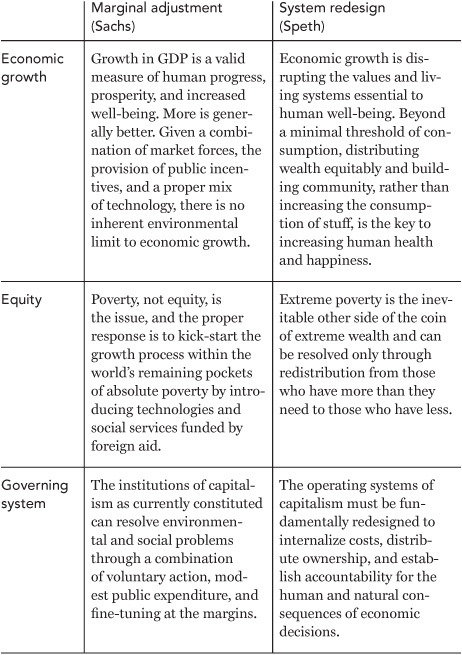

Jeffrey Sachs and James Gustave Speth are both influential establishment authors who in recent books present nearly identical statements of the need for action to reverse environmental damage and eliminate poverty. Their recommendations, however, are worlds apart. Sachs focuses on the symptoms and prescribes a bandage. Speth takes a holistic approach, looks upstream for the cause, and prescribes a cultural and institutional transformation.1

I contrast the perspectives of Sachs and Speth on three defining economic issues in Table 4.1. The differences are instructive, because we must learn to distinguish those who would lull us into believing we can get by with adjustments at the margins, à la Sachs, the neoclassical economist, from those who offer serious solutions based on a deep system redesign, à la Speth, the systems ecologist.

SACHS: PAINLESS FINE-TUNING

Jeffrey Sachs, an economist by training and perspective, is known for his work as an economic adviser to national governments and an array of public institutions. The New York Times once described him as “probably the most important economist in the world.”2

Sachs opens Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet(2008) with a powerful and unequivocal statement that raises expectations of a bold break from those he refers to as “free-market ideologues”:

The challenges of sustainable development — protecting the environment, stabilizing the world’s population, narrowing the gaps between rich and poor, and ending extreme poverty — will take center stage. Global cooperation will have to come to the fore. The very idea of competing nation-states that scramble for markets, power, and resources will become passé.…The pressures of scarce energy resources, growing environmental stresses, a rising global population, legal and illegal mass migration, shifting economic power, and vast inequalities of income are too great to be left to naked market forces and untrammeled geopolitical competition among nations.3

Table 4.1 Tinkering versus Transforming

That declaration would have served equally well as an opening statement for Speth, who agrees that government must play an essential role, and that nations must cooperate, in any effort to effect meaningful solutions. From there, however, we might wonder whether they live in different worlds.

The Tech Fix

Sachs assures us that we can end environmental stress and poverty with modest investments in existing technologies to sequester carbon, develop new energy sources, end population growth, make more efficient use of water and other natural resources, and jump-start economic growth in the world’s remaining pockets of persistent poverty. In a 2007 lecture to the Royal Society in London, Sachs made clear his belief that there is no need to redistribute wealth, cut back material consumption, or otherwise reorganize the economy:

I do not believe that the solution to this problem is a massive cutback of our consumption levels or our living standards. I think the solution is smarter living. I do believe that technology is absolutely critical, and I do not believe…that the essence of the problem is that we face a zero sum that must be redistributed. I’m going to argue that there’s a way for us to use the knowledge that we have, the technology that we have, to make broad progress in material conditions, to not require or ask the rich to take sharp cuts of living standards, but rather to live with smarter technologies that are sustainable, and thereby to find a way for the rest of the world, which yearns for it, and deserves it as far as I’m concerned, to raise their own material conditions as well. The costs are much less than people think.4

Far from calling for a restraint on consumption, Sachs projects global economic expansion from $60 trillion in 2005 to $420 trillion in 2050. Relying on what he calls a “back-of-the-envelope calculation,” he estimates that the world’s wealthy nations can eliminate extreme poverty and develop and apply the necessary technologies to address environmental needs with an expenditure of a mere 2.4 percent of the projected midcentury economic output. Problem painlessly solved, at least in Sachs’s mind.

Growth as Usual

Sachs gives no indication of why, if we can stabilize population and meet the needs of the poor with a modest expenditure, we should need or even want a global economy seven times as large as its present size. Like most other economists, and indeed the general public, Sachs simply assumes that economic growth is both good and necessary. It apparently never occurs to him to question this assumption, which Speth demonstrates to be false.

Furthermore, because Sachs maintains that the poorest of the poor can be put on the path to economic growth with no more than a very modest redistribution, he seems to assume that consumption will continue to increase across the board. He says nothing about what forms of consumption can continue to multiply without placing yet more pressure on already overstressed natural systems. Unless the already affluent are driving even bigger cars, living in bigger houses, eating higher on the food chain, traveling farther with more frequency, and buying more electronic gear, what exactly will they be consuming more of? From what materials will it be fabricated? What energy sources will be used? In what way will this increased consumption improve their quality of life? Sachs fails to consider such questions.

Nor does Sachs mention the realities of political power and resource control — for example, the reality that in most instances, poor countries are poor not because they receive too little foreign aid but because we of the rich nations have used our military and economic power to expropriate their resources to consume beyond our own means. It is troubling, although not surprising, that Sachs’s reassuring words get an attentive hearing among establishment power holders.

SPETH: REDIRECTION AND REDESIGN

James Gustave Speth, who has degrees in law and economics, has had a distinguished career as the founder and former head of the World Resources Institute, the administrator of the United Nations Development Programme, and dean of the Yale University School of Forestry. Speth writes from the perspective of a systems ecologist.

The End of Growth and Capitalism

In stark contrast to Sachs, Speth concludes in The Bridge at the Edge of the World: Capitalism, the Environment, and Crossing from Crisis to Sustainability (2008) that “the planet cannot sustain capitalism as we know it.” He recommends that “the operating system of capitalism” be redesigned to support the development of local economies populated with firms that feature worker and community ownership and that corporations be chartered only to serve the public interest.

Rather than settle for a simplistic back-of-the-envelope projection, Speth takes a hard look at the research on GDP growth and environmental damage. He notes that despite a slight decline in the amount of environmental damage per increment of growth, growth in GDP always increases environmental damage. The relationship is inherent in the simple fact that GDP is mostly a measure of growth in consumption, which is the driving cause of environmental decline. Speth is clear that even though choosing “green” products may be a positive step, not buying at all beats buying green almost every time:

To sum up, we live in a world where economic growth is generally seen as both beneficent and necessary — the more, the better; where past growth has brought us to a perilous state environmentally; where we are poised for unprecedented increments in growth; where this growth is proceeding with wildly wrong market signals, including prices that do not incorporate environmental costs or reflect the needs of future generations; where a failed politics has not meaningfully corrected the market’s obliviousness to environmental needs; where economies are routinely deploying technology that was created in an environmentally unaware era; where there is no hidden hand or inherent mechanism adequate to correct the destructive tendencies. So, right now, one can only conclude that growth is the enemy of environment. Economy and environment remain in collision.5

After examining the abuses of corporate power, Speth endorses the call to revoke the charters of corporations that grossly violate the public interest, and to exclude or expel unwanted corporations, roll back limited liability, eliminate corporate personhood, bar corporations from making political contributions, and limit corporate lobbying.

Health and Happiness

Speth is clear that we are unlikely as a species to implement the measures required to bring ourselves into balance with the environment so long as economic growth remains an overriding policy priority, consumerism defines our cultural values, and the excesses of corporate behavior are unconstrained by fairly enforced rules. To correct our misplaced priorities, he recommends replacing financial indicators of economic performance, such as GDP, with wholly new measures based on nonfinancial indicators of social and environmental health — the things we should be optimizing. Speth quotes psychologist David Myers, whose essay “What Is the Good Life?” claims that Americans have

big houses and broken homes, high incomes and low morale, secured rights and diminished civility. We were excelling at making a living but too often failing at making a life. We celebrated our prosperity but yearned for purpose. We cherished our freedoms but longed for connection. In an age of plenty, we were feeling spiritual hunger. These facts of life lead us to a startling conclusion: Our becoming better off materially has not made us better off psychologically.6

This is consistent with studies finding that beyond a basic threshold, equity and community are far more important determinants of health and happiness than income or possessions. Indeed, as Speth documents, economic growth tends to be associated with increases in individualism, social fragmentation, inequality, depression, and even impaired physical health.

Social Movements

Speth gives significant attention to social movements grounded in an awakening spiritual consciousness, which are creating communities of the future from the bottom up, practicing participatory democracy, and demanding changes in the rules of the game.

Many of our deepest thinkers and many of those most familiar with the scale of the challenges we face have concluded that the transitions required can be achieved only in the context of what I will call the rise of a new consciousness. For some, it is a spiritual awakening — a transformation of the human heart. For others it is a more intellectual process of coming to see the world anew and deeply embracing the emerging ethic of the environment and the old ethic of what it means to love thy neighbor as thyself.7

![]()

By this time, given the strength of the evidence to the contrary, it is difficult to take seriously anyone who assumes, without question, that the global economy can expand to seven times its current size between now and 2050 without collapsing Earth’s life support system. Unfortunately, Jeffrey Sachs demonstrates the intellectual myopia common to many professional economists whose ideological assumptions trump reality.

When we seek guidance on dealing with the complex issues relating to interactions between human economies and the planetary ecosystems in which they are embedded, we are best advised to turn to those like James Gustave Speth, who view the world through a larger and less ideologically clouded lens — and who, not incidentally, recognize the distinction between real wealth and phantom wealth.

It is instructive, however, that not even Speth addressed what has become the elephant in the middle of the room — one that had not yet moved to the forefront of the public consciousness at the time he and Sachs were writing their respective books. The elephant — an out-of-control and outof-touch financial system devoted to speculation, inflating financial bubbles, stripping corporate assets, and predatory lending — was dramatically exposed by the credit collapse. Though costly, the collapse thus has been something of a blessing. It has brought into sharp relief previously obscure but crucial system design choices relating to our financial institutions that we otherwise might not have recognized until they had done so much damage to the economy, our communities, and the environment that recovery would not be possible.